indians

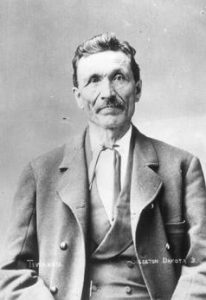

Little Wolf was a Cheyenne Indian who was often called “the greatest of the fighting Cheyenne.” Little Wolf was the chief of an elite Cheyenne military society called the Bowstring Soldiers. Little Wolf had demonstrated a rare form of bravery and a brilliant understanding of battle tactics from a very early age, which led to him becoming a trusted leader. His prowess showed first in conflicts with other Indians like the Kiowa, but even more in disputes with the United States Army, Little Wolf led or assisted in dozens of important Cheyenne victories.

Little Wolf was a Cheyenne Indian who was often called “the greatest of the fighting Cheyenne.” Little Wolf was the chief of an elite Cheyenne military society called the Bowstring Soldiers. Little Wolf had demonstrated a rare form of bravery and a brilliant understanding of battle tactics from a very early age, which led to him becoming a trusted leader. His prowess showed first in conflicts with other Indians like the Kiowa, but even more in disputes with the United States Army, Little Wolf led or assisted in dozens of important Cheyenne victories.

While it has not been confirmed, most historians agree that Little Wolf was probably involved in the disastrous Fetterman Massacre of 1866. In that battle, the Cheyenne lured the 80 American soldiers out of the fort in Wyoming, and wiped them out. Cheyenne attacks also forced the United States military to abandon Fort Phil Kearney along the Bozeman Trail, and Little Wolf is believed to have led the war party in torching of the fort. He was also a leading participant in the greatest of the Plains Indian victories, the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

Even with such an impressive list of victories to his credit, Little Wolf, like many of the other Plains Indian warriors, was finally forced to make peace with the White Man. After the horrendous loss at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the army launched a major offensive. In 1877, the government sent Little Wolf to a reservation in Indian Territory. Little Wolf was disgusted with the conditions and the lack of supplies the Indians were forced to endure. In 1878 Little Wolf made up His mind to leave the reservation. His plan was to head north for the old Cheyenne territory in Wyoming and Montana. Chief Dull Knife and 300 of his followers went with him.

Little Wolf and Dull Knife made it clear that their intentions were peaceful, but the settlers in the territory we’re afraid they would attack. So, once again, the government sent cavalry forces that assaulted the Indians. Little Wolf’s skillful defensive maneuvers kept Cheyenne casualties low. When the band neared Fort Robinson, Nebraska, Dull Knife and some of his followers stopped there, but Little Wolf and the rest of the Cheyenne continued to march north to Montana.

In the spring of 1879, while still traveling north, Little Wolf and his followers were overtaken by a cavalry force  under the leadership of Captain W.P. Clark, who happened to be an old friend of Little Wolf’s. The confrontation could have easily turned violent, but with his force of warriors diminished and his people tired, Little Wolf was reluctant to fight the more powerful American army. Clark’s civilized and gracious treatment of Little Wolf helped convince the chief that further resistance was pointless, and he agreed to surrender.

under the leadership of Captain W.P. Clark, who happened to be an old friend of Little Wolf’s. The confrontation could have easily turned violent, but with his force of warriors diminished and his people tired, Little Wolf was reluctant to fight the more powerful American army. Clark’s civilized and gracious treatment of Little Wolf helped convince the chief that further resistance was pointless, and he agreed to surrender.

After returning to the reservation, Little Wolf briefly served as a scout for General Nelson A. Miles. However, during this time he disgraced himself among his people by killing one of his tribesmen. The formerly celebrated Cheyenne warrior lived out the rest of his life on the reservation but had no official influence among his own people. After all of his honorable leadership and years of respect among his peers, Little Wolf was, in the end, taken down by his one dishonorable act. People always remember the things you do wrong, but the things you do right seem to fade quickly away.

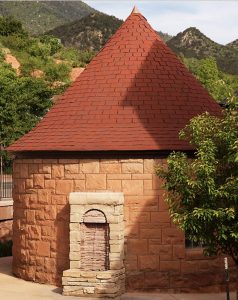

People of different, religions, races, and geological locations have been battling it out since time began. When the first white men came into the Western wilderness of America they found the tribes of Shoshone and Comanche Indians already at odds. It seems that their differences began at Manitou Springs. This “Saratoga of the West” is nestled in a hollow in the shadow of Pike’s Peak. It was in old days a common meeting ground for several families of Indians…possibly bringing about the fights over it. While there were fights over the area, councils were held in safety there, for no Indian dared provoke the wrath of the Manitou whose breath sparkled in the “medicine waters.”

People of different, religions, races, and geological locations have been battling it out since time began. When the first white men came into the Western wilderness of America they found the tribes of Shoshone and Comanche Indians already at odds. It seems that their differences began at Manitou Springs. This “Saratoga of the West” is nestled in a hollow in the shadow of Pike’s Peak. It was in old days a common meeting ground for several families of Indians…possibly bringing about the fights over it. While there were fights over the area, councils were held in safety there, for no Indian dared provoke the wrath of the Manitou whose breath sparkled in the “medicine waters.”

As the story goes, “centuries ago a Shoshone and a Comanche stopped at Manitou Springs on their return from a hunt to get a drink of water. The Shoshone had been successful, but the Comanche was empty-handed and ill-tempered, jealous of the other’s skill and fortune. Flinging down the fat deer that he was bearing homeward on his shoulders, the Shoshone bent over the spring of sweet water, and, after pouring a handful of it on the ground, as a libation (an act of pouring a liquid as a sacrifice) to the spirit of the place, he put his lips to the surface.”

The Comanche saw an opportunity to vent his anger. His quarrel began like this, “Why does a stranger drink

the water at the spring that his children may drink it undefiled. I am Ausaqua, chief of Shoshone, and I drink at the head-water. Shoshone and Comanche are brothers. Let them drink together. No. The Shoshone pays tribute to the Comanche, and Wacomish leads that nation to war. He is chief of the Shoshone as he is of his own people. Wacomish lies. His tongue is forked, like the snake’s. His heart is black. When the Great Spirit made his children he said not to one, ‘Drink here,’ and to another, ‘Drink there,’ but gave water that all might drink.”

the water at the spring that his children may drink it undefiled. I am Ausaqua, chief of Shoshone, and I drink at the head-water. Shoshone and Comanche are brothers. Let them drink together. No. The Shoshone pays tribute to the Comanche, and Wacomish leads that nation to war. He is chief of the Shoshone as he is of his own people. Wacomish lies. His tongue is forked, like the snake’s. His heart is black. When the Great Spirit made his children he said not to one, ‘Drink here,’ and to another, ‘Drink there,’ but gave water that all might drink.”

It is said, that the Shoshone didn’t answer, but as Ausaqua stooped toward the bubbling surface Wacomish crept behind him. He jumped on him and pushed his head under the water, holding it there until he drowned. It is said that as Wacomish “pulled the dead body from the spring the water became agitated, and from the bubbles arose a vapor that gradually assumed the form of a venerable Indian, with long white locks, in whom the murderer recognized Waukauga, father of the Shoshone and Comanche nation, and a man whose heroism and goodness made his name revered in both these tribes.” The face of the patriarch was dark with wrath, and he cried, in terrible tones, “Accursed of my race! This day thou hast severed the mightiest nation in the world. The blood of the brave Shoshone appeals for vengeance. May the water of thy tribe be rank and bitter in their throats.”

“Then, whirling up an elk-horn club, he brought it full on the head of the wretched man, who cringed before him. The murderer’s head was burst open and he tumbled lifelessly into the spring, that to this day is nauseous, while, to perpetuate the memory of Ausaqua, the Manitou smote a neighboring rock, and from it gushed a fountain of delicious water. The bodies were found, and the partisans of both the hunters began on that day a long and destructive warfare, in which other tribes became involved until mountaineers were arrayed against plainsmen through all that region.”

“Then, whirling up an elk-horn club, he brought it full on the head of the wretched man, who cringed before him. The murderer’s head was burst open and he tumbled lifelessly into the spring, that to this day is nauseous, while, to perpetuate the memory of Ausaqua, the Manitou smote a neighboring rock, and from it gushed a fountain of delicious water. The bodies were found, and the partisans of both the hunters began on that day a long and destructive warfare, in which other tribes became involved until mountaineers were arrayed against plainsmen through all that region.”

Of course, all this is folk lore, but the springs are real. They are Iron Spring, Twin Spring, Stratton Spring, Shoshone Spring, Wheeler Spring, Cheyenne, Soda and Navajo Springs, and Seven Minute Spring.

Deadwood, South Dakota maybe started out as an illegal town, but once it was established, there came a need for things like mail, supplies, and transportation, the latter of which brought the need for a stagecoach. The biggest problem with the stagecoach was the fact that the lawless element in the area thought it would be an easy target for robbery. The stagecoaches became a ride for the very brave. Soon it became apparent that the stagecoaches were going to need some protection.

Deadwood, South Dakota maybe started out as an illegal town, but once it was established, there came a need for things like mail, supplies, and transportation, the latter of which brought the need for a stagecoach. The biggest problem with the stagecoach was the fact that the lawless element in the area thought it would be an easy target for robbery. The stagecoaches became a ride for the very brave. Soon it became apparent that the stagecoaches were going to need some protection.

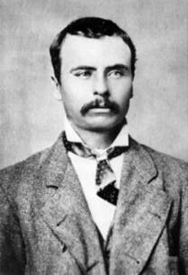

Daniel “Boone” May was born in Missouri in 1852. Going by the name of “Boone,” he was the son of Samuel and Nancy May, the seventh of nine children. Later, he moved with his family to Bourbon County, Kansas, where his father worked as a farmer. In 1876, “Boone” and his older brother moved to Cheyenne, Wyoming, where they worked in the freight business. During this time, the Black Hills were crawling with road agents and hostile Sioux Indians.It was a dangerous time to be working along the roadways in that area. Nevertheless, May did very well there, and he decided to buy a ranch between the Platte River and Deadwood by the end of that year.

“Boone’s” bravery and work ethic soon came to the attention of the stagecoach service, and he was soon recruited as a shotgun messenger for the Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage & Express Company. He also served as the station keeper at Robbers’ Roost in Wyoming Territory. Within just a few years, “Boone” was thought to have been in at least eight shooting incidents with outlaws. Many people said that he was the fastest gun in the Dakotas. His adventures soon became well known.

One of the first hold-ups “Boone” was involved in was in August, 1877, when a Deadwood Coach was intercepted at Robber’s Roost. On this occasion, even though “Boone” wanted to fight it out, he decided to lay down his weapons, because a woman and child were in the coach. The robbers made away with the passenger’s money, weapons and personal property. While they lost their things, I’m sure they decided that it was best to walk away with their lives. A short time later, “Boone” ran into one of the bandits, a man named Prescott Webb, in Deadwood and within no time, gunfire erupted between the two men. Though “Boone” was hit in the left wrist, he returned fire as Webb jumped on a horse to make his getaway. “Boone’s” shots hit Webb in the shoulder, and the horse several times, bringing it down. Webb was quickly arrested by Sheriff Seth Bullock and later that day, Webb’s companions who had aided in the robbery, were also arrested.

In 1878, stagecoaches known as “treasure coaches” were running regularly between Deadwood and Cheyenne. Their cargo was strong boxes filled with gold, as well as the U.S. Mail. These “treasure coach” stages often became the target of bandits, and after one of these coaches was held up on July 2, 1878, the U.S. Postal Service appointed a number of special agents to bring the outlaws to justice. “Boone” and ten other men were soon appointed as U.S. Deputy Marshals and equipped with good horses and ammunition. One of “Boone’s” first encounters with bandits as a U.S. Deputy Marshal occurred on the night of September 13, 1878. He and another messenger were trailing a Cheyenne bound coach which was approached by bandits near Old Woman’s Creek in the Wyoming Territory. “Boone” and another deputy, Zimmerman surprised the outlaws and shooting erupted. “Boone” wounded one bandit named Frank Towle and the others fled empty handed. Leaving their Towle wounded on the ground, the two messengers went after the other bandits but were unable to capture them. When they returned to the robbery site, Towle was gone.

On September 26, 1878, when “Boone” and other messengers were waiting to escort a coach at Beaver Station on the Wyoming-Dakota border, but the stage failed to show up. They went in search of the coach, and met another messenger who told them it had been robbed and a passenger killed. “Boone” quickly joined a posse to go after the outlaws, but they escaped. The following month, “Boone” learned of the hiding place of a robber named Archie McLaughlin and quickly went after him and his gang. Capturing them north of Cheyenne, the outlaws were sent under guard to Deadwood on the northbound coach. Unfortunately, the stage never make it, because on November 3, 1878, it was stopped by vigilantes who hanged Archie McLaughlin and another man named Billy Mansfield. The next month, “Boone” was in a posse that brought in a robber named Tom Price. The bandit tried to escape, and was wounded, and then was brought in. Late in 1879, “Boone” was sent to assist Special Agent William Llewellyn in the capture of a mail robber named Curley Grimes. They tracked the outlaw  to Elk Creek, located halfway between Rapid City and Fort Meade where they arrested him. That night, as the group neared Fort Meade, Grimes attempted to escape and was shot and killed by “Boone” and Llewellyn. By this time, “Boone” had made such a reputation for himself that he became a target for many of the outlaws who repeatedly tried to assassinate him, unsuccessfully. “Boone” also worked as a messenger for the Black Hills Placer Mining Company in the summer of 1880, and was said to have killed at least one robbers during this time. A short time later, “Boone” resigned from the company and left the Black Hills. He turned up in Santiago, Chili in 1883. He shot an army officer in 1891, he fled to Brazil. He died of yellow fever in Rio de Janeiro in 1910.

to Elk Creek, located halfway between Rapid City and Fort Meade where they arrested him. That night, as the group neared Fort Meade, Grimes attempted to escape and was shot and killed by “Boone” and Llewellyn. By this time, “Boone” had made such a reputation for himself that he became a target for many of the outlaws who repeatedly tried to assassinate him, unsuccessfully. “Boone” also worked as a messenger for the Black Hills Placer Mining Company in the summer of 1880, and was said to have killed at least one robbers during this time. A short time later, “Boone” resigned from the company and left the Black Hills. He turned up in Santiago, Chili in 1883. He shot an army officer in 1891, he fled to Brazil. He died of yellow fever in Rio de Janeiro in 1910.

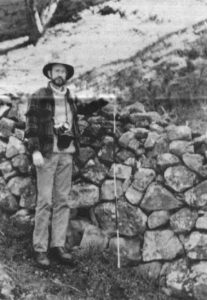

There is a wall that lots o people might have known about, or maybe few people know about, but while I’m sure I’ve seen parts of it in movies, I didn’t really know about it. The series of walls, known as the East Bay Walls or the Berkeley Mystery Walls. Of course that doesn’t really apply to one area, because the reality is that there are many of the crude walls throughout the hills surrounding the San Francisco Bay area. In some place the walls are as much as 3 feet tall, and 3 feet wide. The walls are very old and they were built without mortar. The walls run in sections, and they can be a few feet to over a mile long. Even more odd, is the fact that the rocks are a variety of sizes ranging from basketball-sized rocks, to large sandstone boulders weighing a ton or more. Parts of the walls seem to be just piles of rocks, but in other places it appears the walls were carefully constructed. No one knows the exact age of the walls, but they have an old appearance. Many of the formations have sunk far into the earth, and are often completely overgrown with different plants. The walls are not continuous, so they are not fences. They are not tall enough to have been used as defensive walls. The East Bay Regional Park District simply calls them “rock walls” and insists that they are not mysterious. Livestock, such as cattle, have grazed in the east and south Bay Area hills since the arrival of European

There is a wall that lots o people might have known about, or maybe few people know about, but while I’m sure I’ve seen parts of it in movies, I didn’t really know about it. The series of walls, known as the East Bay Walls or the Berkeley Mystery Walls. Of course that doesn’t really apply to one area, because the reality is that there are many of the crude walls throughout the hills surrounding the San Francisco Bay area. In some place the walls are as much as 3 feet tall, and 3 feet wide. The walls are very old and they were built without mortar. The walls run in sections, and they can be a few feet to over a mile long. Even more odd, is the fact that the rocks are a variety of sizes ranging from basketball-sized rocks, to large sandstone boulders weighing a ton or more. Parts of the walls seem to be just piles of rocks, but in other places it appears the walls were carefully constructed. No one knows the exact age of the walls, but they have an old appearance. Many of the formations have sunk far into the earth, and are often completely overgrown with different plants. The walls are not continuous, so they are not fences. They are not tall enough to have been used as defensive walls. The East Bay Regional Park District simply calls them “rock walls” and insists that they are not mysterious. Livestock, such as cattle, have grazed in the east and south Bay Area hills since the arrival of European  settlers. Clearing land of scattered rocks would have eased the ability to move livestock. Placing the rocks into walls would have helped to guide the movement of the animals or to help corral them. That makes sense, but some of those rocks were very heavy. So how did they do that.

settlers. Clearing land of scattered rocks would have eased the ability to move livestock. Placing the rocks into walls would have helped to guide the movement of the animals or to help corral them. That makes sense, but some of those rocks were very heavy. So how did they do that.

There is no written documentation to identify when they were built, by whom, or why. So, some people consider them mysterious. It has been suggested that the Ohlone Indians might have been the builders, but in reality, they were hunter-gatherers, and didn’t build permanent structures. Some specialists have mentioned that the walls look similar to structures found in rural Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maine, but they are different in that those walls were built around farms by the early setters, and these don’t have the same kinds of layouts. In 1904, UC-Berkeley Professor John Fryer suggested that the walls were made by Mongolian Chinese who traveled to California before the Europeans. Unfortunately, there is little evidence for this or for pre-Columbian Chinese influence in America. Forensic geologist Scott Wolter has theorized that the wall is only two to three hundred years old, suggested by the thick weathering rind on the limestone rock he was authorized to sample. Recent testing of lichen on the rocks suggests that they were probably built between 1850 and 1880, the early American era in California. Settlers might have built the walls using Chinese, Mexican, or Native American laborers, although specifically who built them has not been determined.

One of the many old stone walls that appear around the San Francisco Bay area is in the foothills of eastern  Santa Clara County. The stone walls are accessible in several area parks, including Ed R. Levin County Park in Santa Clara County and Mission Peak Regional Preserve in Alameda County, as well as many other parks. As of 2016, archaeologist Jeffrey Fentress has been measuring and mapping the walls, hoping to eventually gain protection from development or other destruction. Additional stone walls with unclear origin or purpose occur in other places near the San Francisco Bay, and researchers continue to discover more information about the walls. Whether these walls had a purpose at one time or not, they are certainly strange to those who try to look into them these days.

Santa Clara County. The stone walls are accessible in several area parks, including Ed R. Levin County Park in Santa Clara County and Mission Peak Regional Preserve in Alameda County, as well as many other parks. As of 2016, archaeologist Jeffrey Fentress has been measuring and mapping the walls, hoping to eventually gain protection from development or other destruction. Additional stone walls with unclear origin or purpose occur in other places near the San Francisco Bay, and researchers continue to discover more information about the walls. Whether these walls had a purpose at one time or not, they are certainly strange to those who try to look into them these days.

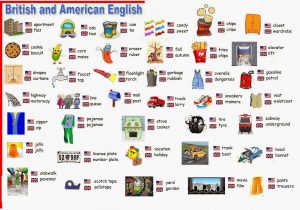

When the colonists left England to form America, they were like the younger sibling, at least when it came to language and much of how they ran the country. Nevertheless, like that younger sibling, things began to change pretty quickly. Part of the change was due simply to distance. When you don’t hear a language all the time, you begin to vary in your own speech. I didn’t really realize there was such a difference between American English and British English, other than the accent of course. Still, I noticed that more and more forms were asking which of the two I spoke. I always thought that it was an odd question, because English is English…right? Well, the correct answer is…wrong!! And when I thought about it, I knew that to be true.

When the colonists left England to form America, they were like the younger sibling, at least when it came to language and much of how they ran the country. Nevertheless, like that younger sibling, things began to change pretty quickly. Part of the change was due simply to distance. When you don’t hear a language all the time, you begin to vary in your own speech. I didn’t really realize there was such a difference between American English and British English, other than the accent of course. Still, I noticed that more and more forms were asking which of the two I spoke. I always thought that it was an odd question, because English is English…right? Well, the correct answer is…wrong!! And when I thought about it, I knew that to be true.

The changes began almost immediately after the first Englishman set foot on American soil. It all started with “Americanisms.” These “Americanisms” have been created or changed from other English terms to produce a language that differs from our forefathers, signifying our uniqueness and independence. I’m sure our founders were rather pleased with themselves with this process, if they realized it at all. By the time of the first United States census, in 1790, there were four million Americans, 90% of whom were descendants of English colonists. When I think of the speed of that growth, it strikes me as phenomenal to say the least. Because of the large English background, there was no question that our official native language would be “English,” but it would not be the same as that spoken in Great Britain. “Americanism” means a word or expression that originated in the United States. The term includes outright coinages and foreign borrowings which first became “English” in the United States, as well as older terms used in new senses first given them in American usage.

In fact, by 1720, the colonists knew that we did not speak the same language as the people in England. The most obvious reason was, of course, the sheer distance from England. Nevertheless, that was not the only  reason. Over the years, many words were borrowed from the Native Americans, as well as other immigrants from France, Germany, Spain, and other countries. We had to communicate with the people around us too, and other words that became obsolete “across the pond,” continued to be utilized in the colonies. In other cases, words simply had to be created in order to explain the unfamiliar landscape, weather, animals, plants, and living conditions that these early pioneers encountered. These things might not have existed in England.

reason. Over the years, many words were borrowed from the Native Americans, as well as other immigrants from France, Germany, Spain, and other countries. We had to communicate with the people around us too, and other words that became obsolete “across the pond,” continued to be utilized in the colonies. In other cases, words simply had to be created in order to explain the unfamiliar landscape, weather, animals, plants, and living conditions that these early pioneers encountered. These things might not have existed in England.

By 1756, the English would make the first “official” reference to the “American dialect.” Samuel Johnson made note of it a year after he published his Dictionary of the English Language. Johnson’s use of the term “American dialect” was not meant to simply explain the differences, but rather, was intended as an insult. It was rather like calling our language the “low class” version of the English language. Remember if you will, that there were those who did not think the United States should ever be a sovereign nation. Years earlier…as early as 1735, the English were calling our language “barbarous,” and referred to our “Americanisms” as barbarisms. The English sneered at our language, something that continued for more than a century after the Revolutionary War, as they laughed and condemned as unnecessary, hundreds of American terms and phrases.

Our newly independent Americans, were proud of their “new” American language, wearing it, as a badge of independence. In 1789, Noah Webster wrote in his Dissertations on the English Language: “The reasons for American English being different than English English are simple: As an independent nation, our honor requires us to have a system of our own, in language as well as government.” Our leaders, including Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Rush, agreed. It was not only good politics, it was sensible. The feelings of the “rest of the world” didn’t matter. The language changed even more during the western movement as Native American and  Spanish words became a part of our language.

Spanish words became a part of our language.

In 1923, the State of Illinois General Assembly, passed the act stating in part: “The official language of the State of Illinois shall be known hereafter as the “American” language and not as the “English” language.” A similar bill was also introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives the same year but died in committee. Now, after centuries of forming our “own” language, the English and American versions are once again beginning to blend as movies, songs, electronics, and global traveling bring the two “languages” closer together once again.

The other day, while reading an article about notable Native Americans, I came across a name that was familiar to me, but really didn’t seem like a Native American name. The name was Renville, the same name as my grand-nephew, James Renville. Immediately, I wondered if there might be a connection between Chief Gabriel Renville and my grand-nephew. The search didn’t take very long, before I had my answer. Gabriel Renville is my grand-nephew, James’ 1st cousin 7 times removed. I find that to be extremely amazing to think that James is related to an Indian chief. With that information, I wanted to fine out more abut this man.

The other day, while reading an article about notable Native Americans, I came across a name that was familiar to me, but really didn’t seem like a Native American name. The name was Renville, the same name as my grand-nephew, James Renville. Immediately, I wondered if there might be a connection between Chief Gabriel Renville and my grand-nephew. The search didn’t take very long, before I had my answer. Gabriel Renville is my grand-nephew, James’ 1st cousin 7 times removed. I find that to be extremely amazing to think that James is related to an Indian chief. With that information, I wanted to fine out more abut this man.

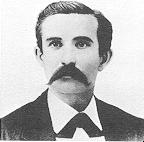

Chief Gabriel Renville was a mixed-blood Santee Sioux—his father was half French and his mother half-Scottish. He was born in April of 1825 at Big Stone Lake, South Dakota. Renville was the treaty chief of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Santee tribes and signed the 1867 treaty, which established the boundaries of the Lake Traverse Reservation. One source called him a Champion of Excellence.

He was careful to protect his people as much as he could, and was also instrumental in saving the lives of many white captives. During the 1862 Uprising, Renville opposed Little Crow and was influential in keeping many of the Santee out of the war. He lost a large amount of property, including horses appropriated by the hostile savages, or destroyed in consequence of his position to their murderous course. Renville served as chief of scouts for General Sibley during the campaign against the Sioux in 1863.

Even though Chief Renville was an ally of the whites, it didn’t help him when he settled on the reservation. The government agent there, Moses N. Adams, considered him hostile. Renville was the leader of the “scout party” which was in conflict with the “good church” Indians. I’m sure that was common in those days. Renville preserved many of the traditional Santee customs of polygamy and dancing, and he ignored Christianity, but he  was not opposed to economic progress and he and his followers became successful farmers on the reservation. However, the Sisseton agent favored the “church” Indians.

was not opposed to economic progress and he and his followers became successful farmers on the reservation. However, the Sisseton agent favored the “church” Indians.

Renville and other leaders of the traditional Indians accused Adams of discriminating against them in the disposition of supplies and equipment. He said Adams favored the idle church-goers instead of encouraging them to work….a situation not unlike the current welfare system. Agent Adams considered Renville a detriment and removed the chief form the reservation executive board which Adams had organized to carry out his policies. It was a move that was considered extreme. In 1874 Renville was finally successful in securing a government investigation of the Adam’s activities. The outcome of the investigation was an official censure of Adams. Chief Renville continued to practice the old Santee customs, yet he encouraged the Indians to farm. This progressive influence was greatly missed after his death in August 1892.

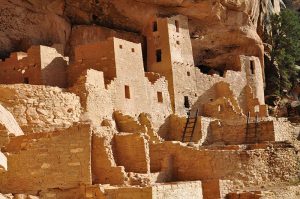

Most often, when we think of the early Americans, and their settlements, we think about the settlers who came over from Europe, but there were, of course, the many Indian tribes that existed here first. I’m not going to dispute whether the Indians or the White Man have more right to be here, because I truly believe that we should all be able to co-exist here after all these years, and that while treaties were broken many times, we have more than likely paid for this land a number of times, given the money that has been, and continues to be paid to the Native Americans. The oldest known culture in the United States was the Pueblo Indians, who lived in the Southwestern United States. Their name is Spanish for “stone masonry village dweller.” They are believed to be the descendants of three major cultures…the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Ancient Puebloans (Anasazi) Indians. I’m not sure how they would have come to be here, unless their ancestors were here first, but that is how the historians see it.

Most often, when we think of the early Americans, and their settlements, we think about the settlers who came over from Europe, but there were, of course, the many Indian tribes that existed here first. I’m not going to dispute whether the Indians or the White Man have more right to be here, because I truly believe that we should all be able to co-exist here after all these years, and that while treaties were broken many times, we have more than likely paid for this land a number of times, given the money that has been, and continues to be paid to the Native Americans. The oldest known culture in the United States was the Pueblo Indians, who lived in the Southwestern United States. Their name is Spanish for “stone masonry village dweller.” They are believed to be the descendants of three major cultures…the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Ancient Puebloans (Anasazi) Indians. I’m not sure how they would have come to be here, unless their ancestors were here first, but that is how the historians see it.

Over the years, the Ancient Puebloans, who had been a nomadic, hunter-gathering society, evolved into a sedentary culture. They made their homes in the Four Corners region of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Arizona. The Puebloans continued to hunt, but they also expanded to agriculture. They grew maze, corn, squash, and beans. They also raised turkeys and even developed a fairly complex irrigation system. They took up basket weaving and pottery, and became quite skilled in both. About this time, they began building the  buildings we think about when we think of the Pueblo Indians…villages, often on top of high mesas or in hollowed-out natural caves at the base of canyons. These multiple-room dwellings and apartment like complexes, designed with stone or adobe masonry, were the forerunner of the later pueblos.

buildings we think about when we think of the Pueblo Indians…villages, often on top of high mesas or in hollowed-out natural caves at the base of canyons. These multiple-room dwellings and apartment like complexes, designed with stone or adobe masonry, were the forerunner of the later pueblos.

Sadly, even with their successful life changes, the Ancient Puebloans way of life declined in the 1300’s, probably due to drought and inter-tribal warfare. They migrated south, primarily into New Mexico and Arizona, becoming what is today known as the Pueblo people. For hundreds of years, these Pueblo descendants lived a similar lifestyle to their ancestors. They continued to survive by hunting and farming, and also building “new” apartment-like structures, sometimes several stories high. These new structures were made of cut sandstone faced with adobe, which is a combination of earth mixed with straw and water. Sometimes, the adobe was poured into forms or made into sun-dried bricks to build walls that are often several feet thick. The buildings had flat roofs, which served as working or resting places, as well as observation points to watch for approaching enemies and view ceremonial occasions. For better defense, the outer walls generally had no doors or windows, but instead, window openings in the roofs, with ladders leading into the interior.

Each family unit consisted of a single room of the building unless the family grew too large. Then side-rooms were sometimes added. The houses of the pueblo were usually built around a central, open space or plaza in the middle of which was a “kiva,” a sunken chamber used for religious purposes. Each pueblo was an independent and separate community. The different pueblos shared similarities in language and customs, but each pueblo had its own chief, and sometimes two chiefs, a summer and winter chief, who alternated. Most important affairs, such was war, hunting, religion, and agriculture, however, were governed by priesthoods or secret societies. Each pueblo was almost a separate country.

Each family unit consisted of a single room of the building unless the family grew too large. Then side-rooms were sometimes added. The houses of the pueblo were usually built around a central, open space or plaza in the middle of which was a “kiva,” a sunken chamber used for religious purposes. Each pueblo was an independent and separate community. The different pueblos shared similarities in language and customs, but each pueblo had its own chief, and sometimes two chiefs, a summer and winter chief, who alternated. Most important affairs, such was war, hunting, religion, and agriculture, however, were governed by priesthoods or secret societies. Each pueblo was almost a separate country.

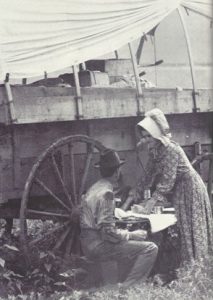

When we think of the Old West, the Pioneer movement, the Gold Rush, and generally, the settling of the United States, our minds immediately go to the brave men who fought the Indians, ran the wagon trains, weathered the harsh winters looking for their fortunes, and fought in the wars to make this a free nation, but seldom do we think of the anonymous heroes of that time…the women. There is a saying, “Behind every great man there’s a great woman.” that saying is one reference to the many women who have set aside their own comforts to support their man in the goals and dreams he has. In many ways that saying is the picture of the Pioneer woman, but it actually leaves something out. Just because her man did not become famous, doesn’t mean that the woman was any less behind him, supporting him in all he did.

When we think of the Old West, the Pioneer movement, the Gold Rush, and generally, the settling of the United States, our minds immediately go to the brave men who fought the Indians, ran the wagon trains, weathered the harsh winters looking for their fortunes, and fought in the wars to make this a free nation, but seldom do we think of the anonymous heroes of that time…the women. There is a saying, “Behind every great man there’s a great woman.” that saying is one reference to the many women who have set aside their own comforts to support their man in the goals and dreams he has. In many ways that saying is the picture of the Pioneer woman, but it actually leaves something out. Just because her man did not become famous, doesn’t mean that the woman was any less behind him, supporting him in all he did.

Pioneer women were there, on the home front, working hard all day trying to keep their house clean in a rugged windswept frontier. Her floors were often made of dirt, and yet she swept them. The water came from a well, or a nearby creek, and she had to haul it into the house, because her man was off hunting to bring in food for the family. The house was crudely constructed with logs and often had a sod roof, and she was right there working like a man beside her husband to get that house built. She watched over the children, and kept them safe from the many perils that were a daily encounter. From snakes, to bears, to mountain lions, to Indians, she did what she needed to, even to the point of handling a gun as well as her husband did. And yet, history looked at her as the weaker part of the partnership, the one who needed to be sheltered and protected. History looked at her as if she could not  even bear to hear about certain things, because they might be too upsetting to her. In reality, they had vastly underestimated their women.

even bear to hear about certain things, because they might be too upsetting to her. In reality, they had vastly underestimated their women.

When the men got hurt, and the garden needed to be cared for, the women would till the ground…fighting with the tiller behind a horse, and winning the battle. These women took care of the house, the children, the sick or injured husband, and the garden or other crops, all without batting an eye. These women knew all about the hardships of frontier living, and when the going got tough, they didn’t turn and run back east. When the Indians attacked, they stayed and fought with their men. They could not afford to hide in a cellar, their hands were needed to hold a gun. They even faced the Indians alone, when their men were away, becoming excellent negotiators, who were able to make a trade of their wares that, in the end saved their own lives and the lives of their families. They were determined to make this new frontier work, and for the most part, they did it all without making a name for themselves. Sometimes, when we look up ancestors in historic archives, these women are either listed only as Mrs, acknowledging only the husband’s name, or they were listed only as the wife of their husband. Their true identity sometimes remains forever a mystery, and yet, they were heroes…but, they were anonymous heroes. The great men they stood behind, thereby making these men successful, may have been heroes of the frontier, and their name may have been one that every history book told us all about,  but their wives, who worked quietly beside them, remained unknown. We knew about the exploits of the men, the towns they founded, the travels they made exploring ever westward, but the women who were there with them, cooking the meals while the men talked, cleaning up afterward alone, delivering their babies often with only the help of their husband, carrying a baby, while weeding a garden, and feeding their family before themselves, going hungry, if necessary, to make sure the family was taken care of…these women rarely made the history books. Their job must have seemed to mundane to be considered adventurous, but without their contribution, this nation would not have become the great Republic that it is.

but their wives, who worked quietly beside them, remained unknown. We knew about the exploits of the men, the towns they founded, the travels they made exploring ever westward, but the women who were there with them, cooking the meals while the men talked, cleaning up afterward alone, delivering their babies often with only the help of their husband, carrying a baby, while weeding a garden, and feeding their family before themselves, going hungry, if necessary, to make sure the family was taken care of…these women rarely made the history books. Their job must have seemed to mundane to be considered adventurous, but without their contribution, this nation would not have become the great Republic that it is.

Most people have heard of Crazy Horse, the Lakota Sioux Indian who has been memorialized in the Black Hills. Most of us know that Crazy Horse was a great warrior, but I did not know much about his upbringing. Crazy Horse was born on the Republican River about 1845. Crazy Horse was an uncommonly handsome man, and a man of refinement and grace. He was as modest and courteous as Chief Joseph, but unlike Chief Joseph, Crazy Horse was a born warrior, but a gentle warrior, a true brave, who stood for the highest ideal of the Lakota Sioux people. Of course, you would never hear these things from his enemies, but history should probably judge him more by the accounts of those who knew him…his own people.

Most people have heard of Crazy Horse, the Lakota Sioux Indian who has been memorialized in the Black Hills. Most of us know that Crazy Horse was a great warrior, but I did not know much about his upbringing. Crazy Horse was born on the Republican River about 1845. Crazy Horse was an uncommonly handsome man, and a man of refinement and grace. He was as modest and courteous as Chief Joseph, but unlike Chief Joseph, Crazy Horse was a born warrior, but a gentle warrior, a true brave, who stood for the highest ideal of the Lakota Sioux people. Of course, you would never hear these things from his enemies, but history should probably judge him more by the accounts of those who knew him…his own people.

No matter what Crazy Horse the man was or was thought to be, Crazy Horse, the boy showed great bravery a number of times. In those days, the Sioux prided themselves on the training and development of their sons and daughters, and not a step in that development was overlooked as an excuse to bring the child before the public by giving a feast in its honor. At such times the parents often gave so generously to the needy that they almost impoverished themselves, thus setting an example to the child of self-denial for the general good. His first step alone, the first word spoken, first game killed, the attainment of manhood or womanhood, each was the occasion of a feast and dance in his honor, at which the poor always benefited to the full extent of the parents’ ability. He was carefully brought up according to the tribal customs. I suppose it would have put him in the Indian version of today’s high society.

He was about five years old when the tribe was snowed in one severe winter. They were very short of food, but his father tirelessly hunted for food. The buffalo, their main dependence, were not to be found, but he was out in the storm and cold every day and finally brought in two antelopes. Young Crazy Horse got on his pet pony and rode through the camp, telling the old folks to come to his mother’s teepee for meat. Neither his father nor mother had authorized him to do this, and before they knew it, old men and women were lined up before the teepee home, to receive the meat, in answer to his invitation. As a result, the mother had to distribute nearly all of it, keeping only enough for two meals. On the following day he asked for food. His mother told him that the old folks had taken it all, and added: “Remember, my son, they went home singing praises in your name, not my name or your father’s. You must be brave. You must live up to your reputation.” And so he did.

When he was about twelve he went to look for the ponies with his little brother, whom he loved much, and took a great deal of pains to teach what he had already learned. They came to some wild cherry trees full of ripe fruit. Suddenly, the brothers were startled by the growl and sudden rush of a bear. Young Crazy Horse pushed his brother up into the nearest tree and then jumped upon the back of one of the horses, which was frightened and ran some distance before he could control him. As soon as he could, he turned him about and came back, yelling and swinging his lariat over his head. The bear at first showed fight but finally turned and ran. The old man who told me this story added that young as he was, he had some power, so that even a grizzly did not care to tackle him. I believe it is a fact that a grizzly will dare anything except a bell or a lasso line, so he accidentally hit upon the very thing which would drive him off.

At this period of his life, as was customary with the best young men, he spent much time in prayer and solitude. Just what happened in these days of his fasting in the wilderness and upon the crown of bald buttes, no one will ever know. These things may only be known when one has lived through the battles of life to an honored old age. He was much sought after by his youthful associates, but was noticeably reserved and modest. Yet, in the moment of danger he at once rose above them all…a natural leader! Crazy Horse was a typical Sioux brave, and from the point of view of the white man, an ideal hero.

At the age of sixteen he joined a war party against the Gros Ventres. He was well in the front of the charge,  and at once established his bravery by following closely one of the foremost Sioux warriors, by the name of Hump, drawing the enemy’s fire and circling around their advance guard. Suddenly Hump’s horse was shot from under him, and there was a rush of warriors to kill or capture him while he was down. Amidst a shower of arrows Crazy Horse jumped from his pony, helped his friend into his own saddle, sprang up behind him, and carried him off to safety, although they were hotly pursued by the enemy. Thus, in his first battle he associated himself with the wizard of Indian warfare, and Hump, who was then at the height of his own career. Hump pronounced Crazy Horse the coming warrior of the Teton Sioux. He was killed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in 1877, so that he lived barely thirty-three years.

and at once established his bravery by following closely one of the foremost Sioux warriors, by the name of Hump, drawing the enemy’s fire and circling around their advance guard. Suddenly Hump’s horse was shot from under him, and there was a rush of warriors to kill or capture him while he was down. Amidst a shower of arrows Crazy Horse jumped from his pony, helped his friend into his own saddle, sprang up behind him, and carried him off to safety, although they were hotly pursued by the enemy. Thus, in his first battle he associated himself with the wizard of Indian warfare, and Hump, who was then at the height of his own career. Hump pronounced Crazy Horse the coming warrior of the Teton Sioux. He was killed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in 1877, so that he lived barely thirty-three years.

For many years I was essentially unaware of the Texas Rangers. Then, with the show Walker, Texas Ranger, this elite group of law enforcement officers became a household word. Of course, the Texas Rangers have been an institution in Texan since they were unofficially created by Stephen F. Austin in a call-to-arms written in 1823. They were first headed by Captain Morris. After a decade, on August 10, 1835, Daniel Parker introduced a resolution to the Permanent Council creating a body of rangers to protect the border, something we continue to need today.

For many years I was essentially unaware of the Texas Rangers. Then, with the show Walker, Texas Ranger, this elite group of law enforcement officers became a household word. Of course, the Texas Rangers have been an institution in Texan since they were unofficially created by Stephen F. Austin in a call-to-arms written in 1823. They were first headed by Captain Morris. After a decade, on August 10, 1835, Daniel Parker introduced a resolution to the Permanent Council creating a body of rangers to protect the border, something we continue to need today.

On May 2, 1874, John B. Jones began his adventurous career as a lawman, when he was appointed as a major in the Texas Rangers. Jones was born in Fairfield District, South Carolina, in 1834. He moved to Texas with his father when he was a small boy. He went to college at Mount Zion College in South Carolina, and after graduating he returned to his home in Texas to enlist in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Talented and ambitious, he eventually rose to the rank of adjutant general. Jones took the defeat of the Confederacy hard, and after the war, he spent some time traveling in Mexico and Brazil trying to establish a colony for other disgruntled former Confederates. After determining that the colonial schemes held little promise for success, he returned to Texas where his military experience won him his major’s commission with the Texas Rangers.

Jones commanded the Frontier Battalion, a force of about 500 men stationed along the Texas frontier from the Red River to the Rio Grande. His mission was two-fold: to keep hostile-border Indians out of Texas and control the outlaws within Texas. His first Indian fight came less than six weeks later. While patrolling near Jacksboro, Texas, with 28 men, Jones spotted a band of more than 100 Indians that he thought were hostile Kiowa, Commanche, and Apache. Displaying more courage than wisdom, Jones directed his small band to attack the larger force of Indians. In the ensuing battle, two of the Rangers were killed and two wounded, but they were lucky to escape without more serious losses. Jones, feeling quite chastened, acted with greater care in his subsequent battles with Indians. Soon, his force became highly effective in repulsing invasions.

Four years later, Jones took on one of the most notorious outlaws on the Texas frontier…a man named Sam Bass. For some months, Bass and his gang had been staging train robberies in Texas. Although most of the robberies failed to net much money because Bass and his partners were incompetent amateurs. Nevertheless, the people of Texas demanded that Bass be stopped. The Texas government turned to Jones, ordering him to  use his Rangers to run Bass down. Seizing on the drama of the chase, the press dubbed the affair the “Bass War.” For four months, Bass led Jones and his Rangers on a wild chase through Texas. In July 1878, Jones learned that Bass was planning to rob the bank in Round Rock, Texas. When Bass did hit the bank, Jones and his Rangers were waiting. Bass was badly wounded in the ensuing gun battle, and he died several days later. Oddly it was Bass who later became a legend, portrayed as good-natured Robin Hood, while Jones has largely been forgotten. Jones continued to command the Frontier Battalion until he died of natural causes in 1881 at the age of 46.

use his Rangers to run Bass down. Seizing on the drama of the chase, the press dubbed the affair the “Bass War.” For four months, Bass led Jones and his Rangers on a wild chase through Texas. In July 1878, Jones learned that Bass was planning to rob the bank in Round Rock, Texas. When Bass did hit the bank, Jones and his Rangers were waiting. Bass was badly wounded in the ensuing gun battle, and he died several days later. Oddly it was Bass who later became a legend, portrayed as good-natured Robin Hood, while Jones has largely been forgotten. Jones continued to command the Frontier Battalion until he died of natural causes in 1881 at the age of 46.