disaster

Underground mining always has the potential to become deadly. The people of New Cumnock in Ayrshire, Scotland know that all too well after a mine collapsed, trapped 120 miners underground in Knockshinnoch Castle colliery. The tragic event became known as the Knockshinnoch disaster and it occurred in September 1950 in the village of New Cumnock, Ayrshire, Scotland. The disaster began when a glaciated lake filled with liquid peat and moss flooded the pit workings, trapping more than a hundred miners underground. That set of a rescue effort that lasted for several days. Teams worked non-stop to reach the trapped men. They did finally reach the men, but by the time they were able to reach them, three days later, thirteen men had died.

Underground mining always has the potential to become deadly. The people of New Cumnock in Ayrshire, Scotland know that all too well after a mine collapsed, trapped 120 miners underground in Knockshinnoch Castle colliery. The tragic event became known as the Knockshinnoch disaster and it occurred in September 1950 in the village of New Cumnock, Ayrshire, Scotland. The disaster began when a glaciated lake filled with liquid peat and moss flooded the pit workings, trapping more than a hundred miners underground. That set of a rescue effort that lasted for several days. Teams worked non-stop to reach the trapped men. They did finally reach the men, but by the time they were able to reach them, three days later, thirteen men had died.

The men who survived were all found together 24 hours after the disaster began, and the thirteen men who died had been separated from the main group. They were missing for two more days before they were finally found. When the lake flooded, it released a field about the size of a football field into the mine. The resulting crater was about 300 feet by 200 feet and about 50 feet deep. The crater then sent liquid peat cascading into the mine, effectively blocking any exit for the men.

Thankfully, the mine owners had the forethought to install a phone in the mine, and the miners were able to phone for help. There was no way of reaching them, but the rescuers knew they were still alive, so the rescue efforts began in earnest. Rescue workers decided the easiest way to get them out was through an abandoned mine, next door. It took until 10:30pm local time for the rescuers to clear a passage through the unused mine and break through the final 30-foot wall of coal and rock that separated the two collieries. The rescue team,  made up of hundreds of miners, firefighters, and trained rescuers, worked all day to shore up the walls and ceiling of the old mine. Because the tunnels were so cramped, the workers had to work in shifts, using fans to disperse the gas known as firedamp which accumulates in sealed mines. Firedamp is not poisonous, but it reduces the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere making breathing difficult, not to mention the fact that it is also highly flammable. At one point, a rescue worker collapsed because the air was so foul. He had to be helped to the surface. The situation was really getting serious, and time was running out. The danger of explosion meant the rescuers had to use hand tools to cut through the rock delaying the rescue even more.

made up of hundreds of miners, firefighters, and trained rescuers, worked all day to shore up the walls and ceiling of the old mine. Because the tunnels were so cramped, the workers had to work in shifts, using fans to disperse the gas known as firedamp which accumulates in sealed mines. Firedamp is not poisonous, but it reduces the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere making breathing difficult, not to mention the fact that it is also highly flammable. At one point, a rescue worker collapsed because the air was so foul. He had to be helped to the surface. The situation was really getting serious, and time was running out. The danger of explosion meant the rescuers had to use hand tools to cut through the rock delaying the rescue even more.

Everyone was very focused on saving the trapped men. The volunteers were working above ground, filling the crater made by the landslide with haystacks, trees and other materials to prevent any further slippage. They knew that is more peat fell into the hole, it could have blocked what little ventilation the trapped men had. The buried miners kept in phone contact every 15 minutes or so. They were told how they could help the rescue operation by digging carefully and slowly, so as not to let in a sudden rush of foul air from the unused pit, because they had no oxygen masks to help them breathe.

Finally, the wall was breached. To let the family and friends of the trapped men know that their loved ones were safe, a siren was sounded on the surface. Immediately, huge crowds gathered near the pithead. The police linked arms to form a protective cordon around the exit. The last thing the men needed was a rush of people the minute they reached the surface. Shortly before midnight, rescuers began taking food and drink into the pit for the miners. They had been underground for so long without nutrition and hydration. While the rescuers

were now with the men, the process of bringing them out of the mine would not be a speedy one. The rescue tunnel was only wide enough for one man to crawl through at a time, and many are said to be weak, so they waited while they ate and drank some water, before beginning the trek out. The Area Manager of the National Coal Board David McArdle has described the rescue operation as the greatest in the history of Scottish mining.

were now with the men, the process of bringing them out of the mine would not be a speedy one. The rescue tunnel was only wide enough for one man to crawl through at a time, and many are said to be weak, so they waited while they ate and drank some water, before beginning the trek out. The Area Manager of the National Coal Board David McArdle has described the rescue operation as the greatest in the history of Scottish mining.

Some years, it seems like we can struggle to find something to be thankful for on Thanksgiving Day. Of course, Thanksgiving Day isn’t the only day we should be thankful. We should be thankful every day, but t isn’t always easy. Take this year, for example. Inflation is high, there are “shortages” of necessities. Every day there is a warning of another new Covid strain. Jobs are scarce. Many people don’t see this as a year to be thankful for, and yet it is. It’s in times like these that we need to actually look for things to be thankful for. True, there may be many things that are difficult right now, but if we look, we can find something that we are thankful for…and being thankful in our current circumstances is of vital importance.

Some years, it seems like we can struggle to find something to be thankful for on Thanksgiving Day. Of course, Thanksgiving Day isn’t the only day we should be thankful. We should be thankful every day, but t isn’t always easy. Take this year, for example. Inflation is high, there are “shortages” of necessities. Every day there is a warning of another new Covid strain. Jobs are scarce. Many people don’t see this as a year to be thankful for, and yet it is. It’s in times like these that we need to actually look for things to be thankful for. True, there may be many things that are difficult right now, but if we look, we can find something that we are thankful for…and being thankful in our current circumstances is of vital importance.

The Apostle Paul wrote in Philippians 4:12-13, “I know both how to have a little, and I know how to have a lot. In any and all circumstances I have learned the secret of being content—whether well fed or hungry, whether in abundance or in need. I am able to do all things through Him who strengthens me.” Now, there is the epitome of being thankful…being thankful when we have little and when we have much. All too often, we think that we have to be in abundance in order to have anything to be thankful for. Of course, it’s easy to be thankful when you are “rolling in dough,” but not so easy when you’re not. Still, we should be thanking God every day, for everything…not just for the big things that our greed wants, but for things like life, family, happiness, and health. These are the things that we often take for granted, but that we should always be thankful for.

Some years it is harder to find things to be thankful for…it’s true, but I think that in the years when we have to think about it or search for a reason to be thankful, we can actually find ourselves feeling even more thankful

than in the years that seem to have plenty. I think of families who have survived a disaster. Their home is gone, but they are alive. Do you think that they are thankful? Absolutely!! We might think, but their home is gone, how can they not feel loss? Well, the answer is, they do feel a loss, but they also feel thankful, because their family is intact. Sometimes, that is the sweetest tone of thankfulness there is.

than in the years that seem to have plenty. I think of families who have survived a disaster. Their home is gone, but they are alive. Do you think that they are thankful? Absolutely!! We might think, but their home is gone, how can they not feel loss? Well, the answer is, they do feel a loss, but they also feel thankful, because their family is intact. Sometimes, that is the sweetest tone of thankfulness there is.

It seems an impossible task, to keep a disaster a secret, and yet that is exactly what the Soviet Union tried to do when disaster struck on April 26, 1986, at the No. 4 reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near the city of Pripyat in the north of the Ukrainian SSR. Chernobyl is considered the worst nuclear disaster in history. In terms of cost and casualties, and it is one of only two nuclear energy accidents rated at seven, which is the maximum severity, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The other disaster was the well known 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan that was caused by a tsunami.

It seems an impossible task, to keep a disaster a secret, and yet that is exactly what the Soviet Union tried to do when disaster struck on April 26, 1986, at the No. 4 reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near the city of Pripyat in the north of the Ukrainian SSR. Chernobyl is considered the worst nuclear disaster in history. In terms of cost and casualties, and it is one of only two nuclear energy accidents rated at seven, which is the maximum severity, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The other disaster was the well known 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan that was caused by a tsunami.

On April 28, 1986, two days after monitoring stations in Sweden, Finland and Norway began reporting sudden high discharges of radioactivity in the atmosphere, the Soviet Union finally broke the news by way of their official news agency, Tass. Two days!! In the realm of nuclear contamination, two days is an eternity!! When the Soviet Union finally told the world, Tass simply said there had been an accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine. They didn’t say they had tried to hide it, but two days of no response tells me they did. The initial emergency response, together with later decontamination of the environment, ultimately involved more than 500,000 personnel and cost an estimated 18 billion Soviet rubles, which is roughly $68 billion US dollars as of the dollar value in 2019.

It was determined that the accident had started during a safety test on an RBMK-type nuclear reactor. During testing a simulation of an electrical power outage was used to help create a safety procedure for maintaining reactor cooling water circulation until the back-up electrical generators could provide power. These units had been tested three times since 1982, but they had failed to provide a solution. On this fourth attempt, an unexpected 10-hour delay meant that an unprepared operating shift was on duty. The power unexpectedly dropped to a near-zero level during the planned decrease of reactor power in preparation for the electrical test. The operators were only able to partially restore the specified test power, putting the reactor in an unstable condition. This risk was not made evident in the operating instructions, so the operators proceeded with the electrical test. Upon test completion, the operators triggered a reactor shutdown, but a combination of unstable conditions and reactor design flaws caused an uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction instead.

The failure caused a large amount of energy to be suddenly released, followed by two explosions that ruptured  the reactor core and destroyed the reactor building. One was a highly destructive steam explosion from the vaporizing superheated cooling water. The other explosion could have been another steam explosion or a small nuclear explosion, like a nuclear fizzle. The explosions were followed immediately by an open-air reactor core fire that released considerable airborne radioactive contamination for about nine days. The contamination fell onto parts of the USSR and western Europe, especially 10 miles away in Belarus, where around 70% landed, before finally being contained on May 4, 1986. In addition to the contamination released by the explosions, the fire gradually released about the same amount of contamination as did the initial explosion. As a result of rising radiation levels in surrounding regions, a 6.2 mile radius exclusion zone was created 36 hours after the accident. About 49,000 people were evacuated from the area, primarily the citizens of Pripyat. Later the exclusion zone was increased to 19 mile radius, and an additional 68,000 people were evacuated from the wider area.

the reactor core and destroyed the reactor building. One was a highly destructive steam explosion from the vaporizing superheated cooling water. The other explosion could have been another steam explosion or a small nuclear explosion, like a nuclear fizzle. The explosions were followed immediately by an open-air reactor core fire that released considerable airborne radioactive contamination for about nine days. The contamination fell onto parts of the USSR and western Europe, especially 10 miles away in Belarus, where around 70% landed, before finally being contained on May 4, 1986. In addition to the contamination released by the explosions, the fire gradually released about the same amount of contamination as did the initial explosion. As a result of rising radiation levels in surrounding regions, a 6.2 mile radius exclusion zone was created 36 hours after the accident. About 49,000 people were evacuated from the area, primarily the citizens of Pripyat. Later the exclusion zone was increased to 19 mile radius, and an additional 68,000 people were evacuated from the wider area.

When the reactor exploded, two of the reactor operating staff lost their lives instantly. Crews rushed to put out the fire, stabilize the reactor, and cleanup the ejected nuclear core. As a result of the disaster and immediate response, 134 station staff and firemen were hospitalized with acute radiation syndrome due to absorbing high doses of ionizing radiation. In the days to months afterward 28 of these 134 people died, and approximately 14 suspected radiation-induced cancer deaths followed within the next 10 years. Significant cleanup operations were taken in the exclusion zone to deal with local fallout, and the exclusion zone was made permanent. The cities in the zone remain abandoned.

By 2011, an excess of 15 childhood thyroid cancer deaths were documented among the wider population. The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) has reviewed all the published research on the incident multiple times, and found that at present, fewer than 100 documented deaths are likely to be attributable to increased exposure to radiation. Of course, there is no way to be sure of that information, because “determining the total eventual number of exposure related deaths is uncertain based on the linear no-threshold model, a contested statistical model, which has also been used in estimates of low level radon and air pollution exposure.” When the expected deaths is viewed in “model predictions with the greatest confidence values of the eventual total death toll in the decades ahead from Chernobyl releases vary, from 4,000 fatalities when solely assessing the three most contaminated former Soviet states, to about 9,000 to 16,000 fatalities when assessing the total continent of Europe. In an effort to reduce the spread of radioactive contamination from the wreckage and protect it from weathering, the protective Chernobyl Nuclear  Power Plant sarcophagus was built by December 1986. It also provided radiological protection for the crews of the undamaged reactors at the site, which continued operating. Due to the continued deterioration of the sarcophagus, it was further enclosed in 2017 by the Chernobyl New Safe Confinement, a larger enclosure that allows the removal of both the sarcophagus and the reactor debris, while containing the radioactive hazard. Nuclear clean-up is scheduled for completion in 2065.” It is my opinion that if they had acted immediately to evacuate the people in surrounding areas, they might have reduced the number of deaths substantially. Keeping the accident a secret for two days was insane, and very likely criminal.

Power Plant sarcophagus was built by December 1986. It also provided radiological protection for the crews of the undamaged reactors at the site, which continued operating. Due to the continued deterioration of the sarcophagus, it was further enclosed in 2017 by the Chernobyl New Safe Confinement, a larger enclosure that allows the removal of both the sarcophagus and the reactor debris, while containing the radioactive hazard. Nuclear clean-up is scheduled for completion in 2065.” It is my opinion that if they had acted immediately to evacuate the people in surrounding areas, they might have reduced the number of deaths substantially. Keeping the accident a secret for two days was insane, and very likely criminal.

Rain…it waters the earth, and as we all know, without it, we could not survive. Nevertheless, as vital as water is to life on this planet, too much of it can be deadly. People can drink too much water, we can over-water our plants, and too much rain can bring flooding. Such was the case on July 13, 1951. Above-average rainfall began in June and continued through July 13th, dumping well over 25 inches on some areas in eastern Kansas. From July 9th to 13th, nearly 6 inches of rain fell. The Kansas, Neosho, and Verdigris rivers began taking on more water than their normal carrying capacity a couple of days into the storm, but as the rain persisted, flooding began all over the region.

Rain…it waters the earth, and as we all know, without it, we could not survive. Nevertheless, as vital as water is to life on this planet, too much of it can be deadly. People can drink too much water, we can over-water our plants, and too much rain can bring flooding. Such was the case on July 13, 1951. Above-average rainfall began in June and continued through July 13th, dumping well over 25 inches on some areas in eastern Kansas. From July 9th to 13th, nearly 6 inches of rain fell. The Kansas, Neosho, and Verdigris rivers began taking on more water than their normal carrying capacity a couple of days into the storm, but as the rain persisted, flooding began all over the region.

The major towns of Manhattan, Topeka and Lawrence took the biggest hit. As is  the case in any area where absorption is hampered by cement and asphalt, the rain could not soak in, and the ground was are already saturated anyway. The rain had nowhere to go, and the area was in trouble. Prior to the July 13 river crest, previous highs were dwarfed by four to nine feet. Two million acres of farmland were lost to the flood, which would trigger a crisis of its own, by a shortage of food. The flooding also caused fires and explosions in refinery oil tanks on the banks of the Kansas River. Passenger trains traveling through the area were stuck for nearly four days. In all, $760 million in damages were caused by the flood, and 500,000 people were left homeless, while 24 people died in the disaster. It was the greatest destruction from flooding in the Midwestern United States up to that time.

the case in any area where absorption is hampered by cement and asphalt, the rain could not soak in, and the ground was are already saturated anyway. The rain had nowhere to go, and the area was in trouble. Prior to the July 13 river crest, previous highs were dwarfed by four to nine feet. Two million acres of farmland were lost to the flood, which would trigger a crisis of its own, by a shortage of food. The flooding also caused fires and explosions in refinery oil tanks on the banks of the Kansas River. Passenger trains traveling through the area were stuck for nearly four days. In all, $760 million in damages were caused by the flood, and 500,000 people were left homeless, while 24 people died in the disaster. It was the greatest destruction from flooding in the Midwestern United States up to that time.

A often happen, tragedy brings change. Following the great 1951 flood, a series of reservoirs and levees were constructed all over the area. In 1993, these were credited with minimizing the damage from another record flood. Water is an element that is necessary for life, but lest we forget, water in an overabundance can kill and destroy. People need to pay attention to evacuation warnings, and get out of an area where a flood is eminent. You may lose some things, but if you leave the area, you will most likely to walk away unscathed, and as we know, things can be predicted, and those who head out of unsafe areas will most likely live to tell the tale.

When disaster strikes, and homes are in ruin, people try to come together to help return a sense of normalcy to the people affected by the disaster. Disasters happen quickly, and the devastation is often heavy. It is a difficult thing to help people heal. While one disaster or event is often the same as another in terms of damage, something we somehow don’t connect to that same kind of devastation, is war. I’m not sure why, but when I think of war,I picture a battle held in the middle of a vast desert, with no civilization in sight. of course, when I really think about it, I now that is not reality, but rather my mind trying to fit war into a box of civility. In reality, there is nothing civil about war. Gun shots, bombs, and land mines aren’t picky about who they hit. Soldier or civilian…all are fair game in a war. And towns…well, there is often little to nothing left after a bomb hits.

When disaster strikes, and homes are in ruin, people try to come together to help return a sense of normalcy to the people affected by the disaster. Disasters happen quickly, and the devastation is often heavy. It is a difficult thing to help people heal. While one disaster or event is often the same as another in terms of damage, something we somehow don’t connect to that same kind of devastation, is war. I’m not sure why, but when I think of war,I picture a battle held in the middle of a vast desert, with no civilization in sight. of course, when I really think about it, I now that is not reality, but rather my mind trying to fit war into a box of civility. In reality, there is nothing civil about war. Gun shots, bombs, and land mines aren’t picky about who they hit. Soldier or civilian…all are fair game in a war. And towns…well, there is often little to nothing left after a bomb hits.

During World War II, London was often the targets of the German Luftwaffe, and the bombs they dropped, devastated many parts of London. From September 7, 1940, London was systematically bombed by the Luftwaffe for 56 out of the following 57 days and nights, in what was called “The Blitz.” Most notable was a large daylight attack against London on September 15th. Of course, these weren’t the only bombings, and the people of London didn’t know when or if it was safe to be out of the bomb shelters. Life in London had taken on eerie gloom,as people continued to seek refuge in the bomb shelters, because that was the only safe place to be. The biggest problem was that the bomb shelters were also gloomy, boring, and generally depressing. The children probably suffered the most, because kids don’t really understand all this hatred and killing. Their world had been turned upside down…and they didn’t know why.

By the end of 1940, 24,000 civilians had been killed in the Blitz and hundreds of thousands made homeless. In November, German bombers had obliterated Coventry city center and there had been particularly fierce raids on Manchester and Liverpool in the days leading up to Christmas. The public were now mourning the loss of their loved ones on the home front and in combat, as well as praying for the 41,000 British soldiers captured on the continent, but it was the children, in my mind, who suffered the most. Their childlike innocence was completely destroyed, along with their homes. Their parents, and other adults made the decision to change their little world, even if it was only for a short time. They didn’t have much, but they put together whatever they could to lift the spirits of these scared children. Christmas parties were held for the children and the shelter walls were decorated with paper chains and decorations, while amateur singing nights, discussion groups, and sewing circles were held regularly.

In order to avoid the bombs, many families spent some of the holidays in air-raid shelters and other places of refuge. They decked out their temporary homes with makeshift decorations…and very short Christmas trees because of the height of the shelters. Even if gas or electricity was available, Christmas dinner would have still been an amazing feat, because turkey was so expensive. Most people made do with other cuts of meat, which were still expensive. A family of four’s weekly meat ration probably wouldn’t even cover the cost of a small chicken. One alternative was home-raised chickens or rabbits, much to the shock of young children who often regarded them as pets. Home-grown vegetables and chutneys would have also made the table. Rations were  scrimped and saved including ham, bacon, butter, suet, and margarine. The tea and sugar rations were increased in the week before Christmas. Very little fruit was imported and nuts were very costly. Consequently, cooks had to improvise Christmas cakes and puddings devoid of dried fruit and marzipan, using instead sponge or other unlikely ingredients. Alcohol was available but, horribly expensive. And there would be no after-dinner French cheeses or brandy due to the German occupation. It was a poor Christmas party in comparison to those in the past, but it served to remind all the people that Christmas is more about the blessings in life, than it is about the things we are given.

scrimped and saved including ham, bacon, butter, suet, and margarine. The tea and sugar rations were increased in the week before Christmas. Very little fruit was imported and nuts were very costly. Consequently, cooks had to improvise Christmas cakes and puddings devoid of dried fruit and marzipan, using instead sponge or other unlikely ingredients. Alcohol was available but, horribly expensive. And there would be no after-dinner French cheeses or brandy due to the German occupation. It was a poor Christmas party in comparison to those in the past, but it served to remind all the people that Christmas is more about the blessings in life, than it is about the things we are given.

A sudden downpour near Terry, Montana on the evening of June 19, 1938 caused a flash flooding of the Custer Creek that would lead to a disaster before the night was over. Earlier in the day, a track walker was sent out the check the rail lines near Custer Creek which was located near the town of Terry, Montana. After his inspection, he reported to his superiors that the conditions were dry, and there were no problems with the tracks.

A sudden downpour near Terry, Montana on the evening of June 19, 1938 caused a flash flooding of the Custer Creek that would lead to a disaster before the night was over. Earlier in the day, a track walker was sent out the check the rail lines near Custer Creek which was located near the town of Terry, Montana. After his inspection, he reported to his superiors that the conditions were dry, and there were no problems with the tracks.

That was true at the time, but within a few hours, a sudden downpour overwhelmed Custer Creek. A small winding river, Custer Creek runs through 25 miles of the Great Plains before depositing into the Yellowstone River. Small streams like Custer Creek are prone to flash floods, because they don’t have  the capacity to handle any big influx of water, and their banks can quickly and easily be overtaken during heavy rains. As the water came rushing down stream, it washed out a bridge used by the trains. When the Olympian Special came through, it went crashing into the raging waters with no warning. Two sleeper cars were buried in the muddy waters. The night was pitch black seriously hampering rescue efforts. In all, 46 people lost their lives, and 60 others were seriously injured. The rear cars stayed above the water, but scores of passengers were seriously injured. They could not be evacuated until the following morning. I can’t even begin to imagine how awful that was.

the capacity to handle any big influx of water, and their banks can quickly and easily be overtaken during heavy rains. As the water came rushing down stream, it washed out a bridge used by the trains. When the Olympian Special came through, it went crashing into the raging waters with no warning. Two sleeper cars were buried in the muddy waters. The night was pitch black seriously hampering rescue efforts. In all, 46 people lost their lives, and 60 others were seriously injured. The rear cars stayed above the water, but scores of passengers were seriously injured. They could not be evacuated until the following morning. I can’t even begin to imagine how awful that was.

That was a tough week for Montana. Just a few days later, Black Eagle saw “torrents of water” that floated  furniture in the house of Sam Tadich, the sheriff had to help a rescue effort, the road to Giant Springs washed away and water was up to cows’ flanks around the Sun River. Havre’s worst flood came in June 22, 1938, when a cloudburst in the Bear Paw Mountains sent out a wall of water. Ten people were killed. Floating train cars were wedged under the viaduct, 10 miles of highway were underwater between Laredo and Box Elder, with a bridge washed out, the Havre Daily News reported. Rain is a good thing, but too much rain, coming too fast can devastate an area, especially one with a creek or river, in a very short time, and for Montana, it was a very rainy week, making it a very tough week.

furniture in the house of Sam Tadich, the sheriff had to help a rescue effort, the road to Giant Springs washed away and water was up to cows’ flanks around the Sun River. Havre’s worst flood came in June 22, 1938, when a cloudburst in the Bear Paw Mountains sent out a wall of water. Ten people were killed. Floating train cars were wedged under the viaduct, 10 miles of highway were underwater between Laredo and Box Elder, with a bridge washed out, the Havre Daily News reported. Rain is a good thing, but too much rain, coming too fast can devastate an area, especially one with a creek or river, in a very short time, and for Montana, it was a very rainy week, making it a very tough week.

These days, scientist and inventors have collaborated to develop early warning systems for just about any possible disaster, and when everything works as it should, and people heed the warnings, loss of life can often be avoided. Having the technology is great, but technology can’t make human beings do the right things…unfortunately. On May 22, 1960, twelve years after tsunami warnings were developed, and with the warning system in good working order, a massive 9.5 earthquake struck off the coast of Chili. It was the largest earthquake ever recorded. Unfortunately, we don’t really have an earthquake warning, and so without warning, 1655 people lost their lives in Chili and 3,000 injured in the quake. Two million people were made homeless, and damage was estimated at $550 million. The earthquake, involving a severe plate shift, caused a large displacement of water off the coast of southern Chile at 3:11pm. Traveling at speeds in excess of 400 miles per hour, the tsunami moved west and north. On the west coast of the United States, the waves caused an estimated $1 million in damages, but were not deadly. Everyone assumed that the worst was over.

These days, scientist and inventors have collaborated to develop early warning systems for just about any possible disaster, and when everything works as it should, and people heed the warnings, loss of life can often be avoided. Having the technology is great, but technology can’t make human beings do the right things…unfortunately. On May 22, 1960, twelve years after tsunami warnings were developed, and with the warning system in good working order, a massive 9.5 earthquake struck off the coast of Chili. It was the largest earthquake ever recorded. Unfortunately, we don’t really have an earthquake warning, and so without warning, 1655 people lost their lives in Chili and 3,000 injured in the quake. Two million people were made homeless, and damage was estimated at $550 million. The earthquake, involving a severe plate shift, caused a large displacement of water off the coast of southern Chile at 3:11pm. Traveling at speeds in excess of 400 miles per hour, the tsunami moved west and north. On the west coast of the United States, the waves caused an estimated $1 million in damages, but were not deadly. Everyone assumed that the worst was over.

Nevertheless, warnings were sent to the Hawaiian islands. The Pacific Tsunami Warning System properly and warnings were issued to Hawaiians six hours before the wave’s expected arrival. The response of some people, however, was reckless and irresponsible. Some people ignored the warnings, and others actually headed to the coast in order to view the wave. Arriving 15 hours after the quake, only a minute after predicted, the tsunami destroyed Hilo Bay, on the island of Hawaii. Thirty five foot waves bent parking meters to the ground and wiped away most buildings, destroying or damaging more than 500 homes and businesses. A 10 ton tractor was swept out to sea. Reports indicate that the 20 ton boulders making up the sea wall were moved 500 feet. Sixty-one people died in Hilo, the worst-hit area of the island chain. Damage was estimated at $75 million. This tsunami caused little damage elsewhere in the islands, where wave heights were in the 3-17 foot range. The tsunami continued to race further west across the Pacific. Ten thousand miles away from the earthquake’s epicenter. Japan, received warning, but wasn’t able to warn the people in harm’s way. At about 6pm, more than a day after the quake, the tsunami hit the Japanese islands of Honshu and Hokkaido. The  crushing wave killed 180 people, left 50,000 more homeless and caused $400 million in damages. The Philippines, also hit, saw 32 people dead or missing.

crushing wave killed 180 people, left 50,000 more homeless and caused $400 million in damages. The Philippines, also hit, saw 32 people dead or missing.

Tsunami warnings definitely save lives, but only if people will heed the warnings. As long as people decide that the warning doesn’t apply to them, and give in to their curiosity to go have a look, there will continue to be deaths. It seems a great shame that inventors and scientist work so hard to make a warning to save lives, and then some people refuse to do what is necessary to be safe after they have been warned. I simply don’t understand how people can ignore these warnings and take a chance with their lives.

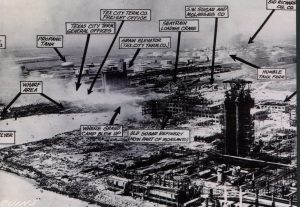

It was a typical day in Texas City, Texas…a port city in Galveston Bay. April was always warm, in the mid-70s, so it was perfect outdoor weather. Fires around the docks were a fairly common occurrence in Texas City, and it was not unusual for residents to travel down to the docks to watch the fires and the firemen working. Fires tend to attract the casual observer as well as the local news agencies. This day started out just as any other typical Texas day, but all that would change very soon. On the morning of April 16, 1947 a fire broke out on the S.S. Grandcamp. The fire produced a dense, brilliantly colored smoke that could be seen all over town. On board Grandcamp, among other things, was a supply of ammonium nitrate, which was producing the brilliant colors. The ship was docked in the Texas City port, so the smoke could be seen all over town. This fire, like any other, brought anybody who had any free time down to the dock to watch the action. This would be a fatal mistake for many of the bystanders.

It was a typical day in Texas City, Texas…a port city in Galveston Bay. April was always warm, in the mid-70s, so it was perfect outdoor weather. Fires around the docks were a fairly common occurrence in Texas City, and it was not unusual for residents to travel down to the docks to watch the fires and the firemen working. Fires tend to attract the casual observer as well as the local news agencies. This day started out just as any other typical Texas day, but all that would change very soon. On the morning of April 16, 1947 a fire broke out on the S.S. Grandcamp. The fire produced a dense, brilliantly colored smoke that could be seen all over town. On board Grandcamp, among other things, was a supply of ammonium nitrate, which was producing the brilliant colors. The ship was docked in the Texas City port, so the smoke could be seen all over town. This fire, like any other, brought anybody who had any free time down to the dock to watch the action. This would be a fatal mistake for many of the bystanders.

The ammonium nitrate on board the Grandcamp detonated at 9:12 am, blowing he ship apart and sending the cargo of peanuts, tobacco, twine, bunker oil and the remaining bags of ammonium nitrate 2,000 to 3,000 feet into the air. Fireballs streaked across the sky and could be seen for miles across Galveston Bay as molten ship fragments erupted out of the pier. The blast sent a fifteen foot tidal wave crashing onto the dock and flooding the surrounding area. Windows were shattered in Houston, 40 miles to the north, and people in Louisiana felt the shock 250 miles away. Most of the buildings closest to the blast were flattened, and there were many more that had doors and roofs blown off. The Monsanto plant which was only three hundred feet away, was destroyed by the blast. Most of the Texas City Terminal Railways’ warehouses along the docks were destroyed. Hundreds of employees, pedestrians and bystanders were killed. At the time of the Grandcamp’s explosion, only two additional vessels were docked in port…the S.S. High Flyer and the Wilson B. Keene, both American C-2 cargo ships similar to the Grandcamp.

The intensity of the blast sent shrapnel tearing into the surrounding area. Flaming debris ignited giant tanks full  of oil and chemicals stored at the refineries, causing a set of secondary fires and smaller explosions. The Longhorn II, a barge anchored in port, was lifted out of the water by the sheer force of the explosion and landed 100 feet away on the shore. Buildings blazed long after the initial explosion, provoking large scale emergency relief efforts throughout the day, that night, and into the following day. The fires in nearby industrial buildings and chemical plants spread the destruction even farther. The chief and 27 firefighters from the Texas City Fire Department were killed in the initial blast. Official estimates put the death toll at 567 and injuries at more than 5,000. Some of the dead were never identified, and some may never have been found at all.

of oil and chemicals stored at the refineries, causing a set of secondary fires and smaller explosions. The Longhorn II, a barge anchored in port, was lifted out of the water by the sheer force of the explosion and landed 100 feet away on the shore. Buildings blazed long after the initial explosion, provoking large scale emergency relief efforts throughout the day, that night, and into the following day. The fires in nearby industrial buildings and chemical plants spread the destruction even farther. The chief and 27 firefighters from the Texas City Fire Department were killed in the initial blast. Official estimates put the death toll at 567 and injuries at more than 5,000. Some of the dead were never identified, and some may never have been found at all.

The blast registered on a seismograph as far away as Denver, Colorado. Dockworker Pete Suderman remembers flying thirty feet as the blast carried him and several of the dock’s three-inch wooden planks across the pier. Nattie Morrow was in her home with her two children and sister-in-law Sadie. She watched the billowing smoke near the Monsanto plant from her back porch just prior to the blast. “Suddenly a thundering boom sounded, and seconds later the door ripped off its facing, skidded across the kitchen floor, and slammed down onto the table where I sat with the baby. The house toppled to one side and sat off its piers at a crazy angle. Broken glass filled the air, and we didn’t know what was happening.”

At the time of the explosion, phone services in Texas City were not working because of a telephone operators’ strike. When the operators learned of the accident, they quickly went back to work, but the strike caused an initial delay in coordinating rescue efforts. Once operators began calling for help, rescue workers from all over the area began responding immediately. The U.S. Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Marine Reserve and the Texas National Guard all sent personnel, including doctors, nurses and ambulances. The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston sent doctors, nurses, and medical students. Firefighters from Galveston, Houston, Fort Crockett, Ellington Field, and surrounding towns arrived to help. The cities of Galveston, Houston and San Antonio sent policemen to assist the Texas City Police Department in maintaining order after the explosion. The U.S. Army flew in blood  plasma, gas masks, food, and other supplies, provided bull-dozers to begin clearing the wreckage, and set up temporary housing for the survivors at Camp Wallace in Hitchcock. The Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Boy and Girl Scouts of America sent a flood of volunteers who provided first aid, food, water and comfort to city residents. Volunteers from other local organizations, and others who were not part of any organization, felt compelled to help. There was no operational hospital in Texas City at the time of the disaster, so volunteers converted city hall and chamber of commerce buildings into makeshift infirmaries. Many wounded were evacuated to John Sealy Hospital in Galveston, the hospital at Fort Crockett, and hospitals in Houston.

plasma, gas masks, food, and other supplies, provided bull-dozers to begin clearing the wreckage, and set up temporary housing for the survivors at Camp Wallace in Hitchcock. The Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Boy and Girl Scouts of America sent a flood of volunteers who provided first aid, food, water and comfort to city residents. Volunteers from other local organizations, and others who were not part of any organization, felt compelled to help. There was no operational hospital in Texas City at the time of the disaster, so volunteers converted city hall and chamber of commerce buildings into makeshift infirmaries. Many wounded were evacuated to John Sealy Hospital in Galveston, the hospital at Fort Crockett, and hospitals in Houston.

Airplane disasters are always horrible, but sometimes the circumstances just don’t seem to fit the disaster. During World War II, the US Army Air Forces were stationed in bases around the world, mostly for quick access to air targets, but with the added benefit for the people in the area of some protection from enemy forces. Just having the planes in the area tended to be a deterrent for the enemy planes, who did not want to be attacked in great numbers. Planes like the B-17, B-24, and others regularly flew over the towns near their bases. One such flight…unfortunately ended in a disaster.

Airplane disasters are always horrible, but sometimes the circumstances just don’t seem to fit the disaster. During World War II, the US Army Air Forces were stationed in bases around the world, mostly for quick access to air targets, but with the added benefit for the people in the area of some protection from enemy forces. Just having the planes in the area tended to be a deterrent for the enemy planes, who did not want to be attacked in great numbers. Planes like the B-17, B-24, and others regularly flew over the towns near their bases. One such flight…unfortunately ended in a disaster.

On August 23, 1944, a pair of newly refurbished B-24 Liberator heavy bombers were being taken on a test flight, prior to their delivery to the 2nd Combat Division. The planes departed US Army Air Force Base Air Depot 2 and Warton Aerodrome at 10:30am. Due to an impending potentially violent storm, both planes were recalled. Unfortunately, by the time they returned, to the vicinity of the Aerodrome, the wind and rain had significantly reduced visibility. Newspaper reports detailed wind velocities approaching 60 mph, water spouts in the Ribble Estuary and flash flooding in Southport and Blackpool. As the two planes flew in formation from the west toward runway 08, the pilot of the B-24H-20-CF Liberator, US aircraft serial number 42-50291, named “Classy Chassis II”, 1st Lieutenant John Bloemendal, reported to the control tower that he was aborting landing at the last moment and would “go around.”

Shortly afterwards, and out of visibility of the second aircraft, the aircraft hit the village of Freckleton, just east of the airfield. As it came down, the B-24 Liberator heavy bomber crashed into the center of the village of Freckleton, Lancashire, England. The aircraft crashed into the Holy Trinity Church of England School, demolishing three houses and the Sad Sack Snack Bar. The death toll was 61, including 38 children.

The plane was already flying very low, and for whatever reason, the wings were very nearly vertical. The plane’s right wing tip hit a tree top, and was ripped away as it impacted the corner of a building. The rest of the wing continued, plowing along the ground and through a hedge. The fuselage of the 25 ton bomber continued, partly demolishing three houses and the Sad Sack Snack Bar, before crossing Lytham Road and bursting into flames. A part of the aircraft hit the infants’ wing of Freckleton Holy Trinity School. Fuel from the ruptured tanks ignited and produced a sea of flames. In the school, 38 schoolchildren and six adults were killed. The clock in one classroom stopped at 10:47 am. In the Sad Sack Snack Bar, which catered specifically to American servicemen from the air-base, 14 were killed…seven Americans, four Royal Air Force airmen and three civilians. The three crew members on the B-24 were also killed.

The official report stated that the exact cause of the crash was unknown, but concluded that the pilot had not fully realized the danger the storm posed until underway in his final approach, by which time he had insufficient altitude and speed to maneuver given the probable strength of wind and downdrafts that must have prevailed. Structural failure of the aircraft in the extreme conditions was not ruled out, although the complete destruction of the B-24 prevented any meaningful investigation. Because many of the pilots coming to the England commonly believed that British storms were little more than showers, it was recommended that all US trained pilots should be emphatically warned of the dangers of British thunderstorms. A memorial garden and

children’s playground were opened in August 1945, in memory of those lost, the money for the playground equipment having been raised by American airmen at the Warton airbase. A fund for a memorial hall was started, and the hall was finally opened in September 1977. Another memorial in the village churchyard was placed at the accident site in 2007. The plane that had come to signify protection for the area people, in the end spelled friendly disaster.

children’s playground were opened in August 1945, in memory of those lost, the money for the playground equipment having been raised by American airmen at the Warton airbase. A fund for a memorial hall was started, and the hall was finally opened in September 1977. Another memorial in the village churchyard was placed at the accident site in 2007. The plane that had come to signify protection for the area people, in the end spelled friendly disaster.

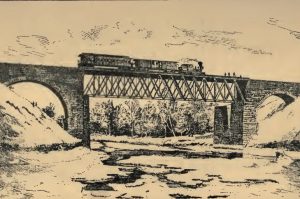

Through the centuries, new designs were developed to build things we needed. As the railroad moved across the nation, track laying came across deep gorges and flat plains. Of course, the flat plains were easy to deal with, and trains could simply go around any hills in the area, but the rivers and gullies were a bigger problem. They needed bridges, and so Charles Collins and Amasa Stone jointly designed a bridge to be used at Ashtabula, Ohio. It was the first Howe-type wrought iron truss bridge built. Collins was worried about the bridge, thinking that it was “too experimental” and needed further evaluation. Nevertheless, higher powers prevailed, and the bridge was built. Collins had been right to be concerned. The bridge lasted just 11 years before it collapsed.

Through the centuries, new designs were developed to build things we needed. As the railroad moved across the nation, track laying came across deep gorges and flat plains. Of course, the flat plains were easy to deal with, and trains could simply go around any hills in the area, but the rivers and gullies were a bigger problem. They needed bridges, and so Charles Collins and Amasa Stone jointly designed a bridge to be used at Ashtabula, Ohio. It was the first Howe-type wrought iron truss bridge built. Collins was worried about the bridge, thinking that it was “too experimental” and needed further evaluation. Nevertheless, higher powers prevailed, and the bridge was built. Collins had been right to be concerned. The bridge lasted just 11 years before it collapsed.

On December 28, 1876, a Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway train…the Pacific Express left New York. It struggled along through the drifts and the blinding storm. The train was pulling into Ashtabula, Ohio, shortly before 8:00pm on December 29, 1876, several hours behind schedule. The eleven cars were a heavy burden to the two engines. The leading locomotive broke through the drifts beyond the ravine, and rolled on across the bridge at Ashtabula at less than ten miles an hour. The head lamp could barely be seen because the air was thick with the driving snow. The leading engine reached solid ground, and the engineer had just given it steam…when something in the undergearing of the bridge snapped.

What followed was a horror beyond horrors…not only for the victims, but for the rescuers as well…maybe even more so for the rescuers. As the bridge crumbled beneath the weight of the train, the train and its 159 passengers fell 70 feet into the river below. More than 90 people, passengers and crew, were killed when the train hit the river and ignited into a huge ball of flames. Only the lead engine escaped the fall. As the bridge fell, the engineer gave it a quick head of steam, which tore the draw head from its tender, and the liberated engine shot forward and buried itself in the snow. The engineer escaped with a broken leg. The proportions of the Ashtabula horror are still only approximately known. Daylight, brought with it the opportunity to find and count the saved. It also revealed the fact that two out of every three passengers on the train were lost. Of the 160 passengers who the injured conductor reports as having been on board, fifty nine were found or accounted for as surviving. The remaining 100, burned to ashes or shapeless lumps of charred flesh, were lying under the ruins of the bridge and train. Every possible element of horror was there. First came the crash of the bridge, the agonizing moments of suspense as the seven laden cars plunged down their fearful leap to the icy riverbed. Then the fire, that devoured all that had been left alive by the crash. The water that gurgled up from under the broken ice brought with it another form of death. And finally, the biting blast of freezing air filled with snow, that froze those who had escaped the water and fire.

For the rescuers, the horror had just begun. I can’t think of anything worse than seeing those bodies after they were horribly mangled, drowned, and burned…some beyond recognition, some completely cremated. The number of persons killed cannot be accurately stated, because it is not known exactly how many there were on the train. It is supposed that some of the bodies were entirely consumed in the flames, as well. The official list of those killed and those who have died of their injuries, gives the number as fifty five, but it is suspected to be somewhat higher. There is no death list to report…and in fact, there can be none. There are no remains that can ever be identified. The three charred, shapeless lumps recovered were burned beyond recognition. For the rest, there are piles of white ashes in which were found the crumbling particles of bones. In other places masses of black, charred debris, half under water, which may contain fragments of bodies, but nothing that resembled a human body. It is thought that there may have been a few corpses under the ice, as there were women and children who jumped into the water and sank, but none have been recovered. Periodically, as people began looking for people that were missing around the country, and they were able to place them, as possibly on the train, more supposed victims have been identified…at least there is the possibility that they were a victim.

The Ashtabula, Ohio Railroad Disaster, often referred to simply as the Ashtabula Disaster or the Ashtabula Horror, was one of the worst railroad disasters in American history. The event occurred just 100 yards from the railroad station at Ashtabula, Ohio. It’s topped only by the Great Train Wreck of 1918 in Nashville, Tennessee. Charles Collin, the chief engineer, who knew as few men did the defects of that bridge, but was powerless to repair them, had been listening for this very crash for years. Collins, locked himself in his bedroom and shot himself while the inquest was in progress rather than tell the world all he believed he knew. Collins was found  dead in his bedroom of a gunshot wound to the head. He had tendered his resignation to the Board of Directors the previous Monday. Collins was believed to have committed suicide out of grief and feeling partially responsible for the tragic accident, however, a police report at the time suggested the wound had not been self inflicted. Documents discovered in 2001 and an examination of Collins’ skull suggest that he had indeed been murdered. Amasa Stone committed suicide seven years later after experiencing financial difficulties with some foundries he had interests in, suffering from severe ulcers that kept him from sleeping, and scorn from the public over the disaster.

dead in his bedroom of a gunshot wound to the head. He had tendered his resignation to the Board of Directors the previous Monday. Collins was believed to have committed suicide out of grief and feeling partially responsible for the tragic accident, however, a police report at the time suggested the wound had not been self inflicted. Documents discovered in 2001 and an examination of Collins’ skull suggest that he had indeed been murdered. Amasa Stone committed suicide seven years later after experiencing financial difficulties with some foundries he had interests in, suffering from severe ulcers that kept him from sleeping, and scorn from the public over the disaster.