collision

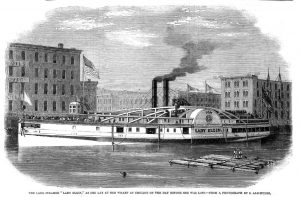

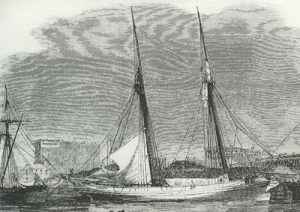

Just before midnight on September 7, 1860, a palatial sidewheel steamboat named the Lady Elgin left Chicago bound for Milwaukee. She was carrying about 400 passengers. She was returning to Milwaukee from a day-long outing to Chicago. Also on the water that night was the Augusta, a schooner filled with lumber. The captain of the Lady Elgin took notice of the Augusta around 2:30am. The night was stormy, and visibility was poor. Storm clouds raged and the waves were intense.

Just before midnight on September 7, 1860, a palatial sidewheel steamboat named the Lady Elgin left Chicago bound for Milwaukee. She was carrying about 400 passengers. She was returning to Milwaukee from a day-long outing to Chicago. Also on the water that night was the Augusta, a schooner filled with lumber. The captain of the Lady Elgin took notice of the Augusta around 2:30am. The night was stormy, and visibility was poor. Storm clouds raged and the waves were intense.

Suddenly, the lumber on the Augusta shifted, causing the two ships to collide. Instantly, the party atmosphere that had been on the Lady Elgin, turned to chaos and confusion. The Augusta received only minor damage in the collision, and kept right on sailing to Chicago. It wasn’t an unusual occurrence in those days. It’s possible that the Augusta assumed that if it wasn’t badly hurt, that larger ship probably wasn’t either. I can’t say for sure, but I know that this collision, in which the Augusta did not stop is not the first I have heard of such an incident in Maritime history. A large hole in the side of the Lady Elgin doomed the ship, which sank within thirty minutes. Only three lifeboats were able to be loaded and set into the water. The ships large upper hurricane deck fell straight into the water and served as a raft for some forty people.

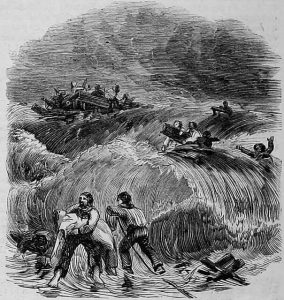

The ship had crashed two to three miles off the shore of Highland Park, but the waves were so strong that survivors, bodies, and debris were all swept down to the northern shore of Winnetka. In those days, the lakeshore in this area consisted of a narrow strip of beach rising up to clay cliffs almost 50 feet high. An angry line of breakers churned up from the storm were crashing ashore. Around 6:30am the first of the three lifeboats made it to shore in the vicinity of the Jared Gage house…which still stands at 1175 Whitebridge Hill Road. A desperate call for assistance went out to the town from the Gage house. The people of Winnetka rode  horses down to Northwestern University and the Garrett Biblical Institute to find any young men to help pull out survivors. The regional newspapers were quickly informed by telegraph. The newly completed Chicago and Milwaukee train line brought people to Winnetka to help as word of the accident spread. The effort to save the people on the Lady Elgin would have been a phenomenal feat today, but it was carried out in 1860, making it even more amazing.

horses down to Northwestern University and the Garrett Biblical Institute to find any young men to help pull out survivors. The regional newspapers were quickly informed by telegraph. The newly completed Chicago and Milwaukee train line brought people to Winnetka to help as word of the accident spread. The effort to save the people on the Lady Elgin would have been a phenomenal feat today, but it was carried out in 1860, making it even more amazing.

The crowds on the bluffs and beaches watched as pieces of wreckage washed up near the site of the present Winnetka water tower. By 10:00am, the bluffs were littered with people who had been strong enough to withstand the fierce storm of the previous night. Lastly came the hurricane deck with Captain Wilson and eight survivors whom the storm had thus far spared. Then, before their eyes, this storm-battered deck was dashed to pieces on an offshore sandbar and all on board were lost.

The storm left a tremendous undertow, creating the tragic situation…the exhausted victims had drifted close enough to the Winnetka shore to see it, only to be held back by the breakers. As the horrified onlookers watch, they died in full view of the people on shore, who could do nothing but watch. Men were lowered from the bluff with rope tied around their waists in attempts to pull people in to safety. One Evanston seminary student, Edward Spencer, is credited with saving 18 lives. Spencer is said to have repeatedly rushed into the sea, being battered by debris in order to save more people. I do not know, but I suspect that he is some relation to me on my Spencer side, and I feel honored that he was such a heroic figure. Spencer is said to have wondered many times in the aftermath, “Did I do my best?” It is the mark of a hero, never to feel like they did enough. Another man, Joseph Conrad, was said to have pulled 28 to safety. Other unknown rescuers pulled in survivors up and  down the Winnetka and North Shore coastline.

down the Winnetka and North Shore coastline.

The Gage house, the Artemas Carter house at 515 Sheridan Road, and other Winnetka residences served as temporary hospitals. The newly-built Winnetka train depot served as a morgue. Winnetka residents brought food and clothing for the survivors. It is estimated that 302 people lost their lives that day, the exact number is unknown, as the ships manifest went down with the ship. The 1860 census shows only 130 residents in the town of Winnetka. The tragedy captured the nation’s attention, but was quickly overshadowed by the 1860 elections and the Civil War. Such is the way of things. An tragic event is only well remembered, until another comes to take its place.

When most of us think of outer space, we think of a place that is quiet and still, like floating through a vacuum. I suppose that some of that is true, but while things do float around in space, they can also crash into other things floating in space. I don’t know if collisions in space make a sound, but I suspect they do. I don’t know how two objects can collide quietly, but maybe the sound does occur, and then doesn’t carry. Whether there is a sound or not, those space collisions are not soft hits, and damage can occur.

When most of us think of outer space, we think of a place that is quiet and still, like floating through a vacuum. I suppose that some of that is true, but while things do float around in space, they can also crash into other things floating in space. I don’t know if collisions in space make a sound, but I suspect they do. I don’t know how two objects can collide quietly, but maybe the sound does occur, and then doesn’t carry. Whether there is a sound or not, those space collisions are not soft hits, and damage can occur.

After NASA first put the Hubble telescope in orbit in 1990, scientists realized that the telescope’s primary mirror had a flaw called spherical aberration. Basically, the outer edge of the mirror was ground too flat by a depth of 2.2 microns. That is about as thick as one-fiftieth the thickness of a human hair. I don’t know how that could make much difference, but this aberration resulted in images that were fuzzy because some of the light from the objects being studied was being scattered. While this was not caused by other objects in space, it had to be repaired anyway. The Corrective Optics Space Telescope Axial Replacement, or COSTAR, was developed as an effective means of countering the effects of the flawed shape of the mirror. COSTAR was a telephone booth sized instrument which placed 5 pairs of corrective mirrors, some as small as a nickel coin, in front of the Faint Object Camera, the Faint Object Spectrograph and the Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph. The fix worked, and while this was not the only repair job done on the Hubble Telescope, it was the first.

NASA arranged a repair mission SM1, or Shuttle Mission: STS-61 to make the repair. The mission took place on  December 2-13, 1993 in the Shuttle Endeavor. The mission, however, was not just to fix a flaw in the original design, which would have been logical when we think of how much we depend on the Hubble Telescope, but the crew also installed and replaced other components including: Solar Arrays, Solar Array Drive Electronics (SADE), Magnetometers, Coprocessors for the flight computer, Two Rate Sensor Units, Two Gyroscope Electronic Control Units, and a GHRS Redundancy Kit. The crew included Commander Richard O. Covey, Pilot Kenneth D. Bowersox, Payload Commander F. Story Musgrave and Mission Specialists Kathryn C. Thornton, Claude Nicollier, Jeffrey A. Hoffman and Tom Akers. The mission successfully made the repairs to Hubble.

December 2-13, 1993 in the Shuttle Endeavor. The mission, however, was not just to fix a flaw in the original design, which would have been logical when we think of how much we depend on the Hubble Telescope, but the crew also installed and replaced other components including: Solar Arrays, Solar Array Drive Electronics (SADE), Magnetometers, Coprocessors for the flight computer, Two Rate Sensor Units, Two Gyroscope Electronic Control Units, and a GHRS Redundancy Kit. The crew included Commander Richard O. Covey, Pilot Kenneth D. Bowersox, Payload Commander F. Story Musgrave and Mission Specialists Kathryn C. Thornton, Claude Nicollier, Jeffrey A. Hoffman and Tom Akers. The mission successfully made the repairs to Hubble.

The Gallipoli campaign took place between April 1915 and December 1915 in an effort to take the Dardanelles from the Turkish Ottoman Empire…an ally of Germany and Austria, and thus force it out of the war. About 60,000 Australians and 18,000 New Zealanders were part of a larger British force. Among the wounded were some 26,000 Australians and 7,571 New Zealanders, while 7,594 Australians and 2,431 New Zealanders were killed. Numerically, Gallipoli was a minor campaign, but it took on considerable national and personal importance to the Australians and New Zealanders who fought there.

The Gallipoli campaign took place between April 1915 and December 1915 in an effort to take the Dardanelles from the Turkish Ottoman Empire…an ally of Germany and Austria, and thus force it out of the war. About 60,000 Australians and 18,000 New Zealanders were part of a larger British force. Among the wounded were some 26,000 Australians and 7,571 New Zealanders, while 7,594 Australians and 2,431 New Zealanders were killed. Numerically, Gallipoli was a minor campaign, but it took on considerable national and personal importance to the Australians and New Zealanders who fought there.

The Gallipoli Campaign was Australia’s and New Zealand’s introduction to the Great War. Many Australians and New Zealanders fought on the Peninsula from the day of the landings (April 25, 1915) until the evacuation on December 20, 1915. The 25th April is the New Zealand equivalent of Armistice Day and is marked as the ANZAC day in both countries with Dawn Parades and  other services in every city and town. Shops are closed in the morning. It is a very important day to Australians and New Zealanders for a variety of reasons that have changed and transmuted over the years. This campaign, while small in losses, was huge in the hearts of the Australians and New Zealanders.

other services in every city and town. Shops are closed in the morning. It is a very important day to Australians and New Zealanders for a variety of reasons that have changed and transmuted over the years. This campaign, while small in losses, was huge in the hearts of the Australians and New Zealanders.

While many losses came out of this campaign, it seems that there were two who were saved…potentially anyway. After the campaign was over, and people were wandering the area, someone came across an unusual, and seriously rare, find. There on the ground were two bullets that had collided with each other in mid-air, thus saving the lives of the two combatants who fired the rounds. Obviously, they could have been hit by another round, in which case the mid-air collision only slightly prolonged their lives. At least this scenario might be what you would think. The reality is that you would be wrong. Taking a look closer at the bullets, it is quite obvious that one round collided with  another. But the round on the left doesn’t have any rifling on it, whereas the round on the right does. They collided, but in reality, the round on the left probably wasn’t moving as fast as an actual speeding bullet. Maybe it was part of a clip on an ANZAC soldiers webgear as he was in an attack, or some other bizarre reason. But this most certainly wasn’t the intersection of two trajectories between the lines…making such a collision between two bullets even more rare. Nevertheless, the picture itself is quite interesting, and would have caught the eye of anyone looking at it. How they got there really makes no difference, but the fact that they were found on the Gallipoli battlefield makes them an interesting find. If you ask me, it is still a very rare occurrence.

another. But the round on the left doesn’t have any rifling on it, whereas the round on the right does. They collided, but in reality, the round on the left probably wasn’t moving as fast as an actual speeding bullet. Maybe it was part of a clip on an ANZAC soldiers webgear as he was in an attack, or some other bizarre reason. But this most certainly wasn’t the intersection of two trajectories between the lines…making such a collision between two bullets even more rare. Nevertheless, the picture itself is quite interesting, and would have caught the eye of anyone looking at it. How they got there really makes no difference, but the fact that they were found on the Gallipoli battlefield makes them an interesting find. If you ask me, it is still a very rare occurrence.

Anytime a group of people goes on strike, there are side effects that go beyond the management having to do more work. One of the industries in which a strike can have devastating side effects is the airline industry. When air traffic controllers strike, and the people filling in for them are not used to doing that job, even if they are trained, things can get out of hand quickly. They are likely understaffed, and stressed, but you can’t let these planes fly without guidance, so you use people in management, who probably haven’t done this work in a long time. Such was the case on March 5, 1973, over France when two Spanish aircraft, a DC9 and a Coronado 990 collided 27,000 feet above Nantes, in western France.

Anytime a group of people goes on strike, there are side effects that go beyond the management having to do more work. One of the industries in which a strike can have devastating side effects is the airline industry. When air traffic controllers strike, and the people filling in for them are not used to doing that job, even if they are trained, things can get out of hand quickly. They are likely understaffed, and stressed, but you can’t let these planes fly without guidance, so you use people in management, who probably haven’t done this work in a long time. Such was the case on March 5, 1973, over France when two Spanish aircraft, a DC9 and a Coronado 990 collided 27,000 feet above Nantes, in western France.

Sixty eight people were killed when the two Spanish aircraft collided in mid-air over France that morning,  where air traffic controllers are on strike. The dead, who included a two year old child and 47 Britons, were on board a Spanish Airlines DC9 from Palma, Majorca to London. Eye witnesses said that the DC9 exploded and broke up in mid-air following the collision. Max Chevalier, British Honorary vice-consul at Nantes, said, “Suddenly a streak of red light appeared and part of the aircraft came down with bodies flying out. It was a horrible sight.”

where air traffic controllers are on strike. The dead, who included a two year old child and 47 Britons, were on board a Spanish Airlines DC9 from Palma, Majorca to London. Eye witnesses said that the DC9 exploded and broke up in mid-air following the collision. Max Chevalier, British Honorary vice-consul at Nantes, said, “Suddenly a streak of red light appeared and part of the aircraft came down with bodies flying out. It was a horrible sight.”

The pilot of the Coronado 990, Captain Antonio Arenas-Rodriguez, was able to land his damaged aircraft safely at a military airfield in Cognac. All 108 people on board survived without injury. A passenger on board the Coronado aircraft, Leonard Wareham, 59, who lives in Madrid, said, “We were sitting on the port side of the aircraft. My wife had the window seat. There was an enormous bump and then everything seemed to fall about. No-one knew what was happening except that the aircraft was falling fast. The next thing I  noticed was that a French fighter plane was flying around us and evidently he guided us in to land.”

noticed was that a French fighter plane was flying around us and evidently he guided us in to land.”

At least 16 airlines, including British European Airlines (BEA) and Caledonian, cancelled flights over France following news of the accident. Members of the French Civilian Air Controllers Association (SNCTA), have been on strike illegally since February 20, 1973 hoping to gain improved pension benefits and obtain the right to strike which was outlawed for air traffic controllers in 1964. Military air traffic controllers were put in place to operate France’s air control system on February 26.

On a clear night, ocean travel is really safe, because ships can see each other easily. Fog, however, presents a much different situation. Nevertheless, radar should solve any problem that fog can cause…right? Theoretically, yes, it should, but on the night of July 25, 1856, something went horribly wrong with that whole system, and the authorities were very puzzled as to the cause. At 11:00pm on that Wednesday night, 45 miles south of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts…with a heavy Atlantic fog hanging in the air, two ships carrying 2,453 people were just ten minutes from disaster.

On a clear night, ocean travel is really safe, because ships can see each other easily. Fog, however, presents a much different situation. Nevertheless, radar should solve any problem that fog can cause…right? Theoretically, yes, it should, but on the night of July 25, 1856, something went horribly wrong with that whole system, and the authorities were very puzzled as to the cause. At 11:00pm on that Wednesday night, 45 miles south of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts…with a heavy Atlantic fog hanging in the air, two ships carrying 2,453 people were just ten minutes from disaster.

In the mid-1950s, travel by steamer between Europe and America was commonplace. More than 50 passenger liners regularly made the transatlantic ocean voyage. The Andrea Doria was one of the most lavishly adorned steamers. Put to sea in 1953, it was the pride of the Italian line. It was built for luxury, not speed, and boasted extensive safety precautions, such as state-of-the-art radar systems and 11 watertight compartments in its hull. The Swedish ocean liner Stockholm, went into service in 1948. It was a more modest ocean liner, less than half the tonnage and carrying 747 passengers and crew on that fateful night. The Andrea Doria, by contrast carried 1,706 passengers and crew that night.

On the night of July 25, 1956, the Stockholm was beginning its journey home to Sweden from New York, while the Andrea Doria was steaming toward New York. The Andrea Doria had been in an intermittent fog since midafternoon, but Captain Piero Calami, relying on his ship’s radar to get him to his destination safely and on schedule, only slightly reduced his speed. At the same time, the Stockholm was directed north of its recommended route by Captain H. Gunnar Nordenson, who was trying to reduce his travel time. In so doing, he risked encountering westbound vessels. The Stockholm also had radar and expected no difficulty in navigating past approaching vessels. Captain Nordenson failed to anticipate that a ship like the Andrea Doria could be hidden until the last few minutes by a fogbank.

At 10:45pm, the Stockholm showed up on the Andrea Doria’s radar screens, about 17 nautical miles away. Soon after, the Andrea Doria showed up on the Stockholm’s radar, about 12 miles away. What happened next has been disputed, but it’s likely that the crews of both ships misread their radar sets. Captain Calami made a dangerous decision to turn the Andrea Doria to port for an unconventional starboard-to-starboard passing, which he erroneously thought the Stockholm was attempting. About two miles away from each other, the ship’s lights came into view of each other. Third Officer Johan-Ernst Bogislaus Carstens, commanding the bridge of the Stockholm, then made a conventional turn to starboard. Less than a mile away, Captain Calami realized he was on a collision course with the Stockholm and turned hard to the left, hoping to race past the bow of the Stockholm. Both ships were too large and moving too fast to make a quick turn. At 11:10pm, the Stockholm‘s sharply angled bow, reinforced for breaking ice, smashed 30 feet into the starboard side of the Andrea Doria. For a moment, the smaller ship was lodged there like a cork in a bottle. Then, the opposite momentum of the two ships pulled them apart, and the Stockholm‘s smashed bow screeched down the side of the Doria, sending sparks into the air.

Five crewmen of the Stockholm were killed in the collision. The Andrea Doria fared far worse. The bow of the Stockholm crashed through passenger cabins, and 46 passengers and crew were killed. One man watched as his wife was dragged away forever by the retreating bow of the Stockholm. Fourteen year old Linda Morgan was asleep on the Andrea Doria when the impact somehow threw her out of bed and onto the Stockholm’s crushed bow. She was later dubbed “the miracle girl” by the press. With seven of its 10 decks ripped open and exposed to the Atlantic waters, the Andrea Doria listed more than 20 degrees to port in minutes, and its watertight compartments were compromised. A lifeboat evacuation began on the doomed ship, but went far from smoothly. The port side could not be used because the ship was listing too much, which left lifeboat seats for 1,044 of the 1,706 people on board. Passengers in the lower cabins fought their way through darkened hallways quickly filling with ocean water and leaking oil. The first lifeboat was finally deployed an hour after the collision, and held more crew than passengers. Because the Stockholm had suffered a nonfatal  blow, it was able to lend its lifeboats to the evacuation effort. Several ships heard the Doria’s mayday and came to assist. At 2:00am on July 26, the Ile de France, another great ocean liner, arrived and took charge of the rescue effort. It was the greatest civilian maritime rescue in history, and 1,660 lives were saved. The Stockholm limped back to New York, damaged but afloat. At 10:09am on July 26, the Andrea Doria sank into the Atlantic. Almost immediately, the wreck, which is located at a depth of 240 feet of water, became a popular scuba diving destination. However, the Andrea Doria is known as the “Mount Everest” of diving locations, because of the extreme depth, the presence of sharks, and unpredictable currents.

blow, it was able to lend its lifeboats to the evacuation effort. Several ships heard the Doria’s mayday and came to assist. At 2:00am on July 26, the Ile de France, another great ocean liner, arrived and took charge of the rescue effort. It was the greatest civilian maritime rescue in history, and 1,660 lives were saved. The Stockholm limped back to New York, damaged but afloat. At 10:09am on July 26, the Andrea Doria sank into the Atlantic. Almost immediately, the wreck, which is located at a depth of 240 feet of water, became a popular scuba diving destination. However, the Andrea Doria is known as the “Mount Everest” of diving locations, because of the extreme depth, the presence of sharks, and unpredictable currents.