british

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

Most people think that English came from England, and of course, it did, however, in England prior to the 19th century, the English language was not spoken by the aristocracy, but rather only by “commoners.” Back then, English used to belong to the people, and I suppose that might explain some of the “incorrect” uses of the language which have been so severely attacked by contemporary English speakers. Prior to the 19th century, the aristocracy in English courts spoke French. This was due to the Norman Invasion of 1066 and caused years of division between the “gentlemen” who had adopted the Anglo-Norman French and those who only spoke English. Even the famed King Richard the Lionheart was actually primarily referred to in French, as Richard “Coeur de Lion.”

In my opinion, this dual language society would have caused numerous problems. The indication I get is that neither side could speak the language of the other, but I don’t know how a monarchy could rule, if the “commoners” could not understand the language and therefore the orders of the monarchy. French was spoken and learned by anyone in the upper  classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

classes. However, it became less useful as English lost its control of various places in France, where the peasants spoke French, too. After that…about, 1450…English was simply more useful for talking to anybody. It is still true that British royals and many nobles are fluent in French, but they only use it to talk to French people, just like everybody else.

To further confuse your preconceptions about the English language, the “British accent” was, in reality, created after the Revolutionary War, meaning contemporary Americans sound more like the colonists and British soldiers of the 18th century than contemporary Brits. Many people have made a point of how much they love the British accent, but I think very few people know the real story behind the British accent. In the 18th century and before, the British “accent” was the way we speak herein America. Of course, accents vary greatly  by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

by region, as we have seen with the accents of the south and east in the United States, but the “BBC English” or public school English accent…which sounds like the James Bond movies…didn’t come about until the 19th century and was originally adopted by people who wanted to sound fancier. I suppose it was like the aristocracy and the commoners, in that one group didn’t want to be mistaken for the other. After being handily defeated by the American colonists, I’m sure that the British were looking for a way to seem superior, even in defeat. The change in the accent of the English language was sufficient to make that distinction. Maybe it was their way of saying that they were better than the American guerilla-type soldiers who beat them in combat…basically they might have lost, but they were superior…even if it was only in how they sounded.

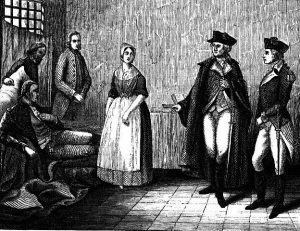

How many Generals can say that a housewife saved their life? Not many, I’m sure. Most housewives would never get near enough to a general in combat to do anything, but in the 1700s, things were different. Of course, it wasn’t like Philadelphia housewife and nurse Lydia Darragh, got out there and fought along-side General Washington and his Continental Army, but she was, nevertheless, able to single-handedly save their lives when she overheard the British planning a surprise attack on Washington’s army for the following day. Some say this is just a legend, and I guess we will never know for sure, but the story has endured for 240 years, which says something to me.

How many Generals can say that a housewife saved their life? Not many, I’m sure. Most housewives would never get near enough to a general in combat to do anything, but in the 1700s, things were different. Of course, it wasn’t like Philadelphia housewife and nurse Lydia Darragh, got out there and fought along-side General Washington and his Continental Army, but she was, nevertheless, able to single-handedly save their lives when she overheard the British planning a surprise attack on Washington’s army for the following day. Some say this is just a legend, and I guess we will never know for sure, but the story has endured for 240 years, which says something to me.

This historic event happened on December 2, 1777, during the occupation of Philadelphia. British General William Howe had stationed his headquarters across the street from the Darragh home. When Howe’s headquarters proved too small to hold meetings, he commandeered a large upstairs room in the Darraghs’ house. Although uncorroborated, family legend holds that Mrs. Darragh used to eavesdrop and take notes on the British meetings from an adjoining room and would conceal the notes by sewing them into her coat before passing them onto American troops stationed outside the city. It was a critical mistake on the part of the British, and the ingenious way of passing the information worked very well for the patriots.

On the evening of December 2, 1777, Darragh overheard the British commanders planning a surprise attack on Washington’s army at Whitemarsh, Pennsylvania, for December 4th and 5th. Somehow, it completely amazes me that they would be so careless with the information, especially considering the fact that they were in the home of the enemy. I guess they assumed that the housewife would have no idea what the “great military minds” were thinking or talking about, nor that she would have any way to pass the information to anyone who could do anything about it. I’m sure they were completely shocked when they realized that she had tipped General Washington off to the plot, and saved the lies of him and his army…as well as saving the day.

Using a cover story that she needed to buy flour from a nearby mill just outside the British line, Darragh passed the information to American Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Craig the following day. The British marched towards Whitemarsh on the evening of December 4, 1777, and were surprised to find General Washington and

the Continental Army waiting for them. After three inconclusive days of skirmishing, General Howe chose to return his troops to Philadelphia. It’s an amazing victory for General Washington and his Continental Army, and it all happened because a patriot housewife turned spy for her country. When you think about it, she already had the perfect disguise for the job. It is said that members of the Central Intelligence Agency still tell the story of one of the first spies in American history.

the Continental Army waiting for them. After three inconclusive days of skirmishing, General Howe chose to return his troops to Philadelphia. It’s an amazing victory for General Washington and his Continental Army, and it all happened because a patriot housewife turned spy for her country. When you think about it, she already had the perfect disguise for the job. It is said that members of the Central Intelligence Agency still tell the story of one of the first spies in American history.

Sometimes, when a war plane is in danger of being captured by the enemy, the pilot might take measures to destroy it, so that the technological secrets don’t end up in enemy hands. In fact, I believe that these days, anytime a plane goes down in enemy territory, the pilots are told to destroy them, but I’m not sure on that.

Sometimes, when a war plane is in danger of being captured by the enemy, the pilot might take measures to destroy it, so that the technological secrets don’t end up in enemy hands. In fact, I believe that these days, anytime a plane goes down in enemy territory, the pilots are told to destroy them, but I’m not sure on that.

Strange as that may seem to most of us, on November 27, 1942, something even more strange happened, but I’m getting ahead of myself. In June of 1940, after the German invasion of France and the establishment of an unoccupied zone in the southeast, which was led by General Philippe Petain, Admiral Jean Darlan was committed to keeping the French fleet out of German control. At the same time, as a minister in the government that had signed an armistice with the Germans, one that promised a relative “autonomy” to Vichy France, Darlan was prohibited from sailing that fleet to British or neutral waters. It put him in a rather precarious position, to say the least.

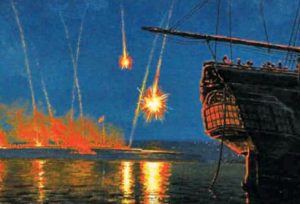

The British were as concerned as the French. A German-commandeered fleet in southern France, so close to British-controlled regions in North Africa, could prove disastrous to the British, who decided to take matters into their own hands by launching Operation Catapult…the attempt by a British naval force to persuade the French naval commander at Oran to either break the armistice and sail the French fleet out of the Germans’ grasp…or to scuttle it. And if the French wouldn’t, the Brits would. If you’ve ever heard the expression, “between a rock and a hard place,” you can picture this situation. And the British tried to push their way in it. In a five-minute missile bombardment, they managed to sink one French cruiser and two old battleships. They also killed 1,250 French sailors. This would be the source of much bad blood between France and England throughout the war. General Petain broke off diplomatic relations with Great Britain.

Two years later, the situation had worsened, with the Germans now in Vichy and the armistice already violated. Admiral Jean de Laborde finished the job the British had started. Just as the Germans launched Operation Lila…

the attempt to commandeer the French fleet, at Toulon harbor, off the southern coast of France, Laborde ordered the sinking of 2 battle cruisers, 4 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, 1 aircraft transport, 30 destroyers, and 16 submarines. Three French subs managed to escape the Germans and make it to Algiers, Allied territory. Only one sub fell into German hands. The marine equivalent of a scorched-earth policy had succeeded.

the attempt to commandeer the French fleet, at Toulon harbor, off the southern coast of France, Laborde ordered the sinking of 2 battle cruisers, 4 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, 1 aircraft transport, 30 destroyers, and 16 submarines. Three French subs managed to escape the Germans and make it to Algiers, Allied territory. Only one sub fell into German hands. The marine equivalent of a scorched-earth policy had succeeded.

These days, everyone has heard of the special forces units and special ops, which is special operations. The main reasons we know about them are terrorism, and war in the current world. Special forces and special operations forces are military units trained to conduct the kinds of operations that are often much more dangerous than even the boots on the ground part of battle. NATO defines special operations as “military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, trained, and equipped forces, manned with selected personnel, using unconventional tactics, techniques, and modes of employment”. In other words, these are the guys who go into ugly situations in an effort to keep us safe. Of course, this, in no way, detracts from our first responders, who we all know are just as vital. There is just a difference in the scope of their jobs. The Special Forces emerged in the early 20th century, with a significant growth in the field during the World War II, when “every major army involved in the fighting” created formations devoted to special operations behind enemy lines. It was going to be the only way to win such a war.

These days, everyone has heard of the special forces units and special ops, which is special operations. The main reasons we know about them are terrorism, and war in the current world. Special forces and special operations forces are military units trained to conduct the kinds of operations that are often much more dangerous than even the boots on the ground part of battle. NATO defines special operations as “military activities conducted by specially designated, organized, trained, and equipped forces, manned with selected personnel, using unconventional tactics, techniques, and modes of employment”. In other words, these are the guys who go into ugly situations in an effort to keep us safe. Of course, this, in no way, detracts from our first responders, who we all know are just as vital. There is just a difference in the scope of their jobs. The Special Forces emerged in the early 20th century, with a significant growth in the field during the World War II, when “every major army involved in the fighting” created formations devoted to special operations behind enemy lines. It was going to be the only way to win such a war.

Special Forces teams perform some dangerous functions, including airborne operations, counter-insurgency, counter-terrorism, foreign internal defense, covert ops, direct action, hostage rescue, high-value targets/manhunting, intelligence operations, mobility operations, and unconventional warfare. In the United States, Special Forces refers to the US Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine forces. The jobs of the Special Forces units are vital in today’s kind of warfare. Special Forces do reconnaissance and surveillance in hostile environments trying to make it safer to send in the troops. They are in charge of foreign internal defense…training and development of other states’ military and security forces, offensive action, support to counter-insurgency through population engagement and support counter-terrorism operations, sabotage, and demolition, as well as, hostage rescue. They are also used as body guards, in waterborne operations involving combat diving, combat swimming, maritime boarding and amphibious missions, as well as support of air force operations. Special forces have played an important role throughout the history of warfare, whenever the aim was to achieve disruption by “hit and run” and sabotage, rather than more traditional conventional combat. Other significant roles lay in reconnaissance, providing essential intelligence from near or among the enemy and increasingly in combating irregular forces, their infrastructure, and their activities. Originally there were separate units for the different branches of the military, but the need for interoperability between these units from the different services led to the formation US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) in 1987. Our cousin Paul Noyes career in Special Operations was with Ranger, Special Forces and Aviation Special Ops forces, and he has become my military “go to” guy…letting me know if I hit the nail on the head or missed it.

For some reason, I thought Special Forces was, for the most part, a modern day unit, but that isn’t really true. Chinese strategist Jiang Ziya, in his Six Secret Teachings, described recruiting talented and motivated men into specialized elite units with functions such as commanding heights and making rapid long-distance advances. King David had a special forces platoon known as Gibborim. In Japan, ninjas were used for reconnaissance, espionage and as assassins, bodyguards or fortress guards, or otherwise fought alongside conventional soldiers. During the Napoleonic wars, rifle and sapper units were formed that held specialized roles in reconnaissance and skirmishing and were not committed to the formal battle lines. The British Indian Army

deployed two special forces during their border wars…the Corps of Guides formed in 1846 and the Gurkha Scouts…a force that was formed in the 1890s and was first used as a detached unit during the 1897–1898 Tirah Campaign. I guess that the Special Forces units are long standing, expertly trained groups of very special people, who have achieved a level of expertise that is second to none, and I for one, and thankful that such soldiers exist.

deployed two special forces during their border wars…the Corps of Guides formed in 1846 and the Gurkha Scouts…a force that was formed in the 1890s and was first used as a detached unit during the 1897–1898 Tirah Campaign. I guess that the Special Forces units are long standing, expertly trained groups of very special people, who have achieved a level of expertise that is second to none, and I for one, and thankful that such soldiers exist.

Most people know what the United States Capitol building looks like, and many have seen it, and even been inside it, but I wonder how many people know that is almost wasn’t completed. Yes, you heard me right. I almost wasn’t completed. As a young nation, the United States had no permanent capitol, and Congress met in eight different cities, including Baltimore, New York and Philadelphia, before 1791. In 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which gave President Washington the power to select a permanent home for the federal government. The following year, he chose what would become the District of Columbia from land that had been provided by Maryland. Washington picked three commissioners to oversee the capital city’s development and they in turn chose French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant to come up with the design. However, L’Enfant clashed with the commissioners and was fired in 1792. A design competition was held, and a Scotsman named William Thornton submitted the winning entry.

Most people know what the United States Capitol building looks like, and many have seen it, and even been inside it, but I wonder how many people know that is almost wasn’t completed. Yes, you heard me right. I almost wasn’t completed. As a young nation, the United States had no permanent capitol, and Congress met in eight different cities, including Baltimore, New York and Philadelphia, before 1791. In 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which gave President Washington the power to select a permanent home for the federal government. The following year, he chose what would become the District of Columbia from land that had been provided by Maryland. Washington picked three commissioners to oversee the capital city’s development and they in turn chose French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant to come up with the design. However, L’Enfant clashed with the commissioners and was fired in 1792. A design competition was held, and a Scotsman named William Thornton submitted the winning entry.

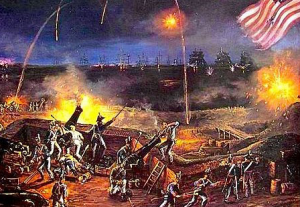

Then, on this day, September 18, 1793, Washington laid the Capitol’s cornerstone and the lengthy construction process, which would involve a line of project managers and architects, got under way. One would think that is due time, the capitol building would be finished, but in reality, it took almost a century to finish…almost 100 years!! During those years, architects came and went, the British set it on fire, and it was called into use during the Civil War. In 1800, Congress moved into the Capitol’s north wing. In 1807, the House of Representatives moved into the building’s south wing, which was finally finished in 1811. During the War of 1812, the British invaded Washington DC. They set fire to the Capitol on August 24, 1814. Thankfully, a rainstorm saved the building from total destruction. Congress met in nearby temporary quarters from 1815 to 1819. In the early 1850s, work began to expand the Capitol to accommodate the growing number of Congressmen. The Civil War halted construction in 1861 while the Capitol was used by Union troops as a hospital and barracks. Following the war, expansions and modern upgrades to the building continued into the next century.

Today, the Capitol building, with its famous cast-iron dome and important collection of American art, is part of the Capitol Complex, which includes six Congressional office buildings and three Library of Congress buildings, all developed in the 19th and 20th centuries. The Capitol, which is visited by 3 million to 5 million people each

year, has 540 rooms and covers a ground area of about four acres. I’m sure that those who visit the United States Capitol Building probably hear all about it strange past and its construction history, but maybe not. I suppose that it depends on what the tour guide finds interesting. Personally, I like the unusual construction. Thankfully, the United States Capitol did finally get built and has become the beautiful building we know today.

year, has 540 rooms and covers a ground area of about four acres. I’m sure that those who visit the United States Capitol Building probably hear all about it strange past and its construction history, but maybe not. I suppose that it depends on what the tour guide finds interesting. Personally, I like the unusual construction. Thankfully, the United States Capitol did finally get built and has become the beautiful building we know today.

When I think of Independence Day, I often think about how the fireworks remind me of the many battles that went on in order to win our freedom. Then, I began to wonder if there was ever a time when the 13 colonies almost didn’t become the United States. Britain was, after all, the world’s greatest superpower at the time. British soldiers fought on 5 continents and they had an amazing navy. They massacred rebels and civilians in Jamaica and India around the same time and retained those colonies. So, why not the 13 colonies of North America? There are many explanations, but the one I found most interesting seems, almost to tie to the way things are in America right now…and really all along.

When I think of Independence Day, I often think about how the fireworks remind me of the many battles that went on in order to win our freedom. Then, I began to wonder if there was ever a time when the 13 colonies almost didn’t become the United States. Britain was, after all, the world’s greatest superpower at the time. British soldiers fought on 5 continents and they had an amazing navy. They massacred rebels and civilians in Jamaica and India around the same time and retained those colonies. So, why not the 13 colonies of North America? There are many explanations, but the one I found most interesting seems, almost to tie to the way things are in America right now…and really all along.

The reality is that Britain won many times on the battlefield, but…lost in the taverns. The taverns, you say. How  could that be? Well, taverns were everywhere. They were the social network of colonial life, much like the town hall meetings, and even more, like Facebook or Twitter today. Some areas of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had taverns every few miles. People could get their mail there, hire a worker, talk to friends, sell crops, buy land, and eat a good meal. It was in these places that opinions were formed. People discussed the problems they had with British rule, and talked about how to get rid of the yoke of the Mother country.

could that be? Well, taverns were everywhere. They were the social network of colonial life, much like the town hall meetings, and even more, like Facebook or Twitter today. Some areas of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had taverns every few miles. People could get their mail there, hire a worker, talk to friends, sell crops, buy land, and eat a good meal. It was in these places that opinions were formed. People discussed the problems they had with British rule, and talked about how to get rid of the yoke of the Mother country.

Some say that Britain might have had a chance if they had been represented in the taverns too, but I don’t think so. The time had come for Americans to think for themselves, and to run their own lives and their own country. First came the Stamp Act and the Americans protested. More oppression followed, as did the protests.  The resistance grew and grew, until war broke out. No matter what it took, the colonies were determined not to lose. The tavern meetings had accomplished what they needed to. No matter how many times it looked like Britain might win, they would not, because of…well, social networking. Social networking, when people get together to discuss right from wrong, and to discuss solutions. Sometimes the solutions are simple, and other times they create enough of a stir to bring about a revolution. No matter what the reason, the colonies were not about to lose, and because of that, we are a free nation and it was on this day, July 4, 1776 that our independence was made a reality, and we became the land of the free and the home of the brave. Happy Independence Day America!!

The resistance grew and grew, until war broke out. No matter what it took, the colonies were determined not to lose. The tavern meetings had accomplished what they needed to. No matter how many times it looked like Britain might win, they would not, because of…well, social networking. Social networking, when people get together to discuss right from wrong, and to discuss solutions. Sometimes the solutions are simple, and other times they create enough of a stir to bring about a revolution. No matter what the reason, the colonies were not about to lose, and because of that, we are a free nation and it was on this day, July 4, 1776 that our independence was made a reality, and we became the land of the free and the home of the brave. Happy Independence Day America!!

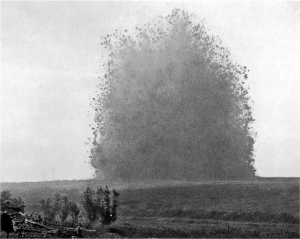

The manner in which battles are fought and won, never ceases to amaze me. In 1916, British forces began planning the Battle of Messines Ridge. For 18 months, soldiers worked to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the Germans had long since been entrenched. The Germans had no idea that they were there, and no idea what was going to happen. I find myself in complete amazement, that all those soldiers were working a mere 100 feet below ground, and the German soldiers above them had no idea. It was the element of surprise that was the whole key to this successful attack.

The manner in which battles are fought and won, never ceases to amaze me. In 1916, British forces began planning the Battle of Messines Ridge. For 18 months, soldiers worked to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the Germans had long since been entrenched. The Germans had no idea that they were there, and no idea what was going to happen. I find myself in complete amazement, that all those soldiers were working a mere 100 feet below ground, and the German soldiers above them had no idea. It was the element of surprise that was the whole key to this successful attack.

At 3:10am on June 7, 1917, a series of simultaneous explosions rocked the area. The explosions were heard as far away as London. A German observer described the explosions saying, “nineteen gigantic roses with carmine petals, or enormous mushrooms, rose up slowly and majestically out of the ground and then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” While Messines Ridge itself was considered a relatively limited victory, it had a considerable effect. German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men who were too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

At 3:10am on June 7, 1917, a series of simultaneous explosions rocked the area. The explosions were heard as far away as London. A German observer described the explosions saying, “nineteen gigantic roses with carmine petals, or enormous mushrooms, rose up slowly and majestically out of the ground and then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” While Messines Ridge itself was considered a relatively limited victory, it had a considerable effect. German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men who were too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

It was a crushing victory over the Germans. The German army was forced to retreat to the east. This retreat and the sacrifice that it entailed marked the beginning of their gradual, but continuous loss of territory along the Western Front. It also secured the right flank of the British army’s push towards the much-contested Ypres region, which was the eventual objective of the planned attack. Over the next month and a half, British forces continued to push the Germans back toward the high ridge at Passchendaele. Then on July 31 the British army launched it’s offensive, known as the Battle of Passchendaele or the Third Battle of Ypres.

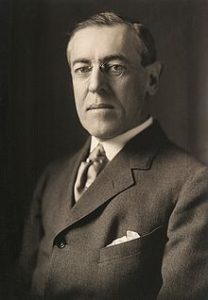

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

The non-stop German offensive continued to take its toll throughout the month of April, however, because the majority of American troops in Europe, who were now arriving at a rate of 120,000 a month, were still not sent into battle. In a meeting of the Supreme War Council of Allied leaders at Abbeville, near the coast of the English Channel, which began on May 1, 1918, Clemenceau, Lloyd George and General Ferdinand Foch, the recently named Generalissimo of all Allied forces on the Western Front, was trying hard to persuade Pershing to send all the existing American troops to the front at once. Pershing resisted, reminding the group that the United States had entered the war “independently” of the other Allies, and indeed, the United States would insist during and after the war on being known as an “associate” rather than a full-fledged ally. He further stated, “I do not suppose that the American army is to be entirely at the disposal of the French and British commands.” I’m sure his remarks brought with them, much concern.

On May 2, the second day of the meeting, the debate continued, with Pershing holding his ground in the face of  heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.

heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.

When the United States was first trying to become a sovereign nation, due to the unfair treatment it received from its parent nation, Great Britain, King George III’s army tried to stop it in any way they could. I’m sure the king could see the possibilities this nation had, and I’m also sure he could see the writing on the wall concerning our independence. Still, the king said to fight, so fight they did. The people in the colonies thought the king’s rule was tyrannical and infringed on the colonists’ “rights as Englishmen”, and so they declared the colonies were going to be free and independent states. A war ensued, that we know as the Revolutionary War.

When the United States was first trying to become a sovereign nation, due to the unfair treatment it received from its parent nation, Great Britain, King George III’s army tried to stop it in any way they could. I’m sure the king could see the possibilities this nation had, and I’m also sure he could see the writing on the wall concerning our independence. Still, the king said to fight, so fight they did. The people in the colonies thought the king’s rule was tyrannical and infringed on the colonists’ “rights as Englishmen”, and so they declared the colonies were going to be free and independent states. A war ensued, that we know as the Revolutionary War.

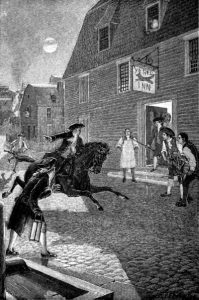

On April 7, 1775, British activity suggested the possibility of troop movements, and Dr Joseph Warren, an American physician who played a leading role in American Patriot organizations in Boston in the early days of the American Revolution, sent Paul Revere to warn the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, which was located in Concorde. This was also the site of one of the larger caches of Patriot military supplies. The warning spurred the residents into action…moving the military supplies away from the town. Just one week later, on April 14, General Gage received instructions from Secretary of State William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth. The orders had been dispatched on January 27. The British soldiers were told to disarm the rebels. It was known that they often hid weapons in Concord, as well as other locations. They were told to imprison the rebellion’s leaders, especially Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Dartmouth gave Gage considerable discretion in his commands. Gage issued orders to Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith to proceed from Boston “with utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy… all Military stores…. But you will take care that the soldiers do not plunder the inhabitants or hurt private property.” Gage did not issue written orders for the arrest of rebel leaders, because he was afraid that doing so might spark an uprising.

On the night of April 18, 1775, with tensions rising, Joseph Warren went to see Revere and William Dawes. He told them that the king’s troops were about to embark in boats from Boston bound for Cambridge, as well as the road to Lexington and Concord. Warren’s intelligence suggested that the most likely objectives of the  regulars’ movements later that night would be the capture of Adams and Hancock. They did not worry about the possibility of regulars marching to Concord, since the supplies at Concord were safe, but they did think their leaders in Lexington were unaware of the potential danger that night. Revere and Dawes were sent out to warn them and to alert colonial militias in nearby towns. Prior to this time, Revere had instructed Robert Newman, the sexton of the North Church, to send a signal by lantern to alert colonists in Charlestown as to the movements of the troops when the information became known. In what is well known today by the phrase “one if by land, two if by sea”, one lantern in the steeple would signal the army’s choice of the land route while two lanterns would signal the route “by water” across the Charles River. The British would ultimately take the water route, so two lanterns were placed in the steeple. Revere first gave instructions to send the signal to Charlestown. He then crossed the Charles River by rowboat, slipping past the British warship HMS Somerset at anchor. Crossings were banned at that hour, but Revere safely landed in Charlestown and rode to Lexington, avoiding a British patrol and later warning almost every house along the route. The Charlestown colonists dispatched additional riders to the north. Riding through present-day Somerville, Medford, and Arlington, Revere warned patriots along his route, many of whom set out on horseback to deliver warnings of their own. By the end of the night there were probably as many as 40 riders throughout Middlesex County carrying the news of the army’s advance. Revere did not shout the phrase “The British are coming!” The success of his mission depended on secrecy, and the countryside was filled with British army patrols, and most of the Massachusetts colonists, who were predominantly English loyalists. Revere’s warning, according to eyewitness accounts of the ride and Revere’s own descriptions, was “The Regulars are coming out.” Revere arrived in Lexington around midnight, with Dawes arriving about a ½ hour later. They met with Samuel Adams and John Hancock, spending a great deal of time discussing plans of action. They believed that the forces leaving the city were too large for the sole purpose of arresting two men and that Concord was the main target. The Lexington men dispatched riders to the surrounding towns, and Revere and Dawes continued along the road to Concord accompanied by Samuel Prescott, a doctor who happened to be in Lexington. Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by a British Army patrol in Lincoln at a roadblock on the way to Concord. Prescott jumped his horse over a wall and escaped into the woods. He eventually reached Concord. Dawes also escaped, but fell off his horse not long after and did not complete the ride. After being roughly questioned for an hour or two, Revere was released when the patrol heard Minutemen alarm guns being fired on their approach to Lexington.

regulars’ movements later that night would be the capture of Adams and Hancock. They did not worry about the possibility of regulars marching to Concord, since the supplies at Concord were safe, but they did think their leaders in Lexington were unaware of the potential danger that night. Revere and Dawes were sent out to warn them and to alert colonial militias in nearby towns. Prior to this time, Revere had instructed Robert Newman, the sexton of the North Church, to send a signal by lantern to alert colonists in Charlestown as to the movements of the troops when the information became known. In what is well known today by the phrase “one if by land, two if by sea”, one lantern in the steeple would signal the army’s choice of the land route while two lanterns would signal the route “by water” across the Charles River. The British would ultimately take the water route, so two lanterns were placed in the steeple. Revere first gave instructions to send the signal to Charlestown. He then crossed the Charles River by rowboat, slipping past the British warship HMS Somerset at anchor. Crossings were banned at that hour, but Revere safely landed in Charlestown and rode to Lexington, avoiding a British patrol and later warning almost every house along the route. The Charlestown colonists dispatched additional riders to the north. Riding through present-day Somerville, Medford, and Arlington, Revere warned patriots along his route, many of whom set out on horseback to deliver warnings of their own. By the end of the night there were probably as many as 40 riders throughout Middlesex County carrying the news of the army’s advance. Revere did not shout the phrase “The British are coming!” The success of his mission depended on secrecy, and the countryside was filled with British army patrols, and most of the Massachusetts colonists, who were predominantly English loyalists. Revere’s warning, according to eyewitness accounts of the ride and Revere’s own descriptions, was “The Regulars are coming out.” Revere arrived in Lexington around midnight, with Dawes arriving about a ½ hour later. They met with Samuel Adams and John Hancock, spending a great deal of time discussing plans of action. They believed that the forces leaving the city were too large for the sole purpose of arresting two men and that Concord was the main target. The Lexington men dispatched riders to the surrounding towns, and Revere and Dawes continued along the road to Concord accompanied by Samuel Prescott, a doctor who happened to be in Lexington. Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by a British Army patrol in Lincoln at a roadblock on the way to Concord. Prescott jumped his horse over a wall and escaped into the woods. He eventually reached Concord. Dawes also escaped, but fell off his horse not long after and did not complete the ride. After being roughly questioned for an hour or two, Revere was released when the patrol heard Minutemen alarm guns being fired on their approach to Lexington.

About 5am on April 19, 700 British troops under Major John Pitcairn arrived at the town to find a 77 man strong colonial militia under Captain John Parker waiting for them on Lexington’s common green. Pitcairn ordered the outnumbered Patriots to disperse, and after a moment’s hesitation, the Americans began to drift off the green. Suddenly, the “shot heard around the world” was fired from an undetermined gun, and a cloud of musket smoke soon covered the green. When the brief Battle of Lexington ended, eight Americans lay dead and 10 others were wounded Only one British soldier was injured. The American Revolution had begun.

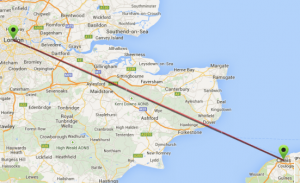

Every time I research one of the weapons used in war, I am more and more stunned by the hatred that brings the need to destroy one another. During World War II, Hitler continuously created…or rather had his scientists create newer, more powerful, and more devastating bombs. His V-1 missile, also known as the V-1 flying bomb, or in German: Vergeltungswaffe 1, meaning “Vengeance Weapon 1” became known to the Allies as the buzz bomb, or doodlebug. In Germany it was known as Kirschkern, or cherrystone, and as Maikäfer or maybug. It was an early cruise missile, and also the first production aircraft to use a pulsejet for power.

Every time I research one of the weapons used in war, I am more and more stunned by the hatred that brings the need to destroy one another. During World War II, Hitler continuously created…or rather had his scientists create newer, more powerful, and more devastating bombs. His V-1 missile, also known as the V-1 flying bomb, or in German: Vergeltungswaffe 1, meaning “Vengeance Weapon 1” became known to the Allies as the buzz bomb, or doodlebug. In Germany it was known as Kirschkern, or cherrystone, and as Maikäfer or maybug. It was an early cruise missile, and also the first production aircraft to use a pulsejet for power.

The V-1 was developed at Peenemünde Army Research Center by the Nazi German Luftwaffe during World War II. During initial development it was known by the codename “Cherry Stone.” It was first of the so-called “Vengeance weapons” (V-weapons or Vergeltungswaffen) series designed for terror bombing of London. As one of my readers, Greg (sorry, I don’t know his last name) pointed out to me, it was one of the V weapons…the V-3 to be exact that would ultimately cause the death of Joseph Kennedy, but that is a story for another day. The range of the V-1 missile was limited, and so the thousands of V-1 missiles launched into England were fired from launch facilities along the French (Pas-de-Calais) and Dutch coasts. The first V-1 was launched at London on 13 June 1944, one week after, and actually prompted by the successful Allied landings in Europe. At its peak, more than one hundred V-1s a day were fired at south-east England, 9,521 in total, decreasing in number as sites were overrun until October 1944, when the last V-1 site in range of Britain was overrun by Allied forces. After this, the V-1s were directed at the port of Antwerp and other targets in Belgium, with 2,448 V-1s being launched. The attacks stopped only a month before the war in Europe ended, when the last launch site in the Low Countries was overrun on March 29, 1945.

It took a V-1 about 15 minutes to travel from its launch pad in Calais, France to the heart of London…a distance of nearly 95 miles. Nearly 10,000 V-1s were launched from sites in Northern France over an 80 day period beginning in June 1944. Their targets included London, as well as other cities in southern England. At the peak of the bombing, more than 100 rockets were hitting Britain daily. Casualties climbed to 22,000 people, with more than 6,000 of them fatalities. Hitler hoped his new weapons would crush British morale, bringing

surrender. More V-1s would later be fired from inside Germany itself at Liege and the port of Antwerp. Hitler had underestimated the British, however. The British operated an arrangement of air defenses, including anti-aircraft guns and fighter aircraft, to intercept the bombs before they reached their targets as part of Operation Crossbow, while the launch sites and underground V-1 storage depots were targets of strategic bombings.

surrender. More V-1s would later be fired from inside Germany itself at Liege and the port of Antwerp. Hitler had underestimated the British, however. The British operated an arrangement of air defenses, including anti-aircraft guns and fighter aircraft, to intercept the bombs before they reached their targets as part of Operation Crossbow, while the launch sites and underground V-1 storage depots were targets of strategic bombings.