british

In every branch of service, and every war, the US servicemen are given a handbook. The book is filled with useful information, meant to make the transition from civilian to soldier a successful one, even if it is not an easy one. No young civilian preparing to go to war really has a good idea of what they are getting into. I suppose more of them do these days, than their World War and prior wars era counterparts. Nevertheless, each of them is proceeding head on into a massive reality check. The handbook can be a sobering little book, especially when the new soldier reads the chapter that recommends the writing of a will. The need for a Last Will and Testament will become crystal clear when the soldier sees his (or her) first battle. The sight of dead bodies takes away any misconception the soldier might have of their own mortality, and the possibility that they may have been given a one-way ticket to this battle.

In every branch of service, and every war, the US servicemen are given a handbook. The book is filled with useful information, meant to make the transition from civilian to soldier a successful one, even if it is not an easy one. No young civilian preparing to go to war really has a good idea of what they are getting into. I suppose more of them do these days, than their World War and prior wars era counterparts. Nevertheless, each of them is proceeding head on into a massive reality check. The handbook can be a sobering little book, especially when the new soldier reads the chapter that recommends the writing of a will. The need for a Last Will and Testament will become crystal clear when the soldier sees his (or her) first battle. The sight of dead bodies takes away any misconception the soldier might have of their own mortality, and the possibility that they may have been given a one-way ticket to this battle.

While many of the things contained in the handbook are sobering and even quite scary for the soldiers, there are some things contained therein that have a much more practical usage, and a few that looking back, anyway, are just a little bit funny. One such tidbit contained in the US servicemen’s World War II handbook was the simple statement that, “The British don’t know how to make a good cup of coffee. You don’t know how to make a good cup of tea—it’s an even swap.” I suppose that statement is true, at least as it pertains to the fact that British “bad coffee” is an even swap with US “bad tea.” I don’t think they US government was trying to “bad-mouth” the Brits, but rather that they were simply stating a fact. If the men were in a British camp, they simply shouldn’t ask for a cup of coffee, because they would be sorely disappointed in what they were served.

Like the warning labels of items these days, like not to shower with a running blow dryer, or to shut off the engine before trying to remove the fan belt on your car, the point was to make the reader aware of the ramifications of making such bad choices. Still, some “warnings” make more sense than others…or do they? While the electricity problem of the wet running blow dryer and the finger removal outcome of putting one’s  hand out to touch a fast-moving fan belt, seem like rather stupid wisdom (is there is such a phrase), the idea that a person would automatically make a bad cup of coffee, simply because they are British, seems equally ridiculous. Nevertheless, the US servicemen were warned to expect “bad coffee” from the British, so that they were prepared to either drink tea with the Brits, or swallow down the offending coffee so as not to offend the Brits. I’m sure that much of the rest of the handbook contained valuable information, but it is possible that the most valuable information contained in the World War II US servicemen’s handbook, was intended to avoid the notion that the Brit might have poisoned them with the British coffee.

hand out to touch a fast-moving fan belt, seem like rather stupid wisdom (is there is such a phrase), the idea that a person would automatically make a bad cup of coffee, simply because they are British, seems equally ridiculous. Nevertheless, the US servicemen were warned to expect “bad coffee” from the British, so that they were prepared to either drink tea with the Brits, or swallow down the offending coffee so as not to offend the Brits. I’m sure that much of the rest of the handbook contained valuable information, but it is possible that the most valuable information contained in the World War II US servicemen’s handbook, was intended to avoid the notion that the Brit might have poisoned them with the British coffee.

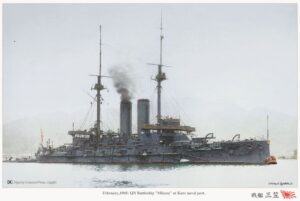

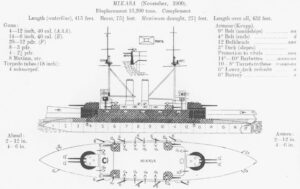

It is not usually my habit to talk about the spectacular ships built by our nation’s enemies, but IJN Mikasa might be a worthy exception. The Mikasa is a “pre-dreadnought” battleship built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in the late 1890s and is the only ship of her class. I didn’t know what a “pre-dreadnought” ship was, so I looked into it. “Pre-dreadnoughts were battleships built before 1906, when HMS Dreadnought was launched. Dreadnoughts were more powerful battleships that followed the design of HMS Dreadnought and so made pre-dreadnoughts obsolete.” The ship displaced over 15,000 long tons, with a crew of over 800 men.

It is not usually my habit to talk about the spectacular ships built by our nation’s enemies, but IJN Mikasa might be a worthy exception. The Mikasa is a “pre-dreadnought” battleship built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in the late 1890s and is the only ship of her class. I didn’t know what a “pre-dreadnought” ship was, so I looked into it. “Pre-dreadnoughts were battleships built before 1906, when HMS Dreadnought was launched. Dreadnoughts were more powerful battleships that followed the design of HMS Dreadnought and so made pre-dreadnoughts obsolete.” The ship displaced over 15,000 long tons, with a crew of over 800 men.

While she might not have been as powerful, IJN Mikasa was nevertheless a well-built ship, that was able to withstand more than most ships of her time. Named after Mount Mikasa in Nara, Japan, she served as the flagship of Vice Admiral Togo Heihachiro throughout the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. That war included the Battle of Port Arthur, which occurred on the second day of the war, as well as the Battles of the Yellow Sea and Tsushima. Just a few days after the Russo-Japanese War ended, Mikasa’s magazine (a ship’s magazine is where the powder and shells are stored) suddenly exploded and sank the ship. The explosion killed 251 men. Shortly before the Mikasa’s fatal accident, the ship had been involved in the  Battle of Tsushima (May 27, 1905), during which she had shrugged off over 40 shell strikes from heavy Russian naval guns! In that battle 113 of her crew were killed or injured. While such an event would usually mean the end of a ship, IJN Mikasa was salvaged, and while her repairs took over two years to complete, she went on to serve as a coast-defense ship during World War I, and she supported Japanese forces during the Siberian Intervention in the Russian Civil War. Ironically, in 1912 a despondent sailor among her crew tried to blow the ship up once again while the ship was anchored at Kobe. In the end the ship served until 1923, after being pulled up from the drink, repaired, and recommissioned.

Battle of Tsushima (May 27, 1905), during which she had shrugged off over 40 shell strikes from heavy Russian naval guns! In that battle 113 of her crew were killed or injured. While such an event would usually mean the end of a ship, IJN Mikasa was salvaged, and while her repairs took over two years to complete, she went on to serve as a coast-defense ship during World War I, and she supported Japanese forces during the Siberian Intervention in the Russian Civil War. Ironically, in 1912 a despondent sailor among her crew tried to blow the ship up once again while the ship was anchored at Kobe. In the end the ship served until 1923, after being pulled up from the drink, repaired, and recommissioned.

IJN Mikasa was decommissioned on September 23, 1923, following the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. At that time, she was scheduled for destruction, but at the request of the Japanese government, each of the signatory countries to the treaty agreed that Mikasa could be preserved as a memorial ship. The agreement required that her hull be encased in concrete. On November 12, 1926, Mikasa was opened for display in Yokosuka in the presence of Crown Prince Hirohito and Togo. Unfortunately, the ship deteriorated under the  control of the occupation forces after the surrender of Japan in 1945. Finally, in 1955, American businessman John Rubin, who had formally lived in Barrow, England, wrote a letter to the Japan Times about the state of the ship. His letter served as the catalyst for a new restoration campaign. The Japanese public, who were widely onboard with the idea, supported the project, as did Fleet Admiral Chester W Nimitz. The ship was once again restored, and the museum version reopened in 1961. On August 5, 2009, IJN Mikasa was repainted by sailors from USS Nimitz, and she is now the only surviving example of a “pre-dreadnought” battleship in the world. IJN Mikasa is located in the town of its construction, Barrow-in-Furness, near Mikasa Street on Walney Island.

control of the occupation forces after the surrender of Japan in 1945. Finally, in 1955, American businessman John Rubin, who had formally lived in Barrow, England, wrote a letter to the Japan Times about the state of the ship. His letter served as the catalyst for a new restoration campaign. The Japanese public, who were widely onboard with the idea, supported the project, as did Fleet Admiral Chester W Nimitz. The ship was once again restored, and the museum version reopened in 1961. On August 5, 2009, IJN Mikasa was repainted by sailors from USS Nimitz, and she is now the only surviving example of a “pre-dreadnought” battleship in the world. IJN Mikasa is located in the town of its construction, Barrow-in-Furness, near Mikasa Street on Walney Island.

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

The sinking, brought with it a claim from the Germans that the submarine’s crew had  followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave

followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave  those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

The sinking of RMS Falaba, and Thrasher’s subsequent death, was mentioned again in a memorandum sent by the US government, which was drafted by President Woodrow Wilson himself and addressed to the German government after the German submarine attack on the British passenger ship Lusitania on May 7, 1915, in which 1,201 people were drowned, including 128 Americans. President Wilson’s note was clearly a warning, calling for the US and Germany to come to a full and complete understanding as to the grave situation which had resulted from the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. In response to the warning, Germany abandoned the policy shortly thereafter. However, the policy abandonment was reversed in early 1917, and that was the final straw that put the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917.

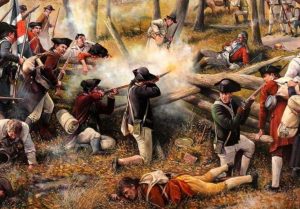

The British tried very hard to keep the United States colonies of Great Britain. The odds were in their favor, but they badly misjudged the determination of the early pioneers of this country. The Revolutionary War would bear that out. On February 5, 1779, George Rogers Clark departed Kaskaskia on the Mississippi River with a force of approximately 170 men, including Kentucky militia and French volunteers. Their goal was to take Fort Sackville (Fort Vincennes, at that time), British garrison under Lieutenant-Governor Henry Hamilton. The men traveled across what is now the state of Illinois, a journey of about 180 miles, much of it covered by deep and icy flood water until they reached Fort Sackville at Vincennes, in what is now Indiana. They reached the Embarras River on February 17th, placing them only 9 miles from Fort Sackville. Unfortunately, the river was too high to cross there, so they followed the Embarrass River down to the Wabash River, where the next day they began to build boats. Moral was low, because they had been without food for the last two days, and Clark struggled to keep his men from deserting. Clark later wrote that “I conducted myself in such a manner that caused the whole to believe that I had no doubt of success, which kept their spirits up.” He really had no choice, no matter what his true feelings were on the matter. Still, in a February 20 entry in Captain Bowman’s Field Journal, he describes the men in camp as “very quiet but hungry; some almost in despair; many of the creole volunteers talking of returning.” The situation grew more bleak by the day, and on February 22, Bowman reports that they still have “No provisions yet. Lord, help us!” and that “Those that were weak and famished from so much fatigue went in the canoes” as they marched towards toward Vincennes.

The British tried very hard to keep the United States colonies of Great Britain. The odds were in their favor, but they badly misjudged the determination of the early pioneers of this country. The Revolutionary War would bear that out. On February 5, 1779, George Rogers Clark departed Kaskaskia on the Mississippi River with a force of approximately 170 men, including Kentucky militia and French volunteers. Their goal was to take Fort Sackville (Fort Vincennes, at that time), British garrison under Lieutenant-Governor Henry Hamilton. The men traveled across what is now the state of Illinois, a journey of about 180 miles, much of it covered by deep and icy flood water until they reached Fort Sackville at Vincennes, in what is now Indiana. They reached the Embarras River on February 17th, placing them only 9 miles from Fort Sackville. Unfortunately, the river was too high to cross there, so they followed the Embarrass River down to the Wabash River, where the next day they began to build boats. Moral was low, because they had been without food for the last two days, and Clark struggled to keep his men from deserting. Clark later wrote that “I conducted myself in such a manner that caused the whole to believe that I had no doubt of success, which kept their spirits up.” He really had no choice, no matter what his true feelings were on the matter. Still, in a February 20 entry in Captain Bowman’s Field Journal, he describes the men in camp as “very quiet but hungry; some almost in despair; many of the creole volunteers talking of returning.” The situation grew more bleak by the day, and on February 22, Bowman reports that they still have “No provisions yet. Lord, help us!” and that “Those that were weak and famished from so much fatigue went in the canoes” as they marched towards toward Vincennes.

Their first real break came on February 20th, when they captured five hunters from Vincennes, who were traveling by boat. In their complete surprise, they revealed that Clark and his little army had not yet been detected. They also revealed that the people of Vincennes were sympathetic to the Americans, and not the British. The news served to revive the men, and the next day, they crossed the Wabash by canoe, leaving their packhorses behind. On foot, they marched towards Vincennes. It was still not an easy go of it, and sometimes the men found themselves in water up to their shoulders. A 4-mile-wide flooded plain made the last few days the hardest, and they were forced to use the canoes to shuttle the most weary and weakened men from high point to high point. Shortly before reaching Vincennes, they encountered a villager known to be a friend, who informed Clark that they were still unsuspected. Clark sent the man ahead with a letter to the inhabitants of Vincennes, warning them that he was just about to arrive with an army and that everyone should stay in their homes unless they wanted to be considered an enemy. The message was read in the public square, and no one went to the fort to warn Hamilton. Clark secured the surrender of the British garrison at 10am on February 25, 1779, after brutally killing five captive Native Americans who were British alleys, within view of the fort, probably to scare those inside.

Prior to the surrender of Fort Sackville, the British truly thought that they were on track to win this war and retain their control, but the surrender of Fort Sackville took the wind out of their sails, and literally marked the beginning of the end of British domination in America’s western frontier. There were only 40 British soldiers in Fort Sackville, and an equal number of mixed French volunteers and French settlers who fought on both sides of the American Revolution. The French portion of Hamilton’s force was reluctant to fight once they realized their compatriots had allied themselves with Clark. To further confuse those in the fort, Clark managed to make his 170 men seem more like 500 by unfurling flags suitable to a larger number of troops. The able woodsmen filling Clark’s ranks were able to fire at a rapid rate. That caused Hamilton to believe that he was surrounded by a substantial army. While Hamilton was occupied, Clark began tunneling under the fort planning to explode the gunpowder stores within it.

When a Native American raiding party attempted to return to the fort from the Ohio Valley, Clark’s men killed or captured all of them. The public tomahawk executions served upon five of the captives frightened the British, assuming that theirs might be a similar fate in Clark’s hands. When the British surrendered to Clark’s men, the Native Americans understood fully that they could no longer rely on the British to protect them from the Patriots. The British finally understood too, that they were no match for the determined patriots. The United States was finally free of the British.

They say that genius can be the closest thing to crazy, but I don’t really know how true that is. Sometimes I think that when a person is a genius, people drive them crazy. It’s the novelty of the thing, I suppose. People find out that the genius has a super high IQ, and they all seem to want something from them. Many people don’t really care about the genius as a person, just about how they might be able to make money off of them somehow. Not every inventor is a genius, but some of them are, as are some mathematicians, doctors, teachers, writers, and many other people too.

They say that genius can be the closest thing to crazy, but I don’t really know how true that is. Sometimes I think that when a person is a genius, people drive them crazy. It’s the novelty of the thing, I suppose. People find out that the genius has a super high IQ, and they all seem to want something from them. Many people don’t really care about the genius as a person, just about how they might be able to make money off of them somehow. Not every inventor is a genius, but some of them are, as are some mathematicians, doctors, teachers, writers, and many other people too.

Sometimes the demands placed on these geniuses gets to be so heavy, that they might just snap. I don’t mean that they might go insane, although some of them have. The thing that seems to happen most, however, is that they might just decide to disappear. Several geniuses have simply vanished,  including William Sidis (who graduated from Harvard at 16, only to go into hiding, going from city to city and job to job), JD Salinger (author of Catcher in the Rye, who left Manhattan in 1953 to live on a “90-acre compound” in Cornish, NH. He remained there until his death in 2010, at age 91, saying he loved to write, but publishing was a terrible invasion of his privacy), Ettore Majorana (a theoretical physicist was considered one of the most deeply brilliant men in the world by Enrico Fermi, creator of the first nuclear reactor. One day he drained his bank account and simply vanished), David Thorne (an architect received so much attention for his work on jazz giant Dave Brubeck’s house in 1954, that he changed his professional name in the ‘60s to Beverly Thorne, got an unlisted phone number, and didn’t “resurface” until the 1980s), and Nick Gill (who at 21, was the youngest-ever British chef to win a Michelin star. He seemed destined for a life of fame and fortune and was hailed as a culinary genius. One day he told his brother he was going to disappear, and to “please, not look for him,” never to be seen again).

including William Sidis (who graduated from Harvard at 16, only to go into hiding, going from city to city and job to job), JD Salinger (author of Catcher in the Rye, who left Manhattan in 1953 to live on a “90-acre compound” in Cornish, NH. He remained there until his death in 2010, at age 91, saying he loved to write, but publishing was a terrible invasion of his privacy), Ettore Majorana (a theoretical physicist was considered one of the most deeply brilliant men in the world by Enrico Fermi, creator of the first nuclear reactor. One day he drained his bank account and simply vanished), David Thorne (an architect received so much attention for his work on jazz giant Dave Brubeck’s house in 1954, that he changed his professional name in the ‘60s to Beverly Thorne, got an unlisted phone number, and didn’t “resurface” until the 1980s), and Nick Gill (who at 21, was the youngest-ever British chef to win a Michelin star. He seemed destined for a life of fame and fortune and was hailed as a culinary genius. One day he told his brother he was going to disappear, and to “please, not look for him,” never to be seen again).

It isn’t known, as to why these geniuses would decide that they no longer wanted to be a part of the world, nor

are they to only people to do this by any means. Nevertheless, they seem to have one thing in common, their genius skill or knowledge seemed to take over their whole life, and people wouldn’t leave them alone, but rather hounded them unmercifully. I think I can understand how that would be enough to make someone want to disappear, but most people don’t actually go so far as to take that step. It is a rather extreme step to take, and for all we know some of these might have been killed or committed suicide. The sad reality for these genius minds is that the fame and constant pressure of celebrity was too much for them, and they just checked out, because the burden of knowledge was just too much for them.

are they to only people to do this by any means. Nevertheless, they seem to have one thing in common, their genius skill or knowledge seemed to take over their whole life, and people wouldn’t leave them alone, but rather hounded them unmercifully. I think I can understand how that would be enough to make someone want to disappear, but most people don’t actually go so far as to take that step. It is a rather extreme step to take, and for all we know some of these might have been killed or committed suicide. The sad reality for these genius minds is that the fame and constant pressure of celebrity was too much for them, and they just checked out, because the burden of knowledge was just too much for them.

The Rock of Gibraltar is a unique rock located in the British territory of Gibraltar, near the southwestern tip of Europe on the Iberian Peninsula, and near the entrance to the Mediterranean. It is a huge monolithic limestone promontory that stands high above the water, although it actually sits on the edge of the land. During World War II, the rock was actually a war tool, and an amazing one at that. The British Army dug a maze of defensive tunnels inside the rock during the war, and the massive cliff is famous for the more than 30 miles of cleared space that served as a housing area for guns, ammunition, barracks, and even hospitals for wounded soldiers.

The Rock of Gibraltar is a unique rock located in the British territory of Gibraltar, near the southwestern tip of Europe on the Iberian Peninsula, and near the entrance to the Mediterranean. It is a huge monolithic limestone promontory that stands high above the water, although it actually sits on the edge of the land. During World War II, the rock was actually a war tool, and an amazing one at that. The British Army dug a maze of defensive tunnels inside the rock during the war, and the massive cliff is famous for the more than 30 miles of cleared space that served as a housing area for guns, ammunition, barracks, and even hospitals for wounded soldiers.

Recently, it was discovered that the rock held another, previously unknown secret use. Hidden in the famous rock is a secret chamber, known as the “Stay Behind Cave.” The cave measures 45 x 16 x 8 feet, and it has long been the site of a top-secret World War II plot called Operation Tracer. British Intelligence found out in 1940, that Hitler was planning to invade Gibraltar and cut off Great Britain from the rest of the British Empire. It was another part of their evil plan to take over the world, and they needed Britain out of the way to accomplish their objective. Once the British knew about this plot, the British Admirals suggested that a secret room be constructed within the Rock of Gibraltar, where six men would hide and observe from two small openings any movement they could see on the harbor.

Six men were selected. One of the men even agreed to Operation Tracer before he was even told what it was. That fact doesn’t shock me as much as the other men knowing about it and still being willing to participate. The plan was to seal the six men inside the secret chamber with enough supplies to last them a year (some say the food stores could have actually carried the men for 7 years) was put into action. The plan had to take in any eventuality, so it was said that if one of the men were to die, they would be buried in the brick floor. The only way the men could escape back into the outside world would be if Germany was defeated before the year’s-worth of supplies ran out. Construction on the chamber began in 1941 and ended in 1942. It featured a radio room, 10,000 gallons of water, power generators, and other necessities.

The men were rigorously trained for the upcoming mission, but just before Operation Tracer could officially begin, Hitler changed course and started to focus more on the Eastern Front. The men were never required to begin their mission. The mission aborted, the equipment was removed and the section of the rock leading to the secret chamber was blocked off. The chamber was to be kept top secret. I suppose in case it was ever  needed in a future war, but persistent rumors floated around about a secret chamber, and people continued to search for it. To me it is encouraging to know that it took people until December 26, 1996, to locate what they thought might be the chamber. That tells me that had the men been required to live in the room, they would probably have done so in absolute secrecy and safety. The suspicion about the room would persist for another decade, until finally, one of the six men who was supposed to partake in Operation Tracer confirmed that the room the explorers found in 1996, was indeed the room that was built for their top-secret operation all those years ago. It may be one of the best-kept secrets of World War II.

needed in a future war, but persistent rumors floated around about a secret chamber, and people continued to search for it. To me it is encouraging to know that it took people until December 26, 1996, to locate what they thought might be the chamber. That tells me that had the men been required to live in the room, they would probably have done so in absolute secrecy and safety. The suspicion about the room would persist for another decade, until finally, one of the six men who was supposed to partake in Operation Tracer confirmed that the room the explorers found in 1996, was indeed the room that was built for their top-secret operation all those years ago. It may be one of the best-kept secrets of World War II.

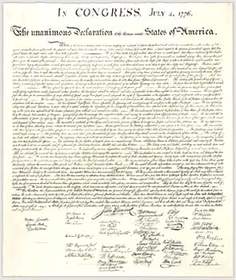

Most of us think of everything changing instantly when the Declaration of Independence was signed, and officially it did, but there was more to it than that. After years of oppression under the rulership of the British, the citizens of the 13 colonies had had enough. They formed the Continental Congress. The term “Continental Congress” most specifically refers to the First and Second Congresses of 1774–1781 and, at the time, was also used to refer to the Congress of the Confederation of 1781–1789, which operated as the first national government of the United States until being replaced under the Constitution of the United States. The 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress represented the 13 colonies, 12 of which voted to approve the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776…our accepted day of Independence. The signing of the United States Declaration of Independence actually occurred on August 2, 1776, at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, which later to become known as Independence Hall. I suppose that a purist might insist that August 2nd should be our Independence Day, but the 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress felt like once it was agreed upon, it was done. The signing was merely a technicality.

Most of us think of everything changing instantly when the Declaration of Independence was signed, and officially it did, but there was more to it than that. After years of oppression under the rulership of the British, the citizens of the 13 colonies had had enough. They formed the Continental Congress. The term “Continental Congress” most specifically refers to the First and Second Congresses of 1774–1781 and, at the time, was also used to refer to the Congress of the Confederation of 1781–1789, which operated as the first national government of the United States until being replaced under the Constitution of the United States. The 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress represented the 13 colonies, 12 of which voted to approve the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776…our accepted day of Independence. The signing of the United States Declaration of Independence actually occurred on August 2, 1776, at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, which later to become known as Independence Hall. I suppose that a purist might insist that August 2nd should be our Independence Day, but the 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress felt like once it was agreed upon, it was done. The signing was merely a technicality.

For the British government, neither of those days was acceptable, nor was the day they found out about the plan of the 13 colonies to gain their independence. In fact, that day…August 10, 1776, was the least acceptable day of all, because the British had no intention of giving the Colonies their independence…not without a fight anyway. When the news reached London, the British saw the conflict, centered in Massachusetts, as a local uprising within the British empire. Some Americans saw it that way too, but the reality is that the Declaration of Independence transformed the 13 British colonies into American states. King George III saw it as a colonial rebellion, but the Americans saw it as a struggle for their rights as British citizens. However, when Parliament continued to oppose any reform and remained unwilling to negotiate with the American rebels and instead hired Hessians, German mercenaries, to help the British army crush the rebellion, the Continental Congress began to pass measures abolishing British authority in the colonies. It was a brave move that would cost many of the 56 signers more than they could ever have imagined.

Following the signing of the Declaration of Independence, five of the signers were captured by the British and labeled as traitors. They were tortured before they died. Twelve of them had their homes ransacked and burned. Two lost their sons, who served in the Revolutionary War. Another two had sons captured, and nine of the 56 fought and died from wounds or hardships of the Revolutionary War. These men knew the risks they were taking. They knew that signing the Declaration of Independence very likely would cost them their lives. Nevertheless, they also knew that they couldn’t let the tyranny continue any longer. They had come to America to escape the tyrannical British government, and they could not allow the British government to make them slaves again. They signed, knowing they would likely die, but they saw no other way. These men weren’t soldiers…so, who were they. Twenty-four were lawyers and jurists. Eleven were merchants. Nine were farmers and plantation owners. All of them were men of means and well-educated, but they signed the Declaration of

Independence, knowing that the penalty would be death if they were captured. These men had their livelihood threatened and destroyed, their homes confiscated and sold, and some were threatened so badly that they had to constantly move their families from place to place. Still, not one of them saw this as one option of many. When it came to taking their country back, they saw it as the only option.

Independence, knowing that the penalty would be death if they were captured. These men had their livelihood threatened and destroyed, their homes confiscated and sold, and some were threatened so badly that they had to constantly move their families from place to place. Still, not one of them saw this as one option of many. When it came to taking their country back, they saw it as the only option.

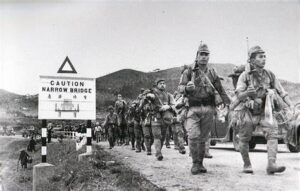

During their reign of terror, Japan, like Germany had their sights set on world domination. Japanese troops landed in Hong Kong on December 18, 1941, and an immediate slaughter began. The process started with a week of air raids over Hong Kong, which was a British Crown Colony at the time. Then on December 17, Japanese envoys paid a visit to Sir Mark Young, who was at that time, the British governor of Hong Kong.

During their reign of terror, Japan, like Germany had their sights set on world domination. Japanese troops landed in Hong Kong on December 18, 1941, and an immediate slaughter began. The process started with a week of air raids over Hong Kong, which was a British Crown Colony at the time. Then on December 17, Japanese envoys paid a visit to Sir Mark Young, who was at that time, the British governor of Hong Kong.

The envoys’ message was simple: “The British garrison there should simply surrender to the Japanese—resistance was futile.” The envoys were sent home with the following retort: “The governor and commander in chief of Hong Kong declines absolutely to enter into negotiations for the surrender of Hong Kong…”

The unsuccessful negotiations brought a swift wave of Japanese troops, who in retaliation for the refused surrender, landed in Hong Kong with artillery fire for cover and the following order from their commander: “Take no prisoners.” The troops quickly overran a volunteer antiaircraft battery, and the Japanese invaders roped together the captured soldiers. In a complete disregard for human life, a complete disregard for the Geneva Convention rules, or any rules of common decency, the Japanese proceeded to bayonet them to death. Even those who offered no  resistance, such as the Royal Medical Corps, were led up a hill and killed. They showed no mercy, just hate and evil. Following the initial slaughter, the Japanese took control of key reservoirs. With the water under their control, they threatened the British and Chinese inhabitants with a slow death by thirst. With their backs against a wall, the British finally surrendered control of Hong Kong on Christmas Day.

resistance, such as the Royal Medical Corps, were led up a hill and killed. They showed no mercy, just hate and evil. Following the initial slaughter, the Japanese took control of key reservoirs. With the water under their control, they threatened the British and Chinese inhabitants with a slow death by thirst. With their backs against a wall, the British finally surrendered control of Hong Kong on Christmas Day.

On that same day, the War Powers Act was passed by Congress, authorizing the president to initiate and terminate defense contracts, reconfigure government agencies for wartime priorities, and regulate the freezing of foreign assets. It also permitted him to censor all communications coming in and leaving the country. President Franklin D Roosevelt appointed the executive news director of the Associated Press, Byron Price, as director of censorship. Although invested with the awesome power to restrict and withhold news, Price took no extreme measures, allowing news outlets and radio stations to self-censor, which they did. Most top-secret information, including the construction of the atom  bomb, remained just that…strangely, but then those were different times.

bomb, remained just that…strangely, but then those were different times.

“The most extreme use of the censorship law seems to have been the restriction of the free flow of “girlie” magazines to servicemen…including Esquire, which the Post Office considered obscene for its occasional saucy cartoons and pinups. Esquire took the Post Office to court, and after three years the Supreme Court ultimately sided with the magazine.” It amazes me just how much times have changed. These days the “girlie” trash is totally acceptable, but truth is censored and lies are allowed. Too bad we are so far out from those days.

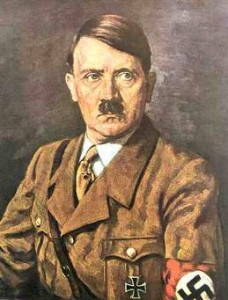

When Hitler began his reign of terror, he fully expected that he would meet with little resistance from the people he was attempting to control, but that really never turned out to be the case. Even some of those who aligned themselves with him at first, rebelled later. Hitler found that out when, on November 18, 1940, he met with Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano over Mussolini’s disastrous invasion of Greece.

When Hitler began his reign of terror, he fully expected that he would meet with little resistance from the people he was attempting to control, but that really never turned out to be the case. Even some of those who aligned themselves with him at first, rebelled later. Hitler found that out when, on November 18, 1940, he met with Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano over Mussolini’s disastrous invasion of Greece.

Mussolini had led Hitler to believe that he had no intention of attempting to invade Greece. Then, he surprised everyone with a attempted invasion of Greece. Even his ally…Hitler, was caught off guard, since Mussolini had led Hitler to believe he had no such intention. Even Mussolini’s own chief of army staff only found out about the invasion after the fact!!

Mussolini was warned against trying to invade Greece. Everyone around him knew that the Greek people were determined to hold onto their freedom, and that the Italian Army was woefully unprepared for such an attack. Even his own generals warned of a lack of preparedness on the part of his military. Nevertheless, and despite the fact that it would mean getting bogged down in a mountainous country during the rainy season against an army willing to fight tooth and nail to defend its autonomy, Mussolini moved ahead mostly out of sheer arrogance, convinced he could defeat the “inferior Greeks” in a matter of days. He also knew a secret, that millions of Lire (The primary unit of currency in Italy, Malta, San Marino, and the Vatican City before the adoption of the Euro) had been put aside to bribe Greek politicians and generals not to resist the Italian invasion. The whole bribe idea didn’t work out too well, however. Whether the money ever made it past the Italian fascist agents delegated with the responsibility is unclear, but if it did, it clearly made no difference. The Greeks pushed the Italian invaders back into Albania after just one week. The whole operation was a miserable failure, and the Italians spent the next three months fighting for life in a fierce, defensive battle. To make matters worse, about half the Italian fleet had been crippled by a British carrier-based attack at Taranto.

A furious Hitler severely criticized Ciano at their meeting in Obersalzberg, for opening an opportunity for the British to enter Greece and establish an airbase in Athens. That put the Brits within striking distance of valuable  oil reserves in Romania that Hitler needed for his war machine. Hitler now had to divert forces from North Africa, a high strategic priority, to Greece in order to bail Mussolini out. He actually considered leaving the Italians to fight their own way out of the mess, and considered making peace with the Greeks as a way of forestalling an Allied intervention. Nevertheless, Germany would have to invade, in April 1941, thereby adding Greece to its list of conquests…whether Hitler wanted to or not. That put the Brits within striking distance of valuable oil reserves in Romania that Hitler needed for his war machine. Hitler now had to divert forces from North Africa, a high strategic priority, to Greece in order to bail Mussolini out. He actually considered leaving the Italians to fight their own way out of the mess, and considered making peace with the Greeks as a way of forestalling an Allied intervention. Nevertheless, Germany would have to invade, in April 1941, thereby adding Greece to its list of conquests…whether Hitler wanted to or not.

oil reserves in Romania that Hitler needed for his war machine. Hitler now had to divert forces from North Africa, a high strategic priority, to Greece in order to bail Mussolini out. He actually considered leaving the Italians to fight their own way out of the mess, and considered making peace with the Greeks as a way of forestalling an Allied intervention. Nevertheless, Germany would have to invade, in April 1941, thereby adding Greece to its list of conquests…whether Hitler wanted to or not. That put the Brits within striking distance of valuable oil reserves in Romania that Hitler needed for his war machine. Hitler now had to divert forces from North Africa, a high strategic priority, to Greece in order to bail Mussolini out. He actually considered leaving the Italians to fight their own way out of the mess, and considered making peace with the Greeks as a way of forestalling an Allied intervention. Nevertheless, Germany would have to invade, in April 1941, thereby adding Greece to its list of conquests…whether Hitler wanted to or not.

When we think about the enemies of war, we usually think of two nations that unequivocally hate each other. It is thought that every member of teach nation totally hates every member of the other, but that is not even logical. It doesn’t matter what nation you are talking about, the people of those nations are thoughts to hate each other, and many of them do, but nt all of them do. Not everyone loved war, and not everyone loves killing.

When we think about the enemies of war, we usually think of two nations that unequivocally hate each other. It is thought that every member of teach nation totally hates every member of the other, but that is not even logical. It doesn’t matter what nation you are talking about, the people of those nations are thoughts to hate each other, and many of them do, but nt all of them do. Not everyone loved war, and not everyone loves killing.

World War II was the deadliest wars in world history. It seemed that everyone hated everyone else, or at least that those from the one side (the Allied Powers) hated the other (the Axis of Evil). That wasn’t true either. The leaders probably hated each other, but the people of the nations were caught in the middle of the hatred of their leaders. Many of the people, civilians and military alike were family people, they had a love of others. Many of the people who fought in World War II had no idea of the horrors that were taking place. When they finally found out about it, they were absolutely horrified.

Still, those who fought in the war, knew some of the casualties of the war. A fighter pilot can’t fly over an expanse of an ocean battlefield and not see the losses taking place. For a fighter pilot or a bomber crew, it was not only possible to see the devastation, but they could also imagine what was going on below them as ships sink so quickly that the men onboard cannot escape. To add to the horror, the fact that these ships were his by torpedoes, bombs from the planes, bullets from the planes, and the planes themselves brought the added horror of fire and burning bodies. If a pilot let himself think about it, I think it would be possible to become physically ill at the thought of the horrors going on below them.

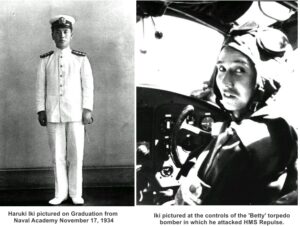

One fighter pilot felt that very deeply. During a sea battle in the Pacific Ocean in December 1940, two Royal Navy ships, the HMS Prince of Wales and the HMS Repulse were sunk by Japanese fighters. The scene must have been horrific for the pilots above, whether they were British or Japanese, they knew that men were dying horrific deaths below them. The loss of life so impacted on Japanese fighter pilot that he came back to the spot

the next day and dropped two wreaths on the water. His action was to commemorate the dead from both sides during WWII. Japanese Flight Lieutenant Haruki Iki flew to the location of the battle and dropped the two wreaths over the seas. It was a simple act, but it was also a profound act. It showed that while the nations were enemies, the people of the nations were not necessarily enemies too. It also showed that even enemies can have compassion on the other side. War is not all about hate, it is also about being caught in the middle, with no way out but to fight.

the next day and dropped two wreaths on the water. His action was to commemorate the dead from both sides during WWII. Japanese Flight Lieutenant Haruki Iki flew to the location of the battle and dropped the two wreaths over the seas. It was a simple act, but it was also a profound act. It showed that while the nations were enemies, the people of the nations were not necessarily enemies too. It also showed that even enemies can have compassion on the other side. War is not all about hate, it is also about being caught in the middle, with no way out but to fight.