Politics

Sometimes, a business starts up and then can’t make a go of it. Whatever the reason, things just don’t work out. Such was the case with a 1690 newspaper called Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick. This newspaper was published for the first and last time on September 25, 1690, making it the shortest business on record.

Sometimes, a business starts up and then can’t make a go of it. Whatever the reason, things just don’t work out. Such was the case with a 1690 newspaper called Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick. This newspaper was published for the first and last time on September 25, 1690, making it the shortest business on record.

It would seem like such a business venture wouldn’t hold a very significant place in history, but it did have one distinction that gave it an important place. It was the first multi-page newspaper published in the Americas. Before then, single-page newspapers, called broadsides, were published in the English colonies and printed in Cambridge in 1689. The first edition of Publick Occurrences was published in Boston, then a city in the Dominion of New England, and was intended to be published monthly, “or, if any Glut of Occurrences happen, oftener.” It was printed by American Richard Pierce of Boston, and it was edited by Benjamin Harris, who had previously published a newspaper in London. The paper contained four 6 by 10 inch pages, but filled only three of them…not bad for a new newspaper.

The second edition was never printed because the paper was shut down by the Colonial government on September 29, 1690, who issued an order as follows: “Whereas some have lately presumed to Print and Disperse a Pamphlet,  Entitled, Publick Occurrences, both Forreign and Domestick: Boston, Thursday, September 25th, 1690. Without the least Privity and Countenace of Authority. The Governour and Council having had the perusal of said Pamphlet, and finding that therein contained Reflections of a very high nature: As also sundry doubtful and uncertain Reports, do hereby manifest and declare their high Resentment and Disallowance of said Pamphlet, and Order that the same be Suppressed and called in; strickly forbidden any person or persons for the future to Set forth any thing in Print without License first obtained from those that are or shall be appointed by the Government to grant the same.”

Entitled, Publick Occurrences, both Forreign and Domestick: Boston, Thursday, September 25th, 1690. Without the least Privity and Countenace of Authority. The Governour and Council having had the perusal of said Pamphlet, and finding that therein contained Reflections of a very high nature: As also sundry doubtful and uncertain Reports, do hereby manifest and declare their high Resentment and Disallowance of said Pamphlet, and Order that the same be Suppressed and called in; strickly forbidden any person or persons for the future to Set forth any thing in Print without License first obtained from those that are or shall be appointed by the Government to grant the same.”

Of course, in those days, we were not an independent nation, and the Constitution did not exist. Freedom of the press…or any of the other freedoms that our soldiers and our nation have fought to give us, didn’t exist either. England was the ruler and the law, and we had to obey…for a time. Soon enough, change would come, as would freedom, and every kind of newspaper and other types of information sources imaginable.

These days, patriotism seems to be constantly under fire. The nation has basically taken sides on the issue. There are those who hate this country and all it stands for, and those who love this country despite its faults and any negative historical events. I am a patriot, and it is my belief that history is history, mistakes and all. It can’t be changed by tearing down a few statues, and certainly not by stomping on our flag. The patriots of this time feel the same as the patriots of the Vietnam era…”Our Flag, Love it or Leave.” I find it strange to think that this era is really no different than that era, or any other era of American history, or in fact, in the history of any nation. There are those who love their nation and are loyal to it, and those who tend to blow with the wind…only showing faithfulness when it suits their own agenda. In my opinion and the opinion of every patriot, these people who turn on our country just because things aren’t going their way, are traitors, and should be treated as such.

These days, patriotism seems to be constantly under fire. The nation has basically taken sides on the issue. There are those who hate this country and all it stands for, and those who love this country despite its faults and any negative historical events. I am a patriot, and it is my belief that history is history, mistakes and all. It can’t be changed by tearing down a few statues, and certainly not by stomping on our flag. The patriots of this time feel the same as the patriots of the Vietnam era…”Our Flag, Love it or Leave.” I find it strange to think that this era is really no different than that era, or any other era of American history, or in fact, in the history of any nation. There are those who love their nation and are loyal to it, and those who tend to blow with the wind…only showing faithfulness when it suits their own agenda. In my opinion and the opinion of every patriot, these people who turn on our country just because things aren’t going their way, are traitors, and should be treated as such.

There have been a number of traitors in our nations history, and I’m sure there will be many more, but one of the most famous of them all was Benedict Arnold. On this day in 1780, during the American Revolution, an American General named Benedict Arnold met with a British Major named John Andre to discuss the treasonous act of handing over West Point to the British. In return Arnold was promised of a large sum of money and a high position in the British army. The plot was foiled and Arnold, who was once considered an American hero, became synonymous with the word “traitor.” Benedict Arnold was not always a low life traitor. He was actually  born into a well-respected family in Norwich, Connecticut, on January 14, 1741. He apprenticed with an apothecary and was a member of the militia during the French and Indian War from 1754 to 1763. Later, he became a successful trader and then joined the Continental Army when the Revolutionary War broke out between Great Britain and its 13 American colonies in 1775. When the war ended in 1783, the colonies had won their independence from Britain and formed a new nation…the United States.

born into a well-respected family in Norwich, Connecticut, on January 14, 1741. He apprenticed with an apothecary and was a member of the militia during the French and Indian War from 1754 to 1763. Later, he became a successful trader and then joined the Continental Army when the Revolutionary War broke out between Great Britain and its 13 American colonies in 1775. When the war ended in 1783, the colonies had won their independence from Britain and formed a new nation…the United States.

During the war, Benedict Arnold proved himself a brave and skillful leader, helping Ethan Allen’s troops capture Fort Ticonderoga in 1775 and then participating in the unsuccessful attack on British Quebec later that year, which earned him a promotion to brigadier general. Arnold distinguished himself in campaigns at Lake Champlain, Ridgefield and Saratoga, and gained the support of George Washington. However, Arnold also had some enemies within the military and in 1777, five men of lesser rank were promoted over him. I see that there were those who were not fooled by his presumed loyalty. Over the course of the next few years, Arnold married for a second time. He and his new wife lived a lavish lifestyle in Philadelphia, accumulating a large amount of debt. The debt and the resentment Arnold felt over not being promoted faster were the motivating factors in his decision to become a turncoat.

In 1780, Arnold was given command of West Point, an American fort on the Hudson River in New York, and future home of the United States military academy, which was established in 1802. Arnold contacted Sir Henry  Clinton, head of the British forces, and proposed handing over West Point and his men. On September 21, 1780, Arnold met with Major John Andre and made his traitorous pact. Thankfully, the conspiracy was uncovered and Andre was captured and executed. Arnold, the former American patriot turned traitor, fled to the enemy side and went on to lead British troops in Virginia and Connecticut. He later moved to England, though he never received all of what he’d been promised by the British. He died in London on June 14, 1801, having never realized the greatness he thought he would achieve. Now, when people think of a traitor, they often call them a Benedict Arnold. It is a huge insult to be called that.

Clinton, head of the British forces, and proposed handing over West Point and his men. On September 21, 1780, Arnold met with Major John Andre and made his traitorous pact. Thankfully, the conspiracy was uncovered and Andre was captured and executed. Arnold, the former American patriot turned traitor, fled to the enemy side and went on to lead British troops in Virginia and Connecticut. He later moved to England, though he never received all of what he’d been promised by the British. He died in London on June 14, 1801, having never realized the greatness he thought he would achieve. Now, when people think of a traitor, they often call them a Benedict Arnold. It is a huge insult to be called that.

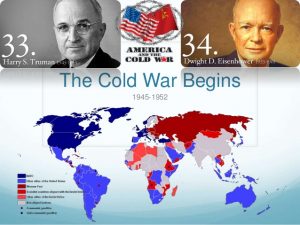

The Korean War began on June 25, 1950, when 90,000 North Korean troops, under orders from Kim Song-Ju, stormed across the 38th parallel, catching the Republic of Korea’s forces completely off guard and throwing them into a hasty southern retreat. Two days later, United States President Harry Truman announced that the United States would intervene in the conflict, and on June 28 the United Nations approved the use of force against communist North Korea. On June 30, Truman agreed to send United States ground forces to Korea, and on July 7 the Security Council recommended that all United Nations forces sent to Korea be put under United States command. The next day, General Douglas MacArthur was named commander of all United Nations forces in Korea. North Korea’s evil dictator wanted to rule the whole nation, and he wouldn’t have stopped there. He had to be stopped. The war would go on for three long years, finally ending on July 27, 1953. The Korean War was memorialized in the minds of most people with the war series, MASH, which ran far longer than the war itself. Of course, it was a semi-fictional show about a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in which the men and women did everything they could to put the injured soldiers back together after the ravages of battle, all the while, hating that they would go back to battle.

The Korean War began on June 25, 1950, when 90,000 North Korean troops, under orders from Kim Song-Ju, stormed across the 38th parallel, catching the Republic of Korea’s forces completely off guard and throwing them into a hasty southern retreat. Two days later, United States President Harry Truman announced that the United States would intervene in the conflict, and on June 28 the United Nations approved the use of force against communist North Korea. On June 30, Truman agreed to send United States ground forces to Korea, and on July 7 the Security Council recommended that all United Nations forces sent to Korea be put under United States command. The next day, General Douglas MacArthur was named commander of all United Nations forces in Korea. North Korea’s evil dictator wanted to rule the whole nation, and he wouldn’t have stopped there. He had to be stopped. The war would go on for three long years, finally ending on July 27, 1953. The Korean War was memorialized in the minds of most people with the war series, MASH, which ran far longer than the war itself. Of course, it was a semi-fictional show about a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in which the men and women did everything they could to put the injured soldiers back together after the ravages of battle, all the while, hating that they would go back to battle.

Now, we have another rogue dictator of North Korea, namely Kim Jong-un, who has developed a number of bombs, and doesn’t mind shooting them off as a warning to the rest of the world that not only is he crazy, but he is armed and crazy. Kim Jong-un lobs missiles over Japan on a regular basis, and has threatened Guam as well. Unfortunately, because of soft “leadership” on the part of President Obama, Kim Jong-un was allowed to proceed with his evil plans relatively unchecked, and now, he is an out of control leader who honestly thinks that he can control the world, and doesn’t care who he kills.

Now, we are in a position of trying to figure out how to stop Kim Jong-un. I don’t presume to know the answer to this dilemma, nor would I want to be in the shoes of those who will have to do something, because I don’t believe that this problem is going to be easily solved. I do know that something is going to have to be done.  When a dictator is willing to launch a nuclear bomb, they clearly do not care about life. All they care about is ruling the world. They don’t care about freedom, the lives of their own people or even the future of mankind. That makes them…insane, in my book. So, while I would not want to be in President Trump’s shoes concerning North Korea, I will support his decisions concerning military action, because I believe that he has the best interests of the United States and the world at heart, and I also do not believe that sanctions will work…now or ever. While I don’t think that war against North Korea would be easy, I also know that we can’t just sit idly by and let Kim Jong-un continue his rampage. It just might be time to do it again where North Korea is concerned.

When a dictator is willing to launch a nuclear bomb, they clearly do not care about life. All they care about is ruling the world. They don’t care about freedom, the lives of their own people or even the future of mankind. That makes them…insane, in my book. So, while I would not want to be in President Trump’s shoes concerning North Korea, I will support his decisions concerning military action, because I believe that he has the best interests of the United States and the world at heart, and I also do not believe that sanctions will work…now or ever. While I don’t think that war against North Korea would be easy, I also know that we can’t just sit idly by and let Kim Jong-un continue his rampage. It just might be time to do it again where North Korea is concerned.

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

A radical pamphlet of mid-July read in part, “We are going to use a little direct action on the 22nd to show that militarism can’t be forced on us and our children without a violent protest.” It was in this environment that the Preparedness Parade found itself on July 22, 1916. In spite of that, the 3½ hour long procession of some 51,329 marchers, including 52 bands and 2,134 organizations, comprising military, civic, judicial, state and municipal divisions as well as newspaper, telephone, telegraph and streetcar unions, went ahead as planned. At 2:06pm, about a half hour after the parade began, a bomb concealed in a suitcase exploded on the west side of Steuart Street, just south of Market Street, near the Ferry Building. Ten bystanders were killed by the explosion, and 40 more were wounded, in what became the worst terrorist act in San Francisco history. The city and the nation were outraged, and they declared that justice would be served.

Two radical labor leaders, Thomas Mooney and Warren K Billings, were quickly arrested and tried for the  attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.

attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.

When I think of Independence Day, I often think about how the fireworks remind me of the many battles that went on in order to win our freedom. Then, I began to wonder if there was ever a time when the 13 colonies almost didn’t become the United States. Britain was, after all, the world’s greatest superpower at the time. British soldiers fought on 5 continents and they had an amazing navy. They massacred rebels and civilians in Jamaica and India around the same time and retained those colonies. So, why not the 13 colonies of North America? There are many explanations, but the one I found most interesting seems, almost to tie to the way things are in America right now…and really all along.

When I think of Independence Day, I often think about how the fireworks remind me of the many battles that went on in order to win our freedom. Then, I began to wonder if there was ever a time when the 13 colonies almost didn’t become the United States. Britain was, after all, the world’s greatest superpower at the time. British soldiers fought on 5 continents and they had an amazing navy. They massacred rebels and civilians in Jamaica and India around the same time and retained those colonies. So, why not the 13 colonies of North America? There are many explanations, but the one I found most interesting seems, almost to tie to the way things are in America right now…and really all along.

The reality is that Britain won many times on the battlefield, but…lost in the taverns. The taverns, you say. How  could that be? Well, taverns were everywhere. They were the social network of colonial life, much like the town hall meetings, and even more, like Facebook or Twitter today. Some areas of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had taverns every few miles. People could get their mail there, hire a worker, talk to friends, sell crops, buy land, and eat a good meal. It was in these places that opinions were formed. People discussed the problems they had with British rule, and talked about how to get rid of the yoke of the Mother country.

could that be? Well, taverns were everywhere. They were the social network of colonial life, much like the town hall meetings, and even more, like Facebook or Twitter today. Some areas of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania had taverns every few miles. People could get their mail there, hire a worker, talk to friends, sell crops, buy land, and eat a good meal. It was in these places that opinions were formed. People discussed the problems they had with British rule, and talked about how to get rid of the yoke of the Mother country.

Some say that Britain might have had a chance if they had been represented in the taverns too, but I don’t think so. The time had come for Americans to think for themselves, and to run their own lives and their own country. First came the Stamp Act and the Americans protested. More oppression followed, as did the protests.  The resistance grew and grew, until war broke out. No matter what it took, the colonies were determined not to lose. The tavern meetings had accomplished what they needed to. No matter how many times it looked like Britain might win, they would not, because of…well, social networking. Social networking, when people get together to discuss right from wrong, and to discuss solutions. Sometimes the solutions are simple, and other times they create enough of a stir to bring about a revolution. No matter what the reason, the colonies were not about to lose, and because of that, we are a free nation and it was on this day, July 4, 1776 that our independence was made a reality, and we became the land of the free and the home of the brave. Happy Independence Day America!!

The resistance grew and grew, until war broke out. No matter what it took, the colonies were determined not to lose. The tavern meetings had accomplished what they needed to. No matter how many times it looked like Britain might win, they would not, because of…well, social networking. Social networking, when people get together to discuss right from wrong, and to discuss solutions. Sometimes the solutions are simple, and other times they create enough of a stir to bring about a revolution. No matter what the reason, the colonies were not about to lose, and because of that, we are a free nation and it was on this day, July 4, 1776 that our independence was made a reality, and we became the land of the free and the home of the brave. Happy Independence Day America!!

In a war, sometimes the best thing that can be done is to retreat, but that is not always easy to do. When the enemy is closing in and there seems no way of escape. Sometimes, a way of escape seems to come together in such a way that it almost seems miraculous…or maybe that is the only real explanation…a miracle. Such seemed to be the case with Britain both in Dunkirk, France, called Operation Dynamo, and again from Cherbourg, Saint Malo, Brest, and Nantes, dubbed Operation Aerial. The evacuation from Dunkirk, was most likely the largest of its kind, or at least up to that date. I suppose there might have been others since then, but I am not aware of any. During the evacuation of Dunkirk, the British managed to evacuate 338,226 soldiers…and almost unheard of amount of men were saved, by a coordinated effort using 860 boats. During Operation Ariel, another 191,870 troops were rescued, bringing the total of military and civilian personnel returned to Britain during the Battle of France to 558,032, including 368,491 British troops.

In a war, sometimes the best thing that can be done is to retreat, but that is not always easy to do. When the enemy is closing in and there seems no way of escape. Sometimes, a way of escape seems to come together in such a way that it almost seems miraculous…or maybe that is the only real explanation…a miracle. Such seemed to be the case with Britain both in Dunkirk, France, called Operation Dynamo, and again from Cherbourg, Saint Malo, Brest, and Nantes, dubbed Operation Aerial. The evacuation from Dunkirk, was most likely the largest of its kind, or at least up to that date. I suppose there might have been others since then, but I am not aware of any. During the evacuation of Dunkirk, the British managed to evacuate 338,226 soldiers…and almost unheard of amount of men were saved, by a coordinated effort using 860 boats. During Operation Ariel, another 191,870 troops were rescued, bringing the total of military and civilian personnel returned to Britain during the Battle of France to 558,032, including 368,491 British troops.

Operation Aerial began on June 15, 1940 and ended on June 25, 1940. Following the military collapse in the Battle of France against Nazi Germany, it became evident that Allied soldiers and civilians were in grave danger. With two-thirds of France now occupied by German troops, those British and Allied troops that had not participated in Operation Dynamo, the evacuation of Dunkirk, were shipped home, but there remained a concern for the areas from Cherbourg, St. Malo, Brest, and Nantes. While these men were not under the immediate threat of assault, as at Dunkirk, they were by no means safe, so Brits, Poles, and Canadian troops were rescued from occupied territory by boats sent from Britain. Meanwhile, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill offered words of encouragement in a broadcast to the nation, “Whatever has happened in France…we shall defend our island home, and with the British Empire we shall fight on unconquerable until the curse of Hitler is lifted.” This was his way of promising that Britain would never fall under Nazi rule.

Operation Aerial was split into two sectors. Admiral James, based at Portsmouth, was to control the evacuation from Cherbourg and St Malo, while Admiral Dunbar-Nasmith, the commander-in-chief of the Western Approaches, based at Plymouth, would control the evacuation from Brest, St. Nazaire and La Pallice. Eventually this western evacuation would extend to include the ports on the Gironde estuary, Bayonne and St Jean-de-Luz. Once the people were on board, I’m sure they thought they were finally safe, but that was not necessarily the case. The Germans attacked the rescue boats. Among those rescued from the shores of France, were 5,000 soldiers and French civilians on board the ocean liner Lancastria, which had picked them up at St. Nazaire. Germans bombers sunk the liner on June 17, 1940, and 3,000 passengers drowned. Churchill ordered that news of the Lancastria not be broadcast in Britain, fearing the effect it would have on public morale, since everyone was already worried about a possible German invasion now that only a channel separated them. The British public would eventually find out, but not for another six weeks, when the news broke in the United States. They would also receive the good news that Hitler had no immediate plans for an invasion of the British isle, “being well aware of the difficulties involved in such an operation,” reported the German High Command.

In the end, the evacuations dubbed Operation Dynamo and Operation Aerial, were successful, in that most of those who were evacuated made it home. I’m sure that the retreats did not feel like a success or a victory to the soldiers fighting in the Battle of France, but I am also sure that they were thankful to be among those who made it home. They would live to fight another day in the horrendous war that was World War II.

In any wartime situation, there always seem to be those who think the United States should not get involved…mostly because they think that if we just stay out of it, the enemy will leave us alone. Of course, history does not prove that theory. When we look at the wars that the United States has been drawn into, only after we were attacked too, we find that the enemy always intended to take on the United States too, and we were only delaying the inevitable. It seems like every wartime president has had to deal with the naysayers, and President Eisenhower was no different. During the Cold War years when the Communists were trying to take over the world, Eisenhower chose a strong United States defense against it, but his view of a strong defense was much different that General Hoyt Vandenberg’s view. Vandenberg wanted a massive increase in conventional land, air, and sea forces, while Eisenhower said that a cheaper and more efficient defense could be built around the nation’s nuclear arsenal. Senator Robert Taft argued that if efforts to reach a peace agreement in Korea failed, the United States should withdraw from the United Nations forces and make its own policy for dealing with North Korea, basically a completely independent foreign policy, or what one “might call the ‘fortress’ theory of defense.” While both of these suggestions might seem like the best course of action, history tells us that Senator Taft’s suggestion would make us look weak, and possibility bring about attacks on the United States, and while I would tend to agree with General Vandenberg, that we need a strong defense system, I also understand that as technology changes, nations must change with it. Having hundreds of fighter planes is not necessary, if a few can drop a bomb that will settle the matter once and for all. It is similar to the use of pen and paper when we live in a computer age.

In any wartime situation, there always seem to be those who think the United States should not get involved…mostly because they think that if we just stay out of it, the enemy will leave us alone. Of course, history does not prove that theory. When we look at the wars that the United States has been drawn into, only after we were attacked too, we find that the enemy always intended to take on the United States too, and we were only delaying the inevitable. It seems like every wartime president has had to deal with the naysayers, and President Eisenhower was no different. During the Cold War years when the Communists were trying to take over the world, Eisenhower chose a strong United States defense against it, but his view of a strong defense was much different that General Hoyt Vandenberg’s view. Vandenberg wanted a massive increase in conventional land, air, and sea forces, while Eisenhower said that a cheaper and more efficient defense could be built around the nation’s nuclear arsenal. Senator Robert Taft argued that if efforts to reach a peace agreement in Korea failed, the United States should withdraw from the United Nations forces and make its own policy for dealing with North Korea, basically a completely independent foreign policy, or what one “might call the ‘fortress’ theory of defense.” While both of these suggestions might seem like the best course of action, history tells us that Senator Taft’s suggestion would make us look weak, and possibility bring about attacks on the United States, and while I would tend to agree with General Vandenberg, that we need a strong defense system, I also understand that as technology changes, nations must change with it. Having hundreds of fighter planes is not necessary, if a few can drop a bomb that will settle the matter once and for all. It is similar to the use of pen and paper when we live in a computer age.

President Eisenhower was no stranger to sending the military might of the United States out to attack the enemy, and in his days as a general, he made those decisions every day, but as every one should realize, the  more men you have to send, the more possibility of losing them. The decision to send soldiers to their deaths was not one that Eisenhower ever took lightly. With a strong nuclear arsenal, the enemy nation knew that they had better think twice before taking on the United States.

more men you have to send, the more possibility of losing them. The decision to send soldiers to their deaths was not one that Eisenhower ever took lightly. With a strong nuclear arsenal, the enemy nation knew that they had better think twice before taking on the United States.

Without naming either man, President Eisenhower responded to both during a speech at the National Junior Chamber of Commerce meeting in Minneapolis. His forceful speech struck back at critics of his Cold War foreign policy. He insisted that the United States was committed to the worldwide battle against communism and that he would maintain a strong United States defense. It was just a few months into his presidency, and the Korean War still raging, but Eisenhower laid out his basic approach to foreign policy with this speech. He began by characterizing the Cold War as a battle “for the soul of man himself.” He rejected Taft’s idea that the United States should pursue isolationism, and instead he insisted that all free nations had to stand together saying, “There is no such thing as partial unity.” To Vandenberg’s criticisms of the new Air Force budget, in which the president proposed a $5 billion cut from the Air Force budget, Eisenhower explained that vast numbers of aircraft were not needed in the new atomic age. Just a few planes armed with nuclear weapons could “visit on an enemy as much explosive violence as was hurled against Germany by our entire air effort throughout four years of World War II.” With this speech, Eisenhower thus pointed out the two major points of what came to be known at the time as his “New Look” foreign policy. First was his advocacy of multi-nation responses to communist aggression in preference to unilateral action by the United States. Second was the idea that came to be known as the “bigger bang for the buck” defense strategy.

Anytime a nation is facing war, it is a stressful time for its people, but no nation will do well using the isolation strategy, because a nation that appears to be weak in its own defense, will ultimately become a target for attack. I am not an advocate for the United Nations, and in fact, I believe we need to disband the United Nations, but I do believe that a nation must have allies…nations with like values, who are willing to go to war to back up their allies, and that we must not allow bully nations to take over smaller nations, because that only strengthens their resolve to expand further. I also believe that when technology becomes available, it must be properly combined with human forces to achieve the best result in the most efficient way.

Anytime a nation is facing war, it is a stressful time for its people, but no nation will do well using the isolation strategy, because a nation that appears to be weak in its own defense, will ultimately become a target for attack. I am not an advocate for the United Nations, and in fact, I believe we need to disband the United Nations, but I do believe that a nation must have allies…nations with like values, who are willing to go to war to back up their allies, and that we must not allow bully nations to take over smaller nations, because that only strengthens their resolve to expand further. I also believe that when technology becomes available, it must be properly combined with human forces to achieve the best result in the most efficient way.

A declaration of war usually means that the people in both areas within the dispute had better prepare for eminent attack, because the declaration of war is like firing the warning shot before the actual open-fire begins. Of course, it may not be an immediate attack, but the attack always comes…or does it. On September 3, 1939, the United Kingdom and France declared war on Nazi Germany, after the Germans invaded Poland. Over the next eight months, at the start of World War II, there were no major military land operations on the Western Front. Strange, considering that the United Kingdom and France had declared war on Nazi Germany. You would think that they would attack or something, but nothing happened. During those eight months, Poland was overrun. It took about five weeks for the German Invasion of Poland beginning September 1, 1939 and the Soviet invasion beginning on 17 September 1939. Still, the Western Allies did nothing. I guess I don’t understand that. War had been declared by each side, but no Western power would

A declaration of war usually means that the people in both areas within the dispute had better prepare for eminent attack, because the declaration of war is like firing the warning shot before the actual open-fire begins. Of course, it may not be an immediate attack, but the attack always comes…or does it. On September 3, 1939, the United Kingdom and France declared war on Nazi Germany, after the Germans invaded Poland. Over the next eight months, at the start of World War II, there were no major military land operations on the Western Front. Strange, considering that the United Kingdom and France had declared war on Nazi Germany. You would think that they would attack or something, but nothing happened. During those eight months, Poland was overrun. It took about five weeks for the German Invasion of Poland beginning September 1, 1939 and the Soviet invasion beginning on 17 September 1939. Still, the Western Allies did nothing. I guess I don’t understand that. War had been declared by each side, but no Western power would  launch a significant land offensive…even though the terms of the Anglo-Polish and Franco-Polish military alliances obligated the United Kingdom and France to assist Poland. They simply stood by and let it happen.

launch a significant land offensive…even though the terms of the Anglo-Polish and Franco-Polish military alliances obligated the United Kingdom and France to assist Poland. They simply stood by and let it happen.

The quiet of the so-named Phoney War was marked by a few Allied actions. During the Saar Offensive in September, France attacked Germany with the intention of assisting Poland, but the attack fizzled out within days and the French withdrew. In November, the Soviets attacked Finland in the Winter War. This resulted in much debate in France and Britain about helping Finland, but this campaign was delayed until the Winter War ended in March. The Allied discussions about a Scandinavian campaign caused concern in Germany and resulted in the German invasion of Denmark and Norway in April. Then the Allied troops that were previously assembled for Finland were redirected to Norway instead. Fighting there continued until June when the Allies evacuated, ceding Norway to Germany in response to the German invasion of France, which had taken place on May 10, 1940.

The Germans launched attacks at sea during the autumn and winter of 1939, against British aircraft carriers and destroyers, sinking several including the carrier HMS Courageous with the loss of 519 lives. Action in the air began on October 16, 1939 when the Luftwaffe launched air raids on British warships. There were various minor bombing raids and reconnaissance flights on both sides, but nothing that could possibly be viewed as a clear offensive….and during that whole time, people were dying and being subjected to various atrocities, because no one would help. Yes, war was declared, but it was a phony war, and apparently a phony declaration.

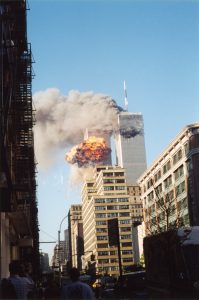

May 30, 2002 dawned, a typically warm New York City day, but this was not a typical day at all. It had been a long, emotionally grueling 8 months and 19 days of cleanup after the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and the crash site in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. The majority of the lost were in the World Trade Center in New York City. Those 8 months and 19 days were filled with every possible emotion there could be…from joy when one was found alive, to grief over the lost, to anger at the attack, to hate for the Muslim attackers, to love for the survivors and the families of the lost. It was something that we all knew that we could never really wrap our heads around, and something that we knew we would never forget. It was a senseless attack that proved only that the attackers were insane and filled with hate for Americans and Christians. It was a time when America came together as one, and donated time, money, letters, and love to each other, because we were all victims of this attack, after all.

May 30, 2002 dawned, a typically warm New York City day, but this was not a typical day at all. It had been a long, emotionally grueling 8 months and 19 days of cleanup after the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and the crash site in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. The majority of the lost were in the World Trade Center in New York City. Those 8 months and 19 days were filled with every possible emotion there could be…from joy when one was found alive, to grief over the lost, to anger at the attack, to hate for the Muslim attackers, to love for the survivors and the families of the lost. It was something that we all knew that we could never really wrap our heads around, and something that we knew we would never forget. It was a senseless attack that proved only that the attackers were insane and filled with hate for Americans and Christians. It was a time when America came together as one, and donated time, money, letters, and love to each other, because we were all victims of this attack, after all.

On May 29, 2002, the last beam was removed from the site…marking the end of the cleanup effort that had been expected to last a year. There were many disappointments in the cleanup, because there were very few people pulled out alive after that first day, and in fact, the last survivor was pulled out 27 hours after the attack. There would be no more lives saved. People were lined up to donate blood in the hope that someone’s life could be saved, but the sad reality was that very few whole bodies were even pulled from the rubble. Most were bits and pieces, body parts, and even just fragments of bone or teeth. Authorities put the final death toll from the World Trade Center’s destruction at 2,823. Of those 2823 people, only 1,102 victims have been identified, and only 289 intact bodies were recovered.

The ceremony…if it could really be called that, because ceremony usually means a happy event…began in silence. There would be no speeches. Thousands of people stood silently in one place…Ground Zero, and no one spoke…no one spoke!! The ceremony began with the sound of a fire bell ringing for the fallen firefighters at 10:29 am ET, the same time the World Trade Center’s north tower collapsed on September 11, 2001. Thousands of people stood in silence, some with tears streaming from their eyes, as an honor guard made up of police, firefighters, and representatives of other agencies walked slowly up a ramp from the site carrying a stretcher bearing only an American flag. The flag, symbolizing the victims who were killed on September 11, but never found, was placed into a waiting ambulance. It was followed by a flatbed truck carrying the last 50 ton steel column from the site of the Trade Center ruins. The beam was part of the southeast corner of the south tower. It was hoisted onto a flatbed truck and shrouded in black cloth after its removal on May 29, 2002. Ten minutes into the ceremony, a pair of buglers…one from New York’s Police Department, the other from the New York Fire Department…played “Taps,” followed by a flyover of NYPD helicopters. Among the dead following the horrific attack, were 343 New York firefighters and an estimated 70 police officers from various departments, including 37 from New York’s Port Authority and 23 from the New York Police Department. Fewer than half of the firefighters who died were recovered. Five of them were from the Chelsea Firehouse, Engine 3 and Ladder 12. At the fire stations and police stations in New York City, dozens of family and friends watched the tribute on television. Hundreds of workers had labored around the clock since September 11 to recover the

bodies of those who died in the attack and to remove the 1.6 million tons of steel and concrete left behind. The debris was moved to a Staten Island landfill, but reminders of the attack remain in the area. “It’s over, but it will never be forgotten,” said FDNY Battalion Commander Richard Picciotto, who was in the north tower when it was hit. He was right. Today marks the 15th anniversary of that ceremony, and we have not forgotten.

bodies of those who died in the attack and to remove the 1.6 million tons of steel and concrete left behind. The debris was moved to a Staten Island landfill, but reminders of the attack remain in the area. “It’s over, but it will never be forgotten,” said FDNY Battalion Commander Richard Picciotto, who was in the north tower when it was hit. He was right. Today marks the 15th anniversary of that ceremony, and we have not forgotten.

War is tough enough without having a traitor in the mix, and when a traitor is involved, things get even worse. One such traitor of World War II, was Mildred Gillars, aka Axis Sally. Apparently, Gillars, an American, was a opportunist. In 1940, she went to work as an announcer with the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft (RRG), German State Radio. At the time, I suppose that she did nothing wrong…up to that point. In 1941, the US State Department was advising American nationals to return home, but Gillars chose to remain because her fiancé, Paul Karlson, a naturalized German citizen, said he would never marry her if she returned to the United States. Then, Karlson was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was killed in action. Gillars still did not return home.

War is tough enough without having a traitor in the mix, and when a traitor is involved, things get even worse. One such traitor of World War II, was Mildred Gillars, aka Axis Sally. Apparently, Gillars, an American, was a opportunist. In 1940, she went to work as an announcer with the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft (RRG), German State Radio. At the time, I suppose that she did nothing wrong…up to that point. In 1941, the US State Department was advising American nationals to return home, but Gillars chose to remain because her fiancé, Paul Karlson, a naturalized German citizen, said he would never marry her if she returned to the United States. Then, Karlson was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was killed in action. Gillars still did not return home.

On December 7, 1941, Gillars was working in the studio when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was announced. She broke down in front of her colleagues and denounced their allies in the east. “I told them what I thought about Japan and that the Germans would soon find out about them,” she recalled. “The shock was terrific. I lost all discretion.” This may have been the the last time she had any self respect. She later said that she knew that her outburst could send her to a concentration camp, so faced with the prospect of joblessness or prison, the frightened Gillars produced a written oath of allegiance to Germany and returned to work. She sold out. Her duties were initially limited to announcing records and participating in chat shows, but treason is a slippery slope. Gillars’ broadcasts initially were largely apolitical, but that changed in 1942, when Max Otto Koischwitz, the program director in the USA Zone at the RRG, cast Gillars in a new show called Home Sweet Home. She soon acquired several names amongst her GI audience, including the Berlin Bitch, Berlin Babe, Olga, and Sally, but the one most common was “Axis Sally”. This name probably came when asked on air to describe herself, Gillars had said she was “the Irish type… a real Sally.”

As her broadcasts progressed, Gillars began doing a show called Home Sweet Home Hour. This show ran from December 24, 1942, until 1945. It was a regular propaganda program, the purpose of which was to make US forces in Europe feel homesick. A running theme of these broadcasts was the infidelity of soldiers’ wives and sweethearts while the listeners were stationed in Europe and North Africa. I’m was designed to promote depression. I guess her aversion to the ways of the Japanese and Germans wasn’t so strong after all. She also did a show called Midge-at-the-Mike, which broadcast from March to late fall 1943. I this program, she played American songs interspersed with defeatist propaganda, anti-Semitic rhetoric and attacks on Franklin D. Roosevelt. And she did the GI’s Letter-box and Medical Reports 1944, which was directed at the US home audience. In this show, Gillars used information on wounded and captured US airmen to cause fear and worry in their families. After D-Day, June 6, 1944, US soldiers wounded and captured in France were also reported on. Gillars and Koischwitz worked for a time from Chartres and Paris for this purpose, visiting hospitals and interviewing POWs. In 1943 they had toured POW camps in Germany, interviewing captured Americans and recording their messages for their families in the US. The interviews were then edited for broadcast as though the speakers were well-treated or sympathetic to the Nazi cause. Gillars made her most notorious broadcast on June 5, 1944, just prior to the D-Day invasion of Normandy, France, in a radio play written by Koischwitz, Vision Of Invasion. She played Evelyn, an Ohio mother, who dreams that her son had died a horrific death on a ship in the English Channel during an attempted invasion of Occupied Europe.

After the war, Gillars mingled with the people of Germany, until her capture. Gillars was indicted on September 10, 1948, and charged with ten counts of treason, but only eight were proceeded with at her trial, which began  on January 25, 1949. The prosecution relied on the large number of her programs recorded by the FCC, stationed in Silver Hill, Maryland, to show her active participation in propaganda activities against the United States. It was also shown that she had taken an oath of allegiance to Hitler. The defense argued that her broadcasts stated unpopular opinions but did not amount to treasonable conduct. It was also argued that she was under the hypnotic influence of Koischwitz and therefore not fully responsible for her actions until after his death. On March 10, 1949, the jury convicted Gillars on just one count of treason, that of making the Vision Of Invasion broadcast. She was sentenced to 10 to 30 years in prison, and a $10,000 fine. In 1950, a federal appeals court upheld the sentence. She died June 25, 1988 at the age of 87.

on January 25, 1949. The prosecution relied on the large number of her programs recorded by the FCC, stationed in Silver Hill, Maryland, to show her active participation in propaganda activities against the United States. It was also shown that she had taken an oath of allegiance to Hitler. The defense argued that her broadcasts stated unpopular opinions but did not amount to treasonable conduct. It was also argued that she was under the hypnotic influence of Koischwitz and therefore not fully responsible for her actions until after his death. On March 10, 1949, the jury convicted Gillars on just one count of treason, that of making the Vision Of Invasion broadcast. She was sentenced to 10 to 30 years in prison, and a $10,000 fine. In 1950, a federal appeals court upheld the sentence. She died June 25, 1988 at the age of 87.