Politics

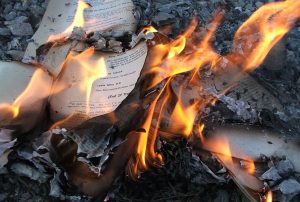

Book burning is the ritual destruction by fire of books or other written materials. This practice is usually carried out in a public place, so as to further destroy any sense of control of one’s own life. The burning of books represents an element of censorship and usually proceeds from a cultural, religious, or political opposition to the materials in question. Sometimes those burning the books think they are “protecting” the people from something they deem to be evil, but more often, the books simply don’t agree with the agenda of the controlling group. Such was the case with the most famous book burning, which took place under the Nazi regime on May 10, 1933. The May 1933 book burning in Nazi Germany was preceded in nineteenth century Germany. In 1817, German student associations (Burschenschaften) chose the 300th anniversary of Luther’s 95 Theses to hold a festival at the Wartburg, a castle in Thuringia where Luther had sought sanctuary after his excommunication. The students were demonstrating for a unified country. Germany was then a patchwork of states. During the protest, the students burned anti-national and reactionary texts and literature which the students viewed as “Un-German” in nature or content. I wonder if they had any idea that the freedom to protest was the very thing they were looking to take away in the future Germany.

Book burning is the ritual destruction by fire of books or other written materials. This practice is usually carried out in a public place, so as to further destroy any sense of control of one’s own life. The burning of books represents an element of censorship and usually proceeds from a cultural, religious, or political opposition to the materials in question. Sometimes those burning the books think they are “protecting” the people from something they deem to be evil, but more often, the books simply don’t agree with the agenda of the controlling group. Such was the case with the most famous book burning, which took place under the Nazi regime on May 10, 1933. The May 1933 book burning in Nazi Germany was preceded in nineteenth century Germany. In 1817, German student associations (Burschenschaften) chose the 300th anniversary of Luther’s 95 Theses to hold a festival at the Wartburg, a castle in Thuringia where Luther had sought sanctuary after his excommunication. The students were demonstrating for a unified country. Germany was then a patchwork of states. During the protest, the students burned anti-national and reactionary texts and literature which the students viewed as “Un-German” in nature or content. I wonder if they had any idea that the freedom to protest was the very thing they were looking to take away in the future Germany.

Then, in 1933, Nazi German authorities, decided to synchronize professional and cultural organizations with Nazi ideology and policy (Gleichschaltung). Nazi Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, spearheaded an effort to bring German arts and culture in line with Nazi goals. The government began to remove cultural organizations of Jewish and other officials who were alleged to be politically suspect or who performed or created art works which Nazi ideologues labeled “degenerate.” Goebbels also had a strong ally in the National Socialist German Students’ Association (Nationalsozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund), so he used them to bring the literary phase into being. German university students were at the forefront of the early Nazi movement, and in the late 1920s. Many of them filled the ranks of various Nazi formations. The ultra-nationalism and antisemitism of middle-class, secular student organizations had been intense and vocal for decades. After World War I, many students opposed the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and found in National Socialism a suitable vehicle for their political discontent and hostility.

On April 6, 1933, the Nazi German Student Association’s Main Office for Press and Propaganda proclaimed a nationwide “Action against the Un-German Spirit,” to end in a literary purge or “cleansing” (Säuberung) by fire. Local chapters were to supply the press with releases and commissioned articles, offer blacklists of “un-German” authors, sponsor well-known Nazi figures to speak at public gatherings, and negotiate for radio broadcast time. Then, in a symbolic act of ominous significance, on May 10, 1933, university students burned upwards of 25,000 volumes of “un-German” books, presaging an era of state censorship and control of culture. On the evening of May 10, in most university towns, right-wing students marched in torchlight parades “against the un-German spirit.” The scripted rituals called for high Nazi officials, professors, university rectors, and university student leaders to address the participants and spectators. In Berlin, some 40,000 persons gathered  in the Opernplatz to hear Joseph Goebbels delivered a fiery address: “No to decadence and moral corruption!” He went on to say, “Yes to decency and morality in family and state! I consign to the flames the writings of Heinrich Mann, Ernst Gläser, Erich Kästner.” Among the authors whose books student leaders burned that night were well-known socialists such as Bertolt Brecht and August Bebel; the founder of the concept of communism, Karl Marx; critical “bourgeois” writers like the Austrian playwright Arthur Schnitzler; and “corrupting foreign influences,” among them American author Ernest Hemingway. I don’t agree with some of these writings, but I also don’t agree with their destruction. People can make up their own minds.

in the Opernplatz to hear Joseph Goebbels delivered a fiery address: “No to decadence and moral corruption!” He went on to say, “Yes to decency and morality in family and state! I consign to the flames the writings of Heinrich Mann, Ernst Gläser, Erich Kästner.” Among the authors whose books student leaders burned that night were well-known socialists such as Bertolt Brecht and August Bebel; the founder of the concept of communism, Karl Marx; critical “bourgeois” writers like the Austrian playwright Arthur Schnitzler; and “corrupting foreign influences,” among them American author Ernest Hemingway. I don’t agree with some of these writings, but I also don’t agree with their destruction. People can make up their own minds.

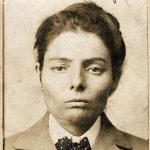

Stagecoach drivers like Charley Parkhurst were tough as nails. Not everyone could handle a stagecoach. The stagecoach driver was respected…sometimes even more than was the millionaire statesman who might be riding beside him, or anyone else who had been given that honor. Parkhurst had been through the good times and bad times of driving stagecoach. Twice, Charley was held up. The first time, he was forced to throw down his strongbox because he was unarmed. The second time, he was prepared. When a road agent ordered the stage to stop and commanded Charley to throw down its strongbox, Parkhurst leveled a shotgun blast into the chest of the outlaw, whipped his horses into a full gallop, and left the bandit in the road.

Stagecoach drivers like Charley Parkhurst were tough as nails. Not everyone could handle a stagecoach. The stagecoach driver was respected…sometimes even more than was the millionaire statesman who might be riding beside him, or anyone else who had been given that honor. Parkhurst had been through the good times and bad times of driving stagecoach. Twice, Charley was held up. The first time, he was forced to throw down his strongbox because he was unarmed. The second time, he was prepared. When a road agent ordered the stage to stop and commanded Charley to throw down its strongbox, Parkhurst leveled a shotgun blast into the chest of the outlaw, whipped his horses into a full gallop, and left the bandit in the road.

Charley Parkhurst was one of the more skillful stagecoach drivers, not only in  California, but throughout the west. He was often called “One-eyed” or “Cockeyed” Charley, because he had lost an eye when kicked by a horse. He drove a stagecoach in California for 20 years. One-eyed Charley was known as one of the toughest, roughest, and the most daring of all stagecoach drivers. Like most drivers, he was proud of his skill in the extremely difficult job as “whip.” A “whip” is what stagecoach drivers were often called. Proper handling of the horses and the great coaches was an art that required much practice, experience, and not the least, courage. Whips received high salaries for the times, sometimes as much as $125 a month, plus room and board. While most stage drivers were sober, at least while on duty, nearly all were fond of an occasional “eye opener.” A good driver was the captain of his craft. His timid passengers feared him. He was

California, but throughout the west. He was often called “One-eyed” or “Cockeyed” Charley, because he had lost an eye when kicked by a horse. He drove a stagecoach in California for 20 years. One-eyed Charley was known as one of the toughest, roughest, and the most daring of all stagecoach drivers. Like most drivers, he was proud of his skill in the extremely difficult job as “whip.” A “whip” is what stagecoach drivers were often called. Proper handling of the horses and the great coaches was an art that required much practice, experience, and not the least, courage. Whips received high salaries for the times, sometimes as much as $125 a month, plus room and board. While most stage drivers were sober, at least while on duty, nearly all were fond of an occasional “eye opener.” A good driver was the captain of his craft. His timid passengers feared him. He was  held in awe by stable boys, and was the trusty agent of his employer…and Charley was the best.

held in awe by stable boys, and was the trusty agent of his employer…and Charley was the best.

Nevertheless, little was really known about Charley Parkhurst before or after he came to California. It wasn’t until his body was prepared for burial that his true secret was discovered. Charlotte “Charley” Parkhurst was a woman. One doctor claimed that at some point in her life, she had been a mother. Unknowingly, Parkhurst could claim a national first. After voting on Election Day, November 3, 1868, Charley was probably the first woman to cast a ballot in any election. It wasn’t until 52 years later that the right to vote was guaranteed to women by the nineteenth amendment.

With new technology, always comes some risk of failure. Sometimes, the the failure doesn’t hurt anything, but other times, it can be deadly. In the world of submarines, the atomic submarine was the latest thing in the 1960s. The USS Thresher was launched on July 9, 1960, from Portsmouth Naval Yard in New Hampshire. It was built with the latest technology, and was the first submarine assembled as part of a new class that could run more quietly and dive deeper than any that had come before it. The designers and the Navy expected great things from Thresher, and initially, the submarine met their expectations.

With new technology, always comes some risk of failure. Sometimes, the the failure doesn’t hurt anything, but other times, it can be deadly. In the world of submarines, the atomic submarine was the latest thing in the 1960s. The USS Thresher was launched on July 9, 1960, from Portsmouth Naval Yard in New Hampshire. It was built with the latest technology, and was the first submarine assembled as part of a new class that could run more quietly and dive deeper than any that had come before it. The designers and the Navy expected great things from Thresher, and initially, the submarine met their expectations.

Then on April 10, 1963, at just before 8am, the Thresher was conducting drills off the coast of Cape Cod. At 9:13am, the USS Skylark, another ship participating in the drills, received a communication from the Thresher that the sub was experiencing  minor problems. Unfortunately, the minor problems turned into a very major problem…almost instantly. Other attempted communications with Thresher failed and, only five minutes later, sonar images showed the Thresher breaking apart as it fell to the bottom of the sea, 300 miles off the coast of New England. Sixteen officers, 96 sailors and 17 civilians were on board. All were killed.

minor problems. Unfortunately, the minor problems turned into a very major problem…almost instantly. Other attempted communications with Thresher failed and, only five minutes later, sonar images showed the Thresher breaking apart as it fell to the bottom of the sea, 300 miles off the coast of New England. Sixteen officers, 96 sailors and 17 civilians were on board. All were killed.

On April 12, President John F. Kennedy ordered that flags across the country be flown at half-staff to commemorate the lives lost in this disaster. A subsequent investigation revealed that a leak in a silver-brazed joint in the engine room had caused a short circuit in critical electrical systems. The problems quickly spread, making the equipment needed to bring the Thresher to the surface inoperable. The submarine went into a freefall to the bottom. There was no time to do anything to stop it or find a way of escape…if one existed.

The disaster forced improvements in the design and quality control of submarines. Twenty-five years later, in 1988, Vice Admiral Bruce Demars, the Navy’s chief submarine officer, said “The loss of Thresher initiated fundamental changes in the way we do business–changes in design, construction, inspections, safety checks, tests, and more. We have not forgotten the lessons learned. It’s a much safer submarine force today.” I don’t think there was necessarily anything that was done so wrong that it could have prevented what happened, but I could be wrong. Obviously, there is always room for improvement in any design, but unfortunately, sometimes the only way to know that an improvement is needed, is to have a disaster strike.

During the Vietnam War, as in any war, children can become displaced because of the loss of their parents. The country has already lost so many people, and often there is no one to take these little orphans, so they often end up in an orphanage, waiting for someone to come along and adopt them. Many times, they live their entire childhood in that orphanage. For a country that has already be devastated by war, the cost of raising these children is detrimental. Such was the case for orphaned children from the Vietnam War. Then the United States made the decision to airlift these children to the United States to be adopted by American families who were waiting for children. The plan was dubbed Operation Baby Lift, and while it would end up being successful, it got of the a sad and rocky start on April 4, 1975, when the first plane crashed shortly after taking off from Tan Son Nhut airbase in Saigon. On board were more than 300 passengers. Of those, 138 passengers, mostly children were killed.

During the Vietnam War, as in any war, children can become displaced because of the loss of their parents. The country has already lost so many people, and often there is no one to take these little orphans, so they often end up in an orphanage, waiting for someone to come along and adopt them. Many times, they live their entire childhood in that orphanage. For a country that has already be devastated by war, the cost of raising these children is detrimental. Such was the case for orphaned children from the Vietnam War. Then the United States made the decision to airlift these children to the United States to be adopted by American families who were waiting for children. The plan was dubbed Operation Baby Lift, and while it would end up being successful, it got of the a sad and rocky start on April 4, 1975, when the first plane crashed shortly after taking off from Tan Son Nhut airbase in Saigon. On board were more than 300 passengers. Of those, 138 passengers, mostly children were killed.

Captain Dennis “Bud” Traynor was the captain on the plane. Many of the 138 passengers were children, and  many of them were under age 2 and so small, they had to be carried onto the plane. “We bucket-brigade-loaded the children right up the stairs into the airplane,” Traynor remembers. The flight began normally, but shortly into the flight, when the plane’s cargo doors malfunctioned they blew out, taking with them a chunk of the tail. There was a rapid decompression inside the aircraft, causing the pilot, Traynor, to crash land the C-5 cargo plane into a nearby rice paddy. Traynor managed to stabilize the plane and turn it back toward Vietnam. After that, his only option was a crash landing. The impact was fierce. “It cut all control cables to the tail,” explains Traynor. “So I’m pulling and pulling and pulling, and my nose is going down further and further and we’re going faster and faster and faster, and I can’t figure this out. We came to a stop and I thought to myself ‘I’m alive,'” he says. “And so I undid my lap belt, fell to the ceiling, rolled open the side window, and stepped out and saw the wings burning. And I thought, ‘Oh no, that’s the rest of the airplane.'” Out of the more than 300 people on board, the death toll included 78 children and about 50 adults, including Air Force personnel. More than 170 survived.

many of them were under age 2 and so small, they had to be carried onto the plane. “We bucket-brigade-loaded the children right up the stairs into the airplane,” Traynor remembers. The flight began normally, but shortly into the flight, when the plane’s cargo doors malfunctioned they blew out, taking with them a chunk of the tail. There was a rapid decompression inside the aircraft, causing the pilot, Traynor, to crash land the C-5 cargo plane into a nearby rice paddy. Traynor managed to stabilize the plane and turn it back toward Vietnam. After that, his only option was a crash landing. The impact was fierce. “It cut all control cables to the tail,” explains Traynor. “So I’m pulling and pulling and pulling, and my nose is going down further and further and we’re going faster and faster and faster, and I can’t figure this out. We came to a stop and I thought to myself ‘I’m alive,'” he says. “And so I undid my lap belt, fell to the ceiling, rolled open the side window, and stepped out and saw the wings burning. And I thought, ‘Oh no, that’s the rest of the airplane.'” Out of the more than 300 people on board, the death toll included 78 children and about 50 adults, including Air Force personnel. More than 170 survived.

While it was an unusual plan, hatched in the midst of the political fallout, the United States government announced the plan to get thousands of displaced Vietnamese children out of the country. President Ford directed that money from a special foreign aid children’s fund be made available to fly 2,000 South Vietnamese orphans to the United States. Operation Baby Lift lasted for just ten days. Baby Lift was carried out during the final, desperate phase of the war, as North Vietnamese forces closed in on Saigon. Although this first flight ended in tragedy, the rest of the flights were completed safely, and Baby Lift aircraft brought orphans across the Pacific until the mission’s conclusion on April 14, just 16 days before the fall of Saigon and the end of the war.

While it was an unusual plan, hatched in the midst of the political fallout, the United States government announced the plan to get thousands of displaced Vietnamese children out of the country. President Ford directed that money from a special foreign aid children’s fund be made available to fly 2,000 South Vietnamese orphans to the United States. Operation Baby Lift lasted for just ten days. Baby Lift was carried out during the final, desperate phase of the war, as North Vietnamese forces closed in on Saigon. Although this first flight ended in tragedy, the rest of the flights were completed safely, and Baby Lift aircraft brought orphans across the Pacific until the mission’s conclusion on April 14, just 16 days before the fall of Saigon and the end of the war.

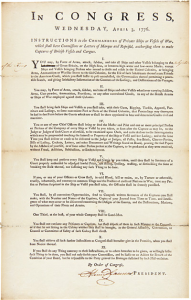

When the United States, still known as the colonies at that time, it lacked sufficient funds to build a strong navy, and with the coming Revolutionary War, they needed that strength. So, the Continental Congress gave privateers permission to attack any and all British ships. What is a privateer, you might ask? A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war.

When the United States, still known as the colonies at that time, it lacked sufficient funds to build a strong navy, and with the coming Revolutionary War, they needed that strength. So, the Continental Congress gave privateers permission to attack any and all British ships. What is a privateer, you might ask? A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war.

In a bill signed by John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, and dated April 3, 1776, the Continental Congress issued, “INSTRUCTIONS to the COMMANDERS of Private Ships or vessels of War, which shall have Commissions of Letters of Marque and Reprisal, authorizing them to make Captures of British Vessels and Cargoes.” Letters of Marque and Reprisal were the official documents by which 18th century governments commissioned private commercial ships, known as privateers, to act on their behalf, attacking ships carrying the flags of enemy nations. As a perk, any goods captured by the privateer were divided between the ship’s owner and the government that had issued the letter.

Congress informed American privateers on this day that, “YOU may, by Force of Arms, attack, subdue, and take all Ships and other Vessels belonging to the Inhabitants of Great Britain, on the high seas, or between high-water and low-water Marks, except Ships and Vessels bringing Persons who intend to settle and reside in the United Colonies, or bringing Arms, Ammunition or Warlike Stores to the said Colonies, for the Use of such Inhabitants thereof as are Friends to the American Cause, which you shall suffer to pass unmolested, the Commanders thereof permitting a peaceable Search, and giving satisfactory Information of the Contents of the Ladings, and Destinations of the Voyages.” In many ways, this action was very similar to guerrilla warfare, except it was a battle fought on the high seas, and unlike guerrillas, these men were acting under the authority of the government…even if both were fighting for their nation.

For those who faced them on the high seas, there was no difference between pirates and privateers. They  acted and operated identically, boarding and capturing ships using force, if necessary. However, privateers holding Letters of Marque were not subject to prosecution by their home nation and, if captured, were treated as prisoners of war instead of criminals by foreign nations. I wonder if their were actually pirates among he privateers. To me, it would make sense to believe that their were, but perhaps the government would not authorize known pirates to do this work. Either way, the privateer commission was a very successful form of warfare in the Revolutionary War days.

acted and operated identically, boarding and capturing ships using force, if necessary. However, privateers holding Letters of Marque were not subject to prosecution by their home nation and, if captured, were treated as prisoners of war instead of criminals by foreign nations. I wonder if their were actually pirates among he privateers. To me, it would make sense to believe that their were, but perhaps the government would not authorize known pirates to do this work. Either way, the privateer commission was a very successful form of warfare in the Revolutionary War days.

Over the course of our nation’s history, we have managed to keep most of our presidents safe. Out of 45 Presidents of the United States, 4 were assassinated, and 6 others were shot while in office, but survived their attacks. Ronald Regan was the last United States President to be shot while in office. Reagan did not immediately realize that he had been shot…something that came as a shock to many. He was rushed to the hospital, where he underwent emergency surgery to remove the bullet and to repair his lung. The president remained in good humor, and he reportedly told his wife Nancy, “Honey, I forgot to duck” (a line first attributed to the boxing heavyweight Jack Dempsey when he lost the title to Gene Tunney in 1926), and to his doctors he said, “Please tell me you’re Republicans.” He was a loyal Conservative all his life.

Over the course of our nation’s history, we have managed to keep most of our presidents safe. Out of 45 Presidents of the United States, 4 were assassinated, and 6 others were shot while in office, but survived their attacks. Ronald Regan was the last United States President to be shot while in office. Reagan did not immediately realize that he had been shot…something that came as a shock to many. He was rushed to the hospital, where he underwent emergency surgery to remove the bullet and to repair his lung. The president remained in good humor, and he reportedly told his wife Nancy, “Honey, I forgot to duck” (a line first attributed to the boxing heavyweight Jack Dempsey when he lost the title to Gene Tunney in 1926), and to his doctors he said, “Please tell me you’re Republicans.” He was a loyal Conservative all his life.

John Hinckley, Jr. was a deranged individual with a crazed obsession for Jody Foster. Hinckley’s path toward the assassination attempt began in 1976 when he saw the movie Taxi Driver. In the movie, Robert DeNiro’s character, Travis Bickle stalks a Presidential candidate in the hopes that he will somehow impress and rescue a young prostitute played by Jodie Foster. Hinckley, who spent seven years in college without earning a degree or making a friend, added Foster to his list of obsessions, which also included Nazis, the Beatles, and assassins. In May 1980, Hinckley wrote to Foster while she attended Yale University, traveled there and talked to her on the phone at least once. Soon after, he began following President Jimmy Carter. In October, he was arrested at airport near a Carter campaign stop for carrying guns. However, the Secret Service was not notified. Hinckley  simply went to a pawnshop in Dallas and bought more guns. For the next several months, Hinckley’s plans changed daily. He pondered kidnapping Foster, considered killing Senator Edward Kennedy and began stalking newly elected President Reagan. Finally, he wrote a letter to Foster explaining that his attempt on Reagan’s life was for her. He kept abreast of the president’s schedule by reading the newspaper.

simply went to a pawnshop in Dallas and bought more guns. For the next several months, Hinckley’s plans changed daily. He pondered kidnapping Foster, considered killing Senator Edward Kennedy and began stalking newly elected President Reagan. Finally, he wrote a letter to Foster explaining that his attempt on Reagan’s life was for her. He kept abreast of the president’s schedule by reading the newspaper.

On March 30, 1981, Hinckley decided that he had found the perfect opportunity, and it turns out that he was right. Normally the President wears a bullet proof vest when entering and exiting engagements, but as it was only 30 feet to the limo, it was deemed unnecessary. Bad idea. Reagan stepped outside the Hilton Hotel in Washington D.C. where he had just addressed the Building and Construction Workers Union of the AFL-CIO. Hinckley was armed with a .22 revolver with exploding bullets and was only ten feet away from Reagan when he began shooting. Fortunately, he was a poor shot and most of the bullets did not explode as they were supposed to. Hinckley’s first shot hit press secretary James Brady in the head, critically wounding him, and other shots wounded a police officer and a Secret Service agent. The final shot hit Reagan’s limo and then ricocheted into the President’s chest. Hinckley had completely missed  Reagan, but “got lucky” when the bullet ricocheted. How he managed that is beyond the imagination, and not so “lucky” for President Reagan who, as he said, “Forgot to duck.” I also find it amazing that President Reagan could keep his sense of humor. It shows me what a man of grit he really was.

Reagan, but “got lucky” when the bullet ricocheted. How he managed that is beyond the imagination, and not so “lucky” for President Reagan who, as he said, “Forgot to duck.” I also find it amazing that President Reagan could keep his sense of humor. It shows me what a man of grit he really was.

Hinckley was also wounded police officer Thomas Delahanty and Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy. All of the shooting victims survived, although Brady’s 2014 death was later ruled a homicide 33 years after he was shot. Hinckley was later not found not guilty by reason of insanity. Hinckley was released from institutional psychiatric care on September 10, 2016, which I find astonishing. He currently lives with his mother.

Seldom, if ever, do you see a minor political party that is able to obtain national support for their way of doing things, but that did happen in the 1920s. The Prohibition Party (PRO) is a political party in the United States best known for its historic opposition to the sale or consumption of alcoholic beverages. It is the oldest existing third party in the US. The party was an integral part of the temperance movement. I suppose it depends on which side you were on, as to how you feel about alcohol, but the reality is that they most likely didn’t have the support of the majority of the American citizens.

Seldom, if ever, do you see a minor political party that is able to obtain national support for their way of doing things, but that did happen in the 1920s. The Prohibition Party (PRO) is a political party in the United States best known for its historic opposition to the sale or consumption of alcoholic beverages. It is the oldest existing third party in the US. The party was an integral part of the temperance movement. I suppose it depends on which side you were on, as to how you feel about alcohol, but the reality is that they most likely didn’t have the support of the majority of the American citizens.

Nevertheless, on Saturday, January 7, 1920, the Manchester Guardian reported with a level of mild shock on one of the most extraordinary experiments in modern democratic history. “One minute after midnight tonight,” the story began, “America will become an entirely arid desert as far as alcoholics are concerned, any drinkable containing more than half of 1 per cent alcohol being forbidden.” In fact, the Volstead Act, which prohibited the sale of “intoxicating liquors,” had come into operation at midnight the day before. But the authorities had granted drinkers one last day, one last session at the bar, before the iron shutters of Prohibition came down.

I don’t really know how I feel about the comparison between the prohibition of alcohol, and the war on drugs (specifically Marijuana), but one thing can be said for sure. With the law that made these things illegal, came, by natural progression, the gangs or gangsters, who illegally made a way for those things to be obtained by the people. As to Prohibition, the 20s were filled with bootleggers, gangsters, and illegal purchases of alcohol…hence the Roaring Twenties.

Across the United States, many bars and restaurants marked the demise of the demon drink by handing out free glasses of wine, brandy and whisky. Others saw one last opportunity to make a killing, charging an eye-watering “20 to 30 dollars for a bottle of champagne, or a dollar to two dollars for a drink of whisky”. In some establishments, mournful dirges played while coffins were carried through the crowds of drinkers. In others, the walls were hung with black crepe. And in the most prestigious establishments, the Guardian noted, placards carried the ominous words: “Exit booze. Doors close on Saturday.” It was like an Irish wake for the deceased.

The prohibition of alcohol lasted for almost 14 years, and with it came a violent era in out country’s history. Gangsters like Al Capone, Bugsy Segal, Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Johnny Torrio, Arnold Rothstein, Bugs Moran, Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, and the mafia sprung into action…refusing to be railroaded. Prohibition’s largely Protestant champions, a large proportion of whom were high-minded, middle-class women. were the do-gooders of the day. Often deeply religious, they saw Prohibition as a kind of social reform, a crusade to clean up the American city and restore the founding virtues of the godly republic. The gangsters, gangs, and the mafia saw it as a declaration of war, and acted accordingly. Stills were built, and bootleggers financed.

Before long violence broke out as the runners were caught and the gangsters lost their product. Nevertheless, for 14 long years, Prohibition persisted, until there was finally enough pull in Congress. The 21st Amendment to the United States Constitution is ratified on December 5, 1933, repealing the 18th Amendment and bringing an end to the era of national prohibition of alcohol in America. At 5:32pm EST, Utah became the 36th state to ratify the amendment, achieving the requisite three-fourths majority of states’ approval. Pennsylvania and Ohio had ratified it earlier in the day.

Before long violence broke out as the runners were caught and the gangsters lost their product. Nevertheless, for 14 long years, Prohibition persisted, until there was finally enough pull in Congress. The 21st Amendment to the United States Constitution is ratified on December 5, 1933, repealing the 18th Amendment and bringing an end to the era of national prohibition of alcohol in America. At 5:32pm EST, Utah became the 36th state to ratify the amendment, achieving the requisite three-fourths majority of states’ approval. Pennsylvania and Ohio had ratified it earlier in the day.

When we think of our nation’s early wars, and really, up until the Persian Gulf War, soldiers were officially men only. Prior to the Persian Gulf War, any women who were in combat were disguised as men, or they were in non-combat roles, such as support staff and nurses. Few women were recognized for their service, much less honored for it, but on March 12, 1776, in Baltimore, Maryland, someone decided to change the way we looked at the effort made by women in wars. And when I say effort know that I include much sacrifice.

When we think of our nation’s early wars, and really, up until the Persian Gulf War, soldiers were officially men only. Prior to the Persian Gulf War, any women who were in combat were disguised as men, or they were in non-combat roles, such as support staff and nurses. Few women were recognized for their service, much less honored for it, but on March 12, 1776, in Baltimore, Maryland, someone decided to change the way we looked at the effort made by women in wars. And when I say effort know that I include much sacrifice.

That day, a public notice appeared in local papers recognizing the sacrifice of women to the cause of the revolution. The notice urged others to recognize women’s contributions as well, and announced, “The necessity of taking all imaginable care of those who may happen to be wounded in the country’s cause, urges us to address our humane ladies, to lend us their kind assistance in furnishing us with linen rags and old sheeting, for bandages.” On and off the battlefield, women were known to support the revolutionary cause by providing nursing assistance. But donating bandages and sometimes applying them was only one form of aid provided by the women of the new United States. From the earliest protests against British taxation, women’s assent and labor  was critical to the success of the cause. The boycotts that united the colonies against British taxation required female participation far more than male participation, in fact, the men designing the non-importation agreements chose to boycott products used mostly by women…how thoughtful of them!!

was critical to the success of the cause. The boycotts that united the colonies against British taxation required female participation far more than male participation, in fact, the men designing the non-importation agreements chose to boycott products used mostly by women…how thoughtful of them!!

Tea and cloth are perhaps the best examples of these boycotted products. While most schoolchildren have read of the men who dressed as Mohawk Indians and dumped large volumes of tea into Boston Harbor at the Boston Tea Party, as a form of opposition to the hated Tea Act, few realize that women…not men…drank most of the tea in colonial America. Samuel Adams and his friends may have dumped the tea in the harbor, but they were far more likely to drink rum than tea when they returned to their homes. Conveniently, their actions actually deprived their wives, mothers, sisters and daughters, and not themselves. The colonists only resorted to an attempted boycott of rum in 1774, after Britain had closed the port of Boston. I guess it was time for drastic measures.

Similarly, when John Adams and other men in power thought it best to stop importing fine British fabrics with  which to make their clothing during the protests of the late 1760s, it had little impact on their daily lives. Wearing homespun cloth may not have been as comfortable nor look as refined as their regular clothing, but it was Abigail and other colonial wives and homemakers, not John and his fellow men, who were forced to spend hours spinning clothes to create their families’ wardrobes. Thus, in 1776, when Abigail begged John to remember the ladies while drafting the U.S. Constitution, she was not begging a favor, but demanding payment of an enduring debt. And her husband, in good conscience could not deny her right, or her important request.

which to make their clothing during the protests of the late 1760s, it had little impact on their daily lives. Wearing homespun cloth may not have been as comfortable nor look as refined as their regular clothing, but it was Abigail and other colonial wives and homemakers, not John and his fellow men, who were forced to spend hours spinning clothes to create their families’ wardrobes. Thus, in 1776, when Abigail begged John to remember the ladies while drafting the U.S. Constitution, she was not begging a favor, but demanding payment of an enduring debt. And her husband, in good conscience could not deny her right, or her important request.

Have you ever seen a picture of a Supreme Court session? Probably not. Photography is banned in Supreme Court, and there are only two known photographs of the Supreme Court in session. Cameras have long been banned inside the courtroom, so the only two photos were captured many decades ago by people who snuck cameras in.

Have you ever seen a picture of a Supreme Court session? Probably not. Photography is banned in Supreme Court, and there are only two known photographs of the Supreme Court in session. Cameras have long been banned inside the courtroom, so the only two photos were captured many decades ago by people who snuck cameras in.

The first photo, shown above, was shot in 1932 by a German photographer named Erich Salomon. Salomon was hired by Fortune magazine to shoot images during a tour of America. The photographer decided to sneak a camera into the Supreme Court by faking that he had a broken arm so that he could hide his camera inside his sling. Salomon was able to snap a stealthy photo, which was later published in Fortune and touted as the first photo ever made showing the court in session. That as a pretty sneaky way to get a camera into the courtroom, and while I don’t know how security is at the Supreme Court these days, but it wouldn’t surprise me to see a guard looking inside a sling to see what someone was trying to bring inside.

I can understand how a camera could be a problem, especially with old cameras. Many of them required a flash for indoor pictures, and having flashes going off all the time would be very distracting. Also, with today’s phones and cameras, videos could be taken easily, with sound that could let people outside the courtroom know about what was going inside the courtroom.

Nevertheless, five years later, in 1937, a young woman managed to take a second photo of the Supreme Court in session. This second photo was published in the June 7, 1937, edition of Time magazine, within an article titled Judiciary: Farewell Appearance. Time magazine wrote at the time, that the photo was taken by “an enterprising amateur, a young woman who concealed her small camera in her handbag, cutting a hole through which the lens peeped, resembling an ornament. She practiced shooting from the hip, without using the camera’s finder which was inside the purse.” The photographer was never named and remains a mystery to this day. The photo was also the first and only time all 9 justices of the court appeared in the same photo in session. There are rumors of a third photo of the Supreme court in session that was taken and published around the same time, but there does not appear to be any surviving record of that image.

Then, 77 years later, the inevitable happened. In 2014, an advocacy group snuck a camera into the Supreme Court and filmed the first-ever footage of the US Supreme Court in session. They captured a video that’s about 2-minutes long: The Supreme Court has officially banned cameras since 1946 when Federal Rule 53 was  enacted. It reads: Except as otherwise provided by a statute or these rules, the court must not permit the taking of photographs in the courtroom during judicial proceedings or the broadcasting of judicial proceedings from the courtroom. While Supreme Court justices have long been opposed to cameras in the courtroom, believing that cameras adversely impact the dynamic of the proceedings, they have been softening their stance in recent years. A number of justices have warmed up to the idea of cameras in the courtroom, possibly paving the way for a rule change in the future. I don’t know if I think that is a good thing or not, but somehow it seems that when you tell people they can’t do something, they ultimately find a way.

enacted. It reads: Except as otherwise provided by a statute or these rules, the court must not permit the taking of photographs in the courtroom during judicial proceedings or the broadcasting of judicial proceedings from the courtroom. While Supreme Court justices have long been opposed to cameras in the courtroom, believing that cameras adversely impact the dynamic of the proceedings, they have been softening their stance in recent years. A number of justices have warmed up to the idea of cameras in the courtroom, possibly paving the way for a rule change in the future. I don’t know if I think that is a good thing or not, but somehow it seems that when you tell people they can’t do something, they ultimately find a way.

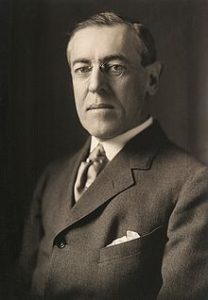

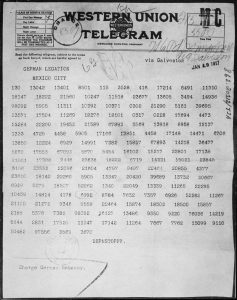

The United States has tried to stay out of most of the wars the rest of the world has become involved in, but sometimes circumstances have drawn us into wars we didn’t want to enter. World War I is a prime example of just such a situation. On February 26, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson learns of the so-called Zimmermann Telegram. The telegram was a message from German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador to Mexico proposing a Mexican-German alliance in the event of a war between the United States and Germany. This telegram was a crucial step toward the entry of the United States into World War I.

The United States has tried to stay out of most of the wars the rest of the world has become involved in, but sometimes circumstances have drawn us into wars we didn’t want to enter. World War I is a prime example of just such a situation. On February 26, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson learns of the so-called Zimmermann Telegram. The telegram was a message from German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador to Mexico proposing a Mexican-German alliance in the event of a war between the United States and Germany. This telegram was a crucial step toward the entry of the United States into World War I.

On February 24, 1917, British authorities gave Walter Hines Page, the United States ambassador to Britain, a copy of the Zimmermann Telegram. It was a coded message from Zimmermann to Count Johann von Bernstorff, the German ambassador to Mexico.  In the telegram, which was intercepted and deciphered by British intelligence in late January, Zimmermann instructed his ambassador, that in the event of a German war with the United States, to offer significant financial aid to Mexico, provided Mexico agreed to enter the conflict as a German ally. Germany also promised to restore to Mexico the lost territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Now, when you think about it, that is some big promises for Germany to be making, but I supposed that if the event of a loss in the war, all promises were null and void.

In the telegram, which was intercepted and deciphered by British intelligence in late January, Zimmermann instructed his ambassador, that in the event of a German war with the United States, to offer significant financial aid to Mexico, provided Mexico agreed to enter the conflict as a German ally. Germany also promised to restore to Mexico the lost territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Now, when you think about it, that is some big promises for Germany to be making, but I supposed that if the event of a loss in the war, all promises were null and void.

Upon learning about the proposed agreement between Germany and Mexico, the State Department was quick to send a copy of the Zimmermann Telegram to  President Wilson. The president was shocked by the note’s content and the next day proposed to Congress that the United States should start arming its ships against possible German attacks. Wilson also authorized the State Department to publish the telegram. It appeared on the front pages of American newspapers on March 1, and it left many Americans horrified. The telegram was quickly declared a forgery by the public, but two days later, Zimmermann himself announced that it was genuine.

President Wilson. The president was shocked by the note’s content and the next day proposed to Congress that the United States should start arming its ships against possible German attacks. Wilson also authorized the State Department to publish the telegram. It appeared on the front pages of American newspapers on March 1, and it left many Americans horrified. The telegram was quickly declared a forgery by the public, but two days later, Zimmermann himself announced that it was genuine.

The Zimmermann Telegram helped turn the American public, already angered by repeated German attacks on United States ships, firmly against Germany. On April 2, President Wilson, who had initially sought a peaceful resolution to World War I, urged immediate United States entrance into the war. Four days later, Congress declared war against Germany, and the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917.