Politics

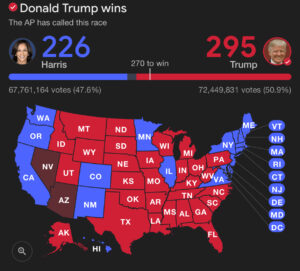

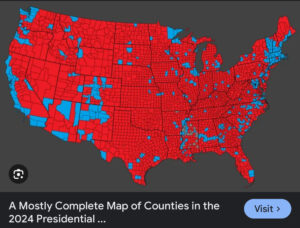

Yesterday, Americans went to the polls to elect our next president. We do this every four years, and whether your candidate wins or loses, it is a right that belongs to every US citizen over the age of 18 years. It isn’t a right that should be taken lightly. There are nations who do not have this right…and unfortunately, there are people who don’t vote and therefore forfeit their right. I understand that many people thing that their vote doesn’t matter, but every vote matters…every vote counts. I don’t care if you live in a state that is so completely red or so completely blue that you don’t think that your vote could possibly make a difference, it can. Change often happens slowly, but when enough people see a need for change, and they vote, change eventually happens. Take for example the states that flipped from Democrat to Republican in this election. People wanted change, and they went out to vote so they could get it.

Yesterday, Americans went to the polls to elect our next president. We do this every four years, and whether your candidate wins or loses, it is a right that belongs to every US citizen over the age of 18 years. It isn’t a right that should be taken lightly. There are nations who do not have this right…and unfortunately, there are people who don’t vote and therefore forfeit their right. I understand that many people thing that their vote doesn’t matter, but every vote matters…every vote counts. I don’t care if you live in a state that is so completely red or so completely blue that you don’t think that your vote could possibly make a difference, it can. Change often happens slowly, but when enough people see a need for change, and they vote, change eventually happens. Take for example the states that flipped from Democrat to Republican in this election. People wanted change, and they went out to vote so they could get it.

Of course, sometimes things have to get so bad that if makes people go out to vote. That can be the hardest part, because things do have to get pretty bad. Nevertheless, the people living in this era were born “for such a time as this.” We may not know it, but it is the truth. Each of us has face the times we are in, and we have decided whether we like what is going on or not. Then we act…but only if we get out and vote. Being angry, frustrated, or just done with it, will not create change. Only voting can do that…well, voting and much prayer. I’m sure you can tell which side of the coin I fall on, and that’s ok. I may be for one side or the other, but I firmly believe that people from both sides have a say, and a right to choose.

Of course, along with the right to vote, comes the right not to vote, and that too, is your right, but in my opinion, that is not the best way to go. My candidate may or may not win, as president, or any other office, but by voting, I have had my say in the matter. Sometimes, a win that is completely unexpected happens, because the voters turn out. You have tremendous power. That vote carries weight. It says, “I am making a stand!! This is how I see things…like it or not!! It’s my vote…and mine alone!! No one can make me vote one way or the other…or at all, but if I don’t vote, my voice is silenced.”

On October 24, 1945, the United Nations Charter, adopted and signed on June 26, 1945, came into effect. The United Nations (UN) emerged from a “perceived” need for a mechanism superior to the League of Nations in arbitrating international conflicts and negotiating peace. The escalating Second World War prompted the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union to draft the initial UN Declaration, which 26 nations signed in January 1942 as an official stance against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan. It all seemed like a good idea, and perhaps was drafted with good intentions, but it is my opinion that the UN has failed miserably to accomplish any of the goals it set out to achieve.

On October 24, 1945, the United Nations Charter, adopted and signed on June 26, 1945, came into effect. The United Nations (UN) emerged from a “perceived” need for a mechanism superior to the League of Nations in arbitrating international conflicts and negotiating peace. The escalating Second World War prompted the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union to draft the initial UN Declaration, which 26 nations signed in January 1942 as an official stance against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan. It all seemed like a good idea, and perhaps was drafted with good intentions, but it is my opinion that the UN has failed miserably to accomplish any of the goals it set out to achieve.

The foundational principles of the UN Charter were initially shaped during the San Francisco Conference, which began on April 25, 1945. This conference established the framework for a new international organization intended to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom.” The Charter further outlined two additional vital goals. They were to maintain the principles of equal rights and self-determination for all peoples…initially intended to safeguard smaller nations at risk of being overtaken by the larger Communist powers emerging after the war, and to promote international collaboration to tackle worldwide economic, social, cultural, and humanitarian issues.

Following the war’s end, the responsibility of negotiating and maintaining peace was assigned to the newly established UN Security Council, which included the United States, Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and China. Each member possessed veto power. Winston Churchill implored the United Nations to employ its charter to promote a new, united Europe…a unity characterized by its opposition to communist expansion in both the East and the West. Yet, given the composition of the Security Council, achieving this proved more challenging than anticipated. I suppose that the distain felt by many people, for the United Nations, could have arisen from an impossible task, but more likely it came from flawed people who placed their own agenda ahead of the real needs of the people.

The United Nations is subject to criticism for a variety of reasons, including its policies, ideology, equality of representation, administrative practices, enforcement of decisions, and perceived ideological biases. Critics often cite a lack of success within the organization, noting failures in both preventative measures and in de-escalating conflicts ranging from social disputes to full-blown wars. Additional criticisms involve accusations of antisemitism, appeasement, collusion, promotion of globalism, inaction, and the exertion of undue influence by

powerful nations within the General Assembly, as well as corruption and misallocation of resources. In my opinion, and that of many other people, that the UN should be dissolved, or at the very least, that the United States should withdraw and expel the United Nations from this nation. While some may disagree, this is my viewpoint.

powerful nations within the General Assembly, as well as corruption and misallocation of resources. In my opinion, and that of many other people, that the UN should be dissolved, or at the very least, that the United States should withdraw and expel the United Nations from this nation. While some may disagree, this is my viewpoint.

Each American presidency is marked by a defining moment, an event that encapsulates its tenure. For John F. Kennedy’s presidency, the Cuban Missile Crisis stood as that pivotal event. The most intense phase of the crisis, often referred to as the “13 Days,” spanned from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy was informed of the Soviet missile sites being built in Cuba, to October 28, 1962, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev declared the dismantling of the missiles. On October 22, 1962, when it came time to tell the American people about the situation, President Kennedy revealed in a televised address of profound significance, that American spy planes had detected Soviet missile bases in Cuba. This represented a very dangerous situation for the United States. The missile sites were still under construction, but they were close to completion, and they contained medium-range missiles with the capacity to hit several major US cities, including Washington DC.

Each American presidency is marked by a defining moment, an event that encapsulates its tenure. For John F. Kennedy’s presidency, the Cuban Missile Crisis stood as that pivotal event. The most intense phase of the crisis, often referred to as the “13 Days,” spanned from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy was informed of the Soviet missile sites being built in Cuba, to October 28, 1962, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev declared the dismantling of the missiles. On October 22, 1962, when it came time to tell the American people about the situation, President Kennedy revealed in a televised address of profound significance, that American spy planes had detected Soviet missile bases in Cuba. This represented a very dangerous situation for the United States. The missile sites were still under construction, but they were close to completion, and they contained medium-range missiles with the capacity to hit several major US cities, including Washington DC.

Kennedy declared he was imposing a naval “quarantine” on Cuba to block Soviet ships from delivering additional offensive weapons to the island. He stated that the United States would not accept the current missile sites’ presence. The president emphasized that America was prepared to take military action to eliminate what he described as a “secretive, irresponsible, and provocative threat to global peace.”

The Cuban Missile Crisis, as it became known, began on October 14, 1962, when US intelligence, analyzing data from a U-2 spy plane, discovered that the Soviet Union was constructing medium-range missile sites in Cuba. The following day, President Kennedy convened a secret emergency meeting with his top military, political, and diplomatic advisers to address the grave situation. This group came to be known as ExComm, an abbreviation for Executive Committee. Opting against a surgical air strike on the missile sites, ExComm instead chose a naval blockade and demanded the dismantling and removal of the missiles. It was then, on the evening of October 22, that President Kennedy disclosed his decision on national television. Tensions continued to mount over the ensuing six days, to a critical point, and placing the world on the edge of nuclear warfare between the two superpowers.

On October 23, the United States initiated a naval “quarantine” of Cuba. However, President Kennedy opted to allow Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev additional time to contemplate the US maneuver by moving the quarantine line back 500 miles. By October 24, Soviet vessels bound for Cuba, capable of transporting military cargo, seemed to have decelerated, changed course, or turned around as they neared the quarantine zone, except for one ship…the tanker Bucharest. Following appeals from over 40 nonaligned countries, UN Secretary-General U Thant made private overtures to Kennedy and Khrushchev, imploring their administrations to “avoid any actions that might worsen the situation and pose a risk of war.” Under orders from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, United States armed forces escalated to DEFCON 2, the most critical military readiness level ever achieved in the postwar period, while commanders readied for an all-out conflict with the Soviet Union.

On October 25, the aircraft carrier USS Essex and the destroyer USS Gearing tried to intercept the Soviet tanker Bucharest as it breached the US quarantine of Cuba. The Soviet vessel did not comply, but the US Navy refrained from taking it by force, judging that it was unlikely to be carrying offensive weapons. On October 26, Kennedy was informed that construction on the missile bases continued unabated, and ExComm contemplated a US invasion of Cuba. The Soviets apparently felt the tension of their actions, because on that same day, they offered a deal to resolve the crisis: they would dismantle the missile bases in return for a United States guarantee not to invade Cuba.

The following day, Khrushchev escalated the situation by publicly demanding the removal of US missile bases in Turkey, influenced by Soviet military leaders. As Kennedy and his advisors deliberated over this perilous shift in negotiations, a U-2 spy plane was downed over Cuba, resulting in the death of its pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson. It looked like thing might have reached the boiling point, but despite the Pentagon’s dismay, Kennedy prohibited any military response unless further surveillance aircraft were targeted over Cuba. To alleviate the intensifying crisis, Kennedy and his team decided to dismantle the US missile installations in Turkey at a subsequent time, to avoid provoking Turkey, who was an essential NATO ally.

On October 28, Khrushchev declared his government’s decision to dismantle and remove all offensive Soviet weapons from Cuba. Following the broadcast of this public announcement on Radio Moscow, the USSR affirmed its readiness to adopt the resolution secretly suggested by the Americans the previous day. That afternoon, Soviet technicians started dismantling the missile sites, averting the imminent threat of nuclear war. The Cuban Missile Crisis had effectively ended. In November, Kennedy lifted the blockade, and by year’s end, all offensive missiles were removed from Cuba. Later, the United States discreetly withdrew its missiles from Turkey.

At the time, the Cuban Missile Crisis appeared to be a definitive triumph for the United States. In this, Cuba gained a heightened sense of security following the crisis. The withdrawal of obsolete Jupiter missiles from Turkey did not negatively impact the United States’ nuclear strategy. Nevertheless, the crisis spurred the USSR, feeling humiliated, to initiate a substantial nuclear arms expansion. By the 1970s, the Soviet Union had achieved nuclear parity with the United States and developed intercontinental ballistic missiles with the capability to target any city within the United States.

The presidents that followed Kennedy upheld his promise to refrain from invading Cuba, and the relationship with the communist nation, located a mere 80 miles off the coast of Florida, continued to challenge United States foreign policy for over half a century. Finally, in 2015, representatives from both countries declared the official normalization of United States-Cuba relations, encompassing the relaxation of travel bans and the establishment of embassies and diplomatic offices in each nation.

For Kennedy, this pivotal moment in his administration showcased his ability to manage a high-stakes international crisis. His decision to implement a naval blockade and negotiate with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev helped avoid a potential nuclear war. It also demonstrated his leadership and diplomatic skills, as he balanced military readiness with diplomatic negotiations, which ultimately led to the removal of Soviet missiles from Cuba. The successful resolution of the crisis significantly boosted Kennedy’s public image, portraying him as a strong and capable leader who could protect the United States from external threats. The crisis was a defining moment in the Cold War, highlighting the intense rivalry between the United States and the

Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it also led to the establishment of a direct communication line between Washington and Moscow, known as the “hotline,” to prevent future crises. In summary, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a defining event that not only tested Kennedy’s presidency, but it also shaped his legacy as a leader who could navigate the complexities of international relations during one of the most dangerous periods of the Cold War.

Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it also led to the establishment of a direct communication line between Washington and Moscow, known as the “hotline,” to prevent future crises. In summary, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a defining event that not only tested Kennedy’s presidency, but it also shaped his legacy as a leader who could navigate the complexities of international relations during one of the most dangerous periods of the Cold War.

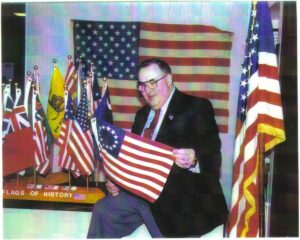

We have all heard about the importance of thinking ahead. It’s important in many situations, but unfortunately, it isn’t always appreciated. One case of forward thinking that rather backfired is the case of Robert G Heft. Heft, who went by Bob, was in high school in 1958, when his history teacher, Stanley Pratt, asked his class to make anything they wanted and bring it in for a show-and-tell. Heft took a little bit different approach than his classmates, and it rather backfired. While most of his classmates designed a conventional approach for their class project, Heft decided to do something a little more ambitious.

We have all heard about the importance of thinking ahead. It’s important in many situations, but unfortunately, it isn’t always appreciated. One case of forward thinking that rather backfired is the case of Robert G Heft. Heft, who went by Bob, was in high school in 1958, when his history teacher, Stanley Pratt, asked his class to make anything they wanted and bring it in for a show-and-tell. Heft took a little bit different approach than his classmates, and it rather backfired. While most of his classmates designed a conventional approach for their class project, Heft decided to do something a little more ambitious.

It was a noble effort, and definitely forward thinking, but when Heft brought his flag to school, his teacher was not impressed. Years later, Heft recalled, “He told me, ‘Why you got too many stars? You don’t even know how  many states we have.'” Heft received a B- for his project. Nevertheless, he was offered an opportunity to enhance his grade by persuading the US government to adopt his flag design. Despite the slim chances, Heft was determined. He initiated a campaign, writing letters and placing calls to the White House, urging the president to consider his flag.

many states we have.'” Heft received a B- for his project. Nevertheless, he was offered an opportunity to enhance his grade by persuading the US government to adopt his flag design. Despite the slim chances, Heft was determined. He initiated a campaign, writing letters and placing calls to the White House, urging the president to consider his flag.

Two years after Alaska and Hawaii were admitted as states, Heft was surprised with a call from President Dwight D Eisenhower, informing him that his design had been selected for the new 50-star flag. On July 4, 1960, Heft was honored with an invitation from President Eisenhower to attend a flag-raising ceremony at the US Capitol in Washington DC. Even Heft’s history teacher was impressed, saying, “I guess if it’s good enough for Washington, it’s good enough for me. I hereby change the grade to an A.” Well, that took a fair amount of decency on the part of the teacher. He could have let it go, but he didn’t.

Since that time, Heft’s banner has established a new record as the longest-serving U.S. flag. Heft pursued a career as a professor at Northwest State Community College in Archbold, Ohio, and held the position of mayor in Napoleon, Ohio. He gained recognition as a motivational speaker and made 14 visits to the White House. Anticipating future changes, Heft also crafted a 51-star American flag in the event that Washington DC, or Puerto Rico achieves statehood. His 51-star flag design features six alternating rows of stars with nine and

eight stars each.

eight stars each.

Heft, born in Saginaw, Michigan on January 19, 1942. He left Michigan following his parents’ separation when he was around a year old. He returned upon retiring from his professorship at Northwest State Community College in Archbold, Ohio. Robert G Heft, who passed away on December 12, 2009, at a hospital in Saginaw, Michigan, at the age of 67, will always be remembered as the student who created the 50-star American flag design.

The USS Cole, an American naval destroyer, captained by Commander Kirk Lippold, arrived in Aden, Yemen at the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula for refueling, en route to join US warships enforcing trade sanctions against Iraq. At 12:15pm local time, a motorized rubber dinghy filled with explosives created a 40-by-40-foot hole in the port side of the ship, while it was docked for refueling in Aden. How could it have been that easy? The attack, which resulted in the death of seventeen sailors and wounded thirty-eight, was perpetrated by two suicide terrorists believed to be affiliated with Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda network.

The USS Cole, an American naval destroyer, captained by Commander Kirk Lippold, arrived in Aden, Yemen at the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula for refueling, en route to join US warships enforcing trade sanctions against Iraq. At 12:15pm local time, a motorized rubber dinghy filled with explosives created a 40-by-40-foot hole in the port side of the ship, while it was docked for refueling in Aden. How could it have been that easy? The attack, which resulted in the death of seventeen sailors and wounded thirty-eight, was perpetrated by two suicide terrorists believed to be affiliated with Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda network.

The blast resulted in significant flooding aboard the warship, causing it to list slightly. Nevertheless, by nightfall, the crew had successfully halted the water flooding in, thereby keeping the Cole afloat. Following the assault, President Bill Clinton directed US vessels in the Persian Gulf to evacuate the area and proceed to the open sea. He then dispatched large contingent of American investigators to Aden for a thorough inquiry. The group included FBI agents dedicated to probing potential connections to Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden had already been indicted in the United States for orchestrating the 1998 embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, which claimed the lives of 224 individuals, among them 12 Americans, so it was not a far stretch to think he would have a hand in this attack too.

The USS Cole’s brief four-hour stopover indicates that the terrorists had inside information about its unscheduled visit to the Aden fueling station. The small boat used by the terrorists merged seamlessly with other harbor vessels aiding the Cole’s mooring process and managed to get close to the US warship undetected. Upon detonation of their dinghy, a substantial explosion ripped through the Cole’s port side, causing extensive damage to the engine room, mess hall, and living quarters. Witnesses aboard the Cole reported seeing both terrorists stand up moments before the blast, typical of suicide bombers.

In all, six individuals were suspected of involvement in the Cole attack. They were quickly detained in Yemen, but due to the lack of cooperation from Yemeni officials, the FBI has been unable to definitively connect the

attack to bin Laden, even though we all know that he masterminded it. This kind of attack was so typical of the type of attack that would later make bin Laden well known as a major player in attacks against American targets. As for Americans, these leaks and the inability of the FBI to resolve the issue are some of the biggest reasons that many Americans don’t trust the FBI today.

attack to bin Laden, even though we all know that he masterminded it. This kind of attack was so typical of the type of attack that would later make bin Laden well known as a major player in attacks against American targets. As for Americans, these leaks and the inability of the FBI to resolve the issue are some of the biggest reasons that many Americans don’t trust the FBI today.

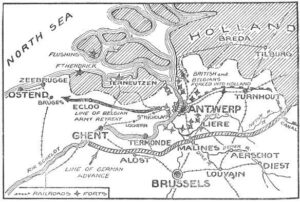

The initiative to send a relief army to support Antwerp did not begin with Winston Churchill, but with Lord Kitchener and the French Government. Churchill was not involved or consulted about the plans until they were well underway, with significant troop movements already in progress or planned. Deciding that he should be brought into the loop, Churchill was summoned to a midnight meeting at Lord Kitchener’s residence on October 2, 1914. It was during this meeting that he fully grasped the progress of the plans to send a relief army to Antwerp, a coordination between Lord Kitchener and the French Government. He learned as well that no definitive commitments had been made to the Belgian Government. On that same afternoon, the Belgian Government had resolved to evacuate Antwerp, pull back the field army from the fort, and effectively abandon the city’s defense.

The initiative to send a relief army to support Antwerp did not begin with Winston Churchill, but with Lord Kitchener and the French Government. Churchill was not involved or consulted about the plans until they were well underway, with significant troop movements already in progress or planned. Deciding that he should be brought into the loop, Churchill was summoned to a midnight meeting at Lord Kitchener’s residence on October 2, 1914. It was during this meeting that he fully grasped the progress of the plans to send a relief army to Antwerp, a coordination between Lord Kitchener and the French Government. He learned as well that no definitive commitments had been made to the Belgian Government. On that same afternoon, the Belgian Government had resolved to evacuate Antwerp, pull back the field army from the fort, and effectively abandon the city’s defense.

The men were deeply troubled by the Belgian Government’s plan. It appeared that just as help was within reach, everything might be sacrificed for a mere three or four days of further resistance. Under these conditions, Churchill proposed to immediately travel to Antwerp to inform the Belgian Government of the ongoing efforts, assess the situation firsthand, and explore how the defense could be extended until a relief force was ready. The others agreed to Churchill’s proposal, and he promptly made his way across the Channel.

The next day, after discussions with the Belgian Government and British Staff officers in Antwerp overseeing the operations, Churchill presented a cautious telegraphic proposal. He avoided any declarations on behalf of the British Government that might encourage the Belgians to hold out for support he couldn’t guaranteed.

Churchill’s proposal was concise and transmitted via telegram. It stated: “The Belgians were to continue the resistance to the utmost limit of their power. The British and French Governments were to say within three days definitely whether they could send a relieving force or not, and what the dimensions of that force would be.

In the event of their not being able to send a relieving force the British Government were to send in any case to Ghent and other points on the line of retreat British troops sufficient to insure the safe retirement of the Belgian field army, so that the Belgian  field army would not be compromised through continuing the resistance on the Antwerp fortress line.

field army would not be compromised through continuing the resistance on the Antwerp fortress line.

Incidentally, we were to aid and encourage the defense of Antwerp by the sending of naval guns, naval brigades, and any other minor measures likely to enable the defenders to hold out the necessary number of days.”

The proposal was contingent upon approval from both parties. It remained unsettled until it received the acceptance of both governments. Upon agreement, Churchill received a telegraph announcing the dispatch of a relief army, including its size and structure, which I was to communicate to the Belgians. Churchill was instructed to do all in his power to sustain the defense in the interim, which he did, disregarding any potential repercussions.

Churchill chose not to recount the well-known military events, but he believed it would be erroneous to view Lord Kitchener’s attempts to relieve Antwerp, in which Churchill had a significant but secondary role, as a venture that resulted solely in adversity.

Churchill believed that military history would deem the outcomes highly favorable to the Western Allies. The significant battle that began on the Aisne was extending daily towards the sea. Sir John French’s forces were assembling and commencing the Battle of Armentières, which led to the pivotal Battle of Ypres, amid an ever-changing situation.

The prolonged defense of Antwerp, even by just a few days, detained substantial German forces near the fortress. The sudden and audacious deployment of a new British division and a British cavalry division at Ghent, among other places, perplexed the cautious German command, causing them to anticipate the arrival of a large force from the sea.

Regardless, their advance was tentative, faced with only weak opposition, and Churchill was convinced that history would confirm, certainly in his view and that of many esteemed military officers of the time, that the

entirety of this operation…the movement of the British and associated French troops…though it failed to save Antwerp, resulted in the great battle being fought along the Yser, rather than twenty or thirty miles to the south, and if that was the case, then the losses sustained by the naval division, fortunately not severe in terms of lives, will undoubtedly have been justified for the greater good.

entirety of this operation…the movement of the British and associated French troops…though it failed to save Antwerp, resulted in the great battle being fought along the Yser, rather than twenty or thirty miles to the south, and if that was the case, then the losses sustained by the naval division, fortunately not severe in terms of lives, will undoubtedly have been justified for the greater good.

In the late 1960s, Chicago was engulfed in turmoil. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, sparked riots throughout the United States, leaving Chicago’s West Side in ruins. Mayor Richard J Daley infamously ordered a “shoot to kill” directive for arsonists. It was a vast difference from the way riots were handled in the 2020 era, after the killing of George Floyd, when riots were not only allowed, but encouraged. Nevertheless, in Chicago in 1968, chaos reigned then and again during the Democratic National Convention a few months later, culminating in a confrontation between protesters and police that a national commission later described as a “police riot.”

In the late 1960s, Chicago was engulfed in turmoil. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, sparked riots throughout the United States, leaving Chicago’s West Side in ruins. Mayor Richard J Daley infamously ordered a “shoot to kill” directive for arsonists. It was a vast difference from the way riots were handled in the 2020 era, after the killing of George Floyd, when riots were not only allowed, but encouraged. Nevertheless, in Chicago in 1968, chaos reigned then and again during the Democratic National Convention a few months later, culminating in a confrontation between protesters and police that a national commission later described as a “police riot.”

The year 1969 seemed to mark a period of calm until the commencement of a conspiracy trial targeting the Democratic convention protest organizers, which ignited a new phase in the clash between the counterculture and the “establishment.” This battle shifted from the streets to the realm of public opinion. While the defendants attempted to mock and censure the government, represented by Judge Julius Hoffman in the courtroom, a separate faction of youth chose to take a more extreme stance in protesting the government and the ongoing Vietnam conflict. Their strategy was to “bring the war home” through four “Days of Rage.” It amazes me that these people think that destroying their own “home turf” and the businesses that are there, would somehow generate support for their cause…and then they want the American people to pay for the repairs!!

“Every day that the war [in Vietnam] went on, two thousand innocent people would be killed. So, there was a kind of urgency that took over. And in that context, we faced each other and tried to figure out, what do you do to end a war? How do you stop it,” Bill Ayers, an organizer of the Days of Rage, told WTTW decades later. Ayers and his fellow protesters belonged to the activist group Students for a Democratic Society but were starting to diverge from the main SDS body. They named themselves the Weathermen, inspired by a lyric in a Bob Dylan song, “Subterranean Homesick Blues” which stated, “You don’t need a weather man to know which way the wind blows.”

The Weathermen believed that the peaceful methods of other SDS factions were ineffective, so they organized for thousands to converge on Chicago, coinciding with the commencement of the Chicago Eight conspiracy trial two weeks later. “A huge outpouring of militance, of young people. We felt that we ought to call a demonstration in which we weren’t contained and controlled,” Ayers said. However, as the Days of Rage commenced, the Weathermen discovered their support was significantly less than anticipated. On October 8, 1969, they assembled in Lincoln Park to initiate their violent protests—donning football helmets and shoulder pads, and arming themselves with steel pipes, chains, slingshots, and baseball bats—yet only a few hundred individuals participated, a stark contrast to the fifty thousand they had expected.

On that initial evening in 1969, protesters headed south toward the Drake Hotel, the residence of Judge Hoffman, shattering the windows of vehicles and shops in their path. Following their assault on police barricades, law enforcement quelled the disturbances with countermeasures, deploying tear gas, nightsticks, and firearms. Although some Weathermen were shot and officers sustained injuries, there were no fatalities. “The thought of the Chicago Police Department and the mayor of the city of Chicago was to try to avoid confrontation,” Richard Elrod, a state legislator and attorney for the city who had been tasked with handling the riots, told WTTW decades later. Ayers disagreed, saying, “I don’t think the police, or the city learned a thing between ’68 and ’69.” The police faced widespread criticism for their management of the protests at the Democratic convention the previous year.

Other activists criticized the tactics of the Weathermen. “We thought it was off the wall,” Carl Davidson, a leader of SDS, told WTTW. “We thought it was silly, counterproductive, that it wasn’t going anywhere. That’s the best we thought of it.” A different branch of SDS coordinated peaceful protests with the Black Panthers against the Vietnam War and persistent racial inequality, attracting thousands of participants. However, it was the minor yet violent actions of the Weathermen that captured media attention. Even Ayers later expressed doubt about the riots, saying “I don’t think that the Days of Rage was a particularly smart or effective tactic. I think it was a very difficult time to know what to do, but we were determined to see through our strategy of militant opposition and trying to mobilize all of the militants to come to Chicago to display their anger, their outrage, and their deep opposition to this war. That was a colossal failure, in the sense that we didn’t mobilize lots of people to come.”

The subsequent Days of Rage were less intense, yet on October 11, the Weathermen gathered at a statue of a policeman they had previously bombed in the lead-up to the Days of Rage and proceeded into the Loop. They once again engaged with the police, an event described in a 1994 retrospective article by the Chicago Tribune as a “vicious melee that resulted in nearly 300 arrests, 48 police injuries and unknown more to protesters.” In the midst of the confrontation, Richard Elrod sustained a neck injury that resulted in paralysis from the neck down, although he later regained some movement but continued to suffer partial paralysis. Elrod reported that he had attempted to tackle Brian Flanagan, a 22-year-old protester, who retaliated by kicking him in the neck with steel-toed boots. Flanagan, who was ultimately acquitted on all counts, contended that Elrod collided with a concrete wall during his attempted tackle. The subsequent year, Elrod was elected as the Cook County sheriff and subsequently ascended to the position of a Circuit Court judge.

Former state legislator and Cook County sheriff Richard Elrod, who is shown in a photo from the early 2000s, suffered a broken neck during the Days of Rage. That confrontation marked the end of the Days of Rage. The Weathermen, in certain respects, “brought the war home.” However, their protests might have inadvertently enhanced the police’s reputation and undermined the causes they supported by linking anti-war and anti-racism demonstrations with violence in public perception. Following the Days of Rage, a lengthy magazine feature overtly supportive of the police and the city appeared in the Chicago Tribune, which asserted that “the police, widely condemned scarcely a year ago for their conduct during the Democratic convention, had never enjoyed so much public acclaim.”

Months later, the Weathermen were forced underground when a bomb they were constructing inadvertently detonated, killing three of their leaders in New York City. In the following decades, participants of the Days of Rage began to turn themselves in to the authorities. One of the last to do so was Jeffrey David Powell, who surrendered in 1994 and was sentenced to a fine and 18 months of probation. Ayers, along with his wife Bernardine Dohrn, another member of the Weathermen, surrendered in 1981. While Dohrn was fined and placed on probation, charges against Ayers, whose father was a president at Commonwealth Edison, were dismissed due to illicit FBI methods used against him. He went on to become a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and gained brief national attention during the 2008 presidential election for his association with Barack Obama. Dohrn secured a position as a professor at the Children and Family Justice Center at Northwestern University’s Law School.

The Days of Rage had receded into the annals of history. However, as reported by the Chicago Tribune at the time of Powell’s surrender, “the Days of Rage symbolized a marked fissure in American society, the end of the carefree ‘60s, when rich, white college kids clashed with police, their parents, the government in protest against the Vietnam War, racial intolerance and just about everything else that had served as the status quo.”

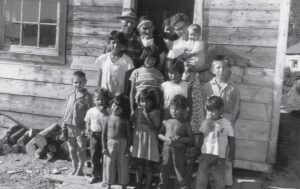

The Sixties Scoop, often referred to simply as The Scoop, was a time when policies in Canada allowed child welfare authorities to remove Indigenous children from their families and communities to place them in foster homes. These children were then adopted by white families. Although it is called the Sixties Scoop, this practice started in the mid-to-late 1950s and continued until the 1980s. There was no given indication that these children were neglected or mistreated, just that they were Indigenous, and supposedly, therefore would be better off in the care of white families. During those years, an estimated 20,000 Indigenous children were removed from their families and placed predominantly with white middle-class families.

The Sixties Scoop, often referred to simply as The Scoop, was a time when policies in Canada allowed child welfare authorities to remove Indigenous children from their families and communities to place them in foster homes. These children were then adopted by white families. Although it is called the Sixties Scoop, this practice started in the mid-to-late 1950s and continued until the 1980s. There was no given indication that these children were neglected or mistreated, just that they were Indigenous, and supposedly, therefore would be better off in the care of white families. During those years, an estimated 20,000 Indigenous children were removed from their families and placed predominantly with white middle-class families.

The program’s policies were not uniform, with each province implementing distinct foster programs and adoption policies. Saskatchewan was unique in having the targeted Indigenous transracial adoption program known as the Adopt Indian Métis (AIM) Program. The term “Sixties Scoop” was first used in the early 1980s by social workers from the British Columbia Department of Social Welfare to describe the practice of child apprehension by their department. This term made its initial appearance in print in a 1983 report by the Canadian Council on Social Development, entitled “Native Children and the Child Welfare System.” Researcher Patrick Johnston cited the term’s origin and utilized it in his report. This term is akin to “Baby Scoop Era,” denoting the time from the late 1950s to the 1980s when many children were removed from unmarried mothers for adoption. These mothers were given no choice in the matter.

The government policies responsible for the Sixties Scoop were abandoned in the mid-1980s following resolutions passed by Ontario chiefs and severe condemnation from a Manitoba judicial inquiry. The inquiry, led by Associate Chief Judge Edwin C. Kimelman, culminated in the release of “No Quiet Place / Review Committee on Indian and Métis Adoptions and Placements,” commonly referred to as the “Kimelman Report.” Numerous lawsuits have been initiated in Canada by individuals who were part of the Sixties Scoop, including class-action suits in five provinces, such as the one initiated in British Columbia in 2011. Chief Marcia Brown Martel of the Beaverhouse First Nation was the lead plaintiff in the Ontario class-action suit filed in 2009. On February 14, 2017, Justice Edward Belobaba of the Ontario Superior Court found the government responsible for damages caused by the Sixties Scoop. Subsequently, on October 6, 2017, an $800-million settlement was disclosed for the Martel case. Currently, Métis and non-status First Nations individuals are not included in the settlement, prompting the National Indigenous Survivors of Child Welfare Network…an organization led by survivors of the Sixties Scoop in Ottawa…to call for the rejection of the settlement unless it encompasses all Indigenous individuals who were removed from their homes and placed into forced adoption.

The Sixties Scoop began during a period when Indigenous families were already grappling with the consequences of the Canadian Indian residential school system. This network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples adversely affected their social, economic, and living conditions. The residential school system remained operational until the closure of the last school in 1996. Established by the federal government and managed by various churches, the system’s goal was to assimilate Aboriginal children by teaching them Euro-Canadian and Christian values. It enforced policies that prohibited the children from speaking their native languages, communicating with their families, or practicing their cultural traditions. Survivors of residential schools have spoken out about the physical, spiritual, sexual, and psychological abuse they endured from the staff. The enduring cultural impact on First Nations, Métis, and Inuit families and communities is both widespread and profound.

The Sixties Scoop involved the forced removal of children from their Indigenous lands and communities, often without the consent or knowledge of their families or tribes. Siblings were frequently separated and sent to different areas to prevent any communication with their relatives. These children were denied knowledge of their true nationality, history, or family ties. If a child sought to learn about their cultural identity, they required consent from their biological parents. However, due to the government’s efforts to sever ties between the children and their biological families, access to their birth records was impossible. Consequently, while the children might have suspected their cultural heritage, they had no means to verify it with concrete evidence.

The Canadian government began the process of closing the mandatory residential school system in the 1950s and 1960s, believing that Aboriginal children would receive a superior education within the public school system. A summary states: “This transition to provincial services led to a 1951 [Indian Act] amendment that enabled the province to provide services to Aboriginal people where none existed federally. Child protection was one of these areas. In 1951, twenty-nine Aboriginal children were in provincial care in British Columbia; by 1964, that number was 1,466. Aboriginal children, who had comprised only 1 percent of all children in care, came to make up just over 34 percent.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada, established as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, was tasked with recording the experiences of Indigenous children in residential schools. Its mission was to disseminate the truths of survivors, their families, communities, and all those impacted, to the Canadian populace. The TRC’s final report, released in 2015, details these findings: “By the end of the 1970s, the transfer of children from residential schools was nearly complete in Southern Canada, and the impact of the Sixties Scoop was in evidence across the country.” First Nations have persistently resisted such policies through various means, including legal challenges (Natural Parents v. Superintendent of Child Welfare, 1976, 60 D.L.R. 3rd 148 S.C.C) and the establishment of their own policies, like the Spallumcheen Indian Band’s by-law to manage its child welfare program, achieving varying levels of success.

In response to the loss of their children and the subsequent cultural genocide, First Nations communities took

action by repatriating children from failed adoptions and striving to reclaim authority over their children’s welfare practices. This movement began in 1973 with the Blackfoot (Siksika) child welfare agreement in Alberta. Currently, there are approximately 125 First Nations Child and Family Service Agencies in Canada, operating under a variety of agreements that grant them authority from provincial governments to offer services, with funding provided by the federal government.

action by repatriating children from failed adoptions and striving to reclaim authority over their children’s welfare practices. This movement began in 1973 with the Blackfoot (Siksika) child welfare agreement in Alberta. Currently, there are approximately 125 First Nations Child and Family Service Agencies in Canada, operating under a variety of agreements that grant them authority from provincial governments to offer services, with funding provided by the federal government.

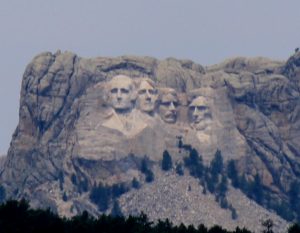

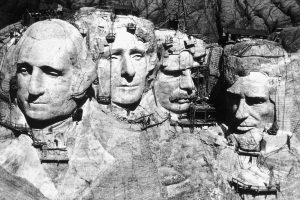

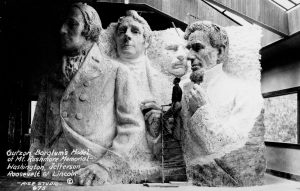

One of the most iconic monuments in the United States, in my opinion is that of Mount Rushmore. I’m sure some people might not agree with me on that, but I have been to Mount Rushmore more times than I could possibly count, and it just never gets old. The monument was the vision of Doane Robinson, a South Dakota historian who was looking to draw more visitors to the state. While that was a cool idea, it was dwarfed, in the end, by the absolute grandeur of the finished product. Maybe it was the vision of the sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, who Robinson commissioned to chisel the faces into the mountain, or maybe it was because it would transform a mountain into an awesome tribute to four really great presidents. I can’t say for sure, but the monument ended up being so much more than a tourist attraction. Every time I am there, I feel the awesomeness of the place, almost as if it is hallowed ground…though not in the Biblical sense.

One of the most iconic monuments in the United States, in my opinion is that of Mount Rushmore. I’m sure some people might not agree with me on that, but I have been to Mount Rushmore more times than I could possibly count, and it just never gets old. The monument was the vision of Doane Robinson, a South Dakota historian who was looking to draw more visitors to the state. While that was a cool idea, it was dwarfed, in the end, by the absolute grandeur of the finished product. Maybe it was the vision of the sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, who Robinson commissioned to chisel the faces into the mountain, or maybe it was because it would transform a mountain into an awesome tribute to four really great presidents. I can’t say for sure, but the monument ended up being so much more than a tourist attraction. Every time I am there, I feel the awesomeness of the place, almost as if it is hallowed ground…though not in the Biblical sense.

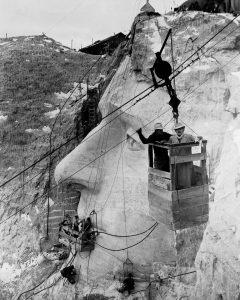

The sculpting of Mount Rushmore was a monumental task, particularly in 1927. Nevertheless, the carving began on October 4th on the likenesses of the four great men of Mount Rushmore, located in the Black Hills National Forest of South Dakota. The project was to be far from quickly finished. Instead, it would take an additional 12 years to complete the granite likenesses of four esteemed American presidents…George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. Each time a likeness was completed, it was big news, and people came from miles around to watch the unveiling ceremony. Of course, the project was not without conflict. The Lakota Sioux people, who consider the Black Hills to be sacred ground, strongly opposed the project. The mountain was previously part of the Great Sioux Reservation before being taken away  from them by the US government. Nevertheless, there were no skirmishes over the project, and these days, the likeness of Crazy Horse is also being carved into a mountain in the Black Hills.

from them by the US government. Nevertheless, there were no skirmishes over the project, and these days, the likeness of Crazy Horse is also being carved into a mountain in the Black Hills.

The first face “chiseled” by Borglum, was that of George Washington. Initially, Borglum sculpted the head in an egg shape and added the features afterward. The plan was to place Thomas Jefferson’s likeness to the right of Washington, but after two years, it developed severe cracks. The workers were forced to remove the damaged sculpture with dynamite. They tried going deeper, but the kept coming up with more quartz, which was unsuitable for the enduring sculpture that today exists on Mount Rushmore. So, Borglum repositioned Jefferson on Washington’s left side and started again.

Washington’s face was completed in 1934. Jefferson’s was dedicated in 1936…with then…president Franklin Roosevelt in attendance. Lincoln’s likeness was completed a year later. In 1939, Teddy Roosevelt’s face was completed. The project, which cost $1 million, was funded primarily by the federal government. When we think of sculpting in stone, we think of hammers and chisels, but much of Mount Rushmore was “sculpted” with dynamite. With 450,000 tons of granite to be removed, chisels were definitely not going to be enough. Throughout the fourteen years of carving, from 1927 to 1941, nearly 400 workers, including both men and women, labored at the memorial. The work was demanding, the hours extensive, the wages modest, and job security was unpredictable. Even under severe and perilous conditions, there were no fatalities during the carving process. While for some, this work represented merely a job, for others, it evolved into a profound vocation. For those that embraced the project, I can imagine that they somehow felt the same sense of this being hallowed ground that I feel each time I’m there.

At the time of Borglum’s death, the sculpture was not finished. He continued to touch up his work at Mount Rushmore until he died suddenly in 1941. Borglum had originally hoped to also carve a series of inscriptions into the mountain, outlining the history of the United States. After his passing, his son Lincoln Borglum finished

the sculpture to its current point. It isn’t exactly the sculpture Gutzon Borglum has imagined, because it was to have featured the presidents to their waists, but I think it is perfect as it stands today, from its four carved heads to the secret room, known as “The Hall of Records,” behind the structure, that no one is permitted to see without an act of Congress. That is something I would love to be allowed to see someday. As it stands, it too remains unfinished.

the sculpture to its current point. It isn’t exactly the sculpture Gutzon Borglum has imagined, because it was to have featured the presidents to their waists, but I think it is perfect as it stands today, from its four carved heads to the secret room, known as “The Hall of Records,” behind the structure, that no one is permitted to see without an act of Congress. That is something I would love to be allowed to see someday. As it stands, it too remains unfinished.

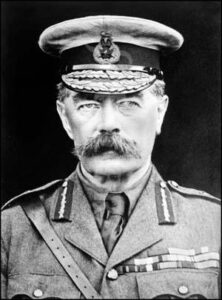

I think most of us have heard the name Hindenburg in some version or another. Whether it’s the airship disaster of 1937; the man himself, Paul von Hindenburg; or the Hindenburg Line of World War I, the name is known. Paul von Hindenburg was born into an aristocratic family on October 2, 1847, in Posen, Prussia, which is present-day Pozna?, Poland. His father was a Prussian military officer-turned-government official, who was granted a title of nobility in 1869; and his mother was the daughter of a doctor.

I think most of us have heard the name Hindenburg in some version or another. Whether it’s the airship disaster of 1937; the man himself, Paul von Hindenburg; or the Hindenburg Line of World War I, the name is known. Paul von Hindenburg was born into an aristocratic family on October 2, 1847, in Posen, Prussia, which is present-day Pozna?, Poland. His father was a Prussian military officer-turned-government official, who was granted a title of nobility in 1869; and his mother was the daughter of a doctor.

Hindenburg joined the Prussian army when he was 19, amid the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, which was also referred to as the Seven Weeks’ War…a significant event leading up to the unification of Germany. Hindenburg fulfilled the role of a staff officer in the Franco-Prussian War from 1870 to 1871 and ultimately rose to the rank of lieutenant general.

After a long military career, Hindenburg retired in 1911, at the age of 64. Then, with the onset of World War I in 1914, he was recalled to active service. As commander of the Eighth Army, he was elevated to the rank of field marshal and achieved a string of victories over the Russians on the Eastern Front, cementing his status as a national hero. One battle that stands out was the Battle of Tannenberg in Poland. Under his command, alongside his chief of staff General Erich Ludendorff, it became one of Germany’s most decisive triumphs of the war.

Anna von der Golz wrote a book called Hindenburg, in which she is quotes as saying, “Soon after the outbreak of war Hindenburg became Germany’s major symbol of victory against the enemy and of unity at home–a function traditionally performed by the Emperor in wartime, or perhaps on occasion by the Chief of the General Staff, but certainly not by the commander of a single German army.”

The phrase “Hindenburg will sort it out,” swiftly turned into a catchphrase, and depictions of the field marshal proliferated, she said. Hindenburg was named chief of the German General Staff by Kaiser Wilhelm entrusting him with the army’s command. Still, the Allies still managed to inflict a decisive defeat.

Following Germany’s defeat in World War I, Hindenburg retired from the military for the second time and entered politics. In 1925, at the age of 77, the “Victor of Tannenberg” was elected as the president of the democratic Weimar Republic (1919-1933), becoming Germany’s second president. He was re-elected in 1932.

In an effort to stabilize the region after the war and the harsh conditions of the Armistice of Compiègne, Hindenburg resorted to issuing presidential emergency decrees, not a real good move on his part. Nevertheless, it was permitted by the nation’s constitution in times of disturbance and economic distress. These decrees enabled him to bypass the German parliament’s consent, suppress his political adversaries, curtail free speech and other civil liberties, and permit military leaders to dictate foreign policy.

Hindenburg was initially a critic of Hitler and the Nazi Party, so at first, he declined to bestow upon Hitler the chancellorship he sought. However, under pressure from his conservative advisors and due to the rising influence of the Nazi Party, he eventually named Hitler as chancellor, reassured by his advisors that they could contain the Nazi program. That was likely his biggest mistake. Hitler swiftly utilized Hindenburg’s decree powers to enact several mandates, including the 1933 Reichstag Fire Decree, the Enabling Act, and the Law for the Protection of the People and the State.

As Hindenburg’s health declined, his appointment effectively granted Hitler dictatorial powers. Upon Hindenburg’s death at age 86 on August 2, 1934, Hitler declared himself the Führer of Germany. Hindenburg was buried alongside his wife, Gertrud von Sperling, who passed away in 1921, at the Tannenberg war memorial in Prussia. Their remains were later transferred to Saint Elizabeth Church in Marburg, Germany, in 1946.