History

As disastrous fires go, the Great Baltimore Fire comes in historically as the third worst conflagration in an American city, surpassed only by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906. There were other major urban disasters that were comparable in cost, but not fires. These were the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 and most recently, Hurricane Katrina that hit New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico coast in August 2005.

As disastrous fires go, the Great Baltimore Fire comes in historically as the third worst conflagration in an American city, surpassed only by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906. There were other major urban disasters that were comparable in cost, but not fires. These were the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 and most recently, Hurricane Katrina that hit New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico coast in August 2005.

On February 7, 1904, a small fire was reported at the John Hurst and Company building on West German Street at Hopkins Place, The site is currently the Royal Farms Arena in the western part of downtown Baltimore. The fire started at about 10:48am, and quickly spread. It wasn’t long before the fire surpassed the ability of the city’s firefighting resources, and calls for help were telegraphed to other cities. By 1:30pm, units from Washington, DC were arriving on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad at Camden Street Station. Officials decided to use a firebreak in an effort to halt the fires progression. They dynamited buildings around the existing fire. Unfortunately, this tactic was unsuccessful. The fire continued to rage and spread until it was finally brought under control about 5:00pm on February 8, 1904.

In the end, the fire engulfed a large portion of the city that evening. The culprit for starting the fire is believed to have been a discarded cigarette in the basement of the Hurst Building. When the fire was finally out after burning for 31 hours, an 80-block area of downtown Baltimore, stretching from the waterfront to Mount Vernon on Charles Street, had been destroyed. More than 1,500 buildings were completely leveled, and some 1,000 severely damaged, bringing property loss from the disaster to an estimated $100 million. No lives were lose in this disaster…miraculously, although some reports did claim one man died, but that was not confirmed. The fire raged from North Howard Street in the west and southwest, the flames spread north through the retail shopping area as far as Fayette Street and began moving eastward, pushed along by the prevailing winds. Amazingly, it narrowly missed the new 1900 Circuit Courthouse…now known as the Clarence M. Mitchell, Jr. Courthouse. The fire passed the historic Battle Monument Square from 1815 to 1827 at North Calvert Street, and the quarter-century-old  Baltimore City Hall of 1875 on Holliday Street; and finally spread further east to the Jones Falls stream which divided the downtown business district from the old East Baltimore tightly-packed residential neighborhoods of Jonestown…also known as Old Town and newly named Little Italy.” The fire burned as far south as the wharves and piers lining the north side of the old “Basin,” now the “Inner Harbor” of the Northwest Branch of the Baltimore Harbor and Patapsco River facing along Pratt Street. Also spared was Baltimore’s domed City Hall, built in 1867. The Great Baltimore Fire was the most destructive fire in the United States since the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, It destroyed most of the city and caused an estimated $200 million in property damage.

Baltimore City Hall of 1875 on Holliday Street; and finally spread further east to the Jones Falls stream which divided the downtown business district from the old East Baltimore tightly-packed residential neighborhoods of Jonestown…also known as Old Town and newly named Little Italy.” The fire burned as far south as the wharves and piers lining the north side of the old “Basin,” now the “Inner Harbor” of the Northwest Branch of the Baltimore Harbor and Patapsco River facing along Pratt Street. Also spared was Baltimore’s domed City Hall, built in 1867. The Great Baltimore Fire was the most destructive fire in the United States since the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, It destroyed most of the city and caused an estimated $200 million in property damage.

I think we have all heard of the Bermuda Triangle, where planes and ships have mysteriously gone missing in the Atlantic Ocean for decades, but most people are not aware that there is a similar place in Alaska and one in Nevada. The Nevada Triangle lies in a region of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in Nevada and California. In that area, some 2,000 planes have been lost in the last 60 years. That may not seem significant, but when you break it down, it is about 3 crashes/disappearances a every month of those 60 years. The Nevada Triangle is more than 25,000 miles of mountain desert. It is a remotely populated area, and many of the crash sites have never found.

I think we have all heard of the Bermuda Triangle, where planes and ships have mysteriously gone missing in the Atlantic Ocean for decades, but most people are not aware that there is a similar place in Alaska and one in Nevada. The Nevada Triangle lies in a region of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in Nevada and California. In that area, some 2,000 planes have been lost in the last 60 years. That may not seem significant, but when you break it down, it is about 3 crashes/disappearances a every month of those 60 years. The Nevada Triangle is more than 25,000 miles of mountain desert. It is a remotely populated area, and many of the crash sites have never found.

The triangle location is roughly defined as spanning from Las Vegas, Nevada; to Fresno, California; to Reno, Nevada. Of course, notoriously located in this wilderness area is the mysterious, top-secret Area 51…adding to the mystery of these disappearances. Along with the dozens of conspiracy theories which include UFO’s and paranormal activity that surrounds the air force base, similar theories have long been considered regarding the Nevada Triangle. Throughout these many years, many of the missing planes were flown by experienced pilots and disappeared under mysterious circumstances, with the wreckage never found. I don’t buy into most conspiracy theories, and I don’t know what I think of this situation either, but when you look at the statistics an undeniable picture of strangeness does seem to present itself.

Probably one of the most famous cashes of our current time is that of record-setting aviator, sailor, and adventurer, Steve Fossett on September 3, 2007. Fossett, who was flying a single-engine Bellanca Super Decathlon over Nevada’s Great Basin Desert, took off and never returned. Search crews combed the area for a month, before the search was called off and on February 15, 2008, Fossett was declared dead. Then on September 29th, 2008, Fossett’s identification cards were discovered in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California by a hiker. Of course, that reactivated the search, and a few days later, the crash site was discovered, located approximately 65 miles from where the aviator initially took off. Initially, no remains were found, but two bones were later recovered a half mile from the crash site which were found to have belonged to Steve Fossett. It is assumed that his body was carried of by wild animals, hence the scattered bones.

One of the earliest incidents of planes lost in the “Triangle” dates back 70 years when a B-24 bomber crashed in the Sierra Nevada mountains in 1943. The bomber, took off on December 5th, piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Willis Turvey and co-piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Robert M Hester. The plane carried four other crew members including 2nd Lieutenant William Thomas Cronin, serving as navigator; 2nd Lieutenant Ellis H Fish, bombardier; Sergeant Robert Bursey, engineer; and Sergeant Howard A Wandtke, radio operator. A routine night training mission, the plane took off from Fresno, California’s Hammer Field destined to Bakersfield, California to Tucson, and then was scheduled to return. The next day an extensive search mission began when nine B-24 Bombers were sent out to find the missing plane. The search was unsuccessful, and also brought about another mystery, when one of the search bombers went missing. On the morning of December 6, 1943, Squadron Commander Captain William Darden lifted off along with eight other B-24s. Captain Darden, his airplane, and remaining crew would not be seen again until 1955, at which point the Huntington Lake reservoir was drained for repairs to the dam. I suppose that all of the missing planes are somewhere, and might still be discovered someday, bit it is a vast area, and it is almost impossible to search all of it. Even with information concerning Captain Darden and his B-24, by survivors who bailed out at the captains orders, that the captain tried to land in a clearing that ended up being a half frozen lake, it still took twelve years to locate the plane.

The father of the original B-24’s co-pilot never gave up the search, although he was unsuccessful and died of a heart attack in 1959, about 14 years after the crash. One year after Clinton Hester passed away, the wreckage was found in July 1960 by to United States Geological Survey researchers who were working in a remote section of the High Sierra, west of LeConte Canyon in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. There, they found airplane wreckage in and near an unnamed lake. Later, Army investigators revealed the wreckage to be that of the first missing bomber piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Willis Turvey and co-piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Robert M. Hester. The lake is now known as Hester Lake.

It would seem that the Kings Canyon National Park area is a tough one to search, and seems to hold the key to may of the missing planes. As odd as some of these events sound, I find it hard to believe that they could have just disappeared. Still, I’m no expert in the matter, and these may not have been the only time something or someone just went missing. I am reminded of Enoch in the Bible, “And Enoch walked with God and disappeared because God took him.” Genesis 5:24. Whatever may have happened in these cases of missing planes, some of which we may never know, and some that may remain a mystery for years; the fact remains that this is a very difficult area to search, and so we really just don’t know. “Conspiracy theorists have long claimed the reason so many flights have disappeared is connected to the presence Area 51, where the US Air Force is known to test secret prototype aircraft. But, many experts believe the disappearances can be attributed to the areas geography and atmospheric conditions. The Sierra Nevada mountains run perpendicular to the Jet Stream, or high Pacific winds, which conspire with the sheer, high altitude peaks and wedge-shaped range to create volatile, unpredictable winds and downdrafts. This weather phenomenon is sometimes called the “Mountain

Wave” where planes are seemingly ripped from the air and crashed to the ground.” Of course, many experts believe they are pilot error, inexperienced pilots getting caught in turbulence, and the disorienting mountain terrain. I suppose that is possible, but that is a lot of cases over the past 60 years. Then again, not every plane that flies over the area disappears either, so who am I to say.

Wave” where planes are seemingly ripped from the air and crashed to the ground.” Of course, many experts believe they are pilot error, inexperienced pilots getting caught in turbulence, and the disorienting mountain terrain. I suppose that is possible, but that is a lot of cases over the past 60 years. Then again, not every plane that flies over the area disappears either, so who am I to say.

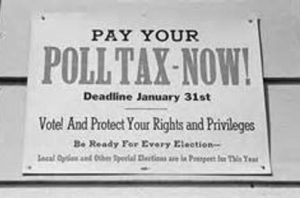

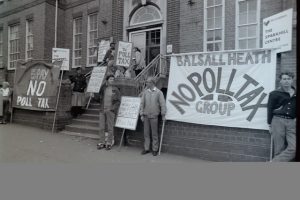

Those of us living today, might not have heard of a thing called a Poll Tax, but it was a very real thing, and with the election process just behind us, I think this might be something worth hearing. The Poll Tax was also known as a head tax or a capitation tax (meaning a tax for a head count). When I first thought about this particular tax, I thought well, maybe that kind of a tax could have ensured a fair election, but really, the opposite is true. While the head tax was considered an important source of revenue for many governments, from ancient times until the 19th century, in the United States at least; voting poll taxes (whose payment was a precondition to voting in an election) have been used to disenfranchise impoverished and minority voters (especially under Reconstruction). I find that absolutely unbelievable. In this nation in most election years, we have to practically beg people to get out and vote. Charging them money for it would all but insure a poor turnout. It would also insure that only those well enough off to be able to “throw money” at an election would be able to vote. Now that is truly appalling.

Those of us living today, might not have heard of a thing called a Poll Tax, but it was a very real thing, and with the election process just behind us, I think this might be something worth hearing. The Poll Tax was also known as a head tax or a capitation tax (meaning a tax for a head count). When I first thought about this particular tax, I thought well, maybe that kind of a tax could have ensured a fair election, but really, the opposite is true. While the head tax was considered an important source of revenue for many governments, from ancient times until the 19th century, in the United States at least; voting poll taxes (whose payment was a precondition to voting in an election) have been used to disenfranchise impoverished and minority voters (especially under Reconstruction). I find that absolutely unbelievable. In this nation in most election years, we have to practically beg people to get out and vote. Charging them money for it would all but insure a poor turnout. It would also insure that only those well enough off to be able to “throw money” at an election would be able to vote. Now that is truly appalling.

It is my understanding that originally the “poll tax” or maybe more correctly, head tax was not about an election, but more like the census. It even has Biblical roots…Mary and Joseph went to Bethlehem to be counted and pay their taxes to Caesar Augustus. This was the first of the head taxes. The tax might have been originally a way to bring in revenue. The poll taxes that followed, in most cases, were purely discriminatory.  These latter poll taxes ensured that only wealthy people got the chance to cast their vote…thereby putting in candidates that those in charge wanted.

These latter poll taxes ensured that only wealthy people got the chance to cast their vote…thereby putting in candidates that those in charge wanted.

While the Poll Tax might have been a way to bring in money for governments, it seems to me that it could also be a way to make sure that the people vote for the candidate the government wants. Those who might have voted for change to improve the situation in their own neighborhoods, towns, cities, and states, were usually the poorer people, but they couldn’t vote for someone who could help, because they didn’t have the money. Many of these people were minorities. Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments from ancient times until the 19th century. In the United Kingdom, poll taxes were levied by the governments of John of Gaunt in the 14th century, Charles II in the 17th and Margaret Thatcher in the 20th century. By their very nature, poll taxes are considered very regressive taxes, are usually very unpopular and have been implicated in many uprisings.

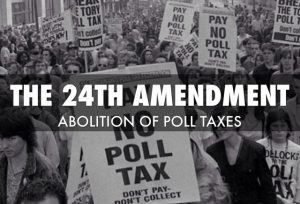

On August 27, 1962, the Twenty-fourth Amendment (Amendment XXIV) of the United States Constitution was proposed. The Twenty-fourth Amendment prohibits both Congress and the states from conditioning the right to vote in federal elections on payment of a poll tax or other types of tax. The amendment was ratified by the states on January 23, 1964. When the 24th Amendment was ratified in 1964, five states still retained a poll tax. Those states were Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia. These states continues the practice  even though the amendment prohibited requiring a poll tax for voters in federal elections. Finally, in 1966 the US Supreme Court ruled 6–3 in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, that poll taxes for any level of elections were unconstitutional. The ruling stated that the poll tax violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Further litigation related to potential discriminatory effects of voter registration requirements has generally been based on application of this clause. Those of us living today, might not have heard of a thing called a Poll Tax, but it was a very real thing, and with the election process just behind us, I think this might be something worth hearing. The Poll Tax was also known as a head tax or a capitation tax (meaning a tax for a head count).

even though the amendment prohibited requiring a poll tax for voters in federal elections. Finally, in 1966 the US Supreme Court ruled 6–3 in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, that poll taxes for any level of elections were unconstitutional. The ruling stated that the poll tax violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Further litigation related to potential discriminatory effects of voter registration requirements has generally been based on application of this clause. Those of us living today, might not have heard of a thing called a Poll Tax, but it was a very real thing, and with the election process just behind us, I think this might be something worth hearing. The Poll Tax was also known as a head tax or a capitation tax (meaning a tax for a head count).

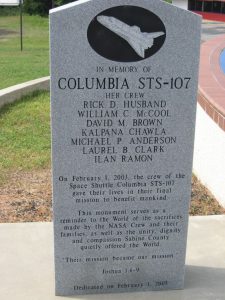

Anyone who knows anything about the space program, knows about the disasters that have come out of it…or at least some of them. One of those disasters, the breakup of Space Shuttle Columbia, happened 18 years ago today, February 1, 2003. The breakup upon re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere took the lives of all seven astronauts on board, in a way that we can only imagine as horrific. The best we can hope for following the tragedy is that the astronauts were killed instantly, so they did not suffer in what followed the breakup. It was a horrible day for the United States, and for NASA, but what followed that terrible disaster was a truly remarkable phenomena.

Anyone who knows anything about the space program, knows about the disasters that have come out of it…or at least some of them. One of those disasters, the breakup of Space Shuttle Columbia, happened 18 years ago today, February 1, 2003. The breakup upon re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere took the lives of all seven astronauts on board, in a way that we can only imagine as horrific. The best we can hope for following the tragedy is that the astronauts were killed instantly, so they did not suffer in what followed the breakup. It was a horrible day for the United States, and for NASA, but what followed that terrible disaster was a truly remarkable phenomena.

It is tragedies like the Space Shuttle Columba that bring out the true American spirit. Feelings are set aside, and you suddenly see people hugging each other to comfort them. Columbia broke up in the skies of East Texas on its way back home to Kennedy Space Center. Almost immediately after losing the craft, the NASA world and many others, converged on the small town of Hemphill, Texas. Everyone wanted to help, and many who were not called into service, volunteered. The Space Program had become so commonplace and so routine that such an event came as a horrible shock to this nation and to the world. Suddenly we were glued to our television sets or radios, waiting for news, hoping against hope that there might be survivors, but knowing that it was clearly not possible.

It wasn’t just the NASA teams who showed up for this tragic event. Restaurants gave free meals to the workers. People reported anything they found so it could be documented and processed. The townspeople were there to offer comfort to those in need, because lets face it, these astronauts were members of the NASA family, and NASA (as well as the rest of the nation) was in mourning. As time went on, more and more searchers converged on Hemphill and the surrounding area. The local heroes continued to step up, giving any kind of support needed. This might seem like a small feat to some people, but this search went on for three months. That is a long time to care for so many in such a small town, but it was desperately needed, and

gratefully received. After a long, drawn-out search, the teams had found all the seemed to be going to find, and almost as quickly as they had arrived, the teams were gone, and the small town of Hemphill, Texas was quiet again, but it would never be the same again. Three months in 2003 had changed it forever. The people who lived there in that time will never forget what they did back then, and we will never forget what they did. It was an awesome feat of kindness and love for our fellow man.

gratefully received. After a long, drawn-out search, the teams had found all the seemed to be going to find, and almost as quickly as they had arrived, the teams were gone, and the small town of Hemphill, Texas was quiet again, but it would never be the same again. Three months in 2003 had changed it forever. The people who lived there in that time will never forget what they did back then, and we will never forget what they did. It was an awesome feat of kindness and love for our fellow man.

On January 31, 1917, at the height of World War I, Germany announced that they would renew the use of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic Ocean. The German torpedo-armed submarines, known as U-Boats, prepared to attack any and all ships operating in the Atlantic, including civilian passenger carriers, which were said to have been sighted in war-zone waters. They were prepared to attack without a second thought, whether they were innocent civilians or not. Unleashing the U-Boats was almost like unleashing terrorists, because the U-Boats were an invisible enemy. Yes, the could be seen, but beneath the surface of the water, they could easily hide in the murky darkness, unleashing their torpedoes to go streaking through the water. The first sign of danger was when the doomed ship watchmen saw the dreaded white streak coming at them through the water. There was no time to take evasive action. The ship could not move that fast, and it could not turn on a dime. They were sitting ducks.

On January 31, 1917, at the height of World War I, Germany announced that they would renew the use of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic Ocean. The German torpedo-armed submarines, known as U-Boats, prepared to attack any and all ships operating in the Atlantic, including civilian passenger carriers, which were said to have been sighted in war-zone waters. They were prepared to attack without a second thought, whether they were innocent civilians or not. Unleashing the U-Boats was almost like unleashing terrorists, because the U-Boats were an invisible enemy. Yes, the could be seen, but beneath the surface of the water, they could easily hide in the murky darkness, unleashing their torpedoes to go streaking through the water. The first sign of danger was when the doomed ship watchmen saw the dreaded white streak coming at them through the water. There was no time to take evasive action. The ship could not move that fast, and it could not turn on a dime. They were sitting ducks.

The vast majority of people of the United States favored neutrality when it came to World War I. So when the war erupted in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson pledged the stay neutral. The problem was that Britain was one of America’s closest trading partners. That created serious tension between the United States and Germany, when Germany attempted a blockade of the British isles. Several US ships traveling to Britain were damaged or sunk by German mines and, in February 1915, Germany announced unrestricted warfare against all ships, neutral or otherwise, that entered the war zone around Britain. One month later, Germany announced that a German cruiser had sunk the William P. Frye, a private American merchant vessel that was transporting grain to England when it disappeared. President Wilson was outraged, but the German government apologized, calling the attack an unfortunate mistake. That didn’t stop their reign of terror, however. In November they sank an Italian liner without warning, killing 272 people, including 27 Americans. Public opinion concerning the war, and the stand of the United States in it began to change. It was time for the United States to get into World War I.

The Germans were far in advance of other nations when it came to submarines. The U-boat was 214 feet long, carried 35 men and 12 torpedoes, and could travel underwater for two hours at a time. In the first few years of World War I, the U-boats took a terrible toll on Allied shipping. In early May 1915, several New York newspapers had to publish a warning by the German embassy in Washington that Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones did so at their own risk. The announcement was placed on the same page as an advertisement for the imminent sailing of the British-owned Lusitania ocean liner from New York to Liverpool. I’m sure they had hoped that people would heed the warning, but many people boarding the Lusitania either didn’t take notice of the warning or they didn’t see it. On May 7, the Lusitania was torpedoed without warning just off the coast of Ireland. Of the 1,959 passengers, 1,198 were killed, including 128 Americans. The Germans had proven once again that they were ruthless and conniving. Following the sinking of the Lusitania The German government accused the Lusitania was carrying munitions. The US demanded an end to German attacks on unarmed passenger and merchant ships, and full repayment for the loss.

Following the sinking of the Lusitania the German government accused the Lusitania was carrying munitions. The US demanded an end to German attacks on unarmed passenger and merchant ships, and full repayment for the loss. Germany countered with a pledge to see to the safety of passengers before sinking unarmed vessels in August 1915. All that changed by January 1917, when Germany, determined to win its war of attrition against the Allies, announced the resumption of unrestricted warfare. Three days later, the United States broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, who, just hours later sunk the American liner Housatonic. None of the 25 Americans on board were killed and they were picked up by a British steamer.

On February 22, Congress passed a $250 million arms-appropriations bill intended to ready the United States for war. British authorities gave the US ambassador to Britain a copy of what has become known as the “Zimmermann Note,” a coded message from German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann to Count Johann von Bernstorff, the German ambassador to Mexico. In the telegram, intercepted and deciphered by British intelligence, Zimmermann stated that, in the event of war with the United States, Mexico should be asked to  enter the conflict as a German ally. In return, Germany would promise to restore to Mexico the lost territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. On March 1, the outraged US State Department published the note and America was galvanized against Germany once and for all. In late March, Germany sank four more US merchant ships. President Wilson appeared before Congress and called for a declaration of war against Germany on April 2nd. On April 4th, the Senate voted 82 to six to declare war against Germany. Two days later, the House of Representatives endorsed the declaration by a vote of 373 to 50 and America formally entered World War I. They were after that invisible enemy, and they were determined to find it and destroy it.

enter the conflict as a German ally. In return, Germany would promise to restore to Mexico the lost territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. On March 1, the outraged US State Department published the note and America was galvanized against Germany once and for all. In late March, Germany sank four more US merchant ships. President Wilson appeared before Congress and called for a declaration of war against Germany on April 2nd. On April 4th, the Senate voted 82 to six to declare war against Germany. Two days later, the House of Representatives endorsed the declaration by a vote of 373 to 50 and America formally entered World War I. They were after that invisible enemy, and they were determined to find it and destroy it.

Captain George Vancouver, a British Officer, commanded the HMS Discovery and its accompanying ships on an exploratory voyage of the Pacific Northwest, between the years of 1791 and 1794. Vancouver and his crew were privileged to be the first to see places like Mount Saint Helens and the first to explore the Puget Sound. Their goal was to explore every bay and outlet in the region…following the coasts of Oregon and Washington. Men were sent in smaller boats to explore the Columbia River and enter the strait of Juan de Fuca.

Captain George Vancouver, a British Officer, commanded the HMS Discovery and its accompanying ships on an exploratory voyage of the Pacific Northwest, between the years of 1791 and 1794. Vancouver and his crew were privileged to be the first to see places like Mount Saint Helens and the first to explore the Puget Sound. Their goal was to explore every bay and outlet in the region…following the coasts of Oregon and Washington. Men were sent in smaller boats to explore the Columbia River and enter the strait of Juan de Fuca.

The larger ships, including the Chatham…the Armed Tender of the HMS Discovery, often anchored in the safe harbors, while the smaller vessels explored the many channels and rivers along the coast. On April 29, 1792, the ships entered the Straits of Juan de Fuca and anchored in the calm waters of Discovery Bay. While the ships stayed in the bay…using it as a base, Vancouver and his men explored the waters of Admiralty Inlet and Hood Canal. After several weeks of exploring, the Chatham began to sail north across the Straits of Juan de Fuca to explore the San Juan and Lopez Islands. After successfully exploring the islands, the Chatham sailed southward in May to rejoin the HMS Discovery and continue their explorations south. They moved the explorations south, as far as Commencement Bay in Tacoma, before turning around and returning north, where they hoped that the waters were going to be safer.

When the ships arrived at the Puget Sound, a storm was raging, accompanied by severe currents and tides. While crossing an unknown channel, the Chatham was caught by a flood tide and swept away helpless. In an effort to slow her progress, the crew dropped her stream anchor. Unfortunately, the strain was too much and the cable snapped. Amazingly, the Chatham survived, but the sweep of the waters did not locate the lost anchor, so the ship rejoined the HMS Discovery.

When the ships arrived at the Puget Sound, a storm was raging, accompanied by severe currents and tides. While crossing an unknown channel, the Chatham was caught by a flood tide and swept away helpless. In an effort to slow her progress, the crew dropped her stream anchor. Unfortunately, the strain was too much and the cable snapped. Amazingly, the Chatham survived, but the sweep of the waters did not locate the lost anchor, so the ship rejoined the HMS Discovery.

Vancouver’s journal entry for June 9, 1792 read, “We found tides here extremely rapid, and on the 9th in endeavoring to get around a point to the Bellingham Bay we were swept leeward of it with great impetuosity. We let go the anchor in 20 fathoms but in bringing it up such was the force of the tide that we parted the cable. At slack water we swept for the anchor but could not get it. After several fruitless attempts, we were at last obliged to leave it.”

These days, the anchor would be a treasure of great value, which motivated a company called Anchor Ventures,  LLC of Seattle to initiate a search of not the Cannel, but rather off Whidbey Island’s northwestern shore. Their bet that the Chatham wasn’t with the Discovery at the time of the storm apparently paid off. Anchor Ventures pulled up what they believe to be the long lost anchor in 2014. Since then, the team has been trying to prove its identity. Skeptics aren’t so sure that this is the right anchor, because they say it is heavier than those of the late 1700s. That said, the question remains. Is the anchor still there, or did they jump to conclusions. It’s hard to say, and proof will be tough to find. I think it is not likely that they found the right anchor…especially looking in the wrong place.

LLC of Seattle to initiate a search of not the Cannel, but rather off Whidbey Island’s northwestern shore. Their bet that the Chatham wasn’t with the Discovery at the time of the storm apparently paid off. Anchor Ventures pulled up what they believe to be the long lost anchor in 2014. Since then, the team has been trying to prove its identity. Skeptics aren’t so sure that this is the right anchor, because they say it is heavier than those of the late 1700s. That said, the question remains. Is the anchor still there, or did they jump to conclusions. It’s hard to say, and proof will be tough to find. I think it is not likely that they found the right anchor…especially looking in the wrong place.

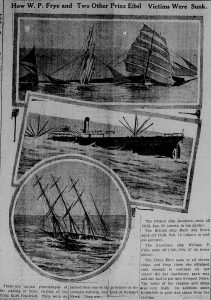

As is common with ships, the William P. Frye was a four-masted steel barque named after a US Republican politician of the same name, from the state of Maine. The ship was built by Arthur Sewall and Co of Bath, Maine in 1901. For a time, the ship had a great run…until 1915, that is. The ship sailed from Seattle, Washington on November 4, 1914, with a cargo of 189,950 US bushels of wheat. The ship and its cargo were bound for Queenstown, Falmouth, or Plymouth in the United Kingdom. In 1915 the United Kingdom was at war with Imperial Germany, but the United States was not enter the war yet and was officially neutral. It was early in the war, but that doesn’t make it any less dangerous to sail the high seas.

As is common with ships, the William P. Frye was a four-masted steel barque named after a US Republican politician of the same name, from the state of Maine. The ship was built by Arthur Sewall and Co of Bath, Maine in 1901. For a time, the ship had a great run…until 1915, that is. The ship sailed from Seattle, Washington on November 4, 1914, with a cargo of 189,950 US bushels of wheat. The ship and its cargo were bound for Queenstown, Falmouth, or Plymouth in the United Kingdom. In 1915 the United Kingdom was at war with Imperial Germany, but the United States was not enter the war yet and was officially neutral. It was early in the war, but that doesn’t make it any less dangerous to sail the high seas.

When the ship was near the coast of Brazil, the Imperial German Navy raider SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich overtook the William P. Frye on January 27, 1915. The Germans stopped and boarded the ship. I can’t imagine what it must have been like to have an enemy navy detain a ship I was on. You just never know what they are going to do. The William P. Frye was owned by the United States, and so a neutral ship. The ship should have been treated  as neutral. The problem the William P. Frye had is that the cargo was deemed a legitimate war target because the Germans believed it was bound for Britain’s armed forces. In reality, even detaining the ship was probably an act of war, but that never seemed to bother the Germans anyway.

as neutral. The problem the William P. Frye had is that the cargo was deemed a legitimate war target because the Germans believed it was bound for Britain’s armed forces. In reality, even detaining the ship was probably an act of war, but that never seemed to bother the Germans anyway.

Upon making his decision that the William P. Frye was a legitimate target, the captain of SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich, Max Thierichens, ordered that William P. Frye’s cargo of wheat be thrown overboard. The captain and crew began to comply, most likely begrudgingly, and when the orders were not followed fast enough, he took the ship’s crew and passengers prisoner. Then he ordered the ship scuttled on January 28, 1915. The William P. Frye was the first American vessel sunk during World War I, and the United States wasn’t even in the war yet. The  owners of the ship, Arthur Sewall and Co, wanted damages for the sinking of the ship and presented a claim for $228,059.54, which would total $5,763,800 today. In all, the SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich scuttled eleven ships during their reign of terror. They stole coal and gold from their victims, which kept them going for a while, until they developed engine trouble.

owners of the ship, Arthur Sewall and Co, wanted damages for the sinking of the ship and presented a claim for $228,059.54, which would total $5,763,800 today. In all, the SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich scuttled eleven ships during their reign of terror. They stole coal and gold from their victims, which kept them going for a while, until they developed engine trouble.

In another act of war, Thierichens took the passengers and the crew captive. Women and children, were part of approximately 350 people taken prisoner from eleven different ships that SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich’s crew had searched and destroyed. I suppose the possible act of war was somewhat forgiven when all 350 were released on March 10, 1915, when the German raider had engine trouble, and docked Newport News, Virginia, but then again, what else could they do with them. Nevertheless, an outraged American government forced the Germans to apologize for the sinking, and of course, the SMS Prinz Eitel Friedrich was detained in port.

As the Third Reich was losing its war against the world, German General Friedrich Paulus, who was commander in chief of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad, urgently requests permission from Adolf Hitler to surrender his position there. Paulus knew they had no chance, but Hitler refused. Of course, we all know that Hitler was insane. He would make his men fight to the death when there was no hope of winning the battle.

As the Third Reich was losing its war against the world, German General Friedrich Paulus, who was commander in chief of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad, urgently requests permission from Adolf Hitler to surrender his position there. Paulus knew they had no chance, but Hitler refused. Of course, we all know that Hitler was insane. He would make his men fight to the death when there was no hope of winning the battle.

Stalingrad was a prized strategic area, and the battle to take the city began in the summer of 1942. German forces assaulted the city, which was a major industrial center, but they had misjudged the Soviets. Despite repeated attempts and having pushed the Soviets almost to the Volga River in mid-October, as well as encircling Stalingrad, the 6th Army, under Paulus, and part of the 4th Panzer Army could not break past the adamantine defense of the Soviet 62nd Army. As their resources diminished. The Germans suffered diminishing resources, partisan guerilla attacks, and the cruelty of the Russian winter, all of which began to take their toll on the Germans. The Soviets made their move on November 19, launching a counteroffensive that began with a massive artillery bombardment of the German position. The assault began when the Soviets attacked the weakest link in the German force-inexperienced Romanian troops. Soviet soldiers took 65,000 soldiers prisoner that day. Then, the Soviets in a bold strategic move, encircled the enemy and launched pincer movements from north and south simultaneously, just as the Germans were encircling Stalingrad. It was at this point that the Germans should have withdrawn, and Paulus requested permission to withdraw, but Hitler wouldn’t allow it. He told his armies to hold out until they could be reinforced. Fresh troops would not arrive until December, and by then it was too late. The Soviet position was too strong, and the Germans were exhausted. They were out of options.

By January 24, the Soviets had overrun Paulus’ last airfield. His position was indefensible and surrender was the only hope for survival. Paulus urgently requested, “Let us surrender!!” Still, Hitler wouldn’t hear of it: “The 6th Army will hold its positions to the last man and the last round.” Paulus held out until January 31, when he finally surrendered. Of more than 280,000 men under Paulus’ command, half were already dead or dying,

about 35,000 had been evacuated from the front, and the remaining 91,000 were hauled off to Soviet POW camps. Paulus eventually sold out to the Soviets altogether, joining the National Committee for Free Germany and urging German troops to surrender. Testifying at Nuremberg for the Soviets, he was released and spent the rest of his life in East Germany. Hitler was crazy, and his officers knew it, but there was little they could do about it.

about 35,000 had been evacuated from the front, and the remaining 91,000 were hauled off to Soviet POW camps. Paulus eventually sold out to the Soviets altogether, joining the National Committee for Free Germany and urging German troops to surrender. Testifying at Nuremberg for the Soviets, he was released and spent the rest of his life in East Germany. Hitler was crazy, and his officers knew it, but there was little they could do about it.

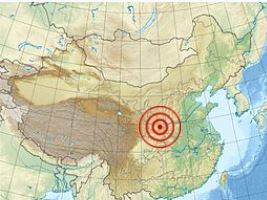

Most of us realize that there are earthquakes going on all the time. Most of them are very small, and often not even felt by anyone. Some are so far out in the ocean that they have little effect of anything. Others are far out in the wilderness or unpopulated areas, and so no one feels them. There are, however, some that are so large and so devastating, that they can never be forgotten. The January 23, 1556 earthquake in Shaanxi, China is just such an earthquake.

Most of us realize that there are earthquakes going on all the time. Most of them are very small, and often not even felt by anyone. Some are so far out in the ocean that they have little effect of anything. Others are far out in the wilderness or unpopulated areas, and so no one feels them. There are, however, some that are so large and so devastating, that they can never be forgotten. The January 23, 1556 earthquake in Shaanxi, China is just such an earthquake.

The earthquake struck Shaanxi late in the evening, and the aftershocks continuing through the following morning. I’m not sure how the scientists can calculate the magnitude years later, but their investigation revealed that the magnitude of the quake was approximately 8.0 to 8.3. That is, by no means, the strongest quake on record, but it struck right in the middle of a densely populated area with poorly constructed buildings and homes, resulting in a horrific death toll. Making buildings earthquake proof in the 1500s was not even a possibility…at least not to the level of the current building codes. Because of that, the death toll was estimated at a staggering 830,000 people. Of course, counting casualties is often imprecise after large-scale disasters, especially prior to the 20th century. Nevertheless, this disaster is still considered the deadliest of all time.

The earthquake’s epicenter was in the Wei River Valley in the Shaanxi Province, near the cities of Huaxian,  Weinan and Huayin. In Huaxian alone, every single building and home collapsed, killing more than half the residents of the city. The death toll there was estimated in the tens of thousands. Similarly, the death toll and economic impact in Weinan and Huayin was also very high. There were places where 60-foot-deep crevices opened in the earth. Serious destruction and death occurred as much as 300 miles away from the epicenter. The earthquake triggered landslides, which also contributed to the massive death toll. Of course, the estimates could be off, but even if the number of deaths caused by the Shaanxi earthquake has been overestimated slightly, it would still rank as the worst disaster in history by a considerable margin.

Weinan and Huayin. In Huaxian alone, every single building and home collapsed, killing more than half the residents of the city. The death toll there was estimated in the tens of thousands. Similarly, the death toll and economic impact in Weinan and Huayin was also very high. There were places where 60-foot-deep crevices opened in the earth. Serious destruction and death occurred as much as 300 miles away from the epicenter. The earthquake triggered landslides, which also contributed to the massive death toll. Of course, the estimates could be off, but even if the number of deaths caused by the Shaanxi earthquake has been overestimated slightly, it would still rank as the worst disaster in history by a considerable margin.

On January 22, 1905, while Russia was well on its way to losing a war against Japan in the Far East, the country found itself engulfed in internal discontent that finally exploded into violence in Saint Petersburg. The horrific events of the day became known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre. Russia had been under the rule of Romanov Czar Nicholas II who had ascended to the throne in 1894. Czar Nicholas II was a weak-willed man who was more concerned that his line would not continue, because his only son Alexis suffered from hemophilia, than he was about the corruption going on in his own administration. Before long, Nicholas fell under the influence of such unsavory characters as Grigory Rasputin, the so-called mad monk. As corruption and an oppressive regime often do, Russia’s imperialist interests in Manchuria at the turn of the century brought on the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904. Behind the scenes, revolutionary leaders, such as the exiled Vladimir Lenin, were gathering forces of socialist rebellion aimed at toppling the czar.

On January 22, 1905, while Russia was well on its way to losing a war against Japan in the Far East, the country found itself engulfed in internal discontent that finally exploded into violence in Saint Petersburg. The horrific events of the day became known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre. Russia had been under the rule of Romanov Czar Nicholas II who had ascended to the throne in 1894. Czar Nicholas II was a weak-willed man who was more concerned that his line would not continue, because his only son Alexis suffered from hemophilia, than he was about the corruption going on in his own administration. Before long, Nicholas fell under the influence of such unsavory characters as Grigory Rasputin, the so-called mad monk. As corruption and an oppressive regime often do, Russia’s imperialist interests in Manchuria at the turn of the century brought on the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904. Behind the scenes, revolutionary leaders, such as the exiled Vladimir Lenin, were gathering forces of socialist rebellion aimed at toppling the czar.

No one wanted to go to war with Japan, and it was going to take some work to drum up support for the unpopular war. The Russian government allowed a conference of the zemstvos to take the lead. A zemstvo was an institution of local government set up during the great emancipation reform of 1861 and carried out in Imperial Russia by Emperor Alexander II of Russia. The first zemstvo laws went into effect in 1864. After the October Revolution the zemstvo system was shut down by the Bolsheviks and replaced with a multilevel system of workers’ and peasants’ councils…the regional governments instituted by Nicholas’s grandfather Alexander II, in St. Petersburg in November 1904. The demands for reform made at this congress went unmet and more radical socialist and workers’ groups decided to take a different tack.

Things exploded on January 22, 1905, when a group of workers led by the radical priest Georgy Apollonovich Gapon marched to the czar’s Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg to make their demands. the imperial forces

immediately opened fire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding hundreds. Strikes and riots broke out throughout the country in outraged response to the massacre. Czar Nicholas responded by promising the formation of a series of representative assemblies, or Dumas, to work toward reform. Unfortunately, he did not follow through with his promise, and internal tension in Russia continued to build over the next decade. As the regime proved unwilling to truly change its repressive ways and radical socialist groups, including Lenin’s Bolsheviks, became stronger, drawing ever closer to their revolutionary goals, the situation grew worse. Finally, more than 10 years later, everything came to a head as Russia’s resources were stretched to the breaking point by the demands of World War I.

immediately opened fire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding hundreds. Strikes and riots broke out throughout the country in outraged response to the massacre. Czar Nicholas responded by promising the formation of a series of representative assemblies, or Dumas, to work toward reform. Unfortunately, he did not follow through with his promise, and internal tension in Russia continued to build over the next decade. As the regime proved unwilling to truly change its repressive ways and radical socialist groups, including Lenin’s Bolsheviks, became stronger, drawing ever closer to their revolutionary goals, the situation grew worse. Finally, more than 10 years later, everything came to a head as Russia’s resources were stretched to the breaking point by the demands of World War I.