History

We seldom think of the “man of the family” being 6 years old, but sometimes circumstances put families in tough situations. Harland Sanders was born September 9, 1890, in Henryville, Indiana to Wilbur David and Margaret Ann (née Dunlevy) Sanders. He was the oldest of their three children, having a younger brother and sister. Sanders’ dad was a gentle and loving man who worked his 80-acre farm, until he broke his leg in a fall. He then worked as a butcher in Henryville for two years. Sanders’ mother was a devout Christian and strict parent, who did her very best to teach her children right from wrong.

We seldom think of the “man of the family” being 6 years old, but sometimes circumstances put families in tough situations. Harland Sanders was born September 9, 1890, in Henryville, Indiana to Wilbur David and Margaret Ann (née Dunlevy) Sanders. He was the oldest of their three children, having a younger brother and sister. Sanders’ dad was a gentle and loving man who worked his 80-acre farm, until he broke his leg in a fall. He then worked as a butcher in Henryville for two years. Sanders’ mother was a devout Christian and strict parent, who did her very best to teach her children right from wrong.

At the tender age of just 6 years, Sanders was forced to take over as man of the family when his father passed away. Often when that happens, the new “position” is just symbolic, but in this case, it certainly wasn’t. Because his mother had to get a job, and Sanders needed to help provide for his younger siblings, so he took jobs as a farmer, salesman, streetcar conductor, and railroad fireman from a young age. His mother got work in a tomato cannery, and the young Sanders was left to look after and cook for his siblings. By the age of seven, he was reportedly skilled with bread and vegetables, and improving with meat.  Times were hard, and the children reportedly foraged for food while their mother was away at work for days at a time. Strange, I know, but remember that things were different in the late 1800s. His formal schooling ended after the seventh grade.

Times were hard, and the children reportedly foraged for food while their mother was away at work for days at a time. Strange, I know, but remember that things were different in the late 1800s. His formal schooling ended after the seventh grade.

His personal life took a hit, because of the stresses and pressure he always seemed to be under. His first wife, wife Josephine King, with whom he had three children: Margaret Josephine, Harland David Jr, and Mildred Marie, left him in 1947, and in 1949, he married his mistress Claudia Ledington-Price…cheating being his biggest failing, in my mind, but things happen. In September 1970 he and his wife were baptized in the Jordan River. He also befriended Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell.

After his son died at the age of 20, Sanders dealt with severe depression. Through this depression, though, he finally found a business he could succeed at: restaurants. At age 40, Sanders was running a service station in Kentucky, where he would also feed hungry travelers. Sanders eventually moved his operation to a restaurant  across the street and featured a fried chicken so notable that he was named a Kentucky colonel in 1935 by Governor Ruby Laffoon. Sanders had to essentially restart the business after roadways had diverted traffic from passing by his restaurant. Nonetheless, his restaurant was eventually rebuilt and his chicken, with its famous new cooking methods, were celebrated. After selling KFC, Sanders would go on to disagree with the direction of the company that still used his face as its advertising, and he even went on to sue his former company. He continued to work for the company until his final days and was reportedly never seen in public without his white suit. Sanders was diagnosed with acute leukemia in June 1980. He died at Louisville Jewish Hospital of pneumonia on December 16, 1980, at the age of 90.

across the street and featured a fried chicken so notable that he was named a Kentucky colonel in 1935 by Governor Ruby Laffoon. Sanders had to essentially restart the business after roadways had diverted traffic from passing by his restaurant. Nonetheless, his restaurant was eventually rebuilt and his chicken, with its famous new cooking methods, were celebrated. After selling KFC, Sanders would go on to disagree with the direction of the company that still used his face as its advertising, and he even went on to sue his former company. He continued to work for the company until his final days and was reportedly never seen in public without his white suit. Sanders was diagnosed with acute leukemia in June 1980. He died at Louisville Jewish Hospital of pneumonia on December 16, 1980, at the age of 90.

These days, we know that washing our hands and our bodies is important to good health. Of course, washing of hands cleans away dirt, germs, and bacteria, as well as many viruses that cause disease, but in the Old West, there were actually people who thought that bathing could actually make you sick, therefore bathing did not occur on a daily basis in the wild west. I’m sure you can imagine just how stinky things got. I suppose that if two people got very near each other, it would be a competition to see who smelled the worst. The reality is that we have all encountered someone who really needed a bath. Most of us would never tell that person that they stunk, but we might really hope that this wasn’t going to be the norm, or we might have to rethink the friendship.

These days, we know that washing our hands and our bodies is important to good health. Of course, washing of hands cleans away dirt, germs, and bacteria, as well as many viruses that cause disease, but in the Old West, there were actually people who thought that bathing could actually make you sick, therefore bathing did not occur on a daily basis in the wild west. I’m sure you can imagine just how stinky things got. I suppose that if two people got very near each other, it would be a competition to see who smelled the worst. The reality is that we have all encountered someone who really needed a bath. Most of us would never tell that person that they stunk, but we might really hope that this wasn’t going to be the norm, or we might have to rethink the friendship.

Women in the old west “bathed” a little more often than the men, if you could exactly call it that. Mostly any daily bathing would consist of a pitcher of water and a washcloth, with the ritual performed in the bedroom of the home. Men on the cattle trail might take a plunge into a watering hole to get “cleaned up”, and quite often the bathing and the laundry would happen at the same time, meaning that a good portion of the body didn’t really get scrubbed up. Nevertheless, it was a good way to rid yourself of that nasty trail dust accumulated on the trail that day…or maybe the prior several days. This type of bathing might also involve armed guards to keep the Indians away.

To make matters worse, when people did bathe, it might be done in the kitchen in a large tub of water, used by the husband first, the mother second, and the children by ages on down the line. As you can imagine, the water got pretty black by the time the youngest child was bathed. Then the water was finally dumped. That is actually where the term, “don’t throw the baby out with the bath water came from.” Sometimes being the youngest had its perks, and other times not so much. Some people would go to public bathhouses, where they might actually have to pay extra for “clean” water, and the guy after them might end up using their water, if he didn’t want to pay the extra fee.

The fact that bathing was inconvenient, and for some, scary, made people sometimes resort to other methods

to rid themselves of the stinky odor. After all, lemon verbena wasn’t just a type of perfume. It helped to mask the odor that would come quickly with infrequent bathing. To make matters worse, people lived in primitive surroundings with lice, fleas and bedbugs, and the smell of their own dirty bodies drew flies and mosquitoes. Hopefully, the lemon verbena would help to keep the pests away…but I wouldn’t count on it really. I don’t think it masked the smell that well.

to rid themselves of the stinky odor. After all, lemon verbena wasn’t just a type of perfume. It helped to mask the odor that would come quickly with infrequent bathing. To make matters worse, people lived in primitive surroundings with lice, fleas and bedbugs, and the smell of their own dirty bodies drew flies and mosquitoes. Hopefully, the lemon verbena would help to keep the pests away…but I wouldn’t count on it really. I don’t think it masked the smell that well.

These days, we not only know that bathing is important to keep the stinky smells away, but it’s important to keep sickness away too. Most of us wouldn’t think of going long without bathing, after all, warding off sickness is important, but warding off that smell is vital!!

A number of presidents and their families have suffered the unthinkable during their time in the White House…the loss of a child. The Adams, Lincoln, Coolidge, and Kennedy families all suffered the loss of a child while in office; the Pierce family lost their last surviving child while en route to Washington to attend Franklin Pierce’s inauguration. John Adams’ grown son Charles died of alcoholism in 1800, shortly after the president lost his reelection bid. Thomas Jefferson’s grown daughter Mary died in 1804, three months after giving birth to her third child. Franklin Pierce lost all three of his sons at an early age. Eleven-year-old Benny, his only surviving child, was killed in a train accident in January 1853, two months before Pierce’s inauguration. Abraham Lincoln lost his son William “Willie” in 1862 in the middle of the Civil War. John F Kennedy lost his son, Patrick two days after he was born on August 7, 1963.

A number of presidents and their families have suffered the unthinkable during their time in the White House…the loss of a child. The Adams, Lincoln, Coolidge, and Kennedy families all suffered the loss of a child while in office; the Pierce family lost their last surviving child while en route to Washington to attend Franklin Pierce’s inauguration. John Adams’ grown son Charles died of alcoholism in 1800, shortly after the president lost his reelection bid. Thomas Jefferson’s grown daughter Mary died in 1804, three months after giving birth to her third child. Franklin Pierce lost all three of his sons at an early age. Eleven-year-old Benny, his only surviving child, was killed in a train accident in January 1853, two months before Pierce’s inauguration. Abraham Lincoln lost his son William “Willie” in 1862 in the middle of the Civil War. John F Kennedy lost his son, Patrick two days after he was born on August 7, 1963.

While it is always horrible when a child dies, whether the parents are famous or not, I find the death of Calvin Coolidge’s son to be among the saddest. While the deaths of these other presidents’ children are sad, little could have been done to change those losses. Calvin Coolidge had two sons, John (the oldest) and Calvin Jr. The boys spent the school year at boarding school, but they spent breaks from boarding school at the White House after he became president in 1923. The oldest son, John was born on September 7, 1906, and Calvin Jr was born on April 13, 1908.

On June 30, 1924, John and Calvin Jr were playing tennis on the courts at the White House. It was a hot summer day…the 91° heat was sweltering. The boys felt that it was too hot for socks, and during the game, Calvin Jr got a blood blister on one of his toes. Within a few days, Calvin Jr was not feeling well. He was diagnosed with blood poisoning…specifically a staphylococcus infection that, at the time, was usually treated with mercury. I’m no doctor, and many advances in the prevention and treatment of infections have been made

over the years. One of the best ways to prevent a staphylococcus infection is proper hygiene…proper, frequent handwashing, and hygiene…or in this case, washing the toe several times a day. The feet are often a breeding ground for bacteria, because they are constantly in a hot, sweaty shoe.

over the years. One of the best ways to prevent a staphylococcus infection is proper hygiene…proper, frequent handwashing, and hygiene…or in this case, washing the toe several times a day. The feet are often a breeding ground for bacteria, because they are constantly in a hot, sweaty shoe.

By July 2, Calvin Jr was limping, running a fever, and had swollen glands in his groin. The blister on his third toe darkened, swelled to the size of a thumbnail, and red lines streaked his legs. This was in the days before antibiotics, and Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin was still four years off. In the words of the attending presidential physician, Calvin Jr was “in trouble.” As Calvin Jr battled sepsis for a week, his father battled despair and really pure panic. It was the kind of agony that only a parent who has lost a child can really understand. Calvin Sr tried to trust that his son was getting “all that medical science” could offer and tried to keep up hope that “he may be better in a few days,” but Calvin Jr passed away at Walter Reed Army General Hospital on July 7, 1924.

President Coolidge and his wife, Grace, were at Calvin Jr’s bedside when he passed, and according to observers, the president’s face resembled “the bleak desolation of cold November rain beating on gray Vermont granite.” Their hearts were broken, and the President often wept, looking out his window where Calvin Jr once played tennis. It was his thought that if he hadn’t been president, his son would have been with them still. He said, “We do not know what would have happened to him under other circumstances, but if I had not been President, he would not have raised a blister on his toe, which resulted in blood poisoning, playing lawn tennis on the South Grounds.”

Starting to live life again after such a horrific loss is never easy, and many people really never make that return

to life. Trying to grieve the loss of a child in such a public setting would be excruciating, and I can’t imagine being forced to live that way. Nevertheless, while much of the wind went out of their sails, the Coolidge family did go forward, as their son would have wanted them to. It’s what a family does. John married and had two daughters…Cynthia and Lydia. The daughters gave President two grandsons and a granddaughter. I think Calvin Jr would be pleased to know that they went forward to live a good life.

to life. Trying to grieve the loss of a child in such a public setting would be excruciating, and I can’t imagine being forced to live that way. Nevertheless, while much of the wind went out of their sails, the Coolidge family did go forward, as their son would have wanted them to. It’s what a family does. John married and had two daughters…Cynthia and Lydia. The daughters gave President two grandsons and a granddaughter. I think Calvin Jr would be pleased to know that they went forward to live a good life.

John F Kennedy never really wanted to be the President of the United States, but his dad wanted one of his sons, and maybe more that one of his sons to be the president, and Joseph Kennedy Sr made that fact well known to his boys. It was always assumed that Joseph Kennedy Jr would be the son to make their dad’s dreams come true, but life doesn’t always go quite the way we planned it.

John F Kennedy never really wanted to be the President of the United States, but his dad wanted one of his sons, and maybe more that one of his sons to be the president, and Joseph Kennedy Sr made that fact well known to his boys. It was always assumed that Joseph Kennedy Jr would be the son to make their dad’s dreams come true, but life doesn’t always go quite the way we planned it.

Joseph Kennedy Jr was the Golden Boy, touted by his father as a child destined to be “the future president of the nation.” He was a skilled athlete, charismatic, and intelligent, he was educated at Harvard and the London School of Economics. His father had groomed him to be president from a very young age, but it was not to be. When World War II drew the United States in, Joe Jr felt called to enlist. He joined the US Navy in 1941, and in 1943 was sent to England, where he flew with the British Naval Command and volunteered to take part in Operation Aphrodite.

Operation Aphrodite and Operation Anvil were the “World War II code names of United States Army Air Forces and United States Navy operations to use Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated PB4Y bombers as precision-guided munitions against bunkers and other hardened/reinforced enemy facilities, such as “Crossbow” operations against German long-range missiles,” specifically the V-3 Super Gun that Hitler was having built. During one of his missions, on August 12, 1944, the explosives aboard a plane flown by Joe Jr detonated early, and the eldest Kennedy son was gone.

As the second-oldest son in the Kennedy family, John F Kennedy was aware that the political aspirations of his father, Joe Sr, rested heavily on his older brother, Joseph P Kennedy Jr. When his brother was killed during WWII, John was also aware that the political torch had just passed to him…and so it did. It didn’t matter that John “was sickly – described by the family patriarch as ‘a very frail boy’ with ‘various troubles’ – and less willing to conform to his father’s will, he had been educated in much the same way as his older brother and was politically astute.” John had always been more of a passive observer. John apparently told one of his friends, “Now the burden falls on me.” Later, in an interview, he recalled what it was like to be shifted into his father’s spotlight, saying, “It was like being drafted. My father wanted his oldest son in politics. ‘Wanted’ isn’t the right word. He demanded it. You know my father.”

By 1947, John Kennedy was a member of the US Congress, the first office he held as he began his journey to becoming the President of the United States in 1960. His father was very determined and would stop at nothing to be able to say, “my son the President of the United States.” He also wanted his other sons, Robert and Ted to be in politics as well. Joe Sr’s “push of his sons” really was the indirect cause of the deaths of John and Robert, in my opinion. Of course, there were other factors, as we all know, but for them, being thrust into the spotlight did place a target on their backs. I don’t know if Robert and Ted were originally interested in politics, but the influence of their dad had to have played a big part in their future political lives.

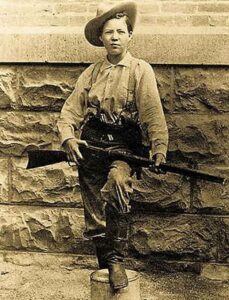

Pearl Hart was born Pearl Taylor in 1871, in the Canadian village of Lindsay, Ontario. Her parents were both religious and affluent, which allowed them to provide their daughter with the best available education. At the age of 16 and a bit of a rebel, she was enrolled in a boarding school where she fell in love with a young man named Hart, who has been variously described as “a rake, drunkard, and/or gambler.” That reputation didn’t deter Pearl and before long, the couple eloped, but Pearl soon discovered that her new husband was abusive and left him to return to her mother.

Pearl Hart was born Pearl Taylor in 1871, in the Canadian village of Lindsay, Ontario. Her parents were both religious and affluent, which allowed them to provide their daughter with the best available education. At the age of 16 and a bit of a rebel, she was enrolled in a boarding school where she fell in love with a young man named Hart, who has been variously described as “a rake, drunkard, and/or gambler.” That reputation didn’t deter Pearl and before long, the couple eloped, but Pearl soon discovered that her new husband was abusive and left him to return to her mother.

One would have thought that she would have learned her lesson and changed her ways before her future life of crime got started, but she chose to become an American Old West outlaw. Pearl Hart gained notoriety just before the turn of the 20th century as a female stagecoach robber. She cut her hair short, dressed in men’s clothing. She actually committed one of the last recorded stagecoach robberies in the United States, and her crime gained notoriety primarily because of her gender. To find out that a woman of that era was brave enough to pull off a stagecoach robbery was very unusual indeed.

Many details of Hart’s life are uncertain, with available reports being varied and often contradictory. It is thoughts that Hart reconciled with and left her husband several times. During their time together they had two children, a boy and a girl, whom Hart sent to her mother who was then living in Ohio. At least her children had a stable home. In 1893, the couple attended the Chicago World’s Fair, where he worked for a time as a midway barker. She in turn developed a fascination with the cowboy lifestyle while watching Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. At the end of the World’s Fair, Hart left her husband again on a train bound for Trinidad, Colorado, possibly in the company of a piano player named Dan Bandman.

By early 1898, Hart was in the town of Mammoth, Arizona. Some reports indicate she was working as a cook in a boardinghouse, while others indicate she was operating a tent brothel near the local mine. While doing well for a time, her financial outlook took a downturn after the mine closed. About this time Hart attested to receiving a message asking her to return home to her seriously ill mother. Looking to raise money, Hart and a friend known only as “Joe Boot” worked an old mining claim he owned, but they found no gold in the claim.

It was then that they decided to rob the stagecoach traveling between Globe and Florence, Arizona. On May 30, 1899, at a watering point near Cane Springs Canyon, about 30 miles southeast of Globe, they began their robbery run. Hart had cut her hair short and dressed in men’s clothing. Hart was armed with a .38 revolver while Boot had a Colt .45 revolver. The stagecoach run had not been robbed in several years, so the coach did not have a shotgun messenger. The pair stopped the coach and Boot held a gun on the robbery victims while Hart took $431.20, which would be about $13,500 today, and two firearms from the passengers. After returning $1 to each passenger, she then took the driver’s revolver. It was such an odd gesture. After the robbers made their getaway, the driver unhitched one of the horses, headed to town to alert the sheriff.

Accounts of the next few days vary. According to Hart, the pair took a circuitous route designed to lose anyone who followed while they made their future plans. Others claim the pair became lost and wandered in circles. Regardless, a posse led by Sheriff Truman of Pinal County caught up with the pair on June 5, 1899. Finding both of them asleep, Sheriff Truman reported that Boot surrendered quietly while Hart fought to avoid capture. Hart was eventually caught and after being found guilty, sentenced to five years in prison. She was pardoned

after three years. Some accounts have her returning to Tucson 25 years after her imprisonment to visit the jail cell that once held her. A census taker in 1940 claimed to have discovered Hart living in Arizona under a different name, as she had married again. Pearl Bywater was living a private life with her husband of 50 years, George Calvin “Cal” Bywater. She is acknowledged as the only known female stagecoach robber in Arizona’s history, earning her the nicknames of “Bandit Queen” or “Lady Bandit.”

after three years. Some accounts have her returning to Tucson 25 years after her imprisonment to visit the jail cell that once held her. A census taker in 1940 claimed to have discovered Hart living in Arizona under a different name, as she had married again. Pearl Bywater was living a private life with her husband of 50 years, George Calvin “Cal” Bywater. She is acknowledged as the only known female stagecoach robber in Arizona’s history, earning her the nicknames of “Bandit Queen” or “Lady Bandit.”

Before the helicopter was invented, getting wounded men out of the battlefield was much harder. Transporting the wounded is dangerous work, whether you are driving, walking, or flying them out, but the helicopter could get in and out so much faster than any other mode of transportation, and once they were up, they were often out of range of the guns below. That made their escape much more likely to happen. In December 1961, the USS Core (T-AKV-41) docked in Saigon with 82 US Army Piasecki H-21 helicopters. Operation Chopper commenced a little more than 12 days later.

Before the helicopter was invented, getting wounded men out of the battlefield was much harder. Transporting the wounded is dangerous work, whether you are driving, walking, or flying them out, but the helicopter could get in and out so much faster than any other mode of transportation, and once they were up, they were often out of range of the guns below. That made their escape much more likely to happen. In December 1961, the USS Core (T-AKV-41) docked in Saigon with 82 US Army Piasecki H-21 helicopters. Operation Chopper commenced a little more than 12 days later.

On January 12, 1962, the first helicopter assault, called Operation Chopper, took place when 33 United States Army CH-21C Shawnee transport helicopters of the 8th and 57th Transportation Companies airlifted 1,036 soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) into battle against an insurgent Viet Cong (National Liberation Front) stronghold, approximately 10 miles west of Saigon. The landing zone was 150 yards by 300 yards and surrounded by tall trees. While there were trees surrounding the field, the area was still not very safe. Nevertheless, the VC were surprised and soundly defeated, but they gained valuable combat experience they later used with great effect against American troops.

The paratroopers also captured an underground radio transmitter. This operation heralded a new era of air mobility for the US Army, which had been slowly growing as a concept since the Army formed twelve helicopter battalions in 1952 as a result of the Korean War. These new battalions eventually formed a sort of modern-day cavalry for the Army.

The Piasecki Helicopter Company CH-21C Shawnee was a single-engine, tandem rotor transport helicopter. The flight crew consisted of three men, with the addition of one or two gunners. It could transport up to 20 soldiers  under ideal conditions. The helicopter’s overall length was 86 feet, 4 inches, with its rotors running. It was 15 feet, 9 inches high. The rotors were 44 feet in diameter and the fuselage was 52 feet, 7 inches long. The empty weight was 8,950 pounds and maximum takeoff weight was 15,200 pounds.

under ideal conditions. The helicopter’s overall length was 86 feet, 4 inches, with its rotors running. It was 15 feet, 9 inches high. The rotors were 44 feet in diameter and the fuselage was 52 feet, 7 inches long. The empty weight was 8,950 pounds and maximum takeoff weight was 15,200 pounds.

The Piasecki Helicopter was not without its issues, however. Its performance in the hot and humid climate of Southeast Asia was limited, restricting the troop load to 9 soldiers, out of the 20-person capacity the helicopter was said to have. It was withdrawn from service in 1964 when the Bell HU-1A Iroquois began to replace it. All CH-21Cs were retired when the CH-47 Chinook assumed its role in 1965.

Hallucinations are not an uncommon phenomenon after long periods of time at sea, but on January 9, 1493, explorer Christopher Columbus, sailing near the Dominican Republic, saw something in the water that was not a hallucination, rather just something he had never seen before. Columbus knew the sea. He was a sailor, but this was not something he had seen before, and he had no knowledge of such a creature to draw from.

Hallucinations are not an uncommon phenomenon after long periods of time at sea, but on January 9, 1493, explorer Christopher Columbus, sailing near the Dominican Republic, saw something in the water that was not a hallucination, rather just something he had never seen before. Columbus knew the sea. He was a sailor, but this was not something he had seen before, and he had no knowledge of such a creature to draw from.

Well, it seems like if we don’t have any idea of what something is, we tend to draw from fiction. That was what Colombus did when he mistakenly thought these creatures in the water were three mermaids. Well, of course, they weren’t mermaids, but manatees. Columbus was so sure of what he saw that he even described them in his journals as “not half as beautiful as they are painted.” Well, if you have seen a manatee, you will agree that they really aren’t what we would call “beautiful.”

Columbus had been at sea for six months, setting sail from Spain, heading across the Atlantic Ocean with the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria, hoping to find a western trade route to Asia. Of course, we now know that his voyage, the first of four he would make, led him to the Americas, or “New World.” Maybe, it was his long months at sea that caused him to imagine mermaids. Or maybe seeing only water for so long and so far, made the manatees look different to him than they really did, although, he did not imagine them to be beautiful.

Mermaids are, of course, mythical half-female, half-fish creatures, that have graced the imaginations of seafaring cultures since the time of the ancient Greeks. “Typically depicted as having a woman’s head and torso, a fishtail instead of legs and holding a mirror and comb, mermaids live in the ocean and, according to some legends, can take on a human shape and marry mortal men. Mermaids are closely linked to sirens, another folkloric figure, part-woman, part-bird, who live on islands and sing seductive songs to lure sailors to their deaths.”

Those Mermaid sightings by sailors were most likely manatees, dugongs, or Steller’s sea cows…which became extinct by the 1760s due to over-hunting. Manatees are slow-moving aquatic mammals with human-like eyes, bulbous faces and paddle-like tails. There are three different species of manatee…West Indian, West African and Amazonian, and one species of dugong which belong to the Sirenia order. As adults, Manatee are typically

10 to 12 feet long and weigh 800 to 1,200 pounds…not exactly the sleek lines most people would associate with the feminine beauty of the mermaid. Manatees are plant-eaters, have a slow metabolism, and can only survive in warm water. Manatees live an average of 50 to 60 years in the wild and have no natural predators. However, they are an endangered species. In the United States, the majority of manatees are found in Florida, where scores of them die or are injured each year due to collisions with boats.

10 to 12 feet long and weigh 800 to 1,200 pounds…not exactly the sleek lines most people would associate with the feminine beauty of the mermaid. Manatees are plant-eaters, have a slow metabolism, and can only survive in warm water. Manatees live an average of 50 to 60 years in the wild and have no natural predators. However, they are an endangered species. In the United States, the majority of manatees are found in Florida, where scores of them die or are injured each year due to collisions with boats.

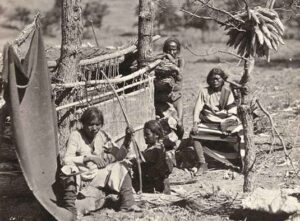

When the White Man came to this country, little was known about how the Indians lived or the things they used to make their lives easier. These days, we have learned much about all that. Things like killing the buffalo and using pretty much every part of the animal for things like food, clothing, weapons, and probably much more. They were also artists, to a degree that we can only imagine. They drew things and made things…from next to nothing…and as we know now, they were very good artists, especially with weaving. Once the Indians found out how much the white colonists liked their weaving, they began to make blankets and rugs to trade for other goods. Before then, the weaving was only used to make clothing for the tribe.

When the White Man came to this country, little was known about how the Indians lived or the things they used to make their lives easier. These days, we have learned much about all that. Things like killing the buffalo and using pretty much every part of the animal for things like food, clothing, weapons, and probably much more. They were also artists, to a degree that we can only imagine. They drew things and made things…from next to nothing…and as we know now, they were very good artists, especially with weaving. Once the Indians found out how much the white colonists liked their weaving, they began to make blankets and rugs to trade for other goods. Before then, the weaving was only used to make clothing for the tribe.

The Navajo people learned the how to build looms and weave fabrics from the Hopi Indians. This new “business venture” brought about a sedentary life as they spent long hours sitting and weaving. They soon learned to make beautiful blankets with geometric shapes, diamonds, and zig-zag patterns. Navajo rugs and blankets are almost exclusively produced by Navajo people of the Four Corners area of the United States. They have been highly sought after, for their beautiful craftsmanship for over 150 years.

The weavings of the Navajo people soon became a commercial production in the Four Corners area. I have

been there and seen them myself. It was very interesting. These days, it is all a part of the tourism industries. As one expert expresses it, “Classic Navajo serapes at their finest equal the delicacy and sophistication of any pre-mechanical loom-woven textile in the world.” Some old-world crafts really can’t be improved upon by using modern-day equipment. The old ways are simply the best ways, sometimes.

been there and seen them myself. It was very interesting. These days, it is all a part of the tourism industries. As one expert expresses it, “Classic Navajo serapes at their finest equal the delicacy and sophistication of any pre-mechanical loom-woven textile in the world.” Some old-world crafts really can’t be improved upon by using modern-day equipment. The old ways are simply the best ways, sometimes.

What makes a Medal of Honor winner? I don’t mean what act actually earns them the medal, but rather what causes them to get to that point and beyond. The Medal of Honor is the United States government’s highest and most prestigious military decoration that may be awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, Space Force guardians, and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor…or great courage in the face of danger, especially in battle. I seriously doubt if the winner gave any thought to what he had to do to win the medal…there is just no time, and people don’t perform heroic acts just for the medal. It’s bigger than that.

What makes a Medal of Honor winner? I don’t mean what act actually earns them the medal, but rather what causes them to get to that point and beyond. The Medal of Honor is the United States government’s highest and most prestigious military decoration that may be awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, Space Force guardians, and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor…or great courage in the face of danger, especially in battle. I seriously doubt if the winner gave any thought to what he had to do to win the medal…there is just no time, and people don’t perform heroic acts just for the medal. It’s bigger than that.

One man, Corporal Ronald Rosser, earned his Medal of Honor while serving in the 38th Regiment of the 2nd Infantry Division during the Korean War. Rosser enlisted in Army at the age of 17 and served from 1946 until 1949. His tour was finished, and he went home, but then his younger brother was killed in Korea in February of 1951. Rosser was devastated, but instead of wallowing in grief, he chose to honor his brother. Rosser re-enlisted to “finish his [brother’s] tour” of duty. Revenge was the only thing he could do for his brother now, and Rosser wanted revenge. In January of 1952, Rosser was a part of the regiment’s L Company. L Company was dispatched to capture an enemy-occupied hill. The battle there was fierce and enemy resistance caused heavy casualties. L Company was reduced to just 35 men from the initial 170 sent out, but they were ordered to make one more  attempt to take the hill. Orders are orders, and as I said, the men didn’t really have time to think about how they could prove their courage. Rosser rallied the remaining men and charged the hill. Enemy fire continued to be heavy, but Rosser attacked the enemy position three times, killing 13 enemy soldiers, and although wounded himself, carried several men to safety. It truly was a courageous act, and one worthy of the Medal of Honor, but not one that Rosser had planned in any way. He just knew that he needed to save as many lives as he could, because he couldn’t live with himself if he didn’t. On June 27, 1952, Rosser was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman at the White House for his heroism. On September 20, 1966, another of Rosser’s brothers, PFC Gary Edward Rosser, USMC, was killed in action, this time in the Vietnam War. Rosser requested a combat assignment in Vietnam but was rejected and subsequently retired from the army soon after. Rosser married Sandra Kay (nee Smith) Rosser who died November 28, 2014. He was the father of Pamela (nee Rosser) Lovell. Rosser died on August 26, 2020, in Bumpus Mills, Tennessee at the age of 90.

attempt to take the hill. Orders are orders, and as I said, the men didn’t really have time to think about how they could prove their courage. Rosser rallied the remaining men and charged the hill. Enemy fire continued to be heavy, but Rosser attacked the enemy position three times, killing 13 enemy soldiers, and although wounded himself, carried several men to safety. It truly was a courageous act, and one worthy of the Medal of Honor, but not one that Rosser had planned in any way. He just knew that he needed to save as many lives as he could, because he couldn’t live with himself if he didn’t. On June 27, 1952, Rosser was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman at the White House for his heroism. On September 20, 1966, another of Rosser’s brothers, PFC Gary Edward Rosser, USMC, was killed in action, this time in the Vietnam War. Rosser requested a combat assignment in Vietnam but was rejected and subsequently retired from the army soon after. Rosser married Sandra Kay (nee Smith) Rosser who died November 28, 2014. He was the father of Pamela (nee Rosser) Lovell. Rosser died on August 26, 2020, in Bumpus Mills, Tennessee at the age of 90.

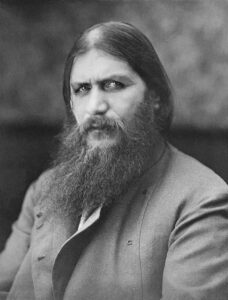

Czar Nicholas II and Czarina Alexandra were not always considered popular, in fact you could say that the tumultuous reign of Nicholas II, who was the last czar of Russia, was tarnished by his ineptitude in both foreign and domestic affairs that helped to bring about the Russian Revolution. Nevertheless, he was a part of the Romanov Dynasty, which had ruled Russia for three centuries.

Czar Nicholas II and Czarina Alexandra were not always considered popular, in fact you could say that the tumultuous reign of Nicholas II, who was the last czar of Russia, was tarnished by his ineptitude in both foreign and domestic affairs that helped to bring about the Russian Revolution. Nevertheless, he was a part of the Romanov Dynasty, which had ruled Russia for three centuries.

I think that his young son, Alexi’s health issues played a rather large part in what many would consider his failure to lead, but things were looking up for the family when a young Siberian-born muzhik, or peasant, who underwent a religious conversion as a teenager and proclaimed himself a healer with the ability to predict the future, won the favor of Czar Nicholas II and Czarina Alexandra. Grigory Efimovich Rasputin was able, through his ability, to stop the bleeding of their hemophiliac son, Alexei, in 1908.

Many people, from that time forward, began to criticize Rasputin for his lechery and drunkenness, if these things are true. The left-wing Bolsheviks were deeply unhappy with the government and began spreading calls for a military uprising. The Bolsheviks were a revolutionary party, dedicated to Karl Marx’s ideas, and they wanted a coup d’etat, which is a sudden, violent, and unlawful seizure of power from a government. That said, the last thing they needed was a “miracle-working holy man” advising the Czar. Rasputin exerted a powerful influence on the ruling family of Russia, infuriating nobles, church orthodoxy, and peasants alike. He particularly influenced the czarina and was rumored to be her lover.

Rasputin had to go, so sometime over the course of the night and the early morning of December 29-30, 1916, Grigory Efimovich Rasputin was murdered by Russian nobles eager to end his influence over the royal family.  Still, that wasn’t all, and the rest of it should have scared them…to death. A group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Youssupov, the husband of the czar’s niece, and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Nicholas’s first cousin, lured Rasputin to Youssupov Palace on the night of December 29, 1916. First, Rasputin’s would-be killers first gave the monk food and wine laced with cyanide…which miraculously had no effect on him. When he failed to react to the poison, they shot him at close range, leaving him for dead. Once again, they failed to kill him. Rasputin revived a short time later and attempted to escape from the palace grounds. They caught up with him and shot him again, and then beat him viciously. Finally, because Rasputin was still alive, they bound him and tossed him into a freezing river. His body was discovered several days later and the two main conspirators, Youssupov and Pavlovich were exiled. It was the beginning of the end. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 put an end to the imperial regime. Nicholas and Alexandra were murdered, and the long, dark reign of the Romanovs was over.

Still, that wasn’t all, and the rest of it should have scared them…to death. A group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Youssupov, the husband of the czar’s niece, and Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Nicholas’s first cousin, lured Rasputin to Youssupov Palace on the night of December 29, 1916. First, Rasputin’s would-be killers first gave the monk food and wine laced with cyanide…which miraculously had no effect on him. When he failed to react to the poison, they shot him at close range, leaving him for dead. Once again, they failed to kill him. Rasputin revived a short time later and attempted to escape from the palace grounds. They caught up with him and shot him again, and then beat him viciously. Finally, because Rasputin was still alive, they bound him and tossed him into a freezing river. His body was discovered several days later and the two main conspirators, Youssupov and Pavlovich were exiled. It was the beginning of the end. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 put an end to the imperial regime. Nicholas and Alexandra were murdered, and the long, dark reign of the Romanovs was over.