History

Whenever a ship sinks, it takes with it a lot of gear, personal effects, and sometimes treasures. These days, they send in the submarines, or rather the mini submarines to salvage whatever they can, find out what caused the sinking, and sometimes to aid in raising the ship to the surface. In times past, when a ship went down, it could easily be lost forever, or at least until more modern times when they could finally find it again.

Whenever a ship sinks, it takes with it a lot of gear, personal effects, and sometimes treasures. These days, they send in the submarines, or rather the mini submarines to salvage whatever they can, find out what caused the sinking, and sometimes to aid in raising the ship to the surface. In times past, when a ship went down, it could easily be lost forever, or at least until more modern times when they could finally find it again.

When the Vasa, an amazingly beautiful Swedish warship that sank on its maiden voyage, 1400 yards into its voyage sat in the harbor for years. The did manage to get the cannon from it right away, but everything else sat underwater until the 1950s, when they had a better way to salvage it. When the world’s first completely covered underwater diving suit was invented around 1715, it consisted of an airtight oak barrel. The suit was used mainly for salvage operations of shipwrecks. I wonder what they could have done with Vasa using that. Vasa wasn’t in dangerously deep water, and could have been accessed easily today, but they just didn’t have the equipment.

The cross between a diving bell and standard diving dress is rather interesting. I wonder if the barrel design John Lethbridge used in 1715 was seriously difficult to move in. It reminds me a of a comical space suit, but I guess it served its purpose. However odd it is, it was the first underwater diving suit, and it is currently located in the Cité de la Mer, a maritime museum in Cherbourg, France.

Lethbridge came up with the idea for his diving suit while working for the East India Company as a salvager. The barrel was airtight, so the diver was protected and safe. The barrel was six feet in length, and the diver had little control of it once it was lowered into the water. The diver had to lay flat on his stomach once the barrel. The barrel had two airtight holes on the sides for the diver’s hands and a hole with glass in the front for use as the diver’s viewing window. During trials, Lethbridge demonstrated that the suit enabled divers to stay 12 fathoms (a unit of length equal to six feet) underwater for at least 30 minutes at a time. That was hard for  me to figure out, until I read that once the diver comes out of the water after 30 minutes, the crew pumped fresh air into the suit through a vent using bellows. At the same time, the used air was let out through another vent. Then, with the fact that the barrel was airtight, the diver was good for another 30 minutes. It wasn’t perfect, but it was much further along than salvage operations had been before it. The suit, while odd and very primitive was an immediate success. It was used mostly to retrieve material from shipwrecks. During Lethbridge’s first salvage…the maiden voyage of the diving suit, as it were, Lethbridge recovered 25 chests of silver and 65 cannons! I would call that a definite success.

me to figure out, until I read that once the diver comes out of the water after 30 minutes, the crew pumped fresh air into the suit through a vent using bellows. At the same time, the used air was let out through another vent. Then, with the fact that the barrel was airtight, the diver was good for another 30 minutes. It wasn’t perfect, but it was much further along than salvage operations had been before it. The suit, while odd and very primitive was an immediate success. It was used mostly to retrieve material from shipwrecks. During Lethbridge’s first salvage…the maiden voyage of the diving suit, as it were, Lethbridge recovered 25 chests of silver and 65 cannons! I would call that a definite success.

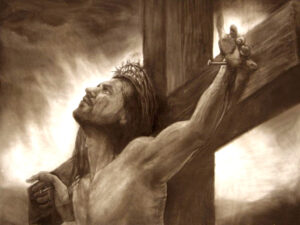

In a time of world chaos, one thing stands out…Jesus. We all need Jesus. It’s hard to believe that a sinless man would be willing to carry the sins of the world. None of us could or would do that. We would most likely fear death too much…at least at such a young age. It is believed that Jesus was about 33 years old. Most of us would feel like we had too much to live for at that age, and yet, Jesus endured the scourging, the “trial” that was nothing more than a lynch mob, and the horrible suffocating death on the cross, because He saw joy set before Him…JOY, how could that be? How could Jesus see the torture and death that was coming to Him as joy, because mankind could still come to Heaven…that was His joy.

In a time of world chaos, one thing stands out…Jesus. We all need Jesus. It’s hard to believe that a sinless man would be willing to carry the sins of the world. None of us could or would do that. We would most likely fear death too much…at least at such a young age. It is believed that Jesus was about 33 years old. Most of us would feel like we had too much to live for at that age, and yet, Jesus endured the scourging, the “trial” that was nothing more than a lynch mob, and the horrible suffocating death on the cross, because He saw joy set before Him…JOY, how could that be? How could Jesus see the torture and death that was coming to Him as joy, because mankind could still come to Heaven…that was His joy.

He saw the joy of a world that could be back in right standing with God. Something we could never have achieved on our own. This world was in a seriously horrible place…even more so than the chaos we are in right now. The wages of sin is death, and we had all sinned. It was going to take the death of a man to pay for the sins of the world, but that man had to be sin-free. In the beginning, a sinless man sinned, thereby giving away his birthright of eternal life. So that meant either all mankind had to die and go to Hell, or a sinless man had to die to pay the price for all of us. Enter Jesus, and thank God He was willing to pay that price for us.

That was what Jesus did for us when He went to the cross on Good Friday. I don’t know if many of you really know what scourging is, but let me tell you. The Romans were famous for their horrific types of torture. The “whip” they used to beat (scourge) Jesus usually had nails or pieces of metal or glass attached to them. The purpose of these things being attached to the whips tails was to rip the flesh off of the victim. By the time they were done, internal organs were often visible. Then they took Jesus, after making Him carry His own cross, and nailed Him to that cross. The way they nailed Him to the cross meant that He had to push up with His feet to be able to get air into His lungs. The more tired the victim became, the less they would be able to raise themselves up so they could breathe. It was a matter of slow suffocation. That was what Jesus endured to give us the opportunity to have eternal life again. Nevertheless, it was and is still our choice. I just can’t imagine how anyone could choose not to receive that totally free gift of God. I know I will not refuse that gift.

After being in the grave for three days, Jesus arose from the dead triumphant with the victory, and the keys to the kingdom, which He gave back to us. We can have it all…because He lives. He is risen!! He is alive!! And because Jesus lives, I can face tomorrow, no matter how ugly this world looks today. Victory is mine!! Heaven belongs to me!! I am free, because Jesus paid the price for me…and for you too…should you choose to receive. Praise God…Jesus is risen!! Happy Resurrection Day everyone!!

After being in the grave for three days, Jesus arose from the dead triumphant with the victory, and the keys to the kingdom, which He gave back to us. We can have it all…because He lives. He is risen!! He is alive!! And because Jesus lives, I can face tomorrow, no matter how ugly this world looks today. Victory is mine!! Heaven belongs to me!! I am free, because Jesus paid the price for me…and for you too…should you choose to receive. Praise God…Jesus is risen!! Happy Resurrection Day everyone!!

There are all kinds of records, but some are just stranger than others. Switzerland actually holds a strange record…for attacking its neighbor, Liechtenstein. This is particularly odd in that Switzerland is a neutral nation…very opposed to war!! In fact, Switzerland is the longest standing neutral nation in the world and has not taken part in a “war” since 1505. Its official stance of non-involvement had been decided during The Congress of Vienna in 1815, in which major European leaders met to discuss the nature of Europe after the defeat of Napoleon. Nevertheless, they do have an army.

There are all kinds of records, but some are just stranger than others. Switzerland actually holds a strange record…for attacking its neighbor, Liechtenstein. This is particularly odd in that Switzerland is a neutral nation…very opposed to war!! In fact, Switzerland is the longest standing neutral nation in the world and has not taken part in a “war” since 1505. Its official stance of non-involvement had been decided during The Congress of Vienna in 1815, in which major European leaders met to discuss the nature of Europe after the defeat of Napoleon. Nevertheless, they do have an army.

Diplomatic and economic relations between Switzerland and Liechtenstein have been good. In fact, you could say relations were very good, with Switzerland accepting the role of safeguarding the interests of its tiny next-door neighbor. Liechtenstein has an embassy in Bern, Switzerland, and Switzerland is accredited to Liechtenstein from its Federal Department of Foreign Affairs in Bern and maintains an honorary consulate in Vaduz, Liechtenstein. The two countries also share an open border, mostly along the Rhine, but also in the Rätikon range of the Alps, between the Fläscherberg and the Naafkopf.

With all that “good will” between the nations, you would never expect conflict, but apparently, Switzerland has  attacked Liechtenstein three times in 30 years. Of course, it was by mistake each time! How does that happen? Nevertheless, it did. The first time was probably the only “aggressive” accident of the bunch. On December 5, 1985, during an artillery exercise, the Swiss Army had launched munitions in the middle a winter storm. The wind took the munitions way off course, into the Bannwald Forest of Liechtenstein, and started a forest fire. No one was injured and the Liechtenstein government was very angry. Switzerland had to pay a heavy penalty for the environmental damage caused. The second attack took place on October 13, 1992. The Swiss Army received orders to set up an observation post in Treisenberg. They followed the orders and marched to Treisenberg. What they didn’t realize was that Treisenberg lies within the territory of Liechtenstein. They marched into Treisenberg with rifles and only later realized that they were in Liechtenstein. The last attack was on March 1, 2007. A group of Swiss Army infantry soldiers was in training when the weather took a bad turn. There was heavy rainfall, and the soldiers were not carrying any GPS or compass. Eventually, they ended up in Liechtenstein! Switzerland apologized to the Liechtenstein government for the intrusion, yet again.

attacked Liechtenstein three times in 30 years. Of course, it was by mistake each time! How does that happen? Nevertheless, it did. The first time was probably the only “aggressive” accident of the bunch. On December 5, 1985, during an artillery exercise, the Swiss Army had launched munitions in the middle a winter storm. The wind took the munitions way off course, into the Bannwald Forest of Liechtenstein, and started a forest fire. No one was injured and the Liechtenstein government was very angry. Switzerland had to pay a heavy penalty for the environmental damage caused. The second attack took place on October 13, 1992. The Swiss Army received orders to set up an observation post in Treisenberg. They followed the orders and marched to Treisenberg. What they didn’t realize was that Treisenberg lies within the territory of Liechtenstein. They marched into Treisenberg with rifles and only later realized that they were in Liechtenstein. The last attack was on March 1, 2007. A group of Swiss Army infantry soldiers was in training when the weather took a bad turn. There was heavy rainfall, and the soldiers were not carrying any GPS or compass. Eventually, they ended up in Liechtenstein! Switzerland apologized to the Liechtenstein government for the intrusion, yet again.

Thankfully these “accidental” attacks were not of a deadly nature. They were really more a “comedy of errors” than an attack. Thankfully, the people of Liechtenstein saw the “attacks” for what they were, and tended to care for their “intruders,” rather than fight back. Of course, that would have been difficult too, since Liechtenstein does not have an army of their own, and so depended on the “protection” of their neighbors…when they didn’t accidentally attack them.

The Olympics…the dream of every serious athlete. While most of us will never get there, but many of us love to watch the best of the best athletes vie for the world title of Olympic Gold. These athletes would do just about anything to win. The men’s marathon in the 1904 Olympic Games was no exception.

The Olympics…the dream of every serious athlete. While most of us will never get there, but many of us love to watch the best of the best athletes vie for the world title of Olympic Gold. These athletes would do just about anything to win. The men’s marathon in the 1904 Olympic Games was no exception.

This race might have been the strangest race in history…going forward or backward. Only a few of the runners had any experience in running a race…much less a marathon, and the others were…well, “oddities” to say the least. That marathon was more of a comedy show than a serious race. The runners consisted of ten Greeks who had never run a marathon. Two of these belonged to the Tsuana tribe of South Africa and arrived barefoot to the race, and one competitor was a Cuban mailman who wore street clothing to the race. These days, they would almost be laughed off the track. I can just hear the shocked voices throughout the crowd at that race.

If you thought the apparel was odd…well hold on to your horses, because the “level of strange” is just getting started. The first to complete the race was American runner named Fred Lorz. Apparently, Lorz had dropped out of the race after nine miles and then hitch-hiked in a car. When the car broke down at the 19th mile, he jogged to the finish line. He was disqualified and banned from the competition for life. Sounds fair to me. The second to arrive, and the champion with Lorz disqualification, was Thomas Hicks. Ten miles from the finish line, he had almost given up, but his trainers urged him to continue. Still, it was an enormous struggle. He was given several doses of strychnine, a common rat poison, to help get him to the end of the race…WHAT!! When he reached the stadium, his trainers and supporters carried him to the finish line! It’s a wonder their “energy  boost” didn’t kill him!! Even though he got the gold medal that time, he never ran professionally again. A Cuban postman named Andarín Carvajal, ran the race in street clothes. To top it off, he had not eaten in 40 hours. Before a race!! Are you kidding me!! He got hungry and took a detour into an apple orchard during the race. He ate some rotten apples that gave him stomach cramps. Despite falling ill, he managed to finish in the fourth place!! Where were all the other racers, while he was taking his dinner break? If you ask me, this had to be the strangest marathon ever. It was almost like they were making it up as they went along.

boost” didn’t kill him!! Even though he got the gold medal that time, he never ran professionally again. A Cuban postman named Andarín Carvajal, ran the race in street clothes. To top it off, he had not eaten in 40 hours. Before a race!! Are you kidding me!! He got hungry and took a detour into an apple orchard during the race. He ate some rotten apples that gave him stomach cramps. Despite falling ill, he managed to finish in the fourth place!! Where were all the other racers, while he was taking his dinner break? If you ask me, this had to be the strangest marathon ever. It was almost like they were making it up as they went along.

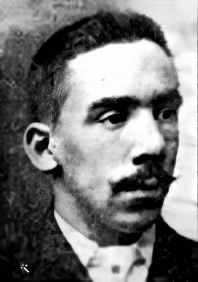

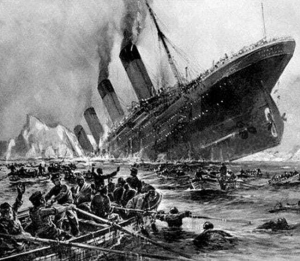

Charles Joughin had to figure that he was one of the most fortunate people on earth in 1912. Joughin was a British-American chef who had just landed a job as the chief baker on the greatest ship there was at the time…Titanic. Charles Joughin was born on Patten Street, next to the West Float in Birkenhead, England, on August 3, 1878. His parents were John Edwin (1846–1886)…a licensed victualer (a British person who is licensed to sell alcoholic liquor), and Ellen (Crombleholme) Joughin (1850–1938). He was enamored with the sea his whole young life, and he first went to sea in 1889 at age 11. He went on to become chief baker on various White Star Line steamships, notably the RMS Olympic, Titanic’s sister ship.

Charles Joughin had to figure that he was one of the most fortunate people on earth in 1912. Joughin was a British-American chef who had just landed a job as the chief baker on the greatest ship there was at the time…Titanic. Charles Joughin was born on Patten Street, next to the West Float in Birkenhead, England, on August 3, 1878. His parents were John Edwin (1846–1886)…a licensed victualer (a British person who is licensed to sell alcoholic liquor), and Ellen (Crombleholme) Joughin (1850–1938). He was enamored with the sea his whole young life, and he first went to sea in 1889 at age 11. He went on to become chief baker on various White Star Line steamships, notably the RMS Olympic, Titanic’s sister ship.

Joughin married Louise Woodward (born 11 July 1879), a native of Douglas, Isle of Man, on November 17, 1906, in Liverpool, England. They had a daughter, Agnes Lillian, in 1907, and a son, Roland Ernest, in 1909. It is believed that Louise died from complications in childbirth around 1919. Their new son, Richard, was also lost. It was a low point in his life.

As we all know, the job Joughin landed on the Titanic was going to prove to be a disaster. When the ship hit an iceberg on the evening of April 14th, at 11:40pm, Joughin was off duty. He was in his bunk when he felt the shock of the collision and immediately got up. He knew that this could not be good. Word was being passed down from the upper decks that officers were getting the lifeboats ready for launching. Joughin sent his thirteen men up to the boat deck with provisions for the lifeboats…four loaves of bread apiece, about forty pounds of bread. Joughin stayed behind for a time, but then followed them, reaching the Boat Deck at around 12:30am, he then helped with the evacuation.

Once on deck, Joughin joined Chief Officer Henry Tingle Wilde by Lifeboat 10. Joughin and the stewards and other seamen began helping the ladies and children through the crowd of people to the lifeboat. Sadly, many of the women were more afraid of the lifeboats than they were the sinking Titanic. They began to run away, saying that they were safer aboard the Titanic than in the tiny boats being tossed in the waves. Leaving him no choice, the Chief Baker then went on to A Deck and forcibly brought up women and children, throwing them into the lifeboat.

Joughin had been assigned as captain of Lifeboat 10, but he did not board the boat, because it was already being crewed by two sailors and a steward. After Lifeboat 10 was launched, Joughin went below, and “had a drop of liqueur” in his quarters, which was in reality a tumbler half-full of whiskey, as he later specified. Joughin was sure that he would not be one of the people allowed onboard a lifeboat, because there were simply not enough lifeboats to hold all the people onboard Titanic. After his drink, Joughin came upstairs again, after meeting “the old doctor,” assumedly William O’Loughlin. This was quite possibly the last time anyone ever saw  O’Loughlin. When Joughin arrived back at the Boat Deck, the rushing for boats had ended, because all the boats had been lowered. He then went down into the A Deck promenade and threw about fifty deck chairs overboard so that they could be used as flotation devices, by the unfortunate ones who could not get into a boat.

O’Loughlin. When Joughin arrived back at the Boat Deck, the rushing for boats had ended, because all the boats had been lowered. He then went down into the A Deck promenade and threw about fifty deck chairs overboard so that they could be used as flotation devices, by the unfortunate ones who could not get into a boat.

Joughin then went into the deck pantry on A Deck, for a drink of water. Suddenly, he heard a loud crash, “as if part of the ship had buckled” and indeed it had. He left the pantry and joined the crowd running aft toward the poop deck. As he was crossing the well deck, the ship suddenly gave a list over to port and, according to him, threw everyone in the well in a pile except for him. Joughin climbed to the starboard side of the poop deck, and hoisted himself over the safety rail, so that he was on the outside of the ship as it went down by the head. As the ship went down in a vertical position at 2:20am on April 15, 1912, Joughin rode it down as if it were an elevator, somehow managing not to get his head under the water. He said his head “may have been wetted, but no more.” So it was that Joughin was the last survivor to leave the Titanic. Now began his real ordeal.

Joughin testified that he kept paddling and treading water for about two hours. He also admitted to hardly feeling the cold, which he credited to the whiskey he drank. When daylight broke, he spotted the upturned Collapsible B lifeboat, with Second Officer Charles Lightoller and around 30 men standing on the side of the boat. Joughin slowly swam towards it, but there was no room for him. Cook Isaac Maynard, recognized him and held his hand as the Chief Baker held onto the side of the boat, with his feet and legs still in the water. A short time later, another lifeboat appeared and Joughin swam to it. He was taken in, where he stayed until he boarded the RMS Carpathia that had come to their rescue. Miraculously, he was rescued from the sea with only swollen feet. He survived the ship’s sinking, becoming notable for having survived in the frigid water for an exceptionally long time before being pulled onto the overturned Collapsible B lifeboat with virtually no ill effects. It is estimated that he was in the water for about four hours.

After surviving the Titanic disaster, Joughin returned to England, and was one of the crew members who reported to testify at the British Wreck Commissioner’s inquiry into the sinking headed by Lord Mersey. In 1920, Joughin moved permanently to the United States to Paterson, New Jersey. According to his obituary he was also on board the SS Oregon when it sank in Boston Harbor in 1886. He also served on American Export  Lines ships and on World War II troop transports before retiring in 1944.

Lines ships and on World War II troop transports before retiring in 1944.

After moving to New Jersey, he remarried to Mrs Annie Eleanor (Ripley) Howarth Coll (born December 29, 1870), a native of Leeds, who had first come to the USA in 1888. Annie was twice widowed twice and had a daughter named Rose, who was born in 1891. Annie’s death in 1943 was a great loss from which he never recovered. Twelve years later, Joughin was invited to describe his experiences in a chapter of Walter Lord’s book, A Night to Remember. Soon afterwards, his health rapidly declined. He died in a Paterson hospital on December 9, 1956, at the age of 78, after battling pneumonia for two weeks. He was buried by his wife in the Cedar Lawn Cemetery, in Paterson, New Jersey.

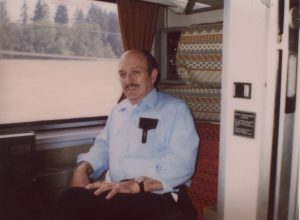

These days, people can buy a ticket to ride a train and have a private room with a bed and bathroom in it to make their trip more comfortable. Since I have taken a train trip from Seattle, Washington to Chicago, Illinois, I can tell you that paying the extra money for that private cabin is really a good idea. We traveled in in a seat among the other passengers, and while the seat was pretty comfortable, it was not comfortable to sleep in. My parents traveled on the Amtrack too, and they did get a private cabin, so their experience was probably much better than mine, although I loved the trip…just not the sleeping part of it. Of course, even with the comfort my parents had on

These days, people can buy a ticket to ride a train and have a private room with a bed and bathroom in it to make their trip more comfortable. Since I have taken a train trip from Seattle, Washington to Chicago, Illinois, I can tell you that paying the extra money for that private cabin is really a good idea. We traveled in in a seat among the other passengers, and while the seat was pretty comfortable, it was not comfortable to sleep in. My parents traveled on the Amtrack too, and they did get a private cabin, so their experience was probably much better than mine, although I loved the trip…just not the sleeping part of it. Of course, even with the comfort my parents had on  their trip, it was nothing compared to the Gilded Age, when the very rich had their own car on the train.

their trip, it was nothing compared to the Gilded Age, when the very rich had their own car on the train.

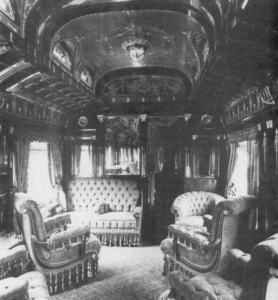

The Gilded Age was a time when the very rich went to great lengths to let all of the “less fortunate ones” know that they had wealth. The Gilded Age took place mostly from 1887 to 1900, with some earlier exceptions. One of the main objectives of life during the Gilded Age, if one could afford it, was to see and be seen in the most luxurious ways possible, and the railway was no different. Commercial air travel didn’t exist then, and cars were very slow. So, when the nation came into the age of the rails, the wealthy made sure that extreme luxury there was no exception. By the 1870s, private railroad cars…some extravagantly decorated…were the most fashionable way to travel. I suppose it would have been like the very

rich on ships, but they could stay a little closer to home, and still travel. The people would never travel in humble wooden coach seats, which I can understand, but most people had no other choice. Money bought comfort.

rich on ships, but they could stay a little closer to home, and still travel. The people would never travel in humble wooden coach seats, which I can understand, but most people had no other choice. Money bought comfort.

With great fanfare, the very rich boarded their own entire rail cars, where the walls were lined in velvet, the upholstery plush, and the decor much like that of a fancy parlor at home. The private cars had bedrooms, running water, and a private water closet. Now expense was spared to make sure that the wealthy car owner was never out of the lap of luxury. It seems like a cruel way to act, but I suppose it is simply the way it is.

World War II was coming to a close and everyone was just doing whatever they could to stay alive. Staff Sergeant Henry E “Red” Erwin Sr was the radio operator on a B-29 Superfortress bomber, piloted by Captain George A “Tony” Simeral. Formed at Dalhart, Texas, in June 1944, and deployed overseas in January 1945, this was a seasoned crew. Erwin’s unit was the 52nd Bombardment Squadron, 29th Bombardment Wing, and Erwin’s B-29 was one of the few planes in Major General Curtis E LeMay’s XXI Bomber Command to have two names. The B-29, serial number 42-65302, was called Snatch Blatch and The City of Los Angeles. On April 12, 1945, the crew was on a bombing mission over Japan. They were part of a campaign to bomb Tokyo and other major Japanese cities.

World War II was coming to a close and everyone was just doing whatever they could to stay alive. Staff Sergeant Henry E “Red” Erwin Sr was the radio operator on a B-29 Superfortress bomber, piloted by Captain George A “Tony” Simeral. Formed at Dalhart, Texas, in June 1944, and deployed overseas in January 1945, this was a seasoned crew. Erwin’s unit was the 52nd Bombardment Squadron, 29th Bombardment Wing, and Erwin’s B-29 was one of the few planes in Major General Curtis E LeMay’s XXI Bomber Command to have two names. The B-29, serial number 42-65302, was called Snatch Blatch and The City of Los Angeles. On April 12, 1945, the crew was on a bombing mission over Japan. They were part of a campaign to bomb Tokyo and other major Japanese cities.

Each of the 12 crew members on the B-29 had additional duties to perform, along with their primary jobs. Erwin’s was to drop phosphorus smoke bombs through a chute in the aircraft’s floor when the lead plane reached a designated assembly area. During the campaign, Erwin pulled the pin and released a bomb into the chute, but the fuse malfunctioned and ignited the phosphorus prematurely, burning at 1,100 degrees. The canister flew back up the chute and into Erwin’s face, blinding him, searing off one ear and obliterating his nose. Phosphorus pentoxide smoke immediately filled the aircraft. It was impossible for the pilot to see his instrument panel. At such a high heat, Erwin was afraid the bomb would burn through the metal floor into the bomb bay. Nevertheless, Erwin had a quick, fleeting chance to save the lives of his fellow crewmembers by risking severe, probably fatal, burns to his own body, and he knew he had to act. He was completely blind, and yet he picked up the flare and feeling his way, crawled around the gun turret and headed for the copilot’s window. His face and arms were covered with ignited phosphorus and his path was blocked by the navigator’s folding table, hinged to the wall but down and locked. By now the navigator was setting up to make a sighting. The table’s latches could not be released with one hand, so Erwin held the white-hot bomb between his bare right arm and  his ribcage. It only took a few seconds to raise the table, but by then, the phosphorus had burned through his flesh to the bone. His body on fire, he stumbled into the cockpit, threw the bomb out the window and collapsed between the pilot’s seats, and with that heroic act, the rest of the crew was saved.

his ribcage. It only took a few seconds to raise the table, but by then, the phosphorus had burned through his flesh to the bone. His body on fire, he stumbled into the cockpit, threw the bomb out the window and collapsed between the pilot’s seats, and with that heroic act, the rest of the crew was saved.

It was the moment of truth for Erwin, who was a modest, humble kind of guy. His thoughts on his heroic actions would have been something along the lines of, “I just did what any soldier would have done…it’s nothing special,” but the truth is, it was something very special and very heroic. Red Erwin came to the war zone as one of thousands of B-29 crewmembers placed in the North Pacific, on the Marianas islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian for the purpose of attacking Japan. The American taxpayer had equipped them with the largest and costliest aircraft of the war, the first large combat plane to be pressurized, enabling the crew to dispense with heated clothing and oxygen masks and to work in shirtsleeves, a fact that also put Erwin in an even more vulnerable position, because his skin was less protected than it would have been in a coat.

Erwin survived his burns. He was flown back to the United States, and after 30 months and 41 surgeries, his eyesight was restored, and he regained use of one arm. He received a disability discharge as a master sergeant in October 1947. In addition to the Medal of Honor and two Air Medals received earlier in 1945, he was also awarded the Purple Heart, the World War II Victory Medal, the American Campaign Medal, three Good Conduct Medals, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two bronze campaign stars (for participation in the Air  Offensive Japan and Western Pacific campaigns), and the Distinguished Unit Citation Emblem. He was a remarkable soldier.

Offensive Japan and Western Pacific campaigns), and the Distinguished Unit Citation Emblem. He was a remarkable soldier.

For 37 years, Erwin served as a benefits counselor at the veterans’ hospital in Birmingham, Alabama. In 1997, the Air Force created the Henry E Erwin Outstanding Enlisted Aircrew Member of the Year Award. It is presented annually to an airman, noncommissioned officer and senior noncommissioned officer in the flight engineering, loadmaster, air surveillance and related career fields. It is only the second Air Force award named for an enlisted person. Henry Erwin, despite his scars and wounds, went on to lead a typical life… marrying, raising children, and becoming a grandfather. But there was nothing “typical” about Red Erwin. “Red” Erwin died at his home on January 16, 2002, and was buried at Elmwood Cemetery in Birmingham, Alabama. His son, Hank Erwin, became an Alabama state senator.

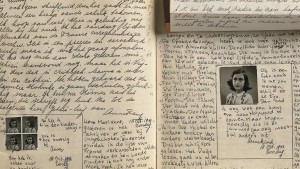

Some books should have a permanent copyright, and it seems like insanity to me that they don’t. As copyright laws go, a work is typically protected for 70 years after the creator’s death. That would mean that a book like Anne Frank’s diary, the copyrights would expire in 2015 because of her untimely death in a concentration camp, and the book would become public domain. It seems very wrong that her diary…her own private words…could become public domain. A diary is so private, but then I guess that when they published her diary, any semblance of privacy no longer existed.

Some books should have a permanent copyright, and it seems like insanity to me that they don’t. As copyright laws go, a work is typically protected for 70 years after the creator’s death. That would mean that a book like Anne Frank’s diary, the copyrights would expire in 2015 because of her untimely death in a concentration camp, and the book would become public domain. It seems very wrong that her diary…her own private words…could become public domain. A diary is so private, but then I guess that when they published her diary, any semblance of privacy no longer existed.

Anne Frank’s diary, the story of which abruptly ended when the family that was secretly hiding them was betrayed, and the two families they were hiding, captured, was preserved after their capture, and given to Otto Frank after he survived the Holocaust. After much soul searching, Otto Frank decided to publish his younger daughter’s story, because people needed to know the truth. It was a selfless move that must have been heartbreaking for a man who had lost everything in the Holocaust…a man whose daughters would never grow to adulthood, never marry, never have children, never grow old. The book became the only way to extend Anne’s life, and through her words to also extend the lives of her mother, sister, and the others who were in hiding. As such, it seems only fitting that the work continue as a copyrighted work beyond 2015, but the law was the law…or was it?

The Swiss foundation, that holds the copyright, made a move to extend the protection of the book. It was a bold, yet simple move. They made Anne’s father, Otto Frank co-author of the book. Of course, a move like this must hold some merit as well. Otto could not be named co-author just because he was her father. While The Diary of Anne Frank was compiled of journal entries made by Anne, it was her father who read through her journal to put together the final product. Otto admitted to having censored some of the content, leaving out

certain parts of her story that he decided were unsavory or too personal. It made sense. After all, this was his daughter, and she was becoming a woman, with the curiosities of that transition. His work in editing her story gave credence to naming him co-author. Otto survived World War II and didn’t pass away until 1980. That now means that the copyright could be pushed back to 2050, as he was officially deemed co-author.

certain parts of her story that he decided were unsavory or too personal. It made sense. After all, this was his daughter, and she was becoming a woman, with the curiosities of that transition. His work in editing her story gave credence to naming him co-author. Otto survived World War II and didn’t pass away until 1980. That now means that the copyright could be pushed back to 2050, as he was officially deemed co-author.

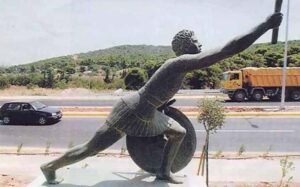

When we think of runners, most of us are impress, and rightly so. To run a race…especially a marathon…is an amazing feat. A marathon is 26.2 miles, but do you know why that is? Supposedly, the length of the race is a “tip of the hat” to a man named Pheidippides. According to legend, Pheidippides, an Athenian soldier, witnessed the combined Athenian and Spartan army’s victory over the Persians at Marathon. Then he supposedly ran 26 miles to Athens to deliver the news. When he arrived, he informed the Athenians, and then promptly perished of exhaustion. In his honor, marathon runners run 26.2 miles to remember that amazing feat, hoping not to share his fate in doing so. Another legend claims that the extra 0.2 miles were added during the 1908 Olympics so the race would end in front of Princess Mary’s pavilion. I’m not sure about the addition of the 0.2 miles, but the reality is that Pheidippides ran a lot further than 26 miles in his “death run” to spread the news of victory.

When we think of runners, most of us are impress, and rightly so. To run a race…especially a marathon…is an amazing feat. A marathon is 26.2 miles, but do you know why that is? Supposedly, the length of the race is a “tip of the hat” to a man named Pheidippides. According to legend, Pheidippides, an Athenian soldier, witnessed the combined Athenian and Spartan army’s victory over the Persians at Marathon. Then he supposedly ran 26 miles to Athens to deliver the news. When he arrived, he informed the Athenians, and then promptly perished of exhaustion. In his honor, marathon runners run 26.2 miles to remember that amazing feat, hoping not to share his fate in doing so. Another legend claims that the extra 0.2 miles were added during the 1908 Olympics so the race would end in front of Princess Mary’s pavilion. I’m not sure about the addition of the 0.2 miles, but the reality is that Pheidippides ran a lot further than 26 miles in his “death run” to spread the news of victory.

For that reason, the real Pheidippides probably wouldn’t have been impressed with someone who ran just 26.2 miles. That would have been child’s play to him. In reality, Pheidippides ran about 300 miles over the course of two days. It’s no wonder he passed away from exhaustion at the end of such a run. Pheidippides was a hemerodromos, or a military long-distance runner. Basically, he was a courier, but these days couriers use a  bicycle or car to carry their messages. Nevertheless, in ancient times, runners were the most efficient way to transmit messages over long distances, but Pheidippides’s legendary run was much, much longer than the average run. In fact, it was a “death run.”

bicycle or car to carry their messages. Nevertheless, in ancient times, runners were the most efficient way to transmit messages over long distances, but Pheidippides’s legendary run was much, much longer than the average run. In fact, it was a “death run.”

The actual task assigned to Pheidippides was to run from Athens to Sparta to ask for more soldiers to be sent. It was a task he carried out, and the Spartans agreed. However, they refused to fight until there was a full moon, as was their battle custom. That was six days away, and would be of no help, since the loss of life by then would be too great. So, Pheidippides turned around and ran back to Athens to inform his superiors of the delay. It reportedly took him two days to cover 300 miles, and it was at the end of this run that Pheidippides expired.

Supposedly, it was a different runner entirely who ran from Marathon to Athens to deliver the news about the victory. While remaining anonymous, this runner apparently still perished at the end of his journey, which is why his shorter run is still remembered. I suppose that does make the marathon a treacherous and dangerous race. Over time, Pheidippides’s ultra-marathon was combined with the anonymous runner’s feat. Maybe they thought it was impossible for a man to run 300 miles in two days, and since I’m not runner, I really couldn’t  say. For me, while I can and have regularly walked 10 to 15 miles in a day, to run even a mile would be a likely impossibility, so I have great respect for anyone who runs any distance, much less a marathon or even a half-marathon. I am not surprised that these men died at the end of their runs. Quite possibly, their water and even food supply was somewhat limited during their runs, and since I know how tired I am after walking 10 to 15 miles, I can almost imagine the exhaustion after running a marathon or half-marathon, but to run 300 miles over two days, well suffice it to say I would have dropped before the first day ended…which is probably why I don’t run…unless it is to get away from danger, hahaha!!

say. For me, while I can and have regularly walked 10 to 15 miles in a day, to run even a mile would be a likely impossibility, so I have great respect for anyone who runs any distance, much less a marathon or even a half-marathon. I am not surprised that these men died at the end of their runs. Quite possibly, their water and even food supply was somewhat limited during their runs, and since I know how tired I am after walking 10 to 15 miles, I can almost imagine the exhaustion after running a marathon or half-marathon, but to run 300 miles over two days, well suffice it to say I would have dropped before the first day ended…which is probably why I don’t run…unless it is to get away from danger, hahaha!!

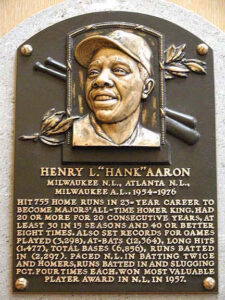

When Babe Ruth set his home run record in 1935, and because the record lasted for so many years, many people thought it would never be broken. That idea was shattered on April 8, 1974, when Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves hits his 715th career home run, breaking Babe Ruth’s legendary record of 714 homers. The game was also broadcast nationally on NBC. It was the end of an era, and many people were sad to see it happen. There was discussion that it shouldn’t count, because of the difference in bats in the 70s, as opposed to the 30s. I wasn’t a big baseball fan in those days, but I remember the argument. I’m sure there was some validity in it, but the fact that the equipment had changed was not something anyone could help. The rules allowed the newer bats, and that was that.

When Babe Ruth set his home run record in 1935, and because the record lasted for so many years, many people thought it would never be broken. That idea was shattered on April 8, 1974, when Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves hits his 715th career home run, breaking Babe Ruth’s legendary record of 714 homers. The game was also broadcast nationally on NBC. It was the end of an era, and many people were sad to see it happen. There was discussion that it shouldn’t count, because of the difference in bats in the 70s, as opposed to the 30s. I wasn’t a big baseball fan in those days, but I remember the argument. I’m sure there was some validity in it, but the fact that the equipment had changed was not something anyone could help. The rules allowed the newer bats, and that was that.

Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s record in front of a crowd of 53,775 people, the largest in the history of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. They all knew he was close, and no one wanted to miss that all-important 715th homerun. The record-breaking hit came in a 4th inning pitch off the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Al Downing. However, because Aaron, an African American, had received death threats and racist hate mail during his pursuit of one of baseball’s most distinguished records, the achievement, for him, was bittersweet.

Henry Louis Aaron Jr was born in Mobile, Alabama, on February 5, 1934. He made his Major League debut in 1954 with the Milwaukee Braves. That, in and of itself was an accomplishment, because just eight years earlier, it would not have been allowed. Then, Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier and became the first African American to play in the majors in 1947. That opened the door for Aaron, a hardworking and quiet man. He was to be the last “Negro League” player to also compete in the Major Leagues. In 1957, Aaron, who played right field, was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player as the Milwaukee Braves won the pennant. A few weeks later, his three home runs in the World Series helped his team in their win over the heavily favored New York Yankees. Although “Hammerin’ Hank” specialized in home runs, he was also an extremely dependable batter, and by the end of his career he held baseball’s career record for most runs batted in…2,297. His career lasted for 23 years. He was with the Braves from 1954 to 1974…first in Milwaukee and then in Atlanta, when the franchise moved in 1966…and closed it out with two seasons back in Milwaukee for the Brewers.

When he retired in 1976, Aaron had 755 career home runs to his credit…a record that stood until 2007, when it was broken by controversial slugger Barry Bonds (Bonds admitted to using steroids in 2011). Bonds career homeruns ended at 762, but many people think he should be stripped of the record for the illegal steroid use.

Nevertheless, Bonds baseball career was over. Hank Aaron’s achievements didn’t end when his career did, though. He went on to become one of baseball’s first African American executives, with the Atlanta Braves, and a leading spokesperson for minority hiring. Hank Aaron was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982. On January 5, 2021, Aaron publicly received a COVID-19 vaccination with the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine at the Morehouse School of Medicine at Atlanta, Georgia. Aaron died in his sleep in his Atlanta residence on January 22 at the age of 86. While the manner of death was listed as natural causes, anti-vaccine activists Robert F Kennedy Jr and Del Bigtree have suggested that Aaron’s death was caused by receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. I suppose we will never know.

Nevertheless, Bonds baseball career was over. Hank Aaron’s achievements didn’t end when his career did, though. He went on to become one of baseball’s first African American executives, with the Atlanta Braves, and a leading spokesperson for minority hiring. Hank Aaron was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982. On January 5, 2021, Aaron publicly received a COVID-19 vaccination with the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine at the Morehouse School of Medicine at Atlanta, Georgia. Aaron died in his sleep in his Atlanta residence on January 22 at the age of 86. While the manner of death was listed as natural causes, anti-vaccine activists Robert F Kennedy Jr and Del Bigtree have suggested that Aaron’s death was caused by receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. I suppose we will never know.