History

Protests are a common story these days, and the police are often kept busy for days trying to keep some kind of order. Not much has really changed in that arena. No nation is exempt from the possibility of violence breaking out because people feel they have been subjected to injustice…whether the facts bear out the belief or not. In 1926, miners across the United Kingdom went on strike. They were being subjected to an involuntary 13% wage cut, as well as an increase in weekly labor, and they were not planning to put up with it. When workers in other industries refused to work in solidarity with the striking miners, it led to a general strike. The work stoppage lasted nine days.

Protests are a common story these days, and the police are often kept busy for days trying to keep some kind of order. Not much has really changed in that arena. No nation is exempt from the possibility of violence breaking out because people feel they have been subjected to injustice…whether the facts bear out the belief or not. In 1926, miners across the United Kingdom went on strike. They were being subjected to an involuntary 13% wage cut, as well as an increase in weekly labor, and they were not planning to put up with it. When workers in other industries refused to work in solidarity with the striking miners, it led to a general strike. The work stoppage lasted nine days.

1926 was an unsettled year, with protests becoming quite common, especially  in London’s Trafalgar Square. As a result of the violence, the police wanted to set up a temporary police station, so they could keep an eye on things. The public would have none of it. Their outcry literally caused the police to drop the project. The problem, however, remained, so they knew that something had to be done. Finally, someone came up with a brilliant idea. That year, they built several large ornate light posts. One of the light posts was configured with the idea of housing what is most likely the world’s tiniest police station. This brilliant idea allowed the police to hide it, and their surveillance, in plain sight.

in London’s Trafalgar Square. As a result of the violence, the police wanted to set up a temporary police station, so they could keep an eye on things. The public would have none of it. Their outcry literally caused the police to drop the project. The problem, however, remained, so they knew that something had to be done. Finally, someone came up with a brilliant idea. That year, they built several large ornate light posts. One of the light posts was configured with the idea of housing what is most likely the world’s tiniest police station. This brilliant idea allowed the police to hide it, and their surveillance, in plain sight.

The police station pole was located inconspicuously at the south-east corner of Trafalgar Square. It is a rather  peculiar and often overlooked world record holder…Britain’s Smallest Police Station. Apparently this tiny box can accommodate up to two prisoners at a time, although its main purpose was to hold a single police officer. I guess you could say that it was a 1920’s version of the ring doorbell camera. It didn’t take video, but the officer inside could clearly watch the square. Once the light fitting was hollowed out, the builders installed a set of narrow windows in order to provide a vista across the main square. Also installed was a direct phone line back to Scotland Yard in case reinforcements were needed in times of trouble. In fact, whenever the police phone was picked up, the ornamental light fitting at the top of the box started to flash, alerting any nearby officers on duty that trouble was near. It was a brilliant idea, but as with all inventions, their usefulness lasts only until the next big thing comes along. Such was the case with the Trafalgar Square Light Pole Police Station. Eventually new technology made the little station obsolete. Today the pole is used for custodial storage.

peculiar and often overlooked world record holder…Britain’s Smallest Police Station. Apparently this tiny box can accommodate up to two prisoners at a time, although its main purpose was to hold a single police officer. I guess you could say that it was a 1920’s version of the ring doorbell camera. It didn’t take video, but the officer inside could clearly watch the square. Once the light fitting was hollowed out, the builders installed a set of narrow windows in order to provide a vista across the main square. Also installed was a direct phone line back to Scotland Yard in case reinforcements were needed in times of trouble. In fact, whenever the police phone was picked up, the ornamental light fitting at the top of the box started to flash, alerting any nearby officers on duty that trouble was near. It was a brilliant idea, but as with all inventions, their usefulness lasts only until the next big thing comes along. Such was the case with the Trafalgar Square Light Pole Police Station. Eventually new technology made the little station obsolete. Today the pole is used for custodial storage.

It seems an impossible task, to keep a disaster a secret, and yet that is exactly what the Soviet Union tried to do when disaster struck on April 26, 1986, at the No. 4 reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near the city of Pripyat in the north of the Ukrainian SSR. Chernobyl is considered the worst nuclear disaster in history. In terms of cost and casualties, and it is one of only two nuclear energy accidents rated at seven, which is the maximum severity, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The other disaster was the well known 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan that was caused by a tsunami.

It seems an impossible task, to keep a disaster a secret, and yet that is exactly what the Soviet Union tried to do when disaster struck on April 26, 1986, at the No. 4 reactor in the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, near the city of Pripyat in the north of the Ukrainian SSR. Chernobyl is considered the worst nuclear disaster in history. In terms of cost and casualties, and it is one of only two nuclear energy accidents rated at seven, which is the maximum severity, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The other disaster was the well known 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan that was caused by a tsunami.

On April 28, 1986, two days after monitoring stations in Sweden, Finland and Norway began reporting sudden high discharges of radioactivity in the atmosphere, the Soviet Union finally broke the news by way of their official news agency, Tass. Two days!! In the realm of nuclear contamination, two days is an eternity!! When the Soviet Union finally told the world, Tass simply said there had been an accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine. They didn’t say they had tried to hide it, but two days of no response tells me they did. The initial emergency response, together with later decontamination of the environment, ultimately involved more than 500,000 personnel and cost an estimated 18 billion Soviet rubles, which is roughly $68 billion US dollars as of the dollar value in 2019.

It was determined that the accident had started during a safety test on an RBMK-type nuclear reactor. During testing a simulation of an electrical power outage was used to help create a safety procedure for maintaining reactor cooling water circulation until the back-up electrical generators could provide power. These units had been tested three times since 1982, but they had failed to provide a solution. On this fourth attempt, an unexpected 10-hour delay meant that an unprepared operating shift was on duty. The power unexpectedly dropped to a near-zero level during the planned decrease of reactor power in preparation for the electrical test. The operators were only able to partially restore the specified test power, putting the reactor in an unstable condition. This risk was not made evident in the operating instructions, so the operators proceeded with the electrical test. Upon test completion, the operators triggered a reactor shutdown, but a combination of unstable conditions and reactor design flaws caused an uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction instead.

The failure caused a large amount of energy to be suddenly released, followed by two explosions that ruptured  the reactor core and destroyed the reactor building. One was a highly destructive steam explosion from the vaporizing superheated cooling water. The other explosion could have been another steam explosion or a small nuclear explosion, like a nuclear fizzle. The explosions were followed immediately by an open-air reactor core fire that released considerable airborne radioactive contamination for about nine days. The contamination fell onto parts of the USSR and western Europe, especially 10 miles away in Belarus, where around 70% landed, before finally being contained on May 4, 1986. In addition to the contamination released by the explosions, the fire gradually released about the same amount of contamination as did the initial explosion. As a result of rising radiation levels in surrounding regions, a 6.2 mile radius exclusion zone was created 36 hours after the accident. About 49,000 people were evacuated from the area, primarily the citizens of Pripyat. Later the exclusion zone was increased to 19 mile radius, and an additional 68,000 people were evacuated from the wider area.

the reactor core and destroyed the reactor building. One was a highly destructive steam explosion from the vaporizing superheated cooling water. The other explosion could have been another steam explosion or a small nuclear explosion, like a nuclear fizzle. The explosions were followed immediately by an open-air reactor core fire that released considerable airborne radioactive contamination for about nine days. The contamination fell onto parts of the USSR and western Europe, especially 10 miles away in Belarus, where around 70% landed, before finally being contained on May 4, 1986. In addition to the contamination released by the explosions, the fire gradually released about the same amount of contamination as did the initial explosion. As a result of rising radiation levels in surrounding regions, a 6.2 mile radius exclusion zone was created 36 hours after the accident. About 49,000 people were evacuated from the area, primarily the citizens of Pripyat. Later the exclusion zone was increased to 19 mile radius, and an additional 68,000 people were evacuated from the wider area.

When the reactor exploded, two of the reactor operating staff lost their lives instantly. Crews rushed to put out the fire, stabilize the reactor, and cleanup the ejected nuclear core. As a result of the disaster and immediate response, 134 station staff and firemen were hospitalized with acute radiation syndrome due to absorbing high doses of ionizing radiation. In the days to months afterward 28 of these 134 people died, and approximately 14 suspected radiation-induced cancer deaths followed within the next 10 years. Significant cleanup operations were taken in the exclusion zone to deal with local fallout, and the exclusion zone was made permanent. The cities in the zone remain abandoned.

By 2011, an excess of 15 childhood thyroid cancer deaths were documented among the wider population. The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) has reviewed all the published research on the incident multiple times, and found that at present, fewer than 100 documented deaths are likely to be attributable to increased exposure to radiation. Of course, there is no way to be sure of that information, because “determining the total eventual number of exposure related deaths is uncertain based on the linear no-threshold model, a contested statistical model, which has also been used in estimates of low level radon and air pollution exposure.” When the expected deaths is viewed in “model predictions with the greatest confidence values of the eventual total death toll in the decades ahead from Chernobyl releases vary, from 4,000 fatalities when solely assessing the three most contaminated former Soviet states, to about 9,000 to 16,000 fatalities when assessing the total continent of Europe. In an effort to reduce the spread of radioactive contamination from the wreckage and protect it from weathering, the protective Chernobyl Nuclear  Power Plant sarcophagus was built by December 1986. It also provided radiological protection for the crews of the undamaged reactors at the site, which continued operating. Due to the continued deterioration of the sarcophagus, it was further enclosed in 2017 by the Chernobyl New Safe Confinement, a larger enclosure that allows the removal of both the sarcophagus and the reactor debris, while containing the radioactive hazard. Nuclear clean-up is scheduled for completion in 2065.” It is my opinion that if they had acted immediately to evacuate the people in surrounding areas, they might have reduced the number of deaths substantially. Keeping the accident a secret for two days was insane, and very likely criminal.

Power Plant sarcophagus was built by December 1986. It also provided radiological protection for the crews of the undamaged reactors at the site, which continued operating. Due to the continued deterioration of the sarcophagus, it was further enclosed in 2017 by the Chernobyl New Safe Confinement, a larger enclosure that allows the removal of both the sarcophagus and the reactor debris, while containing the radioactive hazard. Nuclear clean-up is scheduled for completion in 2065.” It is my opinion that if they had acted immediately to evacuate the people in surrounding areas, they might have reduced the number of deaths substantially. Keeping the accident a secret for two days was insane, and very likely criminal.

The race to space was not without the unfortunate casualties here and there. Nevertheless, as a whole, it has been a very safe program. The first deaths experienced by the United States, in the NASA program were those of Command Pilot Gus Grissom, Senior Pilot Ed White, and Pilot Roger Chaffee on January 27, 1967, when he Command Module interior caught fire and burned, during a pre-launch test on Launch Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy. At that time there was no interior latch, so the men could not escape the burning module. It was a terrible tragedy for the NASA program and the nation as a whole. The United States had been involved in a “race to space” with the Soviet Union, and the fire was a terrible setback…not to mention the horrific loss of life.

The race to space was not without the unfortunate casualties here and there. Nevertheless, as a whole, it has been a very safe program. The first deaths experienced by the United States, in the NASA program were those of Command Pilot Gus Grissom, Senior Pilot Ed White, and Pilot Roger Chaffee on January 27, 1967, when he Command Module interior caught fire and burned, during a pre-launch test on Launch Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy. At that time there was no interior latch, so the men could not escape the burning module. It was a terrible tragedy for the NASA program and the nation as a whole. The United States had been involved in a “race to space” with the Soviet Union, and the fire was a terrible setback…not to mention the horrific loss of life.

On April 24, 1967, just a few short months later, the Soviet Union also experienced a tragic set back, when Soviet Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov is killed when his parachute failed to deploy during his spacecraft’s landing. Komarov, a fighter pilot and aeronautical engineer, was testing the spacecraft Soyuz I at the time of the catastrophic failure of the parachute. He had made his first space trip in 1964, three years before the doomed 1967 voyage. After 24 hours and 16 orbits of the earth in Soyuz I, Komarov was scheduled to reenter the atmosphere, but ran into difficulty handling the vessel and was unable to fire the rocket brakes. It took two more trips around the earth before the cosmonaut could manage reentry. When Soyuz I reached an altitude of 23,000 feet, a parachute was supposed to deploy, bringing Komarov safely to earth. Unfortunately, the maneuvering problems he had caused the lines of the chute had gotten tangled and there was no backup chute. When Soyuz I reached an altitude of 23,000 feet, a parachute was supposed to deploy, bringing Komarov safely to earth. Komarov plunged to the ground and was killed.

Things in the Soviet Union were different than in the United States, and Komarov’s wife had not been told of the Soyuz I launch until after Komarov was already in orbit. Sadly, she did not get to say goodbye to her husband. Komarov was considered a national hero, and there was vast public mourning in Moscow. Komarov’s

ashes were buried in the wall of the Kremlin. Space flight is dangerous, a fact that is well known to all who venture into its corridors. Despite the dangers, both the Soviet Union and the United States continued their space exploration. The United States landed men on the moon just two years later. Everyone was determined to see the program through, as they continue to be to this day.

ashes were buried in the wall of the Kremlin. Space flight is dangerous, a fact that is well known to all who venture into its corridors. Despite the dangers, both the Soviet Union and the United States continued their space exploration. The United States landed men on the moon just two years later. Everyone was determined to see the program through, as they continue to be to this day.

There are many trails or roads that stretch across this world that seem to be simply a way to get from point A to point B, and indeed, that is what many of them are, but there are some that hold a very different meaning. One such road is the Great Ocean Road in southern Australia. The Great Ocean Road is an Australian National Heritage listed 151 mile stretch of road along the south-eastern coast of Australia between the Victorian cities of Torquay and Allansford. The road was built by soldiers who had returned from war between 1919 and 1932 and dedicated to soldiers killed during World War I. The Great Ocean Road is the world’s largest war memorial. It is an interesting kind of memorial, winding through varying terrain along the coast and providing access to several prominent landmarks, including the Twelve Apostles limestone stack formations. The road is an important tourist attraction in the region.

There are many trails or roads that stretch across this world that seem to be simply a way to get from point A to point B, and indeed, that is what many of them are, but there are some that hold a very different meaning. One such road is the Great Ocean Road in southern Australia. The Great Ocean Road is an Australian National Heritage listed 151 mile stretch of road along the south-eastern coast of Australia between the Victorian cities of Torquay and Allansford. The road was built by soldiers who had returned from war between 1919 and 1932 and dedicated to soldiers killed during World War I. The Great Ocean Road is the world’s largest war memorial. It is an interesting kind of memorial, winding through varying terrain along the coast and providing access to several prominent landmarks, including the Twelve Apostles limestone stack formations. The road is an important tourist attraction in the region.

The road would likely have been a huge tourist attraction, without the memorial as part of the attraction. I has gorgeous views of the ocean, as well as lighthouses along the way. It can be driven the entire way, but there are trails to walk along it as well, which would really be the thing I would find interesting. Along the way you can see limestone formations like the Twelve Apostles, but also one called the London Arch. It used to be the London Bridge, so I wonder if it was connected to the land at one time. The area has also been well known for shipwrecks, in fact, it is called the Shipwreck Coast. Ships wrecked there include Thistle (1837), Children (1839), Unknown French whaler (1841), Lydia (1843), Socrates (1843), Cataraqui (1845), Enterprise (1850), Essington (1852), Freedom (1853), SS Schomberg (built Liverpool, named after Charles Frederick Schomberg, sunk 1855), John Scott (1858), Golden Spring (1863), Marie Gabrielle (1869), Young Australian (1877), Loch Ard (1878), Napier (1878), Alexandra (1882), Yarra (1882), Edinburgh Castle (1888), Fiji (1891), Joseph H. Scammell (1891), Newfield (1892), Freetrader (1894), La Bella (1905), Falls of Halladale (1908), The Speculant (1911), Antares (1914), Casino (1932), and City of Rayville (1940), among others. Over 50 shipwrecks are commemorated in a Historic Shipwreck Trail beginning at Port Fairy.

There are a number of tourist attractions along the Great Ocean Road, besides the Shipwreck Coast west of Cape Otway, including the Surf Coast, between Torquay and Cape Otway, providing visibility of Bass Strait and the Southern Ocean. The road winds through rainforests, as well as beaches and cliffs made of limestone and

sandstone, which is susceptible to erosion…hence the limestone stacks. As the Great Ocean Road nears Geelong, the road moves along the coast, with tall, almost-vertical cliffs on the other side of it. Of course, there is the possibility of falling rocks, but it doesn’t deter the tourists. I have never had the pleasure of being a tourist along that beautiful stretch of road, but I really think I might enjoy it if I ever got the chance.

sandstone, which is susceptible to erosion…hence the limestone stacks. As the Great Ocean Road nears Geelong, the road moves along the coast, with tall, almost-vertical cliffs on the other side of it. Of course, there is the possibility of falling rocks, but it doesn’t deter the tourists. I have never had the pleasure of being a tourist along that beautiful stretch of road, but I really think I might enjoy it if I ever got the chance.

Many people know that April 20th is Hitler’s birthday, not that most of us would celebrate that fact. Nevertheless, for the Allies in World War II, at least on April 20, 1945, that day meant something. Not because it was Hitler’s birthday…no, it was because the Allies had a plan. The Germans had been in control in much of Italy, and their advancement had to be stopped. As always, there were multiple campaigns planned on any given day in the war. One planned attack, called Operation Corncob, was to send Allied bombers into Italy to begin a three-day attack on the bridges over the rivers Adige and Brenta to cut off the German lines of possible retreat on the peninsula. They knew that Hitler would be otherwise occupied, it being his birthday and all…and so he was.

Many people know that April 20th is Hitler’s birthday, not that most of us would celebrate that fact. Nevertheless, for the Allies in World War II, at least on April 20, 1945, that day meant something. Not because it was Hitler’s birthday…no, it was because the Allies had a plan. The Germans had been in control in much of Italy, and their advancement had to be stopped. As always, there were multiple campaigns planned on any given day in the war. One planned attack, called Operation Corncob, was to send Allied bombers into Italy to begin a three-day attack on the bridges over the rivers Adige and Brenta to cut off the German lines of possible retreat on the peninsula. They knew that Hitler would be otherwise occupied, it being his birthday and all…and so he was.

Hitler was actually occupied for more reasons than just his birthday, as Soviet artillery had begun shelling Berlin at 11am on his 56th birthday. Preparations were being made to evacuate Hitler and his staff to Obersalzberg to make a final stand in the Bavarian mountains, but Hitler refused to leave his bunker. So, Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler left the bunker for the last time. Operation Herring had begun the day before, with American aircraft dropping Italian paratroopers over Northern Italy, and with Operation Corncob came the other half of the attack, which was to remove the bridges and thereby halt the expected retreat of the German forces. I doubt if Hitler knew anything about these attacks, I’m sure his mind was on his upcoming suicide, a death which some say didn’t really take place, and a fact which we will never know for sure.

The Allied attacks of April 1945 on the Italian front, were intended to end the Italian campaign and the war in Italy, and to decisively break through the German Gothic Line, the defensive line along the Apennines and the River Po plain to the Adriatic Sea and swiftly drive north to occupy Northern Italy and get to the Austrian and Yugoslav borders as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, German strongpoints, as well as bridge, road, levee and dike blasting, and any occasional determined resistance in the Po Valley plain slowed the planned sweep down. Allied planners decided that dropping paratroops into some key areas and locales south of the River Po might help wreak havoc in the German rear area, attack German communications, and vehicle columns, further disrupting the German retreat, and prevent German engineers from blowing up key structures before Allied spearheads could exploit them. Lieutenant General Sir Richard McCreery, commander of the Commonwealth 8th Army, had a number of Italian paratroopers at hand for the task.

Meanwhile, Adolf Hitler celebrated his 56th birthday with a traditional parade and full celebration, while a

Gestapo reign of terror took the lives by hanging of 20 Russian prisoners of war and 20 Jewish children, at least nine of which were under the age of 12. All of the victims had been taken from Auschwitz to Neuengamme, the place of execution, for the purpose of medical experimentation. Hitler and his Third Reich didn’t fully understand it then, but they were finished, and the end was coming quickly.

Gestapo reign of terror took the lives by hanging of 20 Russian prisoners of war and 20 Jewish children, at least nine of which were under the age of 12. All of the victims had been taken from Auschwitz to Neuengamme, the place of execution, for the purpose of medical experimentation. Hitler and his Third Reich didn’t fully understand it then, but they were finished, and the end was coming quickly.

April 19, 1995 was a normal spring morning in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, but by 9:02am, all that would change forever. This was the day that antigovernment extremists, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols had chosen to tell the world that they didn’t like things going the way they were. The biggest problem was not that they wanted to protest, because that is their right, but it was the way they chose to protest that was completely criminal.

April 19, 1995 was a normal spring morning in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, but by 9:02am, all that would change forever. This was the day that antigovernment extremists, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols had chosen to tell the world that they didn’t like things going the way they were. The biggest problem was not that they wanted to protest, because that is their right, but it was the way they chose to protest that was completely criminal.

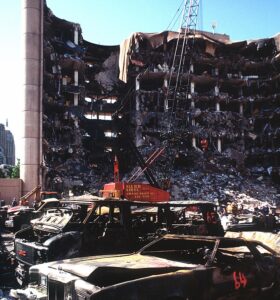

That morning, McVeigh parked a Ryder truck in front of the Alfred P Murrah Federal Building and then, he walked away. No warning was issued, because nothing was considered to be out of place, but that day about a thousand people started their day in the building, only to have their lives forever changed, or ended. The bomb went off at 9:02am, and in that moment, more than one-third of the building was destroyed, 168 people lost their lives, and about 800 were injured. The dead included 19 children in the on-site daycare facility. The blast destroyed or damaged 324 other buildings within a 16-block radius, shattered glass in 258 nearby buildings, and destroyed or burned 86 cars, causing an estimated $652 million worth of damage. In response to the attack, local, state, federal, and worldwide agencies quickly mobilized in extensive rescue. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) activated 11 of its Urban Search and Rescue Task Forces, consisting of 665 rescue workers who assisted in rescue and recovery operations.

The investigation moved rapidly, and within 90 minutes of the explosion, McVeigh was stopped by Oklahoma Highway Patrolman Charlie Hanger for driving without a license plate and arrested for illegal weapons possession. It seems that most criminals make mistakes that lead to their downfall. Forensic evidence quickly

linked McVeigh and Nichols to the attacks. Nichols was arrested and within days, both were charged. Michael and Lori Fortier were later identified as co-conspirators. McVeigh, a veteran of the Gulf War and a sympathizer with the US militia movement, had detonated the Ryder rental truck filled with explosives and Nichols had assisted with the bomb’s preparation. Motivated by his dislike for the US federal government and unhappy about its handling of the Ruby Ridge incident in 1992 and the Waco siege in 1993, McVeigh timed his attack to coincide with the second anniversary of the fire that ended the siege at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas.

linked McVeigh and Nichols to the attacks. Nichols was arrested and within days, both were charged. Michael and Lori Fortier were later identified as co-conspirators. McVeigh, a veteran of the Gulf War and a sympathizer with the US militia movement, had detonated the Ryder rental truck filled with explosives and Nichols had assisted with the bomb’s preparation. Motivated by his dislike for the US federal government and unhappy about its handling of the Ruby Ridge incident in 1992 and the Waco siege in 1993, McVeigh timed his attack to coincide with the second anniversary of the fire that ended the siege at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas.

I could never understand why terrorists consider it necessary to take out so many innocent lives in order to make their grievances known. The official FBI investigation was known as “OKBOMB” involved 28,000 interviews, 3.5 short tons of evidence and nearly one billion pieces of information. The bombers were tried and convicted in 1997. McVeigh was sentenced to death, and was executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001, at the US federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana. Nichols was sentenced to life in prison in 2004. Michael and Lori Fortier testified against McVeigh and Nichols, in exchange for a plea-deal. Michael Fortier was sentenced to 12 years in prison for failing to warn the United States government, and Lori received immunity from prosecution in exchange for her testimony. Michael was released into witness protection in 2006.

The US Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, which tightened the standards for habeas corpus in the United States n response to the bombing. It also passed legislation to increase the protection around federal buildings to deter future terrorist attacks. Prior to the September 11th attacks in 2001, the Oklahoma City bombing was the deadliest terrorist attack in the history of the United

States, other than the Tulsa race massacre. It remains one of the deadliest acts of domestic terrorism in US history. On April 19, 2000, the Oklahoma City National Memorial was dedicated on the site of the Murrah Federal Building, commemorating the victims of the bombing. Remembrance services are held every year on April 19, at the time of the explosion.

States, other than the Tulsa race massacre. It remains one of the deadliest acts of domestic terrorism in US history. On April 19, 2000, the Oklahoma City National Memorial was dedicated on the site of the Murrah Federal Building, commemorating the victims of the bombing. Remembrance services are held every year on April 19, at the time of the explosion.

Henri Honoré Giraud was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944. Giraud was born on January 18, 1879 the son of Louis and Jeanne (née Deguignand) Giraud. His father was a coal merchant. Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from the Saint-Cyr military academy and served in French North Africa. During World War I, Giraud was wounded and captured by the Germans, but managed to escape from his prisoner-of-war camp. It was the first time he escaped, but not the last. After World War I ended, Giraud returned to North Africa and fought in the Rif War. During that war, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. The Légion d’honneur (or Legion of Honour) is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. It was established in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte, and it has been retained by all later French governments and régimes.

Henri Honoré Giraud was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944. Giraud was born on January 18, 1879 the son of Louis and Jeanne (née Deguignand) Giraud. His father was a coal merchant. Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from the Saint-Cyr military academy and served in French North Africa. During World War I, Giraud was wounded and captured by the Germans, but managed to escape from his prisoner-of-war camp. It was the first time he escaped, but not the last. After World War I ended, Giraud returned to North Africa and fought in the Rif War. During that war, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. The Légion d’honneur (or Legion of Honour) is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. It was established in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte, and it has been retained by all later French governments and régimes.

When World War II began, Giraud was a member of the Superior War Council. He strongly disagreed with Charles de Gaulle about the tactics of using armored troops that were planned. Giraud was made the commander of the 7th Army when it was sent to the Netherlands on May 10, 1940. He was able to delay German troops at Breda on May 13th. The badly depleted 7th Army was then merged with the 9th Army. While the troops were trying to block a German attack through the Ardennes, Giraud was at the front with a reconnaissance patrol when he was captured by German troops at Wassigny on May19th. A German court-martial tried Giraud for ordering the execution of two German saboteurs wearing civilian clothes, but he was acquitted and taken to Königstein Castle near Dresden, which was used as a high-security POW prison. He would be held there for two years.

Not one to just sit around, Giraud began carefully planning his escape. He learned German and memorized a map of the area. He painstakingly made a 150 feet rope out of twine, torn bedsheets, and copper wire, which friends had smuggled into the prison for him. Using a simple code embedded in his letters home, he informed his family of his plans to escape. I doubt if they were surprised, as it would not be the first time he escaped his captors. Finally on April 17, 1942, he was ready. Königstein Castle was built on a hilltop, with steep cliff on one side. After shaving off his moustache and covering his head with a Tyrolean hat to disguise himself, Giraud lowered himself down the cliff of the mountain fortress. He discretely travelled to Schandau where he met his Special Operations Executive (SOE) contact, who provided him with a change of clothes, cash, and identity papers. Thus began the series of tactics designed to get Giraud to the Swiss border by train. By now, the border guards had been informed of his escape and were on the alert for him. Giraud walked through the mountains until he was stopped by two Swiss soldiers, who took him to Basel. Eventually, he was able to slip into Vichy France, where he was finally able to make his identity known. He tried unsuccessfully to convince Marshal Pétain that Germany would lose, and that France must resist the German occupation. His views were rejected, but at least the Vichy government refused to return Giraud to the Germans. Returning him would have been a death sentence, because Hitler had ordered Giraud’s assassination upon being caught. Giraud went to North Africa via a British submarine, and joined the French Free Forces under General Charles de Gaulle. He eventually helped to rebuild the French army.

In January 1943, Giraud took part in the Casablanca Conference along with Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill, and Franklin D Roosevelt. Later in the same year, Giraud and de Gaulle became co-presidents of the French Committee of National Liberation, but Giraud lost support and retired in frustration in April 1944. After

the war, Giraud was elected to the Constituent Assembly of the French Fourth Republic. He remained a member of the War Council and was decorated for his escape. He published two books, “Mes Evasions” (My Escapes, 1946) and “Un seul but, la victoire”: Alger 1942–1944 (A Single Goal, Victory: Algiers 1942–1944, 1949) about his experiences. He died in Dijon on March 11, 1949.

the war, Giraud was elected to the Constituent Assembly of the French Fourth Republic. He remained a member of the War Council and was decorated for his escape. He published two books, “Mes Evasions” (My Escapes, 1946) and “Un seul but, la victoire”: Alger 1942–1944 (A Single Goal, Victory: Algiers 1942–1944, 1949) about his experiences. He died in Dijon on March 11, 1949.

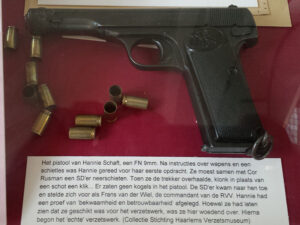

When thinking of spies, our minds might logically think of James Bond 007 or some of the NCIS shows, but we somehow don’t think of women…at least not very often. Nevertheless, the truth is there are many women who are spies, and some of them were in the era of World War II. These women were gutsy. They faced danger defiantly. Jannetie “Hannie” Schaft was a Dutch resistance fighter during World War II. She could have done like so many others, and obediently taken the oath of loyalty to the Nazis. Her life would have gone on somewhat like it had before.

When thinking of spies, our minds might logically think of James Bond 007 or some of the NCIS shows, but we somehow don’t think of women…at least not very often. Nevertheless, the truth is there are many women who are spies, and some of them were in the era of World War II. These women were gutsy. They faced danger defiantly. Jannetie “Hannie” Schaft was a Dutch resistance fighter during World War II. She could have done like so many others, and obediently taken the oath of loyalty to the Nazis. Her life would have gone on somewhat like it had before.

Schaft was born in Haarlem, which is the capital of the province of North Holland. Her mother was Aafje Talea Schaft (née Vrijer), who was a Mennonite woman. Her father, Pieter Schaft was attached to the Social Democratic Workers’ Party. Schaft led a sheltered life, because her parents were very protective of her following the death of her older sister. Her sheltered upbringing did not affect her personality. She was as  bold and defiant as ever. When the Nazis wanted the people to swear allegiance to them, Schaff refused to do so. Instead, she joined Raad van Verzet, a resistance group with a communist ideology. I find it hard to think about communism being considered better than socialism, but many have considered it so. In her work for Raad van Verzet, Schaft spied on soldier activity, aided refuges, and sabotaged targets. She was very capable, and feared by many. Her work gained her the reputation as “the girl with the red hair.” While it was only a nickname, it would end up being her downfall.

bold and defiant as ever. When the Nazis wanted the people to swear allegiance to them, Schaff refused to do so. Instead, she joined Raad van Verzet, a resistance group with a communist ideology. I find it hard to think about communism being considered better than socialism, but many have considered it so. In her work for Raad van Verzet, Schaft spied on soldier activity, aided refuges, and sabotaged targets. She was very capable, and feared by many. Her work gained her the reputation as “the girl with the red hair.” While it was only a nickname, it would end up being her downfall.

Having a reputation based on the color of your hair could be a good thing. All you have to do is color your hair, and you have the perfect disguise…right? Well, it did work for a time. Schaft colored her hair to cover up the red, but then she was captured by the Nazis. They had no idea who they had, but as her hair began to grow out they quickly figured it out. Once the Germans discovered that they had the legendary spy and resistance fighter in captivity, I’m sure she was brutally beaten and tortured for information. Schaft was then executed on April 17, 1945. Schaft was never a quitter and she wouldn’t quit now. Defiant to the end, she began taunting the soldier who shot her in the head, but merely grazed her. She said, “I can shoot better than that.” The second shot killed her, but not before leaving an everlasting impression on her captors and witnesses. Schaft was just 24 years old when she died. She was given a state funeral after the war, attended by Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch royal family.

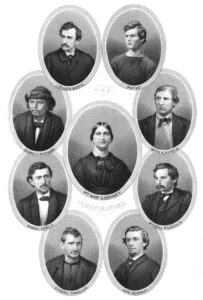

When I think of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, I think of John Wilkes Booth shooting the president at the Ford Theater. I don’t think about the assassination being a part of a conspiracy, but in fact, it was. It makes sense, I guess, because it isn’t even logical that someone could simply walk into the Ford Theater and to the President’s box and shoot him. Someone had to tell Booth where the president was going to be. Someone had to clear the way for Booth to get in. Someone had to remove more than just a president. This was a plot to change history.

When I think of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, I think of John Wilkes Booth shooting the president at the Ford Theater. I don’t think about the assassination being a part of a conspiracy, but in fact, it was. It makes sense, I guess, because it isn’t even logical that someone could simply walk into the Ford Theater and to the President’s box and shoot him. Someone had to tell Booth where the president was going to be. Someone had to clear the way for Booth to get in. Someone had to remove more than just a president. This was a plot to change history.

Lincoln conspirator Mary Surratt, who was born Mary Elizabeth Jenkins in 1823, was from Maryland. Before her acts of treason, Mary married John Harrison Surratt in 1840, when she was 17. They planed a life together an began buying massive amounts of land near Washington. Together, she and her husband had three children…John Jr, Isaac, Anna. Then After her husband’s death in 1864, when she was just 41, Mary moved to Washington DC, on High Street. To make some money, Mary rented part of her property…a tavern that her husband had built, to a man named John Lloyd, who was a retired police officer.

John Jr, Mary’s eldest son, met John Wilkes Booth during his time as a Confederate spy. Because of this connection, when Booth was plotting Lincoln’s assassination with his co-conspirators, he felt perfectly at home in Mary Surratt’s DC residence, which had by this time, become a boardinghouse. As plans progresses Mary Surratt also became involved with the shooting of Abraham Lincoln, through these men. She even asked Lloyd to help. Her request was that he have some “shooting-irons” ready for some men that would stop by later that night…the night that they murdered Abraham Lincoln. Although drunk, Lloyd was able to provide testimony of the appearance of Booth and a co-conspirator at Mary’s tavern. For her involvement, Mary Surratt was sentenced to death, she was the first woman to be executed by the United States Government. She asked of her executioners only to, “not let her fall” in a very small voice, but as she was hanged on July 7, 1865, her request was not honored.

Lewis Powell (some accounts say Paine) was nicknamed Doc as a child for his love of nursing animals back to health. Powell’s part in the conspiracy was to assassinate Secretary of State Seward. Seward was at home sick in bed the night of the assassination. That should have made his job easier. Powell gained entry to the home claiming to have medicine for Seward, but when he entered Seward’s room, he found Seward’s son, Franklin. They got into a scuffle when Powell refused to hand over the medicine. Powell beat Franklin so badly that he

was in a coma for sixty days. He also stabbed Seward’s body guard before stabbing Steward several times. He was pulled off the Secretary by the body guard and two other members of the household. Seward survived, and Powell hid in a cemetery overnight. He was caught when he returned to Mary Surratt’s while she was being questioned by investigators. Powell attempted suicide while waiting for a verdict. He was convicted and hanged on July 7, 1865.

was in a coma for sixty days. He also stabbed Seward’s body guard before stabbing Steward several times. He was pulled off the Secretary by the body guard and two other members of the household. Seward survived, and Powell hid in a cemetery overnight. He was caught when he returned to Mary Surratt’s while she was being questioned by investigators. Powell attempted suicide while waiting for a verdict. He was convicted and hanged on July 7, 1865.

David Herold accompanied Powell to Seward’s house. Herold waited outside with the getaway horses. After Lincoln was assassinated, Herold managed to escape DC that same night, and met up with Booth. He was caught with Booth on April 26. Despite his lawyers many attempts to convince the court his client was innocent, Herold was convicted and was hanged on July 7, 1865.

George Atzerodt was given the task of killing Vice President Johnson. He went to the hotel Johnson was staying at, but was too afraid to kill the vice president. He went to the hotel bar and began drinking, hoping to get his courage up to do his part. Instead, he got very drunk and spent the night wandering the streets of Washington DC. He was arrested after the bartender reported his strange questions the night before. Atzerodt was convicted and hanged on July 7, 1865.

Edman Spangler was at Ford’s Theater the night of the assassination. Witness testimonies were conflicting as to his role in covering up Booth’s escape, but he allegedly took down the man trying to catch Booth before he fled. Spangler was found guilty and sentenced to six years in prison. He was pardoned in 1869 by President Johnson…which is odd considering the group tried to kill him. Spangler died in 1875 on his farm in Maryland.

Samuel Arnold was not involved in the April 14 assassination attempts. However, he was involved in earlier plots to kidnap Lincoln, and was arrested for his connections to Booth. Arnold was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. He was pardoned by President Johnson in 1869. He died in 1906 from tuberculosis.

It is unclear what role Michael O’Laughlen played in the actual assassination attempts. He was surely a conspirator to the group’s plans. He voluntarily surrendered on April 17. O’Laughlen was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. He died from yellow fever two years into his sentence.

It is unclear what part, if any, Mary’s son, John Surratt Jr played in the events of April 14. He claims to have been in New York that night, but he escaped to Canada and an international manhunt ensued for him. After his mother’s execution in July, he escaped to England. He then traveled to Rome and joined the group of soldiers protecting the Pope. It was while visiting Alexandria, Egypt that he was finally recognized and sent back to the United States. Unlike the other co-conspirators, Surratt was tried by a civilian court. On August 10 the trial ended with a hung jury and the charges were dropped in 1868. He died from pneumonia in 1916, and was the last living person with ties to the assassination attempt.

When RMS Titanic went down on April 15, 1912, after hitting an iceberg on April 14, 1912, it was a very different time than it is today. The sinking of a ship is a terrible tragedy, and often, there is so much panic. In 1912, there was a hard and fast rule in a shipwreck situation…women and children first. The only men allowed in the lifeboats were men needed as auxiliary seamen to man the lifeboats. Charles Herbert Lightoller was born March 30, 1874 into a family that had operated cotton-spinning mills in Lancashire since the late 18th century. His mother, Sarah Jane Lightoller (née Widdows), died of scarlet fever shortly after giving birth to him. His father, Frederick James Lightoller, emigrated to New Zealand when Charles was 10, leaving him in the care of extended family. Lightoller was a British Royal Navy officer and the second officer on board the RMS Titanic. He was also the most senior member of the crew to survive the Titanic disaster. Lightoller was the officer in charge of loading passengers into lifeboats on the port side. It was no easy task, because people were in a severe state of panic. Other seamen were launching lifeboats that were not filled to capacity, and since the ship did not have nearly enough lifeboats for all the people onboard. It is possible that orders that specifically said, “women and children only” may have been the reason so many lifeboats were launched before they were filled to capacity. I’m not sure if that is true or not, but if it was the case, it is a very sad revelation. It is also possible that as many as 400 more people could have been rescued, had the order been worded just slightly different. Nevertheless, Lightoller was following the orders as given to him, and not questioning the command.

When RMS Titanic went down on April 15, 1912, after hitting an iceberg on April 14, 1912, it was a very different time than it is today. The sinking of a ship is a terrible tragedy, and often, there is so much panic. In 1912, there was a hard and fast rule in a shipwreck situation…women and children first. The only men allowed in the lifeboats were men needed as auxiliary seamen to man the lifeboats. Charles Herbert Lightoller was born March 30, 1874 into a family that had operated cotton-spinning mills in Lancashire since the late 18th century. His mother, Sarah Jane Lightoller (née Widdows), died of scarlet fever shortly after giving birth to him. His father, Frederick James Lightoller, emigrated to New Zealand when Charles was 10, leaving him in the care of extended family. Lightoller was a British Royal Navy officer and the second officer on board the RMS Titanic. He was also the most senior member of the crew to survive the Titanic disaster. Lightoller was the officer in charge of loading passengers into lifeboats on the port side. It was no easy task, because people were in a severe state of panic. Other seamen were launching lifeboats that were not filled to capacity, and since the ship did not have nearly enough lifeboats for all the people onboard. It is possible that orders that specifically said, “women and children only” may have been the reason so many lifeboats were launched before they were filled to capacity. I’m not sure if that is true or not, but if it was the case, it is a very sad revelation. It is also possible that as many as 400 more people could have been rescued, had the order been worded just slightly different. Nevertheless, Lightoller was following the orders as given to him, and not questioning the command.

When all the lifeboats were launched, and the crew and remaining passengers knew the Titanic was surely going down, Lightoller and his fellow officers “all shook hands and said ‘Good-bye’” as they saw the last lifeboat off. Lightoller then dove into the frigid water from the bridge choosing to take his chances in the water, rather than the ship. Miraculously he managed to avoid being sucked down along with the massive ship. He clung to an nearby overturned lifeboat until the survivors were rescued. Lightoller was the last person pulled aboard the Carpathia and the highest-ranking officer to survive the wreck. One might imagine that surviving the greatest  maritime disaster of the 20th century would have made Charles Lightoller give up the sea forever, but he was not a man to let a little thing like having a ship ripped out from under him end his adventures at sea. No, he was not even close to being done with the sea.

maritime disaster of the 20th century would have made Charles Lightoller give up the sea forever, but he was not a man to let a little thing like having a ship ripped out from under him end his adventures at sea. No, he was not even close to being done with the sea.

Following his survival of the shipwreck of Titanic, Lightoller went on to serve as a commanding officer of the Royal Navy during World War I, Lightoller was given command of his own torpedo boat. He was decorated twice for gallantry for his actions in combat, including sinking the German submarine UB-110. He emerged from the Great War as a full naval Commander. Lightoller retired after the war, but couldn’t leave the sea behind entirely. He and his wife bought their own boat in 1929. They called it Sundower and spent the next decade cruising around northern Europe and carrying out the occasional secret surveillance mission for the Admiralty when the Germans began preparing for war again.

Though Lightoller was retired by the time World War II started, he provided and sailed as a volunteer on one of the “little ships” that played a part in the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation. Rather than allow his motoryacht to be requisitioned by the Admiralty, he and his son Roger and a young Sea Scout named Gerald Ashcroft, crossed the English Channel in Sundowner to assist in the Dunkirk evacuation. The boat was licensed to carry just 21 passengers, but Lightoller and his crew brought back 127 servicemen. On the return journey, Lightoller evaded gunfire from enemy aircraft, using a technique described to him by his youngest son, Herbert, who had joined the RAF and been killed earlier in the war. Gerald Ashcroft later described the incident, “We attracted the attention of a Stuka dive bomber. Commander Lightoller stood up in the bow and I stood alongside the wheelhouse. Commander Lightoller kept his eye on the Stuka till the last second – then he sang out to me “Hard a port!” and I sang out to Roger and we turned very sharply. The bomb landed on our starboard side.” So, years after his first lifesaving event, Lightoller was once again saving lives in an emergency. Many people  would be surprised to learn that he even had a yacht, but the sea was still a part of him. At the time of the evacuation Lightoller’s second son, Trevor was a serving Second Lieutenant with Bernard Montgomery’s 3rd Division, which had retreated towards Dunkirk. Unbeknownst to his dad, Trevor had already been evacuated 48 hours before Sundowner reached Dunkirk.

would be surprised to learn that he even had a yacht, but the sea was still a part of him. At the time of the evacuation Lightoller’s second son, Trevor was a serving Second Lieutenant with Bernard Montgomery’s 3rd Division, which had retreated towards Dunkirk. Unbeknownst to his dad, Trevor had already been evacuated 48 hours before Sundowner reached Dunkirk.

After the Second World War, Lightoller managed a small boatyard in Twickenham, West London, called Richmond Slipways, which built motor launches for the river police. Lightoller died of chronic heart disease on December 8, 1952, aged 78. He was a long-time pipe smoker, and he died during London’s Great Smog of 1952, which took the lives of many elderly people with breathing issues. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered at the Commonwealth “Garden of Remembrance” at Mortlake Crematorium in Richmond, Surrey.