History

Sometimes, the best of intentions can go horribly wrong, and when things go wrong, it becomes a disaster, and disaster is exactly what happened in Centralia, Pennsylvania when a fire was set to burn out an old landfill before the Labor Day holiday in 1962. The fire that was started on May 27, 1962, seemed like a simple solution to a big mess, but the landfill was also an old strip-mine pit, connected to a maze of abandoned underground mining tunnels full of coal. No one knows how the fire got to the coal vein below the ground, but once it did, the situation was out of control. Some called it careless trash incineration in a landfill next to an open pit mine, which ignited a coal vein, but no one expected the fire to crawl insidiously along the rich coal deposits that still laid deep in the ground. No one expected the burning coal to vent hot and poisonous gases up into town, through the basements of homes and businesses. Nevertheless, with dawn came the horror, as residents realized that the fire was not going to be extinguished, or in fact, ever burn itself out…at least not until all the interconnected coal veins in eastern Pennsylvania were finally burned out. As the underground fire worked its way under rows of homes and businesses, the threat of fires, asphyxiation, and carbon monoxide poisoning became a daily concern.

Sometimes, the best of intentions can go horribly wrong, and when things go wrong, it becomes a disaster, and disaster is exactly what happened in Centralia, Pennsylvania when a fire was set to burn out an old landfill before the Labor Day holiday in 1962. The fire that was started on May 27, 1962, seemed like a simple solution to a big mess, but the landfill was also an old strip-mine pit, connected to a maze of abandoned underground mining tunnels full of coal. No one knows how the fire got to the coal vein below the ground, but once it did, the situation was out of control. Some called it careless trash incineration in a landfill next to an open pit mine, which ignited a coal vein, but no one expected the fire to crawl insidiously along the rich coal deposits that still laid deep in the ground. No one expected the burning coal to vent hot and poisonous gases up into town, through the basements of homes and businesses. Nevertheless, with dawn came the horror, as residents realized that the fire was not going to be extinguished, or in fact, ever burn itself out…at least not until all the interconnected coal veins in eastern Pennsylvania were finally burned out. As the underground fire worked its way under rows of homes and businesses, the threat of fires, asphyxiation, and carbon monoxide poisoning became a daily concern.

Probably one of the scariest situations was when a young man, Todd Domboski fell into a hot, steaming hole created by mine fire subsidence. He survived his 45 second ordeal by grabbing onto tree roots, and screaming for help until his cousin ran to his aid, reached into the void, and hoisted him out. Many Centralia residents had worried that a calamity like the one that nearly unfolded that Valentine’s Day in 1981. Four years earlier, Domboski’s father had told a reporter, “I guess some kid will have to get killed by the gas or by falling in one of these steamy holes before anyone will call it an emergency.” Never did he imagine that it would be his kid that would fall through and almost lose his life.

After the near tragedy, signs were posted to warn visitors to the Centralia area about the dangers of death by asphyxiation or being swallowed by the ground, but the old mining town of Centralia, Pennsylvania, was once home to more than 1,000 people. People with no place else to go. Now, it’s nothing more than a smoldering ghost town that’s been burning for over half a century. Though the town was able to extinguish the fire above ground, a much bigger inferno burned underneath, and it eventually spread its way under Centralia’s town center. The fire was so widespread, destructive and unending. It’s thought that there’s enough coal underground to fuel the fire for another 250 years. In 1980, a $42 million relocation plan incentivized most of the townspeople to relocate and most of the homes were demolished, leaving only about a dozen holdouts behind. Today, Centralia exists only as an eerie grid of streets, its driveways disappearing into vacant lots. Remains of a picket fence here, a chair spindle there. Still John Lokitis and 11 others who refused to leave, the

occupants of a dozen scattered structures. Over the decades, the ground has opened up with sulfurous gases sometimes billowing out. The road along Highway 61 swells and cracks open. It is riddled with graffiti and hot to the touch. In the winter, snow melts in patches where the ground is warm. While a few holdouts still live there, I have to wonder what they are thinking. That is like slowly committing suicide, because you refuse to leave the past.

occupants of a dozen scattered structures. Over the decades, the ground has opened up with sulfurous gases sometimes billowing out. The road along Highway 61 swells and cracks open. It is riddled with graffiti and hot to the touch. In the winter, snow melts in patches where the ground is warm. While a few holdouts still live there, I have to wonder what they are thinking. That is like slowly committing suicide, because you refuse to leave the past.

When the United States entered World War I, they sent men into France to join Allied forces there. Their arrival was a great relief to the exhausted Allied soldiers. Before long the American soldiers in France became known as Doughboys. This was not an unknown term, since it had been used For centuries to describe such soldiers as Horatio Nelson’s sailors and Wellington’s soldiers in Spain, for instance. Both of these groups were familiar with fried flour dumplings called doughboys, the predecessor of the modern doughnut that both we and the Doughboys of World War I came to love. The American Doughboys were the men America sent to France in the Great War, who beat Kaiser Bill and fought to make the world safe for Democracy.

When the United States entered World War I, they sent men into France to join Allied forces there. Their arrival was a great relief to the exhausted Allied soldiers. Before long the American soldiers in France became known as Doughboys. This was not an unknown term, since it had been used For centuries to describe such soldiers as Horatio Nelson’s sailors and Wellington’s soldiers in Spain, for instance. Both of these groups were familiar with fried flour dumplings called doughboys, the predecessor of the modern doughnut that both we and the Doughboys of World War I came to love. The American Doughboys were the men America sent to France in the Great War, who beat Kaiser Bill and fought to make the world safe for Democracy.

It is thought, however, that the Doughboys of World War I might have acquired the name in a slightly different way. In fact, there are a variety of theories about the origins of the nickname. One explanation is that the term dates back to the Mexican War of 1846 to 1848, when American infantrymen made long treks over dusty terrain, giving them the appearance of being covered in flour, or dough. As a variation of this account goes, the men were coated in the dust of adobe soil and as a result were called “adobes,” which morphed into “dobies” and, eventually into “doughboys.” Among other theories, according to “War Slang” by Paul Dickson, American journalist and lexicographer H.L. Mencken claimed the nickname could be traced to Continental Army soldiers who kept the piping on their uniforms white through the application of clay. When the troops got rained on the clay on their uniforms turned into “doughy blobs,” supposedly leading to the doughboy moniker.

Whatever the case may be, doughboy was just one of the nicknames given to those who fought in the Great War. For example, “poilu” meaning “hairy one” was a term for a French soldier, as a number of them had beards or mustaches, while a popular slang term for a British soldier was “Tommy,” an abbreviation of Tommy Atkins, a generic name similar to John Doe used in the Unites States on government forms. America’s last

World War I doughboy, Frank Buckles, died in 2011 in West Virginia at age 110. Buckles enlisted in the Army at age 16 in August 1917, four months after the United States entered the conflict, and drove military vehicles in France. One of 4.7 million Americans who served in the war, Buckles was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. It’s strange to think that my grandfather, George Byer was one of the men called doughboys, but then he was stationed in France at that time in history, so I guess that Grandpa was a doughboy.

World War I doughboy, Frank Buckles, died in 2011 in West Virginia at age 110. Buckles enlisted in the Army at age 16 in August 1917, four months after the United States entered the conflict, and drove military vehicles in France. One of 4.7 million Americans who served in the war, Buckles was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. It’s strange to think that my grandfather, George Byer was one of the men called doughboys, but then he was stationed in France at that time in history, so I guess that Grandpa was a doughboy.

Most of the time, when we think of crime and criminals, we think of the worst evil there could be in a person, and I suppose that some criminals have more evil tendencies than others, but once in a while, someone decides to put a bit of a different twist on their crime…intending to romanticize it or give it a Robin Hood feel. In a large part, it is the media that truly romanticizes it or gives it notoriety. If the media didn’t report on every episode of the criminal’s life of crime, perhaps it would not seem so exciting to people, and maybe it wouldn’t inspire other criminals to…go for it. It all seems so exciting, at least that’s how the media plays it up.

Most of the time, when we think of crime and criminals, we think of the worst evil there could be in a person, and I suppose that some criminals have more evil tendencies than others, but once in a while, someone decides to put a bit of a different twist on their crime…intending to romanticize it or give it a Robin Hood feel. In a large part, it is the media that truly romanticizes it or gives it notoriety. If the media didn’t report on every episode of the criminal’s life of crime, perhaps it would not seem so exciting to people, and maybe it wouldn’t inspire other criminals to…go for it. It all seems so exciting, at least that’s how the media plays it up.

In reality, Bonnie and Clyde…notorious robbers and murders lived a very basic existence, and in many ways it was disgusting. Despite common popular culture depictions of Bonnie and Clyde, their life on the run was far from glamorous. They often ate sardines from the can, bathed in rivers, and drove through the night, taking shifts sleeping and driving, all in order to evade capture. They hid out in the forest, hoping not to be seen…always standing guard…always watching. Bonnie Parker met Clyde Barrow in Texas when she was 19 years old. Her husband, whom she married when she was 16, was serving time in jail for murder, and Clyde seemed exciting. Shortly after they met, Barrow was imprisoned for robbery. Bonnie visited Clyde every day, and smuggled a gun into prison to help him escape. He did escape, but was quickly recaptured in Ohio and sent back to jail. When Clyde was paroled in 1932, he immediately hooked up with Bonnie, and the couple began a life of crime together. Apparently Bonnie had a thing for bad boys…to her detriment, in the end.

The pair stole a car and committed several robberies, before Bonnie was caught by police and sent to jail for  two months. Immediately after her release in mid-1932, she hooked up with Clyde again. Over the next two years, the couple teamed with various accomplices to rob a string of banks and stores across five states…Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, New Mexico and Louisiana. To law enforcement agents, the Barrow Gang, including Clyde’s childhood friend, Raymond Hamilton, W.D. Jones, Henry Methvin, Barrow’s brother Buck and his wife Blanche, among others, were cold-blooded criminals who didn’t hesitate to kill anyone who got in their way, especially police or sheriff’s deputies. To the public, however, Bonnie and Clyde’s reputation as dangerous outlaws was mixed with a romantic view of the couple as “Robin Hood”-like folk heroes. Their fame was increased by the fact that Bonnie was a woman, which made her an unlikely criminal, and by the fact that the couple posed for playful photographs together, which were later found by police and released to the media. Police almost captured Bonnie and Clyde in the spring of 1933, with surprise raids on their hideouts in Joplin and Platte City, Missouri. Buck Barrow was killed in the second raid, and Blanche was arrested, but Bonnie and Clyde escaped once again. In January 1934, they attacked the Eastham Prison Farm in Texas to help Hamilton break out of jail, shooting several guards with machine guns…killing one.

two months. Immediately after her release in mid-1932, she hooked up with Clyde again. Over the next two years, the couple teamed with various accomplices to rob a string of banks and stores across five states…Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, New Mexico and Louisiana. To law enforcement agents, the Barrow Gang, including Clyde’s childhood friend, Raymond Hamilton, W.D. Jones, Henry Methvin, Barrow’s brother Buck and his wife Blanche, among others, were cold-blooded criminals who didn’t hesitate to kill anyone who got in their way, especially police or sheriff’s deputies. To the public, however, Bonnie and Clyde’s reputation as dangerous outlaws was mixed with a romantic view of the couple as “Robin Hood”-like folk heroes. Their fame was increased by the fact that Bonnie was a woman, which made her an unlikely criminal, and by the fact that the couple posed for playful photographs together, which were later found by police and released to the media. Police almost captured Bonnie and Clyde in the spring of 1933, with surprise raids on their hideouts in Joplin and Platte City, Missouri. Buck Barrow was killed in the second raid, and Blanche was arrested, but Bonnie and Clyde escaped once again. In January 1934, they attacked the Eastham Prison Farm in Texas to help Hamilton break out of jail, shooting several guards with machine guns…killing one.

Texan prison officials hired Captain Frank Hamer, a retired Texas police officer, as a special investigator to track down Bonnie and Clyde. After a three month search, Hamer traced the couple to Louisiana, where Henry Methvin’s family lived. Bonnie and Clyde appeared, the officers opened fire, killing the couple instantly in a hail of

bullets. All told, the Barrow Gang was believed to have been responsible for the deaths of 13 people, including nine police officers. Bonnie and Clyde are still seen by many as romantic figures, however, especially after the success of the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, starring Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty. It’s really a sad thing when crime is romanticized, because people think of it as an exciting, when in fact, it is a dead end road.

bullets. All told, the Barrow Gang was believed to have been responsible for the deaths of 13 people, including nine police officers. Bonnie and Clyde are still seen by many as romantic figures, however, especially after the success of the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, starring Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty. It’s really a sad thing when crime is romanticized, because people think of it as an exciting, when in fact, it is a dead end road.

As airplanes became an accepted form of transportation, people began to consider traveling further and further. Of course, those first airplanes could never have made the flight across the ocean, but these days planes fly that far with ease. Still, someone had to be brave enough to take that first flight across the ocean. Someone had to trust their plane enough to make the attempt. British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown decided to be the first to make that leap when they made the first non-stop transatlantic flight in June 1919. Their plane was a modified First World War Vickers Vimy bomber. They flew from Saint John’s, Newfoundland to Clifden, Connemara, County Galway, Ireland. Like most accomplishments, the competition was fierce, and there had to be a reward for the winner. The Secretary of State for Air, Winston Churchill, presented them with the Daily Mail prize for the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by airplane in “less than 72 consecutive hours”. A small amount of mail was carried on the flight, making it the first transatlantic airmail flight. The two aviators were awarded the honour of Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire a week later by King George V at Windsor Castle.

As airplanes became an accepted form of transportation, people began to consider traveling further and further. Of course, those first airplanes could never have made the flight across the ocean, but these days planes fly that far with ease. Still, someone had to be brave enough to take that first flight across the ocean. Someone had to trust their plane enough to make the attempt. British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown decided to be the first to make that leap when they made the first non-stop transatlantic flight in June 1919. Their plane was a modified First World War Vickers Vimy bomber. They flew from Saint John’s, Newfoundland to Clifden, Connemara, County Galway, Ireland. Like most accomplishments, the competition was fierce, and there had to be a reward for the winner. The Secretary of State for Air, Winston Churchill, presented them with the Daily Mail prize for the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by airplane in “less than 72 consecutive hours”. A small amount of mail was carried on the flight, making it the first transatlantic airmail flight. The two aviators were awarded the honour of Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire a week later by King George V at Windsor Castle.

As with any record, there is always room for improvement. The first flight took place with two people on board, so on Ma 21, 1927, at age 25, Charles Lindbergh went from being an unknown United States Air Mail pilot, to world fame instantly, by making his Orteig Prize winning nonstop flight from Long Island, New York to Paris. He covered the 33½ hour, 3,600 miles alone in a single-engine Ryan monoplane called the Spirit of Saint Louis.  The plane was build for this flight. This was the first solo transatlantic flight, and the first non-stop flight between North America and mainland Europe. I wonder what he was thinking as he flew for 33½ hours alone over the ocean. He had to keep himself awake, and on course. There was no one else to do it. Most of us have a hard time staying awake for more than 17 or 18 hours, much less 33½ hours. It was an amazing feat, and one for which the fame he gained was well deserved.

The plane was build for this flight. This was the first solo transatlantic flight, and the first non-stop flight between North America and mainland Europe. I wonder what he was thinking as he flew for 33½ hours alone over the ocean. He had to keep himself awake, and on course. There was no one else to do it. Most of us have a hard time staying awake for more than 17 or 18 hours, much less 33½ hours. It was an amazing feat, and one for which the fame he gained was well deserved.

As with any record, someone had to beat it or improve on it or change it in some way. The record held until May 21, 1932, when Amelia Earhart became the first woman to make a solo air crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, from Newfoundland to Ireland. As with Charles Lindbergh, I wondered how Amelia stayed awake for all those hours, and what she was thinking as she flew along…alone for all those hours. I’m sure there was excitement in the extreme, but I’m sure she was weary after the flight was over too.

One of the best ways to form a dictatorship is to suppress knowledge. That’s one reason that propaganda is so important. When the people only hear what the government wants them to, they tend to become compliant…or at least that’s the theory. When Adolf Hitler was elected to office, he was the people’s choice, but they had no idea just how evil he was and how long they would be stuck with him. With the end of democracy, Germany became a one-party dictatorship. The Nazis began a massive propaganda campaign to win the loyalty and cooperation of Germans. The Nazi Propaganda Ministry, directed by Dr Joseph Goebbels, took control of all forms of communication in Germany…newspapers, magazines, books, public meetings, and rallies, art, music, movies, and radio. Viewpoints in any way threatening to Nazi beliefs or to the regime were censored or eliminated from all media. The German people were isolated from the outside world, and while they did not like it, the government became their only source of information.

One of the best ways to form a dictatorship is to suppress knowledge. That’s one reason that propaganda is so important. When the people only hear what the government wants them to, they tend to become compliant…or at least that’s the theory. When Adolf Hitler was elected to office, he was the people’s choice, but they had no idea just how evil he was and how long they would be stuck with him. With the end of democracy, Germany became a one-party dictatorship. The Nazis began a massive propaganda campaign to win the loyalty and cooperation of Germans. The Nazi Propaganda Ministry, directed by Dr Joseph Goebbels, took control of all forms of communication in Germany…newspapers, magazines, books, public meetings, and rallies, art, music, movies, and radio. Viewpoints in any way threatening to Nazi beliefs or to the regime were censored or eliminated from all media. The German people were isolated from the outside world, and while they did not like it, the government became their only source of information.

Germany was now led by a self-educated, high school drop-out named Adolf Hitler, who was by nature strongly anti-intellectual. For Hitler, the reawakening of the long-dormant Germanic spirit, with its racial and militaristic  qualities, was far more important than any traditional notions of learning. Books and writings by such authors as Henri Barbusse, Franz Boas, John Dos Passos, Albert Einstein, Lion Feuchtwanger, Friedrich Förster, Sigmund Freud, John Galsworthy, André Gide, Ernst Glaeser, Maxim Gorki, Werner Hegemann, Ernest Hemingway, Erich Kästner, Helen Keller, Alfred Kerr, Jack London, Emil Ludwig, Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann, Karl Marx, Hugo Preuss, Marcel Proust, Erich Maria Remarque, Walther Rathenau, Margaret Sanger, Arthur Schnitzler, Upton Sinclair, Kurt Tucholsky, Jakob Wassermann, H.G. Wells, Theodor Wolff, Emilé Zola, Arnold Zweig, and Stefan Zweig, were suddenly unGerman. Their books were pulled from libraries and schools. Then, on the night of May 10, 1933, an event unseen in Europe since the Middle Ages occurred as German students from universities once regarded as among the finest in the world, gathered in Berlin to burn books with unGerman ideas. It was the Nazi burning of knowledge. Students can be very impressionable, and easily lead, and these students played right into Hitler’s hand.

qualities, was far more important than any traditional notions of learning. Books and writings by such authors as Henri Barbusse, Franz Boas, John Dos Passos, Albert Einstein, Lion Feuchtwanger, Friedrich Förster, Sigmund Freud, John Galsworthy, André Gide, Ernst Glaeser, Maxim Gorki, Werner Hegemann, Ernest Hemingway, Erich Kästner, Helen Keller, Alfred Kerr, Jack London, Emil Ludwig, Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann, Karl Marx, Hugo Preuss, Marcel Proust, Erich Maria Remarque, Walther Rathenau, Margaret Sanger, Arthur Schnitzler, Upton Sinclair, Kurt Tucholsky, Jakob Wassermann, H.G. Wells, Theodor Wolff, Emilé Zola, Arnold Zweig, and Stefan Zweig, were suddenly unGerman. Their books were pulled from libraries and schools. Then, on the night of May 10, 1933, an event unseen in Europe since the Middle Ages occurred as German students from universities once regarded as among the finest in the world, gathered in Berlin to burn books with unGerman ideas. It was the Nazi burning of knowledge. Students can be very impressionable, and easily lead, and these students played right into Hitler’s hand.

The youth-oriented Nazi movement had always attracted a sizable following among university students. Even back in the 1920s they thought Nazism was the wave of the future. They joined the National Socialist  German Students’ League, put on swastika armbands and harassed anti-Nazi teachers. Many formerly reluctant professors were swept along by the outpouring of student enthusiasm that followed Hitler’s seizure of power. Most of the professors eagerly surrendered their intellectual honesty and took the required Nazi oath of allegiance. They also wanted to curry favor with Nazi Party officials in order to grab one of the academic vacancies resulting from the mass expulsion of Jewish professors and deans. The entire education system of a nation changed…almost overnight. As the German-Jewish poet, Heinrich Heine, had declared, a hundred years before the advent of Hitler, “Wherever books are burned, human beings are destined to be burned too.” And so it was in the end.

German Students’ League, put on swastika armbands and harassed anti-Nazi teachers. Many formerly reluctant professors were swept along by the outpouring of student enthusiasm that followed Hitler’s seizure of power. Most of the professors eagerly surrendered their intellectual honesty and took the required Nazi oath of allegiance. They also wanted to curry favor with Nazi Party officials in order to grab one of the academic vacancies resulting from the mass expulsion of Jewish professors and deans. The entire education system of a nation changed…almost overnight. As the German-Jewish poet, Heinrich Heine, had declared, a hundred years before the advent of Hitler, “Wherever books are burned, human beings are destined to be burned too.” And so it was in the end.

When a volcano erupts, we think of lava and billowing clouds of ash. Those things do happen, but what we don’t think about is what can happen to planes, because of the ash. I suppose that is because we think of that eruption as being a very localized thing. In reality, it isn’t, because the jet stream moves the air around our world, and the ash goes with it. Volcanic ash and airplane engines are not a good mix. Volcanic ash consists of small tephra, which are bits of pulverized rock and glass less than 2 millimeters in diameter created by volcanic eruptions. As the ash enters the atmosphere, it is carried away from the volcano by winds. The ash with the smallest size can remain in the atmosphere for a considerable period of time. The ash cloud can be dangerous to aviation if it reaches the heights of aircraft flight paths.

When a volcano erupts, we think of lava and billowing clouds of ash. Those things do happen, but what we don’t think about is what can happen to planes, because of the ash. I suppose that is because we think of that eruption as being a very localized thing. In reality, it isn’t, because the jet stream moves the air around our world, and the ash goes with it. Volcanic ash and airplane engines are not a good mix. Volcanic ash consists of small tephra, which are bits of pulverized rock and glass less than 2 millimeters in diameter created by volcanic eruptions. As the ash enters the atmosphere, it is carried away from the volcano by winds. The ash with the smallest size can remain in the atmosphere for a considerable period of time. The ash cloud can be dangerous to aviation if it reaches the heights of aircraft flight paths.

Part of the problem is that pilots can’t see ash clouds at night, and ash particles are too small to return an echo to on-board weather radars on commercial airliners. Even when they are flying in daylight, pilots may interpret a visible ash cloud as a normal cloud of water vapor and not a danger…especially if the ash has travelled far from the eruption site. Volcanic ash has a melting point of approximately 2,010° F, which is below the operating temperature of modern commercial jet engines, about 2,550° F. Volcanic ash can damage gas turbines in a number of ways. These can be categorized into those that pose an immediate hazard to the engines and those that present a maintenance problem. As was the case with KLM Flight 867, bound for Anchorage, Alaska, when all four engines flamed out after the aircraft inadvertently entered a cloud of ash blown from erupting Redoubt Volcano, 150 miles away. The volcano had begun erupting 10 hours earlier on that morning of December 15, 1989. Only after the crippled jet had dropped from an altitude of 27,900 feet to 13,300 feet…a fall of more than 2 miles…was the crew able to restart all engines and land the plane safely at Anchorage. The plane required $80 million in repairs, including the replacement of all four damaged engines.

The 2010 eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland, were relatively small for volcanic eruptions. Nevertheless, they caused enormous disruption to air travel across western and northern Europe over the next six days. Additional localized disruption occurred into May 2010. The eruption was declared officially over in October 2010. About 20 countries closed their airspace to commercial jet traffic and it affected about 10 million travelers. This was the highest level of air travel disruption since World War II. It’s strange for us to think that so much can happen to a jet engine is volcanic ash is introduced into it, but that is definitely the case, and if air planes travel in the area of certain types of volcanic ash, planes can be lost. The only prudent thing to do is stop travel in the area…no matter how inconvenient it is to travelers.

The 2010 eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland, were relatively small for volcanic eruptions. Nevertheless, they caused enormous disruption to air travel across western and northern Europe over the next six days. Additional localized disruption occurred into May 2010. The eruption was declared officially over in October 2010. About 20 countries closed their airspace to commercial jet traffic and it affected about 10 million travelers. This was the highest level of air travel disruption since World War II. It’s strange for us to think that so much can happen to a jet engine is volcanic ash is introduced into it, but that is definitely the case, and if air planes travel in the area of certain types of volcanic ash, planes can be lost. The only prudent thing to do is stop travel in the area…no matter how inconvenient it is to travelers.

During World War I, the Germans had taken a hard line concerning the waters around England. It was called unrestricted submarine warfare, and it meant that German submarines would attack any ship found in the war zone, which, in this case, was the area around the British Isles…no matter what kind of ship it was, and even if it was from a neutral country. Of course, this was not going to fly, and since Germany was afraid of the United States, they finally agreed to only go after military ships. Nevertheless, mistakes can be made, and that is what happened on May 7, 1915, when a German U-boat torpedoed and sank the RMS Lusitania, a British ocean liner en route from New York to Liverpool, England. Of the more than 1,900 passengers and crew members on board, more than 1,100 perished, including more than 120 Americans. A warning had been placed in several New York newspapers in early May 1915, by the German Embassy in Washington, DC, stating that Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones did so at their own risk. The announcement was placed on the same page as an advertisement of the imminent sailing of the Lusitania liner from New York back to Liverpool. Still this did not stop the sailing of the Lusitania, because the captain of the Lusitania ignored the British Admiralty’s recommendations, and at 2:12 pm on May 7 the 32,000-ton ship was hit by an exploding torpedo on its starboard side. The torpedo blast was followed by a larger explosion, probably of the ship’s boilers, and the ship sank off the south coast of Ireland in less than 20 minutes.

During World War I, the Germans had taken a hard line concerning the waters around England. It was called unrestricted submarine warfare, and it meant that German submarines would attack any ship found in the war zone, which, in this case, was the area around the British Isles…no matter what kind of ship it was, and even if it was from a neutral country. Of course, this was not going to fly, and since Germany was afraid of the United States, they finally agreed to only go after military ships. Nevertheless, mistakes can be made, and that is what happened on May 7, 1915, when a German U-boat torpedoed and sank the RMS Lusitania, a British ocean liner en route from New York to Liverpool, England. Of the more than 1,900 passengers and crew members on board, more than 1,100 perished, including more than 120 Americans. A warning had been placed in several New York newspapers in early May 1915, by the German Embassy in Washington, DC, stating that Americans traveling on British or Allied ships in war zones did so at their own risk. The announcement was placed on the same page as an advertisement of the imminent sailing of the Lusitania liner from New York back to Liverpool. Still this did not stop the sailing of the Lusitania, because the captain of the Lusitania ignored the British Admiralty’s recommendations, and at 2:12 pm on May 7 the 32,000-ton ship was hit by an exploding torpedo on its starboard side. The torpedo blast was followed by a larger explosion, probably of the ship’s boilers, and the ship sank off the south coast of Ireland in less than 20 minutes.

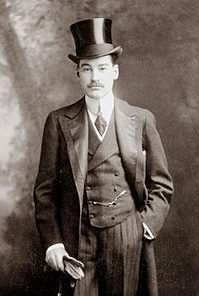

While the sinking of the Lusitania was a horrible tragedy, there were heroics too. One such hero was Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, Sr. Vanderbilt was an extremely wealthy American businessman and sportsman, and a member of the famous Vanderbilt family, but on this trip, he was so much more than that. On May 1, 1915, Alfred Vanderbilt boarded the RMS Lusitania bound for Liverpool as a first class passenger. Vanderbilt was on a business trip. He was traveling with only his valet, Ronald Denyer. His family stayed at home in New York. On May 7, off the coast of County Cork, Ireland, German U-boat, U-20 torpedoed the ship, triggering a secondary explosion that sank the giant ocean liner within 18 minutes. Vanderbilt and Denyer immediately went into action, helping others into lifeboats, and then Vanderbilt gave his lifejacket to save a female passenger. Vanderbilt had promised the young mother of a small baby that he would locate an extra life vest for her. Failing to do so, he offered her his own life vest, which he proceeded to tie on to her himself, because she was holding her infant child in her arms at the time.

Vanderbilt had to know he was sealing his own fate, since he could not swim and he knew there were no other life vests or lifeboats available. They were in waters where no outside help was likely to be coming. Still, he  gave his life for hers and that of her child. Because of his fame, several people on the Lusitania who survived the tragedy were observing him while events unfolded at the time, and so they took note of his actions. I suppose that had he not been famous, people would not have known who he was to tell the story. Vanderbilt and Denyer were among the 1198 passengers who did not survive the incident. His body was never recovered. Probably the most ironic fact is that three years earlier Vanderbilt had made a last-minute decision not to return to the US on RMS Titanic. In fact, his decision not to travel was made so late that some newspaper accounts listed him as a casualty after that sinking too. He would not be so fortunate when he chose to travel on Lusitania.

gave his life for hers and that of her child. Because of his fame, several people on the Lusitania who survived the tragedy were observing him while events unfolded at the time, and so they took note of his actions. I suppose that had he not been famous, people would not have known who he was to tell the story. Vanderbilt and Denyer were among the 1198 passengers who did not survive the incident. His body was never recovered. Probably the most ironic fact is that three years earlier Vanderbilt had made a last-minute decision not to return to the US on RMS Titanic. In fact, his decision not to travel was made so late that some newspaper accounts listed him as a casualty after that sinking too. He would not be so fortunate when he chose to travel on Lusitania.

War is tough enough without having a traitor in the mix, and when a traitor is involved, things get even worse. One such traitor of World War II, was Mildred Gillars, aka Axis Sally. Apparently, Gillars, an American, was a opportunist. In 1940, she went to work as an announcer with the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft (RRG), German State Radio. At the time, I suppose that she did nothing wrong…up to that point. In 1941, the US State Department was advising American nationals to return home, but Gillars chose to remain because her fiancé, Paul Karlson, a naturalized German citizen, said he would never marry her if she returned to the United States. Then, Karlson was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was killed in action. Gillars still did not return home.

War is tough enough without having a traitor in the mix, and when a traitor is involved, things get even worse. One such traitor of World War II, was Mildred Gillars, aka Axis Sally. Apparently, Gillars, an American, was a opportunist. In 1940, she went to work as an announcer with the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft (RRG), German State Radio. At the time, I suppose that she did nothing wrong…up to that point. In 1941, the US State Department was advising American nationals to return home, but Gillars chose to remain because her fiancé, Paul Karlson, a naturalized German citizen, said he would never marry her if she returned to the United States. Then, Karlson was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was killed in action. Gillars still did not return home.

On December 7, 1941, Gillars was working in the studio when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was announced. She broke down in front of her colleagues and denounced their allies in the east. “I told them what I thought about Japan and that the Germans would soon find out about them,” she recalled. “The shock was terrific. I lost all discretion.” This may have been the the last time she had any self respect. She later said that she knew that her outburst could send her to a concentration camp, so faced with the prospect of joblessness or prison, the frightened Gillars produced a written oath of allegiance to Germany and returned to work. She sold out. Her duties were initially limited to announcing records and participating in chat shows, but treason is a slippery slope. Gillars’ broadcasts initially were largely apolitical, but that changed in 1942, when Max Otto Koischwitz, the program director in the USA Zone at the RRG, cast Gillars in a new show called Home Sweet Home. She soon acquired several names amongst her GI audience, including the Berlin Bitch, Berlin Babe, Olga, and Sally, but the one most common was “Axis Sally”. This name probably came when asked on air to describe herself, Gillars had said she was “the Irish type… a real Sally.”

As her broadcasts progressed, Gillars began doing a show called Home Sweet Home Hour. This show ran from December 24, 1942, until 1945. It was a regular propaganda program, the purpose of which was to make US forces in Europe feel homesick. A running theme of these broadcasts was the infidelity of soldiers’ wives and sweethearts while the listeners were stationed in Europe and North Africa. I’m was designed to promote depression. I guess her aversion to the ways of the Japanese and Germans wasn’t so strong after all. She also did a show called Midge-at-the-Mike, which broadcast from March to late fall 1943. I this program, she played American songs interspersed with defeatist propaganda, anti-Semitic rhetoric and attacks on Franklin D. Roosevelt. And she did the GI’s Letter-box and Medical Reports 1944, which was directed at the US home audience. In this show, Gillars used information on wounded and captured US airmen to cause fear and worry in their families. After D-Day, June 6, 1944, US soldiers wounded and captured in France were also reported on. Gillars and Koischwitz worked for a time from Chartres and Paris for this purpose, visiting hospitals and interviewing POWs. In 1943 they had toured POW camps in Germany, interviewing captured Americans and recording their messages for their families in the US. The interviews were then edited for broadcast as though the speakers were well-treated or sympathetic to the Nazi cause. Gillars made her most notorious broadcast on June 5, 1944, just prior to the D-Day invasion of Normandy, France, in a radio play written by Koischwitz, Vision Of Invasion. She played Evelyn, an Ohio mother, who dreams that her son had died a horrific death on a ship in the English Channel during an attempted invasion of Occupied Europe.

After the war, Gillars mingled with the people of Germany, until her capture. Gillars was indicted on September 10, 1948, and charged with ten counts of treason, but only eight were proceeded with at her trial, which began  on January 25, 1949. The prosecution relied on the large number of her programs recorded by the FCC, stationed in Silver Hill, Maryland, to show her active participation in propaganda activities against the United States. It was also shown that she had taken an oath of allegiance to Hitler. The defense argued that her broadcasts stated unpopular opinions but did not amount to treasonable conduct. It was also argued that she was under the hypnotic influence of Koischwitz and therefore not fully responsible for her actions until after his death. On March 10, 1949, the jury convicted Gillars on just one count of treason, that of making the Vision Of Invasion broadcast. She was sentenced to 10 to 30 years in prison, and a $10,000 fine. In 1950, a federal appeals court upheld the sentence. She died June 25, 1988 at the age of 87.

on January 25, 1949. The prosecution relied on the large number of her programs recorded by the FCC, stationed in Silver Hill, Maryland, to show her active participation in propaganda activities against the United States. It was also shown that she had taken an oath of allegiance to Hitler. The defense argued that her broadcasts stated unpopular opinions but did not amount to treasonable conduct. It was also argued that she was under the hypnotic influence of Koischwitz and therefore not fully responsible for her actions until after his death. On March 10, 1949, the jury convicted Gillars on just one count of treason, that of making the Vision Of Invasion broadcast. She was sentenced to 10 to 30 years in prison, and a $10,000 fine. In 1950, a federal appeals court upheld the sentence. She died June 25, 1988 at the age of 87.

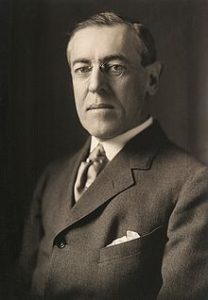

While Germany was willing to go to war, they had, nevertheless, a healthy fear of the United States. During World War I, Germany introduced unrestricted submarine warfare. It was early 1915, and Germany decided that the area around the British Isles was a war zone, and all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, would be attacked by the German navy. That action set in motion a series of attacks on merchant ships, that finally led to the sinking of the British passenger ship, RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. It was at this point that President Woodrow Wilson decided that it was time to pressure the German government to curb their naval actions. Because the German government didn’t want to antagonize the United States, they agreed to put restrictions on the submarine policy going forward, which angered many of their naval leaders, including the naval commander in chief, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who showed his frustration by resigning in March 1916.

While Germany was willing to go to war, they had, nevertheless, a healthy fear of the United States. During World War I, Germany introduced unrestricted submarine warfare. It was early 1915, and Germany decided that the area around the British Isles was a war zone, and all merchant ships, including those from neutral countries, would be attacked by the German navy. That action set in motion a series of attacks on merchant ships, that finally led to the sinking of the British passenger ship, RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. It was at this point that President Woodrow Wilson decided that it was time to pressure the German government to curb their naval actions. Because the German government didn’t want to antagonize the United States, they agreed to put restrictions on the submarine policy going forward, which angered many of their naval leaders, including the naval commander in chief, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who showed his frustration by resigning in March 1916.

On March 24, 1916, soon after Tirpitz’s resignation, a German U-boat submarine attacked the French passenger steamer Sussex, in the English Channel, thinking it was a British ship equipped to lay explosive mines. It was apparently an honest mistake, and the ship did not sink. Still, 50 people were killed and many  more injured, including several Americans. On April 19, in an address to the United States Congress, President Wilson took a firm stance, stating that unless the Imperial German Government agreed to immediately abandon its present methods of warfare against passenger and freight carrying vessels the United States would have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the Government of the German Empire altogether.

more injured, including several Americans. On April 19, in an address to the United States Congress, President Wilson took a firm stance, stating that unless the Imperial German Government agreed to immediately abandon its present methods of warfare against passenger and freight carrying vessels the United States would have no choice but to sever diplomatic relations with the Government of the German Empire altogether.

After Wilson’s speech, the US ambassador to Germany, James W. Gerard, spoke directly to Kaiser Wilhelm on May 1 at the German army headquarters at Charleville in eastern France. After Gerard protested the continued German submarine attacks on merchant ships, the Kaiser in turn denounced the American government’s compliance with the Allied naval blockade of Germany, in place since late 1914. Nevertheless, Germany could not risk American entry into the war against them, so when Gerard urged the Kaiser to provide assurances of a change in the submarine policy, the Kaiser agreed.

On May 6, the German government signed the so-called Sussex Pledge, promising to stop the indiscriminate sinking of non-military ships. According to the pledge, merchant ships would be searched, and sunk only if they  were found to be carrying contraband materials. Furthermore, no ship would be sunk before safe passage had been provided for the ship’s crew and its passengers. Gerard was skeptical of the intentions of the Germans, and wrote in a letter to the United States State Department that “German leaders, forced by public opinion, and by the von Tirpitz and Conservative parties would take up ruthless submarine warfare again, possibly in the autumn, but at any rate about February or March, 1917.” Gerard was right, and on February 1, 1917, Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Two days later, Wilson announced a break in diplomatic relations with the German government, and on April 6, 1917, the United States formally entered World War I on the side of the Allies.

were found to be carrying contraband materials. Furthermore, no ship would be sunk before safe passage had been provided for the ship’s crew and its passengers. Gerard was skeptical of the intentions of the Germans, and wrote in a letter to the United States State Department that “German leaders, forced by public opinion, and by the von Tirpitz and Conservative parties would take up ruthless submarine warfare again, possibly in the autumn, but at any rate about February or March, 1917.” Gerard was right, and on February 1, 1917, Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Two days later, Wilson announced a break in diplomatic relations with the German government, and on April 6, 1917, the United States formally entered World War I on the side of the Allies.

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

Desperate times call for desperate measures…and sometimes, they call for pleading. On March 23, 1918, two days after the launch of a major German offensive in northern France, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George telegraphed the British ambassador in Washington, Lord Reading, urging him to explain to United States President Woodrow Wilson that without help from the US, “we cannot keep our divisions supplied for more than a short time at the present rate of loss. This situation is undoubtedly critical and if America delays now she may be too late.” Of course, nothing happens quickly in government, but this was a different thing. In response, President Wilson agreed to send a direct order to the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing, telling him that American troops already in France should join British and French divisions immediately, without waiting for enough soldiers to arrive to form brigades of their own. Pershing agreed to this on April 2, providing a boost in morale for the exhausted Allies.

The non-stop German offensive continued to take its toll throughout the month of April, however, because the majority of American troops in Europe, who were now arriving at a rate of 120,000 a month, were still not sent into battle. In a meeting of the Supreme War Council of Allied leaders at Abbeville, near the coast of the English Channel, which began on May 1, 1918, Clemenceau, Lloyd George and General Ferdinand Foch, the recently named Generalissimo of all Allied forces on the Western Front, was trying hard to persuade Pershing to send all the existing American troops to the front at once. Pershing resisted, reminding the group that the United States had entered the war “independently” of the other Allies, and indeed, the United States would insist during and after the war on being known as an “associate” rather than a full-fledged ally. He further stated, “I do not suppose that the American army is to be entirely at the disposal of the French and British commands.” I’m sure his remarks brought with them, much concern.

On May 2, the second day of the meeting, the debate continued, with Pershing holding his ground in the face of  heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.

heated appeals by the other leaders. He proposed a compromise, which in the end Lloyd George and Clemenceau had no choice but to accept. Pershing proposed that the United States would send the 130,000 troops arriving in May, as well as another 150,000 in June, to join the Allied front line. He would not make provision for July. This agreement meant that of the 650,000 American troops in Europe by the end of May 1918, roughly one third would go to battle that summer. The other two thirds would not go to the front until they were organized, trained and ready to fight as a purely American army, which Pershing estimated would not happen until the late spring of 1919. I’m sure Pershing’s concern was poorly trained soldiers fighting with little chance of winning. Still, by the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million American soldiers had served on the battlefields of Western Europe, and some 50,000 of them had lost their lives. The United States did go into battle and help win that war, but many thought that the delays cost lives.