History

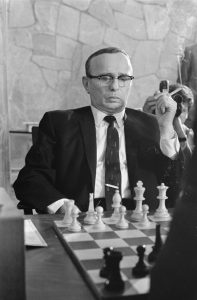

Mastery knows no age. Genius can occur in anyone, and of course, always presents itself when a child is very young. In 1920, one such genius, Samuel Reshevsky was busy mastering chess masters in France. Reshevsky learned chess when he was just 4 years old. He became known as a child chess prodigy and was playing simultaneous games of chess against adults when he was 6 years of age. At age 8 he was playing chess against strong players. Following the events of World War 1, Reshevsky immigrated to the United States. As a 9 year old, his first American simultaneous exhibition was with 20 officers and cadets at the Military Academy at West Point. He won 19 games and drew one. He toured the country and played over 1,500 games as a 9 year old in simultaneous exhibitions and only lost 8 games. In his early years he did not go to school and his parents ended up in Manhattan Children’s Court on charges of improper guardianship. In reality, little Samuel probably could have taught the teachers, so missing some of his education was not detrimental to him in any way.

Mastery knows no age. Genius can occur in anyone, and of course, always presents itself when a child is very young. In 1920, one such genius, Samuel Reshevsky was busy mastering chess masters in France. Reshevsky learned chess when he was just 4 years old. He became known as a child chess prodigy and was playing simultaneous games of chess against adults when he was 6 years of age. At age 8 he was playing chess against strong players. Following the events of World War 1, Reshevsky immigrated to the United States. As a 9 year old, his first American simultaneous exhibition was with 20 officers and cadets at the Military Academy at West Point. He won 19 games and drew one. He toured the country and played over 1,500 games as a 9 year old in simultaneous exhibitions and only lost 8 games. In his early years he did not go to school and his parents ended up in Manhattan Children’s Court on charges of improper guardianship. In reality, little Samuel probably could have taught the teachers, so missing some of his education was not detrimental to him in any way.

Reshevsky was a tough and forceful player who was superb at positional play, but could also play brilliant  tactical chess when warranted. He often used huge amounts of time in the opening, a dangerous tactic which sometimes forced him to play the rest of the game in a very short amount of time. That sometimes unsettled Reshevsky’s opponents, but at other times resulted in blunders on his part. Reshevsky’s inadequate study of the opening and his related tendency to fall into time-pressure may have been the reasons that, despite his great talent, he never became world champion; he himself acknowledged this in his book on chess upsets.

tactical chess when warranted. He often used huge amounts of time in the opening, a dangerous tactic which sometimes forced him to play the rest of the game in a very short amount of time. That sometimes unsettled Reshevsky’s opponents, but at other times resulted in blunders on his part. Reshevsky’s inadequate study of the opening and his related tendency to fall into time-pressure may have been the reasons that, despite his great talent, he never became world champion; he himself acknowledged this in his book on chess upsets.

Reshevsky never became a truly professional chess player. He gave up competitive chess for seven years, from 1924 to 1931, to complete his secondary education. He graduated from the University of Chicago in 1934 with a degree in accounting, and supported himself and his family by working as an accountant. Not everyone could leave off and then pick up their education and never miss a beat. Of course, when you have genius level intelligence, I guess that isn’t a problem.

During the Vietnam War, as in any war, children can become displaced because of the loss of their parents. The country has already lost so many people, and often there is no one to take these little orphans, so they often end up in an orphanage, waiting for someone to come along and adopt them. Many times, they live their entire childhood in that orphanage. For a country that has already be devastated by war, the cost of raising these children is detrimental. Such was the case for orphaned children from the Vietnam War. Then the United States made the decision to airlift these children to the United States to be adopted by American families who were waiting for children. The plan was dubbed Operation Baby Lift, and while it would end up being successful, it got of the a sad and rocky start on April 4, 1975, when the first plane crashed shortly after taking off from Tan Son Nhut airbase in Saigon. On board were more than 300 passengers. Of those, 138 passengers, mostly children were killed.

During the Vietnam War, as in any war, children can become displaced because of the loss of their parents. The country has already lost so many people, and often there is no one to take these little orphans, so they often end up in an orphanage, waiting for someone to come along and adopt them. Many times, they live their entire childhood in that orphanage. For a country that has already be devastated by war, the cost of raising these children is detrimental. Such was the case for orphaned children from the Vietnam War. Then the United States made the decision to airlift these children to the United States to be adopted by American families who were waiting for children. The plan was dubbed Operation Baby Lift, and while it would end up being successful, it got of the a sad and rocky start on April 4, 1975, when the first plane crashed shortly after taking off from Tan Son Nhut airbase in Saigon. On board were more than 300 passengers. Of those, 138 passengers, mostly children were killed.

Captain Dennis “Bud” Traynor was the captain on the plane. Many of the 138 passengers were children, and  many of them were under age 2 and so small, they had to be carried onto the plane. “We bucket-brigade-loaded the children right up the stairs into the airplane,” Traynor remembers. The flight began normally, but shortly into the flight, when the plane’s cargo doors malfunctioned they blew out, taking with them a chunk of the tail. There was a rapid decompression inside the aircraft, causing the pilot, Traynor, to crash land the C-5 cargo plane into a nearby rice paddy. Traynor managed to stabilize the plane and turn it back toward Vietnam. After that, his only option was a crash landing. The impact was fierce. “It cut all control cables to the tail,” explains Traynor. “So I’m pulling and pulling and pulling, and my nose is going down further and further and we’re going faster and faster and faster, and I can’t figure this out. We came to a stop and I thought to myself ‘I’m alive,'” he says. “And so I undid my lap belt, fell to the ceiling, rolled open the side window, and stepped out and saw the wings burning. And I thought, ‘Oh no, that’s the rest of the airplane.'” Out of the more than 300 people on board, the death toll included 78 children and about 50 adults, including Air Force personnel. More than 170 survived.

many of them were under age 2 and so small, they had to be carried onto the plane. “We bucket-brigade-loaded the children right up the stairs into the airplane,” Traynor remembers. The flight began normally, but shortly into the flight, when the plane’s cargo doors malfunctioned they blew out, taking with them a chunk of the tail. There was a rapid decompression inside the aircraft, causing the pilot, Traynor, to crash land the C-5 cargo plane into a nearby rice paddy. Traynor managed to stabilize the plane and turn it back toward Vietnam. After that, his only option was a crash landing. The impact was fierce. “It cut all control cables to the tail,” explains Traynor. “So I’m pulling and pulling and pulling, and my nose is going down further and further and we’re going faster and faster and faster, and I can’t figure this out. We came to a stop and I thought to myself ‘I’m alive,'” he says. “And so I undid my lap belt, fell to the ceiling, rolled open the side window, and stepped out and saw the wings burning. And I thought, ‘Oh no, that’s the rest of the airplane.'” Out of the more than 300 people on board, the death toll included 78 children and about 50 adults, including Air Force personnel. More than 170 survived.

While it was an unusual plan, hatched in the midst of the political fallout, the United States government announced the plan to get thousands of displaced Vietnamese children out of the country. President Ford directed that money from a special foreign aid children’s fund be made available to fly 2,000 South Vietnamese orphans to the United States. Operation Baby Lift lasted for just ten days. Baby Lift was carried out during the final, desperate phase of the war, as North Vietnamese forces closed in on Saigon. Although this first flight ended in tragedy, the rest of the flights were completed safely, and Baby Lift aircraft brought orphans across the Pacific until the mission’s conclusion on April 14, just 16 days before the fall of Saigon and the end of the war.

While it was an unusual plan, hatched in the midst of the political fallout, the United States government announced the plan to get thousands of displaced Vietnamese children out of the country. President Ford directed that money from a special foreign aid children’s fund be made available to fly 2,000 South Vietnamese orphans to the United States. Operation Baby Lift lasted for just ten days. Baby Lift was carried out during the final, desperate phase of the war, as North Vietnamese forces closed in on Saigon. Although this first flight ended in tragedy, the rest of the flights were completed safely, and Baby Lift aircraft brought orphans across the Pacific until the mission’s conclusion on April 14, just 16 days before the fall of Saigon and the end of the war.

When the United States, still known as the colonies at that time, it lacked sufficient funds to build a strong navy, and with the coming Revolutionary War, they needed that strength. So, the Continental Congress gave privateers permission to attack any and all British ships. What is a privateer, you might ask? A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war.

When the United States, still known as the colonies at that time, it lacked sufficient funds to build a strong navy, and with the coming Revolutionary War, they needed that strength. So, the Continental Congress gave privateers permission to attack any and all British ships. What is a privateer, you might ask? A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war.

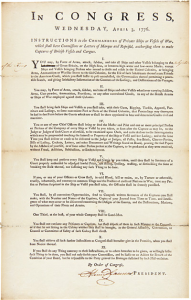

In a bill signed by John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, and dated April 3, 1776, the Continental Congress issued, “INSTRUCTIONS to the COMMANDERS of Private Ships or vessels of War, which shall have Commissions of Letters of Marque and Reprisal, authorizing them to make Captures of British Vessels and Cargoes.” Letters of Marque and Reprisal were the official documents by which 18th century governments commissioned private commercial ships, known as privateers, to act on their behalf, attacking ships carrying the flags of enemy nations. As a perk, any goods captured by the privateer were divided between the ship’s owner and the government that had issued the letter.

Congress informed American privateers on this day that, “YOU may, by Force of Arms, attack, subdue, and take all Ships and other Vessels belonging to the Inhabitants of Great Britain, on the high seas, or between high-water and low-water Marks, except Ships and Vessels bringing Persons who intend to settle and reside in the United Colonies, or bringing Arms, Ammunition or Warlike Stores to the said Colonies, for the Use of such Inhabitants thereof as are Friends to the American Cause, which you shall suffer to pass unmolested, the Commanders thereof permitting a peaceable Search, and giving satisfactory Information of the Contents of the Ladings, and Destinations of the Voyages.” In many ways, this action was very similar to guerrilla warfare, except it was a battle fought on the high seas, and unlike guerrillas, these men were acting under the authority of the government…even if both were fighting for their nation.

For those who faced them on the high seas, there was no difference between pirates and privateers. They  acted and operated identically, boarding and capturing ships using force, if necessary. However, privateers holding Letters of Marque were not subject to prosecution by their home nation and, if captured, were treated as prisoners of war instead of criminals by foreign nations. I wonder if their were actually pirates among he privateers. To me, it would make sense to believe that their were, but perhaps the government would not authorize known pirates to do this work. Either way, the privateer commission was a very successful form of warfare in the Revolutionary War days.

acted and operated identically, boarding and capturing ships using force, if necessary. However, privateers holding Letters of Marque were not subject to prosecution by their home nation and, if captured, were treated as prisoners of war instead of criminals by foreign nations. I wonder if their were actually pirates among he privateers. To me, it would make sense to believe that their were, but perhaps the government would not authorize known pirates to do this work. Either way, the privateer commission was a very successful form of warfare in the Revolutionary War days.

When we think of diving suits, most of us think of the modern day neoprene wet suit, but the diving suits of the past were very different. Of course, the suits that allow divers to go deeper are much different that the more shallow-diving wet suit, but they are still vastly different that the original types of deep-diving suits that were used earlier. One of those earlier suits…the suit designed by Chester E. Macduffee looks like something out of an old movie. In fact, it reminds me of the robot on the 1965 Lost in Space series. Macduffee was an obscure inventor, who patented 4 inventions, and then disappeared from public view. There is very little information out there about him. Nevertheless, I find his 250 Kilo diving suit to be very interesting.

When we think of diving suits, most of us think of the modern day neoprene wet suit, but the diving suits of the past were very different. Of course, the suits that allow divers to go deeper are much different that the more shallow-diving wet suit, but they are still vastly different that the original types of deep-diving suits that were used earlier. One of those earlier suits…the suit designed by Chester E. Macduffee looks like something out of an old movie. In fact, it reminds me of the robot on the 1965 Lost in Space series. Macduffee was an obscure inventor, who patented 4 inventions, and then disappeared from public view. There is very little information out there about him. Nevertheless, I find his 250 Kilo diving suit to be very interesting.

Macduffee’s Armored Diving Suit was tested in 1915 in Long Island Sound. It was made from aluminum alloy and weighed about 250 kilo, which is 551 pounds. The cylindrical joints were mounted on ball bearings to allow movement, but in one direction only. They were not watertight, so Macduffee put a waterpump into the suit. This pump was able to pump water from the leg section into the sea. The pump operated on compressed air supplied from the surface. The used air from the pump then expanded into the suit and was used by the diver for breathing. The pump was driven by electricity…another factor that would make me nervous. The idea of mixing water and electricity to that degree would make me extremely nervous. The suit was equipped with a 12 section-gripper mounted on  one arm and a electric light on the other arm. as well as a hook on one arm. Macduffee’s suit reached 65 meters, or 213 feet, of waterdepth in 1915! Pretty amazing distance for that era. The current diving suits reach distances of about 2,000 feet, making the Macduffee suit a shallow water suit, in reality.

one arm and a electric light on the other arm. as well as a hook on one arm. Macduffee’s suit reached 65 meters, or 213 feet, of waterdepth in 1915! Pretty amazing distance for that era. The current diving suits reach distances of about 2,000 feet, making the Macduffee suit a shallow water suit, in reality.

The diver got in the suit, and then the suit was lowered down by way of a cable. I wonder what the first diver thought of all that. Testing the suit must have been a little bit scary, because of course, they didn’t fully know how the suit would do in the deep water. I’m sure it occurred to them that they could be crushed. One thing is for sure, if a shark bit him, I think the shark would be the one who was surprised, especially when some of their teeth came out. Modern-day deep diving suits don’t look all that different when you think about it, but they are much easier to use.

Over the course of our nation’s history, we have managed to keep most of our presidents safe. Out of 45 Presidents of the United States, 4 were assassinated, and 6 others were shot while in office, but survived their attacks. Ronald Regan was the last United States President to be shot while in office. Reagan did not immediately realize that he had been shot…something that came as a shock to many. He was rushed to the hospital, where he underwent emergency surgery to remove the bullet and to repair his lung. The president remained in good humor, and he reportedly told his wife Nancy, “Honey, I forgot to duck” (a line first attributed to the boxing heavyweight Jack Dempsey when he lost the title to Gene Tunney in 1926), and to his doctors he said, “Please tell me you’re Republicans.” He was a loyal Conservative all his life.

Over the course of our nation’s history, we have managed to keep most of our presidents safe. Out of 45 Presidents of the United States, 4 were assassinated, and 6 others were shot while in office, but survived their attacks. Ronald Regan was the last United States President to be shot while in office. Reagan did not immediately realize that he had been shot…something that came as a shock to many. He was rushed to the hospital, where he underwent emergency surgery to remove the bullet and to repair his lung. The president remained in good humor, and he reportedly told his wife Nancy, “Honey, I forgot to duck” (a line first attributed to the boxing heavyweight Jack Dempsey when he lost the title to Gene Tunney in 1926), and to his doctors he said, “Please tell me you’re Republicans.” He was a loyal Conservative all his life.

John Hinckley, Jr. was a deranged individual with a crazed obsession for Jody Foster. Hinckley’s path toward the assassination attempt began in 1976 when he saw the movie Taxi Driver. In the movie, Robert DeNiro’s character, Travis Bickle stalks a Presidential candidate in the hopes that he will somehow impress and rescue a young prostitute played by Jodie Foster. Hinckley, who spent seven years in college without earning a degree or making a friend, added Foster to his list of obsessions, which also included Nazis, the Beatles, and assassins. In May 1980, Hinckley wrote to Foster while she attended Yale University, traveled there and talked to her on the phone at least once. Soon after, he began following President Jimmy Carter. In October, he was arrested at airport near a Carter campaign stop for carrying guns. However, the Secret Service was not notified. Hinckley  simply went to a pawnshop in Dallas and bought more guns. For the next several months, Hinckley’s plans changed daily. He pondered kidnapping Foster, considered killing Senator Edward Kennedy and began stalking newly elected President Reagan. Finally, he wrote a letter to Foster explaining that his attempt on Reagan’s life was for her. He kept abreast of the president’s schedule by reading the newspaper.

simply went to a pawnshop in Dallas and bought more guns. For the next several months, Hinckley’s plans changed daily. He pondered kidnapping Foster, considered killing Senator Edward Kennedy and began stalking newly elected President Reagan. Finally, he wrote a letter to Foster explaining that his attempt on Reagan’s life was for her. He kept abreast of the president’s schedule by reading the newspaper.

On March 30, 1981, Hinckley decided that he had found the perfect opportunity, and it turns out that he was right. Normally the President wears a bullet proof vest when entering and exiting engagements, but as it was only 30 feet to the limo, it was deemed unnecessary. Bad idea. Reagan stepped outside the Hilton Hotel in Washington D.C. where he had just addressed the Building and Construction Workers Union of the AFL-CIO. Hinckley was armed with a .22 revolver with exploding bullets and was only ten feet away from Reagan when he began shooting. Fortunately, he was a poor shot and most of the bullets did not explode as they were supposed to. Hinckley’s first shot hit press secretary James Brady in the head, critically wounding him, and other shots wounded a police officer and a Secret Service agent. The final shot hit Reagan’s limo and then ricocheted into the President’s chest. Hinckley had completely missed  Reagan, but “got lucky” when the bullet ricocheted. How he managed that is beyond the imagination, and not so “lucky” for President Reagan who, as he said, “Forgot to duck.” I also find it amazing that President Reagan could keep his sense of humor. It shows me what a man of grit he really was.

Reagan, but “got lucky” when the bullet ricocheted. How he managed that is beyond the imagination, and not so “lucky” for President Reagan who, as he said, “Forgot to duck.” I also find it amazing that President Reagan could keep his sense of humor. It shows me what a man of grit he really was.

Hinckley was also wounded police officer Thomas Delahanty and Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy. All of the shooting victims survived, although Brady’s 2014 death was later ruled a homicide 33 years after he was shot. Hinckley was later not found not guilty by reason of insanity. Hinckley was released from institutional psychiatric care on September 10, 2016, which I find astonishing. He currently lives with his mother.

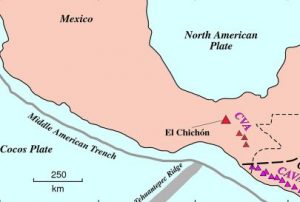

El Chichón was a volcano, in southern Mexico, that had not erupted for 130 years, meaning that no one who was alive on March 29, 1982 had ever seen it erupt. For most of the residents, who lived in the shadow of El Chichón, also known as Chinhonal, the 4,500 foot mountain seemed to pose no danger. Even when it did erupt, 130 years earlier, the eruption was minor. The people assumed that it was a dead volcano, and so ignored its potential for destruction and enjoyed the fertile soil its volcanic past provided.

El Chichón was a volcano, in southern Mexico, that had not erupted for 130 years, meaning that no one who was alive on March 29, 1982 had ever seen it erupt. For most of the residents, who lived in the shadow of El Chichón, also known as Chinhonal, the 4,500 foot mountain seemed to pose no danger. Even when it did erupt, 130 years earlier, the eruption was minor. The people assumed that it was a dead volcano, and so ignored its potential for destruction and enjoyed the fertile soil its volcanic past provided.

Then, in late 1981, two geologists, who were intrigued by hot springs and steaming gaps in the earth near the volcano, began an investigation that revealed increased seismic activity and the possibility of a major eruption of the volcano. Unfortunately, their report was ignored, because of the volcano’s quiet past. Thier complacence would  prove to be their downfall. Even when the ground began shaking on the night of March 28, the people did not heed the warning signs.

prove to be their downfall. Even when the ground began shaking on the night of March 28, the people did not heed the warning signs.

Then, at 5:15am the following morning, March 29, 1982, no one could miss the combination earthquake and eruption that exploded the mountain. The combination of the earthquake and the volcanic eruption turned the mountain into a crater. Ash was sent flying 60,000 feet in the air. About 150 people were killed when their roofs collapsed under raining volcanic debris. Two days later, ash from the eruption fell in Austin, Texas, many hundreds of miles to the north. The eruptions continued for over a week.

Most of the approximately 2,000 people killed by the eruption died from exposure to the pyroclastic flow, a  volatile mix of hot particles and gas. El Chichón lost its entire top, leaving only a large crater 1,000 feet deep, and less than 700 feet high, which was now shorter than the surrounding hills. Two more major eruptions occurred on April 3rd and 4th. In these eruptions, the debris was sent so high that it came down as virtual landslide on the surrounding villages. Trees and buildings were no match for the dirt and rocks. The debris also blocked streams, causing flooding in the area. Nine entire villages were destroyed and more than 100 square miles of farmland were unusable for years. Overall, the energy released by the eruptions, which were similar in scope to the Mount Saint Helens eruptions in Washington in 1980, was the equivalent of 8,000 one kiloton atomic bombs.

volatile mix of hot particles and gas. El Chichón lost its entire top, leaving only a large crater 1,000 feet deep, and less than 700 feet high, which was now shorter than the surrounding hills. Two more major eruptions occurred on April 3rd and 4th. In these eruptions, the debris was sent so high that it came down as virtual landslide on the surrounding villages. Trees and buildings were no match for the dirt and rocks. The debris also blocked streams, causing flooding in the area. Nine entire villages were destroyed and more than 100 square miles of farmland were unusable for years. Overall, the energy released by the eruptions, which were similar in scope to the Mount Saint Helens eruptions in Washington in 1980, was the equivalent of 8,000 one kiloton atomic bombs.

Before the 1830’s, food was preserved by salting, spicing, pickling or smoking. The people back then had no refrigerators, so butchers slaughtered meat only for the day’s trade, as preservation for longer periods was not practical unless you made jerky or something. Dairy products and fresh fruits and vegetables subject to spoilage were sold in local markets since storage and shipping farm produce over any significant distance or time was impossible. Milk was often hauled to city markets at night when temperatures were cooler. Ale and beer making required cool temperatures, so its manufacture was limited to the cooler months. The solution to these problems was found in the harvesting of natural ice.

Before the 1830’s, food was preserved by salting, spicing, pickling or smoking. The people back then had no refrigerators, so butchers slaughtered meat only for the day’s trade, as preservation for longer periods was not practical unless you made jerky or something. Dairy products and fresh fruits and vegetables subject to spoilage were sold in local markets since storage and shipping farm produce over any significant distance or time was impossible. Milk was often hauled to city markets at night when temperatures were cooler. Ale and beer making required cool temperatures, so its manufacture was limited to the cooler months. The solution to these problems was found in the harvesting of natural ice.

Before the invention of refrigerators in the early twentieth century, ice was harvested every winter from the lakes and stored in large ice houses, the proprietors then sold the ice to shippers of fresh fish, waterfowl, and produce for train deliveries to large cities. The ice harvesting process was labor intensive, requiring 20-100 men for one to four weeks. I suppose it was good temporarily, but was not permanent work.

Nineteenth-century ice harvesting began well before the actual cutting. As soon as the ice was strong and thick enough to support horses and equipment, work forces cleared away the insulating snow, sometimes many times, if necessary, to encourage the formation of stackable, thicker blocks. When the ice was thick enough, the field was marked in squares, using a horse-drawn marker, which scored slightly deeper into the ice, and finally the blocks were cut by hand with the use of large-toothed one-man saws. The blocks were then floated to the large adjacent commercial ice house for stacking, or to a railroad loading ramp for shipping. The system worked pretty well, and lasted throughout the century, the major change being the late introduction of rotary saws that replaced hand-cutting, making the job much easier.

The latter half of the 19th century saw many attempts to perfect manufactured ice methods. The Louisiana Ice Manufacturing Company appears to have been the first one to operate regularly, one of its claims being a price considerably lower than that of natural ice. Others followed. By 1925 factory-made ice had entered the realm of big business, and natural ice had become a thing of the past…just like that. In the 19th century commercial ice houses were constructed to provide ice for general use, to stock private ice houses when supplies from the local pool were scarce and later to produce “frozen” food. Some of these ice house’s were really a barn within a barn, with 3 feet of sawdust and hay between the inner and outer walls. City dwellers had ice delivered to them by horse and wagon. The iceman had to lift from 25 to 100 pound blocks, according to the order, which was placed by the consumer putting a numbered card in the window that corresponded with the number of pounds of ice they wanted. The ice was weighed on a spring scale on the truck, but an experienced delivery man could estimate the weight. The ice was carried to a kitchen using ice tongs, and chipped with chisels to fit the compartment of the ice box.

Delivery men were known for their brawn, as they hauled heavy blocks of ice all day long, and often up flights of stairs. Nevertheless, occasionally two women teams delivered the ice. They often had access to the kitchen when no one was home, and they simply placed the ice appropriately. Some city apartments used a suspended box (a small version of the ice box) outside the kitchen window, its contents available to the cook through the raised window; others kept an ice chest outdoors on the porch, or a handsome oak refrigerator in the kitchen. Ice wagons were great for children playing in summer’s heat. They loved when the iceman dropped his ice tongs and used his ice pick to chop a small piece of ice for them to suck on, similar to today’s ice cream trucks.

Residential ice boxes, many home-made, were of oak, pine, or ash wood lined with zinc, slate, porcelain, galvanized metal or wood. The insulator between the walls was charcoal, cork, flax straw or mineral wool. Still, the ice lasted only one day. Wooden boxes lined with tin or zinc and insulated with various materials including cork, sawdust, and seaweed were used to hold blocks of ice and “refrigerate” food. A drip pan collected the melt water…and had to be emptied daily. Electric refrigerators and freezers seriously hurt the ice industry. Although the first models were marketed before 1920. It would be a while before everyone had them, so ice delivery continued to be used, but declined yearly.

The Blitz was a German bombing offensive against Britain in 1940 and 1941, during World War II. The term was first used by the British press and is the German word for lightning. When the Germans bombed London in the Blitz bombing, the nerves of the people were very much on edge. They spent most of their nights in hiding in the subway tunnels. When they emerged, they had no idea what to expect. Most of them knew that their beloved city would be very different than it was before, and they knew that, in reality, it may never be the same. Yes, it could be rebuilt, but it would never…never be the same. The adults felt sick a they looked at the city they loved, but the

The Blitz was a German bombing offensive against Britain in 1940 and 1941, during World War II. The term was first used by the British press and is the German word for lightning. When the Germans bombed London in the Blitz bombing, the nerves of the people were very much on edge. They spent most of their nights in hiding in the subway tunnels. When they emerged, they had no idea what to expect. Most of them knew that their beloved city would be very different than it was before, and they knew that, in reality, it may never be the same. Yes, it could be rebuilt, but it would never…never be the same. The adults felt sick a they looked at the city they loved, but the  adults were not the only people who were looking at the devastation.

adults were not the only people who were looking at the devastation.

Some of the saddest pictures taken after the Blitz bombings, were those taken of the children. I can’t imagine what must have been going through their minds as they looked at the devastation that was once their home. They had spent so many wonderful hours playing in their bedrooms, and now they had no bedrooms, or even a house for that matter. Their home had been reduced to a pile of rubble. Sitting there looking at what little is left, some children find a little bit of solace in the fact that a doll or something similar managed to survive the carnage…and they feel somehow blessed. And, of course, they are blessed, because for so many others, there is nothing left.

I’m sure that those little ones looked to their parents, hoping to see a spark of hope, or a little bit of encouragement, but all they saw was a look of shock and disbelief on the  faces of their parents. That only served to create a deeper sense of concern in the children. What was going to happen to them now? Where would they live? And the really sad thing was that their parents are wondering the same things. These are the faces of war. We often think of the soldiers, usually facing off with the enemy. Yes, sometimes we think of the civilians, but most of us almost try not to think of them, because we can imagine what they are going through. The news photographers, however, have to see the civilians. They have to photograph the destruction. It is their job, but when we see those stories, with their necessary pictures, we really see how war affects the civilians, especially the children. And we are horrified.

faces of their parents. That only served to create a deeper sense of concern in the children. What was going to happen to them now? Where would they live? And the really sad thing was that their parents are wondering the same things. These are the faces of war. We often think of the soldiers, usually facing off with the enemy. Yes, sometimes we think of the civilians, but most of us almost try not to think of them, because we can imagine what they are going through. The news photographers, however, have to see the civilians. They have to photograph the destruction. It is their job, but when we see those stories, with their necessary pictures, we really see how war affects the civilians, especially the children. And we are horrified.

The Schienenzeppelin or rail zeppelin was an experimental railcar which resembled the Zeppelin airship. It was designed by the German aircraft engineer Franz Kruckenberg in 1929. The Schienenzeppelin was powered by a propeller located at the rear. The railcar accelerated to 143 mph setting the land speed record for a petroleum powered rail vehicle. Only one Schienenzeppelin was ever built due to safety concerns. It was never really put into service and was finally dismantled in 1939. The propeller, which powered the railcar, was also the source of concern for its safety. It was exposed, and so the concern was that someone might be hit by he propeller.

The Schienenzeppelin or rail zeppelin was an experimental railcar which resembled the Zeppelin airship. It was designed by the German aircraft engineer Franz Kruckenberg in 1929. The Schienenzeppelin was powered by a propeller located at the rear. The railcar accelerated to 143 mph setting the land speed record for a petroleum powered rail vehicle. Only one Schienenzeppelin was ever built due to safety concerns. It was never really put into service and was finally dismantled in 1939. The propeller, which powered the railcar, was also the source of concern for its safety. It was exposed, and so the concern was that someone might be hit by he propeller.

Anticipating the design of the Schienenzeppelin, the earlier Aerowagon, an experimental Russian high-speed railcar, was also equipped with an aircraft engine and a propeller. On 24 July 1921, a group of delegates to the First Congress of the Profintern, led by Fyodor Sergeyev, took the Aerowagon from Moscow to the Tula collieries to test it. Abakovsky was also on board. Although they successfully arrived in Tula on their maiden run, the return route to Moscow was not successful. The Aerowagon derailed at high speed near Serpukhov, killing six of the 22 people on board. A seventh man later died of his injuries.

The Schienenzeppelin railcar was built at the beginning of 1930 in the Hannover-Leinhausen works of the German Imperial Railway Company. The work was completed by Fall of that year. The vehicle was 84 feet 9 3/4 inches long and had just two axles, with a wheelbase of 64 feet 3 5/8  inches. The height was 9 feet 2 1/4 inches. It had two conjoined BMW IV 6-cylinder petroleum aircraft engines. The driveshaft was raised seven-degrees above the horizontal to give the vehicle some downwards thrust. The body of the Schienenzeppelin was streamlined, having some resemblance to the era’s popular Zeppelin airships, and it was built of aluminum in aircraft style to reduce weight. The railcar could carry up to 40 passengers. Its interior was designed in Bauhaus-style.

inches. The height was 9 feet 2 1/4 inches. It had two conjoined BMW IV 6-cylinder petroleum aircraft engines. The driveshaft was raised seven-degrees above the horizontal to give the vehicle some downwards thrust. The body of the Schienenzeppelin was streamlined, having some resemblance to the era’s popular Zeppelin airships, and it was built of aluminum in aircraft style to reduce weight. The railcar could carry up to 40 passengers. Its interior was designed in Bauhaus-style.

On May 10, 1931, the Schienenzeppelin exceeded a speed of 120 miles per hour for the first time. Afterwards, it toured Germany as an exhibit to the general public throughout Germany. There was still some concern due to the trains speed. On June 21, 1931, it set a new world railway speed record of 143 miles per hour on the Berlin–Hamburg line between Karstädt and Dergenthin, which was not surpassed by any other rail vehicle until 1954. The railcar still holds the land speed record for a petroleum powered rail vehicle. This high speed was attributable, in addition to other things, to its low weight, which was only 44800 pounds.

While several modifications were attempted, ultimately the Schienenzeppelin was scrapped. Due to many problems with the Schienenzeppelin prototype, the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft decided to go their own way in developing a high-speed railcar, leading to the Fliegender Hamburger (Flying Hamburger) in 1933. This new design was much more suitable for regular service and served also as the basis for later railcar developments. However, many of the Kruckenberg ideas were based on the experiments with Schienenzeppelin and high-speed rail travel, found their way into later DRG railcar designs.

The failure, if it could be called that, of Schienenzeppelin has been attributed to everything from the dangers of  using an open propeller in crowded railway stations to fierce competition between Kruckenberg’s company and the Deutsche Reichsbahn’s separate efforts to build high-speed railcars. Another disadvantage of the rail zeppelin was the inability to pull additional wagons to form a train, because of its construction. Furthermore, the vehicle could not use its propeller to climb steep gradients, as the flow would separate when full power was applied. Thus an additional means of propulsion was needed for such circumstances. Safety concerns have been associated with running high-speed railcars on old track network, with the inadvisability of reversing the vehicle, and with operating a propeller close to passengers.

using an open propeller in crowded railway stations to fierce competition between Kruckenberg’s company and the Deutsche Reichsbahn’s separate efforts to build high-speed railcars. Another disadvantage of the rail zeppelin was the inability to pull additional wagons to form a train, because of its construction. Furthermore, the vehicle could not use its propeller to climb steep gradients, as the flow would separate when full power was applied. Thus an additional means of propulsion was needed for such circumstances. Safety concerns have been associated with running high-speed railcars on old track network, with the inadvisability of reversing the vehicle, and with operating a propeller close to passengers.

For a long time, people in the 19th century, living in urban apartments, didn’t regularly take their children outside so they could get some fresh air. Then, the doctors started to recommend that these children really needed to get outside for fresh air. Now that doesn’t necessarily mean that the parents were real excited about the idea of loading up their child and taking them for a walk…just to get the recommended amount of fresh air. Nevertheless, it was important, as the doctors told them that it would strengthen their immune system, and with the number of pandemics that had gone around, the parents really tried to do whatever they could to make this happen.

For a long time, people in the 19th century, living in urban apartments, didn’t regularly take their children outside so they could get some fresh air. Then, the doctors started to recommend that these children really needed to get outside for fresh air. Now that doesn’t necessarily mean that the parents were real excited about the idea of loading up their child and taking them for a walk…just to get the recommended amount of fresh air. Nevertheless, it was important, as the doctors told them that it would strengthen their immune system, and with the number of pandemics that had gone around, the parents really tried to do whatever they could to make this happen.

While physicians such as Dr. Luther Emmett Holt advised simply placing an infant’s basket near an open window, some parents took it a step further. Enter the Baby Cage. The baby cage was just what it sounded like. It was a platform, with chicken wire all around it to keep the baby in. This whole contraption was then suspended outside the window…even if the window was on the sixth floor or something.  Personally, I can’t imagine hanging my baby outside my window for a dose of fresh air, but it was an actual thing in those days.

Personally, I can’t imagine hanging my baby outside my window for a dose of fresh air, but it was an actual thing in those days.

Eleanor Roosevelt, who by her own admission “knew absolutely nothing about handling or feeding a baby,” bought a chicken-wire cage after the birth of her daughter, Anna. She hung it out the window of her New York City apartment and placed Anna inside for her naps…until a concerned neighbor threatened to report her to the authorities. I would think so. If the brackets that suspended the cage to the window came loose…so long baby. I couldn’t find any incidence of such a thing happening, however. The first commercial patent for a baby cage was filed in 1922 by Emma Read of Spokane, Washington. The cages became popular in London in the 1930s among apartment dwellers without access to backyards. Ultimately, their popularity declined. It is possible that this was connected to safety concerns. As I said, I can imagine. I would have nightmares about that if it were my child.