When I think of some of the civilian heroes of our wars, I find myself amazed at the many courageous acts they carried out. They threw caution to the wind and moved about among the enemy, somehow managing to remain almost invisible. They had code names and secret pasts that no one knew about, not even the people they worked with…and definitely not the enemy they worked against.

When I think of some of the civilian heroes of our wars, I find myself amazed at the many courageous acts they carried out. They threw caution to the wind and moved about among the enemy, somehow managing to remain almost invisible. They had code names and secret pasts that no one knew about, not even the people they worked with…and definitely not the enemy they worked against.

One of these spies was Nancy Grace Augusta Wake, who was also known by her married name, Nancy Fiocca. Wake was a New Zealand-born nurse and journalist, who joined the French Resistance and later the Special Operations Executive (SOE) during World War II. Born August 30, 1912 in Roseneath, Wellington, New Zealand, the youngest of the six children of Charles Augustus Wake and Ella Rosieur Wake. In 1914, the family moved to Australia and settled at North Sydney. Shortly thereafter, Wake’s father returned to New Zealand and her mother raised the children. In Sydney, Wake attended the North Sydney Household Arts (Home Science) School.

At the age of 16, she ran away from home and worked as a nurse. With £200 (about $255.27) that she had inherited from an aunt, she traveled to New York City, then London where she trained herself as a journalist. In the 1930s, she worked in Paris and later for Hearst newspapers as a European correspondent. She witnessed the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi movement and “saw roving Nazi gangs randomly beating Jewish men and women in the streets” of Vienna. The Nazi movement repulsed her.

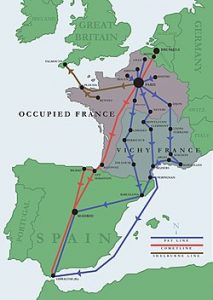

In 1937, Wake met wealthy French industrialist Henri Edmond Fiocca, whom she married on November 30, 1939. They were living in Marseille, France when Germany invaded. During the war in France, Wake served as an ambulance driver. After the fall of France in 1940, she joined the French Resistance, working in the escape network of Captain Ian Garrow, which became the Pat O’Leary Line. Wake had an incredible ability to elude capture, which earned her the nickname, “White Mouse” by the Gestapo. The Resistance exercised caution with her missions, because her life was in constant danger. The Gestapo tapped her telephone and intercepted her mail. In spite of the danger, Wake said, “I don’t see why we women should just wave our men a proud goodbye and then knit them balaclavas.” As a member of the escape network, she helped Allied airmen evade capture by the Germans and escape to neutral Spain.

In November 1942, Wehrmacht troops occupied the southern part of France after the Allies’ Operation Torch had started. This gave the Germans and the Gestapo unrestricted access to all parts of Vichy France and made life more dangerous for Wake. When the network was betrayed that same year she decided to flee France. Her husband, Henri Fiocca, stayed behind. He later was captured, tortured, and executed by the Gestapo. She threw caution to the wind. She would “doll” herself up and be very flirtatious, almost daring them to search her. She took a chance, and they couldn’t see past her façade to the ruthless spy beneath the beauty she showed on the outside.

In 1943, when the Germans became aware of her, she escaped to Spain and continued on to the United Kingdom. After reaching Britain, Wake joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE) under the code name Hélène. On April 29-30, 1944 as a member of a three person SOE team code-named “Freelance,” Wake parachuted into the Allier department of occupied France to liaise between the SOE and several Maquis groups in the Auvergne region, which were loosely overseen by Emile Coulaudon (code name “Gaspard”). She participated in a battle between the Maquis and a large German force in June 1944. In the aftermath of the battle, she bicycled 500 kilometers to send a situation report to SOE in London. In early 1943, in the process of getting out of France, Wake was picked up with a whole trainload of people and was arrested in Toulouse, but was released four days later. The head of the O’Leary Line, Albert Guérisse, managed to have her released by claiming she was his mistress and was trying to conceal her infidelity to her husband (all of which was untrue). She succeeded in crossing the Pyrenees to Spain. Until the war ended, she was unaware of her husband’s death, and she subsequently blamed herself for it. Wake was a recipient of the George Medal from the United Kingdom, the Medal of Freedom from the United States, the Legion of Honor from France, and medals from Australia and New Zealand.

In 1985, Wake published her autobiography, “The White Mouse.” Later, after 40 years of marriage, her second husband John Forward died at Port Macquarie on 19 August 1997. The couple had no children. Wake sold her medals to fund herself saying, “There was no point in keeping them, I’ll probably go to hell and they’d melt anyway.” Strangely, this disregard of the value of war medals, seemed common among the war spies. In 2001, Wake left Australia for the last time and emigrated to London. She became a resident at the Stafford Hotel in Saint James’ Place, near Piccadilly, formerly a British and American forces club during the war. She had been introduced to her first “bloody good drink” there by Louis Burdet, the general manager at the time, who had  also worked for the Resistance in Marseille. Mornings usually found Wake in the hotel bar, sipping her first gin and tonic of the day. She was welcomed at the hotel, celebrating her ninetieth birthday there. Out of deep respect for her, the hotel owners absorbed most of the costs of her stay. In 2003, Wake chose to move to the Royal Star and Garter Home for Disabled Ex-Service Men and Women, in Richmond, London, where she remained until her death on Sunday evening August 7, 2011, aged 98, at Kingston Hospital, where she had been admitted with a chest infection. She had requested that her ashes be scattered at Montluçon in central France. Her ashes were scattered near the village of Verneix, which is near Montluçon, on March 11, 2013.

also worked for the Resistance in Marseille. Mornings usually found Wake in the hotel bar, sipping her first gin and tonic of the day. She was welcomed at the hotel, celebrating her ninetieth birthday there. Out of deep respect for her, the hotel owners absorbed most of the costs of her stay. In 2003, Wake chose to move to the Royal Star and Garter Home for Disabled Ex-Service Men and Women, in Richmond, London, where she remained until her death on Sunday evening August 7, 2011, aged 98, at Kingston Hospital, where she had been admitted with a chest infection. She had requested that her ashes be scattered at Montluçon in central France. Her ashes were scattered near the village of Verneix, which is near Montluçon, on March 11, 2013.

Leave a Reply