government

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

So, the Soviet authorities deported German civilians from Germany and Eastern Europe to the USSR after World  War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

The decision was made and the fate of the German people was sealed. In 1946, the Soviet Union forcibly relocated more than 2,500 former Nazi German specialists, including scientists, engineers, and technicians who worked in specialist areas, from companies and institutions relevant to military and economic policy in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany (SBZ) and Berlin, along with around 4,000 family members, totaling more than 6,000 people, to the Soviet Union as war reparations. These specialists with all of their knowledge and abilities, could easily change the course of history in the Soviet Union, or any country they were placed in, for that matter. Still, not all of the forced labor were specialists. Many were unskilled labor, doing menial jobs.

The good thing was that the situation in Germany after World War II was appalling. Many of the people were homeless from the bombings. I suppose that, for that reason, the forced move, while scary, was not the worst thing in the world. It was possible that a new life in the Soviet Union could be favorable when compared to war-torn Germany. It is unclear whether any Germans who were sent to the Soviet Union chose to go back to Germany, because information about forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union was suppressed in the Eastern Bloc until after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Many of those records could have also been destroyed.

George Washington was not just our first president, but he was also an incredibly intelligent man. Normally, when George Washington spoke, people listened. Maybe his leadership was a big part of what made our system of government work so well, but there was one thing that everyone decided to ignore…his warnings about political parties. George Washington was against them, you see. He wasn’t just against one side of the political party system. He was against having political parties at all. He was so adamantly against them, that he remained nonpartisan throughout his entire presidency.

George Washington was not just our first president, but he was also an incredibly intelligent man. Normally, when George Washington spoke, people listened. Maybe his leadership was a big part of what made our system of government work so well, but there was one thing that everyone decided to ignore…his warnings about political parties. George Washington was against them, you see. He wasn’t just against one side of the political party system. He was against having political parties at all. He was so adamantly against them, that he remained nonpartisan throughout his entire presidency.

In his farewell address, President Washington said the following about partisan politics, “It serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens  the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus, the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.” Any of this sound familiar? Of course, it does. It is exactly what we have going on today.

the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus, the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.” Any of this sound familiar? Of course, it does. It is exactly what we have going on today.

I agree with President Washington, who worried that political parties would become too powerful, rob the people of their control over their own government, and distract everyone from what they should really be focusing on. In today’s political arena, that is exactly what is going on. People are being indited as a way of weaponizing politics. If someone doesn’t agree with the other party, or can’t be controlled, they are very likely to be politically ostracized and attacked. Since George Washington spoke those words, 250 years have passed, and there are people saying that they don’t trust either political party. I am one of those. I suppose some  people would wonder how we would elect our leaders. To them, I say, “How about electing them on their merits!!” There are people out there who will simply vote for the party they are affiliated with, no matter what their candidate stands for. They vote the way they vote, simply because the candidate they choose is from their party. What a horrible mistake that is. Isn’t it time that we find out what our candidates really stand for, and then vote our conscience? Isn’t it time we hold our politicians accountable for their actions? I think it is, but then we would have to find a way to get the correct information, and we already know that we can’t trust the media!! But that is another story.

people would wonder how we would elect our leaders. To them, I say, “How about electing them on their merits!!” There are people out there who will simply vote for the party they are affiliated with, no matter what their candidate stands for. They vote the way they vote, simply because the candidate they choose is from their party. What a horrible mistake that is. Isn’t it time that we find out what our candidates really stand for, and then vote our conscience? Isn’t it time we hold our politicians accountable for their actions? I think it is, but then we would have to find a way to get the correct information, and we already know that we can’t trust the media!! But that is another story.

In December of 2006, some 10,000 US researchers signed a statement protesting about political interference in the scientific process. In other words, the politicians were manipulating the scientific outcomes of research in order to sell their own agenda to the people. The statement, which included the backing of 52 Nobel Laureates, demanded a restoration of scientific integrity in government policy. These scientists were tired of being forced to have their research line up with the outcome that the government wanted. According to the American Union of Concerned Scientists, their research data is being misrepresented for political reasons. The statement claims that scientists working for federal agencies have been asked to change data to fit policy initiatives. Basically, these scientists are whistle blowers, who stand to lose their funding because they won’t play ball anymore, but science whose outcome is manipulated by politics isn’t science anymore anyway, is it.

In December of 2006, some 10,000 US researchers signed a statement protesting about political interference in the scientific process. In other words, the politicians were manipulating the scientific outcomes of research in order to sell their own agenda to the people. The statement, which included the backing of 52 Nobel Laureates, demanded a restoration of scientific integrity in government policy. These scientists were tired of being forced to have their research line up with the outcome that the government wanted. According to the American Union of Concerned Scientists, their research data is being misrepresented for political reasons. The statement claims that scientists working for federal agencies have been asked to change data to fit policy initiatives. Basically, these scientists are whistle blowers, who stand to lose their funding because they won’t play ball anymore, but science whose outcome is manipulated by politics isn’t science anymore anyway, is it.

In the statement the Union released, it included an “A to Z” guide that it says documents dozens of recent allegations involving censorship and political interference in federal science, covering issues ranging from global warming to sex education. When Congress won’t stand up for scientific integrity, it left the door open for the White House to censor the work of agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration. Dr Peter Gleick, president of the Pacific Institute for Studies in Development, Environment and Security said, “It’s very difficult to make good public policy without good science, and it’s even harder to make good public policy with bad science. In the last several years, we’ve seen an increase in both the misuse of science, and I would say an increase of bad science in a number of very important issues; for example, in global climate change, international peace and security, and water resources.”

The statement released at the American Geophysical Union’s Fall Meeting…the annual gathering of Earth scientists, triggered a major row when a discussion resulted in the renowned US space agency climate scientist Dr James Hansen claimed that he had come under pressure not to talk to the media on global warming issues. Michael Halpern from the UCS said the statement of objection to political interference had been supported by researchers regardless of their political views. Halpern said, “This science statement that has now been signed by the 10,000 scientists is signed by science advisers to both Republican and Democratic administrations dating back to President Eisenhower, stating that this is not business as usual and calling for this practice to stop.”

With the statement of objection, the Union expressed a hopefulness that the new Congress taking office that January would show a greater commitment to protecting the integrity of the scientific process. Unfortunately, I don’t think that has been the case with that Congress, nor with any others. Manipulating science to control the population seems to be the political way of doing things.

With the statement of objection, the Union expressed a hopefulness that the new Congress taking office that January would show a greater commitment to protecting the integrity of the scientific process. Unfortunately, I don’t think that has been the case with that Congress, nor with any others. Manipulating science to control the population seems to be the political way of doing things.

Pirates, as we know them, are criminals who hijack ships to rob them of anything of value on board. Sometimes however, a “pirate” can actually be working for the government, or at least on behalf of the government. Such was the case on April 10, 1778, when Commander John Paul Jones and his crew of 140 men aboard the USS Ranger set sail from the naval port at Brest, France. They headed toward the Irish Sea. Their mission was to begin raids on British warships. This was the first mission of its kind during the Revolutionary War. These missions weren’t called piracy, but when we compare the two acts, they pretty much were piracy. They just weren’t for personal gain, but rather for the good of the country and the war effort. No one was safe, not passengers and certainly not the crew.

Pirates, as we know them, are criminals who hijack ships to rob them of anything of value on board. Sometimes however, a “pirate” can actually be working for the government, or at least on behalf of the government. Such was the case on April 10, 1778, when Commander John Paul Jones and his crew of 140 men aboard the USS Ranger set sail from the naval port at Brest, France. They headed toward the Irish Sea. Their mission was to begin raids on British warships. This was the first mission of its kind during the Revolutionary War. These missions weren’t called piracy, but when we compare the two acts, they pretty much were piracy. They just weren’t for personal gain, but rather for the good of the country and the war effort. No one was safe, not passengers and certainly not the crew.

Commander John Paul Jones, will always be remembered as one of the most daring and successful naval commanders of the American Revolution. John Paul Jones was born under the simple birth name of John Paul on July 6, 1747, in a small cottage in Arbigland, Scotland, to John Paul Sr and Margaret Paul. His dad was a gardener, but Jones found his calling not in gardening, but at sea. He earned an apprenticeship with the British Merchant Marine at the age of 13. His seafaring adventures would eventually take him to America and, like many other sailors before him, Jones got involved in the slave trade. However, the realities of human trafficking repulsed him, and he returned to shipping cargo duties.

1773 found Jones in a very difficult situation. He murdered a mutinous sailor on the island of Tobago in self-defense…which is not really murder, but maybe in those days things were different. Whatever the case may be,  Jones believed he wouldn’t receive a fair trial, so he fled to America. It was there he added the last name “Jones” to conceal his identity. Jones needn’t have worried, because the American colonies were too busy stoking the flames of war with the British to have noticed his past. When the American Revolution broke out in 1775, Jones who remembered Britain’s cruel treatment of the Scots, decided that he would side with the colonists. He joined the new Continental Navy.

Jones believed he wouldn’t receive a fair trial, so he fled to America. It was there he added the last name “Jones” to conceal his identity. Jones needn’t have worried, because the American colonies were too busy stoking the flames of war with the British to have noticed his past. When the American Revolution broke out in 1775, Jones who remembered Britain’s cruel treatment of the Scots, decided that he would side with the colonists. He joined the new Continental Navy.

Jones began skillfully attacking British ships off the American coastline and expanded his operations from there. He first captained the USS Providence, set sail to Nova Scotia, and started capturing British vessels. Next, he took command of Ranger and set course to France, where his vessel was saluted by the French Admiral La Motte Piquet. It was the first American vessel ever to be recognized by a foreign power…pretty good for a new country. In 1779 Jones made history as one of the greatest naval commanders of the Revolutionary War. His shining moment came when, while En route to raid British shipping, Jones’ warship, Bon Homme Richard, came head to head with the more powerful English warship HMS Serapis off the North Sea. The battle went on for three hours between the two vessels. At one point, Jones slammed Bon Homme into Serapis, strategically tying them together. As the story goes, when the British asked if Jones was ready to surrender, he famously responded, “I have not yet begun to fight!” Inspired by Jones’ bravado, one of his naval officers tossed a grenade onto Serapis. The severe damage caused the British to surrender in the end. Jones’ became an  international hero. After the war ended, the Continental Navy dissolved due to lack of funds. Jones was dubbed the father of the United States Navy.

international hero. After the war ended, the Continental Navy dissolved due to lack of funds. Jones was dubbed the father of the United States Navy.

Jones retired to Paris, but his health took a turn for the worse. On July 18, 1792, he was found dead in his apartment at the age of 45. He was laid to rest in a French cemetery, but the plot of land was later sold and forgotten. Over one hundred years would pass before the United States was able to recover Jones’ remains with the help of French officials. After much research, his body was located and exhumed, and to the surprise of French pathologists, Jones’ body was excellently preserved. His initial autopsy concluded that the cause of his death was kidney failure, with later clinical studies believing his condition was exacerbated by a heart arrhythmia. The United States received Jones’ remains and buried them in a tomb inside the chapel of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

When we think of war heroes, civilians seldom come to mind. The reality is that there are many, many civilian heroes in any war. Each of those civilian heroes has their own reasons to take the actions they take. The one similarity is that most of them simply cannot continue to support a government that is committing the atrocities they commit, and so they have to take action, or they can’t look themselves in the mirror again. Sometimes, a change of heart comes because they see the cruelty of the country they live in. Other times, the change comes when they see that their countrymen are not even safe from their own government. Finally, completely disillusioned, they find themselves without alternative options, when they come face to face with the enemy within their own boarders.

When we think of war heroes, civilians seldom come to mind. The reality is that there are many, many civilian heroes in any war. Each of those civilian heroes has their own reasons to take the actions they take. The one similarity is that most of them simply cannot continue to support a government that is committing the atrocities they commit, and so they have to take action, or they can’t look themselves in the mirror again. Sometimes, a change of heart comes because they see the cruelty of the country they live in. Other times, the change comes when they see that their countrymen are not even safe from their own government. Finally, completely disillusioned, they find themselves without alternative options, when they come face to face with the enemy within their own boarders.

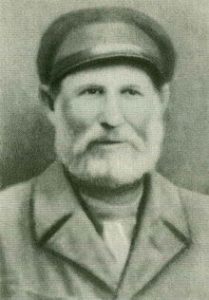

Matvey Kuzmich Kuzmin was born on August 3, 1858 in the village of Kurakino, in the Velikoluksky District of Pskov Oblast. He was a self-employed farmer who declined the offer to join a kolkhoz or collective farm. He lived with his grandson and continued to hunt and fish on the territory of the kolkhoz “Rassvet” (Dawn). He was nicknamed “Biriuk” (lone wolf).

During World War II, the area Kuzmin lived in was occupied by the forces of Nazi Germany. In February 1942, Kuzmin had to help house a German battalion in the village of Kurakino. The German unit was ordered to pierce the Soviet defense in the area of Velikiye Luki by advancing into the rear of the Soviet troops dug in at Malkino Heights. Kuzmin had to do what he had to do…like it or not. On February 13, 1942, the German commander asked the 83 year old Kuzmin to guide his men to the Malkino Heights area, and even offered Kuzmin money, flour, kerosene, and a “Three Rings” hunting rifle for doing so. Kuzmin agreed, but he knew that with information on the proposed route, he could make a difference. He sent his grandson Vasilij to Pershino, about 3.5 miles from Kurakino, to warn the Soviet troops and to propose an ambush near the village of Malkino.

The plan was for Kuzmin to guide the German units through straining paths, through the night. He lead them to  the outskirts of Malkino at dawn. When they arrived, the village defenders and the 2nd battalion of 31st Cadet Rifle Brigade of the Kalinin Front attacked. The German battalion came under heavy machine gun fire and suffered losses of about 50 killed and 20 captured. In the midst of the ambush, a German officer realized that they had been set up and turned his pistol towards Kuzmin. He shot him twice. Kuzmin died during the fight. He was buried three days later with military honors. Later, he was reburied at the military cemetery of Velikiye Luki. He was posthumously named a Hero of the Soviet Union on May 8, 1965, becoming the oldest person named a Hero of the Soviet Union based on his age at death.

the outskirts of Malkino at dawn. When they arrived, the village defenders and the 2nd battalion of 31st Cadet Rifle Brigade of the Kalinin Front attacked. The German battalion came under heavy machine gun fire and suffered losses of about 50 killed and 20 captured. In the midst of the ambush, a German officer realized that they had been set up and turned his pistol towards Kuzmin. He shot him twice. Kuzmin died during the fight. He was buried three days later with military honors. Later, he was reburied at the military cemetery of Velikiye Luki. He was posthumously named a Hero of the Soviet Union on May 8, 1965, becoming the oldest person named a Hero of the Soviet Union based on his age at death.

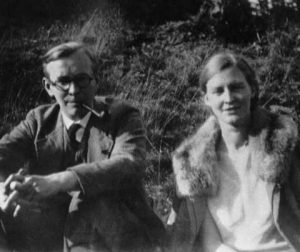

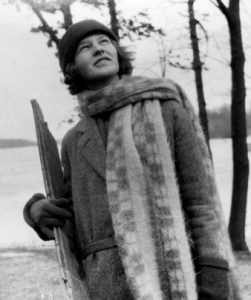

It was a big move for a Milwaukee, Wisconsin girl, but in the end, it would be her undoing. Mildred Fish was born in Milwaukee in 1902, and upon her high school graduation, she studied and then taught English at UW-Madison. It was there that she met Arvid Harnack, a Rockefeller Fellow from Germany. They soon fell in love, and were married in 1926. Because she was a progressive woman and proud of her name, Mildred chose to hyphenate her name, and became known as Mildred Fish-Harnack.

It was a big move for a Milwaukee, Wisconsin girl, but in the end, it would be her undoing. Mildred Fish was born in Milwaukee in 1902, and upon her high school graduation, she studied and then taught English at UW-Madison. It was there that she met Arvid Harnack, a Rockefeller Fellow from Germany. They soon fell in love, and were married in 1926. Because she was a progressive woman and proud of her name, Mildred chose to hyphenate her name, and became known as Mildred Fish-Harnack.

A few years later, she and Arvid both moved to Germany, where she taught and also worked on her doctorate while he worked for the German government. It was during those years that Fish-Harnack became interested in the Soviet Union, where women could choose where to work and also had other rights that women in the United States did not have…a situation which would very soon sound absurd. Nevertheless, at that time, it was so. Throughout the 1930s, Mildred and Arvid, who became increasingly  alarmed by Hitler’s rise to power, began to communicate with a close circle of associates who believed communism and the Soviet Union might be the only possible stumbling block to complete Nazi tyranny in Europe. As the Hitler and the Nazi regime began to come into power, Fish-Harnack and her husband joined a small resistance group, which the Nazi secret police…the Gestapo…would later call the Red Orchestra. This resistance group smuggled important secrets about the Nazis to the United States and Soviet governments and helped Jews escape from Germany. When war was declared in 1941, she did not leave with other American expatriates.

alarmed by Hitler’s rise to power, began to communicate with a close circle of associates who believed communism and the Soviet Union might be the only possible stumbling block to complete Nazi tyranny in Europe. As the Hitler and the Nazi regime began to come into power, Fish-Harnack and her husband joined a small resistance group, which the Nazi secret police…the Gestapo…would later call the Red Orchestra. This resistance group smuggled important secrets about the Nazis to the United States and Soviet governments and helped Jews escape from Germany. When war was declared in 1941, she did not leave with other American expatriates.

Of course, their activities were espionage and would eventually cost them their lives. For his part, her husband,  Arvid was hanged in December 1942. Mildred was given a six year sentence, but Hitler refused to endorse her punishment and she was retried and condemned on February 16, 1943. She was beheaded by guillotine. Because of her connection to possible communist sympathies and post-war McCarthyism, her story is virtually unknown in the United States. She was the only American woman who was ever put to death on the direct order of Adolf Hitler for her involvement in the resistance movement. Her last words were, “And I have loved Germany so much.” In the Cold War years after World War II, Fish-Harnack’s name and legacy were not honored in the United States, because she and her husband were believed to have been connected with Communism. For a time they were hated by both of their home countries. Once the truth came out in 1986, that changed and Mildred Fish-Harnack Day was established in Wisconsin. It takes place every year on her birthday, September 16th.

Arvid was hanged in December 1942. Mildred was given a six year sentence, but Hitler refused to endorse her punishment and she was retried and condemned on February 16, 1943. She was beheaded by guillotine. Because of her connection to possible communist sympathies and post-war McCarthyism, her story is virtually unknown in the United States. She was the only American woman who was ever put to death on the direct order of Adolf Hitler for her involvement in the resistance movement. Her last words were, “And I have loved Germany so much.” In the Cold War years after World War II, Fish-Harnack’s name and legacy were not honored in the United States, because she and her husband were believed to have been connected with Communism. For a time they were hated by both of their home countries. Once the truth came out in 1986, that changed and Mildred Fish-Harnack Day was established in Wisconsin. It takes place every year on her birthday, September 16th.

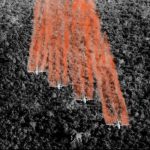

The Vietnam war was many things, but I don’t think anyone really expected Operation Ranch Hand…at least not the general public. Who would have expected such a heinous act to be carried out by the government. Operation Ranch Hand was a United States military operation during the Vietnam War, lasting from 1962 until 1971. The operation was largely inspired by the British use of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D (Agent Orange) during the Malayan Emergency in the 1950s. It was part of the overall program during the war called “Operation Trail Dust.” Ranch Hand involved spraying an estimated 20 million United States gallons of defoliants and herbicides over rural areas of South Vietnam in an attempt to deprive the Viet Cong of food and vegetation cover. Nearly 20,000 sorties were flown between 1961 and 1971.

The Vietnam war was many things, but I don’t think anyone really expected Operation Ranch Hand…at least not the general public. Who would have expected such a heinous act to be carried out by the government. Operation Ranch Hand was a United States military operation during the Vietnam War, lasting from 1962 until 1971. The operation was largely inspired by the British use of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D (Agent Orange) during the Malayan Emergency in the 1950s. It was part of the overall program during the war called “Operation Trail Dust.” Ranch Hand involved spraying an estimated 20 million United States gallons of defoliants and herbicides over rural areas of South Vietnam in an attempt to deprive the Viet Cong of food and vegetation cover. Nearly 20,000 sorties were flown between 1961 and 1971.

It’s hard to say if the government knew the consequences of the chemicals that were used. It’s possible that the chemicals were thought to just kill vegetation, and not to hurt people. The people involved were known as  Ranch Handers. I seriously doubt that at some point they didn’t wonder if what they were doing could possibly be harmful to the people they were spraying it on or near. Nevertheless, the “Ranch Handers” had a motto, “Only you can prevent a forest.” It was a take on the popular United States Forest Service poster slogan of Smokey Bear. During the ten years of spraying, over 5 million acres of forest and 500,000 acres of crops were heavily damaged or destroyed. Around 20% of the forests of South Vietnam were sprayed at least once.

Ranch Handers. I seriously doubt that at some point they didn’t wonder if what they were doing could possibly be harmful to the people they were spraying it on or near. Nevertheless, the “Ranch Handers” had a motto, “Only you can prevent a forest.” It was a take on the popular United States Forest Service poster slogan of Smokey Bear. During the ten years of spraying, over 5 million acres of forest and 500,000 acres of crops were heavily damaged or destroyed. Around 20% of the forests of South Vietnam were sprayed at least once.

The herbicides were sprayed by the United States Air Force flying C-123s using the call sign “Hades.” The planes were fitted with specially developed spray tanks with a capacity of 1,000 United States gallons of herbicides. A plane sprayed a swath of land that was ½ mile wide and 10 miles long in about 4½ minutes, at a rate of about 3 United States gallons per acre. Sorties usually consisted of three to five airplanes flying side by  side, and 95% of the herbicides and defoliants used in the war were sprayed by the United States Air Force as part of Operation Ranch Hand. The remaining 5% were sprayed by the United States Chemical Corps, other military branches, and the Republic of Vietnam using hand sprayers, spray trucks, helicopters and boats, primarily around United States military installations…meaning that the majority of the chemicals were exposed to the Untied States Military. Many of the Vietnam veterans have felt betrayed by their own government. Many have felt that the government was well aware of the dangers of the chemicals they were spraying. I don’t know if they knew or not, but it seems like they should have suspected something. Years later, the effects of Agent Orange are well known and it was vicious.

side, and 95% of the herbicides and defoliants used in the war were sprayed by the United States Air Force as part of Operation Ranch Hand. The remaining 5% were sprayed by the United States Chemical Corps, other military branches, and the Republic of Vietnam using hand sprayers, spray trucks, helicopters and boats, primarily around United States military installations…meaning that the majority of the chemicals were exposed to the Untied States Military. Many of the Vietnam veterans have felt betrayed by their own government. Many have felt that the government was well aware of the dangers of the chemicals they were spraying. I don’t know if they knew or not, but it seems like they should have suspected something. Years later, the effects of Agent Orange are well known and it was vicious.

During World War II, the Germans began a bombing campaign, during the Battle for Britain, that was known as the Blitzkrieg, which means lightning war. The name was often shortened to the Blitz. The Blitz began on September 7, 1940 and would continue until May 1941. During these bombing raids, London was especially badly hit. At the start of the campaign, the government did not allow the use of underground rail stations as shelters, as they considered them a potential safety hazard. However, the people of London took the matter into their own hands and opened up the chained entrances to the tube stations. In the Underground they were safe from the high explosive and incendiary bombs that rained down on London night after night. With one or two exceptions, their confidence was rewarded. The City tube station was hit when a bomb went through the road and fell into it. Over 200 were killed, but for the most part the tubes proved to be good bomb shelters.

During World War II, the Germans began a bombing campaign, during the Battle for Britain, that was known as the Blitzkrieg, which means lightning war. The name was often shortened to the Blitz. The Blitz began on September 7, 1940 and would continue until May 1941. During these bombing raids, London was especially badly hit. At the start of the campaign, the government did not allow the use of underground rail stations as shelters, as they considered them a potential safety hazard. However, the people of London took the matter into their own hands and opened up the chained entrances to the tube stations. In the Underground they were safe from the high explosive and incendiary bombs that rained down on London night after night. With one or two exceptions, their confidence was rewarded. The City tube station was hit when a bomb went through the road and fell into it. Over 200 were killed, but for the most part the tubes proved to be good bomb shelters.

One eyewitness to the tube shelters said, “By 4.00 p.m. all the platforms and passage space of the underground station are staked out, chiefly with blankets folded in long strips laid against the wall – for the trains are still running and the platforms in use. A woman or child guards places for about six people. When the evening comes the rest of the family crowd in.” To start with the government underestimated the potential use of the underground stations. The government estimated that 87% or more of people would use the issued shelters…usually Anderson shelters…or spaces under stairs, and such. They assumed that only 4% of the population would use the underground stations. However, each night underground stations played host to thousands of families in London grateful for the protection they afforded. On November 8, 1940, a request  went out for blankets to aid the people sleeping in these underground tunnels. Times were hard in many areas of the London, and many Londoners spent their winter nights in the underground tunnels and shelters. Supplies of any new or old blankets that could be spared were called for in order to provide additional warmth for these people.

went out for blankets to aid the people sleeping in these underground tunnels. Times were hard in many areas of the London, and many Londoners spent their winter nights in the underground tunnels and shelters. Supplies of any new or old blankets that could be spared were called for in order to provide additional warmth for these people.

London went into mandatory blackouts every night to try to be invisible to the bombers. Despite the blackout restrictions, the Luftwaffe had a relatively easy way of getting to London. They simply followed the route of the River Thames, which also directed them to the docks based at the East End of the city. Each night, the bombers first dropped incendiary bombs designed to give the following bombers the most obvious of markers. After the incendiary bombs, came the high explosives. The government used its control over all forms of the media to present a picture of life going on as normal despite the constant nightly attacks. I suppose some would call this fake news, but it was the governments way of making it look like the Germans weren’t making any headway. They did not show photos of people known as trekkers, the families who would spend the night away from their homes, preferably in local woodland or a park where they felt safer from attack. Such photos were censored. An American film called “London can take it” presented the image of a city devastated by bombs, but one that carried on as normal. The narrator makes the point that “bombs can only kill people, they cannot destroy the indomitable spirit of a nation.”

However, we know that in reality, life was not quite as easy as propaganda showed. Indeed, London could take it, but only because there was little else they could do. Under wartime restrictions, people could not simply  leave their homes and move elsewhere. The poorest in London lived in the East End, and it was this area that was especially hit hard by bombing because of the docks that were based there. However, most of the families there could do little else except stay where they were unless specifically moved by the government. These families developed what became known as a war-time spirit. They adapted their lives to the constant night-time bombing. By May 1941, 43,000 had been killed across Britain and 1.4 million had been made homeless. Not only was London attacked, but so were many British cities. Coventry and Plymouth were particularly badly bombed but most of Britain’s cities were also attacked, including Manchester, Glasgow, and Liverpool. Nevertheless, they were not broken.

leave their homes and move elsewhere. The poorest in London lived in the East End, and it was this area that was especially hit hard by bombing because of the docks that were based there. However, most of the families there could do little else except stay where they were unless specifically moved by the government. These families developed what became known as a war-time spirit. They adapted their lives to the constant night-time bombing. By May 1941, 43,000 had been killed across Britain and 1.4 million had been made homeless. Not only was London attacked, but so were many British cities. Coventry and Plymouth were particularly badly bombed but most of Britain’s cities were also attacked, including Manchester, Glasgow, and Liverpool. Nevertheless, they were not broken.

These days, being connected to the internet is commonplace. We connect from our computer, laptop, tablet, and even our phone. Many occupations, including the one I am in could not really function without the internet. When the computers go down, we are shut down too. For most of us, the internet is so much a part of our lives, that we simply cannot imagine life without it. Nevertheless, the reality is that until quite recently, there was no internet. I know people who think that might have been a better time, but I disagree. In fact, I think the people who say they think that, really have no idea just how bad that would be, and if they tried it once, they would change their minds quickly. People don’t realize how many things depend on the internet.

These days, being connected to the internet is commonplace. We connect from our computer, laptop, tablet, and even our phone. Many occupations, including the one I am in could not really function without the internet. When the computers go down, we are shut down too. For most of us, the internet is so much a part of our lives, that we simply cannot imagine life without it. Nevertheless, the reality is that until quite recently, there was no internet. I know people who think that might have been a better time, but I disagree. In fact, I think the people who say they think that, really have no idea just how bad that would be, and if they tried it once, they would change their minds quickly. People don’t realize how many things depend on the internet.

The first real idea of information available at our fingertips began to form on October 4, 1957, when the Soviet Union launched the world’s first manmade satellite into orbit. Known as Sputnik, the satellite did not do much. It tumbled aimlessly around in outer space, sending blips and bleeps from its radio transmitters as it circled the Earth. Nevertheless, to many Americans, the one foot diameter Sputnik was proof of something alarming. Up to this point, scientists and engineers in the United States had been designing bigger cars and better television sets, but the Soviets had been focusing on…less frivolous things, and they were going to win the Cold War because of it. Americans saw that information could eventually be transmitted back to the Soviets concerning American military and government secrets. It was the dawning of the age of spy satellites.

Sputnik’s launch, brought about the era of science and technology in America. In an effort to keep up, schools began teaching subjects like chemistry, physics and calculus. The government gave grants to corporations, who invested them in scientific research and development. The federal government formed new agencies, such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), to develop space-age technologies such as rockets, weapons and computers. Of course, the computer didn’t do nearly as much as it does these days, and it was the size of a small house. In 1962, a scientist from M.I.T. and ARPA named J.C.R. Licklider proposed a solution to this problem. His proposal  was a “galactic network” of computers that could talk to one another. Such a network would enable government leaders to communicate even if the Soviets destroyed the telephone system. Then came “packet switching.” Packet switching breaks data down into blocks, or packets, before sending it to its destination. That way, each packet can take its own route from place to place. Without packet switching, the government’s computer network, which is now known as the ARPAnet, would have been just as vulnerable to enemy attacks as the phone system. At least now computers did more, but they were still big.

was a “galactic network” of computers that could talk to one another. Such a network would enable government leaders to communicate even if the Soviets destroyed the telephone system. Then came “packet switching.” Packet switching breaks data down into blocks, or packets, before sending it to its destination. That way, each packet can take its own route from place to place. Without packet switching, the government’s computer network, which is now known as the ARPAnet, would have been just as vulnerable to enemy attacks as the phone system. At least now computers did more, but they were still big.

In 1969, ARPAnet delivered its first message. A “node-to-node” communication from one computer located in a research lab at UCLA, to the second located at Stanford. The message “LOGIN” was short and simple, and it crashed the ARPA network. Wow!! Things really are different today. The Stanford computer only received the note’s first two letters. By the end of 1969, just four computers were connected to the Arpanet. During the 1970s the network grew steadily. In 1971, it added the University of Hawaii’s ALOHAnet, and two years later it added networks at London’s University College and the Royal Radar Establishment in Norway. As packet-switched computer networks multiplied, it became more difficult for them to integrate into a single worldwide “Internet.” By the end of the 1970s, a computer scientist named Vinton Cerf had begun to solve this problem by developing a way for all of the computers on all of the world’s mini-networks to communicate with one another. He called his invention “Transmission Control Protocol,” or TCP. Later, he added an additional protocol, known as “Internet Protocol.” The acronym we use to refer to these today is TCP/IP. One writer describes Cerf’s protocol as “the ‘handshake’ that introduces distant and different computers to each other in a virtual space.”

Cerf’s protocol transformed the Internet into a worldwide network. Throughout the 1980s, researchers and scientists used it to send files and data from one computer to another. In 1991 the Internet changed again. That year, a computer programmer in Switzerland named Tim Berners-Lee introduced the World Wide Web…an Internet that was not simply a way to send files from one place to another, but was itself a “web” of information that anyone on the Internet could retrieve. Berners-Lee created the Internet that we know and use today. Since then, the Internet has changed in many ways, and will likely continue to change as time goes on.  In 1992, a group of students and researchers at the University of Illinois developed a browser that they called Mosaic, later known as Netscape. Mosaic offered a user-friendly way to search the Web. It allowed users to see words and pictures on the same page for the first time and to navigate using scrollbars and clickable links. Then Congress decided that the Web could be used for commercial purposes. Companies developed websites of their own, and e-commerce entrepreneurs began to use the Internet to sell goods directly to customers. These days, social networking sites like Facebook have become a popular way for people of all ages, including me, to stay connected. Today, almost one-third of the world’s 6.8 billion people use the Internet regularly.

In 1992, a group of students and researchers at the University of Illinois developed a browser that they called Mosaic, later known as Netscape. Mosaic offered a user-friendly way to search the Web. It allowed users to see words and pictures on the same page for the first time and to navigate using scrollbars and clickable links. Then Congress decided that the Web could be used for commercial purposes. Companies developed websites of their own, and e-commerce entrepreneurs began to use the Internet to sell goods directly to customers. These days, social networking sites like Facebook have become a popular way for people of all ages, including me, to stay connected. Today, almost one-third of the world’s 6.8 billion people use the Internet regularly.

As Americans began to expand to the West, new territories had to be opened for settlement. Of course, this was not always met with approval from the Indian nations who were living there at the time. Nevertheless, the settling of this nation would not be stopped, and while it was handled wrong in many ways, it was inevitable. Nearly two million acres of land in Oklahoma Territory had been preciously deemed unsuitable for white settlement, and so were given to the Native Americans who had been previously removed from their traditional lands to allow for white settlement. The relocations began in 1817. By the 1880s, Indian Territory was home to a variety of tribes, including the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Apache.

As Americans began to expand to the West, new territories had to be opened for settlement. Of course, this was not always met with approval from the Indian nations who were living there at the time. Nevertheless, the settling of this nation would not be stopped, and while it was handled wrong in many ways, it was inevitable. Nearly two million acres of land in Oklahoma Territory had been preciously deemed unsuitable for white settlement, and so were given to the Native Americans who had been previously removed from their traditional lands to allow for white settlement. The relocations began in 1817. By the 1880s, Indian Territory was home to a variety of tribes, including the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Apache.

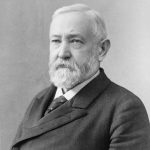

By the 1890s, with the improvements in agricultural and ranching techniques led some white Americans to realize that the Indian Territory land could be valuable, so they began to pressure the United States government to allow white settlement in the region. In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison agreed, making the first of a long series of authorizations that eventually removed most of Indian Territory from Indian control. To begin the process of white settlement, President Harrison chose to open a 1.9 million acre section of Indian Territory that the government had never assigned to any specific tribe. I suppose it was a way to ease into it without taking land from any specific tribe…initially anyway. However, subsequent openings of sections that  were designated to specific tribes were achieved primarily through the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, which allowed whites to settle large swaths of land that had previously been designated to specific Indian tribes.

were designated to specific tribes were achieved primarily through the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, which allowed whites to settle large swaths of land that had previously been designated to specific Indian tribes.

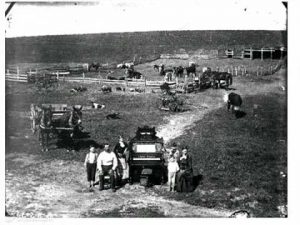

On March 3, 1889, Harrison announced the government would open the 1.9 million-acre tract of Indian Territory for settlement precisely at noon on April 22, 1889. Anyone could join the race for the land, but no one was supposed to jump the gun. With only seven weeks to prepare, the land-hungry Americans quickly began to gather around the borders of the irregular rectangle of territory. They were referred to as “Boomers,” and by the appointed day more than 50,000 hopefuls were living in tent cities on all four sides of the territory. At precisely high noon, thousands of would-be settlers make a mad dash into the newly opened Oklahoma Territory to claim cheap land. I can only imagine the chaos. The events that day at Fort Reno on the western border were typical of the entire process. At 11:50am, soldiers called for everyone to form a line. When the hands of the clock reached noon, the cannon of the fort boomed, and the soldiers signaled the settlers to start. With the crack of hundreds of whips, thousands of Boomers streamed into the territory in wagons, on horseback, and on foot. All told, from 50,000 to 60,000 settlers entered the territory that day. By nightfall, they had staked thousands of claims either on town lots or quarter section farm plots. Towns like Norman, Oklahoma City, Kingfisher, and Guthrie sprang into being almost overnight.

An extraordinary display of both the pioneer spirit and the American lust for land, the first Oklahoma land rush was also plagued by greed and fraud. Cases involving “Sooners,” who were people who had entered the territory before the legal date and time overloaded courts for years to come. I’m sure that the Indians weren’t pleased either, and I would imagine that there was periodic trouble over the whole process too. The government attempted to improve the operations of subsequent runs by adding more controls, finally adopting a lottery system to designate claims. By 1905, white Americans owned most of the land in Indian Territory. Two years later, the area once known as Indian Territory entered the Union as a part of the new state of Oklahoma.

An extraordinary display of both the pioneer spirit and the American lust for land, the first Oklahoma land rush was also plagued by greed and fraud. Cases involving “Sooners,” who were people who had entered the territory before the legal date and time overloaded courts for years to come. I’m sure that the Indians weren’t pleased either, and I would imagine that there was periodic trouble over the whole process too. The government attempted to improve the operations of subsequent runs by adding more controls, finally adopting a lottery system to designate claims. By 1905, white Americans owned most of the land in Indian Territory. Two years later, the area once known as Indian Territory entered the Union as a part of the new state of Oklahoma.