When people first began immigrating to the English Colonies, travel was not easy. In fact, sometimes it was absolutely treacherous. The only way to reach the new world was to travel by ship, and since storms were not able to be predicted far in advance, like they are these days, they sometimes found themselves at the mercy of the raging storm they were caught in. The first person known to have reached Bermuda was the Spanish sea captain Juan de Bermúdez in 1503. The islands are named after him. He claimed the islands for the Spanish Empire. De Bermúdez never landed on the islands, but made two visits to the island chain, and over the course of those visits, he created a recognizable map. I’m sure that at some point, de Bermúdez assumed that there would be people living on the islands, but it was not expected to be quite as soon as it was, or in quite the way that it was populated.

When people first began immigrating to the English Colonies, travel was not easy. In fact, sometimes it was absolutely treacherous. The only way to reach the new world was to travel by ship, and since storms were not able to be predicted far in advance, like they are these days, they sometimes found themselves at the mercy of the raging storm they were caught in. The first person known to have reached Bermuda was the Spanish sea captain Juan de Bermúdez in 1503. The islands are named after him. He claimed the islands for the Spanish Empire. De Bermúdez never landed on the islands, but made two visits to the island chain, and over the course of those visits, he created a recognizable map. I’m sure that at some point, de Bermúdez assumed that there would be people living on the islands, but it was not expected to be quite as soon as it was, or in quite the way that it was populated.

On July 28, 1609, a ship named Sea Ventureran into a reef that surrounds Bermuda during a hurricane. The ship was on its way to Jamestown, Virginia, but would not make it to that destination. The Sea Venture set out for Virginia on June 2, 1609, under the command of Sir George Somers, admiral of the fleet, with Christopher Newport as captain and Sir Thomas Gates, Governor of the colony. Sea Venture sailed with a fleet of ships, including the Falcon, Diamond, Swallow, Unity, Blessing, Lion, and two smaller ships. The ships were only eight days from the coast of Virginia, when they were suddenly caught in a hurricane. The Sea Venture became separated from the rest of the fleet, while its crew fought the storm for three days. Other ships the size of Sea Venture had successfully fought and survived such weather, but the Sea Venture had a one major problem. The Sea Venture was a new ship, and its timbers had not yet set. The storm forced the caulking from between the timbers, and the ship began to leak rapidly. The crew began desperately bailing, but water continued to pour into the hold. The crew threw some of the guns overboard in an effort to make the ship lighter, but this only delayed the inevitable.

The island was owned as an extension of Virginia by the Virginia Company until 1614. Then the Somers Isles Company, took over in 1615 and managed the colony until 1684. At that time, the company’s charter was  revoked, and England took over administration. Bermuda became a British colony following the 1707 unification of the parliaments of Scotland and England, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain. After 1949, when Newfoundland became part of Canada, Bermuda became the oldest remaining British overseas territory. After the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997, Bermuda became the most populated British territory. Today, Bermuda is a popular vacation spot for many tourists. Cruise ships and planes arrive daily. I’m sure the islands would have eventually been populated, but in the case of Bermuda, it was very much an accidental population, caused by an unfortunate ship wreck that first brought its survivors to the islands.

revoked, and England took over administration. Bermuda became a British colony following the 1707 unification of the parliaments of Scotland and England, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain. After 1949, when Newfoundland became part of Canada, Bermuda became the oldest remaining British overseas territory. After the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997, Bermuda became the most populated British territory. Today, Bermuda is a popular vacation spot for many tourists. Cruise ships and planes arrive daily. I’m sure the islands would have eventually been populated, but in the case of Bermuda, it was very much an accidental population, caused by an unfortunate ship wreck that first brought its survivors to the islands.

Recently, I discovered that Amelia Earhart is my 8th cousin once removed on my dad, Allen Spencer’s side of my family. Prior to this time, I knew of Amelia and her accomplishments, as well as her disappearance, but other than the fact that the whole thing was sad, it really didn’t affect me very much. Maybe it’s the fact that I now know that she is a relative, or maybe it’s the fact that the whole plot of the mystery seems to have thickened with some new information. Either way, I find myself intrigued by this new information.

Recently, I discovered that Amelia Earhart is my 8th cousin once removed on my dad, Allen Spencer’s side of my family. Prior to this time, I knew of Amelia and her accomplishments, as well as her disappearance, but other than the fact that the whole thing was sad, it really didn’t affect me very much. Maybe it’s the fact that I now know that she is a relative, or maybe it’s the fact that the whole plot of the mystery seems to have thickened with some new information. Either way, I find myself intrigued by this new information.

Amelia Earhart vanished eighty years ago. She was last heard from on July 2, 1937. It was assumed that her plane had crashed during an attempt to become the first woman to circumnavigate the globe, and since she was never heard from again, most people, myself included, were sure that she had crashed. For eighty years, it was pretty much settled…until someone looked at a photograph in a long forgotten file, that suggests that she may not have crashed, but rather crash landed in the Marshall Islands, and was possibly taken prisoner, along with her navigator. The photo, found in a long-forgotten file in the National Archives, shows a woman who resembles Earhart and a man who appears to be her navigator, Fred Noonan, on a dock. The discovery is featured in a new History channel special, “Amelia Earhart: The Lost Evidence.”

The photograph suggests that Amelia Earhart, survived a crash landing in the Marshall Islands. I’m sure there are many people who doubt the authenticity of the photograph, but independent analysts told the History Channel that the photo appears legitimate and undoctored. Shawn Henry, former executive assistant director for the FBI and an NBC News analyst, has studied the photo and feels confident it shows the famed pilot and her navigator. Henry told NBC news, “When you pull out, and when you see the analysis that’s been done, I think it leaves no doubt to the viewers that that’s Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan.”

These days, with so much fake news, and so much speculation about things, it’s hard to believe things sometimes. Still, so much of this evidence seems to point to facts very different from the theories we have  believed to be truth for so long. We know that Earhart was last heard from on July 2, 1937, as she made her quest to become the first woman pilot to circumnavigate the globe. She was declared dead two years later after the United States concluded she had crashed somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, but her remains were never found. Now, these investigators believe they have found evidence that Earhart and Noonan were blown off course, but survived the ordeal. The investigative team behind the History channel special believes the photo may have been taken by some secret spy for the United States on Japanese military activity in the Pacific. It is not clear how Earhart and Noonan could have flown so far off course.

believed to be truth for so long. We know that Earhart was last heard from on July 2, 1937, as she made her quest to become the first woman pilot to circumnavigate the globe. She was declared dead two years later after the United States concluded she had crashed somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, but her remains were never found. Now, these investigators believe they have found evidence that Earhart and Noonan were blown off course, but survived the ordeal. The investigative team behind the History channel special believes the photo may have been taken by some secret spy for the United States on Japanese military activity in the Pacific. It is not clear how Earhart and Noonan could have flown so far off course.

Les Kinney, a retired government investigator has spent 15 years looking for Earhart clues, about what really happened to her. He said the photo “clearly indicates that Earhart was captured by the Japanese.” Japanese authorities told NBC News they have no record of Earhart being in their custody, but then it is doubtful that they would have been honest with us if they had her. The photo, marked “Jaluit Atoll” and believed to have been taken in 1937, shows a short-haired woman, believed to be Earhart, sitting on a dock with her back to the camera. Like Earhart, the woman was wearing pants, something for which Earhart was known, even though it was odd in those days. Near her is a standing man who looks like Noonan, so much so that when a transparent photo of him fits it perfectly…down to the hairline. “The hairline is the most distinctive characteristic,” said Ken Gibson, a facial recognition expert who studied the image. “It’s a very sharp receding hairline. The nose is very prominent.” Gibson added, “It’s my feeling that this is very convincing evidence that this is probably Noonan.” The photo also shows a Japanese ship, Koshu, towing a barge with something that appears to be 38 feet long airplane…the same length as Earhart’s plane. The locals have continued to claim that they saw Earhart’s plane crash before she and Noonan were taken away. Native school kids insisted they saw Earhart in captivity. The story was even documented in postage stamps issued in the 1980s. “We believe that the Koshu took her to Saipan, in the [Mariana Islands], and that she died there under the custody of the  Japanese,” said Gary Tarpinian, the executive producer of the History special. “We don’t know how she died,” Tarpinian said. “We don’t know when.” Josephine Blanco Akiyama, who lived on Saipan as a child, has long claimed she saw Earhart in Japanese custody. “I didn’t even know it was a woman, I thought it was a man,” said Akiyama. “Everybody was talking about her — they were talking about in Japanese. That’s why I know that she’s a woman. They were talking about a woman flyer.” It is not clear if the United States government knew who was in the photo, or if it was taken by a spy, the United States may not have wanted to compromise that person by revealing the image. If that were the case, sadly two lives were sacrificed for one.

Japanese,” said Gary Tarpinian, the executive producer of the History special. “We don’t know how she died,” Tarpinian said. “We don’t know when.” Josephine Blanco Akiyama, who lived on Saipan as a child, has long claimed she saw Earhart in Japanese custody. “I didn’t even know it was a woman, I thought it was a man,” said Akiyama. “Everybody was talking about her — they were talking about in Japanese. That’s why I know that she’s a woman. They were talking about a woman flyer.” It is not clear if the United States government knew who was in the photo, or if it was taken by a spy, the United States may not have wanted to compromise that person by revealing the image. If that were the case, sadly two lives were sacrificed for one.

These days, since man has already been on the moon, I don’t suppose the scientists would feel the same excitement about seeing it through a telescope that they felt the first time they looked at it through a telescope. I’m sure that the creation of a map of the moon was an amazing accomplishment back in the 1600s. The earliest known telescope was built in 1608 in the Netherlands when an eyeglass maker named Hans Lippershey tried to obtain a patent on one. Although Lippershey did not receive his patent, news of the new invention soon spread across Europe. The design of these early refracting telescopes consisted of a convex objective lens and a concave eyepiece. The world was headed for a new and exciting journey that would someday put man in space and on the moon.

These days, since man has already been on the moon, I don’t suppose the scientists would feel the same excitement about seeing it through a telescope that they felt the first time they looked at it through a telescope. I’m sure that the creation of a map of the moon was an amazing accomplishment back in the 1600s. The earliest known telescope was built in 1608 in the Netherlands when an eyeglass maker named Hans Lippershey tried to obtain a patent on one. Although Lippershey did not receive his patent, news of the new invention soon spread across Europe. The design of these early refracting telescopes consisted of a convex objective lens and a concave eyepiece. The world was headed for a new and exciting journey that would someday put man in space and on the moon.

Thomas Harriot was a mathematician and astronomer who founded the English School of Algebra. He is described by some as “the greatest mathematician that Oxford has produced,” yet only recently has his name become widely known, and even now his achievements are not fully appreciated by most mathematicians. I’m sure he was an amazing mathematician, but it is his work in astronomy that interests me. As an undergraduate at Oxford, Harriot was a student at St Mary’s Hall. Harriot graduated in 1580 and went to London.

We know from manuscripts, belonging to Harriot, that he was engaged in deep studies of optics at Syon by  1597. Although in his manuscripts it states that he had discovered the sine law of refraction of light before 1597. The precise date of Harriot’s important discovery was July 1601. As with all his other mathematical discoveries, however, Harriot did not publish his findings. It is somewhat ironic, that Snell…to whom the discovery of this law is now attributed…was not the first to publish the result. Snell’s discovery was in 1621, about 20 years after Harriot’s discovery, but the result was not published until Descartes put it in print in 1637. He considered more complex systems and employed Christopher Tooke as a lens grinder from early 1605. His work on light now moved to the dispersion of light into colors. He began to develop a theory for the rainbow By 1606, Johannes Kepler had heard of the remarkable results on optics achieved by Harriot. Kepler wrote to Harriot, but the correspondence never really achieved any significant exchange of ideas. Perhaps Harriot was too wary of the difficulties that his work had nearly brought on him, or perhaps he did, as he claimed to Kepler, still intend to publish his results.

1597. Although in his manuscripts it states that he had discovered the sine law of refraction of light before 1597. The precise date of Harriot’s important discovery was July 1601. As with all his other mathematical discoveries, however, Harriot did not publish his findings. It is somewhat ironic, that Snell…to whom the discovery of this law is now attributed…was not the first to publish the result. Snell’s discovery was in 1621, about 20 years after Harriot’s discovery, but the result was not published until Descartes put it in print in 1637. He considered more complex systems and employed Christopher Tooke as a lens grinder from early 1605. His work on light now moved to the dispersion of light into colors. He began to develop a theory for the rainbow By 1606, Johannes Kepler had heard of the remarkable results on optics achieved by Harriot. Kepler wrote to Harriot, but the correspondence never really achieved any significant exchange of ideas. Perhaps Harriot was too wary of the difficulties that his work had nearly brought on him, or perhaps he did, as he claimed to Kepler, still intend to publish his results.

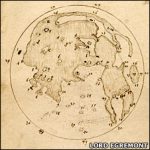

The appearance of a comet attracted Harriot’s attention and turned his scientific mind towards astronomy. He observed a comet on September 17, 1607 from Ilfracombe which would later be identified as Halley’s Comet.  Kepler had discovered the comet six days earlier, but it would be the observations of Harriot and his friend…and student, William Lower which eventually were used by Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel to compute its orbit. His astronomy was now back in the forefront of his mind, and Harriot went on to make the earliest telescopic observations in England. On July 26, 1609 at 9pm, he sketched the Moon, after viewing it through a telescope with a magnification of 6. He sketched the Moon again a year later on July 17, 1610, by this time he had a telescope giving him a magnification of 10. Soon he had constructed a telescope with a magnification of 20, then by April 1611 he had a 32 magnification telescope. While mapping the moon might seem to some like a minor achievement, it inspired him to continuously improve the telescope.

Kepler had discovered the comet six days earlier, but it would be the observations of Harriot and his friend…and student, William Lower which eventually were used by Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel to compute its orbit. His astronomy was now back in the forefront of his mind, and Harriot went on to make the earliest telescopic observations in England. On July 26, 1609 at 9pm, he sketched the Moon, after viewing it through a telescope with a magnification of 6. He sketched the Moon again a year later on July 17, 1610, by this time he had a telescope giving him a magnification of 10. Soon he had constructed a telescope with a magnification of 20, then by April 1611 he had a 32 magnification telescope. While mapping the moon might seem to some like a minor achievement, it inspired him to continuously improve the telescope.

On a clear night, ocean travel is really safe, because ships can see each other easily. Fog, however, presents a much different situation. Nevertheless, radar should solve any problem that fog can cause…right? Theoretically, yes, it should, but on the night of July 25, 1856, something went horribly wrong with that whole system, and the authorities were very puzzled as to the cause. At 11:00pm on that Wednesday night, 45 miles south of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts…with a heavy Atlantic fog hanging in the air, two ships carrying 2,453 people were just ten minutes from disaster.

On a clear night, ocean travel is really safe, because ships can see each other easily. Fog, however, presents a much different situation. Nevertheless, radar should solve any problem that fog can cause…right? Theoretically, yes, it should, but on the night of July 25, 1856, something went horribly wrong with that whole system, and the authorities were very puzzled as to the cause. At 11:00pm on that Wednesday night, 45 miles south of Nantucket Island, Massachusetts…with a heavy Atlantic fog hanging in the air, two ships carrying 2,453 people were just ten minutes from disaster.

In the mid-1950s, travel by steamer between Europe and America was commonplace. More than 50 passenger liners regularly made the transatlantic ocean voyage. The Andrea Doria was one of the most lavishly adorned steamers. Put to sea in 1953, it was the pride of the Italian line. It was built for luxury, not speed, and boasted extensive safety precautions, such as state-of-the-art radar systems and 11 watertight compartments in its hull. The Swedish ocean liner Stockholm, went into service in 1948. It was a more modest ocean liner, less than half the tonnage and carrying 747 passengers and crew on that fateful night. The Andrea Doria, by contrast carried 1,706 passengers and crew that night.

On the night of July 25, 1956, the Stockholm was beginning its journey home to Sweden from New York, while the Andrea Doria was steaming toward New York. The Andrea Doria had been in an intermittent fog since midafternoon, but Captain Piero Calami, relying on his ship’s radar to get him to his destination safely and on schedule, only slightly reduced his speed. At the same time, the Stockholm was directed north of its recommended route by Captain H. Gunnar Nordenson, who was trying to reduce his travel time. In so doing, he risked encountering westbound vessels. The Stockholm also had radar and expected no difficulty in navigating past approaching vessels. Captain Nordenson failed to anticipate that a ship like the Andrea Doria could be hidden until the last few minutes by a fogbank.

At 10:45pm, the Stockholm showed up on the Andrea Doria’s radar screens, about 17 nautical miles away. Soon after, the Andrea Doria showed up on the Stockholm’s radar, about 12 miles away. What happened next has been disputed, but it’s likely that the crews of both ships misread their radar sets. Captain Calami made a dangerous decision to turn the Andrea Doria to port for an unconventional starboard-to-starboard passing, which he erroneously thought the Stockholm was attempting. About two miles away from each other, the ship’s lights came into view of each other. Third Officer Johan-Ernst Bogislaus Carstens, commanding the bridge of the Stockholm, then made a conventional turn to starboard. Less than a mile away, Captain Calami realized he was on a collision course with the Stockholm and turned hard to the left, hoping to race past the bow of the Stockholm. Both ships were too large and moving too fast to make a quick turn. At 11:10pm, the Stockholm‘s sharply angled bow, reinforced for breaking ice, smashed 30 feet into the starboard side of the Andrea Doria. For a moment, the smaller ship was lodged there like a cork in a bottle. Then, the opposite momentum of the two ships pulled them apart, and the Stockholm‘s smashed bow screeched down the side of the Doria, sending sparks into the air.

Five crewmen of the Stockholm were killed in the collision. The Andrea Doria fared far worse. The bow of the Stockholm crashed through passenger cabins, and 46 passengers and crew were killed. One man watched as his wife was dragged away forever by the retreating bow of the Stockholm. Fourteen year old Linda Morgan was asleep on the Andrea Doria when the impact somehow threw her out of bed and onto the Stockholm’s crushed bow. She was later dubbed “the miracle girl” by the press. With seven of its 10 decks ripped open and exposed to the Atlantic waters, the Andrea Doria listed more than 20 degrees to port in minutes, and its watertight compartments were compromised. A lifeboat evacuation began on the doomed ship, but went far from smoothly. The port side could not be used because the ship was listing too much, which left lifeboat seats for 1,044 of the 1,706 people on board. Passengers in the lower cabins fought their way through darkened hallways quickly filling with ocean water and leaking oil. The first lifeboat was finally deployed an hour after the collision, and held more crew than passengers. Because the Stockholm had suffered a nonfatal  blow, it was able to lend its lifeboats to the evacuation effort. Several ships heard the Doria’s mayday and came to assist. At 2:00am on July 26, the Ile de France, another great ocean liner, arrived and took charge of the rescue effort. It was the greatest civilian maritime rescue in history, and 1,660 lives were saved. The Stockholm limped back to New York, damaged but afloat. At 10:09am on July 26, the Andrea Doria sank into the Atlantic. Almost immediately, the wreck, which is located at a depth of 240 feet of water, became a popular scuba diving destination. However, the Andrea Doria is known as the “Mount Everest” of diving locations, because of the extreme depth, the presence of sharks, and unpredictable currents.

blow, it was able to lend its lifeboats to the evacuation effort. Several ships heard the Doria’s mayday and came to assist. At 2:00am on July 26, the Ile de France, another great ocean liner, arrived and took charge of the rescue effort. It was the greatest civilian maritime rescue in history, and 1,660 lives were saved. The Stockholm limped back to New York, damaged but afloat. At 10:09am on July 26, the Andrea Doria sank into the Atlantic. Almost immediately, the wreck, which is located at a depth of 240 feet of water, became a popular scuba diving destination. However, the Andrea Doria is known as the “Mount Everest” of diving locations, because of the extreme depth, the presence of sharks, and unpredictable currents.

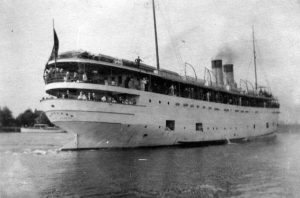

Shipwrecks on the Great Lakes are not a totally uncommon event. Over the last 300 years, Lake Michigan has claimed countless ships, mostly in violent storms and bad weather, especially when the gales of November come in. Nevertheless, a few ships went down without even reaching open waters. One of those ships was the SS Eastland, which went down while docked between LaSalle and Clark Streets on the Chicago River. That site and that ship became the site of the greatest loss of life on the Great Lakes, and it wasn’t a fire, explosion, or act of war, but rather something far more strange.

Shipwrecks on the Great Lakes are not a totally uncommon event. Over the last 300 years, Lake Michigan has claimed countless ships, mostly in violent storms and bad weather, especially when the gales of November come in. Nevertheless, a few ships went down without even reaching open waters. One of those ships was the SS Eastland, which went down while docked between LaSalle and Clark Streets on the Chicago River. That site and that ship became the site of the greatest loss of life on the Great Lakes, and it wasn’t a fire, explosion, or act of war, but rather something far more strange.

The SS Eastland was built by the Michigan Steamship Company in 1902 and began regular passenger service later that year. In July 1903, the ship held an open house so the public could have a look. The sudden number of people, particularly on the upper decks, caused the Eastland to list so severely that water came in through the gangways where passengers and freight would be brought aboard. The ship was obviously top-heavy and this problem had to dealt with quickly, but these incidences continued to plague the ship. In 1905, the Eastland was sold to the Michigan Transportation Company. During the summer of 1906, the Eastland listed again as it transported 2500 passengers, and her carrying capacity was reduced to 2400. But in July 1912, the Eastland was reported as having once more listed to port and then to starboard while carrying passengers. In 1915, the LaFollette Seaman’s Act, which was created as a response to the Titanic not carrying sufficient lifeboats, was passed. The Seaman’s Act mandated that lifeboat space would no longer depend on gross tonnage, but rather on how many passengers were on board. However adding extra weight to the ship put top-heavy vessels like the Eastland at greater risk of listing. In fact, the Senate Commerce Committee was cautioned at the time that placing additional lifeboats and life rafts on the top decks of Great Lakes ships would make them dangerously unstable. This was a warning that the Senate Committee and the Eastland should have heeded.

On July 24, 1915, the Eastland once again fell victim to its top heavy design, and this time the outcome was disastrous. On that cool Saturday morning in Chicago, the Eastland and two other steamers were waiting to take on passengers bound for an annual company picnic in Michigan City, Indiana. For many of the employees of Western Electric Company’s Hawthorne Works, this would be the only holiday they would enjoy all year. A large number of these employees from the 200-acre plant in Cicero, Illinois were Czech Bohemian immigrants. Excitement was in the air as thousands of employees thronged along the river. Three ships would transport them across Lake Michigan to the picnic grounds in Indiana. The Eastland was slated to be the first ship boarded. That morning the Eastland was docked between LaSalle and Clark Streets on the Chicago River. As soon as passengers began boarding, Captain Harry Pedersen and his crew noticed that the ship was listing to port even though most passengers were gathered along the starboard. Attempts were made to right the vessel, but stability seemed uncertain. At 7:10am, the ship reached its maximum carrying capacity of 2572 passengers and the gangplank was pulled in.

As the captain made preparations to depart at 7:21am, the crew continued to let water into the ship’s ballast tanks in an attempt to stabilize the vessel. At 7:23am, water began to pour in through the port gangways. Within minutes, the ship was seriously listing but most passengers seemed unaware of the danger. I wondered how this could have continued to happen, until I saw this video, that explained it very well. By 7:27am, the ship listed so badly that passengers found it too difficult to dance so the orchestra musicians started to play ragtime instead to keep everyone entertained. Just one minute later, at 7:28am, panic set in. Dishes crashed off shelves, a sliding piano almost crushed two passengers, and the band stopped playing as water poured through portholes and gangways. In the next two minutes, the ship completely rolled over on its side, and settled on the shallow river bottom 20 feet below. Passengers below deck now found themselves trapped as water gushed in and heavy furniture careened wildly. Men, women and children threw themselves into the river, but others were trapped between decks, or were crushed by the ship’s furniture and equipment. The lifeboats and life jackets were of no use since the ship had capsized too quickly to access them. In the end, 844 people lost their lives, including 22 entire families. It was a tragedy of epic proportions.

Bystanders on the pier rushed to help those who had been thrown into the river, while a tugboat rescued passengers clinging to the overturned hull of the ship. An eyewitness to the disaster wrote: “I shall never be able to forget what I saw. People were struggling in the water, clustered so thickly that they literally covered

the surface of the river. A few were swimming; the rest were floundering about, some clinging to a life raft that had floated free, others clutching at anything that they could reach…at bits of wood, at each other, grabbing each other, pulling each other down, and screaming! The screaming was the most horrible of them all.” Yes, I’m sure that was the worst, and the loss of life was something that would never be forgotten…especially for an eye witness.

the surface of the river. A few were swimming; the rest were floundering about, some clinging to a life raft that had floated free, others clutching at anything that they could reach…at bits of wood, at each other, grabbing each other, pulling each other down, and screaming! The screaming was the most horrible of them all.” Yes, I’m sure that was the worst, and the loss of life was something that would never be forgotten…especially for an eye witness.

After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first satellite, on October 4, 1957, inspiring the United States to keep up, or fall behind in the Cold War, the United States launched it’s first satellite on January 31, 1958. That satellite was called Explorer 1, and followed the first two Soviet satellites the previous year…Sputnik 1 and 2. It was the beginning the Cold War Space Race between the two nations. Explorer 1 had mercury batteries that powered the high-power transmitter for 31 days and the low-power transmitter for 105 days. Explorer 1 stopped transmission of data on May 23, 1958 when its batteries died, but remained in orbit for more than 12 years. It reentered the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on March 31, 1970 after more than 58,000 orbits. The Explorer 1 payload consisted of the Iowa Cosmic Ray Instrument. It was without a tape data recorder, which was not modified in time to make it onto the spacecraft. The real-time data received on the ground was therefore very sparse and puzzling showing normal counting rates and no counts at all. I’m not sure what the counting was all about, so I guess I’m more confused than the scientists were. The later Explorer 3 mission, which included a tape data recorder in the payload, provided the additional data for confirmation of the earlier Explorer 1 data.

After the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first satellite, on October 4, 1957, inspiring the United States to keep up, or fall behind in the Cold War, the United States launched it’s first satellite on January 31, 1958. That satellite was called Explorer 1, and followed the first two Soviet satellites the previous year…Sputnik 1 and 2. It was the beginning the Cold War Space Race between the two nations. Explorer 1 had mercury batteries that powered the high-power transmitter for 31 days and the low-power transmitter for 105 days. Explorer 1 stopped transmission of data on May 23, 1958 when its batteries died, but remained in orbit for more than 12 years. It reentered the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean on March 31, 1970 after more than 58,000 orbits. The Explorer 1 payload consisted of the Iowa Cosmic Ray Instrument. It was without a tape data recorder, which was not modified in time to make it onto the spacecraft. The real-time data received on the ground was therefore very sparse and puzzling showing normal counting rates and no counts at all. I’m not sure what the counting was all about, so I guess I’m more confused than the scientists were. The later Explorer 3 mission, which included a tape data recorder in the payload, provided the additional data for confirmation of the earlier Explorer 1 data.

Landsat 1, which was originally named “Earth Resources Technology Satellite 1”, was the first satellite in the United States’ Landsat program. It was the first satellite that was launched with the sole purpose of studying and monitoring the planet. Landsat 1 was a modified version of the Nimbus 4 meteorological satellite and was launched on July 23, 1972 by a Delta 900 rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Its orbit was near-polar and it served as a stabilized, Earth-oriented platform for obtaining information on agricultural and forestry resources, geology and mineral resources, hydrology and water resources, geography, cartography, environmental pollution, oceanography and marine resources, and meteorological phenomena. The spacecraft was placed in a sun-synchronous orbit, with an altitude between 564 and 569 miles. The spacecraft was placed in an orbit with an inclination of 99 degrees which orbited the Earth every 103 minutes. The project was renamed to Landsat in 1975.

Landsat 1 had two sensors to achieve its primary objectives…the return beam Vidicon (RBV) and the multispectral scanner (MSS). The RBV was manufactured by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). The RBV obtained visible light and near infrared photographic images of Earth. It was considered the primary sensor. The MSS sensor manufactured by Hughes Aircraft Company was considered an experimental and secondary sensor, until scientists reviewed the data that was beamed back to Earth. After the data was reviewed, the MSS  was considered the primary sensor. The MSS was a four-channel scanner that obtained radiometric images of Earth. From launch until 1974, Landsat 1 transmitted over 100,000 images, which covered more than 75% of the Earth’s surface. The RBV only took 1690 images. In 1976, Landsat 1 discovered a tiny uninhabited island 12 miles off the eastern coast of Canada. This island was named Landsat Island after the satellite. The MSS provided more than 300,000 images over the lifespan of the satellite. NASA oversaw 300 researchers that evaluated the data that Landsat 1 transmitted back to Earth. The Landsat 1 satellite sent data back to earth from its orbit until January of 1978 when its tape recorders malfunctioned. After that, it was taken out of service.

was considered the primary sensor. The MSS was a four-channel scanner that obtained radiometric images of Earth. From launch until 1974, Landsat 1 transmitted over 100,000 images, which covered more than 75% of the Earth’s surface. The RBV only took 1690 images. In 1976, Landsat 1 discovered a tiny uninhabited island 12 miles off the eastern coast of Canada. This island was named Landsat Island after the satellite. The MSS provided more than 300,000 images over the lifespan of the satellite. NASA oversaw 300 researchers that evaluated the data that Landsat 1 transmitted back to Earth. The Landsat 1 satellite sent data back to earth from its orbit until January of 1978 when its tape recorders malfunctioned. After that, it was taken out of service.

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

A radical pamphlet of mid-July read in part, “We are going to use a little direct action on the 22nd to show that militarism can’t be forced on us and our children without a violent protest.” It was in this environment that the Preparedness Parade found itself on July 22, 1916. In spite of that, the 3½ hour long procession of some 51,329 marchers, including 52 bands and 2,134 organizations, comprising military, civic, judicial, state and municipal divisions as well as newspaper, telephone, telegraph and streetcar unions, went ahead as planned. At 2:06pm, about a half hour after the parade began, a bomb concealed in a suitcase exploded on the west side of Steuart Street, just south of Market Street, near the Ferry Building. Ten bystanders were killed by the explosion, and 40 more were wounded, in what became the worst terrorist act in San Francisco history. The city and the nation were outraged, and they declared that justice would be served.

Two radical labor leaders, Thomas Mooney and Warren K Billings, were quickly arrested and tried for the  attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.

attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.

When we think of the Old West, cowboys, Indians, and outlaws come to mind…not to mention showdowns, or what might have been known as a duel, in years gone by. In reality, showdowns were not all that common…no matter what Hollywood tries to tell you. The men and women who went west were a tough bunch. In the beginning, it was mostly men who went west, and since there was no law in the West, altercations were bound to happen. Still, altercations that led to a showdown were not all that common. Rather than coolly confronting each other on a dusty street in a deadly game of quick draw, most men began shooting at each other in drunken brawls or spontaneous arguments. Ambushes and cowardly attacks were far more common than noble showdowns, but those who took the noble approach were far more respected.

When we think of the Old West, cowboys, Indians, and outlaws come to mind…not to mention showdowns, or what might have been known as a duel, in years gone by. In reality, showdowns were not all that common…no matter what Hollywood tries to tell you. The men and women who went west were a tough bunch. In the beginning, it was mostly men who went west, and since there was no law in the West, altercations were bound to happen. Still, altercations that led to a showdown were not all that common. Rather than coolly confronting each other on a dusty street in a deadly game of quick draw, most men began shooting at each other in drunken brawls or spontaneous arguments. Ambushes and cowardly attacks were far more common than noble showdowns, but those who took the noble approach were far more respected.

Southern emigrants brought to the West a crude form of the “code duello,” a highly formalized means of solving disputes between gentlemen with swords or guns that had its origins in European chivalry. Similar to the duels of times past, they thought it would bring some form of civility to the West. The duel influenced the informal western code of what constituted a legitimate and legal gun battle. Duels were not used to for very long. In fact, by the second half of the 19th century, few Americans still fought duels to solve their problems.  The western code required that a man resort to his six-gun only in defense of his honor or life, and only if his opponent was also armed. Also, a western jury was unlikely to convict a man in a shooting provided witnesses testified that his opponent had been the aggressor.

The western code required that a man resort to his six-gun only in defense of his honor or life, and only if his opponent was also armed. Also, a western jury was unlikely to convict a man in a shooting provided witnesses testified that his opponent had been the aggressor.

In what is thought to be the first western duel, Wild Bill Hickok, killed Davis Tutt on July 21, 1865. Hickok was a skilled gunman with a formidable reputation, who was eking out a living as a professional gambler in Springfield, Missouri. He quarreled with Tutt, a former Union soldier, but it is unclear what caused the dispute. Some people say it was over a card game while others say they fought over a woman. Whatever the cause, the two men agreed to a duel. The showdown took place the following day with crowd of onlookers watching as Hickok and Tutt confronted each other from opposite sides of the town square. When Tutt was about 75 yards away, Hickok shouted, “Don’t come any closer, Dave.” Tutt nervously drew his revolver and fired a shot that went wild. Hickok, by contrast, remained cool. He steadied his own revolver in his left hand and shot Tutt dead with a bullet through the chest. Hickok immediately turn and threatened Tutt’s friends…should they try to avenge his death.

Having adhered to the code of the West, Hickok was acquitted of manslaughter charges. Nevertheless, those were rough times, and just eleven years later, Hickok died in a fashion far more typical of the violence of the day. A young gunslinger shot him in the back of the head while he played cards. Legend says that the hand Hickok was holding at the time of his death was two pair…black aces and black eights. The hand would forever be known as the “dead man’s hand.” Jack McCall shot Hickok from behind as he played poker at Nuttal & Mann’s Saloon in Deadwood, Dakota Territory on August 2, 1876. In one shooting is honor, and in another is a dishonor. McCall was executed for the murder on March 1, 1877.

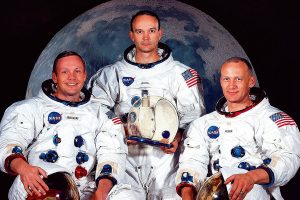

Most people know that at 10:56pm EDT, on July 20, 1969, American astronaut Neil Armstrong, 240,000 miles from Earth, speaks these words to more than a billion people listening at home, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Stepping off the lunar landing module Eagle, Armstrong became the first human to walk on the surface of the moon. The moment was historic, in more ways than one. Yes, the United States was the first nation to put a man on the moon. John F Kennedy’s dream had become a reality. On May 25, 1961, Kennedy made his famous appeal to a special joint session of Congress: “I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

Most people know that at 10:56pm EDT, on July 20, 1969, American astronaut Neil Armstrong, 240,000 miles from Earth, speaks these words to more than a billion people listening at home, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Stepping off the lunar landing module Eagle, Armstrong became the first human to walk on the surface of the moon. The moment was historic, in more ways than one. Yes, the United States was the first nation to put a man on the moon. John F Kennedy’s dream had become a reality. On May 25, 1961, Kennedy made his famous appeal to a special joint session of Congress: “I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.”

Most people know the rest of the story, or do they. At that moment, and for the next few moments, Neil Armstrong was the only human to step foot on the moon. He would always be the first human to step foot on the moon, but for a few minutes, he was the only human to do so. “Buzz” Aldrin joined him on the moon’s surface at 11:11pm, so now there were two humans who had walked on the moon, and while that was quite different from Armstrong’s feeling of being the only human to walk on the moon, it was still something so unique that I’m sure it had to be almost mind-boggling. Lots of us have done something that no one else in our  family or social circle has done, and the feeling of accomplishment is almost like a high, but this was something that no other human had ever done. Now that’s a high!! Of course, Armstrong wasn’t the only human to ever experience something like that. Many pioneers in different areas of history did the same thing. The first flight, the first car, the first heart transplant…the list goes on, but all of those had one thing in common. They were done on Earth. Armstrong was the first person to walk on a planet that was not the Earth. No matter how you look at it, this was unique, and Armstrong stood alone among human beings…not only for his accomplishment, but more for where it took place.

family or social circle has done, and the feeling of accomplishment is almost like a high, but this was something that no other human had ever done. Now that’s a high!! Of course, Armstrong wasn’t the only human to ever experience something like that. Many pioneers in different areas of history did the same thing. The first flight, the first car, the first heart transplant…the list goes on, but all of those had one thing in common. They were done on Earth. Armstrong was the first person to walk on a planet that was not the Earth. No matter how you look at it, this was unique, and Armstrong stood alone among human beings…not only for his accomplishment, but more for where it took place.

After “Buzz” Aldrin joined Neil Armstrong on the moon’s surface, they took photographs of the terrain, planted a United States flag on its surface. Then they ran a few simple scientific tests, and spoke with President Richard M Nixon via Houston. By 1:11am on July 21, both astronauts were back in the lunar module and the hatch was closed. The two men slept that night on the surface of the moon. Then, at 1:54pm the Eagle began its ascent back to the command module. Among the items left on the surface of the moon was a plaque that read: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot on the moon–July 1969 A.D–We came in peace for all mankind.” There would be five more successful lunar landing missions, and one unplanned lunar swing-by, when Apollo 13 experienced a malfunction that nearly made it impossible to return to Earth. The last men to walk on the moon, astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt of the Apollo 17 mission, left the lunar surface on December  14, 1972. In all, 12 men walked on the moon. All Americans, they were, on Apollo 11: Neil Armstrong (NASA Civilian) and Buzz Aldrin (USAF), on Apollo 12: Pete Conrad (US Navy) and Alan Bean (US Navy), on Apollo 14: Alan Shepard (US Navy) and Edgar Mitchell (US Navy), on Apollo 15: David Scott (USAF) and James Irwin (USAF), on Apollo 16: John Young (US Navy) and Charles Duke (USAF), and on Apollo 17: Gene Cernan (US Navy) and Harrison Schmitt (NASA Civilian). While Neil Armstrong was the only human to walk on the moon’s surface for 15 minutes in time, there were 11 others who had the distinct honor of walking on the moon, and while they weren’t the only humans, they were the only 12 humans to do so, and that had to feel really strange to them for the rest of their lives.

14, 1972. In all, 12 men walked on the moon. All Americans, they were, on Apollo 11: Neil Armstrong (NASA Civilian) and Buzz Aldrin (USAF), on Apollo 12: Pete Conrad (US Navy) and Alan Bean (US Navy), on Apollo 14: Alan Shepard (US Navy) and Edgar Mitchell (US Navy), on Apollo 15: David Scott (USAF) and James Irwin (USAF), on Apollo 16: John Young (US Navy) and Charles Duke (USAF), and on Apollo 17: Gene Cernan (US Navy) and Harrison Schmitt (NASA Civilian). While Neil Armstrong was the only human to walk on the moon’s surface for 15 minutes in time, there were 11 others who had the distinct honor of walking on the moon, and while they weren’t the only humans, they were the only 12 humans to do so, and that had to feel really strange to them for the rest of their lives.

These days, being connected to the internet is commonplace. We connect from our computer, laptop, tablet, and even our phone. Many occupations, including the one I am in could not really function without the internet. When the computers go down, we are shut down too. For most of us, the internet is so much a part of our lives, that we simply cannot imagine life without it. Nevertheless, the reality is that until quite recently, there was no internet. I know people who think that might have been a better time, but I disagree. In fact, I think the people who say they think that, really have no idea just how bad that would be, and if they tried it once, they would change their minds quickly. People don’t realize how many things depend on the internet.

These days, being connected to the internet is commonplace. We connect from our computer, laptop, tablet, and even our phone. Many occupations, including the one I am in could not really function without the internet. When the computers go down, we are shut down too. For most of us, the internet is so much a part of our lives, that we simply cannot imagine life without it. Nevertheless, the reality is that until quite recently, there was no internet. I know people who think that might have been a better time, but I disagree. In fact, I think the people who say they think that, really have no idea just how bad that would be, and if they tried it once, they would change their minds quickly. People don’t realize how many things depend on the internet.

The first real idea of information available at our fingertips began to form on October 4, 1957, when the Soviet Union launched the world’s first manmade satellite into orbit. Known as Sputnik, the satellite did not do much. It tumbled aimlessly around in outer space, sending blips and bleeps from its radio transmitters as it circled the Earth. Nevertheless, to many Americans, the one foot diameter Sputnik was proof of something alarming. Up to this point, scientists and engineers in the United States had been designing bigger cars and better television sets, but the Soviets had been focusing on…less frivolous things, and they were going to win the Cold War because of it. Americans saw that information could eventually be transmitted back to the Soviets concerning American military and government secrets. It was the dawning of the age of spy satellites.

Sputnik’s launch, brought about the era of science and technology in America. In an effort to keep up, schools began teaching subjects like chemistry, physics and calculus. The government gave grants to corporations, who invested them in scientific research and development. The federal government formed new agencies, such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), to develop space-age technologies such as rockets, weapons and computers. Of course, the computer didn’t do nearly as much as it does these days, and it was the size of a small house. In 1962, a scientist from M.I.T. and ARPA named J.C.R. Licklider proposed a solution to this problem. His proposal  was a “galactic network” of computers that could talk to one another. Such a network would enable government leaders to communicate even if the Soviets destroyed the telephone system. Then came “packet switching.” Packet switching breaks data down into blocks, or packets, before sending it to its destination. That way, each packet can take its own route from place to place. Without packet switching, the government’s computer network, which is now known as the ARPAnet, would have been just as vulnerable to enemy attacks as the phone system. At least now computers did more, but they were still big.

was a “galactic network” of computers that could talk to one another. Such a network would enable government leaders to communicate even if the Soviets destroyed the telephone system. Then came “packet switching.” Packet switching breaks data down into blocks, or packets, before sending it to its destination. That way, each packet can take its own route from place to place. Without packet switching, the government’s computer network, which is now known as the ARPAnet, would have been just as vulnerable to enemy attacks as the phone system. At least now computers did more, but they were still big.

In 1969, ARPAnet delivered its first message. A “node-to-node” communication from one computer located in a research lab at UCLA, to the second located at Stanford. The message “LOGIN” was short and simple, and it crashed the ARPA network. Wow!! Things really are different today. The Stanford computer only received the note’s first two letters. By the end of 1969, just four computers were connected to the Arpanet. During the 1970s the network grew steadily. In 1971, it added the University of Hawaii’s ALOHAnet, and two years later it added networks at London’s University College and the Royal Radar Establishment in Norway. As packet-switched computer networks multiplied, it became more difficult for them to integrate into a single worldwide “Internet.” By the end of the 1970s, a computer scientist named Vinton Cerf had begun to solve this problem by developing a way for all of the computers on all of the world’s mini-networks to communicate with one another. He called his invention “Transmission Control Protocol,” or TCP. Later, he added an additional protocol, known as “Internet Protocol.” The acronym we use to refer to these today is TCP/IP. One writer describes Cerf’s protocol as “the ‘handshake’ that introduces distant and different computers to each other in a virtual space.”

Cerf’s protocol transformed the Internet into a worldwide network. Throughout the 1980s, researchers and scientists used it to send files and data from one computer to another. In 1991 the Internet changed again. That year, a computer programmer in Switzerland named Tim Berners-Lee introduced the World Wide Web…an Internet that was not simply a way to send files from one place to another, but was itself a “web” of information that anyone on the Internet could retrieve. Berners-Lee created the Internet that we know and use today. Since then, the Internet has changed in many ways, and will likely continue to change as time goes on.  In 1992, a group of students and researchers at the University of Illinois developed a browser that they called Mosaic, later known as Netscape. Mosaic offered a user-friendly way to search the Web. It allowed users to see words and pictures on the same page for the first time and to navigate using scrollbars and clickable links. Then Congress decided that the Web could be used for commercial purposes. Companies developed websites of their own, and e-commerce entrepreneurs began to use the Internet to sell goods directly to customers. These days, social networking sites like Facebook have become a popular way for people of all ages, including me, to stay connected. Today, almost one-third of the world’s 6.8 billion people use the Internet regularly.

In 1992, a group of students and researchers at the University of Illinois developed a browser that they called Mosaic, later known as Netscape. Mosaic offered a user-friendly way to search the Web. It allowed users to see words and pictures on the same page for the first time and to navigate using scrollbars and clickable links. Then Congress decided that the Web could be used for commercial purposes. Companies developed websites of their own, and e-commerce entrepreneurs began to use the Internet to sell goods directly to customers. These days, social networking sites like Facebook have become a popular way for people of all ages, including me, to stay connected. Today, almost one-third of the world’s 6.8 billion people use the Internet regularly.