World War II

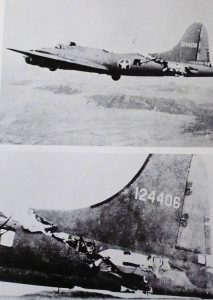

My dad was the top turret gunner and flight engineer on a B-17G Fortress Heavy Bomber during World War II. That was something that my family always knew. Dad didn’t talk much about it, but we were always very proud of him. What we didn’t know about all of that was that my dad was on the toughest plane ever built. At the time of his service, this little known fact probably wouldn’t have brought much comfort to his parents or siblings, but now, all these years later, it somehow brings a good measure of comfort to my dad’s daughter…me. My dad made it home from the war, of course. I know that there were times that his plane sustained damage, but it always brought the crew home.

My dad was the top turret gunner and flight engineer on a B-17G Fortress Heavy Bomber during World War II. That was something that my family always knew. Dad didn’t talk much about it, but we were always very proud of him. What we didn’t know about all of that was that my dad was on the toughest plane ever built. At the time of his service, this little known fact probably wouldn’t have brought much comfort to his parents or siblings, but now, all these years later, it somehow brings a good measure of comfort to my dad’s daughter…me. My dad made it home from the war, of course. I know that there were times that his plane sustained damage, but it always brought the crew home.

The testing of the B-17 Bomber, as is the case with most planes was rigorous. Is this great trial, the B-17 Flying Fortress put up one of most impressive displays, proving not only an effective carrier of firepower in which the plane delivered over a 3rd of the ordnance dropped by the allies in Europe and much of the ordnance dropped in the Pacific, but an astoundingly tough plane. Pilots and crews soon learned that the B-17s, which flew tens of thousands of missions under heavy anti-aircraft and fighter-plane pressure, could take extraordinary damage and still get home.

During the war years, the B-17s proved time and time again just what a wonderful plane they were. While they may not have brought their entire crew home every time they returned, they came home with part of them even with parts of the nose, propellers, and wings missing…and even with a tail that was hanging on by a thread. Of course, if the wing was torn completely off or the plane took a hit that ripped it in half, it did go down, but that is to be expected, as was the case with B-17G-15-BO “Wee Willie,” 322d BS, 91st BG, after direct flak hit on her 128th mission.

Still, the condition in which some of these planes came home would have shocked the builder altogether, if you ask me. I have looked at the pictures of these damaged planes, and I don’t know how they stayed in flight. The

“All American,” with the 97th Bomber Group, made without a doubt, the most astonishing return. The plane had a huge gash in it’s tail section from a collision with an enemy fighter, whose wing sliced almost completely through the fuselage. The tail gunner was trapped at the rear of the plane because the floor connecting his section to the rest of the plane was gone. The plane was piloted by Lieutenant Kendrick Bragg, who flew 90 minutes back to base with the tail barely hanging on. One crew member said that the tail wagged like a dog’s tail. The pilot, proceeded to drop his bombs, and then made a U-turn taking the plane in a wide turn over 70 miles, so as not to stress the tail. When the plane landed and came to a complete stop, the tail finally broke off. Now that is one tough plane!!

“All American,” with the 97th Bomber Group, made without a doubt, the most astonishing return. The plane had a huge gash in it’s tail section from a collision with an enemy fighter, whose wing sliced almost completely through the fuselage. The tail gunner was trapped at the rear of the plane because the floor connecting his section to the rest of the plane was gone. The plane was piloted by Lieutenant Kendrick Bragg, who flew 90 minutes back to base with the tail barely hanging on. One crew member said that the tail wagged like a dog’s tail. The pilot, proceeded to drop his bombs, and then made a U-turn taking the plane in a wide turn over 70 miles, so as not to stress the tail. When the plane landed and came to a complete stop, the tail finally broke off. Now that is one tough plane!!

The Blitz was a German bombing offensive against Britain in 1940 and 1941, during World War II. The term was first used by the British press and is the German word for lightning. When the Germans bombed London in the Blitz bombing, the nerves of the people were very much on edge. They spent most of their nights in hiding in the subway tunnels. When they emerged, they had no idea what to expect. Most of them knew that their beloved city would be very different than it was before, and they knew that, in reality, it may never be the same. Yes, it could be rebuilt, but it would never…never be the same. The adults felt sick a they looked at the city they loved, but the

The Blitz was a German bombing offensive against Britain in 1940 and 1941, during World War II. The term was first used by the British press and is the German word for lightning. When the Germans bombed London in the Blitz bombing, the nerves of the people were very much on edge. They spent most of their nights in hiding in the subway tunnels. When they emerged, they had no idea what to expect. Most of them knew that their beloved city would be very different than it was before, and they knew that, in reality, it may never be the same. Yes, it could be rebuilt, but it would never…never be the same. The adults felt sick a they looked at the city they loved, but the  adults were not the only people who were looking at the devastation.

adults were not the only people who were looking at the devastation.

Some of the saddest pictures taken after the Blitz bombings, were those taken of the children. I can’t imagine what must have been going through their minds as they looked at the devastation that was once their home. They had spent so many wonderful hours playing in their bedrooms, and now they had no bedrooms, or even a house for that matter. Their home had been reduced to a pile of rubble. Sitting there looking at what little is left, some children find a little bit of solace in the fact that a doll or something similar managed to survive the carnage…and they feel somehow blessed. And, of course, they are blessed, because for so many others, there is nothing left.

I’m sure that those little ones looked to their parents, hoping to see a spark of hope, or a little bit of encouragement, but all they saw was a look of shock and disbelief on the  faces of their parents. That only served to create a deeper sense of concern in the children. What was going to happen to them now? Where would they live? And the really sad thing was that their parents are wondering the same things. These are the faces of war. We often think of the soldiers, usually facing off with the enemy. Yes, sometimes we think of the civilians, but most of us almost try not to think of them, because we can imagine what they are going through. The news photographers, however, have to see the civilians. They have to photograph the destruction. It is their job, but when we see those stories, with their necessary pictures, we really see how war affects the civilians, especially the children. And we are horrified.

faces of their parents. That only served to create a deeper sense of concern in the children. What was going to happen to them now? Where would they live? And the really sad thing was that their parents are wondering the same things. These are the faces of war. We often think of the soldiers, usually facing off with the enemy. Yes, sometimes we think of the civilians, but most of us almost try not to think of them, because we can imagine what they are going through. The news photographers, however, have to see the civilians. They have to photograph the destruction. It is their job, but when we see those stories, with their necessary pictures, we really see how war affects the civilians, especially the children. And we are horrified.

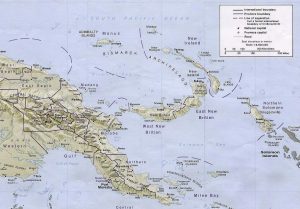

During World War II, the Japanese had a tendency to be very sneaky. Our troops had to watch them very closely, because if they could get into a position to execute a sneak attack, they would do it. Of course, war is war, and the whole idea of war is to get the drop on the enemy, and the Japanese were quite good at it. On 28 February 1943, a convoy, comprised of eight destroyers and eight troop transports with an escort of approximately 100 fighters, set out from Simpson Harbour in Rabaul. On March 1, 1943, United States reconnaissance planes spotted the 16 Japanese ships that were en route to Lae and Salamaua in New Guinea. The Japanese were attempting to keep from losing the island and their garrisons there by sending in 7,000 reinforcements and aircraft fuel and supplies. The Japanese convoy was a result of a Japanese Imperial General Headquarters decision in December 1942 to reinforce their position in the South West Pacific.

During World War II, the Japanese had a tendency to be very sneaky. Our troops had to watch them very closely, because if they could get into a position to execute a sneak attack, they would do it. Of course, war is war, and the whole idea of war is to get the drop on the enemy, and the Japanese were quite good at it. On 28 February 1943, a convoy, comprised of eight destroyers and eight troop transports with an escort of approximately 100 fighters, set out from Simpson Harbour in Rabaul. On March 1, 1943, United States reconnaissance planes spotted the 16 Japanese ships that were en route to Lae and Salamaua in New Guinea. The Japanese were attempting to keep from losing the island and their garrisons there by sending in 7,000 reinforcements and aircraft fuel and supplies. The Japanese convoy was a result of a Japanese Imperial General Headquarters decision in December 1942 to reinforce their position in the South West Pacific.

A United States bombing campaign, beginning March 2 and lasting until the March 4, consisting of 137 American bombers supported by United States and Australian fighters, destroyed eight Japanese troop transports and four Japanese destroyers. More than 3,000 Japanese troops and sailors drowned as a consequence, and the supplies sunk with their ships. Of 150 Japanese fighter planes that attempted to engage the American bombers, 102 were shot down. It was a complete and utter disaster for the Japanese. The United States 5th Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force dropped a total of 213 tons of bombs on the Japanese convoy. The Japanese made no further attempts to reinforce Lae by ship, greatly hindering their ultimately unsuccessful efforts to stop Allied offensives in New Guinea.

A United States bombing campaign, beginning March 2 and lasting until the March 4, consisting of 137 American bombers supported by United States and Australian fighters, destroyed eight Japanese troop transports and four Japanese destroyers. More than 3,000 Japanese troops and sailors drowned as a consequence, and the supplies sunk with their ships. Of 150 Japanese fighter planes that attempted to engage the American bombers, 102 were shot down. It was a complete and utter disaster for the Japanese. The United States 5th Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force dropped a total of 213 tons of bombs on the Japanese convoy. The Japanese made no further attempts to reinforce Lae by ship, greatly hindering their ultimately unsuccessful efforts to stop Allied offensives in New Guinea.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill chose March 4, the official end of the battle, to congratulate President Franklin D. Roosevelt, since that day was also the 10th anniversary of the president’s first inauguration. “Accept my warmest congratulations on your brilliant victory in the Pacific, which fitly salutes the end of your first 10 years.” President Franklin Roosevelt was one of the very few president who held the office of president for more than two terms…an almost unheard of amount of time, and a recipe for disaster with some presidents we have had. When you think about it, however, what a great way to mark his first inauguration.

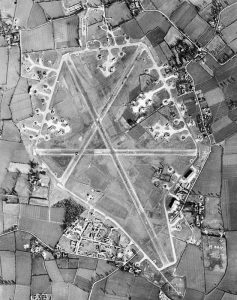

Most of the time, when we think of time and distance here on planet earth, we tend to feel like we are just a speck compared to the size of this planet, and I suppose that is true, but sometimes, our connection to one another is, in reality, much closer than we know. My dad, Allen L “Al” Spencer was a top turret gunner on a B-17G Bomber in World War II. He was stationed at Great Ashfield, Suffolk, England. I have always been very proud of my dad’s service, and because of his service, I have also always had an interest in other World War II bases in England.

Most of the time, when we think of time and distance here on planet earth, we tend to feel like we are just a speck compared to the size of this planet, and I suppose that is true, but sometimes, our connection to one another is, in reality, much closer than we know. My dad, Allen L “Al” Spencer was a top turret gunner on a B-17G Bomber in World War II. He was stationed at Great Ashfield, Suffolk, England. I have always been very proud of my dad’s service, and because of his service, I have also always had an interest in other World War II bases in England.

Yesterday, while researching my husband Bob’s great uncle, Richard F “Frank” Knox for his birthday today, I found myself reading his obituary again, looking for more information on a man I admired. I have always liked Frank very much, but because of the fact that we lived in Wyoming and they lived in Washington, I can’t say that I knew about his everyday life, and I certainly didn’t know about his military career. That said, while I had read the obituary right after his passing July 13, 2017, somehow it didn’t  hit me that he was stationed as a communications officer at RAF Horham, Suffolk, England. Of course, my curious mind had to go to Google Earth. I wanted to know if the Air Base was still visible, because most of them have been in one way or another returned to farm land. I did find the base, and while it’s outline isn’t as clearly marked as Great Ashfield is, I could pick out RAF Horham too. After finding the base, I was able to imagine a young Uncle Frank living and working there during the war. To me, that thought was very interesting, but another thing I noticed was the fact that Horham was not that far from Great Ashfield. In fact, my dad and Bob’s Uncle Frank were stationed a mere 22 miles away from each other. It is doubtful that they ever met, and if they did, they probably wouldn’t remember it, because it would be just in passing, but it occurs to me now, that the two men have probably met in Heaven, and they probably had some interesting stories to tell about their time in England.

hit me that he was stationed as a communications officer at RAF Horham, Suffolk, England. Of course, my curious mind had to go to Google Earth. I wanted to know if the Air Base was still visible, because most of them have been in one way or another returned to farm land. I did find the base, and while it’s outline isn’t as clearly marked as Great Ashfield is, I could pick out RAF Horham too. After finding the base, I was able to imagine a young Uncle Frank living and working there during the war. To me, that thought was very interesting, but another thing I noticed was the fact that Horham was not that far from Great Ashfield. In fact, my dad and Bob’s Uncle Frank were stationed a mere 22 miles away from each other. It is doubtful that they ever met, and if they did, they probably wouldn’t remember it, because it would be just in passing, but it occurs to me now, that the two men have probably met in Heaven, and they probably had some interesting stories to tell about their time in England.

As big as this old world is, and as unlikely as it seems that two families could have some close connections like this, I find that at least in my life, and my husband’s life, there are some connections, some very near misses, and some interesting encounters. Like my dad, Uncle Frank served out his time in the Army Air Forces right there

at RAF Horham, Suffolk, England. I imagine that like my dad, Frank took at least one leave to go and see London, because how could you go to England and not see London. Frank had a successful career in communications and then after his discharge from the service, four years, four months and four days of active duty, separating at war’s end with the rank of major. Frank served with distinction, earning a Bronze Star and the Air Medal, then he continued his military career in the Air Force Reserve. He retired in 1968 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Today would have been Uncle Frank’s 98th birthday, and it is his first in Heaven. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Frank. We love and miss you very much.

at RAF Horham, Suffolk, England. I imagine that like my dad, Frank took at least one leave to go and see London, because how could you go to England and not see London. Frank had a successful career in communications and then after his discharge from the service, four years, four months and four days of active duty, separating at war’s end with the rank of major. Frank served with distinction, earning a Bronze Star and the Air Medal, then he continued his military career in the Air Force Reserve. He retired in 1968 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Today would have been Uncle Frank’s 98th birthday, and it is his first in Heaven. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Frank. We love and miss you very much.

I don’t know…yet, if my son-in-law, Travis Royce has any connection to the Rolls-Royce families, but since my daughter, Amy Royce, and her husband Travis named their son Caalab Rolles Royce, I have felt a bit of a tie to the Rolls Royce vehicle line. Yes, my grandson’s middle name is spelled differently, but it makes it seem more like a last name and not a physical action. Because of my daughter’s family name, and my grandson’s name, I tend to read a story that is about the Rolls Royce. It just jumps out at me.

I don’t know…yet, if my son-in-law, Travis Royce has any connection to the Rolls-Royce families, but since my daughter, Amy Royce, and her husband Travis named their son Caalab Rolles Royce, I have felt a bit of a tie to the Rolls Royce vehicle line. Yes, my grandson’s middle name is spelled differently, but it makes it seem more like a last name and not a physical action. Because of my daughter’s family name, and my grandson’s name, I tend to read a story that is about the Rolls Royce. It just jumps out at me.

The Rolls-Royce cars are…high end elegance. They were first manufactured in 1904 By Henry Royce and Charles Rolls. These were not two men who were friends, and decided to build a car. Henry Royce was fourteen years older that Charles Rolls. He was a big, bearded, solid man, a workaholic and perfectionist, who worked hard for everything he had. As Rolls later said, he was “no ordinary man but a man of exceptional ingenuity and power of overcoming difficulties.” He was of Cambridgeshire farming stock…the son of a struggling miller. He had begun to earn money as a paper boy aged nine, somehow got an education at night school and took an engineering apprenticeship. Then he started an electrical engineering business in Manchester before designing and building his own car. It made an excellent impression for speed and reliability on a keen motorist named  Henry Edmunds, who knew Charles Rolls and more or less dragged him to meet Royce in Manchester. The two men became instant partners and agreed to form the Rolls-Royce car company. Rolls was so delighted with Royce’s quiet little two-cylinder car that he borrowed it on the spot, drove it back to London, woke Claude Johnson up in the middle of the night and insisted on giving him a ride in it. By the end of 1904 the first Rolls-Royces were came out, with the now characteristic radiator that would become the world’s best-known symbol of supreme motoring excellence.

Henry Edmunds, who knew Charles Rolls and more or less dragged him to meet Royce in Manchester. The two men became instant partners and agreed to form the Rolls-Royce car company. Rolls was so delighted with Royce’s quiet little two-cylinder car that he borrowed it on the spot, drove it back to London, woke Claude Johnson up in the middle of the night and insisted on giving him a ride in it. By the end of 1904 the first Rolls-Royces were came out, with the now characteristic radiator that would become the world’s best-known symbol of supreme motoring excellence.

The Silver Wraith was the first post-war Rolls-Royce. It was made from 1946 to 1958. It was designed for coachbuilders, and so was only a chassis. It was announced by Rolls-Royce in April 1946 as the 25/30 horsepower replacement for the 1939 Wraith in what had been their 20 horsepower and 20/25 horsepower market sector, that is to say Rolls-Royce’s smaller car. The size was chosen to be in keeping with the mood of post-war austerity. Even very limited production of the chassis of the larger car, the Phantom IV, was not resumed until 1950 and then, officially, only for Heads of State. The car had improvements, such as chromium-plated cylinder bores for the engine; a new more rigid chassis frame to go with new independent front suspension and a new synchromesh gearbox. The chassis now had centralized lubrication. The engine was a straight six-cylinder, which had been briefly made for the aborted by war Bentley Mark V. To this prewar mix Rolls-Royce added chromed bores. Initially, this engine had the Mark V’s capacity of 4,257 cc. It was increased from 1951 to 4,566 cc and in 1955, after the introduction of the Cloud, to 4,887 cc  for the remaining Silver Wraiths.

for the remaining Silver Wraiths.

Personally, I would love to find the connection between my grandson and Henry Royce, which I suspect exists. Of course, the whole family would be connected, but Caalab’s connection would be especially cool, because of the tie to his name. When he got old enough to think about cars, he told me that he was going to buy a 97 Rolls Royce for his name and birth year. I suppose he still could, but I think they are getting pretty scarce these days, at least for that specific year. Nevertheless, the Silver Wraith was never something Caalab was interested in, as far as I know.

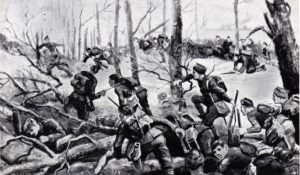

As a young battalion commander, Winston Churchill had a lot to learn about the facts of war. He was destined for greatness, and if he was to realize his destiny, he would have to learn many things. On January 17, 1916, he was battalion commander on the Western Front, when he attended a lecture on the Battle of Loos given by his friend, Colonel Tom Holland, in the Belgian town of Hazebrouck. It would be one of the first lessons, but the resulting knowledge might not be what we all would think. It was not about strategy or brave heroics, but rather of hopelessness.

As a young battalion commander, Winston Churchill had a lot to learn about the facts of war. He was destined for greatness, and if he was to realize his destiny, he would have to learn many things. On January 17, 1916, he was battalion commander on the Western Front, when he attended a lecture on the Battle of Loos given by his friend, Colonel Tom Holland, in the Belgian town of Hazebrouck. It would be one of the first lessons, but the resulting knowledge might not be what we all would think. It was not about strategy or brave heroics, but rather of hopelessness.

The Battle of Loos, which took place in September 1915, resulted in devastating casualties for the Allies and was taken by the British as a sign of the need to change their conduct of the war. In one major consequence, Sir John French was replaced by Sir Douglas Haig as British commander in the wake of that battle. “Tom spoke very well,” Churchill wrote to his wife, Clementine, “but his tale was one of hopeless failure, of sublime heroism utterly wasted and of splendid Scottish soldiers shorn away in vain with never the ghost of a chance of success. Afterwards they asked me what was the lesson of the lecture. I restrained an impulse to reply ‘Don’t do it again.’ But they will–I have no doubt.” What Churchill took away from the lecture was that in war, there is no winner…not really. There are losses on both sides, sometimes almost equal in number, so that the victory goes to the one who holds out the longest. Defeat comes in surrender.

Churchill had been demoted from First Lord of the Admiralty after the British plan to attempt a naval capture of the Turkish-controlled Dardanelle Straits met with resounding failure in mid-to-late 1915. Reduced to a minor ministerial position, Churchill resigned from the government in November 1915 and rejoined the army, heading  to the Western Front with the rank of lieutenant colonel. During his six months in Belgium, Churchill…who would later lead his country to victory in the World War II and be celebrated as the greatest political leader in British history, saw first-hand the hardships of war and the sacrifices that unknown, unheralded soldiers made for their country. More than once, he himself narrowly escaped death by an enemy shell. As he wrote to Clementine, “Twenty yards more to the left and no more tangles to unravel, no more anxieties to face, no more hatreds and injustices to encountera good ending to a chequered life, a final gift–unvalued–to an ungrateful country.” I find it amazing that a man so capable of “winning” a war, would count it as lost.

to the Western Front with the rank of lieutenant colonel. During his six months in Belgium, Churchill…who would later lead his country to victory in the World War II and be celebrated as the greatest political leader in British history, saw first-hand the hardships of war and the sacrifices that unknown, unheralded soldiers made for their country. More than once, he himself narrowly escaped death by an enemy shell. As he wrote to Clementine, “Twenty yards more to the left and no more tangles to unravel, no more anxieties to face, no more hatreds and injustices to encountera good ending to a chequered life, a final gift–unvalued–to an ungrateful country.” I find it amazing that a man so capable of “winning” a war, would count it as lost.

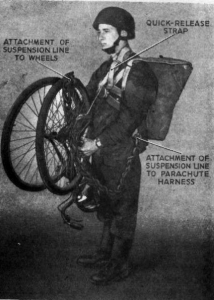

When we think about war machines, we think of planes, tanks, ships, and even horses, but we very seldom…if ever, think of bicycles. Nevertheless, bicycles were used in a number of wars, and even continue to be used to this day. The late 19th century brought several experiments into the possible role of bicycles and cycling within military establishments, primarily because they can carry more equipment and travel longer distances than walking soldiers could. The development of pneumatic tires coupled with shorter, sturdier frames in the late 19th century led military establishments to investigate the possibility of bicycles in combat. To some extent, bicyclists took over the functions of dragoons, especially as messengers and scouts, substituting for horses in warfare. Bicycle units or detachments were in existence by the end of the 19th century in most armies.

When we think about war machines, we think of planes, tanks, ships, and even horses, but we very seldom…if ever, think of bicycles. Nevertheless, bicycles were used in a number of wars, and even continue to be used to this day. The late 19th century brought several experiments into the possible role of bicycles and cycling within military establishments, primarily because they can carry more equipment and travel longer distances than walking soldiers could. The development of pneumatic tires coupled with shorter, sturdier frames in the late 19th century led military establishments to investigate the possibility of bicycles in combat. To some extent, bicyclists took over the functions of dragoons, especially as messengers and scouts, substituting for horses in warfare. Bicycle units or detachments were in existence by the end of the 19th century in most armies.

By World War I, the level terrain in Belgian was well used by military cyclists, prior to the onset of trench  warfare. Each of the four Belgian carabinier battalions included a company of cyclists, equipped with a brand of folding, portable bicycle named the Belgica. A regimental cyclist school gave training in map reading, reconnaissance, reporting, and the carrying of verbal messages. Attention was paid to the maintenance and repair of the machine itself. The bicycle could be used to ride when it was feasible, and carried when the pat was not suitable to riding. The bicycle made no noise, so unless the trail was littered with twigs, the bicycle make very little noise. Sneaking up on the enemy was possible.

warfare. Each of the four Belgian carabinier battalions included a company of cyclists, equipped with a brand of folding, portable bicycle named the Belgica. A regimental cyclist school gave training in map reading, reconnaissance, reporting, and the carrying of verbal messages. Attention was paid to the maintenance and repair of the machine itself. The bicycle could be used to ride when it was feasible, and carried when the pat was not suitable to riding. The bicycle made no noise, so unless the trail was littered with twigs, the bicycle make very little noise. Sneaking up on the enemy was possible.

In the United States, the most extensive experimentation on bicycle units was carried out by 1st Lieutenant Moss, of the 25th United States Infantry (Colored), which was made up of African American infantry soldiers with European American officers. Using a variety of cycle models, Moss and his troops carried out extensive bicycle journeys covering between 800 and 1,900 miles. Late in the 19th century, the United States Army tested the bicycle’s suitability for cross-country troop transport. Buffalo Soldiers stationed in Montana rode bicycles across roadless landscapes for hundreds of miles at high speed. The “wheelmen” traveled the 1,900 Miles to Saint Louis, Missouri in 34 days with an average speed of over 6 miles per hour. The bicycles were even used in the paratrooper deployment. These bicycles not only folded up, but they were equipped with an on board rifle. I don’t know how hard it was to handle a gun while riding a bike, but I’m sure it was a relief to have your gun right there.

The first known use of the bicycle in combat occurred during the Jameson Raid, in which cyclists carried messages. In the Second Boer War, military cyclists were used primarily as scouts and messengers. One unit  patrolled railroad lines on specially constructed tandem bicycles that were fixed to the rails. Several raids were conducted by cycle-mounted infantry on both sides; the most famous unit was the Theron se Verkenningskorps (Theron Reconnaissance Corps) or TVK, a Boer unit led by the scout Daniel Theron, whom British commander Lord Roberts described as “the hardest thorn in the flesh of the British advance.” Roberts placed a reward of £1,000 on Theron’s head…dead or alive…and dispatched 4,000 soldiers to find and eliminate the TVK. While scouting alone on a road near Gatsrand, about 3.7 miles north of present-day Fochville, he encountered seven members of Marshall’s Horse and was killed in action.

patrolled railroad lines on specially constructed tandem bicycles that were fixed to the rails. Several raids were conducted by cycle-mounted infantry on both sides; the most famous unit was the Theron se Verkenningskorps (Theron Reconnaissance Corps) or TVK, a Boer unit led by the scout Daniel Theron, whom British commander Lord Roberts described as “the hardest thorn in the flesh of the British advance.” Roberts placed a reward of £1,000 on Theron’s head…dead or alive…and dispatched 4,000 soldiers to find and eliminate the TVK. While scouting alone on a road near Gatsrand, about 3.7 miles north of present-day Fochville, he encountered seven members of Marshall’s Horse and was killed in action.

I always knew that my uncle, George Hushman served in the United States Navy during World War II, but like many of the men who fight in wars, discussing what happened during their deployment is something that few want to talk about. My family spent quite a bit of time with Uncle George and Aunt Evelyn, who was my mom’s sister, and their family, but in all those visits, I never heard my dad, Allen Spencer, or my Uncle George ever talk about their time in the war. In fact, had it not been for an old picture of the two couples going to the Military Ball, I don’t think I would have even known what branch of the military Uncle George was in.

I always knew that my uncle, George Hushman served in the United States Navy during World War II, but like many of the men who fight in wars, discussing what happened during their deployment is something that few want to talk about. My family spent quite a bit of time with Uncle George and Aunt Evelyn, who was my mom’s sister, and their family, but in all those visits, I never heard my dad, Allen Spencer, or my Uncle George ever talk about their time in the war. In fact, had it not been for an old picture of the two couples going to the Military Ball, I don’t think I would have even known what branch of the military Uncle George was in.

Recently, while researching my family history, I came across some Muster Rolls for the United States Navy, for one USS Gurke. The USS Gurke was a DD Type destroyer whose mission was to provide anti-submarine and anti-surface defense to other surface forces. The Gurke is one of 103 Gearing Class destroyers that were built at 8 different shipyards. It was originally laid down as USS John A. Bole in October of 1944, but was renamed USS Henry Gurke (DD-783) prior to her launching on February 15, 1945 at the Todd-Pacific Shipyards, Inc, in Tacoma, Washington. The ship’s sponsor was Mrs. Julius Gurke, mother of Private Gurke, for whom the ship was named. The destroyer was commissioned 12 May 1945, under the command of Commander  Kenneth Loveland. It was to this ship that my Uncle George was assigned beginning May 12, 1945. Prior to that he had been a S2c V6 on the USS LCI (G) 23, which was a transport ship.

Kenneth Loveland. It was to this ship that my Uncle George was assigned beginning May 12, 1945. Prior to that he had been a S2c V6 on the USS LCI (G) 23, which was a transport ship.

On the Gurke, Uncle George had a rating of S1c V6. I wasn’t sure what that meant, but I’m sure that any navy veteran would know. A V6 is a person who volunteered in World War II. As a V6 they had to be discharged by six months after the war was over. An S1c was a seamen first class. So now I knew what my uncle did during the war. Seaman first class was the rank right below a Petty Officer. The Seaman did a variety of jobs onboard the ship and could have worked anywhere on the ship. I suppose it would be a rank similar to the private, or in non-military verbiage, a laborer. That was the rank that many men went into the navy with, but a seaman first class was no longer a trainee. He had been trained to do his duties, and didn’t have to be told.

After a shakedown along the West Coast, the Gurke sailed for the Western Pacific August 27, 1945, reaching  Pearl Harbor on September 2nd. From there she continued west to participate in the occupation of Japan and former Japanese possessions. Returning to home port of San Diego, in February 1946, the Gurke participated in training operations until September 4, 1947, when she sailed for another WestPac cruise. Two further WestPac cruises, alternating with operations out of San Diego, and a cruise to Alaska in 1948 aiding the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Yukon gold rush, filled Gurke’s schedule until the outbreak of the Korean War. Of course, I assume that upon Gurke’s return to her home port of San Diego, my uncle was either assigned to another ship, was at home port, or discharged. I am very proud of his service. Today is Uncle George’s 93rd birthday. Happy birthday Uncle George!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Pearl Harbor on September 2nd. From there she continued west to participate in the occupation of Japan and former Japanese possessions. Returning to home port of San Diego, in February 1946, the Gurke participated in training operations until September 4, 1947, when she sailed for another WestPac cruise. Two further WestPac cruises, alternating with operations out of San Diego, and a cruise to Alaska in 1948 aiding the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Yukon gold rush, filled Gurke’s schedule until the outbreak of the Korean War. Of course, I assume that upon Gurke’s return to her home port of San Diego, my uncle was either assigned to another ship, was at home port, or discharged. I am very proud of his service. Today is Uncle George’s 93rd birthday. Happy birthday Uncle George!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Sometimes, when a war plane is in danger of being captured by the enemy, the pilot might take measures to destroy it, so that the technological secrets don’t end up in enemy hands. In fact, I believe that these days, anytime a plane goes down in enemy territory, the pilots are told to destroy them, but I’m not sure on that.

Sometimes, when a war plane is in danger of being captured by the enemy, the pilot might take measures to destroy it, so that the technological secrets don’t end up in enemy hands. In fact, I believe that these days, anytime a plane goes down in enemy territory, the pilots are told to destroy them, but I’m not sure on that.

Strange as that may seem to most of us, on November 27, 1942, something even more strange happened, but I’m getting ahead of myself. In June of 1940, after the German invasion of France and the establishment of an unoccupied zone in the southeast, which was led by General Philippe Petain, Admiral Jean Darlan was committed to keeping the French fleet out of German control. At the same time, as a minister in the government that had signed an armistice with the Germans, one that promised a relative “autonomy” to Vichy France, Darlan was prohibited from sailing that fleet to British or neutral waters. It put him in a rather precarious position, to say the least.

The British were as concerned as the French. A German-commandeered fleet in southern France, so close to British-controlled regions in North Africa, could prove disastrous to the British, who decided to take matters into their own hands by launching Operation Catapult…the attempt by a British naval force to persuade the French naval commander at Oran to either break the armistice and sail the French fleet out of the Germans’ grasp…or to scuttle it. And if the French wouldn’t, the Brits would. If you’ve ever heard the expression, “between a rock and a hard place,” you can picture this situation. And the British tried to push their way in it. In a five-minute missile bombardment, they managed to sink one French cruiser and two old battleships. They also killed 1,250 French sailors. This would be the source of much bad blood between France and England throughout the war. General Petain broke off diplomatic relations with Great Britain.

Two years later, the situation had worsened, with the Germans now in Vichy and the armistice already violated. Admiral Jean de Laborde finished the job the British had started. Just as the Germans launched Operation Lila…

the attempt to commandeer the French fleet, at Toulon harbor, off the southern coast of France, Laborde ordered the sinking of 2 battle cruisers, 4 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, 1 aircraft transport, 30 destroyers, and 16 submarines. Three French subs managed to escape the Germans and make it to Algiers, Allied territory. Only one sub fell into German hands. The marine equivalent of a scorched-earth policy had succeeded.

the attempt to commandeer the French fleet, at Toulon harbor, off the southern coast of France, Laborde ordered the sinking of 2 battle cruisers, 4 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, 1 aircraft transport, 30 destroyers, and 16 submarines. Three French subs managed to escape the Germans and make it to Algiers, Allied territory. Only one sub fell into German hands. The marine equivalent of a scorched-earth policy had succeeded.

New York City…a place as glamorous as any city in the world, the financial center of the world…and a target. Most of us know about the attacks on the World Trade Center in 1993, and again on September 11, 2001, but there was another attack that was planned for New York City, and in the end…foiled. This attack is most likely one you don’t recall…in fact, I think very few people even knew about it. The United States has enemies, as most nations do, and one of the best know enemies of the United States was Adolf Hitler.

New York City…a place as glamorous as any city in the world, the financial center of the world…and a target. Most of us know about the attacks on the World Trade Center in 1993, and again on September 11, 2001, but there was another attack that was planned for New York City, and in the end…foiled. This attack is most likely one you don’t recall…in fact, I think very few people even knew about it. The United States has enemies, as most nations do, and one of the best know enemies of the United States was Adolf Hitler.

According to an article I read recently, two men. Laureano Clavero and Pere Cardona, interviewed a Nazi pilot from World War II, who passed away in 2013. According to their research and their interview, the two claimed that they had proven the planned attack was real in an interview as they promoted their new book, The Diary of Peter Brill, a Nazi pilot during World War Two. In the interview, Peter Brill, who has been dubbed The Last Luftwaffe Pilot, claimed that Hitler was developing a plan to send a huge bomber from Germany to the United States. The New York mission has long been considered a myth, but Clavero and Cardona insist Brill admitted his involvement when they interviewed him. They claimed that Brill was a part of the secret project.

Clavero came across Brill and his history in 2010, when he was investigating the crash of two German bombers in the Pyrenees during the conflict. I’m always amazed at how often looking for one piece of information leads to another discovery. Brill agreed to give the authors an interview, and told them that he had been asked to take part in a secret mission to cross the Atlantic and launch the huge bombardment. While Brill was not specific, the two authors believe the project was convened in 1943, with Hitler’s enthusiastic support. The huge Heinkel plane was to be modified to allow it to fly 12,000 miles…the distance from Berlin to New York and back.

Brill and five others received top-secret training in the Polish city of Thorn, where they learned to fly at high altitude. They had to brave the frequent fires in the bomber’s engines. Before long, it became clear that the Heinkel was incapable of flying to New York and back. The authors claim that, when it became clear that the “Junker” could not fly such a long distance, the German engineers toyed with various workarounds, including  the creation of a halfway house and the coupling of the bomber to a Mescherschmitt. Nevertheless, it soon became clear to everyone that the mission would have to be scrapped, as there were more pressing difficulties taking precedence. “What is certain is that they were close to realizing their objective, but all the crazy dreams of Hitler were left to one side after the battle of Stalingrad,” Cardona said. “They were pushed aside for the day-to-day problems.” Clavero and Cardona have written their new book using the interviews given by Brill, and the memoirs gifted to them by his family when he died. The book sounds very interesting, and I, for one, plan to read about this…almost attack on New York City.

the creation of a halfway house and the coupling of the bomber to a Mescherschmitt. Nevertheless, it soon became clear to everyone that the mission would have to be scrapped, as there were more pressing difficulties taking precedence. “What is certain is that they were close to realizing their objective, but all the crazy dreams of Hitler were left to one side after the battle of Stalingrad,” Cardona said. “They were pushed aside for the day-to-day problems.” Clavero and Cardona have written their new book using the interviews given by Brill, and the memoirs gifted to them by his family when he died. The book sounds very interesting, and I, for one, plan to read about this…almost attack on New York City.