World War II

After World War II, the GIs who had fought in the war, came home, eager to start their lives over. Many went to the car dealerships to buy new cars, only to find that there were no new cars to be found. What a bizarre thought!! In my entire lifetime, I don’t know of a time that new cars weren’t available, but there was a reason for the lack of new cars.

After World War II, the GIs who had fought in the war, came home, eager to start their lives over. Many went to the car dealerships to buy new cars, only to find that there were no new cars to be found. What a bizarre thought!! In my entire lifetime, I don’t know of a time that new cars weren’t available, but there was a reason for the lack of new cars.

During World War II, the whole United States “kicked in” on the war effort. The automobile industry changed the production in their factories from automobiles to whatever was needed for the war effort. The United States automakers manufactured a wide variety of vehicles, munitions, and more  for the government. They made tanks like the Fisher Body Grand Blanc, the Ford M10 Wolverine, and the M18 Hellcat, which were produced by the Buick Motor Car Division of General Motors. Some of the automakers were tasked with producing parts for planes, including the infamous Enola Gay. The 18-foot nose section of the fuselage was built by Chrysler. Chevrolet alone produced 60,000 engines for Pratt and Whitney cargo and bomber planes between 1942 and 1945, along with 500,000 trucks, 8 million artillery shells, and much more. The tire company, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company produced the 40 mm cannon gun mount one of which was placed on the deck of the USS Cod, while another was mounted on the

for the government. They made tanks like the Fisher Body Grand Blanc, the Ford M10 Wolverine, and the M18 Hellcat, which were produced by the Buick Motor Car Division of General Motors. Some of the automakers were tasked with producing parts for planes, including the infamous Enola Gay. The 18-foot nose section of the fuselage was built by Chrysler. Chevrolet alone produced 60,000 engines for Pratt and Whitney cargo and bomber planes between 1942 and 1945, along with 500,000 trucks, 8 million artillery shells, and much more. The tire company, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company produced the 40 mm cannon gun mount one of which was placed on the deck of the USS Cod, while another was mounted on the  stern of PT-305. Pontiac Motor Car Division built aerial launched torpedoes at its facilities in Pontiac, Michigan.

stern of PT-305. Pontiac Motor Car Division built aerial launched torpedoes at its facilities in Pontiac, Michigan.

By the time the World War II ended in 1945, the total value of goods produced by the United States auto industry for the war would exceed $29 million, equal to nearly $400,000,000 today. There had been no new cars built in the United States between early 1942 and late 1945. Once the war was over, automakers were again free to begin manufacturing new cars for the American public. That was all well and good, but it would take time to bring production of automobiles back up to speed. The first car built for civilian sale after World War II, was a Super Deluxe Ford. It rolled off the assembly line on July 3, 1945.

As I have researched the infantry soldiers of World War II, my thought was that I was really thankful that my dad, Allen Spencer was not one of those men on the ground during the fighting. I felt bad for those men who were on the ground, fighting from the foxholes. I still do, because they were in constant danger. Bombs fall from the sky, and bullets fly from across the battlefield. If those things didn’t kill a soldier, the freezing cold, trench foot, or dysentery from the horribly unsanitary conditions could. It seemed that my dad’s situation was by far safer, but now, I’m not so sure that’s true.

As I have researched the infantry soldiers of World War II, my thought was that I was really thankful that my dad, Allen Spencer was not one of those men on the ground during the fighting. I felt bad for those men who were on the ground, fighting from the foxholes. I still do, because they were in constant danger. Bombs fall from the sky, and bullets fly from across the battlefield. If those things didn’t kill a soldier, the freezing cold, trench foot, or dysentery from the horribly unsanitary conditions could. It seemed that my dad’s situation was by far safer, but now, I’m not so sure that’s true.

The book I had been listening to, that took in World War II from D-Day to The Battle of the Bulge, talked mostly about the ground war, but then at the end, the reader said something that really struck me. It was about the look that crossed the face of a bomber crew’s faces before certain missions…those that would inevitably find the plane flying through flak. The look was one of fear. I knew flak was dangerous, but somehow I didn’t really connect flak with bringing down a plane, or seriously injuring its occupants. Nevertheless, it is quite dangerous for them.

As I researched the dangers of flak, a shocking revelation made itself known. I had written a story about the life expectancy of the ball turret gunner. My findings were that that life expectancy was about 12 seconds. That may be true when one is talking about the prospect of being shot, but when it comes to flak, that cannot be said. Apparently, where flak is concerned, the best place to be is in the plexiglass structure of the ball turret. Plexiglass holds up better against flak than other areas of the plane, so the ball turret gunner is much more protected…at least from flak. The same cannot be said for the bullets flying through the area. I was thankful that my dad was not a ball turret gunner, and that he only filled in as a waist gunner periodically. The waist gunners were in the open, where protection from bullets, and from flak was minimal…at best, non-existent at worst. I can’t imagine how those memories must have affected my dad, but in the book I listened to, the main reason many of the men didn’t want to talk about their experiences in World War II, or any war, was because talking about it brought those memories flooding in again.

After researching flak, and how it works, I can see why the men would get a look of fear on their faces as they prepared to go through areas anti-aircraft weapons shooting flak into the air. Some men said that they could see the red hot glow in the center of the flak, if it was very close. That tells me that it was like a small explosive devise. No wonder it could bring so much damage to a plane. I had known that flak could put holes in the fuselage, but somehow I hadn’t tied that with bringing down a plane. I surmise that it was the B-17

bomber top turret gunner’s daughter in me that wouldn’t allow me to place that danger around my dad. I didn’t want to think about the dangers of his every mission in World War II. My mind seems to have placed his plane in a bubble or a force field, so that no danger could come near him. I think every veteran wonders why they were spared, when others didn’t make it back home. I don’t think anyone can answer that question. As a Christian, I have to credit God for bringing my future dad home.

bomber top turret gunner’s daughter in me that wouldn’t allow me to place that danger around my dad. I didn’t want to think about the dangers of his every mission in World War II. My mind seems to have placed his plane in a bubble or a force field, so that no danger could come near him. I think every veteran wonders why they were spared, when others didn’t make it back home. I don’t think anyone can answer that question. As a Christian, I have to credit God for bringing my future dad home.

On July 19, 1989, in the skies over Alta, Iowa, United Airlines Flight 232, on which my great aunt, Gladys Cooper was a passenger, began the fateful journey to a catastrophic end. At 3:16pm, the rear engine’s fan disk broke apart due to a previously undetected metallurgical defect located in a critical area of the titanium-alloy. Basically that meant that the fan disk shattered, sending shrapnel through the hydraulic lines of all three independent hydraulic systems on board the aircraft. This horrific event caused the rapid loss of all the hydraulic fluid. The subsequent catastrophic disintegration of the disk had resulted in a spray of debris with energy levels that exceeded the level of protection provided by design features of the hydraulic systems that operate the DC-10’s flight controls. The flight crew lost its ability to operate nearly all of them. In the resulting crash landing, the right wing just tapped the runway, causing the plane to cartwheel and break apart as it went careening down the runway and into a corn field. While my Great Aunt Gladys was killed in the crash, the skill of the pilot and flight crew saved 185 lives, including their own.

On July 19, 1989, in the skies over Alta, Iowa, United Airlines Flight 232, on which my great aunt, Gladys Cooper was a passenger, began the fateful journey to a catastrophic end. At 3:16pm, the rear engine’s fan disk broke apart due to a previously undetected metallurgical defect located in a critical area of the titanium-alloy. Basically that meant that the fan disk shattered, sending shrapnel through the hydraulic lines of all three independent hydraulic systems on board the aircraft. This horrific event caused the rapid loss of all the hydraulic fluid. The subsequent catastrophic disintegration of the disk had resulted in a spray of debris with energy levels that exceeded the level of protection provided by design features of the hydraulic systems that operate the DC-10’s flight controls. The flight crew lost its ability to operate nearly all of them. In the resulting crash landing, the right wing just tapped the runway, causing the plane to cartwheel and break apart as it went careening down the runway and into a corn field. While my Great Aunt Gladys was killed in the crash, the skill of the pilot and flight crew saved 185 lives, including their own.

While listening to an audio book about World War II, and what happens when bombers flew through flak (Fl(ieger)a(bwehr)k(anone)). I knew that on at least one occasion, my dad, Allen Spencer, a Flight Engineer and Top Turret Gunner on a B-17 in World War II, was tasked with the job of cranking down the landing gear for landing. I don’t know what I had been thinking happened to the landing gear, maybe a close bit of flak the bent something in the gear perhaps, but what had not occurred to me was a catastrophic hit of that flak, causing all hydraulics to be lost. Nevertheless, quite likely that is what happened. It was one of the scenarios discussed in the book. As the hydraulics were lost, the red fluid was all over the floor of the aircraft, and the next thing that was required was to crank down the landing gear, because the gear could not be lowered without hydraulic fluid. Somehow, Dad’s precarious position of hanging out in the open bomb bay doors seemed like such a simple solution to the problem, albeit a heroic act, but the loss of hydraulics could have meant death to the crew. Getting the landing gear down was only part of the problem. What about the flaps, brakes, and such. These planes were in a really bad way.

Of course, my dad’s plane did land safely, given that he became my dad, but years later, when my mother, Collene Spencer’s Aunt Gladys was on a plane crippled by the loss of all hydraulics, I now realize…finally, that when my dad heard about what happened with Flight 232, as we all eventually did, he understood full well,

what the flight crew had been faced with. Something I only understood from the view of a spectator…for lack of a better word. He had been there. The Flight 232 situation quite likely took my dad back some 45 years to that day when he had to crank down the landing gear on a B-17 Bomber that had been damaged by flak, probably spilling hydraulic fluid all over the floor where the crew was standing. The experience must have been awful to go through, and the thought of what happened to Flight 232, almost as bad. And yet, in typical World War II veteran style, Dad said nothing, but rather set about comforting his family over the loss.

what the flight crew had been faced with. Something I only understood from the view of a spectator…for lack of a better word. He had been there. The Flight 232 situation quite likely took my dad back some 45 years to that day when he had to crank down the landing gear on a B-17 Bomber that had been damaged by flak, probably spilling hydraulic fluid all over the floor where the crew was standing. The experience must have been awful to go through, and the thought of what happened to Flight 232, almost as bad. And yet, in typical World War II veteran style, Dad said nothing, but rather set about comforting his family over the loss.

Sometimes we see a picture that looks so far-fetched that we assume that we are looking at a picture that has been photoshopped, and sometimes we are. Nevertheless, some pictures, unbelievable as they may seem, are the real deal. A while back, I stumbled upon an unbelievable photo of a plane crash, or rather the moment before the plane crashed. I was instantly intrigued. Could this be real? Or was it just a big ruse?

Sometimes we see a picture that looks so far-fetched that we assume that we are looking at a picture that has been photoshopped, and sometimes we are. Nevertheless, some pictures, unbelievable as they may seem, are the real deal. A while back, I stumbled upon an unbelievable photo of a plane crash, or rather the moment before the plane crashed. I was instantly intrigued. Could this be real? Or was it just a big ruse?

At the end of World War II, the English Electric Aviation Company received a contract to develop a jet bomber. The resulting bomber was the English Electric Lightning F1. The ER103 design study was sufficiently impressive for English Electric to be awarded the contract for two prototypes and a structural-test airframe. The early prototypes evolved into the Lightning, an airplane which was to span the time from when the Spitfire was our primary front-line fighter to the end of the Cold War. The Lightning was the only British designed and built fighter capable of speeds in excess of Mach 2 to serve with the Royal Air Force. The aircraft in the photograph was XG332. It was built in 1959, one of 20 pre-production Lightnings. Alan Sinfield took a photograph of XG332 in 1960 at Farnborough. However, it was the very last photograph taken of XG332, in 1962, that became the famous one, and deservedly so. How does someone manage to take a photograph like this? Jim Meads is the man who took the picture, but this was not the picture he expected to take that day. He was a professional photographer who lived near the airfield. In fact, he lived next door to de Havilland test pilot Bob Sowray.

Meads says that Bob Sowray mentioned that he was going to fly the Lightning that day. An excited Meads took his kids for a walk, taking his camera along, hoping to get a shot of the plane, and give his kids something amazing to remember. Well, that part of the walk went according to plan. It was a walk his kids would not soon forget. He had planned to take a photograph of the children with the airfield in the background, just as the Lightning came in to land. They found a good view of the final approach path and waited for the Lightning to return. As it turned out, Bob Sowray didn’t fly the Lightning that day. The pilot was George Aird, another test pilot working for De Havilland. George Aird was involved in the Red Top Air-to-Air Missile program. He was a well-respected test pilot.

The flight was to take place on September 19, 1962. The day did not go as planned in any way. George Aird was in the Lightning doing a demonstration flight off of the south coast. As he approached Hatfield from the north east, he realized that he had trouble. During the flight there was a fire in the aircraft’s reheat zone. “Un-burnt fuel in the rear fuselage had been ignited by a small crack in the jet pipe and had weakened the tailplane actuator anchorage. This weakened the tailplane control system which failed with the aircraft at 100 feet on final approach.” The plane suddenly pitched up, quite violently…just as Aird was coming in to land. Aird lost control of the aircraft and ejected. Had the nose of the plane not pitched up suddenly, Aird would not have had enough time to eject.

The tractor in the photograph was a Fordson Super Major. Upon close inspection of the grill, one can see that it reads D H Goblin, which is the name of another de Havilland jet engine…the Goblin. The tractor driver was 15-year-old Mick Sutterby, who spent that summer working on the airfield. He would play an amazing, but unexpected part in the amazing picture. He wasn’t posing for the camera, but rather, was telling the photographer, Jim Mead, to move on, because he shouldn’t be there. Mead saw the plane coming in and the nose pitch up. Then Aird ejected and Mead says he had just enough time to line up the shot as the Lightning came down nose first.

Sutterby recalls, “I followed my father into work at de Havilland, Hatfield in 1954 when I was 15. My father was the foreman in charge of the aerodrome and gardens. My job in the summer was gang-mowing the airfield and at the time of the crash in 1962 the grass had stopped growing and we were trimming round the ‘overshoot’ of the runway with a ‘side-mower’. I stopped to talk to a chap with a camera who was walking up a ditch to the overshoot. I stopped to tell him that he shouldn’t be here, I heard a roar and turned round and he took the picture! He turned out to be a friend of the pilot and had walked up the ditch to photograph his friend in the Lightning. I saw some bits fly off the plane before it crashed, but it was the photographer who told me he had ejected. There was not a big explosion when it crashed, just a loud ‘whhooooof’.”

“I was about 200 yards from the crash scene. I saw men running out of the greenhouses and checking the scene of the crash. The works fire brigade were on the scene within a minute. Somewhere at home I have a picture of it burning. Although the picture shows it nose diving to the ground, in fact it was slowly turning over and it hit the ground upside down nose first. I was later told that if the pilot had ejected a split second later he would have ejected himself into the ground. I was very lucky. If I had known he was coming into land, I would have been positioned near the ILS (Instrument Landing System) aerial which was only 20 yards or so from the crash site! I believe the photographer had his photo restricted by the Air Ministry for – I think – about 3 months because the plane was secret,” Sutterby said, almost as if in thought.

“He then took it to the Daily Mail who said it was a fake. The photo was eventually published by the Daily  Mirror. From there it went round the world, and I remember seeing a copy in the RAF museum at Hendon. I recollect the photographer usually photographed hunting scenes for magazines like The Field. I recollect that the pilot broke his legs but really was very lucky. I hope this is interesting. All from memory,” finished Sutterby.

Mirror. From there it went round the world, and I remember seeing a copy in the RAF museum at Hendon. I recollect the photographer usually photographed hunting scenes for magazines like The Field. I recollect that the pilot broke his legs but really was very lucky. I hope this is interesting. All from memory,” finished Sutterby.

George Aird didn’t have an easy landing, and in fact, landed on a greenhouse and fell through the roof. The fall broke both of his legs, and he landed on the ground, unconscious. The water from the sprinkler system for the tomatoes woke him up and he reportedly said that his first thought was that he must be in heaven. In the end no one was killed, but the resulting picture by Jim Meads is nothing short of spectacular!!

Opinions vary as to who the worst generals of World War II were, and I can’t say where I stand on the issue, but after researching several of the battles fought, whether won or lost, I can see how people could make up their own minds on the issue. It must also be noted that even the worst general can have enough good men under him to bring success through multiple blunders on the part of the general. Then, the general is considered a war hero. It doesn’t always happen, but sometimes, it does.

Opinions vary as to who the worst generals of World War II were, and I can’t say where I stand on the issue, but after researching several of the battles fought, whether won or lost, I can see how people could make up their own minds on the issue. It must also be noted that even the worst general can have enough good men under him to bring success through multiple blunders on the part of the general. Then, the general is considered a war hero. It doesn’t always happen, but sometimes, it does.

On September 14, 1944, the US 1st Marine Division landed on the island of Peleliu, one of the Palau Islands in the Pacific. It was part of a larger operation to provide support for General Douglas MacArthur, who was preparing to invade the Philippines. The Palaus were part of the Caroline Islands. They were among the mandated islands taken from Germany and given to Japan as one of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles at the close of World War I. The US military was unfamiliar with the islands, and Admiral William Halsey had argued against Operation Stalemate, which included the Army invasion of Morotai in the Dutch East Indies. He believed that MacArthur would meet minimal resistance in the Philippines, making this operation unnecessary, especially given the risks involved.

General William Henry Rupertus was the commander of the 1st Marine Division when they attacked the Japanese-held island Peleliu. Rupertus mistakenly predicted that the island would fall within 4 days. With that in mind, he sent his troops ashore with minimal water supplies. The battle was a horror show that dragged on for nearly 75 days. The Marines thought they knew how to attack the island, but the Japanese were using some new, innovative tactics, and so the Marines were unprepared. Nevertheless, Rupertus stuck to his original plan, even as casualties mounted, even withdrawing tank support for a critical assault, mistakenly believing it wasn’t needed. It’s actions like this that make you wonder how he ever got to be a general, I guess the Marines agreed, because Rupertus was pulled from command and soon died of a heart attack. The 1st Marine Division was pulled out after a month of vicious combat. They were in such bad shape that the division didn’t fight again for six months.

The pre-invasion bombardment of Peleliu had somehow seemed important, at the time, but it proved to be of no real help. The Japanese defenders of the island were buried too deep in the jungle, and the target intelligence given the Americans was faulty. Upon landing, the Marines met little immediate resistance, but that was a maneuver to get them further onto the island. Shortly thereafter, Japanese machine guns opened fire, knocking out more than two dozen landing craft. Scores of Japanese tanks and troops immediately stormed upon the marines. The shocked 1st and 5th Marine regiments fought for their lives. Jungle caves seemingly exploded with Japanese soldiers. Within one week of the invasion, the Marines lost 4,000 men. By the time it was all over, that number would surpass 9,000. The Japanese lost more than 13,000 men. Flamethrowers and bombs finally subdued the island for the Americans, but in the end, it all proved pointless. MacArthur invaded the Philippines without need of Army or Marine protection from either Peleliu or Morotai.

While MacArthur has a reputation as one of the most innovative and courageous generals in US history, he also committed inexplicable blunders at multiple points in the war. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, MacArthur was ordered to carry out pre-war attack plans on Japanese bases, but he gave no reply. As a result, Japanese planes immediately attacked, wiping out his air force. His thinly spaced and poorly supplied US and Filipino forces crumbled, and he was ordered to evacuate Manila with his command staff. About 150,000 Allied troops had been killed, wounded, or captured. His bold conduct over the next four years gained him a justifiable reputation as a war hero, but he was also reckless, arrogant, and careerist. He saw his role as the occupational governor of Japan as a stepping-stone to running for president and pardoned Japanese war criminals involved in human experimentation. These are not things that a general in the United States military should be doing, and while he was considered a hero by some, there were many others who would seriously disagree.

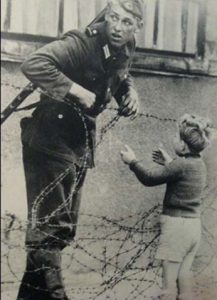

World War II took it’s toll on many people. The soldiers, families at home, and probably unknown to the people of the Allied nations…the German people. When we think of the Nazis, we think of an entire country so filled with hate for the Jewish people…as well as any nationality that was different that the Nazi white people. The reality is that while there were a relatively small number of Hitler’s puppets to actually embraced the thinking and the hatred of Hitler; there were also a great many of the German people who were not Nazis, nor did they agree with anything that Hitler did or believed. They were good and decent people, who valued life, and just wanted to work hard, and live their lives in peace and happiness.

World War II took it’s toll on many people. The soldiers, families at home, and probably unknown to the people of the Allied nations…the German people. When we think of the Nazis, we think of an entire country so filled with hate for the Jewish people…as well as any nationality that was different that the Nazi white people. The reality is that while there were a relatively small number of Hitler’s puppets to actually embraced the thinking and the hatred of Hitler; there were also a great many of the German people who were not Nazis, nor did they agree with anything that Hitler did or believed. They were good and decent people, who valued life, and just wanted to work hard, and live their lives in peace and happiness.

These post-war German citizens were faced with a new and strange kind of post-war reality. The country suffered from collective PTSD. Said one German citizen, “We were a broken, defeated, extinguished people in 1045. 60 million human beings suffered from PTDS. And Knowing that not only did you lose…but also that you were on the wrong side. On the wrong side of morality, of humanity, of history. We were the bad guys. There was no pride. Just the knowledge that we were at rock bottom, and rightfully so.”

As American and Allies, it is hard for us to accept their feelings of remorse. I’m sure that the Jews, Gypsies, and other persecuted races had an even harder time feeling bad for the German people…at least, not unless they were some of the German citizens who escaped from Germany along with other refugees, or those who helped their Jewish or Gypsy counterparts to escape or to survive. One of those sympathizers who lived, warned his children and grandchildren, saying, “Don’t forget, but don’t tell anyone about this.” He was so ashamed and so angry, still, 40, 50 years  later. He said that the Nazis had taken the best years of his life, saying, “We must look out for them, it can happen again. Beware, pay attention to politics! Speak up! We couldn’t stop them, maybe you can, next time.” The man hammered these things into his grandchild’s brain, over and over and over. He knew the dangers of complacency where politics is concerned. He knew that if they take your guns you are helpless. He knew that if evil people get in office, the danger grows exponentially. He had seen it…first hand. It is a lesson many people today need to learn. It could happen again, if we aren’t vigilant.

later. He said that the Nazis had taken the best years of his life, saying, “We must look out for them, it can happen again. Beware, pay attention to politics! Speak up! We couldn’t stop them, maybe you can, next time.” The man hammered these things into his grandchild’s brain, over and over and over. He knew the dangers of complacency where politics is concerned. He knew that if they take your guns you are helpless. He knew that if evil people get in office, the danger grows exponentially. He had seen it…first hand. It is a lesson many people today need to learn. It could happen again, if we aren’t vigilant.

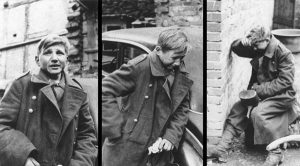

During World War II, if a man was a conscientious objector, things were…difficult. Things like that were not an automatic get out of the war card. Unless they had some necessary skill that would keep them stateside or in an office, they were signed up as a medic. Most of those men thought that was a good place for them, since the would be saving lives and not taking them, but I’m not sure who got it worse. The infantry or the medics.

During World War II, if a man was a conscientious objector, things were…difficult. Things like that were not an automatic get out of the war card. Unless they had some necessary skill that would keep them stateside or in an office, they were signed up as a medic. Most of those men thought that was a good place for them, since the would be saving lives and not taking them, but I’m not sure who got it worse. The infantry or the medics.

The men of the infantry usually considered the conscientious objectors to be cowards. That is not really the way a guy wanted to go into the army, but if they were seriously conscientious objectors, it was a calling they took seriously.  It was not, however, an easy job or the easy way out of combat. The difference between the infantrymen and the medics was that during combat, the infantrymen did their best to stay down, so the weren’t hit. The medics, on the other hand, ran into the fire to treat the wounded, and bring in the dead. It was no easy job.

It was not, however, an easy job or the easy way out of combat. The difference between the infantrymen and the medics was that during combat, the infantrymen did their best to stay down, so the weren’t hit. The medics, on the other hand, ran into the fire to treat the wounded, and bring in the dead. It was no easy job.

The medics, like most soldiers coming into the army were young men…boys really. They were often 18 or 19 years old. The infantrymen had plenty of names for them. None of them were nice…or complimentary, but the medics that stayed medics…the ones who ran into the fire to care for a wounded soldier were given new names. They were finally called medic…or more often Doc. And they were respected. They were also called hero, brave, courageous, and other respectful names. The  medics were not given the $10.00 per month extra that combat soldiers were given. That made the infantrymen furious. They collected money from each other to provide combat pay for their medics. The men refused to have their medics receive less.

medics were not given the $10.00 per month extra that combat soldiers were given. That made the infantrymen furious. They collected money from each other to provide combat pay for their medics. The men refused to have their medics receive less.

World War II saw eleven medics who received the Medal of Honor…as well as other medals. These men were wounded taking care of the men, and they were even killed saving the lives of the men in their care. These men were heroes, just like their counterparts in the infantry, and there isn’t an infantryman that ever fought, who would disagree.

Whether it was World War I or World War II, every flyer knew what a dogfight was. Dogfights were the undisputed, most intense type of aerial combat there was. Basically it was an intense game of chicken…one that no one really wanted to play. The fight for supremacy in the skies over Europe was vital to the war effort. The Axis of Evil nations had to be stopped, and the air war was going to be the way to win the war.

Whether it was World War I or World War II, every flyer knew what a dogfight was. Dogfights were the undisputed, most intense type of aerial combat there was. Basically it was an intense game of chicken…one that no one really wanted to play. The fight for supremacy in the skies over Europe was vital to the war effort. The Axis of Evil nations had to be stopped, and the air war was going to be the way to win the war.

After watching some of the cockpit footage of the dogfights, I don’t know how those pilots did it. In the non-war world, two planes going head to head is not an ideal situation, but that was what the fighter planes of war have to do. As one plane starts to gain dominance over another, the plane being chased often goes into a steep climb, followed by the pursuing plane. The first plane to stall is going to end up being chased, because as he loses power, he drops and then must run first to gain power and then to get away from his attacker. If you thought going head to head with another plane was scary, imagine a deliberate stall…for supremacy!! That just seems insane to me, but that is  the nature of the dogfight. These pilots had to be very brave. There is no way to fly like that, or especially fight like that unless you area very brave pilot…not to mention a skilled pilot. Without that skill, the pilots would not survive long enough to even become an ace.

the nature of the dogfight. These pilots had to be very brave. There is no way to fly like that, or especially fight like that unless you area very brave pilot…not to mention a skilled pilot. Without that skill, the pilots would not survive long enough to even become an ace.

For a fighter pilot to become an ace, he had to shoot down five enemy planes. A gunner could become an ace too, but the majority of aces are fighter pilots. The key to becoming an ace, besides shooting down the enemy, is obviously to stay alive long enough to become an ace. In these dogfights, that was difficult for sure.

After World War II, many of the veterans were hesitant to talk about their experiences. My dad, Allen Spencer was one of those men. We were never exactly sure why he didn’t talk about it, but thought that he didn’t want to brag. I don’t really think that was it at all.

After World War II, many of the veterans were hesitant to talk about their experiences. My dad, Allen Spencer was one of those men. We were never exactly sure why he didn’t talk about it, but thought that he didn’t want to brag. I don’t really think that was it at all.

While listening to an audiobook called Citizen Soldiers, which covers the D-Day battle and the Battle of the Bulge, it hit me…even before the author said it. The reason soldiers didn’t talk much about war was a deliberate effort to forget. Unfortunately for most of her them, forgetting was impossible. Their minds were filled with haunted memories. The book mostly covers the thoughts of the infantry, but touches on the air war too.

After listening to the author’s account of the battle, I don’t think I could ever forget either, and I wasn’t there. Memories of the 19 year old farm boy away from home for the first time, and not really trained for combat. When the shooting started, he stood up to fire. Other soldiers told him to get down, by it was too late. His first battle had become his last, as an enemy bullet pierced his forehead. The soldiers who witnessed it, felt sick to

their stomachs. It was a time when a seasoned veteran was just 22 years old…and he had been made an office when his commanding officer was killed. There weren’t very many of the older men left…and by older I mean 30.

their stomachs. It was a time when a seasoned veteran was just 22 years old…and he had been made an office when his commanding officer was killed. There weren’t very many of the older men left…and by older I mean 30.

There were memories of a young prisoner of war, packed into a train to the POW camps was singing in his beautiful tenor voice, all the Christmas music he could think of to help raise moral. It was working, but suddenly the trains were under attack. The prisoners couldn’t get out, and the guards had run away. Finally a skinny boy was able to get out through a tiny window. He opened the door to his car and the men moved to free the other prisoners. There was really nowhere to go, but they escaped the attack. Then, the guards came back and loaded them back on the train. When someone asked the tenor to sing some more, they were told that he hadn’t made it back. His sweet voice was forever silenced. The men on the train were silent too…sick at heart.

The fighters in the plane’s overhead knew that it was kill or be killed, but whenever a plane went down, enemy

or one of theirs, they counted the parachutes, hoping the men got out alive. For them non the planes dropping bombs, they knew that someone below went to work that day, having no idea tat they would not be returning home again. They had been simple factory workers, just doing what they were told. And what of the missed targets that landed bombs on schools and other civilian locations. The men in the planes above had to live with that. They had done their duty, but it certainly didn’t feel good.

or one of theirs, they counted the parachutes, hoping the men got out alive. For them non the planes dropping bombs, they knew that someone below went to work that day, having no idea tat they would not be returning home again. They had been simple factory workers, just doing what they were told. And what of the missed targets that landed bombs on schools and other civilian locations. The men in the planes above had to live with that. They had done their duty, but it certainly didn’t feel good.

I have long been interested in war, and especially World War II. Every aspect of it interests me, and I find myself wondering about the enemy. I’m sure that might seem odd to many people, but as we have found in the United States, just because the government goes to war, does not mean that every citizen, or even every soldier agrees with the reasons the country has gone to war. I have been listening to a couple of audiobooks that have taken in D-Day, and I came across something interesting.

I have long been interested in war, and especially World War II. Every aspect of it interests me, and I find myself wondering about the enemy. I’m sure that might seem odd to many people, but as we have found in the United States, just because the government goes to war, does not mean that every citizen, or even every soldier agrees with the reasons the country has gone to war. I have been listening to a couple of audiobooks that have taken in D-Day, and I came across something interesting.

Without going into all of that amazing strategy of warfare, I want to focus on one of the bombing maneuvers that took place. One of the soldiers on the ground was trying to take cover from incoming German bombs. After the bombing stopped, he looked out and was shocked to see eight bombs embedded in the ground near his foxhole. They had not gone off. He knew that it is possible for bombs to be duds, but he hadn’t heard of any American bombs that had turned out to be duds…especially eight of them at the same time, in the same place.  He wasn’t bragging on the American bombs, their craftmanship, or their ingenuity, but rather, wondering how so many German bombs could have been duds…all at the same time.

He wasn’t bragging on the American bombs, their craftmanship, or their ingenuity, but rather, wondering how so many German bombs could have been duds…all at the same time.

Then the soldier made an observation that I had not considered, but that fell right into my view that not everyone in Germany agreed with Hitler. The American bomb builders were doing their job willingly. They were working to make the bombs efficient, because Germany needed to be defeated. In contrast, the German bomb builders were actually Polish slaves. Hitler had invaded their nation and was forcing them to play a part in a war that they disagreed with. The soldier considered these things and came to the conclusion that somehow the Polish slaves had been able to build a bomb that they knew would not explode, but would still pass the inspections of the Germans. The soldier believed that eight unexploded bombs could not be coincidental. It had to be sabotage.

In my research, I have seen situations where the citizens have helped the enemy, at great risk to their own safety. I have seen situations where the citizens have given aid to the enemy. And this situation was a blatant sabotage of the weapons of warfare. Within their nations, these acts were acts of treason, but they were actually fighting the evil that had tried to take over their nation. Within their confines, they were standing up for their values…for good, and for what was right. They were the enemy, in location only, because in their hearts, the were fighting for what was right, and I have to respect them for that.