World War II

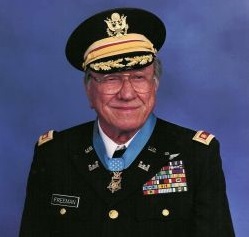

Ed Freeman first served in the military during World War II, in the United States Navy on the USS Cacapon (AO-52). While World War II was in no way uneventful or unimportant, it was not the most eventful part of Freeman’s service. Freeman decided to continue on in the military. Freeman had reached the rank of first sergeant by the time the Korean War began. By this time Freeman was in the Corps of Engineers, but his company fought as infantry soldiers in Korea. Freeman found himself fighting in the Battle of Pork Chop Hill, where he earned a battlefield commission as one of only 14 survivors out of 257 men who made it through the opening stages of the battle. His second lieutenant bars were pinned on by General James Van Fleet personally. He was given command of B Company and led them back up Pork Chop Hill.

Ed Freeman first served in the military during World War II, in the United States Navy on the USS Cacapon (AO-52). While World War II was in no way uneventful or unimportant, it was not the most eventful part of Freeman’s service. Freeman decided to continue on in the military. Freeman had reached the rank of first sergeant by the time the Korean War began. By this time Freeman was in the Corps of Engineers, but his company fought as infantry soldiers in Korea. Freeman found himself fighting in the Battle of Pork Chop Hill, where he earned a battlefield commission as one of only 14 survivors out of 257 men who made it through the opening stages of the battle. His second lieutenant bars were pinned on by General James Van Fleet personally. He was given command of B Company and led them back up Pork Chop Hill.

It was Freeman’s childhood dream to become a pilot, and his new commission made him eligible to become a pilot. Nevertheless, there was one drawback. When he applied for pilot training he was told that, at six feet four inches, he was “too tall” for pilot duty. That phrase stuck, and he became known as “Too Tall” for the rest of his career. It was a devastating setback, but in 1955, the height limit for pilots was raised and Freeman was finally accepted into flight school. He first flew fixed-wing army airplanes, but later switched to helicopters. When the Korean War ended, he flew the world on mapping missions.

By this time, Ed W. “Too Tall” Freeman had already had many success stories, but his real success story came during the Vietnam War, during the Battle of Ia Drang, specifically on November 14, 1965. During the battle, there were multiple men injured and the possibility of them dying was very real. Their unit was outnumbered 8-1 and the enemy fire on the men on the ground was so intense from 100 yards away, that the Commanding Officer ordered the MedEvac helicopters to stop coming in. That was basically a death sentence for the wounded men. The men were at LZ X-Ray, one of the most legendary war sites in Vietnam. It was here that the United States had its first major battle with the North Vietnamese People’s Army of Vietnam, the first very violent round of a bout that would last ten more years. There was really no way for the MedEvac helicopters to save them. Enter, Captain Ed Freeman, who was not a MedEvac pilot, by the way. Nevertheless, that did not stop him. He could not leave a man behind, much less 29 men. That this was not his job, meant nothing to Freeman, who heard the radio call and decided he was going to fly his Huey down into the machine gun fire anyway. He had not been given orders not to go, because he was not a MedEvac pilot, so he went. Those men soon knew that Captain Ed Freeman was coming in for them. Freeman dropped his Huey in and sat there in the machine gun fire, as they loaded 3 men at a time on board. Then, he flew up and out through the gunfire to get these men to the medical teams safety. And, he didn’t go in just once!! He kept going back…13 more times!! He went in until all the wounded were out. No one knew until the mission was over that the Captain had been hit 4 times in the legs and left arm.

Ed “Too Tall” Freeman was born on November 20, 1927 in Neely, Mississippi, the sixth of nine children. At the age of 13, he saw thousands of men on maneuvers pass by his home in Mississippi. He knew then that he wanted to become a soldier. Freeman grew up in nearby McLain, Mississippi, and graduated from Washington High School, however, at age 17, before graduating from high school, Freeman served in the United States Navy for two years. He then returned to his hometown and graduated from high school after the war. He joined the United States Army in September 1948, and married Barbara Morgan on April 30, 1955. They had two sons. Mike was born in 1956, and Doug was born in 1962.

Freeman’s commanding officer nominated him for the Medal of Honor for his actions at Ia Drang on November 14, 1965. Unfortunately, not in time to meet a two-year deadline in place at that time. He was instead awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The Medal of Honor nomination was disregarded until 1995, when the two-year

deadline was removed. He was finally and formally presented with the medal on July 16, 2001, in the East Room of the White House by President George W. Bush. Freeman died on August 20, 2008, due to complications from Parkinson’s disease. He was buried with full military honors at the Idaho State Veterans Cemetery in Boise.

deadline was removed. He was finally and formally presented with the medal on July 16, 2001, in the East Room of the White House by President George W. Bush. Freeman died on August 20, 2008, due to complications from Parkinson’s disease. He was buried with full military honors at the Idaho State Veterans Cemetery in Boise.

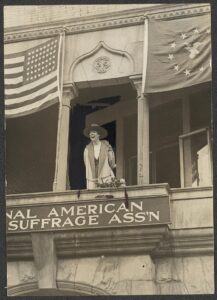

The 19th Amendment states that the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” In theory, this language guaranteed that all women in the United States could not be prevented from voting because of their gender. Of course, these days, no one really gives that a second thought, because…well, of course, women can vote. Who dared to think otherwise? Nevertheless, women were not always given the right to vote. In fact, for many years, men thought that politics was something that women could not possible begin to understand, and that it was a subject that was simply too harsh for the fragile female mind. Hahahaha!! We can laugh at such a thought now, because it is completely absurd, but that is what everyone thought back then…before the 19th Amendment was passed, following a fierce battle between the women suffragists and the men who ruled the nation.

The 19th Amendment states that the right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” In theory, this language guaranteed that all women in the United States could not be prevented from voting because of their gender. Of course, these days, no one really gives that a second thought, because…well, of course, women can vote. Who dared to think otherwise? Nevertheless, women were not always given the right to vote. In fact, for many years, men thought that politics was something that women could not possible begin to understand, and that it was a subject that was simply too harsh for the fragile female mind. Hahahaha!! We can laugh at such a thought now, because it is completely absurd, but that is what everyone thought back then…before the 19th Amendment was passed, following a fierce battle between the women suffragists and the men who ruled the nation.

Nevertheless, in the midst of that fierce battle for the right to vote, an odd event took place in the form of the election of a US Congress member, Jeanette Rankin somehow being elected to Congress!! She was elected to  the US House of Representatives as a Republican from Montana in 1916, and again in 1940. Rankin was a woman, so how could this have possibly happened. She couldn’t even vote, and yet she won the election. That’s crazy. If her “fragile” mind could not be expected to understand how to vote for the office, how would she ever be able to function in the office. I mean, after all, she would be dealing with the same politics that her fellow members of congress had deemed her too fragile to understand. In fact, Jeanette Rankin would not be able to vote in an election until August 18, 1820. Her term in office ran from March 4, 1917 to March 3, 1919…during which time she was the only woman in the United States who could vote. Rankin would serve again from January 3, 1941 to January 3, 1943. Oddly, each of Rankin’s Congressional terms coincided with initiation of US military intervention in the two World Wars. A lifelong pacifist, she was one of 50 House members who opposed the declaration of war on Germany in 1917. In 1941, she was the only member of Congress to vote against the declaration of war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

the US House of Representatives as a Republican from Montana in 1916, and again in 1940. Rankin was a woman, so how could this have possibly happened. She couldn’t even vote, and yet she won the election. That’s crazy. If her “fragile” mind could not be expected to understand how to vote for the office, how would she ever be able to function in the office. I mean, after all, she would be dealing with the same politics that her fellow members of congress had deemed her too fragile to understand. In fact, Jeanette Rankin would not be able to vote in an election until August 18, 1820. Her term in office ran from March 4, 1917 to March 3, 1919…during which time she was the only woman in the United States who could vote. Rankin would serve again from January 3, 1941 to January 3, 1943. Oddly, each of Rankin’s Congressional terms coincided with initiation of US military intervention in the two World Wars. A lifelong pacifist, she was one of 50 House members who opposed the declaration of war on Germany in 1917. In 1941, she was the only member of Congress to vote against the declaration of war on Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Jeanette Rankin was born on June 11, 1880, near Missoula in Montana Territory. Montana would not become a  state for another nine years. Her parents were, schoolteacher Olive (née Pickering) and Scottish-Canadian immigrant John Rankin, a wealthy mill owner. She was the eldest of seven children, including five sisters (one of whom died in childhood), and a brother, Wellington, who became Montana’s attorney general, and later a Montana Supreme Court justice. One of her sisters, Edna Rankin McKinnon, became the first Montana-born woman to pass the bar exam in Montana and was an early social activist for access to birth control. With all that, it’s little wonder that she became a congresswoman. Apparently, politics ran in the family, and was likely an often-debated subject in the family home.

state for another nine years. Her parents were, schoolteacher Olive (née Pickering) and Scottish-Canadian immigrant John Rankin, a wealthy mill owner. She was the eldest of seven children, including five sisters (one of whom died in childhood), and a brother, Wellington, who became Montana’s attorney general, and later a Montana Supreme Court justice. One of her sisters, Edna Rankin McKinnon, became the first Montana-born woman to pass the bar exam in Montana and was an early social activist for access to birth control. With all that, it’s little wonder that she became a congresswoman. Apparently, politics ran in the family, and was likely an often-debated subject in the family home.

While Rankin was in her first term in office, it would seem to me that she must have felt a very strong sense of responsibility, because she was at that time the voice of all women…at least as it applied to government and politics. I can’t say that I would have agreed with all of her votes in office, especially where it applied to the two world wars, which I feel the United States needed to be involved in. Perhaps it is that aspect of being in office that the men didn’t think women were very well equipped to handle…war being such an emotional issue and all. I still think that there are many women who might struggle with the idea of sending our men into war, but then there are men who feel the same way, so I guess it is just a matter of where people stand concerning war. To date, Rankin remains the only woman ever elected to Congress from Montana.

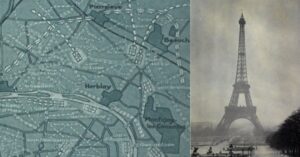

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

London’s Daily Telegraph explains that the fake city wasn’t just “a bunch of cardboard cutouts.” No, far from it, in fact. There were “electric lights, replica buildings, and even a copy of the Gare du Nord—the station from which high-speed trains now travel to and from London.” The painters went so far as to use paint to create “the impression of dirty glass roofs of factories.” Fake trains and railroad tracks were lit up as well. There was a phony Champs-Elysées. Many of us today would say, “How could that work? The Germans must have known where they were dropping their bombs!” Nevertheless, it stands to reason that in the early 20th century, the plan could have worked. “Radar was in its infancy in 1918, and the long-range Gotha heavy bombers being used by the German Imperial Air Force were similarly primitive,” the Telegraph notes. “Their crew would hold bombs by the fins and then drop them on any target they could see during quick sorties over major cities like Paris and London.”

No one really knows how well the plan might have worked, because it was never put to the test. World War I ended before the fake city was finished. Both the real Paris and the fake one escaped significant damage. The fake version has long since been dismantled, though photos of it still remain. I suppose it was a ghost town of  it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

To further validate the idea, French fighter pilots reported that during night flights they looked for familiar features of the landscape below when attempting to locate Paris. According to their research, railways, lakes, rivers, roads and woodland were the most useful indicators that they were in the neighborhood. Using this information, the mastermind behind the replica project, Fernand Jacopozzi, along with his team of highly capable engineers worked to make life even harder for the German pilots who were already struggling to find their bearings in an era before radar or precision targeting. Intending to confuse an enemy pilot sufficiently that he would start to doubt his own bearings, the construction of Paris’ mirror image began in earnest at Villepinte to the northeast where a working model of the Gare de l’Est gradually began to take form.

The “fake Paris” was exquisite. No detail was overlooked: “complex, sprawling networks of lights arranged skillfully creating the impression of railway tracks and avenues, as well as storm lamps clustered together on ingenious moving platforms designed to simulate vast steam trains in motion. Immense empty sheds masquerading as factories had translucent sheets of painted canvas stretched tightly across their wooden frames which were illuminated from underneath, an arrangement that to anyone passing overhead would look remarkably like the dirty glass roofs characteristic of industrial buildings. Working furnaces were also installed to add an extra dimension of reality and the factory’s lights were even configured to dim noticeably during an air raid, fooling enemy pilots into believing that the facsimile buildings were, in fact, occupied.”

Because World War I ended, it was only this small part of Zone A that was built. The German bombing campaign came to an end in September 1918 and the armistice was signed at Compiègne two months later. The mock factories and railway network at Villepinte were dismantled shortly after the hostilities ceased. By the beginning of the 1920s little remained of the project. Though his fascinating idea never really got much further than the drawing board, the designs of Fernand Jacopozzi inspired similarly ambitious plans in the United States during World War II.

While riding the 1880 Train on the last day of our annual trip to the Black Hills, Bob and I were sitting back, relaxing and enjoying the ride. It is a favorite part of our trip each year. One of the things that I like to do on these train rides, is to listen to what the people around us think of the journey. When you ride the train every year. You know the area, and while it is still very interesting to me, I do know the area. Others don’t, so it’s interesting to see what they think of this area I love so much. I almost feel like a local listening to the tourists who are viewing this place for the first time.

While riding the 1880 Train on the last day of our annual trip to the Black Hills, Bob and I were sitting back, relaxing and enjoying the ride. It is a favorite part of our trip each year. One of the things that I like to do on these train rides, is to listen to what the people around us think of the journey. When you ride the train every year. You know the area, and while it is still very interesting to me, I do know the area. Others don’t, so it’s interesting to see what they think of this area I love so much. I almost feel like a local listening to the tourists who are viewing this place for the first time.

This trip’s most profound conversation was a little different, and it really made me think. The train has a recorded narrative, and a little boy, about 5 or 6 years old was listening to it. So often, children don’t really listen to such things, but this little boy was rather intently listening to the message. So as he listened, the narrator said that

the train was in use during World War I and World War II, and the boy said, “What’s a war?” That really made me wonder…how nice it would be, not to know what war is. Yes, there have been wars in his lifetime, and indeed, we are in one even now, but this little boy is too young to really fathom the meaning of the word…war. He still possessed an innocence when it comes to war, killing, and death. That innocence is about to end, I suppose, because once his aunt or mother answered his question, he will forever know what a war is. He cannot go back to that innocence again. It is gone.

the train was in use during World War I and World War II, and the boy said, “What’s a war?” That really made me wonder…how nice it would be, not to know what war is. Yes, there have been wars in his lifetime, and indeed, we are in one even now, but this little boy is too young to really fathom the meaning of the word…war. He still possessed an innocence when it comes to war, killing, and death. That innocence is about to end, I suppose, because once his aunt or mother answered his question, he will forever know what a war is. He cannot go back to that innocence again. It is gone.

I came away from that experience a little sad. Children have such an innocent joy, and for this boy, that is changing. True…he won’t fully lose that innocence in one explanation, and it will depend on how much the

adults with him can soften the truth for him, but no matter what we do or say, war and death go together, and death by war is not pretty. This boy has an imagination, and if he continues to question the adults in his life, he will begin to get a clear picture of war, and what it really is. Then, as he grows, that picture will become more and more vivid. He will know what death by war means. War is a part of life, and eventually we all know what war means, but for me, the question felt sad, because I was witnessing the beginning of the end of his innocence. It’s a moment I wont easily forget either.

adults with him can soften the truth for him, but no matter what we do or say, war and death go together, and death by war is not pretty. This boy has an imagination, and if he continues to question the adults in his life, he will begin to get a clear picture of war, and what it really is. Then, as he grows, that picture will become more and more vivid. He will know what death by war means. War is a part of life, and eventually we all know what war means, but for me, the question felt sad, because I was witnessing the beginning of the end of his innocence. It’s a moment I wont easily forget either.

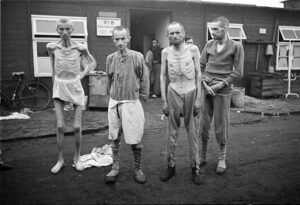

Using prisoners-of-war as free labor in the concentration camps was not an unheard of practice during World War II. Many of the prisoners in Auschwitz were forced to do administrative and labor duties, such as sorting new arrivals’ possessions, constructing and expanding the camps, and taking photos of the other captives. In the photo lab at Auschwitz alone, nearly 39,000 prison photographs were taken. The problem with those photos was that when the Nazis began to realize that they were going to lose the war, they knew that all those photos were proof positive of their guilt in the matter of the Holocaust. That meant that the photos had to be destroyed.

Using prisoners-of-war as free labor in the concentration camps was not an unheard of practice during World War II. Many of the prisoners in Auschwitz were forced to do administrative and labor duties, such as sorting new arrivals’ possessions, constructing and expanding the camps, and taking photos of the other captives. In the photo lab at Auschwitz alone, nearly 39,000 prison photographs were taken. The problem with those photos was that when the Nazis began to realize that they were going to lose the war, they knew that all those photos were proof positive of their guilt in the matter of the Holocaust. That meant that the photos had to be destroyed.

During the evacuation of Auschwitz in 1945, photo lab workers Wilhelm Brasse and Bronislaw Jureczek were ordered to burn all photographic evidence. The men knew that to do so would mean that the Nazis would get away with the heinous murders they had committed. So, they came up with a way to save the pictures. They placed wet photo paper at the bottom of the furnace before placing the real pictures inside. With the furnace so packed and the wet paper creating so much smoke, the blaze went out quickly. Then, once they were unsupervised, the men were able to take the unharmed pictures from the furnace to smuggle them out. The precious pictures of victims of the Holocaust were then cataloged, and have been kept in the Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

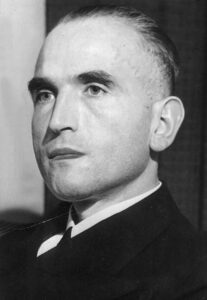

On July 11, 1944, evidence of mass murder of Jews at the extermination camp was provided to Winston Churchill by four escapees from Auschwitz. For two years, the Nazis had managed to keep the gas chambers in Auschwitz, southern Poland, a secret. Churchill wrote to his Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, “There is no doubt this is probably the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed in the whole history of the world…all concerned in this crime who may fall into our hands, including people who only obeyed orders by carrying out the butcheries, should be put to death.”

Auschwitz was the principal Nazi extermination camp in World War II. The complex covered at least 15 square miles. As World War II was coming to a close, and the Nazis were fleeing their own demise, the camp was evacuated, there were about 67,000 inmates who were still alive there. About 56,000 of these are led away. The rest were too sick to move, so they were left behind to die. As many as 250,000 people will die on the roads before the end of the war. Originally, the site for Auschwitz was chosen because the main railway lines from Germany and Poland passed through the area. By taking the prisoners to Poland, the Nazis hoped to keep their existence a secret. When the prisoners were sent to Auschwitz, they actually had to pay their own way…to be stuffed into a cattle car, so tightly that they couldn’t even fall down if they passed out or died. Prisoners deported to Auschwitz went there to die. The Nazis had no plans for them to survive. Auschwitz contained five crematoria, made and patented by German engineering company Töpf and Sons. It was estimated that they could dispose of 4,756 corpses a day. The crimes against humanity that had been committed here were atrocious, and panic had set in among the SS guards, who feared for their lives at the hands of the ruthless Red Army when it arrived.

For the prisoners, the end was also in sight, either by death, or by liberation for the few survivors of one of humanity’s most vile atrocities. The snow across the grounds of Auschwitz was deep, and temperatures are well below freezing. The Soviet Red Army was only a few miles away. Many SS officers and their families had already left, with cases full of valuables stolen from murdered inmates. Those on the death marches from Auschwitz survived by eating the snow on the shoulders of the people in front of them, because if they bent down to pick up the slush they risked being shot. As the prisoners marched slowly west through Poland, SS Lieutenant Colonel Rudolf Höss was heading in the opposite direction. Höss had been given the task of building Auschwitz by Himmler and had been the camp’s brutal commandant, living in luxury with his wife and five children just 100 yards from the camp grounds. After consideration, he headed back to Auschwitz, past what he described as “stumbling columns of corpses,” to make sure all evidence linking him to the genocide had been destroyed. But Höss was forced to turn his car around as the Russians advanced toward him. In 1946, he was captured and a year later hanged at Auschwitz.

Inmates, Brasse and Jureczek employed at Auschwitz’s Identification Service saved the thousands of negatives

of prisoners’ ID photographs, at great personal risk to themselves, and because they did, at least some of the guilty ones could be held accountable. The photos were intended to be a way to identify prisoners if they escaped, but their rapid starvation made these images useless. Nevertheless, Brasse and Jureczek were keen on preserving evidence of the atrocities at Auschwitz, and in the end, their efforts paid off.

of prisoners’ ID photographs, at great personal risk to themselves, and because they did, at least some of the guilty ones could be held accountable. The photos were intended to be a way to identify prisoners if they escaped, but their rapid starvation made these images useless. Nevertheless, Brasse and Jureczek were keen on preserving evidence of the atrocities at Auschwitz, and in the end, their efforts paid off.

How could a food become a problem in a war? I mean its something you eat, not fight with. Nevertheless, during World War I, the Germans were so hated and the Third Reich was so evil, that no one among the Allies wanted anything to do with them. They didn’t even want to be associated with anything that even remotely sounded like it was German. With that in mind, the word “hamburger” came to mind. It was decided that the “hamburger” was just a little too German to be allowed to continue being served with that name. You might think that people would get mad about that, but the people were very loyal to our nation and to the cause. They couldn’t tolerate the horrific crimes against humanity they saw in front of themselves. The Germans made it very clear to the world that they were, at least will Hitler was in charge, the most horrific nation on Earth.

How could a food become a problem in a war? I mean its something you eat, not fight with. Nevertheless, during World War I, the Germans were so hated and the Third Reich was so evil, that no one among the Allies wanted anything to do with them. They didn’t even want to be associated with anything that even remotely sounded like it was German. With that in mind, the word “hamburger” came to mind. It was decided that the “hamburger” was just a little too German to be allowed to continue being served with that name. You might think that people would get mad about that, but the people were very loyal to our nation and to the cause. They couldn’t tolerate the horrific crimes against humanity they saw in front of themselves. The Germans made it very clear to the world that they were, at least will Hitler was in charge, the most horrific nation on Earth.

Because of the conflict between Germany and the rest of the world, menus were changed to purge the names of German foods from restaurant menus. The name sauerkraut became “liberty cabbage,” and hamburgers became “liberty steaks.” Frankfurters, a very German name, was also deemed unacceptable during World War I, and in some places the name was switched to “liberty sausages,” but that was one new name that didn’t quite stick…especially when someone tried the term “hot dog.” It seems almost laughable now, because why should food play such a big part in the feelings of people, but then again, in this day and age, we are facing a situation that is much the same…the current “war” against China, Italy, and Germany (once again). This war may not be one  of dropping bombs and killing people, but it is a war nevertheless…and it is just as dangerous, if not more so.

of dropping bombs and killing people, but it is a war nevertheless…and it is just as dangerous, if not more so.

After World War II, and after the disdain against the Germans faded, the hamburger reemerged. During that time, the invention claims also emerged. It is thought that the hamburger was invented between 1885 and 1904, but it is clearly the product of the early 20th century. The origin is under dispute. Some say it was invented in the United States and some say that it was invented in Germany. During the following 100 years, the hamburger spread throughout the world, and continued on until World War I when it became just a little too German.

Sometimes, in researching weapons of war, and especially during World War II, I am shocked and horribly saddened by the ability of man to impose new and horrific means of death upon their enemies…simply because they disagree about how things should be run. During World War II, and possibly earlier, the killing method of Carpet bombing, also known as saturation bombing, came into practice. Carpet bombing is just what you would expect, “a large area bombardment done in a progressive manner to inflict damage in every part of a selected area of land.” Instantly, a picture of multiple explosions, the destruction of large areas of a town, or the entire town, come to mind. Mass casualties are expected. This is the way war is waged when hate reigns, but then most wars these days or even in the World War II era were filled with hate.

Sometimes, in researching weapons of war, and especially during World War II, I am shocked and horribly saddened by the ability of man to impose new and horrific means of death upon their enemies…simply because they disagree about how things should be run. During World War II, and possibly earlier, the killing method of Carpet bombing, also known as saturation bombing, came into practice. Carpet bombing is just what you would expect, “a large area bombardment done in a progressive manner to inflict damage in every part of a selected area of land.” Instantly, a picture of multiple explosions, the destruction of large areas of a town, or the entire town, come to mind. Mass casualties are expected. This is the way war is waged when hate reigns, but then most wars these days or even in the World War II era were filled with hate.

In the European Theatre, the first city to suffer heavily from aerial bombardment was Warsaw, on September 25, 1939. Achieving the results they wanted, the Germans continued this trend in warfare with the Rotterdam Blitz…an aerial bombardment of Rotterdam by 90 bombers of the German Air Force on May 14, 1940, during the German invasion of the Netherlands. The objective was to support the German assault on the city, break Dutch resistance, and force the Dutch to surrender. So in the middle of a ceasefire, they dropped the bombs anyway, destroying almost the entire historic city center, killing nearly nine hundred civilians and leaving 30,000 people homeless. That was still not enough for the Nazis. The Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL) used the destructive success of the bombing to threaten to destroy the city of Utrecht, if the Dutch government did not surrender. The Dutch surrendered early the next morning.

With the actions of the Nazis, the British knew that they had to act. The Battle of Britain developed from a fight for air supremacy into the strategic and aerial bombing of London, Coventry and other British cities. The British built up the RAF Bomber Command in retaliation for the bombings, which was capable of delivering many thousands of tons of bombs onto a single target, in spite of heavy initial bomber casualties in 1940. The plan was to break German morale and obtain the surrender which Douhet had predicted 15 years earlier. Then the  United States joined the war and the USAAF greatly reinforced the campaign, bringing in the Eighth Air Force into the European Theatre.

United States joined the war and the USAAF greatly reinforced the campaign, bringing in the Eighth Air Force into the European Theatre.

Still, that meant that the Allies would have to play the same game the Nazis had played. Many cities, both large and small, were virtually destroyed by Allied bombing. Cologne, Berlin, Hamburg and Dresden are among the most infamous, the latter two developing firestorms. I suppose the Germans finally found out what their own horrific tactics had done. Carpet bombing was also used as close air support (as “flying artillery”) for ground operations. The massive bombing was concentrated in a narrow and shallow area of the front (a few kilometers by a few hundred meters deep), closely coordinated with the advance of friendly troops. The first successful use of the technique was on May 6, 1943, at the end of the Tunisia Campaign. Carried out under Sir Arthur Tedder, it was hailed by the press as Tedder’s bomb-carpet (or Tedder’s carpet). The bombing was concentrated in a four by three-mile area, preparing the way for the First Army. This tactic was later used in many cases in the Normandy Campaign.

Carpet bombing was used extensively against Japanese civilian population centers, such as Tokyo, in the Pacific War. On the night of March, 9-10, 1945, 334 B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers were directed to attack the most heavily populated civilian sectors of Tokyo. Over 100,000 people burned to death in just one night from a heavy bombardment of incendiary bombs, comparable to the wartime number of US casualties in the entire Pacific theater. Another 100,000 to one million Japanese were left homeless. Similar attacks against Kobe, Osaka, and Nagoya, as well as other sectors of Tokyo followed, where over 9,373 tons of incendiary bombs were dropped on civilian and military targets. By the time of the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, light and medium bombers were being directed to bomb targets of convenience, because most urban areas had already been destroyed. In the 9-month long civilian bombing campaign, over 400,000  Japanese civilians died.

Japanese civilians died.

Carpet bombing of cities, towns, villages, or other areas containing a concentration of civilians is considered a war crime as of Article 51 of the 1977 Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions. Sometimes, that might make the nations think twice, but some nations, like the German Third Reich, think they can get away with anything. Hitler was crazy, and after deciding on the “Final Solution,” what is a little bit of Carpet Bombing in the mix. Carpet bombing was a horrible use of force, and in World War II and other wars since, it has taken many lives, and in the wrong hands it’s even worse.

When you think of an army tank, the last thing on your mind is a way to make tea, but that became foremost in the minds of the designers of the British tanks. The Brits are well known for drinking their tea, and during World War II, that became a big problem. Apparently the enemy knew about this time-honored tradition, and took advantage of the soldiers who participated in it. During the war years, tea can be documented as being to blame for the loss of approximately 30 British tanks. The men had to exit the tank to brew their tea, and the tanks were then wide open for attack. Something had to be done.

When you think of an army tank, the last thing on your mind is a way to make tea, but that became foremost in the minds of the designers of the British tanks. The Brits are well known for drinking their tea, and during World War II, that became a big problem. Apparently the enemy knew about this time-honored tradition, and took advantage of the soldiers who participated in it. During the war years, tea can be documented as being to blame for the loss of approximately 30 British tanks. The men had to exit the tank to brew their tea, and the tanks were then wide open for attack. Something had to be done.

During World War II there was not time to get this all worked out, but in 1945, all British tanks were equipped with tea-making facilities. The British high command realized that if tank crews could make their tea on the go, then they wouldn’t be susceptible to being “caught with their pants down and their kettles out” by the enemy. So, since the British Centurion MBT (main battle tank) was introduced in late 1945, all British tanks and most AFVs (armored fighting vehicles) have been equipped with tea making facilities. The official name of the unit was Vessel Boiling Electric, but it is usually abbreviated to Boiling Vessel (BV). Unofficially, it was known as a kettle or bivvie. The BV is a square, watertight container which holds one gallon of water. The BV device draws power from the vehicle’s electricity supply and permits the crew not only to make tea, but also boil water or cook food…making their time on the battlefield much safer.

Of course, the BV unit had other important uses too, such as allowing the vehicle’s crew to produce hot water  for washing or drinking purposes and simultaneously heat up canned food. The best part is that all of this can be done inside the vehicle itself, so the crew remains protected from enemy fire. That also protected them if there was danger of radioactive fallout or chemical weapons, which were considered a very real threat during the Cold War. It is now an official requirement for British AFVs to have a BV installed. This requirement is unique to the armed forces of the United Kingdom, and if you ask a British tank crew member what the most important part of the tank, they will tell you that it is the Vessel Boiling Electric, or the BV. Not only does it allow them to make their tea, but it keeps them safe when they are having a meal or drinking that tea.

for washing or drinking purposes and simultaneously heat up canned food. The best part is that all of this can be done inside the vehicle itself, so the crew remains protected from enemy fire. That also protected them if there was danger of radioactive fallout or chemical weapons, which were considered a very real threat during the Cold War. It is now an official requirement for British AFVs to have a BV installed. This requirement is unique to the armed forces of the United Kingdom, and if you ask a British tank crew member what the most important part of the tank, they will tell you that it is the Vessel Boiling Electric, or the BV. Not only does it allow them to make their tea, but it keeps them safe when they are having a meal or drinking that tea.

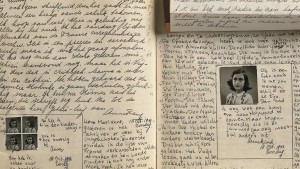

On June 12, 1942, Anne Frank, was a young Jewish girl living in Amsterdam. It was her thirteenth birthday, and as a gift, she was given a diary. Diaries have long been a big deal for girls. I know very few of those in my generation who didn’t have one. Most of those who received them, did little with them. I know that my diary (which I still have, by the way) contains mostly the gibberish of a young girl…mostly bored with the idea of journaling the meager events of my life…or at least that is how I saw them at the time. Looking back, I wish I had maybe taken the whole journaling/diary thing more seriously, because my life, while not as intense as that of Anne Frank, did have meaning, and those events that might have been considered important to my children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren have been, for the most part, lost to the forgetfulness of childhood.

On June 12, 1942, Anne Frank, was a young Jewish girl living in Amsterdam. It was her thirteenth birthday, and as a gift, she was given a diary. Diaries have long been a big deal for girls. I know very few of those in my generation who didn’t have one. Most of those who received them, did little with them. I know that my diary (which I still have, by the way) contains mostly the gibberish of a young girl…mostly bored with the idea of journaling the meager events of my life…or at least that is how I saw them at the time. Looking back, I wish I had maybe taken the whole journaling/diary thing more seriously, because my life, while not as intense as that of Anne Frank, did have meaning, and those events that might have been considered important to my children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren have been, for the most part, lost to the forgetfulness of childhood.

Many of us have heard of, read about, or seen the movie about the events of Anne Frank’s short life. One short month after receiving her diary, Anne and her family went into hiding from the Nazis in rooms behind her father’s office. Anne’s sister, Margot, received a call-up notice around 3pm on July 5, 1942. The Frank family had planned to go into hiding on July 16, 1942, but they decided to leave immediately so that Margot would not have to be deported to a “work camp.” The family left a false trail indicating that they had gone into hiding in Switzerland. According to Anne’s diary, Margot kept a diary of her own, but no trace of Margot’s diary has ever been found. This and her time in the hands of the Nazis was the main period of her diary, because as we know, Anne did not survive the Holocaust into which she and her family had been dragged. The hiding place was not discovered immediately, of course, and for the next two years, the Franks and four other families were hidden, fed, and cared for by Gentile friends. They lived in an annex, whose entrance was hidden behind a moveable bookcase. Following a tip in 1944, the families were discovered by the Gestapo. The Franks were taken to Auschwitz, where Anne’s mother died. Friends in Amsterdam searched the rooms and found Anne’s diary hidden away. They had hoped to save any personal items, so they could be returned to the family, should any of them survive.

Anne and her sister were sent to another camp, Bergen-Belsen, where Anne died a month before the war ended. Anne’s father survived Auschwitz, and after much soul searching, he published Anne’s diary in 1947 as “The Diary of a Young Girl.” The book has been translated into more than 60 languages. Had it not been for World War II, the Holocaust, and Anne’s tragic death from Typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in February 1945, the diary would have most likely have been published, or even written in the way that it was.

The reality is that most diaries aren’t immensely interesting. Most are written by young girls with drama queen emotions, who are bored with their lives, because they are certain that nothing cool happens. Anne’s diary was interesting, because she wasn’t sure how long her life would be, and she wanted to know everything…before it was too late.

The reality is that most diaries aren’t immensely interesting. Most are written by young girls with drama queen emotions, who are bored with their lives, because they are certain that nothing cool happens. Anne’s diary was interesting, because she wasn’t sure how long her life would be, and she wanted to know everything…before it was too late.

Not everyone was surprised at the coming murders of the Jews during the Holocaust. People hoped that the rumors were wrong, and that maybe they war would end before things got that bad, but most knew that if something wasn’t done, things were going to get ugly at some point. In the end, the non-Jews were forced to make a decision…take a stand, or stand by and watch millions of people die.

Not everyone was surprised at the coming murders of the Jews during the Holocaust. People hoped that the rumors were wrong, and that maybe they war would end before things got that bad, but most knew that if something wasn’t done, things were going to get ugly at some point. In the end, the non-Jews were forced to make a decision…take a stand, or stand by and watch millions of people die.

A Danish ambulance driver in Copenhagen, Denmark huddled over a local phone book, circling Jewish names. He had heard that all of Denmark’s Jews were going to be deported, and he knew this was his “moment of truth.” He knew he had to warn every one of these people, before it was too late. He wasn’t alone. Hundreds of everyday Danes sprang into action in late September 1943. They all had one collective goal in mind…to help their Jewish friends and neighbors escape the horrors they knew were coming.

The plan was amazing. Hundreds of people helped Jewish people sneak out of Copenhagen and other towns. They quickly headed toward Danish shores and into the crowded holds of tiny fishing boats. Denmark was about to pull off a spectacular feat…the rescue of the vast majority of its Jewish population. Within a few hours of learning that the Nazis intended to wipe out Denmark’s Jews, nearly all of the Danish Jews had gone into hiding. Within a few days, most of them had escaped Denmark to neutral Sweden. In the end, over 90% of the Danish Jews were snatched out of the hands of Adolf Hitler and his goons, and it was all thanks to ordinary Danes, most of whom refused to accept credit for their ations. I call it a miracle, and the participants…angels!!

The German forces invaded Denmark in April 1940. The Danish government, rather than suffer an inevitable defeat by fighting back, didn’t resist the Nazi hoard. Instead, the Danish government negotiated with the Germans to insulate Denmark from the occupation. In the negotiations, the Nazis promised to be lenient with the country, respecting its rule and neutrality…like they would ever keep that promise. By 1943, tensions had reached a breaking point. Workers began to sabotage the war effort and the Danish resistance ramped up their efforts to fight the Nazis. In response, the Nazis told the Danish government to institute a harsh curfew, forbid public assemblies, and punish saboteurs with death. The Danish government refused, so the Nazis dissolved the government and established martial law.

The Nazis had always been a forbidding presence in Denmark, but now they began really making their presence known. Like everywhere else, the Danish Jews were to be their first targets. The Holocaust was spreading across occupied Europe, and without the protection of the Danish government, which had done its best to shield Jews from the Nazis after realizing that the Nazi promises were worthless, Denmark’s Jewish population was in danger. In late September 1943, the Nazis got word from Berlin that it was time to rid Denmark of its Jews. As was typical for the Nazis, they planned the raid to coincide with a significant Jewish holiday…in this case, Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. Marcus Melchior, a rabbi, got word of the coming raid, and in Copenhagen’s main synagogue, he interrupted services. Melchior said, “We have no time now to continue prayers. We have news that this coming Friday night, the night between the first and second of October, the Gestapo will come and arrest all Danish Jews.” Melchior told the congregation that the Nazis had the names and addresses of every Jew in Denmark, and urged them to flee or hide.

Denmark’s panicked Jewish population sprang into action, but against all odds, so did its Gentiles. Hundreds of people spontaneously began to tell Jews about the upcoming action and help them go into hiding. It was, in the words of historian Leni Yahil, “a living wall raised by the Danish people in the course of one night.” It was amazing, and it can only be classified as a miracle. The Gentile people of Denmark were taking their lives into their own hands too, but they did not care, nor did they consider the cost. All they saw was the horrific injustice of the Nazi plan, and they could not abide by it.

No pre-existing plan had been put in place by the Danish people, but the Jewish people needed their help and nearby Sweden offered an obvious haven to those who were about to be deported. Sweden was still neutral and unoccupied by the Nazis, and they were a fierce ally. It was also close. Some areas of Denmark were just over three miles away from the Swedish coast. Once across, the Jews could apply for asylum there. The Danish culture has long been seafaring, in fact since Viking times. That said, there were plenty of fishing boats and other vessels to spirit Jews toward Sweden. But Danish fishermen were worried about losing their livelihoods and being punished by the Nazis if they were caught. So, rather than put their countrymen in peril, the resistance groups that swiftly formed to help the Jews managed to negotiate standard fees for Jewish passengers, then recruit volunteers to raise the money for passage. That way the fishermen got paid for their risk. The average price of passage to Sweden cost up to a third of a worker’s annual salary.

As often happens, there were fishermen who took advantage of the situation, but more who refused pay, acting without regard to personal gain. Boats were used for some 7,000 Danish Jews who fled to safety in neighboring Sweden. Passage was a terrifying ordeal. Jews gathered in fishing towns, hid on small boats, usually 10 to 15 at a time, giving their children sleeping pills and sedatives to keep them from crying, and struggled to maintain control during the hour-long crossing. Some boats, like the Gerda III, were boarded by Gestapo patrols. Gas came from strange sources. Careful rationing by groups like the “Elsinore Sewing Club,” a resistance unit, helped a few hundred Jews make the crossing.

There were failures sadly. In Gilleleje, a small fishing town, hundreds of refugees were being cared for by locals, when the Gestapo arrived. A collaborator had betrayed a group of Jews hiding in the town church’s attic. Eighty Jews were arrested. Others never got word of the upcoming deportations or were too old or incapacitated to seek help. In the end, about 500 Danish Jews were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto. Of the 500 who were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto, only 51 did not survive the Holocaust. Still, it was the most successful action of its kind during the Holocaust. Some 7,200 Danish Jews were ferried to Sweden.

The rescue was not without German help either. God can reach people even in such a corrupt government. Werner Best, the German who had been placed in charge of Denmark, apparently tipped off some Jews to the

upcoming action and subtly undermined the Nazis’ attempts to stop the Danes from helping Danish Jews. Another helpful factor was that Denmark was one of the only places in Europe that had successfully integrated its Jewish population. Although there was anti-Semitism in Denmark before and after the Holocaust, the Nazis’ war on Jews was largely viewed as a war against Denmark itself.

upcoming action and subtly undermined the Nazis’ attempts to stop the Danes from helping Danish Jews. Another helpful factor was that Denmark was one of the only places in Europe that had successfully integrated its Jewish population. Although there was anti-Semitism in Denmark before and after the Holocaust, the Nazis’ war on Jews was largely viewed as a war against Denmark itself.