World War II

The 83rd anniversary of Pearl Harbor, at least for the Baby Boomer generation and older, prompts reflection on the United States’ stance of often waiting for an initial attack before responding. While this is not always the case, it appears to be a common scenario. The US strives to act as a peacemaker, and the decision to go to war is never taken lightly due to the grave consequences of taking lives. Typically, numerous warnings are issued before any action is taken, and frequently, it’s too late to preemptively strike. The first to strike is often labeled the aggressor, but there are times when ample warning signals an imminent attack, yet the response is still delayed, until the attack occurs, resulting in loss of life and leaving the survivors to deal with the aftermath rather than considering an immediate counterstrike. Of course, the reverse is hard to deal with too, because we would come off as being the aggressor, and that just isn’t our style.

The 83rd anniversary of Pearl Harbor, at least for the Baby Boomer generation and older, prompts reflection on the United States’ stance of often waiting for an initial attack before responding. While this is not always the case, it appears to be a common scenario. The US strives to act as a peacemaker, and the decision to go to war is never taken lightly due to the grave consequences of taking lives. Typically, numerous warnings are issued before any action is taken, and frequently, it’s too late to preemptively strike. The first to strike is often labeled the aggressor, but there are times when ample warning signals an imminent attack, yet the response is still delayed, until the attack occurs, resulting in loss of life and leaving the survivors to deal with the aftermath rather than considering an immediate counterstrike. Of course, the reverse is hard to deal with too, because we would come off as being the aggressor, and that just isn’t our style.

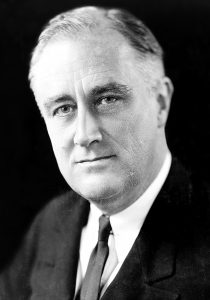

On December 7, 1941, the United States found itself in a precarious position. Despite repeatedly warning Japan, the United States using the Hull Note as a show of the ultimate caution, tried to avoid entering World War II. The Hull Note officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) and the Japanese declaration of war (seven and a half hours after the attack began). Unfortunately, Japan to all that as a show of weakness. Nevertheless, knowing that Japan would likely not comply, and essentially declaring war, the US still hoped they would proceed slowly, perhaps  even reconsider their course. Conversely, Japan acted swiftly, dispatching their strike force towards Pearl Harbor and simultaneously sending a decoy towards Thailand to mislead the US. Then, believing an attack on Thailand was imminent, President Roosevelt implored Emperor Hirohito via telegram to act “for the sake of humanity” and prevent further devastation. The US endeavored to maintain peace.

even reconsider their course. Conversely, Japan acted swiftly, dispatching their strike force towards Pearl Harbor and simultaneously sending a decoy towards Thailand to mislead the US. Then, believing an attack on Thailand was imminent, President Roosevelt implored Emperor Hirohito via telegram to act “for the sake of humanity” and prevent further devastation. The US endeavored to maintain peace.

After transmitting the telegram, President Roosevelt was working on his stamp collection alongside his personal advisor, Harry Hopkins. They deliberated over Japan’s rejection of the Hull Note. Hopkins proposed a preemptive strike by America, but President Roosevelt maintained that it was not an option. Unbeknownst to them, it was already too late for a first strike…time had run out. The Japanese forces were en route to Pearl Harbor, where a significant segment of the Pacific Fleet lay anchored, vulnerable to attack. The impending ambush would devastate 18 US ships, including the Arizona, Virginia, California, Nevada, and West Virginia, either destroyed, sunk, or capsized. Over 180 aircraft were destroyed on the ground, with an additional 150 damaged, leaving a mere 43 operational. American casualties exceeded 3,400, with over 2,400 fatalities—1,000 of which occurred on the Arizona alone. The Japanese incurred fewer than 100 losses.

It often appears that the party who strikes first, swiftly and with the element of surprise, ultimately fares better. The side caught off guard, or the one that ignored the warning signs, is usually defeated. With one of the strongest military forces on Earth, America should not be taken by surprise. I believe that overconfidence in one’s strength, leading to a lack of vigilance, can result in the downfall of even the mightiest. The United States has been such a force, but our reluctance to preemptively strike seems to invite repeated attacks without warning. It is only after such attacks that we seem to retaliate.

It’s indeed a dilemma, perhaps reflective of President Roosevelt’s perspective. If we strike first, we’re vilified globally as the aggressors, akin to those at Pearl Harbor. If we don’t, we face condemnation from our own citizens. Moreover, our intelligence isn’t infallible, leading to situations like the surprise attack on December 7th, 1941, when we expected honor from an adversary who did not feel bound by it. It seems that although being

attacked unprovoked is undesirable, we must still act honorably and not launch a preemptive strike merely based on anticipated aggression. Otherwise, we become indistinguishable from those nations we confront in war for their acts of invasion. Nevertheless, it remains a huge challenge to always be the nation that does the right things, especially when there is a profound mistrust of our enemies…because we know better.

attacked unprovoked is undesirable, we must still act honorably and not launch a preemptive strike merely based on anticipated aggression. Otherwise, we become indistinguishable from those nations we confront in war for their acts of invasion. Nevertheless, it remains a huge challenge to always be the nation that does the right things, especially when there is a profound mistrust of our enemies…because we know better.

On the shores of Lake Ontario between Whitby and Oshawa is an area now known as Intrepid Park, but that wasn’t always its name, and in was now just an innocent park then either. Today, in fact, few remnants suggest the fascinating history of the site. During the World War II, it served as Camp X, the clandestine intelligence and espionage training center for the Allies. Officially designated as Secret Training Center 103, with the informal designation, Camp X, the site fully captures the top-secret essence of its operations. The site is currently recognized as Intrepid Park, named in honor of Sir William Stephenson’s codename Intrepid. Stephenson was the Director of British Security Coordination (BSC) who was responsible for founding the training center.

On the shores of Lake Ontario between Whitby and Oshawa is an area now known as Intrepid Park, but that wasn’t always its name, and in was now just an innocent park then either. Today, in fact, few remnants suggest the fascinating history of the site. During the World War II, it served as Camp X, the clandestine intelligence and espionage training center for the Allies. Officially designated as Secret Training Center 103, with the informal designation, Camp X, the site fully captures the top-secret essence of its operations. The site is currently recognized as Intrepid Park, named in honor of Sir William Stephenson’s codename Intrepid. Stephenson was the Director of British Security Coordination (BSC) who was responsible for founding the training center.

The facility was a collaborative effort involving the Canadian military, with support from Foreign Affairs and the RCMP, and was commanded by the BSC. It also had strong links with MI6. While the United States was officially neutral at that time, the camp aimed to strengthen ties between the US and Great Britain. The camp boasted a communications tower called Hydra, which was equipped to send and transmit radio and telegraph messages. The camp officially opened on December 6, 1941, and with the Pearl Harbor attack the next day, the US abandoned its stance of neutrality and actively participated in the war, including the training of troops at Camp X.

The camp provided training in diverse skills such as sabotage, subversion, intelligence gathering, lock picking, explosives handling, radio operation, code encryption/decryption, partisan recruitment, silent killing, and hand-to-hand combat. Trainees also learned communication methods, including Morse code. The camp was shrouded in such secrecy that even the Canadian Prime Minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, did not completely understand its purpose. Reports indicate that graduates worked as “secret agents, security personnel, intelligence officers, or psychological warfare experts, serving in clandestine operations. Many were captured,

tortured, and executed; survivors received no individual recognition for their efforts.” The facility was in operation throughout World War II. The training facility ceased operations before the end of 1944. By 1969, the buildings were dismantled, and a monument placed there.

tortured, and executed; survivors received no individual recognition for their efforts.” The facility was in operation throughout World War II. The training facility ceased operations before the end of 1944. By 1969, the buildings were dismantled, and a monument placed there.

Apparently, Ian Flemming visited or was trained at Camp X, because it is said that he used the site as a model for his training facility on the “007” series of movies. Fleming worked in intelligence most of his naval career. In fact, much of the background to the stories came from Fleming’s previous work in the Naval Intelligence Division or from events he knew of from the Cold War. His work there is very likely what made those movies so believable.

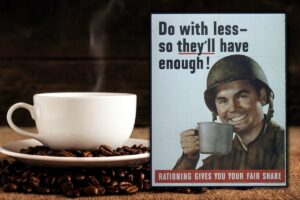

War usually brings with it, shortages and rationing. On November 29, 1942, coffee was added to the list of rationed items in the United States. Now, people can live without some things, but I would think that coffee would be a really hard item to add to that list. The coffee production in Latin America was at a record, but it made no difference, the increasing demand from military and civilian sectors, along with the pressing needs of shipping for other wartime efforts, necessitated the restriction of its availability.

War usually brings with it, shortages and rationing. On November 29, 1942, coffee was added to the list of rationed items in the United States. Now, people can live without some things, but I would think that coffee would be a really hard item to add to that list. The coffee production in Latin America was at a record, but it made no difference, the increasing demand from military and civilian sectors, along with the pressing needs of shipping for other wartime efforts, necessitated the restriction of its availability.

The truth is that scarcity or shortages were seldom the cause of rationing during the war. Rationing was typically implemented for two main reasons…to ensure an equitable distribution of resources and food to all citizens and to prioritize military needs for certain raw materials in light of the current emergency.

At first, the restriction on the use of certain items was voluntary. People were simply asked to cut back. The problem is that voluntary cutting back seldom works. Also, President Roosevelt initiated “scrap drives” to collect discarded rubber items like old garden hoses, tires, and bathing caps, especially after Japan seized the Dutch East Indies, a key rubber supplier for the United States. These collected items could be exchanged at gas stations for a penny per pound. In the early stages of the war, patriotism and the eagerness to support the war effort was enough.

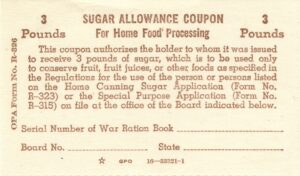

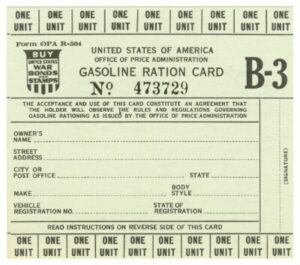

As US shipping, including oil tankers, became increasingly susceptible to German U-boat attacks, gasoline was the first commodity to be rationed. In seventeen eastern states, car owners were limited to three gallons of gasoline weekly beginning in May 1942. By year’s end, rationing had expanded nationwide, with drivers required to affix ration stamps to their car windshields. Things like butter, were reserved for military use, and so were also rationed. Also limited were coffee, sugar, and milk. In fact, approximately one-third of all food typically consumed by civilians was rationed during the war at some point. We had to make sure our troops had what they needed. They were fighting for our freedom, and we would sacrifice so they could have

what they needed. The American people were determined and willing. Of course, that didn’t stop the black market from becoming a source for rationed items, selling goods at prices above those set by the Office of Price Administration to Americans who could afford the marked-up costs. Nevertheless, certain items were removed from the rationing list ahead of time; coffee became available in July 1943, but sugar remained rationed until June 1947.

what they needed. The American people were determined and willing. Of course, that didn’t stop the black market from becoming a source for rationed items, selling goods at prices above those set by the Office of Price Administration to Americans who could afford the marked-up costs. Nevertheless, certain items were removed from the rationing list ahead of time; coffee became available in July 1943, but sugar remained rationed until June 1947.

The HMT Rohna, originally known as SS Rohna, was a passenger and cargo liner belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company. Constructed in Tyneside in 1926, it was one of two new vessels ordered by the British India Line in 1925 for its Madras–Nagapatam–Singapore route. These sister ships had slight variations…being built at different shipyards with different engines. Hawthorn Leslie and Company constructed the Rohna in Hebburn on Tyneside, while Barclay, Curle and Company built the Rajula in Glasgow on Clydeside. The two ships were completed and launched around the same time in mid-1926.

The HMT Rohna, originally known as SS Rohna, was a passenger and cargo liner belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company. Constructed in Tyneside in 1926, it was one of two new vessels ordered by the British India Line in 1925 for its Madras–Nagapatam–Singapore route. These sister ships had slight variations…being built at different shipyards with different engines. Hawthorn Leslie and Company constructed the Rohna in Hebburn on Tyneside, while Barclay, Curle and Company built the Rajula in Glasgow on Clydeside. The two ships were completed and launched around the same time in mid-1926.

The Rohna was launched on August 24, 1926, and her construction was completed by November 5. Named after a village in Sonipat, Punjab, India, she featured 15 corrugated furnaces heating five single-ended boilers, which together had a heating surface of 14,080 square feet. These boilers supplied steam at 215 lbf/in^2 (pounds per square inch) to two four-cylinder quadruple expansion steam engines, yielding a combined power of 984 Nominal Horsepower (NHP). Each engine propelled one of the ship’s twin screws, enabling the Rohna to achieve 984 NHP or 5,000 Indicated Horsepower (IHP). On her sea trials, she reached 14.3 knots (2, with a cruising speed of 12.5 knots). By 1934, the Rohna was equipped with wireless direction-finding equipment.

As the United Kingdom entered the World War II in September 1939, the Rohna was navigating the Indian Ocean. Other than a journey from Karachi to Suez with Convoy K 4, the Rohna sailed unescorted between Rangoon and Madras until the end of November. Departing Bombay on December 10th, she headed for the Mediterranean, transited the Suez Canal on December 20-21, and arrived in Marseille on December 26th. From January 3, 1940, to March 10th, she moved unescorted between Marseille and the Port of Haifa in Mandatory Palestine, initially as part of convoys but later, after January 29th, on her own.

On March 15, 1940, the Rohna sailed back through the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean, where she operated unescorted between Bombay, Rangoon, and Colombo until June. In May, she was requisitioned as a troop ship, and on June 6th, she departed from Bombay to Durban. She continued to operate between Durban, Mombasa, and Dar es Salaam until July 28th, when she embarked from Mombasa to return to Bombay.

The Rohna transported troops from Bombay to Suez in August 1940 with Convoy BN 3, and from Bombay to Port Sudan in September/October 1940 with Convoy BN 6. Subsequent journeys included Bombay to Suez in November 1940 with Convoy BN 8A, Colombo to Suez in February 1941 with Convoy US 8/1, and Bombay to Singapore in March 1941 with Convoy BM 4. Following the Iraqi coup d’état in April 1941, the Rohna was directed to Karachi, from where she transported early units of Iraqforce to Basra in Convoy BP 2. During the Anglo-Iraqi War in May, she completed a second voyage from Karachi to Basra with Convoy BP 5. After the Allied triumph in Iraq at May’s end, she continued shuttling between Basra and Bombay, departing to Basra with BP-series convoys and returning independently.

On December 8, 1941, Japan invaded Malaya. The following month, Rohna departed Bombay for Singapore with Convoy BM 10, arriving on January 25, 1942. She set sail on January 28 in Convoy NB 1, two weeks before Singapore fell to Japan. From March 1942, Rohna spent a year navigating the Indian Ocean, visiting Bombay, Karachi, Colombo, Basra, Aden, Suez, Khorramshahr, Bandar Abbas, Bahrain, and Abadan, sometimes as part of convoys, often unescorted. In March 1943, she embarked from Bombay with Convoy BA 40 to Aden, then proceeded independently to Suez, passing through the canal on April 6–7.

Throughout the rest of her service, Rohna was instrumental in supporting the North African Campaign, as well as the Allied invasions of Sicily and Italy. Until early July, she operated independently, navigating between Alexandria, Tripoli, and Sfax. She primarily joined convoys, plying the routes between Alexandria,

Malta, Tripoli, Augusta, Port Said, Bizerte, and Oran.

Malta, Tripoli, Augusta, Port Said, Bizerte, and Oran.

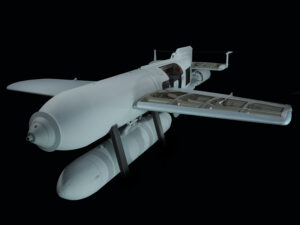

Her requisition as a troop carrier in 1940, at the onset of World War II, placed a target of sorts on her back, and in November 1943, the Rohna was sunk in the Mediterranean by a Henschel HS 293 guided glide bomb launched from a Luftwaffe aircraft. The attack resulted in the deaths of over 1,100 individuals, the majority being United States troops.

On November 19, 1941, a naval engagement took place off the coast of Western Australia between the Australian light cruiser, the HMAS Sydney, commanded by Captain Joseph Burnett, and the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran, led by Fregattenkapitän Theodor Detmers. The encounter occurred around 106 nautical miles from Dirk Hartog Island. The battle, which was a one-on-one confrontation, lasted for thirty minutes, resulting in the destruction of both vessels.

On November 19, 1941, a naval engagement took place off the coast of Western Australia between the Australian light cruiser, the HMAS Sydney, commanded by Captain Joseph Burnett, and the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran, led by Fregattenkapitän Theodor Detmers. The encounter occurred around 106 nautical miles from Dirk Hartog Island. The battle, which was a one-on-one confrontation, lasted for thirty minutes, resulting in the destruction of both vessels.

Beginning November 24th, following the failure of the Sydney to return to port, extensive air and sea searches were initiated. Survivors from the Kormoran were rescued at sea aboard boats and rafts, while others reached land at Quobba Station, situated 37 miles north of Carnarvon. In total, 318 out of the 399 Kormoran crew members survived. Debris from the Sydney was discovered, but none of the 645 crew members survived. This event marked the most devastating loss of life in the Royal Australian Navy’s history, the largest loss of an Allied warship with all hands during World War II and dealt a severe blow to Australian wartime morale. The fate of the Sydney was revealed to Australian authorities through the Kormoran survivors, who were detained in prisoner of war camps until the end of the war.

The HMAS Sydney, a Modified Leander class light cruiser, was one of three in the Royal Australian Navy (RAN). It was originally constructed for the Royal Navy, but it was acquired by the Australian government as a  replacement for the HMAS Brisbane and commissioned into the RAN in September 1935. Measuring 562 feet 4 inches in length, the Sydney had a displacement of 9,080 tons (8,940 long tons). Its primary armament consisted of eight 6-inch guns across four twin turrets, designated “A” and “B” at the front and “X” and “Y” at the rear. Additionally, it was equipped with four 4-inch anti-aircraft guns, nine .303-inch machine guns, and eight 21-inch torpedo tubes arranged in two quadruple mountings. The cruiser also housed a Supermarine Walrus amphibious aircraft.

replacement for the HMAS Brisbane and commissioned into the RAN in September 1935. Measuring 562 feet 4 inches in length, the Sydney had a displacement of 9,080 tons (8,940 long tons). Its primary armament consisted of eight 6-inch guns across four twin turrets, designated “A” and “B” at the front and “X” and “Y” at the rear. Additionally, it was equipped with four 4-inch anti-aircraft guns, nine .303-inch machine guns, and eight 21-inch torpedo tubes arranged in two quadruple mountings. The cruiser also housed a Supermarine Walrus amphibious aircraft.

The Kormoran was commissioned in October 1940 and underwent modifications to reach a length of 515 feet and a gross register tonnage of 8,736. This raider was equipped with six single 5.9-inch guns…two positioned on the forecastle and quarterdeck, and the remaining two along the centerline…as its primary armament. This was complemented by two 1.46-inch anti-tank guns, five 0.79-inch anti-aircraft autocannons, and six 21-inch torpedo tubes, which included a twin above-water mount on each side and two single underwater tubes. The 5.9-inch guns were hidden behind false hull plates and cargo hatch walls that could swing open upon the command to decamouflage. The secondary armaments were mounted on hydraulic lifts concealed within the superstructure, allowing the ship to masquerade as various Allied or neutral vessels.

The battle has been the subject of much controversy, particularly in the years preceding the discovery of the two wrecks in 2008. The defeat of the purpose-built warship Sydney by the modified merchant vessel Kormoran was a topic of much speculation, inspiring numerous books and prompting two official government inquiry reports, released in 1999 and 2009.

German accounts, deemed truthful and generally accurate by Australian interrogators during the war and by most subsequent analyses, indicate that Sydney came so close to Kormoran that it forfeited the benefits of its heavier armor and superior gun range. Despite this, numerous post-war publications have speculated about an

extensive cover-up regarding Sydney’s loss, alleged violations of the laws of war by the Germans, the massacre of Australian survivors after the battle, or secret involvement by the Empire of Japan in the action (prior to its official war declaration in December). Presently, there is no evidence to substantiate these theories, leaving the battle and the loss of the two ships a mystery to this day.

extensive cover-up regarding Sydney’s loss, alleged violations of the laws of war by the Germans, the massacre of Australian survivors after the battle, or secret involvement by the Empire of Japan in the action (prior to its official war declaration in December). Presently, there is no evidence to substantiate these theories, leaving the battle and the loss of the two ships a mystery to this day.

Aunt Ruth Wolfe grew up on a farm surrounded by horses…her absolute favorite animal. The country girl lifestyle suited her. During World War II, while her brother, my father Allen Spencer, served in the Army Air Forces, she worked the farm with her mother brother, Bill. She took on the farm work and also worked as a welder in the shipyards, becoming one of the Worl War II’s well known “Rosie the Riveters.” Later, married to my Uncle Jim Wolfe, they lived in the country near Casper, Wyoming…gardening, canning, and raising farm animals. Aunt Ruth was a capable woman, achieving anything she set her

Aunt Ruth Wolfe grew up on a farm surrounded by horses…her absolute favorite animal. The country girl lifestyle suited her. During World War II, while her brother, my father Allen Spencer, served in the Army Air Forces, she worked the farm with her mother brother, Bill. She took on the farm work and also worked as a welder in the shipyards, becoming one of the Worl War II’s well known “Rosie the Riveters.” Later, married to my Uncle Jim Wolfe, they lived in the country near Casper, Wyoming…gardening, canning, and raising farm animals. Aunt Ruth was a capable woman, achieving anything she set her  mind to. Her talents were many, ranging from the hard work of farming and canning to playing musical instruments and painting.

mind to. Her talents were many, ranging from the hard work of farming and canning to playing musical instruments and painting.

One of the most unexpected decisions Aunt Ruth and Uncle Jim made was moving to Vallejo, California. It’s surprising that someone who loved country living would choose a city. Vallejo, a suburb of San Francisco, is a sharp contrast to Casper, Wyoming, and Holyoke, Minnesota, where Aunt Ruth grew up. Perhaps they just wanted a change, which I get since my family transitioned from rural to urban living in Casper. Still, I can see the draw of city life and California’s milder climate probably better suited my aunt and uncle.

After living in California for a while, the country life drew them back to the mountains of Washington state. The move to the mountains didn’t surprise me much; country living seemed to be in my aunt and uncle’s blood, as much a part of their being, as their DNA. Once they settled in eastern Washington, they stayed put. They purchased a mountaintop

and built three cabins: one for themselves, one for their daughter Shirley and her husband Shorty Cameron, and one for their son Terry and his family. For Aunt Ruth and Uncle Jim, this was their final abode. Having visited their mountaintop, I understand its allure, but since moving back to town, I’ve realized I wouldn’t want to live in the countryside or on a mountaintop permanently. Nonetheless, it was their safe haven. Today would have marked Aunt Ruth’s 99th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Aunt Ruth. We love and miss you very much.

and built three cabins: one for themselves, one for their daughter Shirley and her husband Shorty Cameron, and one for their son Terry and his family. For Aunt Ruth and Uncle Jim, this was their final abode. Having visited their mountaintop, I understand its allure, but since moving back to town, I’ve realized I wouldn’t want to live in the countryside or on a mountaintop permanently. Nonetheless, it was their safe haven. Today would have marked Aunt Ruth’s 99th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Aunt Ruth. We love and miss you very much.

As with any attack, planning must be done before any action can take place. The attack on Pearl Harbor was no exception. A little more than a month, on November 5, 1941, the Combined Japanese Fleet received Top-Secret Order Number 1, stating that in just over a month, Pearl Harbor, along with Malaya (now Malaysia), the Dutch East Indies, and the Philippines, was to be bombed. There was much preparation to do, and very little time to do it. Failure would not be an option, because failure would mean death, and in fact, the battle was a planned death for the kamikaze pilots.

As with any attack, planning must be done before any action can take place. The attack on Pearl Harbor was no exception. A little more than a month, on November 5, 1941, the Combined Japanese Fleet received Top-Secret Order Number 1, stating that in just over a month, Pearl Harbor, along with Malaya (now Malaysia), the Dutch East Indies, and the Philippines, was to be bombed. There was much preparation to do, and very little time to do it. Failure would not be an option, because failure would mean death, and in fact, the battle was a planned death for the kamikaze pilots.

The problem was that the relationship between the United States and Japan had rapidly worsened following Japan’s occupation of Indochina in 1940 and the subsequent threat to the Philippines, which is an American territory. With the seizure of the Cam Ranh naval base, located roughly 800 miles from Manila, something had to be dome. In response, the United States seized all Japanese assets within its borders and shut the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping. In September 1941, President Roosevelt, with a statement prepared by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, warned that the United States would go to war with Japan if it continued to invade territories in Southeast Asia or the South Pacific. The United States hoped, and yes even expected the Japanese to comply.

Nevertheless, despite ongoing negotiations between the United States Secretary of State and his Japanese counterpart to alleviate tensions, Hideki Tojo, the War Minister soon to become Prime Minister, was not inclined to retreat from occupied territories. Viewing the American “threat” of war as an ultimatum, he readied to initiate the first strike in a confrontation with the United States…the attack on Pearl Harbor.

We all know what happened next, but could it have been prevented? I don’t believe that Japan had any interest in preventing a war with the United States. So, it would have been up to the United States to pave the way for peace between the two countries…if that was even possible. Since I don’t believe it was possible, due to Japan’s plans, The other aspect of the question is how America might have prevented Pearl Harbor. It is likely that intelligence shortcomings and underestimation of the Japanese played a role. However, it is argued that the American military hawks and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt may have seen the attack as a necessary catalyst to persuade the nation to enter the war against the tyrannies of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. I don’t know for sure, and I hate to say that was exactly it, but I wonder if they expected the attack to be as bad as it ended up being.

Numerous theories speculate on whether Roosevelt, or even Great Britain’s Winston Churchill, had foreknowledge of the impending attack. However, it seems improbable. Military leaders typically do not permit such attacks due to the unpredictability of the consequences. Consider the possibilities: the attack occurring prematurely and sinking the carriers, the destruction of oil facilities, or the Japanese invasion and occupation of Hawaii. These are risks that no military leader would willingly take, regardless of their desire for a pretext to enter the war. It is probable that Roosevelt anticipated an attack, although the specifics of when and where remained uncertain.

To address the question of how America could have avoided Pearl Harbor, one must dig deeper into history, far beyond the oil embargoes of the early 1940s. It could be argued that the path to Pearl Harbor was set as early as July 8, 1853, when American Commodore Matthew Perry entered Tokyo Bay with his four ships, aiming to reestablish regular trade between Japan and the Western world. It all seemed innocent enough, but while Japan was once receptive to Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch influences. Then, with each nation attempting to introduce Western culture and religion, Japan began to have issues with them. Within a few decades, these Western powers were expelled, leaving only the Dutch with limited trading privileges through Dejima, a small man-made island in Nagasaki.

The Japanese quickly assimilated the practices of their adversaries, which included adopting a Western-trained military. The Army was advised by the French and later the Germans, while the Navy was guided by British advisors and equipped with British-built warships. Japan managed to defeat its long-standing rival China, annexing Taiwan and Korea into its gradually expanding empire. In 1904-1905, Japan, was hardly a regional power a mere fifty years prior, overwhelmed Imperial Russia in a fierce conflict. The victory followed a surprise assault on the Russian Navy at Port Arthur…something that American military planners in 1941 should have taken notice of! The initial attack aimed to incapacitate the Russians, yet the pivotal battle occurred at Tsushima Straits, where Admiral Togo Heihaciro led the Japanese fleet to obliterate eight Russian battleships.

In World War I, which followed less than ten years later, Japan joined with the Russians and aided the British in seizing the German-held Tsingtao in China. Japan also took control of the Marianas, the Caroline Islands, and the Marshall Islands. All this further fueled Japan’s ambitions concerning Chinese territories and the American-

controlled Philippines for potential expansion. Then, came “the straw that broke the camel’s back” for the Americans, and with the threat against the Philippines, the attack of Pearl Harbor was set in motion…all due to the actions taken to protect the Philippines.

controlled Philippines for potential expansion. Then, came “the straw that broke the camel’s back” for the Americans, and with the threat against the Philippines, the attack of Pearl Harbor was set in motion…all due to the actions taken to protect the Philippines.

Had Perry not “opened” Japan, this sequence of events might not have unfolded. This is not to imply Japan would not have modernized, but the trajectory could have been altered. Without the Emperor’s restoration, the Boshin War might not have taken place, possibly preventing the swift military reforms that followed. Of course, all this could be speculation, but the experts think it is fact.

On October 24, 1945, the United Nations Charter, adopted and signed on June 26, 1945, came into effect. The United Nations (UN) emerged from a “perceived” need for a mechanism superior to the League of Nations in arbitrating international conflicts and negotiating peace. The escalating Second World War prompted the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union to draft the initial UN Declaration, which 26 nations signed in January 1942 as an official stance against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan. It all seemed like a good idea, and perhaps was drafted with good intentions, but it is my opinion that the UN has failed miserably to accomplish any of the goals it set out to achieve.

On October 24, 1945, the United Nations Charter, adopted and signed on June 26, 1945, came into effect. The United Nations (UN) emerged from a “perceived” need for a mechanism superior to the League of Nations in arbitrating international conflicts and negotiating peace. The escalating Second World War prompted the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union to draft the initial UN Declaration, which 26 nations signed in January 1942 as an official stance against the Axis Powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan. It all seemed like a good idea, and perhaps was drafted with good intentions, but it is my opinion that the UN has failed miserably to accomplish any of the goals it set out to achieve.

The foundational principles of the UN Charter were initially shaped during the San Francisco Conference, which began on April 25, 1945. This conference established the framework for a new international organization intended to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom.” The Charter further outlined two additional vital goals. They were to maintain the principles of equal rights and self-determination for all peoples…initially intended to safeguard smaller nations at risk of being overtaken by the larger Communist powers emerging after the war, and to promote international collaboration to tackle worldwide economic, social, cultural, and humanitarian issues.

Following the war’s end, the responsibility of negotiating and maintaining peace was assigned to the newly established UN Security Council, which included the United States, Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and China. Each member possessed veto power. Winston Churchill implored the United Nations to employ its charter to promote a new, united Europe…a unity characterized by its opposition to communist expansion in both the East and the West. Yet, given the composition of the Security Council, achieving this proved more challenging than anticipated. I suppose that the distain felt by many people, for the United Nations, could have arisen from an impossible task, but more likely it came from flawed people who placed their own agenda ahead of the real needs of the people.

The United Nations is subject to criticism for a variety of reasons, including its policies, ideology, equality of representation, administrative practices, enforcement of decisions, and perceived ideological biases. Critics often cite a lack of success within the organization, noting failures in both preventative measures and in de-escalating conflicts ranging from social disputes to full-blown wars. Additional criticisms involve accusations of antisemitism, appeasement, collusion, promotion of globalism, inaction, and the exertion of undue influence by

powerful nations within the General Assembly, as well as corruption and misallocation of resources. In my opinion, and that of many other people, that the UN should be dissolved, or at the very least, that the United States should withdraw and expel the United Nations from this nation. While some may disagree, this is my viewpoint.

powerful nations within the General Assembly, as well as corruption and misallocation of resources. In my opinion, and that of many other people, that the UN should be dissolved, or at the very least, that the United States should withdraw and expel the United Nations from this nation. While some may disagree, this is my viewpoint.

The 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron, part of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAF), is stationed in Edinburgh, Scotland. Established on October 14, 1925, at RAF Turnhouse, it served as a day bomber unit within the Auxiliary Air Force. Initially, the squadron operated DH.9As (a British single engine biplane) and utilized Avro 504Ks (a biplane bomber) for training purposes. In March 1930, it transitioned to Wapitis (a two-seater general purpose military biplane), which were subsequently replaced by Harts (a British two-seater biplane light bomber) in February 1934. On October 24, 1938, the squadron was reclassified as a fighter unit, operating Hinds (a British light bomber) until the introduction of Gladiators (a British biplane fighter) in late March 1939. Over those years the men of 603 Squadron made many equipment transitions.

The 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron, part of the Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAF), is stationed in Edinburgh, Scotland. Established on October 14, 1925, at RAF Turnhouse, it served as a day bomber unit within the Auxiliary Air Force. Initially, the squadron operated DH.9As (a British single engine biplane) and utilized Avro 504Ks (a biplane bomber) for training purposes. In March 1930, it transitioned to Wapitis (a two-seater general purpose military biplane), which were subsequently replaced by Harts (a British two-seater biplane light bomber) in February 1934. On October 24, 1938, the squadron was reclassified as a fighter unit, operating Hinds (a British light bomber) until the introduction of Gladiators (a British biplane fighter) in late March 1939. Over those years the men of 603 Squadron made many equipment transitions.

In August 1939, the squadron commenced yet another transition, this time to Spitfires (a British single-seat fighter aircraft). As the war loomed closer, the squadron shifted to full-time operations. Within two weeks of the outbreak of World War II, Brian Carbury was permanently assigned, and the squadron started receiving Spitfires, transferring its Gladiators to other squadrons throughout October.

Scotland was within the range of Nazi Germany’s long-range bombers and reconnaissance planes. The Luftwaffe primarily targeted the Royal Naval Home Fleet at Scapa Flow. The 603 Squadron, now equipped with Spitfires, was ready in time to intercept the first German air raid on the British Isles on October 16th. It succeeded in shooting down a Junkers Ju 88 bomber over the Firth of Forth, north of Port Seton…marking the first enemy aircraft downed over Great Britain since 1918 and the RAF’s initial victory in World War II. The squadron continued its defensive role in Scotland until August 27, 1940, after which it rotated to Southern England, joining Number 11 Group at RAF Hornchurch. There, it participated in the remaining months of the Battle of Britain, starting from August 27, 1940.

Two days after becoming operational in southern England, Carbury secured his first of 15½ victories (not sure how one has a half victory), ranking as the fifth highest scoring fighter ace of the battle. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bar with 603 Squadron during the conflict. Air Commodore Ronald ‘Ras’ Berry achieved approximately 9 (of a final total of 14) victories at this time, while RAF Officer ‘Sheep’ Gilroy claimed more than 6 victories. Flight Lieutenant Richard Hillary, with 5 victories, was shot down on September 3rd during a skirmish with BF 109s of Jagdgeschwader 26 off Margate at 10:04am. Rescued by the Margate lifeboat, he suffered severe burns and subsequently spent three years in hospital, where he authored the book, The Last Enemy. Recent academic research, including an examination of German records, has identified 603 Squadron as the highest-scoring squadron in the Battle of Britain by its conclusion.

Upon returning to Scotland in late December, Carbury inflicted damage on a Ju 88 over Saint Abb’s Head on Christmas Day. He then departed from the squadron in January 1941 to serve as an instructor at the Central

Flying School. By May 1941, the squadron had relocated southward to participate in sweeps over France, known as “rhubarbs,” which continued until the year’s end.

Flying School. By May 1941, the squadron had relocated southward to participate in sweeps over France, known as “rhubarbs,” which continued until the year’s end.

Following a period in Scotland, 603 Squadron departed in April 1942 for the Middle East, with its ground echelon arriving in early June. Simultaneously, Flight Sergeant Joe Dalley transitioned from the squadron to Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) duties, piloting a Spitfire PR from RAF Benson directly to Malta. There, he joined 69 Squadron RAF, becoming one of the four pilots dubbed the “Eyes and Ears” of the Island. The squadron’s aircraft were loaded onto the US aircraft carrier Wasp and launched towards Malta on April 20th to bolster the island’s hard-pressed defenders. After almost four months of defending Malta, the surviving pilots and planes were integrated into 229 Squadron on August 3, 1942.

By the end of June 1942, the ground echelon of 603 Squadron had relocated to Cyprus, where it operated as a servicing unit for six months before its return to Egypt. In February 1943, the arrival of Bristol Beaufighters and their crews marked the commencement of convoy patrols and escort missions along the North African coastline. August saw the initiation of sweeps over the Aegean’s German-occupied islands and areas off Greece. The squadron continued its assaults on enemy shipping until a scarcity of targets facilitated its return to the UK in December 1944.

On January 10, 1945, 603 Squadron reformed at RAF Coltishall and, in a curious twist of fate, inherited the Spitfires and some personnel of 229 Squadron RAF…the very squadron that had previously absorbed 603 Squadron at Ta’ Qali in 1942. Fighter-bomber operations commenced in February over the Netherlands and persisted until April. Subsequently, the squadron returned to its home base at Turnhouse for the concluding days of the war. The squadron was officially disbanded on August 15, 1945.

603 Squadron was reestablished as part of the Auxiliary Air Force on May 10, 1946, and started recruiting for a Spitfire squadron in June at RAF Turnhouse. The squadron received its first Spitfire in October and operated this aircraft until it transitioned to the De Havilland Vampire FB.5s in May 1951. By July, the squadron was fully equipped with the new aircraft, which it flew until the unit was disbanded on March 10, 1957.

The new 603 Squadron originated from Number 2 (City of Edinburgh) Maritime Headquarters Unit in October 1999, providing the foundation for the new 602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron RAuxAF in 2006. 603 Squadron continued to be based in Edinburgh. In 2007, to mark the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight, the Flight’s Supermarine Spitfire IIa, P7350, which served in 603 Squadron during the Battle of Britain, bore the squadron’s code XT-L, the same as Gerald ‘Stapme’ Stapleton’s personal aircraft, for two years.

For several years leading up to 2013, the main trade at 603 Squadron was the RAF Regiment, although the Squadron also provided support in Mission Support and Flight Operations trades. In late 2012, it was announced that the Squadron would start recruiting for the RAF Police in 2013. Consequently, the Squadron has transitioned to primarily being an RAF Police unit, while still retaining a Flight of the RAF Regiment.

For several years leading up to 2013, the main trade at 603 Squadron was the RAF Regiment, although the Squadron also provided support in Mission Support and Flight Operations trades. In late 2012, it was announced that the Squadron would start recruiting for the RAF Police in 2013. Consequently, the Squadron has transitioned to primarily being an RAF Police unit, while still retaining a Flight of the RAF Regiment.

Sellafield, which was formerly known as Windscale Works, was an important multi-functional nuclear site located near Seascale on the coast of Cumbria, England. As of August 2022, its primary activities are the processing and storage of nuclear waste, along with decommissioning. Historically, the facility produced nuclear power from 1956 to 2003 and reprocessed nuclear fuel from 1952 to 2022. Originally built as a Royal Ordnance Factory in 1942, the site was briefly owned by Courtaulds for rayon production in the post-World War II years. Then in 1947, the Ministry of Supply reacquired it for plutonium production, leading to the construction of the Windscale Piles and the First-Generation Reprocessing Plant, and its renaming to “Windscale Works.” Significant developments followed, including the construction of Calder Hall, the world’s first commercial nuclear power station to supply electricity to a public grid, the Magnox fuel reprocessing plant, the prototype Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor (AGR), and the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (THORP). Decommissioning has been concentrated on the Windscale Piles, Calder Hall, and various historic reprocessing and waste storage facilities.

Sellafield, which was formerly known as Windscale Works, was an important multi-functional nuclear site located near Seascale on the coast of Cumbria, England. As of August 2022, its primary activities are the processing and storage of nuclear waste, along with decommissioning. Historically, the facility produced nuclear power from 1956 to 2003 and reprocessed nuclear fuel from 1952 to 2022. Originally built as a Royal Ordnance Factory in 1942, the site was briefly owned by Courtaulds for rayon production in the post-World War II years. Then in 1947, the Ministry of Supply reacquired it for plutonium production, leading to the construction of the Windscale Piles and the First-Generation Reprocessing Plant, and its renaming to “Windscale Works.” Significant developments followed, including the construction of Calder Hall, the world’s first commercial nuclear power station to supply electricity to a public grid, the Magnox fuel reprocessing plant, the prototype Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor (AGR), and the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (THORP). Decommissioning has been concentrated on the Windscale Piles, Calder Hall, and various historic reprocessing and waste storage facilities.

During its “Windscale Works” years, a severe fire broke out in the core of a nuclear reactor on October 10, 1957. As a result, significant radioactive material was released into the environment on October 10-11, 1957. Windscale Works was under the operation of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) at the time. On the 15th of October, the UKAEA Chairman announced the formation of an Inquiry Committee, chaired by Sir William Penney, to investigate the incident. The Committee convened at  Windscale Works from October 17–25th. They interviewed 37 individuals and reviewed 73 technical exhibits. They submitted their findings to the UKAEA Chairman on 26th October. These findings underpinned a UK Government White Paper (Command Paper 302), published on November 8, 1957. Oddly or perhaps criminally, the Penney Report itself remained unpublished until it was made available at The National Archives, Kew, in January 1988, basically covering up the event for decades. This event transpired when uranium metal fuel caught fire within Windscale Pile No. 1. The fire led to the release of radioactive contamination into the environment, which is estimated to have eventually caused approximately 240 cancer cases, with fatalities between 100 to 240. The incident received a level 5, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The maximum rating is 7.

Windscale Works from October 17–25th. They interviewed 37 individuals and reviewed 73 technical exhibits. They submitted their findings to the UKAEA Chairman on 26th October. These findings underpinned a UK Government White Paper (Command Paper 302), published on November 8, 1957. Oddly or perhaps criminally, the Penney Report itself remained unpublished until it was made available at The National Archives, Kew, in January 1988, basically covering up the event for decades. This event transpired when uranium metal fuel caught fire within Windscale Pile No. 1. The fire led to the release of radioactive contamination into the environment, which is estimated to have eventually caused approximately 240 cancer cases, with fatalities between 100 to 240. The incident received a level 5, on the International Nuclear Event Scale. The maximum rating is 7.

Now called Sellafield, the licensed premises span 650 acres, housing over 200 nuclear facilities and more than 1,000 buildings. It stands as the largest nuclear site in Europe, boasting the world’s most varied array of nuclear facilities on a single site. Workforce numbers fluctuate, but prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the site  employed around 10,000 individuals. The Central Laboratory and headquarters of the UK’s National Nuclear Laboratory are located on the premises. The site is owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), a non-departmental public body of the UK government. From 2008 to 2016, it was managed by a private consortium before control reverted to the government. Consequently, the Site Management Company, Sellafield Ltd, became a subsidiary of the NDA. The decommissioning process of the legacy facilities, which includes structures from the UK’s early efforts to develop an atomic bomb, is expected to be completed by 2120 at an estimated cost of £121 billion.

employed around 10,000 individuals. The Central Laboratory and headquarters of the UK’s National Nuclear Laboratory are located on the premises. The site is owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), a non-departmental public body of the UK government. From 2008 to 2016, it was managed by a private consortium before control reverted to the government. Consequently, the Site Management Company, Sellafield Ltd, became a subsidiary of the NDA. The decommissioning process of the legacy facilities, which includes structures from the UK’s early efforts to develop an atomic bomb, is expected to be completed by 2120 at an estimated cost of £121 billion.