World War II

During World War II and really with any war, any coastal area of the United States had to be kept on a higher alert than during peacetime. Coastal defense networks now are much more technological that they were in 1943. During World War II, the West Coast was patrolled by units of men whose job it was to watch for activities that were out of the ordinary along the Olympic Coast of Washington. Normally, their job was pretty boring, unless you liked walking or driving along the coast looking at the ocean. There were ships out there, but most of them were where they were supposed to be and were not cause for concern.

During World War II and really with any war, any coastal area of the United States had to be kept on a higher alert than during peacetime. Coastal defense networks now are much more technological that they were in 1943. During World War II, the West Coast was patrolled by units of men whose job it was to watch for activities that were out of the ordinary along the Olympic Coast of Washington. Normally, their job was pretty boring, unless you liked walking or driving along the coast looking at the ocean. There were ships out there, but most of them were where they were supposed to be and were not cause for concern.

In the early spring of 1943, however, coastal lookout activities along the Olympic Peninsula suddenly took a turn from the mundane to something quite unusual. As the La Push unit patrolled the beach that day, they suddenly began to see debris on the beach. That is never a good thing to see, because it means that somewhere, there is a ship in a lot of trouble. Rain, wind, and heavy seas just before midnight on April 1st, were driving the Russian steamship Lamut toward the shoreline, and behind a jagged cluster of rocks just off Teahwhit Head. By the early morning hours of April 2nd, the ship was in great peril, and the lives of the crew hung in the balance.

The La Push patrol unit was in for an intense morning, as they would find at first light on April 2nd. When the  patrolmen began finding wreckage on the beach, they headed south along the beach to see if they might find the ship in trouble. It wasn’t long before they sighted part of the grounded ship. It was lodged between a hundred-foot cliff and a small, jagged rock island. Amazingly, there were survivors huddled high on the steeply sloping deck of the Russian ship called Lamut. They wouldn’t have lasted long on that deck, but the high seas made a sea rescue impossible. The coast guardsmen of the La Push Unit decided to attempt a rescue by land. That would be pretty treacherous in itself, but they had no other choice.

patrolmen began finding wreckage on the beach, they headed south along the beach to see if they might find the ship in trouble. It wasn’t long before they sighted part of the grounded ship. It was lodged between a hundred-foot cliff and a small, jagged rock island. Amazingly, there were survivors huddled high on the steeply sloping deck of the Russian ship called Lamut. They wouldn’t have lasted long on that deck, but the high seas made a sea rescue impossible. The coast guardsmen of the La Push Unit decided to attempt a rescue by land. That would be pretty treacherous in itself, but they had no other choice.

This would not be a quick rescue. By mid-morning, the members of the rescue party had cut a path through the thick underbrush bordering the beach. Then, they began their ascent along the slippery boulders to the top of the cliff above the smashed ship. They would have to get very creative in their rescue maneuvers. “Using gauze bandage weighted with a rock, a light line was lowered to the eager hands of the stranded crew aboard the Lamut. Tying heavier line to the gauze, one line succeeded another until a lifeline strong enough to support the weight of a single person was stretched between the ship and the cliff. One by one survivors were raised to the cliff top and finally assisted down the landward side of the rocky ridge to the beach below. As darkness approached, the last of the Lamut survivors emerged from the swampy beach trail to waiting coast guard trucks and ambulances.” The rescue of the Lamut crew was among the most dramatic events in the annals of World War II beach patrol history.

While this was just one of the rescues conducted by the Olympic Defense Network, it was undoubtedly the most intense rescue they performed in their years of service. On March 29, 1944, the beach patrol ended and a week

later the unit decommissioned. The trails in that area are now a part of the Olympic National Park probably date from the era of World War II beach patrol activities. A while back, a small, collapsed wood frame cabin was located at Teahwhit Head. It is believed to be associated with World War II beach patrolling activities in the La Push unit, and quite possibly belongs to the Lamut.

later the unit decommissioned. The trails in that area are now a part of the Olympic National Park probably date from the era of World War II beach patrol activities. A while back, a small, collapsed wood frame cabin was located at Teahwhit Head. It is believed to be associated with World War II beach patrolling activities in the La Push unit, and quite possibly belongs to the Lamut.

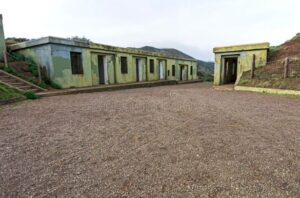

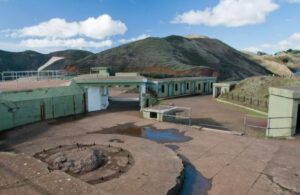

Battery Spencer was a reinforced concrete Endicott Period 12-inch gun battery, which was located on Fort Baker, Lime Point, Marin County, California. The structure still exists today and is a favorite tourist attraction. The battery was named on Feb 14, 1902, after Major General Joseph Spencer, who was a Revolutionary War hero. Spencer died on January 13, 1789. Construction on the battery began in 1893, and it was completed in 1897. Following its completion, it was transferred to the Coast Artillery for use on September 24, 1897, at a total cost of $110,352.70. It was deactivated in 1942 during World War II.

Battery Spencer was a reinforced concrete Endicott Period 12-inch gun battery, which was located on Fort Baker, Lime Point, Marin County, California. The structure still exists today and is a favorite tourist attraction. The battery was named on Feb 14, 1902, after Major General Joseph Spencer, who was a Revolutionary War hero. Spencer died on January 13, 1789. Construction on the battery began in 1893, and it was completed in 1897. Following its completion, it was transferred to the Coast Artillery for use on September 24, 1897, at a total cost of $110,352.70. It was deactivated in 1942 during World War II.

The battery was originally part of the Harbor Defense of San Francisco. The harbor was likely one of the most vulnerable entrances to San Fransisco, and in the early days of the country, when radar didn’t exist, it was hard to tell if an enemy was sneaking into the harbor, especially a submarine. Battery Spencer was a concrete coastal gun battery with three M1888 12-inch guns mounted on long range Barbette M1892 carriages. It was constructed on top of the five front emplacements of Battery Ridge. Back in the early 1900s, Battery Spencer was one of the main protection points for the San Francisco Bay. It featured multiple lookout points that were operated by the military and a few buildings for housing the generators and shells. It was used on and off until World War II when a lot of it was scrapped for war efforts.

The guns were mounted on 3 emplacements. Emplacements #1 and #2 were separated by a magazine with two shell rooms, a powder room, and a shell hoist room. Emplacement #3 had its own shell room, powder room, and hoist room. Spencer Battery was a two-story battery with the magazines on the lower level and the gun emplacements on the upper level. The missiles, or more likely cannon balls at first, were originally moved from the magazine level to the loading level with hand powered projectile hoists. In 1908, the hand powered hoists were replaced with electric Taylor-Raymond front delivery hoists. The new hoists were put into service on September 30, 1908. There were no powder hoists at Battery Spencer, meaning that gun powder had to be moved by hand.

Along the access road that runs north of Emplacement #1, was the BC Post and a separate building that had four rooms. The rooms consisted of a CO room, a guard room, an oil room, and a large 12′ by 43′ plotting room. All of these were used to plan any defensive action taken by the soldiers stationed at Battery Spencer. Two other buildings across the road completed the battery. One housed the tools and rammers, the other a latrine building with separate facilities for officers and enlisted. In 1910 the BC post and the plotting room were remodeled and updated. The work was accepted for service on August 5, 1910, at a cost of $1680.68.

When the United States entered World War I, it was decided that the large caliber coastal defense gun tubes should be removed from coastal batteries and sent into service in Europe. First, they were sent to arsenals for modification and mounting on mobile carriages, both wheeled and railroad. Strangely, most of the removed gun tubes never made it to Europe. Many were either remounted at the batteries or remained at the arsenals until needed elsewhere. One gun was removed from Battery Spencer emplacement #3 in 1918 and sent to Battery Chester at Fort Miley. The gun at Battery Spencer was never replaced, and the emplacement was considered abandoned. The carriage remained in place until it was ordered salvaged on January 10, 1927. World War II brought the first large scale scrap drive, and the remaining two guns and carriages were ordered scrapped on November 19, 1942.

These days Battery Spencer is part of the Golden Gate Recreation Area (GGNRA) administered by the National Park Service. It is a favorite historical attraction, even though no period guns or carriages are in place. The site is also one of the very best views of the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco.

The taking of vital ground is an important, if not essential part of war. In World War II, Iwo Jima was vital ground. It was prime real estate on which to build airfields to launch bombing raids against Japan, just 660 miles away. The Japanese had it, and the Americans needed it. So, they devised a plan to evict the, then current occupiers, so they could have it. The planned attack was called Operation Detachment, and the plan was to invade Iwo Jima thus putting the Allies in a better position to attack Japan.

The taking of vital ground is an important, if not essential part of war. In World War II, Iwo Jima was vital ground. It was prime real estate on which to build airfields to launch bombing raids against Japan, just 660 miles away. The Japanese had it, and the Americans needed it. So, they devised a plan to evict the, then current occupiers, so they could have it. The planned attack was called Operation Detachment, and the plan was to invade Iwo Jima thus putting the Allies in a better position to attack Japan.

The problem was that Iwo Jima was well fortified, both above and below ground…with a force that was 21,000 strong. The US Marines had to find out where the Japanese strongholds were on the island, so the invasion would take place is several phases. The United States had to be patient in the days leading up to the actual invasion, but they also had to apply pressure to keep the Japanese off guard.

To apply pressure, the Americans began bomber raids using B-24 and B-25 bombers in June 1944. The raids continued for 74 days. It was the longest pre-invasion bombardment of the war. Anytime bombing continues for that long, it has to be stressful for those in the bomb zone. The constant threat of falling bombs, and never knowing if they will land on you next, would make every day stressful. The bombing was necessary because of the extent to which the Japanese fortification of the island, above and below ground, including a network of caves.

Next came the Frogmen phase. “Frogmen” or Underwater Demolition Teams were dispatched by the Americans just before the actual invasion. The plan was to for the frogmen to draw fire from the Japanese, thus giving away many of their “secret” gun positions. Of course, as you can imagine, this was basically a suicide mission for the Underwater Demolition Teams. The amphibious landings of Marines began the morning of February 19, 1945, as the secretary of the navy, James Forrestal, accompanied by journalists, surveyed the scene from a command ship offshore. As the Marines made their way onto the island, seven Japanese battalions opened fire on them. By evening, more than 550 Marines were dead and more than 1,800 were wounded. It took four more days and many more casualties to capture of Mount Suribachi, the highest point of the island and bastion of the Japanese defense. While the taking of Iwo Jima was vital and those who fought and died there willingly gave

their lives for it, I have to think that it was a bittersweet victory, because of so many lives lost. Much like the D-Day storming of the beaches of Normandy, Iwo Jima was a suicide mission that was vital to the outcome of the war. The photo of the raising of the American flag on Iwo Jima, won the Pulitzer Prize for the photographer who took it, but I’m sure it was a photograph he would rather not have taken, considering the loss of life.

their lives for it, I have to think that it was a bittersweet victory, because of so many lives lost. Much like the D-Day storming of the beaches of Normandy, Iwo Jima was a suicide mission that was vital to the outcome of the war. The photo of the raising of the American flag on Iwo Jima, won the Pulitzer Prize for the photographer who took it, but I’m sure it was a photograph he would rather not have taken, considering the loss of life.

On October 31, 1922, following the March on Rome, Benito Mussolini was appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III. With that appointment, he became the youngest individual to hold the office up to that time. Mussolini quickly got to work, removing all political opposition through his secret police and outlawing labor strikes. He, along with his followers consolidated power through a series of laws that transformed Italy into a one-party dictatorship. A short five years later, he had established dictatorial authority by both legal and illegal means and planned to create a totalitarian state.

On October 31, 1922, following the March on Rome, Benito Mussolini was appointed prime minister by King Victor Emmanuel III. With that appointment, he became the youngest individual to hold the office up to that time. Mussolini quickly got to work, removing all political opposition through his secret police and outlawing labor strikes. He, along with his followers consolidated power through a series of laws that transformed Italy into a one-party dictatorship. A short five years later, he had established dictatorial authority by both legal and illegal means and planned to create a totalitarian state.

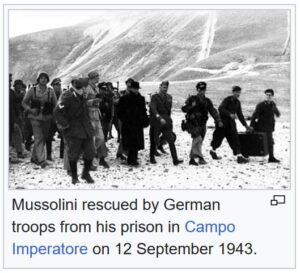

Still, as often happens, the people, good government officials, and of course, God made it clear that both fascist Italy and its dictator Benito Mussolini’s days were numbered by July 1943. So, after the successful Allied invasion of Sicily, the Italian government’s Grand Council delivered Mussolini a vote of no confidence. Shortly after that, King Vittorio Emanuele III replaced Mussolini as prime minister, and immediately had him arrested.

When Adolf Hitler heard of Mussolini’s arrest, he was furious. Hitler considered Mussolini to be his most powerful European ally, and Hitler began to make plans to rescue Mussolini. He brought in SS Major Otto Skorzeny, who was considered “the most dangerous man in Europe,” for the rescue mission. The Germans had  discovered that Mussolini was being held in a mountain ski resort 7,000 feet above sea level in the Abruzzo region. Due to the remoteness of the location, Skorzeny decided the only way to rescue Mussolini was to send in a dozen gliders with 108 commandos to do the job. The mission, dubbed Operation Eiche commenced on September 12, 1943. Along with the commandos, Skorzeny brought along an Italian general named Soleti. It was Soleti’s mission to create confusion among Mussolini’s guards, thereby giving the commandos time to get to Mussolini. While Soleti shouted orders at the confused guards, the commandos recaptured Mussolini without incident and flew him to a nearby Luftwaffe airfield, then to Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair headquarters in East Prussia.

discovered that Mussolini was being held in a mountain ski resort 7,000 feet above sea level in the Abruzzo region. Due to the remoteness of the location, Skorzeny decided the only way to rescue Mussolini was to send in a dozen gliders with 108 commandos to do the job. The mission, dubbed Operation Eiche commenced on September 12, 1943. Along with the commandos, Skorzeny brought along an Italian general named Soleti. It was Soleti’s mission to create confusion among Mussolini’s guards, thereby giving the commandos time to get to Mussolini. While Soleti shouted orders at the confused guards, the commandos recaptured Mussolini without incident and flew him to a nearby Luftwaffe airfield, then to Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair headquarters in East Prussia.

While Mussolini was free now, this would not be the victory Mussolini had hoped for. The Germans installed Mussolini as the head of a puppet regime called the Italian Socialist Republic in the town of Salo. The position wasn’t much more than symbolic. The German press portrayed the rescue as a daring feat of bravery…at the time, but in 2016, Italian author Vincenzo Di Michele researched the raid and concluded that it was likely enabled by Mussolini sympathizers in the Italian government. Mussolini could not be allowed to be free, even to run a puppet regime, and so the Allies began their hunt for him. On April 25, 1945, Allied troops were advancing into northern Italy, and the collapse of the Salò Republic was imminent. Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci attempted to escape to Switzerland, intending to board a plane and escape to Spain. Two days later on April 27th, they were stopped near the village of Dongo (Lake Como) by communist partisans named

Valerio and Bellini and identified by the Political Commissar of the partisans’ 52nd Garibaldi Brigade, Urbano Lazzaro. The next day, Mussolini and Petacci were both executed, along with most of the members of their 15-man train, primarily ministers and officials of the Italian Social Republic, in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra by a partisan leader who used the name de guerre Colonnello Valerio (Not his real name, his real name remains unknown.)

Valerio and Bellini and identified by the Political Commissar of the partisans’ 52nd Garibaldi Brigade, Urbano Lazzaro. The next day, Mussolini and Petacci were both executed, along with most of the members of their 15-man train, primarily ministers and officials of the Italian Social Republic, in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra by a partisan leader who used the name de guerre Colonnello Valerio (Not his real name, his real name remains unknown.)

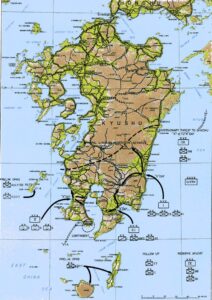

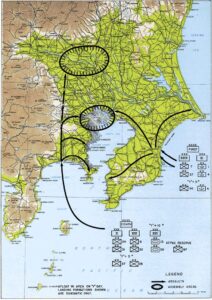

Near what is now known to be the end of World War II, a plan was devised to invade the Japanese home islands. In the end, Operation Downfall was not carried out, because Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet declaration of war, and the invasion of Manchuria. Nevertheless, in the days and months leading up to the planned attack, with its two parts…Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet, the United States Armed Forces ordered 1 million Purple Heart medals, in anticipation of a bloody battle. Operation Olympic was set to begin in November 1945, and was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost

Near what is now known to be the end of World War II, a plan was devised to invade the Japanese home islands. In the end, Operation Downfall was not carried out, because Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet declaration of war, and the invasion of Manchuria. Nevertheless, in the days and months leading up to the planned attack, with its two parts…Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet, the United States Armed Forces ordered 1 million Purple Heart medals, in anticipation of a bloody battle. Operation Olympic was set to begin in November 1945, and was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost  main Japanese island, Kyushu, with the recently captured island of Okinawa to be used as a staging area. The second attack was planned for early 1946. Operation Coronet was supposed to be the invasion of the Kanto Plain, near Tokyo, on the main Japanese island of Honshu. Important airbases on Kyushu that would be captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet. If Downfall had taken place, it would have been the largest amphibious operation in history…even surpassing D-Day.

main Japanese island, Kyushu, with the recently captured island of Okinawa to be used as a staging area. The second attack was planned for early 1946. Operation Coronet was supposed to be the invasion of the Kanto Plain, near Tokyo, on the main Japanese island of Honshu. Important airbases on Kyushu that would be captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet. If Downfall had taken place, it would have been the largest amphibious operation in history…even surpassing D-Day.

This planned set of attacks was no mystery to Japan either, because their geography made this invasion plan quite obvious. The Japanese were able to accurately predict the Allied invasion plans, and they adjusted their defensive plan, known as Operation  Ketsugo, accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyushu, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations. Casualty predictions varied widely, but they were expected to be extremely high. Depending on the degree to which Japanese civilians would have resisted the invasion, estimates ran up into the millions for Allied casualties. No wonder the United States expected to need 1 million Purple Heart medals. Thankfully, those millions of Allied casualties never materialized, because when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war ended. The United States was left with 1 million Purple Heart medals, which they are still using today. I think that while having 1 million Purple Heart medals isn’t the worst thing ever, just the fact that we still have some of those 1 million Purple Heart medals means that, in some way, we have kept some of our soldiers safe over the years. I don’t know how many are left, but it doesn’t matter, because at this point, 78 years later…there are some left.

Ketsugo, accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyushu, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations. Casualty predictions varied widely, but they were expected to be extremely high. Depending on the degree to which Japanese civilians would have resisted the invasion, estimates ran up into the millions for Allied casualties. No wonder the United States expected to need 1 million Purple Heart medals. Thankfully, those millions of Allied casualties never materialized, because when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war ended. The United States was left with 1 million Purple Heart medals, which they are still using today. I think that while having 1 million Purple Heart medals isn’t the worst thing ever, just the fact that we still have some of those 1 million Purple Heart medals means that, in some way, we have kept some of our soldiers safe over the years. I don’t know how many are left, but it doesn’t matter, because at this point, 78 years later…there are some left.

What would make a tiny nation try to invade a nation that is more that 25 times larger, with a population that is at least 8 times larger? It makes no sense, and yet on February 15, 1937, Japan attempted to invade China. Japan, with a total of 60,000 soldiers enter Northern China using planes and tanks. The invasion was something they had studied so they would have a plan before they attempted such an outlandish scheme. The type of conquest they were trying to mimic was that of Kubia Kahn, the Mongol emperor, who in 1271, established the Yuan dynasty and formally claimed orthodox succession from prior Chinese dynasties. The Yuan dynasty came to rule over most of present-day China, Mongolia, Korea, southern Siberia, and other adjacent areas. Kahn also amassed influence in the Middle East and Europe as khagan. By 1279, the Yuan conquest of the Song dynasty was completed, and Kahn became the first non-Han emperor to rule all of China proper.

What would make a tiny nation try to invade a nation that is more that 25 times larger, with a population that is at least 8 times larger? It makes no sense, and yet on February 15, 1937, Japan attempted to invade China. Japan, with a total of 60,000 soldiers enter Northern China using planes and tanks. The invasion was something they had studied so they would have a plan before they attempted such an outlandish scheme. The type of conquest they were trying to mimic was that of Kubia Kahn, the Mongol emperor, who in 1271, established the Yuan dynasty and formally claimed orthodox succession from prior Chinese dynasties. The Yuan dynasty came to rule over most of present-day China, Mongolia, Korea, southern Siberia, and other adjacent areas. Kahn also amassed influence in the Middle East and Europe as khagan. By 1279, the Yuan conquest of the Song dynasty was completed, and Kahn became the first non-Han emperor to rule all of China proper.

So, with dreams of power and world domination, among other things, including a need for the resources Japan lacked and China had, the Japanese army under Emperor Hirohito made the decision to attack the much larger  and more populated China. They threatened to bottle up 400,000 Chinese people on China’s central front. The attack area was approximately 20 miles, from the Yellow River to the Henan Capital provincial (Kaifeng). The Japanese Army displayed far superior air power and many more combat troops during the Japanese onslaught. In fact, their might could easily be called terrifying. China was helpless at stopping the Japanese forces from occupying Shanghai, and they were barely able prevent the invasion of Japan on the capital. The Chinese desperately tried to fight back with small caliber weapons against the heavy artillery fire power, air and naval might, and armored defenses of Japan. While they were severely outgunned, the bravery, stubbornness and determination of the Chinese made it possible for the country to withstand three months of defending Shanghai. Nevertheless, in the end, Shanghai fell, and Japan gained control over the city. The best of China’s troops were defeated. Still, the Japanese were surprised at the length of time that the Chinese troops were able to make a stand for their capital city. Because of their military superiority, the Japanese fully expected a short battle and a swift victory. They were not prepared for the one variable…the determination of the Chinese

and more populated China. They threatened to bottle up 400,000 Chinese people on China’s central front. The attack area was approximately 20 miles, from the Yellow River to the Henan Capital provincial (Kaifeng). The Japanese Army displayed far superior air power and many more combat troops during the Japanese onslaught. In fact, their might could easily be called terrifying. China was helpless at stopping the Japanese forces from occupying Shanghai, and they were barely able prevent the invasion of Japan on the capital. The Chinese desperately tried to fight back with small caliber weapons against the heavy artillery fire power, air and naval might, and armored defenses of Japan. While they were severely outgunned, the bravery, stubbornness and determination of the Chinese made it possible for the country to withstand three months of defending Shanghai. Nevertheless, in the end, Shanghai fell, and Japan gained control over the city. The best of China’s troops were defeated. Still, the Japanese were surprised at the length of time that the Chinese troops were able to make a stand for their capital city. Because of their military superiority, the Japanese fully expected a short battle and a swift victory. They were not prepared for the one variable…the determination of the Chinese  people. Morale plummeted over the heavy losses incurred, but not for long.

people. Morale plummeted over the heavy losses incurred, but not for long.

I sometimes wonder if these heads of governments really think that they can somehow control the world, or even, if they really think they can control the country they have invaded. The main reasons that nations and borders change as often as they do, is that people will only live under oppression for so long. Then, they will fight back. As to the heads of nations and ruling the world. While they might be the “head” of their nation, in a situation of world domination, I seriously doubt if any of these national leaders would be the one in control.

Over the years, many people have collected postcards. Some like them for the scenic views, and some collect postcards that have been sent to them, saving them as mementos of family members who won’t always be with us. I have picked up lots of postcards for my sister, Cheryl Masterson, who has a collection. While this is a cool way to get great pictures of amazing places, postcards were once used as…intel.

Over the years, many people have collected postcards. Some like them for the scenic views, and some collect postcards that have been sent to them, saving them as mementos of family members who won’t always be with us. I have picked up lots of postcards for my sister, Cheryl Masterson, who has a collection. While this is a cool way to get great pictures of amazing places, postcards were once used as…intel.

Starting in 1942, as the BBC, as part of their planning of the D-Day attack, issued a public appeal for postcards and photographs of mainland Europe’s coast, from Norway to the Pyrenees. The British people were eager to help and began sending in postcards and pictures from their trips to France. Other families began searching through boxes of family photos, searching for anything that might show the beaches. Photos of kids building  sandcastles, and people lounging on the beach flooded the BBC offices. While it all seemed like a fun project, the people had no idea that their family photographs would prove very instrumental in the D-Day landings. Within 36 hours, over 30,000 packs of pictures of the French coast arrived at the BBC offices. Even more incredible was the fact that by 1944, 10 million holiday snaps and postcards, hotel brochures, letters and guidebooks had arrived by post. Once there, the postcards and photographs were sorted, and the best ones were pinned to a board in a top-secret planning room. Then the army bosses began to study every inch of the beaches and landing areas where the Normandy invasion would go on to take on June 6, 1944.

sandcastles, and people lounging on the beach flooded the BBC offices. While it all seemed like a fun project, the people had no idea that their family photographs would prove very instrumental in the D-Day landings. Within 36 hours, over 30,000 packs of pictures of the French coast arrived at the BBC offices. Even more incredible was the fact that by 1944, 10 million holiday snaps and postcards, hotel brochures, letters and guidebooks had arrived by post. Once there, the postcards and photographs were sorted, and the best ones were pinned to a board in a top-secret planning room. Then the army bosses began to study every inch of the beaches and landing areas where the Normandy invasion would go on to take on June 6, 1944.

The families who sent in their family photographs and postcards, had no idea what would come of their contribution. They weren’t told why their pictures were needed, just that it was an important project. Looking at the photographs now, the innocent snaps almost bring a feeling of deep sadness. Nevertheless, the photographs and postcards were instrumental and extremely important to the war effort. After looking at all the

pictures, it was decided that the best place to carry out their plan was on the beaches at Normandy, France. Many of these postcards were used in briefings with officers, land craft operators and other infantry soldier to study and orient themselves based on their drop locations of the building and landmarks in these photos. Of course, the rest is history, and the operation to storm the beaches at Normandy was a great success.

pictures, it was decided that the best place to carry out their plan was on the beaches at Normandy, France. Many of these postcards were used in briefings with officers, land craft operators and other infantry soldier to study and orient themselves based on their drop locations of the building and landmarks in these photos. Of course, the rest is history, and the operation to storm the beaches at Normandy was a great success.

Once upon a time, journalists and the media as a whole had an obligation to tell the truth, or at least tell the public that the story was their opinion only. The had to have reliable sources, even if they didn’t have to disclose them. While they weren’t “forced” to be truthful, they were completely shunned if they didn’t.

Once upon a time, journalists and the media as a whole had an obligation to tell the truth, or at least tell the public that the story was their opinion only. The had to have reliable sources, even if they didn’t have to disclose them. While they weren’t “forced” to be truthful, they were completely shunned if they didn’t.

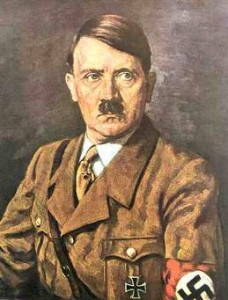

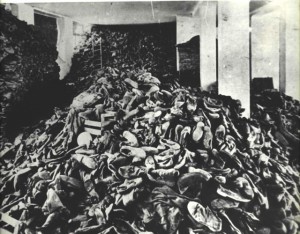

When a journalist is mesmerized by someone, they can definitely fall hard for them. Such was the case with “the job-creating Führer with eyes that were like ‘blue larkspur.'” Why did so many journalists spend years dismissing the evidence of Hitler’s atrocities? Some, like the Christian Science Monitor called Hiter’s effect on Germany as providing “a dark land a clear light of hope.” They talked about how smoothly things were running, how well regulated everything was, and how great the police uniforms were. Strangely, when it came to the killing of the Jewish people, they said things like, “I have so far found quietness, order, and civility;” there was “not the slightest sign of anything unusual afoot.” As for all those “harrowing stories” of Jews being mistreated…they seemed to apply “only to a small proportion;” most were “not in any way molested.” They made it seem like as long as the number were “low,” the problem couldn’t possibly be a big one. Well, the reality as we all know now is that the “problem” was enormous, heinous, and horrific beyond imagination.

Trusting the journalists implicitly, without doing your own research is a very dangerous plan. Journalists have been known to assist in “hiding the evidence” in a matter…as we have seen in recent years. I don’t believe that all journalists are “bad” people, but those that are “bad” people ruin the reputation of journalism for every good journalist. I’m not even sure I would call some of the media, journalists. They are truly just “bad fiction writers,” in my opinion. Anyone who covers up the truth in the name of free speech or forces others to hide the truth in the name of tolerance is a bad journalist.

Many in the American mainstream newspaper industry portrayed the Hitler regime positively, especially in its

early months. Looking back now, we wonder how they could have said the good things they said about such a horrible dictator. The media published warm human-interest stories about Hitler, while simply excusing or rationalizing Nazi anti-Semitism. These actions should haunt the conscience of United States Journalism to this day. There was no excuse for what Hitler did, and to write it off as “not so bad” was absolutely inexcusable.

early months. Looking back now, we wonder how they could have said the good things they said about such a horrible dictator. The media published warm human-interest stories about Hitler, while simply excusing or rationalizing Nazi anti-Semitism. These actions should haunt the conscience of United States Journalism to this day. There was no excuse for what Hitler did, and to write it off as “not so bad” was absolutely inexcusable.

Of course, not all of the “bad journalism” of the day was sinister. Hitler was an unfamiliar subject when he first appeared on the international scene. His ideals and his movement were unknown, and so could have been mistaken for something quite innocent…at first. The Nazis had risen from barely 18 percent of the national vote in mid-1930 to become Germany’s largest party only two years later and gained power just months after that. I suppose that the political rise of Hitler could have just seemed like someone with great ideas stepping up to the microphone. It is thought that many American editors and reporters erroneously assumed, based on previous experience, that a radical candidate would show some restraint once in office, but that was not Hitler’s plan. He planned to take over the world…to become a One World Government. Really, any time anyone tries to take away the sovereignty of a country, they are not acting in the best interest of that country. That is something we must never forget.

An editorial in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin on January 30, 1933, asserted that “there have been indications of moderation” on Hitler’s part. The editors of The Cleveland Press, on January 31, 1933, claimed the

“appointment of Hitler as German chancellor may not be such a threat to world peace as it appears at first blush.” Frederick Birchall, Berlin bureau chief for The New York Times, found “a new moderation” in the political atmosphere following Hitler’s rise to power. Unfortunately, all of them were dead wrong!! Hitler was not a moderate. He was, in fact, more of a threat than they could ever have imagined. Hitler was the epitome of evil, and like it or not, any journalist who softened the story, was guilty of hiding the evidence.

“appointment of Hitler as German chancellor may not be such a threat to world peace as it appears at first blush.” Frederick Birchall, Berlin bureau chief for The New York Times, found “a new moderation” in the political atmosphere following Hitler’s rise to power. Unfortunately, all of them were dead wrong!! Hitler was not a moderate. He was, in fact, more of a threat than they could ever have imagined. Hitler was the epitome of evil, and like it or not, any journalist who softened the story, was guilty of hiding the evidence.

The ship that would eventually become the USS Serpens was built by California Shipbuilding Corporation in Wilmington, California. The ship was laid down March 10, 1943, as EC2 class Liberty Ship that was initially named SS Benjamin N. Cardozo (MCE hull 739). In the course of a little more than a month, SS Cardozo was transferred to the US Navy (USN) on April 19, 1943, and renamed USS Serpens (AK-97) after the star constellation Serpens. USS Serpens was commissioned May 28, 1943, at San Diego, and assigned to Captain Magnus J. Johnson, USCGR and manned by a crew from the US Coast Guard (USCG). From there, the ship led a relatively normal “life” for a ship. At least until the evening of January 29, 1945, when the USS Serpens (AK 97) was anchored off Lunga Beach, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Commander Perry L Stinson, and some of the enlisted men were ashore performing administrative functions.

The ship that would eventually become the USS Serpens was built by California Shipbuilding Corporation in Wilmington, California. The ship was laid down March 10, 1943, as EC2 class Liberty Ship that was initially named SS Benjamin N. Cardozo (MCE hull 739). In the course of a little more than a month, SS Cardozo was transferred to the US Navy (USN) on April 19, 1943, and renamed USS Serpens (AK-97) after the star constellation Serpens. USS Serpens was commissioned May 28, 1943, at San Diego, and assigned to Captain Magnus J. Johnson, USCGR and manned by a crew from the US Coast Guard (USCG). From there, the ship led a relatively normal “life” for a ship. At least until the evening of January 29, 1945, when the USS Serpens (AK 97) was anchored off Lunga Beach, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. The Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Commander Perry L Stinson, and some of the enlisted men were ashore performing administrative functions.

The remaining 970 crew members were loading depth charges when the USS Serpens suddenly exploded, leaving only the bow of the ship visible. The explosion was devastating, and only two sailors aboard…SN 1/C Kelsie K Kemp and SN 1/C George S Kennedy survived by clinging to the bow section of the ship, after escaping  from the “bosun’s hole” inside the ship. The rest of the crew consisting of 198 Coast Guardsmen, 56 US Army stevedores, and Dr Levin, a US Public Health Service surgeon, died…most instantly. Of the 198 US Coast Guardsmen, 167 were reservists. In the immense explosion, nearby ships were damaged, and a US Army soldier on the beach was killed. The loss of the USS Serpens remains the largest single disaster ever suffered by the Coast Guard.

from the “bosun’s hole” inside the ship. The rest of the crew consisting of 198 Coast Guardsmen, 56 US Army stevedores, and Dr Levin, a US Public Health Service surgeon, died…most instantly. Of the 198 US Coast Guardsmen, 167 were reservists. In the immense explosion, nearby ships were damaged, and a US Army soldier on the beach was killed. The loss of the USS Serpens remains the largest single disaster ever suffered by the Coast Guard.

An eyewitness account of the disaster stated that, “As we headed our personnel boat shoreward the sound and concussion of the explosion suddenly reached us, and, as we turned, we witnessed the awe-inspiring death drams unfold before us. As the report of screeching shells filled the air and the flash of tracers continued, the water splashed throughout the harbor as the shells hit. We headed our boat in the direction of the smoke and as we came into closer view of what had once been a ship, the water was filled only with floating debris, dead fish, torn life jackets, lumber and other unidentifiable objects. The smell of death, and fire, and gasoline, and oil was evident and nauseating. This was sudden death, and horror, unwanted and unasked for, but complete.”

The Coast Guard initially though the explosion was an enemy attack. They actually continued to think that until  July 1947. By June 10, 1949, it was officially determined not to have been the result of enemy attack. Unfortunately, there would be no real answers as to what happened. The remains of the 250 men who lost their lives were originally buried at the Army, Navy, and Marine Cemetery in Guadalcanal with full military honors and religious services. Later, however, the remains were repatriated under the program for the return of World War II dead in 1949. The mass recommittal of the 250 unidentified dead took place in section 34 at MacArthur Circle, Arlington National Cemetery. The remains were placed in 52 caskets and buried in 28 graves near the intersection of Jesup and Grant Drives. The two survivors both earned the Purple Heart injuries sustained.

July 1947. By June 10, 1949, it was officially determined not to have been the result of enemy attack. Unfortunately, there would be no real answers as to what happened. The remains of the 250 men who lost their lives were originally buried at the Army, Navy, and Marine Cemetery in Guadalcanal with full military honors and religious services. Later, however, the remains were repatriated under the program for the return of World War II dead in 1949. The mass recommittal of the 250 unidentified dead took place in section 34 at MacArthur Circle, Arlington National Cemetery. The remains were placed in 52 caskets and buried in 28 graves near the intersection of Jesup and Grant Drives. The two survivors both earned the Purple Heart injuries sustained.

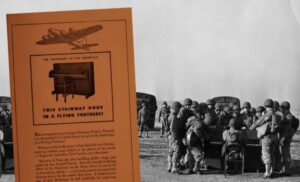

Production needs during wartime often change dramatically, and the piano industry was no exception. I suppose that such frivolous items as a piano, must go by the wayside when so many much more important things like weapons, military vehicles, and military airplanes were needed so much more. That is what you might logically think anyway. Nevertheless, you would be wrong. During World War II, the famous musical instrument company, Steinway and Sons, did stop making traditional pianos. The biggest reason for the change was because the materials they needed were shifted to the war effort. Still, the company didn’t shut down production entirely. They actually began making things that were needed for the war effort. Things like coffins and parts for military transports became the production like items of the day. It seemed a sad state of affairs for a company that had once brought so much joy and happiness to so many households and concert halls, but it had to be done, so they stepped up and did their part.

Production needs during wartime often change dramatically, and the piano industry was no exception. I suppose that such frivolous items as a piano, must go by the wayside when so many much more important things like weapons, military vehicles, and military airplanes were needed so much more. That is what you might logically think anyway. Nevertheless, you would be wrong. During World War II, the famous musical instrument company, Steinway and Sons, did stop making traditional pianos. The biggest reason for the change was because the materials they needed were shifted to the war effort. Still, the company didn’t shut down production entirely. They actually began making things that were needed for the war effort. Things like coffins and parts for military transports became the production like items of the day. It seemed a sad state of affairs for a company that had once brought so much joy and happiness to so many households and concert halls, but it had to be done, so they stepped up and did their part.

While they made many coffins and parts, strangely, Steinway was also contracted by the War Production Board  to make…pianos!! What?? The government wanted pians that could be set into battle, and when I think of shows like “MASH” with the piano that graced the “Officer’s Club,” that as it turned out, wasn’t just for officers, it makes perfect sense. What better way to boost moral than a piano that could be sent into battle. The new Steinway and Sons pianos were “small, sturdy uprights, painted olive drab and shipped by cargo vessels and transport planes to military theaters around the world.” Called “Victory Verticals” or “G.I. Steinways,” the company made about 3,000 of the pianos in 1942 and 1943. Some of the instruments were actually parachuted into camp complete with tuning tools and instructions. Now all it needed was a soldier who could play, and hopefully not just chop sticks. Others came in by Jeep on a wagon.

to make…pianos!! What?? The government wanted pians that could be set into battle, and when I think of shows like “MASH” with the piano that graced the “Officer’s Club,” that as it turned out, wasn’t just for officers, it makes perfect sense. What better way to boost moral than a piano that could be sent into battle. The new Steinway and Sons pianos were “small, sturdy uprights, painted olive drab and shipped by cargo vessels and transport planes to military theaters around the world.” Called “Victory Verticals” or “G.I. Steinways,” the company made about 3,000 of the pianos in 1942 and 1943. Some of the instruments were actually parachuted into camp complete with tuning tools and instructions. Now all it needed was a soldier who could play, and hopefully not just chop sticks. Others came in by Jeep on a wagon.

As the gifts made their strange arrivals, the men welcomed their arrival. Any camp that was blessed enough to receive a Victory Vertical felt an instant lift of their spirits. One US Army Private, Kenneth Kranes told his  mother in a letter home from North Africa dated May 6, 1943, “Two nights past we received welcome entertainment when a Jeep pulling a small wagon came to camp. The wagon contained a light system and a Steinway pianna. It is smaller and painted olive green, just like the Jeep. We all got a kick out of it and sure had fun after meals when we gathered around the pianna to sing. I slept smiling and even today am humming a few of the songs we sang.” Who would have thought that a company so famed for its elegant musical instruments would find that quite possibly its most famous instrument would be a plain-Jane, olive-drab version of what it expected to be famous for.

mother in a letter home from North Africa dated May 6, 1943, “Two nights past we received welcome entertainment when a Jeep pulling a small wagon came to camp. The wagon contained a light system and a Steinway pianna. It is smaller and painted olive green, just like the Jeep. We all got a kick out of it and sure had fun after meals when we gathered around the pianna to sing. I slept smiling and even today am humming a few of the songs we sang.” Who would have thought that a company so famed for its elegant musical instruments would find that quite possibly its most famous instrument would be a plain-Jane, olive-drab version of what it expected to be famous for.