World War II

In the United States, at least on American soil, World War II seemed so far away, but the reality is that in parts of the United States, including Wyoming, the war, or part of it was closer to home than we realized. In fact, it was as close as an hour away from where my mom’s family lived, in Casper, Wyoming. Of course, I don’t mean the fighting, but the area was still connected to World War II. In Douglas, Wyoming, there was an internment camp for Prisoners of War (POW) called Camp Douglas. The camp was used between January 1943 and February 1946 housing first Italian and then German prisoners of war in the United States. During 1942, the first year of United States involvement in World War II, an estimated 2000 prisoners came to the United States. The POW camps overseas were so overcrowded that by September they needed a place to take them, where they could safely be contained. In order to be prepared for the 50,000 POWs being held by the British in North Africa, the US needed to reactivate the Civilian Conservation Corps camps. They opened unused portions of several major military bases; utilizing such facilities as fairgrounds, racetracks, armories, and auditoriums; and setting up “tent cities” in remote areas of the country.

In the United States, at least on American soil, World War II seemed so far away, but the reality is that in parts of the United States, including Wyoming, the war, or part of it was closer to home than we realized. In fact, it was as close as an hour away from where my mom’s family lived, in Casper, Wyoming. Of course, I don’t mean the fighting, but the area was still connected to World War II. In Douglas, Wyoming, there was an internment camp for Prisoners of War (POW) called Camp Douglas. The camp was used between January 1943 and February 1946 housing first Italian and then German prisoners of war in the United States. During 1942, the first year of United States involvement in World War II, an estimated 2000 prisoners came to the United States. The POW camps overseas were so overcrowded that by September they needed a place to take them, where they could safely be contained. In order to be prepared for the 50,000 POWs being held by the British in North Africa, the US needed to reactivate the Civilian Conservation Corps camps. They opened unused portions of several major military bases; utilizing such facilities as fairgrounds, racetracks, armories, and auditoriums; and setting up “tent cities” in remote areas of the country.

In the fall of 1942, knowing that they would need a better plan, they began the longer-range $50 million-dollar program of POW camp construction. The government had decided that for security reasons, the camps needed be located in remote and isolated areas. They didn’t want any camps to be built within 170 miles of the east and west coasts; nor within a 150-mile-wide zone along the Canadian and Mexican borders. They also forbade locations near shipyards, munitions plants, and other vital wartime industries due to fears of sabotage. These regulations made the ideal site, according to the Army Corps of Engineers, an area of 350 acres of level and well-drained land located within five miles of a railroad and 500 feet from any public road. Wyoming and other rural states became the prime locations, hence Camp Douglas. Another reason for placing the POW camps in the United States, was that it also abided by the international Geneva Convention agreements, which were signed by 47 world powers in 1929, and defined treatment of enemy prisoners. The USA made a much greater attempt to live up to the pact than the Axis powers. According to interpretation by American military leaders, camps had to be constructed to the minimum standards of a regular military compound. That insured that the prisoners had adequate housing, food, and water to sustain life and in the end, they were treated so humanely, and after the war many of them would have loved to just stay here. Wyoming was not opposed to a POW camp within its borders, because the presence of a large POW camp would provide an economic boon to a state and the nearby communities so “Chambers of Commerce, businessmen, the Commerce and department, city mayors, and the state’s political leaders sought to secure the establishment of military installations” in Wyoming, according to historian TA Larson. These lobbying efforts resulted in the construction of a new air base at Casper, a large expansion at Cheyenne’s Fort FE Warren, and the selection of a site on the outskirts of the small town of Douglas as the location for a POW camp.

The Douglas site met the defense regulations and was quickly approved. It was located in Converse County within one mile of a rail line that passed through downtown Douglas. The 687-acre site sat above the banks of the North Platte River. The federal government acquired the land through condemnation, which brought about a legal battle in which the defendants were eventually awarded more money for their land than the government had initially proposed. The government was rather between a rock and a hard place. They wanted the contracts for the site. In December of 1942, government surveyors and engineers arrived in Douglas, fueling rumors of the proposed POW camp although the official announcement did not come until January of 1943. The low bid came from Peter Kiewit and Sons of Omaha, Nebraska, and the company set up operations in Douglas by February of 1943. Four to five hundred construction workers used the 4-H buildings on the state fairgrounds as dorms and a dining hall. The government contract specified the buildings be completed within 120 days. Kiewit and Sons actually finished the job in 95 days. “The officers’ quarters, clubhouse, and softball field were located at the north main entrance to the camp, outside the double rows of wired fencing (the inner fence was electrified) and guard towers that surrounded the rest of the complex. The hospital area and the troop barracks were built directly inside the fence. Beyond that, the prison complex was organized into three compounds, separated by wire electrified fencing, each with a capacity of approximately one thousand men. Auxiliary areas for prisoners included a large outdoor recreation area near the river, a softball field, and one football field. The camp also accommodated a variety of operational functions in buildings designed for the motor pool, a heating plant, warehouses, corrals, a K-9 dog unit, a sewage disposal plant, as well as a salvage yard and gravel pit.”

The influx of people prompted the Douglas mayor to urge local residents to rent any spare rooms in their houses to the incoming military personnel and their families as a housing crunch was inevitable in the town. The town leaders with the home front war effort quickly established a Service Men’s Center in the downstairs room of the Moose Lodge. Moose members cleaned and remodeled the room while the ladies of the lodge scrounged up furniture and curtains from local donations. It was a concerted effort to welcome the new facility and its personnel. The Moose Lodge basement became a popular hangout for servicemen with daily hours from 5pm until midnight and stayed open till 2am on Saturday nights. The Center was affiliated with the national USO organization during the final days of the war. The local newspaper focused on the anticipation and excitement of the arrival of the US Army coming to their town, especially the officers, which helped to downplay any apprehension people may have felt about having an enemy population one mile away that outnumbered the townsfolk. Because so many of Wyoming’s men, like many other states, were serving in the war, it was decided that the prisoners could fill in some of the gaps outside the camp. Wyoming was left with a critical shortage of agricultural labor. POWs provided the solution to the problem and performed many essential jobs related to agriculture. They harvested crops, whether it was cotton in the South or sugar beets and timber in Wyoming. Local ranchers and farmers formed a corporation, in anticipation of the much-needed prison labor. A manager was appointed to handle the governmental red tape involved in the contracting procedures.

The story of this POW camp is an important part of the history of the town of Douglas. While Camp Douglas is no longer in use, there are still a few remaining structures. The walls of the Officer’s Club were painted with murals by three of the Italian prisoners. They are beautiful murals that depict western life and folklore. They are now registered with the United States Department of the Interior National Park Service on the National Register of Historic Places.

The story of this POW camp is an important part of the history of the town of Douglas. While Camp Douglas is no longer in use, there are still a few remaining structures. The walls of the Officer’s Club were painted with murals by three of the Italian prisoners. They are beautiful murals that depict western life and folklore. They are now registered with the United States Department of the Interior National Park Service on the National Register of Historic Places.

Carole Lombard was a fierce patriot, and knew that her actor husband, Clark Gable wanted to get into the war. Lombard knew that Clark Gable was officer material. Still, at the time, he had other obligations, so he waited. That wait came to an end, a few months after Lombard was killed on January 16, 1942, when the plane on which she was a passenger, flew into a cliff. Lombard’s flight, TWA Flight 3 was a on a twin-engine Douglas DC-3-382 propliner, registration NC1946, operated by Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA). It was a scheduled domestic passenger flight from New York, New York, to Burbank, California, in the United States, via several stopovers including Las Vegas, Nevada. On January 16, 1942, at 7:20pm PST, just fifteen minutes after takeoff from Las Vegas Airport (now Nellis Air Force Base) bound for Burbank, the aircraft was destroyed when it crashed into a sheer cliff on Potosi Mountain. It was determined that n error in compass heading and the blackout of most of the beacons in the neighborhood of the accident made necessary by the war emergency caused the crash. Lombard, renowned for her roles in screwball comedies such as “My Godfrey” and “To Be or Not to Be,” and for her marriage to Gable was just 33 years old.

Carole Lombard was a fierce patriot, and knew that her actor husband, Clark Gable wanted to get into the war. Lombard knew that Clark Gable was officer material. Still, at the time, he had other obligations, so he waited. That wait came to an end, a few months after Lombard was killed on January 16, 1942, when the plane on which she was a passenger, flew into a cliff. Lombard’s flight, TWA Flight 3 was a on a twin-engine Douglas DC-3-382 propliner, registration NC1946, operated by Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA). It was a scheduled domestic passenger flight from New York, New York, to Burbank, California, in the United States, via several stopovers including Las Vegas, Nevada. On January 16, 1942, at 7:20pm PST, just fifteen minutes after takeoff from Las Vegas Airport (now Nellis Air Force Base) bound for Burbank, the aircraft was destroyed when it crashed into a sheer cliff on Potosi Mountain. It was determined that n error in compass heading and the blackout of most of the beacons in the neighborhood of the accident made necessary by the war emergency caused the crash. Lombard, renowned for her roles in screwball comedies such as “My Godfrey” and “To Be or Not to Be,” and for her marriage to Gable was just 33 years old.

Gable and Lombard met in 1932 during the filming of “No Man of Her Own.” At that time, Gable was beginning his as one of Hollywood’s top leading men, while Lombard was a talented comedic actress striving to prove herself in more serious roles. Both were married at the time. Gable was married to a wealthy Texas widow ten years his senior, and Lombard to actor William Powell. Initially, neither showed much interest in the other, but when they met again three years later, Lombard had divorced Powell, and Gable was separated from his wife. Their relationship then took a different turn. Much to the media’s delight, the new couple was open with their affection, calling each other Ma and Pa and exchanging quirky, expensive gifts. In early 1939, Gable’s wife finally granted him a divorce, and he married Lombard that April.

In January 1942, shortly after America’s entry into World War II, Howard Dietz, publicity director of MGM film studio, enlisted Lombard for a tour to sell war in her home state of Indiana. Gable, who had been asked to serve as the of the actors’ branch the wartime Hollywood Victory Committee, remained in Los Angeles, where he was set to begin filming “Somewhere I’ll Find You” with Lana Turner. Dietz advised Lombard to avoid airplane travel due to his fears about its reliability and safety, so she completed most of the trip by train, stopping at various locations en route to Indianapolis and raising approximately $2 million for the war effort.

It was a good trip, but Lombard was tired and didn’t want to wait for the train for the return trip. Instead, she boarded the TWA DC-3 in Las Vegas with her mother, Elizabeth Peters, and a group that included the MGM publicity agent Otto Winkler and 15 young Army pilots. Shortly after takeoff, the plane veered off course. Warning beacons that might have helped guide the pilot had been blacked out because of fears about Japanese bombers, and the plane smashed into a cliff near the top of Potosi Mountain. Search parties were able to retrieve Lombard’s body, and she was buried next to her mother at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, California, under a marker that read “Carole Lombard Gable.”

Overcome with grief and alone in the empty house he had shared with Lombard, Gable resorted to heavy drinking and struggled to complete his work on “Somewhere I’ll Find You.” He was consoled by concerned friends, including the actress, Joan Crawford. In August, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Gable decided to enlist in the US Army Air Force. He spent the of the war in the United Kingdom and flew several combat missions (including one to Germany), earning multiple decorations for his efforts. He would marry twice more, but upon his death in 1960, Gable was interred at Forest Lawn, next to Lombard…his one true love.

Gable’s military service was marked by his dedication to aviation and combat operations. He was assigned to the 351st Bombardment Group as B-17 Flying Fortress gunner bomber pilot. His service was characterized by a combination of flying combat missions and supporting morale efforts. One of Gable’s notable contributions during the war was his involvement in the production of a documentary titled “Combat America” (1943). The film, produced and narrated by Gable, aimed to document the experiences of American bomber crews and underscore the importance of the war effort. This documentary was a significant endeavor and demonstrated Gable’s commitment to promoting the Allied cause.

While it was distinguished, Gable’s military service was not without its challenges. He faced the dangers of

combat missions and experienced the stresses and hardships of war. He was not mollycoddled because he was an actor. Over there, he persevered to be “just one of the men.” Despite these challenges, he remained committed to his duties and earned the respect of his fellow servicemen. Major Clark Gable’s military career was marked by his bravery and dedication to the war effort. He received the Air Medal and the Distinguished Flying Cross. His personal life might have been in a shambles, but his wife would have been very proud of his service.

combat missions and experienced the stresses and hardships of war. He was not mollycoddled because he was an actor. Over there, he persevered to be “just one of the men.” Despite these challenges, he remained committed to his duties and earned the respect of his fellow servicemen. Major Clark Gable’s military career was marked by his bravery and dedication to the war effort. He received the Air Medal and the Distinguished Flying Cross. His personal life might have been in a shambles, but his wife would have been very proud of his service.

We have all seen war correspondents, and in fact we are used to being kept up to date on the happenings of a war. Of course, that wasn’t always the case. In the 18th and 19th centuries, journalists often accompanied the military units offering firsthand accounts that were frequently influenced by patriotism or propaganda. These early correspondents established the early foundation for the profession, concentrating mainly on significant battles and strategic developments. When you think about it, while their reports might have been colored for those reason, it still took an element of courage to put themselves in harm’s way like that.

We have all seen war correspondents, and in fact we are used to being kept up to date on the happenings of a war. Of course, that wasn’t always the case. In the 18th and 19th centuries, journalists often accompanied the military units offering firsthand accounts that were frequently influenced by patriotism or propaganda. These early correspondents established the early foundation for the profession, concentrating mainly on significant battles and strategic developments. When you think about it, while their reports might have been colored for those reason, it still took an element of courage to put themselves in harm’s way like that.

One of the early groups to be assigned to on planes was known as the Writing 69th. They were a group of eight American journalists who had to train as gunners to fly bomber missions over Germany with the US Eighth Air Force during World War II. The Writing 69th was christened by one of the 8th Air Force’s public relations officers, possibly Hal Leyshon or Joe Maher. The group also considered the names “The Flying Typewriters” or “Legion of the Doomed,” but in the end, the Writing 69th won the day. The Writing 69th included Walter Cronkite, Andy Rooney, Bigart, Robert Post, Paul Manning, Denton Scott, William Wade, and Gladwin Hill.

All of these reporters, all of whom accompanied the 8th Air Force, were required to undergo a rigorous training course in just one week. You might wonder why they needed to be trained, because they were just writers after all. Nevertheless, it was required that they be trained in a multitude of tasks, including how to shoot weapons, despite rules barring non-combatants from carrying a weapon into combat. The men were also trained on how to adjust to high altitudes, parachuting, and enemy identification.

The first and final mission for the Writing 69th occurred on February 26, 1943. A group of American B-24s and B-17s were dispatched to attack the Focke-Wulf aircraft factory in Bremen, Germany. However, due to overcast skies over Bremen, the bombing run had to be diverted to a secondary target, the submarine pens at Wilhelmshaven. Were it not for what happened on that mission, the Writing 69th might have gone on more missions. Of the eight journalists who comprised the Writing 69th, only six went on that fateful mission. They were Post, Cronkite, Rooney, Wade, Bigart, and Hill. Over Oldenburg, Germany, the American bomber group encountered German fighters. The B-24 carrying Robert Post was shot down and exploded in mid-air, killing eight Air crew members, and Post. The other aircraft were able to return safely, although Rooney’s plane

sustained some flak (anti-aircraft) damage. Post’s death effectively ended the days of reporters flying on bombing missions. Although others, including Scott and Manning, both of whom missed the Wilhelmshaven raid, did fly after this mission. Nevertheless, it was not nearly as widespread as it might have been had not Post been killed.

sustained some flak (anti-aircraft) damage. Post’s death effectively ended the days of reporters flying on bombing missions. Although others, including Scott and Manning, both of whom missed the Wilhelmshaven raid, did fly after this mission. Nevertheless, it was not nearly as widespread as it might have been had not Post been killed.

I never gave much thought to the journalists who worked as war correspondents, it always just seemed like a normal part of their jobs. Of course, I knew that they were in war zones, and that there could be danger, but somehow, I thought that there was like some “unwritten code” that kept the reporters safe. Of course, that idea was ridiculous, but looking from the protected distance of a television set, a world away, that was where I was.

I suppose someone had to be the one…the fighter who carried out the most missions of the war. For one thing he would be the one who was fortunate enough to survive all those missions, and he would have to be the one who didn’t just go home when he finished the required number of missions to be discharged from service. For World War II, that man was Donald James Matthew Blakeslee, who was an officer in the United States Air Force. His aviation career commenced as a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force, flying Spitfire aircraft during World War II. Then, he joined the Air Force Eagle Squadrons, before transferring to the United States Army Air Forces in 1942. He flew more combat missions against the Luftwaffe than any other American fighter pilot, and by end of the war, he was a triple flying ace credited with 15.5 aerial victories.

I suppose someone had to be the one…the fighter who carried out the most missions of the war. For one thing he would be the one who was fortunate enough to survive all those missions, and he would have to be the one who didn’t just go home when he finished the required number of missions to be discharged from service. For World War II, that man was Donald James Matthew Blakeslee, who was an officer in the United States Air Force. His aviation career commenced as a pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force, flying Spitfire aircraft during World War II. Then, he joined the Air Force Eagle Squadrons, before transferring to the United States Army Air Forces in 1942. He flew more combat missions against the Luftwaffe than any other American fighter pilot, and by end of the war, he was a triple flying ace credited with 15.5 aerial victories.

Blakeslee was born in Fairport Harbor, Ohio, on September 11, 1917. He developed an interest in flying early in life after observing the Cleveland Air Races as a boy. With money saved from his job the Diamond Alkali Company, he and a friend purchased a Piper J-3 in the mid-1930s and flew it from Willoughby Field, Ohio. However, his friend crashed the plane in 1940, prompting Blakeslee to decide that the best way to continue flying was to join the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

Blakeslee was trained in Canada and then sent to England on May 15, 1941. There, he was assigned to Number 401 Squadron CAF, which was part of the Biggin Hill Wing. Pilot Officer Blakeslee first saw combat on November 18, 1941, flying sweeps, when he damaged a BF-109 near Le Touquet. He claimed his first kill on November 22, 1941, a BF-109 over Desvres, about 10 miles south of Marck. On the same mission he damaged another BF-109 while returning to base. His next kills were claimed on April 28, 1942, probably destroying two FW190s. Although not a particularly good shot, he was receptive to the principles of air fighting tactics and soon proved to be a leader, both in the air and on the ground.

By the summer of 1942, he an acting flight lieutenant and was awarded the British Distinguished Flying Cross on August 14, 1942. The presentation stated that “Acting Flight Lieutenant Donald Mathew BLAKESLEE (Can.J/4551), Royal Canadian Air Force. 133 (E) Squadron. This officer has completed a large number of sorties over enemy territory. He has destroyed one, destroyed, and damaged several more hostile aircraft. He is a fine whose keenness has proved most inspiring. He then completed his first tour of duty, clocking 200 combat hours with three victories.”

Blakeslee never wanted to join the American volunteer Eagle Squadrons, because he claimed that “they exaggerated their claims.” However, when informed he was to be assigned as an instructor pilot, he volunteered to be sent to Number 133 (Eagle) RAF as its commanding officer. It was the only way to maintain his combat status. During raid Dieppe, France on August 18, 1942, Blakeslee shot down additional FW-190 and probably destroyed another on the 19th, thus achieving his first ace status. Blakeslee would go on to achieve ace status twice more, but that was not the only claim to fame he would have to his name.

On September 12, 1942, the 71st, 121st, and 133rd Squadrons were activated as the USAAF’s 4 Group,  operating from a former RAF field at Debden. After a few months of flying Spitfires, the group was re-equipped with the new Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. On April 15, 1943, Blakeslee claimed an FW-190 for the group’s first P-47 kill and claimed another FW-190 on May 14, 1943, both near Knocke. Leading the 335th Squadron of the 4th Fighter Group, Blakeslee led the group into Germany the first time on July 28. Towards the end of the year, Blakeslee led the group more often and developed a tactic of circling above any air battle and so he could better direct his fighters.

operating from a former RAF field at Debden. After a few months of flying Spitfires, the group was re-equipped with the new Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. On April 15, 1943, Blakeslee claimed an FW-190 for the group’s first P-47 kill and claimed another FW-190 on May 14, 1943, both near Knocke. Leading the 335th Squadron of the 4th Fighter Group, Blakeslee led the group into Germany the first time on July 28. Towards the end of the year, Blakeslee led the group more often and developed a tactic of circling above any air battle and so he could better direct his fighters.

Blakes first flew the P-51 Mustang in December 1943 and subsequently worked diligently to have the 4th Fighter Group re-equipped with the new aircraft as soon as possible, especially after assuming command of the 4th Fighter Group on January 1, 1944. The 8th Air Force Command eventually granted the request, stipulating that the pilots must be on the P-51 within 24 hours of receiving them. Blakeslee agreed, instructing his pilots to “learn how to fly them on the way the target.”

Blakeslee piloted the first Mustang over Berlin on March 6, 1944, defending Boeing B-17s and Consolidated B24s. The 4th Fighter Group, under Blakeslee’s command, escorted the mass daylight raids of the 8th Air Force over Occupied Europe and became one of the highest-scoring groups of VIII Fighter Command. The 4th’s aggressive tactics under Blakeslee proved effective, and they surpassed the 500-kill mark by the end of April 1944. By the end of the war, the group had destroyed 1,020 German planes (550 in flight and 470 on the ground). The next landmark for Blakeslee was leading the first “shuttle” mission to Russia on June 21, 1944, flying 1,470 miles in a mission lasting over 7 hours.

In September of 1944, Don Blakeslee was finally grounded following the loss of several high-scoring USAAF aces. He had achieved 15 kills in the air two more on the ground. He had flown 500 operational sorties and accumulated 1,000 hours. Barrett Tillman, who served as an executive secretary the American Fighter Aces Association, stated that Blakeslee had more missions and hours “than any other American fighter pilot of World War II.” Blakeslee retired from the United States Force in 1965 with the rank of colonel. In his obituary in The Guardian, Blakeslee was described as “the most decorated Second World War US Air Force fighter pilot.” Blakeslee’s personal standing among Allied pilots was considerable. British ace Johnnie Johnson described him as “one of the best leaders ever to fight over Germany.”

Following the conclusion of World War II, Blakeslee continued his service in the newly established United States Air Force. During the Korean War, he commanded the 27th Fighter-Escort Group at Taegu Air Base in South Korea and Itazuke Air Base in Japan, flying several missions in the F-84 Thunderjet from December 1950 to  March 1951. In March 1963, he was promoted to colonel, and his final assignment was as Special Assistant to the Director of Operations for the Seventeenth Air Force, serving from 1964 until his retirement on April 30, 1965. After retiring, Blakeslee lived in Miami, Florida. He married Leola Fryer in 1944 and had one daughter. She passed away in 2005. Blakeslee died on September 3, 2008, at his home due to heart failure. On Friday September 18, 2008, Colonel Don Blakeslee and his wife’s ashes were interred at Arlington National Cemetery. The ceremony took place at 1100 hours and was open to the public. The 4th Fighter Wing also did a flyover at the ceremony.

March 1951. In March 1963, he was promoted to colonel, and his final assignment was as Special Assistant to the Director of Operations for the Seventeenth Air Force, serving from 1964 until his retirement on April 30, 1965. After retiring, Blakeslee lived in Miami, Florida. He married Leola Fryer in 1944 and had one daughter. She passed away in 2005. Blakeslee died on September 3, 2008, at his home due to heart failure. On Friday September 18, 2008, Colonel Don Blakeslee and his wife’s ashes were interred at Arlington National Cemetery. The ceremony took place at 1100 hours and was open to the public. The 4th Fighter Wing also did a flyover at the ceremony.

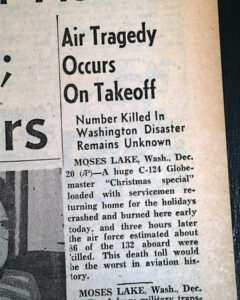

It was December 20, 1952, at the height of the Korean War. Operation Sleigh Ride…a United States Air Force airlift program to bring US servicemen who were fighting in the Korean War home for Christmas. I can imagine the excitement in the air. A chance to “take a break” from the ugliness of war even if only for a short time and spend Christmas at home. At around 6:30pm PST, the C-124 lifted off from Larson

It was December 20, 1952, at the height of the Korean War. Operation Sleigh Ride…a United States Air Force airlift program to bring US servicemen who were fighting in the Korean War home for Christmas. I can imagine the excitement in the air. A chance to “take a break” from the ugliness of war even if only for a short time and spend Christmas at home. At around 6:30pm PST, the C-124 lifted off from Larson  Air Force Base near Moses Lake, Washington. The plane was en route to Kelly Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas. Then the unthinkable happened. Just seconds after taking, the left wing struck the ground, and the airplane cartwheeled, broke up, exploded, killing 82 of the 105 passengers and 5 of the 10 crew members.

Air Force Base near Moses Lake, Washington. The plane was en route to Kelly Air Force Base, San Antonio, Texas. Then the unthinkable happened. Just seconds after taking, the left wing struck the ground, and the airplane cartwheeled, broke up, exploded, killing 82 of the 105 passengers and 5 of the 10 crew members.

Investigation into the accident revealed that the aircraft’s elevator and rudder gust locks had not been disengaged prior to departure. The reports I have read did not specifically say that the accident was due to pilot error, but I also could not find information stating that is could have been mechanical failure. From that, I have to assume that the crew forgot to disengage the elevator and rudder gust locks, and the plane simply lost control.

I can’t imagine the devastation of waiting at home for your soldier to come home for Christmas, only to hear that on their way home to you, they were in a crash that took their life. Of course, they wanted their soldier home for Christmas, but my guess is that many carried the weight of that desire for years. If their soldier had stayed in Korea, they might have later come home from the war alive. It was all just too much to bear. This would be the deadliest crash in history, until the Tachikawa air disaster, which also involved a Douglas C-124A-DL Globemaster II and claimed 129 lives. Of course, no crash that involves loss of life, is a minor thing. The devastation the families feel is beyond comprehension.

I can’t imagine the devastation of waiting at home for your soldier to come home for Christmas, only to hear that on their way home to you, they were in a crash that took their life. Of course, they wanted their soldier home for Christmas, but my guess is that many carried the weight of that desire for years. If their soldier had stayed in Korea, they might have later come home from the war alive. It was all just too much to bear. This would be the deadliest crash in history, until the Tachikawa air disaster, which also involved a Douglas C-124A-DL Globemaster II and claimed 129 lives. Of course, no crash that involves loss of life, is a minor thing. The devastation the families feel is beyond comprehension.

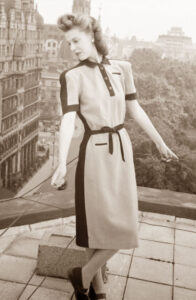

During World War II, as with other wars, things that were needed for the war effort had to be rationed. Things like metal, gasoline, even food made sense to me, but while I was listening to a book called “The Monuments Men” and shorter skirts were mentioned. My first thought was, “How did shorter skirts help the war effort? The men’s morale maybe, but seriously…how?” Well, it turns out that morale had nothing to do with it. The reasons lay elsewhere. Apparently, wool and silk were in high demand to make uniforms and parachutes. For manufacturers, that meant using materials like rayon and viscose (a semi-synthetic type of rayon fabric made from wood pulp that is used as a silk substitute. It has a similar drape and smooth feel to the luxury material) to make most civilians clothing.

During World War II, as with other wars, things that were needed for the war effort had to be rationed. Things like metal, gasoline, even food made sense to me, but while I was listening to a book called “The Monuments Men” and shorter skirts were mentioned. My first thought was, “How did shorter skirts help the war effort? The men’s morale maybe, but seriously…how?” Well, it turns out that morale had nothing to do with it. The reasons lay elsewhere. Apparently, wool and silk were in high demand to make uniforms and parachutes. For manufacturers, that meant using materials like rayon and viscose (a semi-synthetic type of rayon fabric made from wood pulp that is used as a silk substitute. It has a similar drape and smooth feel to the luxury material) to make most civilians clothing.

In addition to the types of material, the manufacturers had to find a way to actually conserve the amount of fabric being used, so to conserve fabric, dressmakers and manufacturers began designing shorter skirts and slimmer silhouettes. In the book, the comment was made that because so many people walked to work, the women had shapely legs, so I guess the men appreciated the new styles, much like when the miniskirt came into style in the 70s. Although, the women of the World War II era didn’t wear miniskirts. The dresses were just about knee length or slightly longer. The use of shoulder pads ended in World War II as well, although it has made periodic comebacks over the years. Another way that the manufacturers found to conserve fabric, was

the elimination of the cuff on men’s slacks. Oddly, that change was not as much appreciated by the men in World War II, although these days, cuffs on pants are a rarity, if you see them at all. Mostly these days, you might see pant legs rolled and that mostly on women, but not a real cuff.

the elimination of the cuff on men’s slacks. Oddly, that change was not as much appreciated by the men in World War II, although these days, cuffs on pants are a rarity, if you see them at all. Mostly these days, you might see pant legs rolled and that mostly on women, but not a real cuff.

Dress hemlines have been known to fluctuate with the times. The pre 1900s showed women with long full dresses that even dragged the ground, full slips and absolutely no ankles or feet showing. I suppose anyone showing an ankle or foot would be considered…loose. By the 1900s, the era of my Spencer great aunts, the skirts were still very long, but with a slimmer cut and fewer full slips to carry around. One of the oddest style came in 1910, when the Hobble Skirt came out. Of course, variations would be the pencil skirt. The roaring 20s, brought a carefree attitude and long cumbersome skirts were replaced with short, knee length (and maybe slightly shorter) skirts, suitable for rather wild dancing. With the stock market crash of 1929, the Crashing 30’s began, and skirts were again long and very conservative. There was no need for flashy dancewear, and there was not much dancing going on. Then, came World War II. Our men were fighting and we…the ones back at home had to make some sacrifices, So, came the shorter skirts made of rayon and such to save the normal materials for our “boys, fighting over there.” When the war ended, the ration weary women went back to their fuller, and slightly longer skirt, because…well they could. And then came the 60s…the era of free love and free expression. The miniskirt arrived, much to the horror of our parents. The Beatles were the rage, and the skirts grew (or shrank) to ever

shorter lengths. By the late 70s, the midi and maxiskirts had arrived. And so came the Hippie era. Everything was “free flowing and filled with flowers.” To me, it seems that since that time, skirts have been a mix of lengths, from the micromini to the maxi, but in reality, many women gave up skirts completely for jeans, short shorts (hot pants), capris, or whatever else suited our “fancies” because it was all available. I suppose a day could come again, when fashion would change because of war, politics, or personal preference. Styles often repeat. Time will tell that story.

shorter lengths. By the late 70s, the midi and maxiskirts had arrived. And so came the Hippie era. Everything was “free flowing and filled with flowers.” To me, it seems that since that time, skirts have been a mix of lengths, from the micromini to the maxi, but in reality, many women gave up skirts completely for jeans, short shorts (hot pants), capris, or whatever else suited our “fancies” because it was all available. I suppose a day could come again, when fashion would change because of war, politics, or personal preference. Styles often repeat. Time will tell that story.

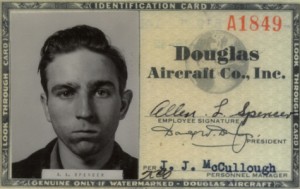

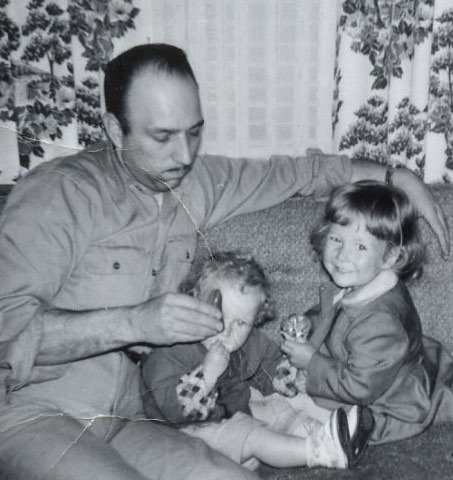

As a young man, my dad, Allen L Spencer worked for Douglas Aircraft Company. Of course, he wasn’t there when the DC-3 took its first flight, mostly because he was only eleven at the time, but I have a feeling that if he happened to see a plane flying overhead, he was probably enamored of them immediately. So, I’m sure that the idea of working to build these machines, much have been quite thrilling for him. I am also quite sure that Dad might have worked on the DC-3, since it was a plane used in World War II. Dad left Douglas Aircraft Company in early 1943, when he was called to serve in World War II. After basic training, he was called to be part of a B-17 Bomber crew. I’m sure they wanted to make use of his experience at Douglas Aircraft Company, because soon, Dad was the flight engineer and top turret gunner on his crew. The flight engineer needs to know everything about the plane, because let’s face it, in a plane, you can’t pull over if something goes wrong.

As a young man, my dad, Allen L Spencer worked for Douglas Aircraft Company. Of course, he wasn’t there when the DC-3 took its first flight, mostly because he was only eleven at the time, but I have a feeling that if he happened to see a plane flying overhead, he was probably enamored of them immediately. So, I’m sure that the idea of working to build these machines, much have been quite thrilling for him. I am also quite sure that Dad might have worked on the DC-3, since it was a plane used in World War II. Dad left Douglas Aircraft Company in early 1943, when he was called to serve in World War II. After basic training, he was called to be part of a B-17 Bomber crew. I’m sure they wanted to make use of his experience at Douglas Aircraft Company, because soon, Dad was the flight engineer and top turret gunner on his crew. The flight engineer needs to know everything about the plane, because let’s face it, in a plane, you can’t pull over if something goes wrong.

The Douglas DC-3 is “a propeller-driven airliner produced by the Douglas Aircraft Company. The DC-3 significantly impacted the airline industry from the 1930s through the 1940s and during World War II. It was developed as a larger, enhanced 14-bed sleeper version of the Douglas DC-2. This low-wing metal monoplane features traditional landing gear and is propelled by two radial piston engines with 1,000–1,200 horsepower. Initially, civil DC-3s were equipped with the Wright R-1820 Cyclone engine, but later models adopted the Pratt and Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp engine. The DC-3 boasts a cruising speed of 207 miles per hour, can accommodate 21 to 32 passengers or carry 6,000 pounds of cargo, has a range of 1,500 miles, and is capable of operating from short runways.”

The DC-3 was filled with exceptional qualities that earlier versions didn’t have. I think that is common as technology advances. It was fast, had a good range. It was more reliable than the prior versions, and it even provided greater passenger comfort. Clearly, it was not designed just for the war, but to go on into the future too. Prior to World War II, it pioneered many air travel routes. It could cross the continental United States from New York to Los Angeles in 18 hours with only three stops. Of course, these days that seems like nothing, but in those days, it was a big deal. It was one of the first airliners that could profitably carry passengers without relying on mail subsidies. In 1939, at the peak of its dominance in the airliner market, approximately 90% of airline flights worldwide were operated by a DC-3 or its variants.

Sadly, after the war, the airliner market was inundated with surplus transport aircraft, rendering the DC-3 less competitive due to its smaller size and slower speed compared to aircraft built during the war. With all that against it, the DC-3 became obsolete on main routes. Soon, it was replaced by more advanced types such as the Douglas DC-4 and Convair 240. However, the design of the DC-3 proved adaptable and remained useful on less commercially demanding routes.

Civilian DC-3 production ceased in 1943 with a total of 607 aircraft. Military variants, including the C-47

Skytrain (known as the Dakota in British RAF service). The Soviet-built and Japanese-built versions increased total production to over 16,000 planes. Many continued to serve in various niche roles. It was estimated that 2,000 DC-3s and military derivatives were still operational in 2013. By 2017, more than 300 were still flying, and as of 2023, approximately 150 are estimated to remain in service. This, it would seem, is a very versatile airplane.

Skytrain (known as the Dakota in British RAF service). The Soviet-built and Japanese-built versions increased total production to over 16,000 planes. Many continued to serve in various niche roles. It was estimated that 2,000 DC-3s and military derivatives were still operational in 2013. By 2017, more than 300 were still flying, and as of 2023, approximately 150 are estimated to remain in service. This, it would seem, is a very versatile airplane.

People tend to be drawn to mysteries, especially when it involves the disappearance of a celebrity. Of course, we always hope for a good outcome, but that is not always meant to be. Many people these days don’t know who Glenn Miller is, mostly because of the era he came from. Glenn Miller was an American big band conductor, arranger, composer, trombone player, and recording artist before and during World War II, but during World War II, he was an officer in the US Army Air Forces. It was in his role as a military officer when Glenn Miller went missing on December 15, 1944, after heading out over the English Channel on a small military plane bound for Paris. or apparently so.

People tend to be drawn to mysteries, especially when it involves the disappearance of a celebrity. Of course, we always hope for a good outcome, but that is not always meant to be. Many people these days don’t know who Glenn Miller is, mostly because of the era he came from. Glenn Miller was an American big band conductor, arranger, composer, trombone player, and recording artist before and during World War II, but during World War II, he was an officer in the US Army Air Forces. It was in his role as a military officer when Glenn Miller went missing on December 15, 1944, after heading out over the English Channel on a small military plane bound for Paris. or apparently so.

Shortly after the world learned that Miller, one of the University of Colorado Bould most distinguished alumni, had disappeared, the conspiracy theories began to fly. The fact that Miller was never found, just adds to the mystery surrounding this case. That doesn’t mean that the search is over. Still, 80 years is a long time for a mystery to remain unsolved. It is not for lack of trying, that the disappearance remains a mystery. For Miller’s family, I’m sure all the continuing speculation gets to be annoying, especially when it involves some sensationalistic theories designed to discredit Miller. Theories include things like an assassination before he even boarded the plane he was supposedly on for the purpose of a secret mission for Dwight Eisenhower, or that he made it to Paris ha died of a heart attack in a bordello (I find this one very distasteful, in that it is defamation of character), or that the small plane he was on was destroyed by bombs jettisoned from a phalanx of Allied bombers passing overhead on their way back from an aborted mission over Germany. I’m sure there were others, but without proof, people shouldn’t speculate.

Eventually, long after the war was over, the truth (at least as far as it will ever be proven) came out. Typical of the US government…and many other governments too, I’m sure…documents from the investigation were boxed  up after the war, sent to the United States and locked away. I understand the need to keep wartime documents under wraps, but so many years later…why is it necessary to hide that information from the grieving families. The information was there, they were just not given access. It turns out that witnesses saw Miller get on the plane, and the plane, a C64 Norseman, had a known problem with the carburetor heaters. While the bodies and the plane were not found, it is pretty certain that the freezing weather that day froze the lines, causing the plane to crash shortly after takeoff. I don’t suppose we will know for sure, until the plane is found, but after all these ears, that seems unlikely.

up after the war, sent to the United States and locked away. I understand the need to keep wartime documents under wraps, but so many years later…why is it necessary to hide that information from the grieving families. The information was there, they were just not given access. It turns out that witnesses saw Miller get on the plane, and the plane, a C64 Norseman, had a known problem with the carburetor heaters. While the bodies and the plane were not found, it is pretty certain that the freezing weather that day froze the lines, causing the plane to crash shortly after takeoff. I don’t suppose we will know for sure, until the plane is found, but after all these ears, that seems unlikely.

I’ve been listening to an audiobook called the “The Germans In Normandy.” Of course, I’m not a fan of the Germans in World War II, but this book talks about the German perspective about that battle. We all think that the German soldiers went blindly into battle, faithful to their leader…or at least most of them, but the German soldiers all had doubts. They all thought Hitler was about half crazy, but they were afraid to say anything…for the most part anyway.

I’ve been listening to an audiobook called the “The Germans In Normandy.” Of course, I’m not a fan of the Germans in World War II, but this book talks about the German perspective about that battle. We all think that the German soldiers went blindly into battle, faithful to their leader…or at least most of them, but the German soldiers all had doubts. They all thought Hitler was about half crazy, but they were afraid to say anything…for the most part anyway.

As I’ve listened to the book, the Hitler Youth came into the story, and I began to wonder, not only how the Hitler Youth felt about Hitler and the Third Reich, but how many of them stayed faithful to Hitler’s ideals and how many of them turned from Hitler’s ideals. So, I did a little research.

Hitler believed that by conditioning young people in groups as the Hitler Youth, they “never be free again, not in their whole lives.” While many young individuals were profoundly influenced by these organizations, support for the Hitler Youth was not as extensive as Nazi leaders had hoped. The youth initially joined and were very excited about their participation, but as time went on, their interest declined. Many young people skipped certain meetings and activities, despite mandatory attendance requirements, resulting in inconsistent loyalty. The reasons behind their declining enthusiasm for Hitler Youth activities were not solely political or moral at times, young individuals simply grew weary of the numerous obligations or became bored. In 1939, the Social Democratic Party, which had been banned by the Nazis and operated covertly, published a report on German  youth that highlighted some of this frustration. Young people are notorious for promoting change, and that was what they thought they were doing. The restrictions placed on them by the organizers of the Hitler Youth made many of the youth want to walk away.

youth that highlighted some of this frustration. Young people are notorious for promoting change, and that was what they thought they were doing. The restrictions placed on them by the organizers of the Hitler Youth made many of the youth want to walk away.

Of those who did walk away was Hans Scholl, along with Alexander Schmorell, one of the two founding members of the White Rose resistance movement in Nazi Germany. The White Rose was a non-violent, intellectual resistance group in the Third Reich. The group was led by Hans Scholl, and his sister, Sophie, along with several other former Hitler Youth members. The students attended the University of Munich. Their objective was to raise awareness through anonymous leaflets and a graffiti campaign that called for active opposition to the Nazi regime. the anonymity of their actions, Third Reich had spies everywhere. Hans became disillusioned because he had assembled a collection of folk songs, and his young charges loved to listen to him singing, accompanying himself on his guitar. He knew not only the songs of Hitler Youth but also the folk songs of many peoples and many lands. He loved how magically a Russian or Norwegian song sounded with its dark and dragging melancholy. And he thought about what it told of the soul of those people and their homeland! Then, Hans was told the songs were not allowed. He had aways thought that people should be able to pursue the things that interested them, but now the Hitler Youth program was no longer what he thought it was, and he walked away.

Hans and Sophie Scholl, along with Christoph Probst, were prominent members of the core group. The activities of The White Rose in Munich began on June 27, 1942, and ended in the arrest of the group by the Gestapo on February 18, 1943. Those apprehended now faced death sentences or imprisonment in show trials conducted

by the Nazi People’s Court (Volksgerichtshof). During the trial, Sophie interrupted the judge multiple times, but her remarks went unacknowledged. The defendants were not given the opportunity to speak. They had no means to defend themselves and were declared guilty during the “trial.” They were executed by guillotine four days after their arrest, on February 22, 1943. The group, which had only been active for eight months, had never committed any violent acts. They were sentenced to death. Hitler’s regime regarded them as a greater threat due to their pamphlets and art than if they had killed people.

by the Nazi People’s Court (Volksgerichtshof). During the trial, Sophie interrupted the judge multiple times, but her remarks went unacknowledged. The defendants were not given the opportunity to speak. They had no means to defend themselves and were declared guilty during the “trial.” They were executed by guillotine four days after their arrest, on February 22, 1943. The group, which had only been active for eight months, had never committed any violent acts. They were sentenced to death. Hitler’s regime regarded them as a greater threat due to their pamphlets and art than if they had killed people.

When you lose a parent, it seems like time stops; and for them, I guess it does…at least on the earth, but in reality…and for the rest of us, time marches on. Of course, that means that very quickly we find ourselves wondering how it could possibly be that…in my case, my dad, Allen Spencer has been in Heaven for 17 years. My dad was the first of my parents, and of my husband’s parents to move to Heaven, so for me, it was like going into the unknown. To make matters worse, I was somehow under the impression that my dad would be around for the rest of my life. Yes, I know how that sounds, but the mind thinks its own thoughts, we don’t plan the thoughts the pop into our heads.

When you lose a parent, it seems like time stops; and for them, I guess it does…at least on the earth, but in reality…and for the rest of us, time marches on. Of course, that means that very quickly we find ourselves wondering how it could possibly be that…in my case, my dad, Allen Spencer has been in Heaven for 17 years. My dad was the first of my parents, and of my husband’s parents to move to Heaven, so for me, it was like going into the unknown. To make matters worse, I was somehow under the impression that my dad would be around for the rest of my life. Yes, I know how that sounds, but the mind thinks its own thoughts, we don’t plan the thoughts the pop into our heads.

My sisters, Cheryl Masterson, Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, and Allyn Hadlock, were blessed with amazing parents. They raised us in a loving Christian home. We were blessed with parents who taught is how to become respectable members of society, and also loving members of a family. When Dad went to Heaven, he knew that we would take care of Mom…and we did. It was not just a sense of duty to them both, but of love and respect for them both. I think it is the hope of all of our family

members, now including grandchildren, great grandchildren, and great great grandchildren; that we have grown into people that would make our parents proud. They left us a legacy of love and caring, that we want to pass on to our own children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren.

members, now including grandchildren, great grandchildren, and great great grandchildren; that we have grown into people that would make our parents proud. They left us a legacy of love and caring, that we want to pass on to our own children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren.

Dad’s legacy included so much more. He had served in the Army Air Forces, in World War II, stationed at Great Ashfield, Suffolk, England with the 8th Air Force 385th Bomber Group. He served with honor and dignity, and we have always been proud his service. He was a valued member of his crew, serving as the top turret gunner and flight engineer, and he saved his plane and crew from crashing when he hung out of the open bomb bay doors to manually lower the stuck landing gear as the ground rushed toward them. He was a hardworking man, working two or more jobs, if necessary, to support his family. That taught us a strong work ethic and a strong sense of giving, that we continue to carry with us today.

While 17 years have passed since our dad went to Heaven, we still want to do everything we can to continue to make his proud of the daughters he and Mom raised. We are all prayer warriors, and we pray over an ever-growing list of prayer requests from family and friends, which I think would have made our parents the proudest of the children they raised. We miss our parents so much and thinking about them on this the 17th anniversary of my dad’s homegoing, still makes us sad, but we know that we will see them again, when we are all reunited in Heaven. We love and miss you dad and mom, and we can’t wait to see you again one day.