World War II

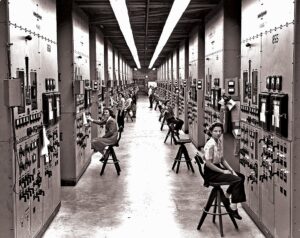

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

They were actually monitoring the manufacturing of enriched uranium that was to be used to make the “Little Boy” atomic bomb for the Hiroshima nuclear bombing to be carried out on August 6, 1945. The Manhattan Project, which was established to develop nuclear weapons, required uranium-235 (U235), the fissionable isotope of uranium. The vast majority of uranium that is mined from the ground is uranium-238. Only about while only 0.7% is U235. The scientists in charge of the project developed several processes for separating the isotopes of uranium, including electromagnetic separation and gaseous diffusion.

“The Y-12 factory was built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to house 1,152 calutrons, a machine used for isotope separation. The word “calutron” is a portmanteau of California University Cyclotron. Calutrons, a variation on mass spectrometers, work by combining uranium with chlorine to make uranium tetrachloride, which is then ionized and put in a vacuum chamber with a magnetic field. When the charged particles move through the magnetic field, they move in a curve, the radius of which is proportional to the mass of the particles. The two isotopes differ in mass by about 1% and can thus be separated.”

The process of separating the U235 Uranium out of the oar was relatively simple, but it still required people to constantly monitor the calutrons. Unfortunately, during World War II, many of the men were fighting. That left a shortage of labor. There simply weren’t enough scientists to operate all of the calutrons. So, the government recruited farm girls to operate the calutrons instead. The main reason for using the young women, was that they were readily available, accustomed to hard work. A stipulation of their employment was that they were not to ask excessive questions, and they had to be loyal and docile. I’m sure these women thought they were doing something top secret and all, but I don’t think they had any idea of the gravity of this project. Lives were on the line, and lives would be lost. Still, they didn’t know that, so I suppose their superiors assumed it would let them sleep at night. I suppose it did. These women honestly didn’t know what they were a part of…some until years later. They would never forget what they did, and they would always wonder if it was right or wrong.

The Tennessee Eastman Company, which ran the Y-12 site, recruited around 10,000 local women between 1943 and 1945. They hired train operators with only a high school education, and they used a large local advertising campaign to recruit workers. One ad read, “When you’re a grandmother you’ll brag about working at Tennessee Eastman.” Word of mouth brought in several other workers. Of course, in hard times, a big motivator was the money being paid. Plus, these women were patriots, and this work was for the war effort. They were trained for three weeks, and they went to work.

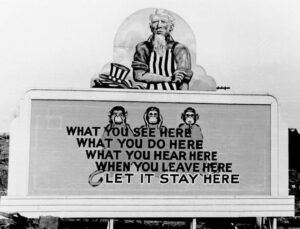

The Tennessee Eastman Company was loyal to the cause. They put a billboard on the premises reading “What you see here / what you do here / what you hear here / when you leave here / let it stay here,” with three wise monkeys to demonstrate “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” Another billboard at the Oak Ridge location,  encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

The work these women did was not what would be considered labor intensive by any means. The women sat on high stools for 8-hour shifts, seven days per week, “monitoring gauges and adjusting knobs to keep the needles where they were supposed to be and recording readings.” The knobs the women were adjusting were simply labeled with cryptic letters. The women did not know what the letters stood for. What they were taught was that “if you got your M voltage up and your G voltage up, then Product would hit the birdcage in the E box at the top of the unit and if that happened, you’d get the Q and R you wanted.” Okay…whatever that meant. All they knew was that they had to make sure the machine remained at the correct temperature. That was vital and if it got too hot, they used liquid nitrogen to cool it down. If the needles reached a point where they could not control them, they had to call someone else to come help…immediately!!!

Former Calutron Girl Wynona Arrington Butner said, “We all wore little fountain-pen-sized dosimeters. Part of signing out of the plant was to check the amount of radiation that you had absorbed every day.” Civilian workers paid $2.50 per month (single) or $5.00 per month (family) for medical insurance. I don’t know if they understood what radiation could do to them or not, but if they did, they would know that the wages paid and even the insurance help, was probably not enough.

Some Calutron Girls had more of a sense of what they were working on than others. Butner, who had some training in chemistry, said she and others with a similar background had some sense of what they were doing. They knew they were producing “the Product,” and they guessed it was somewhere near the bottom of the periodic table. Willie Baker, on the other hand, said, “Even when somebody let it slip that we were building a bomb, I didn’t know what they meant. I was just a country girl. I had no understanding of what an atomic bomb was.” Later, I’m sure the gravity of the work she did, weighed heavily on Baker.

Over two years, the calutrons at Y-12 had produced about 140 pounds of U235. This was enough to make the first atomic bomb. By December 1945, enough uranium for a second Little Boy was available. Then, it all hit these women, because on August 6, 1945, when the US dropped the first bomb, “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima, Japan, the Calutron Girls were finally told what they had been working on. I can’t imagine how they must have felt. When they heard the news, some women were working, while others were in their dorm rooms. Someone came and told them that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan, and everyone there had played a part in making it. Yes, it was the enemy, and death happens in war. Nevertheless, the Calutron Girls had mixed feelings about their part in the bomb. Ruth Huddleston said she was “really happy at the time, because her boyfriend was stationed in Germany, and this would bring him back.” Still, it bothered her that she had a part in killing so many people, but she accepted that “if the bomb hadn’t been dropped, then probably more people would have been killed. …But even today, if I think too much about it, it bothers me.” Butner had a similar experience, because at the time, she was happy that the war was over and people she knew in the service could come  home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

Most of the Calutron Girls are gone now, but those who remain, such as Huddleston, regularly shared their stories with the public, often alongside Oak Ridge historian Ray Smith. The women are the subject of the nonfiction book “The Girls of Atomic City” by Denise Kiernan and the novel “The Atomic City Girls” by Janet Beard. I’m sure that many of these women suffered nightmares over the work they did, but did not know they were doing. While I know they suffered much anxiety over that, I hope they also know that we are so grateful for their service to this great nation.

My nephew, Chris Killinger joined our family when he married my niece, Lacey (Stevens) Killinger a little under a year ago. Chris and Lacey are such a beautiful couple, and their wedding was just lovely. Since then, they have just been enjoying married life, and spending time with the kids, Brooklyn and Jaxon, who also joined our family with Chris married Lacey. They have all been a wonderful addition to our family.

My nephew, Chris Killinger joined our family when he married my niece, Lacey (Stevens) Killinger a little under a year ago. Chris and Lacey are such a beautiful couple, and their wedding was just lovely. Since then, they have just been enjoying married life, and spending time with the kids, Brooklyn and Jaxon, who also joined our family with Chris married Lacey. They have all been a wonderful addition to our family.

Chris and Lacey didn’t take a honeymoon right away, but later went to Mexico, and they had a super fun time. Chris and Lacey both have very demanding jobs, and they were ready for some down time. One of the highlights of the trip was when they went swimming in caves down there. The cave walls were beautiful, and it was a very different experience for them. The trip was one they won’t forget.

Chris is the office and purchasing manager for Atlas Aero Service, which is located at the Casper-Natrona  County International Airport. Chris’ job allows him to see all the planes that come and go from the airport. There is a huge variety of planes…military planes, cargo planes, commercial liners, and private jets (often with celebrities). Recently, however, the celebrity wasn’t the person on the plane…it was the plane. Chris knows planes, and he likes planes. He has a real interest in military planes. The plane that they got to work on recently was a plane that had been used in the movie “Tora, Tora, Tora” back in the 1970s. The movie was about the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, and while I know that Chris though it was very cool to work on that plane, I can’t help but think about how interested my dad, Al Spencer, Lacey’s grandpa would have loved to see that plane. He was the flight engineer and top turret gunner on a B-17 during World War II, so that plane would have been so cool for him to see. I’m glad Chris got that chance…such a cool experience, and one he will never forget for sure.

County International Airport. Chris’ job allows him to see all the planes that come and go from the airport. There is a huge variety of planes…military planes, cargo planes, commercial liners, and private jets (often with celebrities). Recently, however, the celebrity wasn’t the person on the plane…it was the plane. Chris knows planes, and he likes planes. He has a real interest in military planes. The plane that they got to work on recently was a plane that had been used in the movie “Tora, Tora, Tora” back in the 1970s. The movie was about the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, and while I know that Chris though it was very cool to work on that plane, I can’t help but think about how interested my dad, Al Spencer, Lacey’s grandpa would have loved to see that plane. He was the flight engineer and top turret gunner on a B-17 during World War II, so that plane would have been so cool for him to see. I’m glad Chris got that chance…such a cool experience, and one he will never forget for sure.

Recently, Chris and Lacey bought a new camper, and they have been having a great time with it. Chris has had

to learn how to pull it, which isn’t easy, but he is getting the hang of it. They have been having a great time going camping and they love their new camper. Lacey’s family takes yearly trips to Pathfinder Reservoir for a whole family week of fun, swimming, games, and lounging. Having a nice camper with room for their whole family is very important. The camper will get lots of use. Today is Chris’ birthday. Happy birthday Chris!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

to learn how to pull it, which isn’t easy, but he is getting the hang of it. They have been having a great time going camping and they love their new camper. Lacey’s family takes yearly trips to Pathfinder Reservoir for a whole family week of fun, swimming, games, and lounging. Having a nice camper with room for their whole family is very important. The camper will get lots of use. Today is Chris’ birthday. Happy birthday Chris!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

In June of 1942, Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping, a 24-year-old British pilot, who was part of the 260 Squadron of the RAF Volunteer Reserves was tasked with flying P-40 Kittyhawk (serial code ET574), on a ferry flight to a neighboring British airbase to have the undercarriage repaired. The upcoming Summer Offensive that year, was to include the P-40s. Copping took off on June 28 and headed West. He was never seen again, even with extensive searches being undertaken. Both the aircraft and its pilot were reported missing. After a time, the search was called off, because they couldn’t find anything.

In June of 1942, Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping, a 24-year-old British pilot, who was part of the 260 Squadron of the RAF Volunteer Reserves was tasked with flying P-40 Kittyhawk (serial code ET574), on a ferry flight to a neighboring British airbase to have the undercarriage repaired. The upcoming Summer Offensive that year, was to include the P-40s. Copping took off on June 28 and headed West. He was never seen again, even with extensive searches being undertaken. Both the aircraft and its pilot were reported missing. After a time, the search was called off, because they couldn’t find anything.

The lost flight stayed a mystery for almost 70 years. Then, in April 2012, workers of a Polish Oil company discovered the remarkably well-preserved remains of a P-40. It’s quite likely that they not only had no idea how it could have come to be there, nor when. Nevertheless, the desert’s extremely dry conditions had basically ‘mummified” the P-40, as it only showed minimal rust and decay.

The wings of the P-40 were half-buried under the sand, but they were still in very good condition, with the exception of the fact that the fabric-covered control surfaces had rotten away. Even the cockpit was still somewhat preserved, and the aircraft still had live ammunition loaded in the magazines of its six machine guns.

When the authorities were called in, they were easily able to link the downed P-40 Kittyhawk to Dennis  Copping, because of its relatively good condition. They finally knew what had happened to Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping and his Kittyhawk exactly 69 years, 9 months, and 14 days later. The only thing missing was the pilot. It was then assumed that Copping had survived the crash, but where was he? The only thing they could assume was that he must have tried to walk out. The problem is that Copping was lost and alone in the middle of the largest desert on Earth. They began the search again, but this time with the plane as a starting point.

Copping, because of its relatively good condition. They finally knew what had happened to Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping and his Kittyhawk exactly 69 years, 9 months, and 14 days later. The only thing missing was the pilot. It was then assumed that Copping had survived the crash, but where was he? The only thing they could assume was that he must have tried to walk out. The problem is that Copping was lost and alone in the middle of the largest desert on Earth. They began the search again, but this time with the plane as a starting point.

They found a small makeshift camp built next to the aircraft. Near it was the plane’s battery and radio. This meant that Copping probably attempted to broadcast for help. Unfortunately, the radio, or at least the internal workings of it had been destroyed by the crash landing. Finally, unable to call for help, Copping knew he would have to leave the plane and go for help. The teams continued their search, and a group of Italian historians uncovered a number of human bones five kilometers from the crash site. However, it was decided that those bones probably “did not belong” to Copping as they were “too old” to be his. Interestingly, the bones were never tested for any DNA. The historians were also able to find a section of the parachute, a keyfob, and a buckle stamped ‘1939,’ which were things Copping might have had with him at the time of his death.

Because of the desert’s dry conditions, the ET574 Kittyhawk was able to be fully restored. Of course, given the

years and the fact that it was a crash, the restoration is far from perfect. and it sports a historically inaccurate camouflage scheme. Maybe someday, it will be restored to a historically accurate condition. Nevertheless, it is the last surviving example of a Desert Air Force P-40 Kittyhawk in existence. The mystery was finally solved.

years and the fact that it was a crash, the restoration is far from perfect. and it sports a historically inaccurate camouflage scheme. Maybe someday, it will be restored to a historically accurate condition. Nevertheless, it is the last surviving example of a Desert Air Force P-40 Kittyhawk in existence. The mystery was finally solved.

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust. Because of the horrific things the man known as “Heydrich the Hangman” had done, the Czechoslovakian government-in-exile had decided they needed to get rid of him. The assassination didn’t go quite as planned when the assassin’s gun jammed, but a bomb thrown succeeded, albeit after a few days, caused Heydrich to contract sepsis, which ultimately lead to his death on June 4, 1942.

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust. Because of the horrific things the man known as “Heydrich the Hangman” had done, the Czechoslovakian government-in-exile had decided they needed to get rid of him. The assassination didn’t go quite as planned when the assassin’s gun jammed, but a bomb thrown succeeded, albeit after a few days, caused Heydrich to contract sepsis, which ultimately lead to his death on June 4, 1942.

There was no evidence that the people of the village of Lidice, Czechoslovakia had anything to do with his death, but that didn’t matter to Hitler. On June 10, 1942, Hitler sent his troops to obliterate the village of Lidice, Czechoslovakia. They had apparently been chosen as the example to all others that killing Hitler’s men was not going to be tolerated. The troops went in and killed all the adult males and deported most of the surviving women and children to concentration camps. The retaliation against these innocent people for something they had no control over, was brutal!! The massacre was carried out just a day after the Nazis rounded up the residents of Lidice, which is located near Prague. During the raid, SS troops herded all the town’s male residents aged 16 years and older…a total of more than 170…to a local farm and gunned them all down. The Germans then shot seven women who tried to run, and deported the remaining women to Ravensbrück concentration camp, which was a women’s slave labor camp. At Ravensbrück about 50 prisoners died, and three were recorded as “disappeared.” Of some 105 children in the village, one was reported shot while trying to run away, and approximately 80 were reported murdered in Chelmno Killing Center, and a handful were reported murdered in German Lebensborn orphanages. A few of the orphans, who were deemed “racially pure” by Nazi standards, were dispersed throughout German territory to be renamed and raised as Germans. After the massacre, SS agents burned Lidice, blew up what was left with dynamite, and leveled the debris. The destruction was to be complete at all costs.

On child, Marie Supikova, a Lidice survivor, was just 9 during the massacre. She tells of the horrible train ride to Poland after her father was executed and her mother was sent to Ravensbrück. “We cried and cried because we were very scared, upset and confused,” Supikova told BBC in a 2012 interview. Because she looked “racially

pure” she was spared. She was sent to a German family living in Poland and had her name changed to Ingeborg Schiller. “We all had blonde hair and blue eyes. We looked like the type that they could German-ize easily and raise as a good German girl or boy,” she said. Today, the Lidice Memorial honors the memory of the victims killed in the totally senseless annihilation of the village of Lidice.

pure” she was spared. She was sent to a German family living in Poland and had her name changed to Ingeborg Schiller. “We all had blonde hair and blue eyes. We looked like the type that they could German-ize easily and raise as a good German girl or boy,” she said. Today, the Lidice Memorial honors the memory of the victims killed in the totally senseless annihilation of the village of Lidice.

Not every soldier that stormed the beaches at Normandy, France on D-Day (June 6, 1944), carried a gun…or any other weapon. I’m not saying these men were more brave that their armed counterparts, because all of those men were targets. They all knew, going in that it was very unlikely that they would come home again. They were running onto an armed beach in broad daylight, with the plan of taking down the strongholds that existed there. The main difference between the armed soldiers and the medics was the inability to protect themselves. The medics weren’t there to fight. They were there to save. The were the only thing standing between the armed soldiers and certain death. Just the thought of that brings tears to my eyes. All the men who stormed those beaches faced almost certain death, and yet they knew they had to go. They couldn’t live with themselves if they didn’t do their best, be it killing the enemy soldiers or saving the wounded soldiers.

Not every soldier that stormed the beaches at Normandy, France on D-Day (June 6, 1944), carried a gun…or any other weapon. I’m not saying these men were more brave that their armed counterparts, because all of those men were targets. They all knew, going in that it was very unlikely that they would come home again. They were running onto an armed beach in broad daylight, with the plan of taking down the strongholds that existed there. The main difference between the armed soldiers and the medics was the inability to protect themselves. The medics weren’t there to fight. They were there to save. The were the only thing standing between the armed soldiers and certain death. Just the thought of that brings tears to my eyes. All the men who stormed those beaches faced almost certain death, and yet they knew they had to go. They couldn’t live with themselves if they didn’t do their best, be it killing the enemy soldiers or saving the wounded soldiers.

Most soldiers are trained to shoot, fight, and kill the enemy, but a combat medic is very different. He is trained to do the exact opposite. The medics had no guns. They went in to “battle” unarmed, and their mission wasn’t to attack the enemy, it was to dodge the bullets that were flying everywhere and get to the soldiers who had been wounded. Then they tried to get them off the battlefield so they could treat their wounds, and hopefully save their lives. Sometimes, they had to treat them where they were. Bullets don’t distinguish between a soldier and a medic.

There are, of course, far too many medics who have bravely gone in to try to save other soldiers at the risk of losing their own lives. While the armed soldiers fight the battles, medics pick up the pieces during and after the battle. It’s the medics who gather up the belongings of those they cannot save, so they can be returned to the families. They don’t really have much time before they must move on to the next wounded soldier, and so often they grab the dog tags, because it is the only true way to know who this soldier was. It’s the only way to let their family know that their brave soldier gave the ultimate sacrifice in battle.

My dad, Staff Sergeant Allen Spencer was a top turret gunner and flight engineer in one of the B-17s that

provided cover for the men as they stormed the beaches of Normandy that fateful day. My uncle, Jim Wolfe was one of the men below, storming the beaches. I don’t know if they knew each other then, but they would later, when my Uncle Jim married my dad’s sister, Ruth. It’s very hard to think about this battle, because so many lives were lost. I don’t know how anyone made it onto that beach without getting pelted with a barrage of bullets, but I am thankful for the medics who were there to try to pick up the pieces. Today marks the 80th anniversary of D-Day. From a grateful nation, we honor all who fought in that horrific battle. Very brave men all!!

provided cover for the men as they stormed the beaches of Normandy that fateful day. My uncle, Jim Wolfe was one of the men below, storming the beaches. I don’t know if they knew each other then, but they would later, when my Uncle Jim married my dad’s sister, Ruth. It’s very hard to think about this battle, because so many lives were lost. I don’t know how anyone made it onto that beach without getting pelted with a barrage of bullets, but I am thankful for the medics who were there to try to pick up the pieces. Today marks the 80th anniversary of D-Day. From a grateful nation, we honor all who fought in that horrific battle. Very brave men all!!

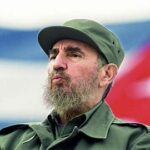

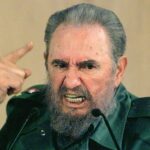

Fidel Castro was a thorn in the side of the United States and many other countries for many years. The CIA has long been rumored to have planned a series of assassination attempts against Castro using elaborate means, from using exploding cigars to poisoned pills to putting thallium salt in his shoes. Castro’s inner circle estimate that there were some 634 attempts to take his life including, giving Castro poisoned cigars, gifting him with a scuba suit lined with a skin-eating fungus, and stabbing him with a poisoned needle hidden inside a pen. There were also a number of plots to humiliate him as well, including the plot to spray Castro’s broadcasting studio with an LSD-like substance so he’d trip and fall while giving one of his

Fidel Castro was a thorn in the side of the United States and many other countries for many years. The CIA has long been rumored to have planned a series of assassination attempts against Castro using elaborate means, from using exploding cigars to poisoned pills to putting thallium salt in his shoes. Castro’s inner circle estimate that there were some 634 attempts to take his life including, giving Castro poisoned cigars, gifting him with a scuba suit lined with a skin-eating fungus, and stabbing him with a poisoned needle hidden inside a pen. There were also a number of plots to humiliate him as well, including the plot to spray Castro’s broadcasting studio with an LSD-like substance so he’d trip and fall while giving one of his  speeches and (hopefully) sound very silly too. And they wanted to dust his shoes with a substance that would make his beard fall out. Those didn’t happen either.

speeches and (hopefully) sound very silly too. And they wanted to dust his shoes with a substance that would make his beard fall out. Those didn’t happen either.

But the document officially reveals some of the schemes focused on Castro’s love of skin diving, hoping that he would pick up the beach shell and trigger an explosive, and another that considered giving the revolutionary a contaminated diving suit. That of course leaves a lot to chance and makes the beach unsafe for anyone else there, or that the wrong person might pick up the seashell. These ideas for assassination attempts, whether real or rumored, were wild and often crazy, but at the very least, they show just how frustrating a man Fidel Castro was. When people  consider booby trapping a seashell, you know they are grasping at straws. Still, such an attempt wouldn’t work on just any “mark” because not every mark would possibly pick up a seashell.

consider booby trapping a seashell, you know they are grasping at straws. Still, such an attempt wouldn’t work on just any “mark” because not every mark would possibly pick up a seashell.

In each of these attempts or imaginary attempts, Fidel Castro walked away unscathed. It wasn’t that attempts weren’t made it was just that Fidel Castro wasn’t killed in the attempts. I don’t know how he escaped, and many people wish he had not. His reign of terror was far too long and far too horrific. In the end, Castro, who overthrew US-backed Cuban leader Fulgencio Batista in 1959, died of natural causes on November 25, 2016, at age 90, leaving power to his brother Raul.

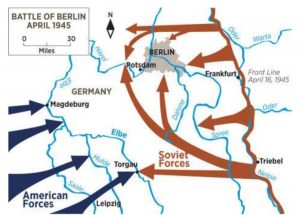

Sometimes, an event that potentially changed history, ends up getting little or no recognition. Thankfully, the picture that marked the event was taken, or the entire event might never have been noticed in history at all. This particular day is actually a very important day in the history of World War II, and therefore, the world. Elbe Day, which took place on April 25, 1945, is the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, near Torgau in Germany. This event marked an important step toward the end of World War II in Europe. If you have ever heard the saying, divide and conquer, you will know basically what happened on Elbe Day. A secret mission had been planned, and April 25, 1945, was the day it was carried out.

Sometimes, an event that potentially changed history, ends up getting little or no recognition. Thankfully, the picture that marked the event was taken, or the entire event might never have been noticed in history at all. This particular day is actually a very important day in the history of World War II, and therefore, the world. Elbe Day, which took place on April 25, 1945, is the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, near Torgau in Germany. This event marked an important step toward the end of World War II in Europe. If you have ever heard the saying, divide and conquer, you will know basically what happened on Elbe Day. A secret mission had been planned, and April 25, 1945, was the day it was carried out.

The plan was to have the Soviet army advance from the East, and the US Army advance from the West. The first contact between American and Soviet patrols occurred near Strehla exactly as planned, after First Lieutenant Albert Kotzebue, an American soldier, crossed the Elbe River in a boat with three men of an intelligence and reconnaissance platoon. Once they crossed to the east bank of the river, they met up with  forward elements of a Soviet Guards rifle regiment of the First Ukrainian Front, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Gardiev. Later that day, another patrol under Second Lieutenant William Robertson with Frank Huff, James McDonnell and Paul Staub met a Soviet patrol commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Silvashko on the destroyed Elbe bridge of Torgau. When the two armies connected at the Elbe River, the cutting of Germany in half is accomplished. In doing so, the strength of the German army was severely weakened. The German army was split in two, just like the country was, and in the end, that split made it impossible for the Germans to really fight the war they were engaged in. It was the beginning of the end for them.

forward elements of a Soviet Guards rifle regiment of the First Ukrainian Front, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Gardiev. Later that day, another patrol under Second Lieutenant William Robertson with Frank Huff, James McDonnell and Paul Staub met a Soviet patrol commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Silvashko on the destroyed Elbe bridge of Torgau. When the two armies connected at the Elbe River, the cutting of Germany in half is accomplished. In doing so, the strength of the German army was severely weakened. The German army was split in two, just like the country was, and in the end, that split made it impossible for the Germans to really fight the war they were engaged in. It was the beginning of the end for them.

Finally, on April 26, the commanders of the 69th Infantry Division of the First Army (United States) and the 58th Guards Rifle Division of the 5th Guards Army (Soviet Union) met at Torgau, southwest of Berlin. They knew that this moment was monumental, and it had to be documented. Arrangements were made for the  formal “Handshake of Torgau” photo to be taken of Robertson and Silvashko the following day, April 27. The Soviet, American, and British governments released simultaneous statements that evening in London, Moscow, and Washington, “reaffirming the determination of the three Allied powers to complete the destruction of the Third Reich.” They knew they must have victory at all costs.

formal “Handshake of Torgau” photo to be taken of Robertson and Silvashko the following day, April 27. The Soviet, American, and British governments released simultaneous statements that evening in London, Moscow, and Washington, “reaffirming the determination of the three Allied powers to complete the destruction of the Third Reich.” They knew they must have victory at all costs.

The fact that Elbe Day has never been an official holiday in any country, has not stopped people from looking to the day as something very special, and in the years after 1945 the memory of this friendly encounter gained new significance in the context of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Charles Askins, Jr was an American lawman, US Army officer, and writer. He served in law enforcement, mostly with the US Forest Service and Border Patrol, in the American Southwest prior to the Second World War. He was also known as Colonel Charles “Boots” Askins. He was the son of Major Charles “Bobo” Askins, a sportswriter and Army officer who served in the Spanish American War and World War I, and he was quickly following in his father’s footsteps.

Charles Askins, Jr was an American lawman, US Army officer, and writer. He served in law enforcement, mostly with the US Forest Service and Border Patrol, in the American Southwest prior to the Second World War. He was also known as Colonel Charles “Boots” Askins. He was the son of Major Charles “Bobo” Askins, a sportswriter and Army officer who served in the Spanish American War and World War I, and he was quickly following in his father’s footsteps.

Askins was born in Nebraska on October 28, 1987. The family moved to Oklahoma, where “Boots” Askins was raised. He had several careers in his life, but the first job was fighting forest fires in Montana. Then in 1927, the US Forest Service transferred him to New Mexico to be a Park Ranger at the Kit Carson National Forest. Askins fought fires in New Mexico, until 1930, when he was recruited by the US Border Patrol. Askins wrote in his memoir Unrepentant Sinner, that he had been involved in at least one gunfight every week. I’m sure that work on the US border brought with it a common risk of gunfights. Askins showed great skill, and during his service in the Border Patrol, he won many pistol championships. He was promoted to leader of the Border Patrol’s handgun skills program.

When the United States entered World War II, Askins served in the US Army as a battlefield recovery officer.  His work took him to North Africa, Italy, and he was in France on D-day. After being discharged from the Army following World War II, he spent several years in Spain as an attaché to the American embassy, helping Franco rebuild Spain’s munition plants. When he completed his assignment in Spain, he was reassigned to Vietnam, where he trained South Vietnamese soldiers in shooting and airborne operations. Askins had an exemplary career in the Army and while he was in the military, he indulged in big game hunting at every opportunity. He continued hunting after his retirement. In his lifetime, he held several big game hunting records, as well as two national pistol championships, an American Handgunner of the Year award, and innumerable smaller titles in competitive shooting. Askins spent his final years in the military at Fort Sam Houston, and he retired to San Antonio, Texas.

His work took him to North Africa, Italy, and he was in France on D-day. After being discharged from the Army following World War II, he spent several years in Spain as an attaché to the American embassy, helping Franco rebuild Spain’s munition plants. When he completed his assignment in Spain, he was reassigned to Vietnam, where he trained South Vietnamese soldiers in shooting and airborne operations. Askins had an exemplary career in the Army and while he was in the military, he indulged in big game hunting at every opportunity. He continued hunting after his retirement. In his lifetime, he held several big game hunting records, as well as two national pistol championships, an American Handgunner of the Year award, and innumerable smaller titles in competitive shooting. Askins spent his final years in the military at Fort Sam Houston, and he retired to San Antonio, Texas.

Askins inherited his writing skills from his father, “Bobo” Askins. “Boots” Askins was a creative writer, with a  number of books and over 1,000 magazine articles on subjects related to hunting and shooting. His writing career spanned 70 years, from 1929 until his death in March of 1999. While he was an excellent, his writings were considered controversial, mostly because he liked to graphically describe the numerous fatal shootings in his law enforcement and military careers, stating he had killed “27, not counting blacks and Mexicans.” He even once described himself as possibly a “psychopathic killer, and that he hunted animals so avidly because he was not allowed to hunt men anymore.” I suppose his killings were “justified” but maybe not really ethical. Still, many of them were necessary. He died on March 2, 1999, at the age of 91.

number of books and over 1,000 magazine articles on subjects related to hunting and shooting. His writing career spanned 70 years, from 1929 until his death in March of 1999. While he was an excellent, his writings were considered controversial, mostly because he liked to graphically describe the numerous fatal shootings in his law enforcement and military careers, stating he had killed “27, not counting blacks and Mexicans.” He even once described himself as possibly a “psychopathic killer, and that he hunted animals so avidly because he was not allowed to hunt men anymore.” I suppose his killings were “justified” but maybe not really ethical. Still, many of them were necessary. He died on March 2, 1999, at the age of 91.

During World War II, Hitler was terrorizing people, especially the Jews, Gypsies, and even Blacks. Hitler wanted to create an Aryan race dominate society, and truly preferred that anyone who did not fit that “mold” be removed from the Earth. The Aryan race consisted of tall, blonde-haired blue-eyed people, which is odd, considering the fact that Hitler was short (5’9″), and had brown hair. He did have blue eyes, but that was about the only part of him that fit the “mold” of the Aryan race. Nevertheless, he terrorized many people and for that reason, many people tried to escape the occupied areas of Europe, like France to the free areas like Spain.

During World War II, Hitler was terrorizing people, especially the Jews, Gypsies, and even Blacks. Hitler wanted to create an Aryan race dominate society, and truly preferred that anyone who did not fit that “mold” be removed from the Earth. The Aryan race consisted of tall, blonde-haired blue-eyed people, which is odd, considering the fact that Hitler was short (5’9″), and had brown hair. He did have blue eyes, but that was about the only part of him that fit the “mold” of the Aryan race. Nevertheless, he terrorized many people and for that reason, many people tried to escape the occupied areas of Europe, like France to the free areas like Spain.

One of the routes was to go across the ridge of the Pyrenees Mountain range, in order to cross the border into  the “promised land,” the neutral territory of Spain, to find a way of escape, a second chance, a future. It was a perilous route to go through the Pyrenees mountains, but it provided a means for hundreds of thousands of resistance fighters, civilians, Jews, allied soldiers and escaped prisoners of war to evade Nazi pursuers. Failure was not an option, because behind them was Nazi-occupied France, bringing certain imprisonment or death. Many of the travelers had come quite a distance, helped by resistance fighters and citizens who disagreed with all that was going on with the Nazi regime. The perilous journey up through rocky boulder fields and frozen glaciers was the final stretch in a long and dangerous trek across wartime Europe, hiding from German military, Gestapo secret police and SS paramilitary forces.

the “promised land,” the neutral territory of Spain, to find a way of escape, a second chance, a future. It was a perilous route to go through the Pyrenees mountains, but it provided a means for hundreds of thousands of resistance fighters, civilians, Jews, allied soldiers and escaped prisoners of war to evade Nazi pursuers. Failure was not an option, because behind them was Nazi-occupied France, bringing certain imprisonment or death. Many of the travelers had come quite a distance, helped by resistance fighters and citizens who disagreed with all that was going on with the Nazi regime. The perilous journey up through rocky boulder fields and frozen glaciers was the final stretch in a long and dangerous trek across wartime Europe, hiding from German military, Gestapo secret police and SS paramilitary forces.

The Freedom Trail, whose final ascent has a zig-zag path through an ice sheet, is an annual “walking memorial”

these days. People, some of them descendants of the original people who walked the trail in a desperate run for their lives, walk to remember those who went before them to freedom, those who could not make the journey and lost their lives, and those who lost their lives on the trail itself. The area really is quite beautiful, but I’m sure it didn’t feel that way to those who were running for their lives.

these days. People, some of them descendants of the original people who walked the trail in a desperate run for their lives, walk to remember those who went before them to freedom, those who could not make the journey and lost their lives, and those who lost their lives on the trail itself. The area really is quite beautiful, but I’m sure it didn’t feel that way to those who were running for their lives.

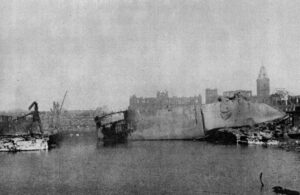

When a ship explodes in a port, the first assumption is that terrorists attacked, but that is not always the case. On April 14, 1944, cargo ship Fort Stikine exploded in a berth in the docks of Bombay, India, which is now known as Mumbai. The catastrophic explosion killed 1,300 people and injured another 3,000. It’s possible that the reason it was considered terrorists, or in this case, Japanese sabotage, was because the incident happened during World War II. Nevertheless, the explosion was actually caused by a tragic accident.

When a ship explodes in a port, the first assumption is that terrorists attacked, but that is not always the case. On April 14, 1944, cargo ship Fort Stikine exploded in a berth in the docks of Bombay, India, which is now known as Mumbai. The catastrophic explosion killed 1,300 people and injured another 3,000. It’s possible that the reason it was considered terrorists, or in this case, Japanese sabotage, was because the incident happened during World War II. Nevertheless, the explosion was actually caused by a tragic accident.

The ship, The Fort Stikine was a Canadian-built steamship weighing 8,000 tons. On February 24, Fort Stikine left Birkenhead, England, making a stop in Karachi, Pakistan, before continuing on to dock at Bombay. The cargo on Fort Stikine that day included hundreds of cotton bales, gold bullion and, most notably, 300 tons of trinitrotoluene, better known as TNT or dynamite. I’m sure you can begin to get a picture of what might have triggered this tragic accident. Despite the well-known fact that cotton bales were prone to combustion, the  cotton was stored one level below the dynamite. I’m sure that with a little imagination, you can probably guess what happened next.

cotton was stored one level below the dynamite. I’m sure that with a little imagination, you can probably guess what happened next.

While the ship was being loaded with her cargo, someone noticed smoke coming from the cotton bales. Firefighters were sent to investigate, but emergency measures, such as flooding that part of the ship, were not immediately taken. Instead, about 60 firefighters tried to put out the fire with hoses throughout the afternoon. For some reason, the TNT was not unloaded during the firefighting efforts, creating a recipe for disaster. Before long, it became clear that the firefighters were not going to be able to get control of the fire, and they were ordered off the ship, but they kept dousing the fire from the docks. Unfortunately, their efforts were in vain. The TNT ignited, and at 4:07pm, and the resulting explosion rocked the bay area. The initial force of the blast actually lifted a nearby 4,000-ton ship from the bay onto the land. Windows shattered up to a mile away. A 28-pound gold bar from the Fort Stikine, worth many thousands of dollars, was found a mile away. Everyone in close vicinity of the ship was killed.

In addition to the Fort Stikine, twelve other ships at the docks were destroyed and many more were seriously damaged. The initial blast threw burning debris all over the port. Fires broke out, causing further explosions. In

desperation, military troops were brought in to fight the raging fires and some buildings were demolished just to stop it from spreading. For three days after the explosion, the main business center of Bombay was not safe for anyone to be in. A valuable lesson was learned, but at a horrible price. So many lives lost to learn that cotton and TNT should probably never be on the same ship, but if they are, the cotton should never be stored right below the TNT.

desperation, military troops were brought in to fight the raging fires and some buildings were demolished just to stop it from spreading. For three days after the explosion, the main business center of Bombay was not safe for anyone to be in. A valuable lesson was learned, but at a horrible price. So many lives lost to learn that cotton and TNT should probably never be on the same ship, but if they are, the cotton should never be stored right below the TNT.