World War I

After the November 11, 1918 German surrender in World War I, the German fleet was interned at Scapa Flow under the terms of the Armistice of 11 November, while negotiations took place over its fate. There was talk of the fleet being divided between the Allied nations, and there were those who really wanted that, but this brought the fear that the British would seize the ships, and the Germans worried that if the German government at the time might rejected the Treaty of Versailles and resumed the war effort, the newly confiscated German ships could be used against Germany. Amid all the speculation, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter decided to scuttle the fleet.

After the November 11, 1918 German surrender in World War I, the German fleet was interned at Scapa Flow under the terms of the Armistice of 11 November, while negotiations took place over its fate. There was talk of the fleet being divided between the Allied nations, and there were those who really wanted that, but this brought the fear that the British would seize the ships, and the Germans worried that if the German government at the time might rejected the Treaty of Versailles and resumed the war effort, the newly confiscated German ships could be used against Germany. Amid all the speculation, Admiral Ludwig von Reuter decided to scuttle the fleet.

Scapa Flow was a naval base in the Orkney Islands in Scotland. When the German ships arrived, they had full crews and in all, there were more than 20,000 German sailors aboard, the number of sailors was reduced in the ensuing months. When the full fleet was at Scapa Flow, there were 74 ships there during negotiations between the Allies and Germany over a peace treaty that would become Versailles. The discussion was about what to do with the ships, since they didn’t really want Germany to have a full fleet ready, should they decide to wage war again. The French and Italians wanted a portion of the fleet, but the British wanted them destroyed. They were concerned about their own naval superiority, should the ships be distributed among the other Allied nations.

The Germans didn’t want their ships in the hand of their enemies, so Admiral Ludwig von Reuter began to prepare for the scuttling in May 1919, after hearing about the potential terms of the Versailles Treaty. Shortly before the treaty was signed on June 21, Reuter sent the signal to his men. The men began opening flood valves, smashing water pipes, and opening sewage tanks. As the scuttle was taking place, nine German crew members who abandoned ship and attempted to come ashore were shot by British forces. As the ships were being scuttled, the intervening British guard ships were able to beach some of the ships. In all, 52 of the 74 ships were sunk. While he wouldn’t say so out loud, British Admiral Wemyss was delighted that the ships were

sunk, because that meant they wouldn’t be distributed to the French and Italians navies. Since the scuttling, many ships have been refloated and salvaged in the years since. Nevertheless, some remain in the seas at Scapa Flow. Those that remain are popular diving sites and a source of low-background steel.

sunk, because that meant they wouldn’t be distributed to the French and Italians navies. Since the scuttling, many ships have been refloated and salvaged in the years since. Nevertheless, some remain in the seas at Scapa Flow. Those that remain are popular diving sites and a source of low-background steel.

Sometimes, what seems like a necessary change, and what might have been done with good intentions, ends up being far more detrimental than helpful. In the United States, from 1879 to 1933 our monetary system was based on and utilized gold. The lone exception to that was the embargo on gold exports during World War I. With the gold standard, creditors had the right to demand payment in gold. It was a stable and tangible source of income and payment, and it ensured that the borrower actually had the funds to make the payment. The bank failures during the Great Depression of the 1930s frightened the public, causing them to begin hoarding gold, making the “payment in gold” policy untenable, furthering the panic. On June 5, 1933, Congress enacted a joint resolution nullifying the right of creditors to demand payment in gold, thereby taking the United States off the gold standard. That meant that our currency was no longer backed by gold. This may not have seemed like a bad solution at the time, but it certainly opened the door for a number of huge problems later.

Sometimes, what seems like a necessary change, and what might have been done with good intentions, ends up being far more detrimental than helpful. In the United States, from 1879 to 1933 our monetary system was based on and utilized gold. The lone exception to that was the embargo on gold exports during World War I. With the gold standard, creditors had the right to demand payment in gold. It was a stable and tangible source of income and payment, and it ensured that the borrower actually had the funds to make the payment. The bank failures during the Great Depression of the 1930s frightened the public, causing them to begin hoarding gold, making the “payment in gold” policy untenable, furthering the panic. On June 5, 1933, Congress enacted a joint resolution nullifying the right of creditors to demand payment in gold, thereby taking the United States off the gold standard. That meant that our currency was no longer backed by gold. This may not have seemed like a bad solution at the time, but it certainly opened the door for a number of huge problems later.

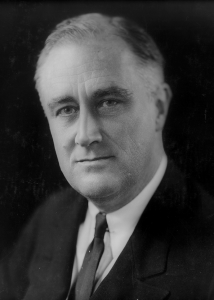

President Roosevelt had seen how this worked when Britain was facing similar pressures, and they decided to drop the gold standard in 1931. So, when the Great Depression hit, Roosevelt decided to implement it in the US. Soon after taking office in March 1933, President Roosevelt declared a nationwide bank moratorium in order to prevent a run on the banks by consumers lacking confidence in the economy. At the same time, he forbade banks from paying out gold or to exporting it. He based his decision on the Keynesian economic theory, which states that one of the best ways to fight off an economic downturn is to inflate the money supply. If the amount of gold held by the Federal Reserve is increased, it would in turn increase its power to inflate the money supply.

With that in mind, Roosevelt, on April 5, 1933, ordered all gold coins and gold certificates in denominations of more than $100 turned in for other money. The order required all persons to deliver all gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates owned by them to the Federal Reserve by May 1, 1933. In exchange, they were to be given $20.67 per ounce. I’m sure it seemed like a good deal, so the people complied. By May 10, the government had taken in $300 million of gold coin and $470 million of gold certificates. Congress two months later, enacted a joint resolution repealing the gold clauses in many public and private obligations that required the debtor to repay the creditor in gold dollars of the same weight and fineness as those borrowed. To complete the inflation process, in 1934, the government price of gold was increased to $35 per ounce, effectively increasing the gold on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheets by 69 percent. This increase in assets allowed the Federal Reserve to further inflate the money supply. So, with a stroke of the pen, the Federal Reserve, and thereby the government increased their wealth by 69%…overnight.

The $35 per ounce value of gold held August 15, 1971, when President Richard Nixon announced that the United States would no longer convert dollars to gold at a fixed value, thus completely abandoning the gold standard. Now I’m not an economist, but if I understand this correctly, it was at that point that the United States, as well as many other nations, began using what is known as “Fiat Money.” Fiat money is “a type of currency that is not backed by a precious metal, such as gold or silver. Fiat money is an intrinsically valueless object or record that is accepted widely as a means of payment. Accordingly, the value of fiat money is greater than the value of its metal or paper content.” It is designated by the issuing government to be legal

tender and it was authorized by government regulations, which means that the government could decide what its value would be. That would render the money to be worthless. Not that it changed much in the amounts of Fiat money in use at the time, but in 1974, President Gerald Ford signed legislation that permitted Americans to own gold bullion again.

tender and it was authorized by government regulations, which means that the government could decide what its value would be. That would render the money to be worthless. Not that it changed much in the amounts of Fiat money in use at the time, but in 1974, President Gerald Ford signed legislation that permitted Americans to own gold bullion again.

After World War I ended, war weary Americans decided that we needed to isolate ourselves from the rest of the world to a degree, in order to protect ourselves. Of course, that didn’t stop people from other countries from wanting to immigrate to the United States. The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act reflected that desire. Americans wanted to push back and distance ourselves from Europe amid growing fears of the spread of communist ideas. The new law seemed the best way to accomplish that. Unfortunately, the law also reflected the pervasiveness of racial discrimination in American society at the time. As more and more largely unskilled and uneducated immigrants tried to come into America, many Americans saw the enormous influx of immigrants during the early 1900s as causing unfair competition for jobs and land.

After World War I ended, war weary Americans decided that we needed to isolate ourselves from the rest of the world to a degree, in order to protect ourselves. Of course, that didn’t stop people from other countries from wanting to immigrate to the United States. The Johnson-Reed Immigration Act reflected that desire. Americans wanted to push back and distance ourselves from Europe amid growing fears of the spread of communist ideas. The new law seemed the best way to accomplish that. Unfortunately, the law also reflected the pervasiveness of racial discrimination in American society at the time. As more and more largely unskilled and uneducated immigrants tried to come into America, many Americans saw the enormous influx of immigrants during the early 1900s as causing unfair competition for jobs and land.

Under the new law, immigration was to remain open to those with a “college education and/or special skills, but entry was denied disproportionately to Eastern and Southern Europeans and Japanese.” At the same time, the legislation allowed for more immigration from Northern European nations such as Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavian countries. The law also set a quota that limited immigration to two percent of any given nation’s residents already in the US as of 1890, a provision designed to maintain America’s largely Northern European racial composition. In 1927, the “two percent rule” was eliminated and a cap of 150,000 total immigrants annually was established. While this was more fair all around, it particularly angered Japan. In 1907, Japan and US President Theodore Roosevelt had created a “Gentlemen’s Agreement,” which included more liberal immigration quotas for Japan. Of course, that was unfair to other nations looking to send immigrants to the United States. Strong US agricultural and labor interests, particularly from California, had already pushed through a form of exclusionary laws against Japanese immigrants by 1924, so they favored the more restrictive legislation signed by Coolidge.

Of course, the Japanese government felt that the American law as an insult and protested by declaring May 26  a “National Day of Humiliation” in Japan. With that, Japan experienced a wave of anti-American sentiment, inspiring a Japanese citizen to commit suicide outside the American embassy in Tokyo in protest. That created more anti-American sentiment, but in the end, it made no difference. On May 26, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924 into law. It was the most stringent and possibly the most controversial US immigration policy in the nation’s history up to that time. Despite becoming known for such isolationist legislation, Coolidge also established the Statue of Liberty as a national monument in 1924.

a “National Day of Humiliation” in Japan. With that, Japan experienced a wave of anti-American sentiment, inspiring a Japanese citizen to commit suicide outside the American embassy in Tokyo in protest. That created more anti-American sentiment, but in the end, it made no difference. On May 26, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924 into law. It was the most stringent and possibly the most controversial US immigration policy in the nation’s history up to that time. Despite becoming known for such isolationist legislation, Coolidge also established the Statue of Liberty as a national monument in 1924.

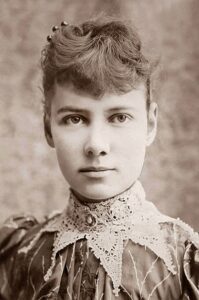

When Elizabeth Jane Cochrane was born on May 5, 1864, there were things that women couldn’t do. It was a man’s world, after all. Not much had changed by the time she was eighteen years old. She was living in Pittsburgh when the local newspaper published an article titled “What Girls are Good For” and according to the article, the answer was having babies and keeping house. These days such an article would have brought immediate outrage, protests, and the author practically strung up. Due to the times, the author would have gotten away with it, but in this case, Elizabeth Cochrane saw it and was very displeased. She was displeased enough, in fact, that she wrote an anonymous rebuttal.

When Elizabeth Jane Cochrane was born on May 5, 1864, there were things that women couldn’t do. It was a man’s world, after all. Not much had changed by the time she was eighteen years old. She was living in Pittsburgh when the local newspaper published an article titled “What Girls are Good For” and according to the article, the answer was having babies and keeping house. These days such an article would have brought immediate outrage, protests, and the author practically strung up. Due to the times, the author would have gotten away with it, but in this case, Elizabeth Cochrane saw it and was very displeased. She was displeased enough, in fact, that she wrote an anonymous rebuttal.

Strangely, the paper’s editor was quite impressed with her rebuttal. He immediately ran an ad in his paper asking the writer to identify herself. Boldly, Elizabeth contacted him, and he hired her on the spot. I’m quite sure that she was not expecting that at all. Still, in this “man’s world” she could not really let anyone know that she was the writer…and maybe that wasn’t exactly a bad thing. Going up against the men is such an argument using her own name might bring some unwanted attention. After all, things were in the very early stages of women’s rights. At that time, most women were still housewives…or schoolteachers, librarians, seamstresses, and such, if they had to work outside the home. So, it was customary at that time for female reporters to use pen names. To top it off, she wasn’t even allowed to pick out her own pen name. The editor gave her one that he took from a Stephen Foster song…Nellie Bly, and it would actually make her famous…as Nellie Bly anyway.

Bly’s passion was investigative reporting, but once again, she found herself stumbling over the whole “man’s world” concept. While she was given work, the paper usually assigned her to more “feminine” subjects…things like theater and fashion. Still, they couldn’t keep her under their thumb very well. After writing a controversial series of articles exposing the working conditions of female factory workers, and after again being relegated to reporting on society functions and women’s hobbies…at age 21 Bly left for Mexico on a dangerous and unprecedented (for a woman) assignment to report of the conditions of the working-class people there. It didn’t take long for her reporting to get her in trouble with the local authorities. Wisely, Bly fled Mexico, but didn’t give up on her story. She later published her dispatches into a popular book.

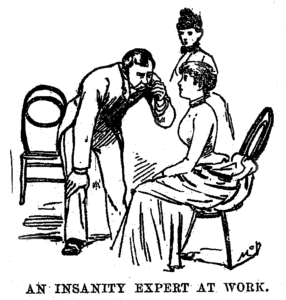

By the time Bly was 23, she had established a reputation for being a daring and provocative reporter. This drew  the attention of Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, where she was hired to basically work under cover. It was the assignment that made her famous. In order to investigate the conditions inside New York’s “Women’s Lunatic Asylum,” Bly took on a fake identity (not really a new concept for someone using a pen name to write), checked into a women’s boarding house, and faked insanity. Bly was so convincing that she soon found herself committed to the asylum. I would personally find that a scary situation, but Bly was dedicated. The report she published of her ten days there was a sensation and led to important reforms in the treatment of the mentally ill.

the attention of Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, where she was hired to basically work under cover. It was the assignment that made her famous. In order to investigate the conditions inside New York’s “Women’s Lunatic Asylum,” Bly took on a fake identity (not really a new concept for someone using a pen name to write), checked into a women’s boarding house, and faked insanity. Bly was so convincing that she soon found herself committed to the asylum. I would personally find that a scary situation, but Bly was dedicated. The report she published of her ten days there was a sensation and led to important reforms in the treatment of the mentally ill.

Nellie Bly was a woman to be remembered. When she was 24, she undertook her most sensational assignment yet: a solo trip around the world inspired by Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days. Ready to go at the drop of a hat, Bly was given only two days’ notice, before she set out on November 14, 1889. She packed a travel bag with her toiletries and a change of underwear, tied her purse around her neck, and she was off. Pulitzer’s competitor, the New York Cosmopolitan, took that as a challenge and immediately sent out one of its reporters, Elizabeth Bisland, to race Bly, but traveling in the opposite direction. As Pulitzer had hoped, the stunt was a publicity bonanza. Readers gobbled up the regular reports on Bly’s journey and the paper sponsoring a contest for readers to guess the exact time of Bly’s return. The winning guess would be awarded an expense-paid trip to Europe.

Bly made her triumphant return just seventy-two days later, four and half days ahead of Bisland. She had successfully circumnavigated the globe, while traveling alone almost the entire time. It was a world record…the fastest any human had ever made the journey. Suddenly, Nellie Bly was an international celebrity. I still wonder if there was some regret that she was still using the pen name, or maybe it gave her a degree of anonymity, until people recognized her, that is.

After leading an almost insanely adventurous life, Bly decided to retire…so to speak. When she was 31 years old, Bly married industrialist Robert Seaman, a 73-year-old millionaire. With her marriage, she left behind her journalism career and her pen name and became Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman. She helped run the Seaman family business. While working as an industrialist, she patented two inventions, but she knew that business was not really her forte, and sadly, under her leadership the company went bankrupt. I’m sure that with all her life

successes, that was a devastating failure for her. With the outbreak of World War I broke out, she returned to journalism, becoming one of the first women reporters to work in an active war zone. I have no doubt that Nellie Bly (Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman) could have done so many more remarkable things in her life, but sadly, her remarkable life ended on January 27, 1922, when she died of pneumonia in New York at age 57.

successes, that was a devastating failure for her. With the outbreak of World War I broke out, she returned to journalism, becoming one of the first women reporters to work in an active war zone. I have no doubt that Nellie Bly (Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman) could have done so many more remarkable things in her life, but sadly, her remarkable life ended on January 27, 1922, when she died of pneumonia in New York at age 57.

I think many people realize the usefulness of a dog as something other than a pet. Over the years, there have been seeing eye dogs, service dogs, and one I hadn’t heard of before…mercy dogs. During World War I, some 50,000 dogs were “employed” by both sides of the conflict as soldiers on both sides of the conflict as mercy dogs. You might wonder just what a mercy dogs is. While it is a rather sad one, the job the dogs had was actually had a very important job in the military. During battle, these dogs were sent out to find and help wounded men on the battlefield. They were very good at their jobs.

I think many people realize the usefulness of a dog as something other than a pet. Over the years, there have been seeing eye dogs, service dogs, and one I hadn’t heard of before…mercy dogs. During World War I, some 50,000 dogs were “employed” by both sides of the conflict as soldiers on both sides of the conflict as mercy dogs. You might wonder just what a mercy dogs is. While it is a rather sad one, the job the dogs had was actually had a very important job in the military. During battle, these dogs were sent out to find and help wounded men on the battlefield. They were very good at their jobs.

On their backs, the dogs carried medical supplies. They sought out injured soldiers. If a soldier was gravely wounded, the dogs would tear off a piece of his uniform, carry it back to camp, and help other soldiers to locate the man. Sometimes, the dogs found men who were beyond saving. In that case, they lay down next to him, so that the dying soldier didn’t have to die alone. These were true acts of mercy, and these dongs had true compassion for these men.

Mercy dogs were also known as ambulance dogs, Red Cross dogs, or casualty dogs. These dogs actually served in a paramedical role in the military…most notably during World War I, but also in World War II, and the Korean War. They have been credited with saving thousands of lives. The dogs were well trained and well suited for  trench warfare. They were often sent out after large battles, where they would seek out wounded soldiers. They were also trained to guide combat medics to soldiers who required extensive care.

trench warfare. They were often sent out after large battles, where they would seek out wounded soldiers. They were also trained to guide combat medics to soldiers who required extensive care.

The first mercy dogs were actually trained by the German army in the late 19th century. The program to train mercy dogs in 1895 begun by Jean Bungartz in Germany was described as a “novel experiment” by those who knew about it. I’m sure they didn’t think it would actually work. Nevertheless, by 1908, Italy, Austria, and France had joined Germany in training programs for mercy dogs. Germany had around 6,000 trained dogs by the beginning of World War I. Many of the trained dogs were ambulance dogs. The German army called them Sanitätshunde or medical dogs. Germany is estimated to have used a total of 30,000 dogs during the war, mainly as messengers and ambulance dogs. Amazingly, only 7,000 of those were killed. Somehow, I would have expected there to be more deaths among the dogs. It is estimated that upwards of 50,000 dogs were successfully used by all of the nations involved in the war.

When World War I started, Britain did not have a program for training military dogs. Edwin Hautenville Richardson, who was an officer in the British Army had experience working with military dogs and had advocated for the start of a military program since 1910, but his program was not taken seriously. Nevertheless, he had trained several dogs as ambulance dogs on his own. He quickly offered them to the British Army. The army did not accept his offer, for some bizarre reason, so he gave them to the British Red Cross. As a result of his advocacy, Britain created a British War Dog School with Richardson as the commander. The school eventually trained more than 200 dogs. The British War Dog School was a grand success.

It is estimated that as many as 10,000 dogs served as mercy dogs in World War I, and are credited with saving thousands of lives, including at least 2,000 in France and 4,000 wounded German soldiers. There were several dogs that were specifically honored for their work. “Captain” was credited for finding 30 soldiers in one day, and “Prusco” for finding 100 men in just one battle. Both of these were French dogs. “Prusco” was known to drag soldiers into ditches as a safe harbor while he went to summon rescuers. Sadly, many French dogs were killed in the line of duty, and the program was discontinued. I suppose they thought it was inhumane, but I’m sure the dogs knew they were doing important work.

Charles Askins, Jr was an American lawman, US Army officer, and writer. He served in law enforcement, mostly with the US Forest Service and Border Patrol, in the American Southwest prior to the Second World War. He was also known as Colonel Charles “Boots” Askins. He was the son of Major Charles “Bobo” Askins, a sportswriter and Army officer who served in the Spanish American War and World War I, and he was quickly following in his father’s footsteps.

Charles Askins, Jr was an American lawman, US Army officer, and writer. He served in law enforcement, mostly with the US Forest Service and Border Patrol, in the American Southwest prior to the Second World War. He was also known as Colonel Charles “Boots” Askins. He was the son of Major Charles “Bobo” Askins, a sportswriter and Army officer who served in the Spanish American War and World War I, and he was quickly following in his father’s footsteps.

Askins was born in Nebraska on October 28, 1987. The family moved to Oklahoma, where “Boots” Askins was raised. He had several careers in his life, but the first job was fighting forest fires in Montana. Then in 1927, the US Forest Service transferred him to New Mexico to be a Park Ranger at the Kit Carson National Forest. Askins fought fires in New Mexico, until 1930, when he was recruited by the US Border Patrol. Askins wrote in his memoir Unrepentant Sinner, that he had been involved in at least one gunfight every week. I’m sure that work on the US border brought with it a common risk of gunfights. Askins showed great skill, and during his service in the Border Patrol, he won many pistol championships. He was promoted to leader of the Border Patrol’s handgun skills program.

When the United States entered World War II, Askins served in the US Army as a battlefield recovery officer.  His work took him to North Africa, Italy, and he was in France on D-day. After being discharged from the Army following World War II, he spent several years in Spain as an attaché to the American embassy, helping Franco rebuild Spain’s munition plants. When he completed his assignment in Spain, he was reassigned to Vietnam, where he trained South Vietnamese soldiers in shooting and airborne operations. Askins had an exemplary career in the Army and while he was in the military, he indulged in big game hunting at every opportunity. He continued hunting after his retirement. In his lifetime, he held several big game hunting records, as well as two national pistol championships, an American Handgunner of the Year award, and innumerable smaller titles in competitive shooting. Askins spent his final years in the military at Fort Sam Houston, and he retired to San Antonio, Texas.

His work took him to North Africa, Italy, and he was in France on D-day. After being discharged from the Army following World War II, he spent several years in Spain as an attaché to the American embassy, helping Franco rebuild Spain’s munition plants. When he completed his assignment in Spain, he was reassigned to Vietnam, where he trained South Vietnamese soldiers in shooting and airborne operations. Askins had an exemplary career in the Army and while he was in the military, he indulged in big game hunting at every opportunity. He continued hunting after his retirement. In his lifetime, he held several big game hunting records, as well as two national pistol championships, an American Handgunner of the Year award, and innumerable smaller titles in competitive shooting. Askins spent his final years in the military at Fort Sam Houston, and he retired to San Antonio, Texas.

Askins inherited his writing skills from his father, “Bobo” Askins. “Boots” Askins was a creative writer, with a  number of books and over 1,000 magazine articles on subjects related to hunting and shooting. His writing career spanned 70 years, from 1929 until his death in March of 1999. While he was an excellent, his writings were considered controversial, mostly because he liked to graphically describe the numerous fatal shootings in his law enforcement and military careers, stating he had killed “27, not counting blacks and Mexicans.” He even once described himself as possibly a “psychopathic killer, and that he hunted animals so avidly because he was not allowed to hunt men anymore.” I suppose his killings were “justified” but maybe not really ethical. Still, many of them were necessary. He died on March 2, 1999, at the age of 91.

number of books and over 1,000 magazine articles on subjects related to hunting and shooting. His writing career spanned 70 years, from 1929 until his death in March of 1999. While he was an excellent, his writings were considered controversial, mostly because he liked to graphically describe the numerous fatal shootings in his law enforcement and military careers, stating he had killed “27, not counting blacks and Mexicans.” He even once described himself as possibly a “psychopathic killer, and that he hunted animals so avidly because he was not allowed to hunt men anymore.” I suppose his killings were “justified” but maybe not really ethical. Still, many of them were necessary. He died on March 2, 1999, at the age of 91.

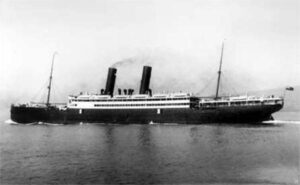

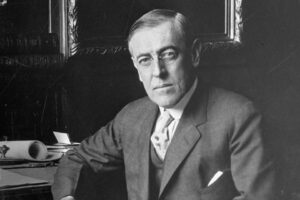

The SS California, owned by Anchor Line Steamship Company; a Scottish merchant shipping company that was founded in 1855 and dissolved in 1980; departed New York on January 29, 1917, bound for Glasgow, Scotland, with 205 passengers and crewmembers on board. While the trip should have been a pleasant journey, world events would soon happen that would change everything in an instant. On February 3, 1917, United States President Woodrow Wilson gave a speech in which he “broke diplomatic relations with Germany and warned that war would follow if American interests at sea were again assaulted.” Of course, all ship sailing the seas, especially those departing or arriving in the United States, or any that had US passengers were warned about the possibility of a German attack.

The SS California, owned by Anchor Line Steamship Company; a Scottish merchant shipping company that was founded in 1855 and dissolved in 1980; departed New York on January 29, 1917, bound for Glasgow, Scotland, with 205 passengers and crewmembers on board. While the trip should have been a pleasant journey, world events would soon happen that would change everything in an instant. On February 3, 1917, United States President Woodrow Wilson gave a speech in which he “broke diplomatic relations with Germany and warned that war would follow if American interests at sea were again assaulted.” Of course, all ship sailing the seas, especially those departing or arriving in the United States, or any that had US passengers were warned about the possibility of a German attack.

February 7, 1917, found the SS California some 38 miles off the coast of Fastnet, Ireland, when the ship’s captain, John Henderson, spotted a submarine off his ship’s port side at a little after 9am. I can only imagine the sinking feeling the captain must have felt at that moment. The Germans were not known for any kind of compassion, and they didn’t particularly care if this was a passenger ship. They figured that the ship might be carrying weapons, and they actually might have been. Captain Henderson ordered the gunner at the stern of the ship to fire in defense, if necessary. Unfortunately, there would not be time to do so, because moments later and without warning, the submarine fired two torpedoes at the ship. The first torpedo missed, but the second torpedo exploded into the port side of the steamer, killing five people instantly. The explosion of that torpedo was so violent and devastating that it caused the 470-foot, 9,000-ton steamer to sink just nine minutes later. The crew quickly sent desperate S.O.S. calls, but the best they could hope for was a hasty arrival of rescue ships. Time was simply not on their side, as 38 people drowned after the initial explosion, and with the initial 5 who died when the torpedo impacted the ship, a total of 43 died. It was an act of war by the Germans.

The Germans were known for this type of blatant attack, in complete defiance of Wilson’s warnings. It’s almost as if they were simply crazed with hatred. Because of Wilson’s warnings about the consequences of unrestricted submarine warfare and the subsequent discovery and release of the Zimmermann telegram, the Germans reached out to the foreign minister to the Mexican government involving a possible Mexican-German alliance in the event of a war between Germany and the United States. That caused Wilson and the United States to take the final steps towards war. On April 2, 1917, Wilson delivered his war message before Congress. It was this action that brought about the United States’ entrance into the First World War, which came about just four days later.

The Germans were known for this type of blatant attack, in complete defiance of Wilson’s warnings. It’s almost as if they were simply crazed with hatred. Because of Wilson’s warnings about the consequences of unrestricted submarine warfare and the subsequent discovery and release of the Zimmermann telegram, the Germans reached out to the foreign minister to the Mexican government involving a possible Mexican-German alliance in the event of a war between Germany and the United States. That caused Wilson and the United States to take the final steps towards war. On April 2, 1917, Wilson delivered his war message before Congress. It was this action that brought about the United States’ entrance into the First World War, which came about just four days later.

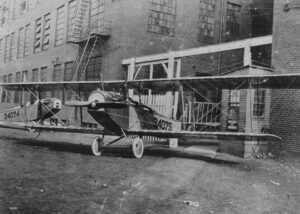

In World War I, airplanes were a relatively new item. The Wright brothers made their first sustained flight on December 17, 1903, so by 1918, they were still barely more than a novelty, but that didn’t matter. The world needed these machines, if the Allied countries were to win World War I. I’m sure that no one really knew how these new machines were going to work out, and I can only imagine how the pilots that had to fly those first planes felt about not only flying in them, but doing combat in them. One of those first crew members was Stephen W Thompson, a 24-year-old gunner on a French aircraft in February 1918.

In World War I, airplanes were a relatively new item. The Wright brothers made their first sustained flight on December 17, 1903, so by 1918, they were still barely more than a novelty, but that didn’t matter. The world needed these machines, if the Allied countries were to win World War I. I’m sure that no one really knew how these new machines were going to work out, and I can only imagine how the pilots that had to fly those first planes felt about not only flying in them, but doing combat in them. One of those first crew members was Stephen W Thompson, a 24-year-old gunner on a French aircraft in February 1918.

Thompson was born on March 20, 1894, in West Plains, Missouri. When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Thompson was a senior in electrical engineering at the University of Missouri. Men were needed to go and fight, so the school announced that seniors who joined the military before graduation would receive their diplomas in June. Being a loyal American, Thompson enlisted in the Army. He was sent for basic training at Fort Riley, Kansas, and by June he was sent to Fort Monroe, Virginia for training in the Coast Artillery Corps. The train ride to his post would change his life forever, when he spotted an airplane in the sky. It was the first one he had ever seen, and when he got the opportunity, he went to the flying field, the Curtis School at Newport News, and asked if he could take a ride. He figured it might be the only chance he would get, and he didn’t want to miss out. Thomas Scott Baldwin, who had been a famous performer in his own balloons and dirigibles, was in charge and he agreed to give Thompson a ride. The plane  was a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny and the pilot was Edward Stinson, a prominent flyer at the time who later founded the Stinson Aircraft Company.

was a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny and the pilot was Edward Stinson, a prominent flyer at the time who later founded the Stinson Aircraft Company.

After his ride, in which Stinson did a number of aerobatic maneuvers, including looping the loop five times in a row, Thompson said that the only thing that kept him from falling out of the plane at the top of the last loop was the lap belt. I can only imagine how he felt, but that flight changed Thompson’s whole life. He decided to apply for duty in the Air Service. He was accepted, and on February 5, 1918, flying as a gunner on a French aircraft in February 1918, he became the first member of the United States military to shoot down an enemy aircraft. He was not the first person to shoot down another aircraft, because Kiffin Rockwell achieved an earlier aerial victory as an American volunteer member of the French Lafayette Escadrille in 1916. Nevertheless, Thompson was the first “official soldier” to do so. That day, the 1st Aero Squadron had not yet begun combat operations, and Thompson visited a French unit with a fellow member of the 1st Aero Squadron. The men were invited to fly as gunner-bombardiers with the French on a bombing raid over Saarbrücken, Germany. Well, nobody had to ask them twice. The run was successful, but after they had dropped their bombs, the squadron was attacked by Albatros D III fighters. Immediately taking action, Thompson shot down one of them, thereby  carrying out the first aerial victory by any member of the US military. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm for the action.

carrying out the first aerial victory by any member of the US military. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm for the action.

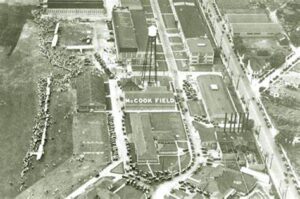

After the war Thompson worked at McCook Field for several years as an engineer. Today, McCook Field is Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Following his time at McCook Field, he became a high school mathematics teacher. During World War II, he taught preflight and meteorology. He maintained an interest in aviation and in 1940 he received US Patent Number 2,210,642 for a tailless flying wing. He died on October 9, 1977, in Dayton, Ohio at age 83.

As kids grow up, you suddenly find yourself looking at a whole new person. It’s not just the normal changes that happen as kids grow, like height and a new grown up look about them. Suddenly, they have interests that are very different than yours. Sometimes that could be a bad thing, but for my grandnephew, Ethan Hadlock those new interests are different than many kids his age. Ethan is really into history, and especially World War I. History is often the last thing kids are interested in, but for Ethan, history and especially World War I are the coolest things. He even wanted his friend birthday party to have a World War I theme. His mom, Chelsea Hadlock did a great job creating that for him.

As kids grow up, you suddenly find yourself looking at a whole new person. It’s not just the normal changes that happen as kids grow, like height and a new grown up look about them. Suddenly, they have interests that are very different than yours. Sometimes that could be a bad thing, but for my grandnephew, Ethan Hadlock those new interests are different than many kids his age. Ethan is really into history, and especially World War I. History is often the last thing kids are interested in, but for Ethan, history and especially World War I are the coolest things. He even wanted his friend birthday party to have a World War I theme. His mom, Chelsea Hadlock did a great job creating that for him.

Ethan is the grandson of a retired cop, my brother-in-law, Chris Hadlock and an uncle who is a cop, Jason Sawdon, so security is important to him. With that in mind, Ethan has joined the club Cyber Patriots which teaches kids to check websites and things for cyber security threats. I think that is an amazing club to have. These kinds of threats are a very real part of life these days, and everyone needs to know about it, especially kids. Ethan is also in a welding class right now and he really loves it! That isn’t surprising either, considering his great grandpa, my dad, Allen Spencer was a welder by trade. Christmas brought Ethan a couple of new horizons to try. He was give golf lessons, and he can’t wait to start them and learn the game of golf. He also

received a World War I tiger tank Lego set. It is an RC car that he will have to put together. He can’t wait to get going on that. Everyone loves Legos, and Ethan is no exception. He’s really good at Rubik’s cubes too! He can put them right really quickly!!

received a World War I tiger tank Lego set. It is an RC car that he will have to put together. He can’t wait to get going on that. Everyone loves Legos, and Ethan is no exception. He’s really good at Rubik’s cubes too! He can put them right really quickly!!

Ethan loves animals. The Hadlock family is a family of “dog lovers” and Ethan loves all of them. He is always willing to help with the animals, whether it is feeding them, playing with them, or chasing them down when they don’t want to come in the house. Recently, his aunt, Kellie Hadlock hired him to watch her bird. Ethan quickly accepted the job, but really thought it was a volunteer job. When Kellie paid him, he was so thankful that he honestly thanked her every time he saw her for like a week!! It was so sweet! Ethan is no stranger to volunteer work either. Each summer, he volunteers at the Vacation Bible School at his Aunt Lindsay Moore’s church in Laramie! He always works in the recreation area and gets to do things like shoot water rockets!! He always has a blast!! Being the only boy among the cousins, Ethan is always ready to take care of all his cousins too! He watches out for them!

Now that Ethan is 15 years old, he is ready to take his drivers ed test!! He is very excited about learning to drive. He and his mom went to get his study books a while back, and he is ready for the test on Monday. I can’t

believe that this sweet boy, who picks on everyone just like his dad, Ryan Hadlock, but is always ready to give a hug to anyone in the family, and even seeks out the family for a hug, is old enough to learn to drive. While it may seem impossible in years, it isn’t surprising in size. Ethan is already well on his way to gaining the height of his dad and grandpa, who are both well over six foot. Ethan is close to six foot now, and with a number of years to grow yet. Today is Ethan’s 15th birthday. Happy birthday Ethan!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

believe that this sweet boy, who picks on everyone just like his dad, Ryan Hadlock, but is always ready to give a hug to anyone in the family, and even seeks out the family for a hug, is old enough to learn to drive. While it may seem impossible in years, it isn’t surprising in size. Ethan is already well on his way to gaining the height of his dad and grandpa, who are both well over six foot. Ethan is close to six foot now, and with a number of years to grow yet. Today is Ethan’s 15th birthday. Happy birthday Ethan!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

The RMS Leinster was an Irish ship, which served as the Kingstown-Holyhead mailboat and was operated by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company. In 1895, the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company ordered four steamers for Royal Mail service, named for four provinces of Ireland. The ships were RMS Leinster, RMS Connaught, RMS Munster, and RMS Ulster. The Leinster was a 3,069-ton packet steamship with a service speed of 23 knots. The ship was built at Laird’s in Birkenhead, England. It had two independent four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. She has launched September 12, 1896. In a perfect world, guns would not be needed on a mail ship. Then, during the World War I, the twin-propellered ship was armed with one 12-pounder and two signal guns. The war made this protection necessary. Even with the guns for protection, RMS Leinster, like her sister ships, was vulnerable to the ever present and dangerous German U-Boats. The ship continued her run, until she found herself in the wrong place at the wrong time. RMS Leinster was torpedoed and sunk by the German U-Boat U-123, on October 10, 1918. She sank just outside Dublin Bay at a point 4 nautical miles east of the Kish light.

The RMS Leinster was an Irish ship, which served as the Kingstown-Holyhead mailboat and was operated by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company. In 1895, the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company ordered four steamers for Royal Mail service, named for four provinces of Ireland. The ships were RMS Leinster, RMS Connaught, RMS Munster, and RMS Ulster. The Leinster was a 3,069-ton packet steamship with a service speed of 23 knots. The ship was built at Laird’s in Birkenhead, England. It had two independent four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. She has launched September 12, 1896. In a perfect world, guns would not be needed on a mail ship. Then, during the World War I, the twin-propellered ship was armed with one 12-pounder and two signal guns. The war made this protection necessary. Even with the guns for protection, RMS Leinster, like her sister ships, was vulnerable to the ever present and dangerous German U-Boats. The ship continued her run, until she found herself in the wrong place at the wrong time. RMS Leinster was torpedoed and sunk by the German U-Boat U-123, on October 10, 1918. She sank just outside Dublin Bay at a point 4 nautical miles east of the Kish light.

The ship had, in addition to its crew, a number of civilian mail workers. The exact number of dead is unknown, but researchers from the National Maritime Museum believe it was at least 564. The ship’s log, however, states that she carried 77 crew and 694 passengers on her final voyage. This number would seem more correct to me simply because of the records normally kept in logbooks. There is someone assigned to keep that log, and while they could have done a poor job, it is more unlikely that just trusting the number to a random guess of a historian who came along later. The sinking wasn’t the first attack that had been waged on RMS Leister. She had been previously attacked in the Irish Sea, but the torpedoes missed their target. On October 10, 1918, the manifest included more than 100 British civilians, 22 postal sorters (working in the mail room) and almost 500  military personnel from the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force. Also aboard were nurses from Great Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

military personnel from the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force. Also aboard were nurses from Great Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

Just before 10am, as RMS Leister was sailing east of the Kish Bank in a heavy swell, some of the passengers saw a torpedo approach from the port side and pass in front of the bow. I’m sure a panic ensued, and then a second torpedo followed shortly afterwards. This torpedo struck the ship forward on the port side in the vicinity of the mail room. The ship attempted evasive action, trying to make a U-turn in an attempt to return to Kingstown, but the damage was done. As it began to settle slowly by the bow, RMS Leister sank rapidly, helped along by a third torpedo strike, which caused a huge explosion. Whether the number of victims listed is right or wrong, doesn’t really matter, because either number would make the sinking of RMS Leister, the largest single loss of life in the Irish Sea.

Despite the heavy seas, the crew managed to launch several lifeboats and some passengers clung to life-rafts. The survivors were rescued by HMS Lively, HMS Mallard, and HMS Seal. Among the civilian passengers lost in the sinking were socially prominent people such as Lady Phyllis Hamilton, daughter of the Duke of Abercorn, Robert Jocelyn Alexander, son of Irish composer Cecil Frances Alexander, Reverand John Bartley, the Presbyterian minister of Tralee who was travelling to visit his mortally wounded son in hospital, Thomas Foley and his wife Charlotte Foley (née Barrett) who was the brother-in-law of the world-famous Irish tenor John McCormack who adopted their eldest son, and Richard Moore, only son of British architect Temple Moore. The first member of the Women’s Royal Naval Service to die on active duty, Josephine Carr, was among those who died, as were two prominent officials of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union, James McCarron and Patrick Lynch. Several of the military personnel who died are buried in Grangegorman Military Cemetery.

On October 18, 1918, at 9:10am U-125, outbound from Germany, picked up a radio message requesting advice on the best way to get through the North Sea minefield. The sender was U-123. Extra mines had been added to the minefield since U-123 had made her outward voyage from Germany. As U-125 had just come through the minefield, U-125 radioed back with a suggested route. U-123 acknowledged the message and was never heard from again. The following say, ten days after the sinking of the RMS Leinster, U-123 detonated a mine and sank while trying to cross the North Sea and return to base in Imperial Germany. There were no survivors. In 1991, the anchor of the RMS Leinster was raised by local divers. It was placed near Carlisle Pier and officially dedicated on January 28, 1996.

On October 18, 1918, at 9:10am U-125, outbound from Germany, picked up a radio message requesting advice on the best way to get through the North Sea minefield. The sender was U-123. Extra mines had been added to the minefield since U-123 had made her outward voyage from Germany. As U-125 had just come through the minefield, U-125 radioed back with a suggested route. U-123 acknowledged the message and was never heard from again. The following say, ten days after the sinking of the RMS Leinster, U-123 detonated a mine and sank while trying to cross the North Sea and return to base in Imperial Germany. There were no survivors. In 1991, the anchor of the RMS Leinster was raised by local divers. It was placed near Carlisle Pier and officially dedicated on January 28, 1996.