wisconsin

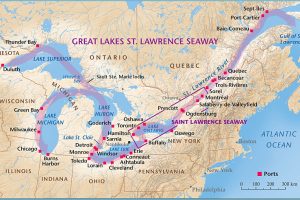

Most people know about the Great Lakes in the north-central United States, but quite possibly, many are not as familiar with the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Nevertheless, the Saint Lawrence Seaway is one of the most important parts of the Great Lakes shipping system. Prior to the Saint Lawrence Seaway there were a number of other canals. In 1871, there were locks on the Saint Lawrence River that allowed transit of vessels 186 feet long, 44 feet 6 inch wide, and 9 feet deep. The First Welland Canal, constructed from 1824–1829, had a minimum lock size of 110 feet long, 22 feet wide, and 8 feet deep, but it was generally too small to allow passage of larger ocean-going ships, which would have eliminated the majority of ships that could ship in quantity. The Welland Canal’s minimum lock size was increased to 150 feet long, 26.5 feet wide, and 9 feet deep for the Second Welland Canal, then to 270 feet long, 45 feet wide, and 14 feet deep with the Third Welland Canal, and to 766 feet long, 80 feet wide, and 30 feet deep with the fourth and current Welland Canal. Still, everyone knew that something else was going to have to be done soon.

Most people know about the Great Lakes in the north-central United States, but quite possibly, many are not as familiar with the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Nevertheless, the Saint Lawrence Seaway is one of the most important parts of the Great Lakes shipping system. Prior to the Saint Lawrence Seaway there were a number of other canals. In 1871, there were locks on the Saint Lawrence River that allowed transit of vessels 186 feet long, 44 feet 6 inch wide, and 9 feet deep. The First Welland Canal, constructed from 1824–1829, had a minimum lock size of 110 feet long, 22 feet wide, and 8 feet deep, but it was generally too small to allow passage of larger ocean-going ships, which would have eliminated the majority of ships that could ship in quantity. The Welland Canal’s minimum lock size was increased to 150 feet long, 26.5 feet wide, and 9 feet deep for the Second Welland Canal, then to 270 feet long, 45 feet wide, and 14 feet deep with the Third Welland Canal, and to 766 feet long, 80 feet wide, and 30 feet deep with the fourth and current Welland Canal. Still, everyone knew that something else was going to have to be done soon.

The first proposals for a bi-national comprehensive deep waterway along the Saint Lawrence were made in the 1890s. In the following decades, developers proposed a hydropower project that would be inseparable from the seaway,  the various governments and seaway supporters believed that the deeper water to be created by the hydro project was necessary to make the seaway channels feasible for ocean-going ships, which we all know was an essential part of the shipping business for the United States and the world. United States proposals for development up to and including World War I met with little interest from the Canadian federal government…at least at first. Later, the two national governments submitted Saint Lawrence plans to a group for study. By the early 1920s, both The Wooten-Bowden Report and the International Joint Commission recommended the project.

the various governments and seaway supporters believed that the deeper water to be created by the hydro project was necessary to make the seaway channels feasible for ocean-going ships, which we all know was an essential part of the shipping business for the United States and the world. United States proposals for development up to and including World War I met with little interest from the Canadian federal government…at least at first. Later, the two national governments submitted Saint Lawrence plans to a group for study. By the early 1920s, both The Wooten-Bowden Report and the International Joint Commission recommended the project.

The Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King really wasn’t all for the project, mostly because of opposition to the project in Quebec, in 1932. He and the United States representative finally signed a treaty of intent. The treaty was submitted to the United States Senate in November of 1932 and hearings continued until a vote was taken on March 14, 1934. The majority did vote in favor of the treaty, but it failed to gain the necessary two-thirds vote for ratification. Additional attempts between the governments in the 1930s to forge an agreement Failed due to opposition by the Ontario government of Mitchell Hepburn, and that of Quebec. In 1936, John C Beukema, who was the head of the Great Lakes Harbors Association and a member of the Great Lakes Tidewater Commission, was among a delegation of eight from the Great Lakes states to meet at the White House with United States President Franklin D Roosevelt to get his support for the Seaway project.

After much back and forth wrangling, the two countries agreed that the Saint Lawrence Seaway was a  necessary addition to the Great Lakes shipping industry, and it would later prove to be a vital part of it. In the years that my sister, my parents, and I lived in Superior, Wisconsin, the Saint Lawrence Seaway was something that, at least our parents remember being under construction. The opening ceremony took place on June 26, 1959, and was presided over by United States President Dwight D Eisenhower and Queen Elizabeth II. Once it was opened, it created a navigational channel from the Atlantic Ocean to all the Great Lakes. The seaway, made up of a system of canals, locks, and dredged waterways, extends a distance of nearly 2,500 miles, from the Atlantic Ocean through the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to Duluth, Minnesota, on Lake Superior.

necessary addition to the Great Lakes shipping industry, and it would later prove to be a vital part of it. In the years that my sister, my parents, and I lived in Superior, Wisconsin, the Saint Lawrence Seaway was something that, at least our parents remember being under construction. The opening ceremony took place on June 26, 1959, and was presided over by United States President Dwight D Eisenhower and Queen Elizabeth II. Once it was opened, it created a navigational channel from the Atlantic Ocean to all the Great Lakes. The seaway, made up of a system of canals, locks, and dredged waterways, extends a distance of nearly 2,500 miles, from the Atlantic Ocean through the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to Duluth, Minnesota, on Lake Superior.

These days, as wars are fought, we often see, hear, and read the stories written by embedded reporters. It seems almost commonplace, and yet in reality, whenever these reporters go into a war zone, they are risking almost as much as the soldiers. Of course, the reporters don’t go out to attack the enemy, but because of where they are, and who they are with, they make themselves a target to the enemy too. Even as far back as the World Wars, embedded reporters seemed like a common phenomenon, but who would have thought of an embedded reporter as far back as the Indian wars? I certainly didn’t. Nevertheless, journalists were there. One such journalist, who became famous, mostly because he was killed, was Marcus Kellogg, who was traveling with Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Kellogg was a native of Ontario, Canada before immigrating to New York with his family in 1835. As a young man he mastered the art of the telegraph and went to work for the Pacific Telegraphy Company in Wisconsin. During the Civil War, he felt led toward a different calling. He left his career in telegraphy, and became a journalist. Then in 1873, he again felt the calling to change his life, when he decided to move west to the frontier town of Bismarck in Dakota Territory and became the assistant editor of the Bismarck Tribune.

These days, as wars are fought, we often see, hear, and read the stories written by embedded reporters. It seems almost commonplace, and yet in reality, whenever these reporters go into a war zone, they are risking almost as much as the soldiers. Of course, the reporters don’t go out to attack the enemy, but because of where they are, and who they are with, they make themselves a target to the enemy too. Even as far back as the World Wars, embedded reporters seemed like a common phenomenon, but who would have thought of an embedded reporter as far back as the Indian wars? I certainly didn’t. Nevertheless, journalists were there. One such journalist, who became famous, mostly because he was killed, was Marcus Kellogg, who was traveling with Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Kellogg was a native of Ontario, Canada before immigrating to New York with his family in 1835. As a young man he mastered the art of the telegraph and went to work for the Pacific Telegraphy Company in Wisconsin. During the Civil War, he felt led toward a different calling. He left his career in telegraphy, and became a journalist. Then in 1873, he again felt the calling to change his life, when he decided to move west to the frontier town of Bismarck in Dakota Territory and became the assistant editor of the Bismarck Tribune.

Then, while returning from a trip to the East, Kellogg happened to be on the same train as George Custer and his wife, Elizabeth. Custer was on his way to Fort Abraham Lincoln, near Bismarck, where he was going to lead the 7th Cavalry in a planned assault on several bands of Indians who had refused to be confined to reservations. There journey was delayed by an unusually heavy winter storm. The train became snowbound. Being the expert that he was, Kellogg improvised a crude telegraph key, connected it to the wires running alongside the track, and sent a message ahead to the fort asking for help. Custer’s brother, Tom, arrived soon after with a sleigh to rescue them. Custer had enjoyed being made famous by the nation’s newspapers during the Civil War, and now, as he prepared for what he hoped would be his greatest victory ever, Custer wanted to make sure his glorious deeds would be adequately covered in the press. Initially, Custer had planned to take his old friend Clement Lounsberry, who was Kellogg’s employer at the Tribune, with him into the field with the 7th Cavalry, but after meeting Kellogg, he chose him to go instead, mostly because Custer had been impressed by his resourcefulness with a telegraph key.

That one chance event in the winter of 1876, took Kellogg in an unexpected direction…toward the Little Big Horn. When Custer led his soldiers out of Fort Abraham Lincoln and headed west for Montana on May 31, Kellogg rode with him. During the next few weeks, Kellogg filed three dispatches from the field to the Bismarck Tribune, which in turn passed the stories on to the New York Herald. Wanting to make sure the word got out, Custer also sent three anonymous reports on his progress to the Herald. Kellogg’s first dispatches, dated May 31 and June 12, recorded the progress of the expedition westward. His final report, dated June 21, came from the army’s camp along the Rosebud River in southern Montana, not far from the Little Big Horn River. “We leave the Rosebud tomorrow,” Kellogg wrote, “and by the time this reaches you we will have met and fought the red devils, with what result remains to be seen.” The results, of course, were disastrous. Four days later, Sioux and Cheyenne warriors wiped out Custer and his men along the Little Big Horn River. Kellogg was the only journalist to witness the final moments of Custer’s 7th Cavalry. Had he been able to file a story he would have become a national celebrity, but Kellogg did not live to tell the tale, he died alongside Custer’s soldiers.

On July 6, the Bismarck Tribune printed a special extra edition with a top headline reading: “Massacred: Gen. Custer and 261 Men the Victims.” Further down in the column, in substantially smaller type, a sub-headline reported: “The Bismarck Tribune’s Special Correspondent Slain.” The article went on to report, “The body of Kellogg alone remained unstripped of its clothing, and was not mutilated.” The reporter speculated that this

might have been a result of the Indian’s “respect for this humble shover of the lead pencil.” I doubt that the Sioux and Cheyenne respected Kellogg for his journalistic abilities, but his death in one of the most notorious events in the nation’s history made him something of an martyr among newspapermen. The New York Herald later erected a monument to Kellogg over the supposed site of his grave on the Little Big Horn battlefield. Being an embedded journalist might be exciting, but it’s quite risky too.

might have been a result of the Indian’s “respect for this humble shover of the lead pencil.” I doubt that the Sioux and Cheyenne respected Kellogg for his journalistic abilities, but his death in one of the most notorious events in the nation’s history made him something of an martyr among newspapermen. The New York Herald later erected a monument to Kellogg over the supposed site of his grave on the Little Big Horn battlefield. Being an embedded journalist might be exciting, but it’s quite risky too.

In recent years I have grown closer to my Aunt Sandy Pattan than I was in prior years. There was no particular reason we weren’t as close before, except that we were both busy. It is a poor excuse for not keeping in better contact with your aunt, and one that I’m glad has changed. It’s not that we necessarily get to see each other a whole lot more, but rather the quality of the conversations, and the visits have become much more precious to us. We have discovered a common interest in the family history, and a growing desire to get it documented for future generations, and that has solidified our…friendship really, because it is more than the typical aunt-niece relationship. When we talk, we share new discoveries that we have made, as well as the old ones, that we never seem to grow tired of hearing. We reminisce about the loved ones who have passed away, and shed some tears too, because we miss them so much, but talking about them, and even shedding the tears is what keeps their memories fresh in our hearts and minds.

In recent years I have grown closer to my Aunt Sandy Pattan than I was in prior years. There was no particular reason we weren’t as close before, except that we were both busy. It is a poor excuse for not keeping in better contact with your aunt, and one that I’m glad has changed. It’s not that we necessarily get to see each other a whole lot more, but rather the quality of the conversations, and the visits have become much more precious to us. We have discovered a common interest in the family history, and a growing desire to get it documented for future generations, and that has solidified our…friendship really, because it is more than the typical aunt-niece relationship. When we talk, we share new discoveries that we have made, as well as the old ones, that we never seem to grow tired of hearing. We reminisce about the loved ones who have passed away, and shed some tears too, because we miss them so much, but talking about them, and even shedding the tears is what keeps their memories fresh in our hearts and minds.

Aunt Sandy, being the youngest of nine children, had almost double the older siblings in some ways, because there were brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law who were a part of the family before she was a teenager, and some by the time she was two. As she said to me, “Those brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law were like my brothers and sisters, because they had been a part of the family for much of my memory.” That also gave her a unique perspective of the in-laws, because she got to see their playful side…the way they would be with her as a child. Of course, my uncles were playful with the nieces and nephews too, but it was different with her, because she was like their little sister. Those were some great times for young Aunt Sandy.

I was watching some of my parents’ old home movies last night, and there was Aunt Sandy a little girl of about  10 years. We were at a family picnic, because my parents and sister Cheryl were in Casper for a visit. They lived in Superior, Wisconsin then, and Cheryl was the only child they had then. The day was perfect, and everyone was having a great time. My parents, Allen and Collene Spencer had purchased a movie camera, and everyone was trying to decide if they wanted to be filmed or not. Most of the adults didn’t think they wanted to, but the kids were a little more open to the idea. I noticed that Aunt Sandy was having such a great time. There were more children to play with than usual for her, and everyone was having so much fun. She was literally jumping up and down with excitement. It was an awesome day for her. Today is Aunt Sandy’s birthday. Happy birthday Aunt Sandy!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

10 years. We were at a family picnic, because my parents and sister Cheryl were in Casper for a visit. They lived in Superior, Wisconsin then, and Cheryl was the only child they had then. The day was perfect, and everyone was having a great time. My parents, Allen and Collene Spencer had purchased a movie camera, and everyone was trying to decide if they wanted to be filmed or not. Most of the adults didn’t think they wanted to, but the kids were a little more open to the idea. I noticed that Aunt Sandy was having such a great time. There were more children to play with than usual for her, and everyone was having so much fun. She was literally jumping up and down with excitement. It was an awesome day for her. Today is Aunt Sandy’s birthday. Happy birthday Aunt Sandy!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Over the centuries, metals or the discovery of metals have been something that has created everything from excitement to violence. Probably the best known discovery was that of gold, and while it is very valuable, there are many other very important metals, like iron, for instance. Very seldom do we think about all the things that are made with iron, and what an inexpensive, yet versatile metal it is. Iron is one of the most abundant metals found on earth, making up close to five percent of its crust. These iron minerals are typically mixed with clay, sand, rock or gravel. Iron is so common that it may be found in your backyard. Nevertheless, it is only mined commercially when the concentration is large enough to make it worth going after. Iron is used in cookware, fencing, vehicles, motors, buildings, and steel, just to name a few. And, every American born will need 27,416 pounds of iron in their lifetime.

Over the centuries, metals or the discovery of metals have been something that has created everything from excitement to violence. Probably the best known discovery was that of gold, and while it is very valuable, there are many other very important metals, like iron, for instance. Very seldom do we think about all the things that are made with iron, and what an inexpensive, yet versatile metal it is. Iron is one of the most abundant metals found on earth, making up close to five percent of its crust. These iron minerals are typically mixed with clay, sand, rock or gravel. Iron is so common that it may be found in your backyard. Nevertheless, it is only mined commercially when the concentration is large enough to make it worth going after. Iron is used in cookware, fencing, vehicles, motors, buildings, and steel, just to name a few. And, every American born will need 27,416 pounds of iron in their lifetime.

On this day September 5, 1844, iron ore was discovered in Minnesota’s Mesabi Range. The discovery was made  while the miners were on their way to prospect for gold. Because gold was the metal everyone was excited about, the iron ore was virtually ignored. As metals go, the iron would become far more valuable in northern Minnesota than gold. In fact, for the past 50 years, Lake Superior iron ore accounts for 90% of United States iron ore production, with much of that ore coming from the Mesabi Range, where that first discovery occurred back in 1844. Iron ore makes up the majority of Lake Superior shipping, and would soon become the most lucrative occupation in the Lake Superior shipping industry. Just imagine if you were one of those men who walked away from the iron ore discovery, in search of gold, which most never found. Wouldn’t you be kicking yourself now? There were millions to be made in the iron industry.

while the miners were on their way to prospect for gold. Because gold was the metal everyone was excited about, the iron ore was virtually ignored. As metals go, the iron would become far more valuable in northern Minnesota than gold. In fact, for the past 50 years, Lake Superior iron ore accounts for 90% of United States iron ore production, with much of that ore coming from the Mesabi Range, where that first discovery occurred back in 1844. Iron ore makes up the majority of Lake Superior shipping, and would soon become the most lucrative occupation in the Lake Superior shipping industry. Just imagine if you were one of those men who walked away from the iron ore discovery, in search of gold, which most never found. Wouldn’t you be kicking yourself now? There were millions to be made in the iron industry.

Shipping on Lake Superior is dominated by iron ore cargo. Of course, that is not the only thing shipped, but the  iron ore ships, which are always called ore boats, are among the most amazing in my book. The largest ore boat, the Paul R. Tregurtha is the reigning “Queen of the Lakes” title holder as the longest vessel on the Great Lakes at 1,013 feet 6 inches was constructed in two sections. When my mom, Collene Spencer, my sister, Cheryl Masterson, and I were in Superior three years ago, we got to see this amazing vessel as it left port. Of all the ships on Lake Superior, the ore boats are the ones most people think of when they think of ships on the lake. For people who make their living on the lake, the ore boats are their bread and butter. And to think it all started with a discovery that no one seemed to care about. In the end, it was an unexpected gold mine.

iron ore ships, which are always called ore boats, are among the most amazing in my book. The largest ore boat, the Paul R. Tregurtha is the reigning “Queen of the Lakes” title holder as the longest vessel on the Great Lakes at 1,013 feet 6 inches was constructed in two sections. When my mom, Collene Spencer, my sister, Cheryl Masterson, and I were in Superior three years ago, we got to see this amazing vessel as it left port. Of all the ships on Lake Superior, the ore boats are the ones most people think of when they think of ships on the lake. For people who make their living on the lake, the ore boats are their bread and butter. And to think it all started with a discovery that no one seemed to care about. In the end, it was an unexpected gold mine.

Because I was born in Superior, Wisconsin, located at the tip of Lake Superior, and across the bridge from Duluth, Minnesota, I am interested in all things that have to do with that area. My family moved to Casper, Wyoming when I was three, so I was not raised in that area, but somehow, it is in my blood. I will always have roots I can feel there. We still have a large number of family members there, and we continue to get to know them more and more due to a trip back there, and continued connections on Facebook. For that family we are very grateful, because they are all amazing.

Because I was born in Superior, Wisconsin, located at the tip of Lake Superior, and across the bridge from Duluth, Minnesota, I am interested in all things that have to do with that area. My family moved to Casper, Wyoming when I was three, so I was not raised in that area, but somehow, it is in my blood. I will always have roots I can feel there. We still have a large number of family members there, and we continue to get to know them more and more due to a trip back there, and continued connections on Facebook. For that family we are very grateful, because they are all amazing.

As I said, I love the area around Lake Superior, and the shipping business that comes through there is an amazing thing to watch. In order for shipping to thrive on Lake Superior, they had to have a way to get the big oar boats and other large ships into the port. In 1892, a contest was held to find a solution for the transportation needs to go from Minnesota Point to the other side of the canal that was dug in 1871. a man named John Low Waddell came up with the winning design for a high rise vertical lift bridge. The city of Duluth was eager to build the bridge, but the War Department didn’t like the design, and so the project was cancelled before it started. It really was an unfortunate mistake.

Later, new plans were drawn up for a structure that would ferry people from one side to the other. This one was designed by Thomas McGilvray, a city engineer. That structure was finished in 1905. The gondola had a capacity of 60 tons and was able to carry 350 people, plus wagons, streetcars, and automobiles. The trip across took about a minutes and the ferry crossed once every five minutes, but as the population grew, the demand for a better way across grew too. They would have to rethink the situation, and amazingly, he firm finally commissioned with designing the new bridge was the descendant of Waddell’s company…the original design winner. The new design, which closely resembles the 1892 concept, is attributed to C.A.P. Turner. I guess they should have used that design in the first place, and it might have saved a lot of money.

Later, new plans were drawn up for a structure that would ferry people from one side to the other. This one was designed by Thomas McGilvray, a city engineer. That structure was finished in 1905. The gondola had a capacity of 60 tons and was able to carry 350 people, plus wagons, streetcars, and automobiles. The trip across took about a minutes and the ferry crossed once every five minutes, but as the population grew, the demand for a better way across grew too. They would have to rethink the situation, and amazingly, he firm finally commissioned with designing the new bridge was the descendant of Waddell’s company…the original design winner. The new design, which closely resembles the 1892 concept, is attributed to C.A.P. Turner. I guess they should have used that design in the first place, and it might have saved a lot of money.

Construction began in 1929. They knew that they had to be able to accommodate the tall ships that would pass through. In the new design, the roadway simply lifted in the middle, and after the ship went through it lowered  again, becoming a bridge for cars. The design is amazing, and grabs the attention of thousands of people on a regular basis. The new bridge first lifted for a vessel on March 29, 1930. Raising the bridge to its full height of 135 feet takes about a minute. The bridge is raised approximately 5,000 times per year. The bridge span is about 390 feet. As ships pass, there is a customary horn blowing sequence that is copied back. The bridge’s “horn” is actually made up of two Westinghouse Airbrake locomotive horns. Long-short-long-short means to raise the bridge, and Long-short-short is a friendly salute. The onlookers love it, and the crews often wave as well. It is like a parade of ships on a daily basis, and probably the reason that the bridge is so often the subject of pictures of the area. Happy 86th Anniversary to the Duluth Lift Bridge.

again, becoming a bridge for cars. The design is amazing, and grabs the attention of thousands of people on a regular basis. The new bridge first lifted for a vessel on March 29, 1930. Raising the bridge to its full height of 135 feet takes about a minute. The bridge is raised approximately 5,000 times per year. The bridge span is about 390 feet. As ships pass, there is a customary horn blowing sequence that is copied back. The bridge’s “horn” is actually made up of two Westinghouse Airbrake locomotive horns. Long-short-long-short means to raise the bridge, and Long-short-short is a friendly salute. The onlookers love it, and the crews often wave as well. It is like a parade of ships on a daily basis, and probably the reason that the bridge is so often the subject of pictures of the area. Happy 86th Anniversary to the Duluth Lift Bridge.

When I think of my grandmother, Harriet “Hattie” Byer, the person that comes to mind is Grandma as she was in my adult years. f course, by that time, she was a great grandmother many times over, and so had aged into the kind of grandma you always see on television…gray hair and somewhat wrinkled. In reality, it is television’s view of what a grandmother should look like that is warped in many cases…odd since they try very hard to make everyone else forever ageless. It’s not that I don’t remember the Grandma of my youth, it’s just that I really don’t think of her that way. That wasn’t what she was like as she aged, and I was at an age to place a specific memory of her in my memory files. Nevertheless, when it came to being the boss, the kidder, or the disciplinarian, all I can say is, don’t let her looks or her small stature fool you, because Grandma was in charge, and that’s all there is to it. Just ask anyone of her kids, grandkids, or

When I think of my grandmother, Harriet “Hattie” Byer, the person that comes to mind is Grandma as she was in my adult years. f course, by that time, she was a great grandmother many times over, and so had aged into the kind of grandma you always see on television…gray hair and somewhat wrinkled. In reality, it is television’s view of what a grandmother should look like that is warped in many cases…odd since they try very hard to make everyone else forever ageless. It’s not that I don’t remember the Grandma of my youth, it’s just that I really don’t think of her that way. That wasn’t what she was like as she aged, and I was at an age to place a specific memory of her in my memory files. Nevertheless, when it came to being the boss, the kidder, or the disciplinarian, all I can say is, don’t let her looks or her small stature fool you, because Grandma was in charge, and that’s all there is to it. Just ask anyone of her kids, grandkids, or  great grandkids, who might have had the misfortune of cross her. Most of us were done crossing Grandma, but there were some who were brave enough to try again…if you call that bravery. There might be a different word for it, in reality.

great grandkids, who might have had the misfortune of cross her. Most of us were done crossing Grandma, but there were some who were brave enough to try again…if you call that bravery. There might be a different word for it, in reality.

When I was little, my family lived in Superior, Wisconsin. That made it hard for her to see my sister, Cheryl Masterson and me when we were little. Grandma and Grandpa did make trips up to see us, and really loved it. Mom and Dad showed them around the area, and they spent time with us too. I don’t remember those visits, but my guess is that my sister, Cheryl does, because she was a couple of years older than I was. I love looking at the pictures of those visits with my grandparents. They are precious to me now, because of course, my parents, Grandpa, and Grandma are in Heaven now. Looking back at those moments by the lake, at the house, and on trips we took, are such wonderful memories.

We moved back to Casper before I turned three, and then we had chances to see them more often. I remember those many visits to their house so well. I can’t say I was one of those kids who learned from her mistakes, but I don’t remember very many times that I was on the wrong side of Grandma. You might call me chicken…and you would be right…either that, or smart. When Grandma spanked, it hurt. Thankfully I outgrew those days, and in the end, I remember my sweet grandma as a little old lady with gray hair. Nevertheless, she was mine, and my sisters and cousins…and we loved her. Today would have been Grandma Byer’s 107th birthday, if she were still with us. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandma. We love and miss you very much.

A couple of years ago, my mom, Collene Spencer, my sister, Cheryl Masterson, and I made a trip back to Superior, Wisconsin and Duluth, Minnesota to reconnect, and meet family members there. We had a wonderful trip, and both my sister and I have found sites on Facebook that display pictures of the area. Cheryl and I were both born in Superior, Wisconsin, so we feel a closeness to the area, even though we have not lived there for many years. It is still the area of our roots. Now that we have been back in a more recent time, a continue to feel drawn to the area. The strange thing is that the things I am interested in at this time, are more historic things…some of them, things that no longer exist. In my memory, we didn’t spend a lot of time in Duluth, but I’m probably mistaken on that count…at least to a degree. Superior, Wisconsin and Duluth, Minnesota are so close to each other, that if there were no signs to tell you so, you might not realize that you have left one and entered the other. I’m sure my parents shopped in Duluth, simply because as the larger of the two cities, there was quite likely more variety there.

A couple of years ago, my mom, Collene Spencer, my sister, Cheryl Masterson, and I made a trip back to Superior, Wisconsin and Duluth, Minnesota to reconnect, and meet family members there. We had a wonderful trip, and both my sister and I have found sites on Facebook that display pictures of the area. Cheryl and I were both born in Superior, Wisconsin, so we feel a closeness to the area, even though we have not lived there for many years. It is still the area of our roots. Now that we have been back in a more recent time, a continue to feel drawn to the area. The strange thing is that the things I am interested in at this time, are more historic things…some of them, things that no longer exist. In my memory, we didn’t spend a lot of time in Duluth, but I’m probably mistaken on that count…at least to a degree. Superior, Wisconsin and Duluth, Minnesota are so close to each other, that if there were no signs to tell you so, you might not realize that you have left one and entered the other. I’m sure my parents shopped in Duluth, simply because as the larger of the two cities, there was quite likely more variety there.

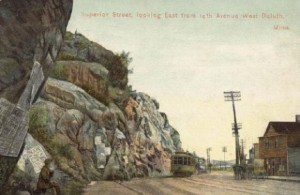

Recently, I started looking into some of the history of that general area, and stumbled on something  interesting. Duluth had an incline railway. Personally, I like incline railways, but I have never seen one that was in a city. Incline railways seem more like something that you would see at a tourist attractions, than anything that you would use in everyday life. Nevertheless, Duluth, in 1891, had a streetcar line, and in December 1891, the Duluth Street Railway Company opened the incline railway, as part of that street car line. The Incline Railway was on the right-of-way of Seventh Avenue West. The Duluth Street Railway Company had received a charter from the state in 1881 to build a streetcar line for Duluth. The hillside on Seventh Avenue West was too steep for a regular rail line, so they built an incline railway for that area. From it’s base station on Superior Street, the Incline climbed 509 feet in slightly more than half a mile, on a ten foot gauge track. Originally, a pair of forty one by fifteen foot cars counterbalanced each other, one going up while the other one descended. They were built to accommodate four teams and wagons, or up to 250 standing passengers. The Incline was powered by a stationary steam engine at the top. The trip took sixteen minutes, one way…just enough time to make it an enjoyable trip.

interesting. Duluth had an incline railway. Personally, I like incline railways, but I have never seen one that was in a city. Incline railways seem more like something that you would see at a tourist attractions, than anything that you would use in everyday life. Nevertheless, Duluth, in 1891, had a streetcar line, and in December 1891, the Duluth Street Railway Company opened the incline railway, as part of that street car line. The Incline Railway was on the right-of-way of Seventh Avenue West. The Duluth Street Railway Company had received a charter from the state in 1881 to build a streetcar line for Duluth. The hillside on Seventh Avenue West was too steep for a regular rail line, so they built an incline railway for that area. From it’s base station on Superior Street, the Incline climbed 509 feet in slightly more than half a mile, on a ten foot gauge track. Originally, a pair of forty one by fifteen foot cars counterbalanced each other, one going up while the other one descended. They were built to accommodate four teams and wagons, or up to 250 standing passengers. The Incline was powered by a stationary steam engine at the top. The trip took sixteen minutes, one way…just enough time to make it an enjoyable trip.

In 1925, it was noted that the Incline carried an average of 2,170 weekday passengers, while the connecting  Highland streetcar line carried an average of only 1,114 weekday passengers. I’m sure that was because people like incline railways…they are unique….besides, climbing that hill would not be fun. Hourly checks showed that most riders traveled downhill in the morning rush hour and uphill during the afternoon rush hour. Most likely they were commuting to and from work. The Duluth Incline Railway was never profitable. Nevertheless, it and the Highland line were the last remnants of the streetcar system to be replaced by buses. Their last day of service was September 4, 1939. For that reason, I’m sure that many of the current residents of Duluth don’t even know about the incline railroad. I didn’t either, until I stumbled on it.

Highland streetcar line carried an average of only 1,114 weekday passengers. I’m sure that was because people like incline railways…they are unique….besides, climbing that hill would not be fun. Hourly checks showed that most riders traveled downhill in the morning rush hour and uphill during the afternoon rush hour. Most likely they were commuting to and from work. The Duluth Incline Railway was never profitable. Nevertheless, it and the Highland line were the last remnants of the streetcar system to be replaced by buses. Their last day of service was September 4, 1939. For that reason, I’m sure that many of the current residents of Duluth don’t even know about the incline railroad. I didn’t either, until I stumbled on it.

Wherever there is snow, you can bet there will be a snowman. Maybe not in every yard, but in many of them. I’m not sure who first has the idea to make a snowman, but once it got started, it caught on quickly. Now it is simply a winter tradition, and if the littlest ones are too little, their parents will build it fir them or assist in building it if need be.

Wherever there is snow, you can bet there will be a snowman. Maybe not in every yard, but in many of them. I’m not sure who first has the idea to make a snowman, but once it got started, it caught on quickly. Now it is simply a winter tradition, and if the littlest ones are too little, their parents will build it fir them or assist in building it if need be.

The building of the first snowman is unknown, but Bob Eckstein, author of The History of the Snowman documented snowmen back to medieval times. He researched paintings in European museums, art galleries, and libraries. The earliest documentation he found was a marginal illustration from a work titled Book of Hours from 1380, found in Koninklijke Bibliotheek, in The Hague. Who knew that snowmen went back that far.

When it comes to the tallest snowman, we would have to clarify the 122 feet 1 inch snowman, was actually a snow woman. She was built in 2008 in Bethel, Maine, and was named in honor of Olympia Snowe, a United States Senator representing the state of Maine. In 2015, a man from the Wisconsin was noted for making a large snowman 22 feet tall and with a base 12 feet wide. Still, the average snowman stands between three and six feet tall, because that is the height that the average builder takes the time to do. There are several ways to build a snowman, and in fact the styles can be very creative, or total disasters, depending on the abilities of the builder. Some people are even snowman artists. Their snowmen look like actual sculptures.

As kids, my sisters and I have built more snowmen than we can count. Some turned out great and others, not so much. I don’t recall seeing a lot of pictures of our snowmen, but we came across one of my sister, Cheryl Masterson building one that I’m sure our dad must have helped with. I suppose that milestones like building your first snowman didn’t exactly fall into place the same category as those first steps or high school graduation, but it is still a first. Unfortunately, like most of the lesser firsts, there isn’t usually as much documentation as the subsequent children come along. Or it could be that little firsts like snowmen just don’t seem all that important when you have multiple children. They are just another winter tradition.

During this journey to find my ancestors and my living family, there have been several times that I have felt that I had made a rare find. Of course, how could it be rare if there were several times, you might be thinking. I thought the same thing, and yet, some of the people I have come across have become so special to me that they could only be classified as a rare find. People like my father-in-law’s half brother, Butch Schulenberg, and our cousins Paul and Betty Noyes, come to mind immediately. But then, I also think of Tracey Inglimo, Denny Fredrick, Tim and Shawn Fredrick, Shirley Cameron, Pam and Mike Wendling, Bill and Maureen Spencer, and the many Schumacher cousins in

During this journey to find my ancestors and my living family, there have been several times that I have felt that I had made a rare find. Of course, how could it be rare if there were several times, you might be thinking. I thought the same thing, and yet, some of the people I have come across have become so special to me that they could only be classified as a rare find. People like my father-in-law’s half brother, Butch Schulenberg, and our cousins Paul and Betty Noyes, come to mind immediately. But then, I also think of Tracey Inglimo, Denny Fredrick, Tim and Shawn Fredrick, Shirley Cameron, Pam and Mike Wendling, Bill and Maureen Spencer, and the many Schumacher cousins in

Wisconsin and Minnesota. I think of Nick and Laura Weber, and Joe Weber. As I think of these people, new rare finds and renewed rare finds, I begin to realize that as I have discovered these special people, some I have never met in person, and some that I have known all my life, but lost track of, I begin to realize that maybe rare finds in the family line aren’t really as rare as I thought they were after all.

Wisconsin and Minnesota. I think of Nick and Laura Weber, and Joe Weber. As I think of these people, new rare finds and renewed rare finds, I begin to realize that as I have discovered these special people, some I have never met in person, and some that I have known all my life, but lost track of, I begin to realize that maybe rare finds in the family line aren’t really as rare as I thought they were after all.

I have been thinking about what it is that makes a person a rare find, and the thing that immediately comes to mind is that these people truly care about me…about what I think and who I am. I find that these people are kindred spirits…something I had not really given much thought to until I got into the “Anne of Green Gables”

movies, but after watching those movies, I realize just how important kindred spirits really are. Kindred spirits share the same values, goals, and desires, even if they are is slightly different ways. I think it is the values though that mean the most. Maybe that is a big part of what makes these people a rare find. So much has changed in our world these days, and while we all have maybe a slightly different view of what things are wrong and how to fix them, I still find that these people are value driven people…patriots, who love this country and what it stands for.

movies, but after watching those movies, I realize just how important kindred spirits really are. Kindred spirits share the same values, goals, and desires, even if they are is slightly different ways. I think it is the values though that mean the most. Maybe that is a big part of what makes these people a rare find. So much has changed in our world these days, and while we all have maybe a slightly different view of what things are wrong and how to fix them, I still find that these people are value driven people…patriots, who love this country and what it stands for.

The longer I think about it, the more I realize that while finding people who compliment who I am is not such a rare find, it is still a

rare find that there are so many people who have become so very special to me. It warms my heart to think of these people, and it warms my heart with every conversation I have with them. It is my hope to someday meet those precious people who I have never had the pleasure of meeting in person. I know we will really hit it off, because we are family and kindred spirits. It’s a great combination. While my “rare finds” have not really been so rare after all, I am so blessed by each and every one of then, and that makes them absolutely priceless. I am very blessed to know them all.

rare find that there are so many people who have become so very special to me. It warms my heart to think of these people, and it warms my heart with every conversation I have with them. It is my hope to someday meet those precious people who I have never had the pleasure of meeting in person. I know we will really hit it off, because we are family and kindred spirits. It’s a great combination. While my “rare finds” have not really been so rare after all, I am so blessed by each and every one of then, and that makes them absolutely priceless. I am very blessed to know them all.

There comes a point after your parent passes away, when you find yourself wanting to pick up the phone and call them, just to ask them a question. It can be anything from family history, to life advise, to simply wanting to share the good times with them. Suddenly, you speak their name as if they are still here, and then, just as suddenly, you realize that they aren’t. That is the place I have found myself several times. Driving by Mom’s house, I thought of her. When exciting things have happened, I’ve thought of calling her. When I had a family question, that she could answer easily, I missed her terribly. And then there were the times I mentioned talking to her in a conversation, only to stop suddenly, shocked about what I had just said. I knew she was gone, but my mind just hadn’t accepted it, I guess.

There comes a point after your parent passes away, when you find yourself wanting to pick up the phone and call them, just to ask them a question. It can be anything from family history, to life advise, to simply wanting to share the good times with them. Suddenly, you speak their name as if they are still here, and then, just as suddenly, you realize that they aren’t. That is the place I have found myself several times. Driving by Mom’s house, I thought of her. When exciting things have happened, I’ve thought of calling her. When I had a family question, that she could answer easily, I missed her terribly. And then there were the times I mentioned talking to her in a conversation, only to stop suddenly, shocked about what I had just said. I knew she was gone, but my mind just hadn’t accepted it, I guess.

It seems like after a loss, you find yourself always looking back on the past…missing the person that is gone. It isn’t about wondering if my mom is ok, because I know exactly where she is and I know she is happy in Heaven. It’s just that with both of my parents, there is so much more that I wanted to talk to them about. There were questions I wish I had asked. Now it’s too late.

My favorite part about looking through my parents things, has been the pictures we have found. Those pictures tell a story that we had never known to ask about. It has made a way for us to see the past and some of what it was like even though we couldn’t ask about it. I guess that is some consolation. The undeveloped film we found has been such a surprise treasure. Seeing our parents when they were young and us as kids has been amazing. Yes, we lived those moments, but now we can re-live those moments. We can see a little bit about our parents personalities from the pictures. We get to see the things they liked to do, and the places they liked to go. I have really enjoyed seeing that young side of them. My sister, Cheryl Masterson and I wondered what it would’ve been like had we stayed in Superior, Wisconsin. For me, the pictures have given us a glimpse of what life was like there. These were things that we would have asked our parents, but never had the chance.

When your parents have passed away, you find so many things that you wish you had talked to them about. There are so many stories about the past, that you can never ask about now. The problem is that you didn’t know that you should ask when you were younger. We are not alone and finding this out after their passing, because I think a lot of kids find it out this way. Today marks the eighth month since my mom, Collene Spencer went to Heaven, and every day brings to mind a question I would ask her…if only I could.