walla walla

When Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and their family contracted the measles in 1847, little did they know that it would not be measles that would endanger their lives, but the treatment given after they got over the measles. The Whitmans were American missionaries who lived and worked in the area of what is now Walla Walla, Washington. When the measles broke out, the missionaries managed to survive the disease, most likely by using normal medical protocols, but the Cayuse Indians, who lived in the area, and weren’t known for cleanliness, did not fare so well. Of course, there is no proof that it was a lack of cleanliness that caused the deaths, nor was there proof that it did not. The main reason that the Whitman Mission was included in the ensuing massacre is that the Cayuse came to them for help, and lives were lost.

When Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and their family contracted the measles in 1847, little did they know that it would not be measles that would endanger their lives, but the treatment given after they got over the measles. The Whitmans were American missionaries who lived and worked in the area of what is now Walla Walla, Washington. When the measles broke out, the missionaries managed to survive the disease, most likely by using normal medical protocols, but the Cayuse Indians, who lived in the area, and weren’t known for cleanliness, did not fare so well. Of course, there is no proof that it was a lack of cleanliness that caused the deaths, nor was there proof that it did not. The main reason that the Whitman Mission was included in the ensuing massacre is that the Cayuse came to them for help, and lives were lost.

The Whitman massacre, which was also known as the Whitman killings and the Tragedy at Waiilatpu, mostly refers to the killing of American missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, and eleven others who were involved with the mission, on November 29, 1847. The missionaries were killed by a small group of Cayuse men who accused Whitman of poisoning 200 Cayuse in his medical care during an outbreak of measles that included the Whitman household. The massacre occurred at the Whitman Mission at the junction of the Walla Walla River and Mill Creek in what is now southeastern Washington near Walla Walla. That massacre changed everything in the history of the Pacific Northwest…at least as far as the Oregon Territory was concerned anyway. The massacre caused the United States Congress to take action declaring the territorial status of the Oregon Country, thereby establishing the Oregon Territory on August 14, 1848, to protect the white settlers.

The Cayuse justified the killings by saying that any time a “medicine man” failed to bring about healing to a patient, the medicine man was killed for giving out “bad medicine” to his patients. Basically, the “medicine man” who officiated over a terminal patient, had better plan on going with the patient, because any death was going to be his fault. Basically, the Cayuse looked at Whitman’s failure to cure the Cayuse people as a criminal inability to perform his duties as “medicine man.” Of course, their “findings” were not logical, but they weren’t  thinking logically and didn’t really care anyway. The warriors were simply acting out of grief and an expectation of revenge for what they believed was a serious injustice against their people. In the White Man’s language, the massacre is usually ascribed to “the inability of Whitman, a physician, to prevent the measles outbreak.” At least three Cayuse villages held Whitman responsible for the widespread epidemic that killed those hundreds of Cayuse people, while leaving the White settlers comparatively unscathed. Some Cayuse people even accused the settlers of poisoning the Cayuse as part of a plan to take their land. Of course, justice needed to be carried out, and in the trial of five Cayuse warriors accused of the killing, the Cayuse used for their defense that it was tribal law to kill the medicine man who gives bad medicine.

thinking logically and didn’t really care anyway. The warriors were simply acting out of grief and an expectation of revenge for what they believed was a serious injustice against their people. In the White Man’s language, the massacre is usually ascribed to “the inability of Whitman, a physician, to prevent the measles outbreak.” At least three Cayuse villages held Whitman responsible for the widespread epidemic that killed those hundreds of Cayuse people, while leaving the White settlers comparatively unscathed. Some Cayuse people even accused the settlers of poisoning the Cayuse as part of a plan to take their land. Of course, justice needed to be carried out, and in the trial of five Cayuse warriors accused of the killing, the Cayuse used for their defense that it was tribal law to kill the medicine man who gives bad medicine.

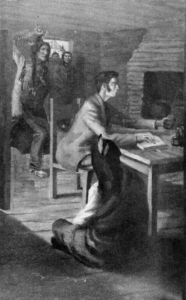

Everything blew up on November 29, 1847, when Tiloukaikt, Tomahas, Kiamsumpkin, Iaiachalakis, Endoklamin, and Klokomas, who were enraged by Joe Lewis’ talk, attacked Waiilatpu. According to Mary Ann Bridger, the young daughter of mountain man Jim Bridger, who was a lodger of the mission and eyewitness to the event, the men knocked on the Whitmans’ kitchen door and demanded medicine. Bridger went on to say that “Marcus brought the medicine and began a conversation with Tiloukaikt. While Whitman was distracted, Tomahas struck him twice in the head with a hatchet from behind and another man shot him in the neck. The Cayuse men rushed outside and attacked the white men and boys working outdoors.” Whitman’s wife, Narcissa found him fatally wounded, and while he lived for several hours after the attack, and sometimes responded to her anxious reassurances, he later died of his injuries. Catherine Sager, who had been with Narcissa in another room when the attack occurred, later wrote in her reminiscences that “Tiloukaikt chopped the doctor’s face so badly that his features could not be recognized.”

Had she stayed hidden, Narcissa might have lived through the attack, but she later went to the door to look out and was immediately shot by a Cayuse man. Then she was coaxed out of the house. She died from a volley of

gunshots immediately upon leaving the house. The rest of the people killed in the massacre were Andrew Rodgers, Jacob Hoffman, LW Saunders, Walter Marsh, John and Francis Sager, Nathan Kimball, Isaac Gilliland, James Young, Crocket Bewley, and Amos Sales. A carpenter who had been working on the house, Peter Hall managed to escape the massacre and reach Fort Walla Walla to raise the alarm and get help. After leaving Fort Walla Walla, he left to warn Fort Vancouver, but he never made it. Sone think that Hall drowned in the Columbia River, while others speculate that he was caught and killed. On man, Chief “Beardy” tried to stop the massacre, but it was too out of control. The warriors were insanely crazy with grief, and nothing was going to stop their revenge. Chief “Beardy” was found crying while riding toward the Whitman Mission.

gunshots immediately upon leaving the house. The rest of the people killed in the massacre were Andrew Rodgers, Jacob Hoffman, LW Saunders, Walter Marsh, John and Francis Sager, Nathan Kimball, Isaac Gilliland, James Young, Crocket Bewley, and Amos Sales. A carpenter who had been working on the house, Peter Hall managed to escape the massacre and reach Fort Walla Walla to raise the alarm and get help. After leaving Fort Walla Walla, he left to warn Fort Vancouver, but he never made it. Sone think that Hall drowned in the Columbia River, while others speculate that he was caught and killed. On man, Chief “Beardy” tried to stop the massacre, but it was too out of control. The warriors were insanely crazy with grief, and nothing was going to stop their revenge. Chief “Beardy” was found crying while riding toward the Whitman Mission.

The United States Navy ship USS Knox (FF-1052) was named for Commodore Dudley Wright Knox, who was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War and World War I. Born in Fort Walla Walla, Washington, on June 21, 1877, Knox was also a prominent naval historian. For many years he oversaw the Navy Department’s historical office, now called the Naval Historical Center. I can’t say for sure, nor exactly how, but I suspect that Dudley Wright Knox is somehow related to my husband, Bob Schulenberg’s Knox side of the family. That will be a subject I will need to explore further in the future.

The United States Navy ship USS Knox (FF-1052) was named for Commodore Dudley Wright Knox, who was an officer in the United States Navy during the Spanish-American War and World War I. Born in Fort Walla Walla, Washington, on June 21, 1877, Knox was also a prominent naval historian. For many years he oversaw the Navy Department’s historical office, now called the Naval Historical Center. I can’t say for sure, nor exactly how, but I suspect that Dudley Wright Knox is somehow related to my husband, Bob Schulenberg’s Knox side of the family. That will be a subject I will need to explore further in the future.

Knox attended school in Washington DC and graduated from the United States Naval Academy on June 5, 1896. Following his graduation, he served in the Spanish-American War aboard the screw steamer Maple in Cuban waters. A screw steamer or screw steamship is an old term for a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine, using one or more propellers…also known as screws…to propel it through the water. These ships were nicknamed iron screw steam ship.

His was a long and distinguished career. During the Philippine-American War, Knox commanded the gunboat Albay, and during the Chinese Boxer Rebellion, the gunboat Iris. He then commanded three of the Navy’s first destroyers…Shubrick, Wilkes, and Decatur. Following his attendance and graduation from the Naval War College in 1912–13, Knox became the aide to Captain William Sims, commanding the Atlantic Torpedo Flotilla. During the cruise of the “Great White Fleet,” he was sent around the world by President Theodore Roosevelt, as an ordnance officer on the battleship Nebraska (BB-14).

He took the lead in developing naval operational doctrine when he published an article of great influence in the US Naval Institute Proceedings in 1915. He was Fleet Ordnance Officer in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, serving in the Office of Naval Intelligence, and commanding the Guantanamo Bay Naval Station. The job of a Fleet Ordnance Officers is to ensure that weapons systems, vehicles, and equipment are ready and available…and in perfect working order, at all times. These officers also manage the developing, testing, fielding, handling, storage, and disposal of munitions. In November 1917, Knox joined the staff of, by then, Admiral William Sims, Commander of US Naval Forces in European Waters. Knox earned the Navy Cross for “distinguished service” while serving as Aide in the Planning Section and later in the Historical Section. He was promoted to Captain on  February 1, 1918. In March 1919, Knox returned to the United States. He served for a year on the faculty of the Naval War College, where he was a key figure on the Knox-King-Pye Board that examined professional military education. In 1920–21, he commanded the armored cruiser Brooklyn (ACR-3), then the protected cruiser Charleston (C-22) before resuming duty in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

February 1, 1918. In March 1919, Knox returned to the United States. He served for a year on the faculty of the Naval War College, where he was a key figure on the Knox-King-Pye Board that examined professional military education. In 1920–21, he commanded the armored cruiser Brooklyn (ACR-3), then the protected cruiser Charleston (C-22) before resuming duty in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

Also in 1920, Knox first began his work as a naval publicist, serving as naval editor of the Army and Navy Journal until 1923. He then became the naval correspondent of the Baltimore Sun in 1924 – 1946, and naval correspondent of the New York Herald Tribune in 1929. While he was transferred to the Retired List of the Navy on October 20, 1921, he actually and strangely continued on active duty, serving simultaneously as Officer in Charge, Office of Naval Records and Library, and as Curator for the Navy Department. Knox played a key role in creating the Naval Historical Foundation. Early in World War II, he was assigned additional duty as Deputy Director of Naval History.

In a career that spanned half of a century, Knox’s leadership inspired diligence, efficiency, and initiative while he guided, improved, and expanded the Navy’s archival and historical operations. Knox had personal connections to President Roosevelt, Fleet Admiral Ernest J King, and other senior leaders in the Navy Department. These relationships allowed him to play an instrumental role, albeit behind the scenes in the years leading up to and during World War II.

Knox published a number of writings and several books…including his first book “The Eclipse of American Sea Power” (1922) and “A History of the United States Navy” (1936). “A History of the United States Navy” is recognized as “the best one-volume history of the United States Navy in existence.” Through his personal connection with President Roosevelt, he was able to publish key, multi-volume collections of documents on  naval operations in The Quasi-War with France in 1798–1800, the first Barbary war and the second Barbary War…stories that may not have been told, had he not taken the initiative.

naval operations in The Quasi-War with France in 1798–1800, the first Barbary war and the second Barbary War…stories that may not have been told, had he not taken the initiative.

November 2, 1945, found Knox promoted to Commodore, and awarded the Legion of Merit for “exceptionally meritorious conduct” while directing the correlation and preservation of accurate records of the US naval operations in World War II, thus protecting this vital information for posterity. Finally, on June 26, 1946, Knox was relieved of all active-duty work. He died in Bethesda, Maryland, on June 11, 1960. His cause of death is listed as unknown. He was 83 years old.

The old West was a rugged, unforgiving place, and for a long time it was thought to be a man’s place, and completely unsafe for women. Men went west, mined for gold, and came home to their families. A man would have to be insane to bring his wife and children to the West. Nevertheless, it was really only a matter of time before someone decided that the west was going to be settled, and it was going to take both men and women to settle the West…otherwise it was always going to be a job site and not a home. Someone had to make the first move, and I can imagine how the parents of those first women must have felt when their daughters told them they were moving out west. It must have been like thinking, “who was this idiot their daughter has married!” Of course, women had come as far as the Rocky Mountains, so going further wasn’t that strange, but it was still the unknown.

The old West was a rugged, unforgiving place, and for a long time it was thought to be a man’s place, and completely unsafe for women. Men went west, mined for gold, and came home to their families. A man would have to be insane to bring his wife and children to the West. Nevertheless, it was really only a matter of time before someone decided that the west was going to be settled, and it was going to take both men and women to settle the West…otherwise it was always going to be a job site and not a home. Someone had to make the first move, and I can imagine how the parents of those first women must have felt when their daughters told them they were moving out west. It must have been like thinking, “who was this idiot their daughter has married!” Of course, women had come as far as the Rocky Mountains, so going further wasn’t that strange, but it was still the unknown.

On this day in 1836, Narcissa Whitman arrived in Walla Walla, Washington, becoming one of the first Anglo women to settle west of the Rocky Mountains. Narcissa and Marcus Whitman, along with their close friends Eliza and Henry Spalding, had departed from New York earlier that year on the long overland journey to the far western edge of the continent. These days, that trip can be  made in a matter of hours, but in those days, it took lots of planning and months to accomplish such a trip. The two couples were missionaries, and Narcissa wrote that they were determined to convert the “benighted ones” living in “the thick darkness of heathenism” to Christianity. I guess there was no specific word for Indians, or Native Americans back then, or she just liked her version better. Mission work was one of the big reasons for heading west…besides land, and gold, of course.

made in a matter of hours, but in those days, it took lots of planning and months to accomplish such a trip. The two couples were missionaries, and Narcissa wrote that they were determined to convert the “benighted ones” living in “the thick darkness of heathenism” to Christianity. I guess there was no specific word for Indians, or Native Americans back then, or she just liked her version better. Mission work was one of the big reasons for heading west…besides land, and gold, of course.

That summer when they crossed the continental divide at South Pass, Narcissa and Eliza became the first Anglo-American women in history to travel west of the Rocky Mountains. I suppose it was like going to another planet to the women, who went with no real idea of what they would be facing in the new frontier. Toward the end of their difficult 1,800 mile journey, the two couples split up, with the Spaldings heading for Idaho while  Narcissa and her husband traveled to a settlement near present-day Walla Walla, Washington, where they established a mission for the Cayuse Indians. I can only imagine how the two women must have felt, knowing that it would be a very long time before they had the company of another Anglo woman. For 11 years the couples’ missionary work went well, and they succeeded in converting many of the Cayuse to Christianity. Then in 1847, a devastating measles epidemic swept through the area, killing many of the Cayuse, who had no immunity to the disease, while leaving most of the white people at the mission suspiciously unharmed. Convinced that the missionaries or their god had cursed them with an evil plague, a band of the Cayuse Indians attacked the mission and killed 14 people, including Narcissa and her husband on November 29, 1847. Narcissa Whitman thus became not only one of the first white women to live in the Far West, but also one of the first white women to die there too. She was just 39 years old at the time she was murdered.

Narcissa and her husband traveled to a settlement near present-day Walla Walla, Washington, where they established a mission for the Cayuse Indians. I can only imagine how the two women must have felt, knowing that it would be a very long time before they had the company of another Anglo woman. For 11 years the couples’ missionary work went well, and they succeeded in converting many of the Cayuse to Christianity. Then in 1847, a devastating measles epidemic swept through the area, killing many of the Cayuse, who had no immunity to the disease, while leaving most of the white people at the mission suspiciously unharmed. Convinced that the missionaries or their god had cursed them with an evil plague, a band of the Cayuse Indians attacked the mission and killed 14 people, including Narcissa and her husband on November 29, 1847. Narcissa Whitman thus became not only one of the first white women to live in the Far West, but also one of the first white women to die there too. She was just 39 years old at the time she was murdered.