United States

As the United States was being settled, a number of wars were fought between the Native Americans and the White Man. So much anger and so many hard feelings had passed between the two groups that it seemed like peace could never be achieved. Finally, in an attempt to convince local Native Americans to make peace with the United States, the Jesuit missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet met with the Sioux leader Sitting Bull in what is present-day Montana. He saw an urgent need to make peace and decided to go for it.

As the United States was being settled, a number of wars were fought between the Native Americans and the White Man. So much anger and so many hard feelings had passed between the two groups that it seemed like peace could never be achieved. Finally, in an attempt to convince local Native Americans to make peace with the United States, the Jesuit missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet met with the Sioux leader Sitting Bull in what is present-day Montana. He saw an urgent need to make peace and decided to go for it.

De Smet was a native of Belgium, who came to the United States in 1821 at the age of 20. Once in the states, he became a novice of the Jesuit order in Maryland. De Smet was ordained in Saint Louis, and as a priest, decided to be a missionary to the Native Americans of the Far West. It was an ambitious goal, but in 1838, he was sent to evangelize the Potawatomi villages near present-day Council Bluffs, Iowa. De Smet met a delegation of Flathead Indians there. The Indians had come east looking for a “black robe” whom they hoped might be able to aid their tribe. Of course, a “black robe” would be a priest, and since De Smet was indeed a priest, they had found what they were looking for. De Smet worked with the Flathead Indians several times during the 1840s in present-day western Montana. While there, he established a mission and actually secured a peace treaty with the Blackfeet, who had previously been the irreconcilable enemy of the Flathead.

His hard work earned De Smet a reputation as a white man who could be trusted to negotiate disputes between Native Americans and the US government, which was not something that very many people could boast. The disputes between the Indians and the US government became fairly commonplace in the West during the 1860s. The Plains Indians, like the Sioux and Cheyenne resisted the growing flood of white settlers invading their territories and killing their game animals. As the conflicts continued, the US government began to demand  that all the Plains Indians be relocated to reservations, another source of contention. The leaders in the American government and military had hoped that the relocation could be achieved through negotiations, but in the absence of a peaceful relocation, they were perfectly willing to use violence to force the local Native Americans to comply. It was futile to fight the change, but anyone can see why the Native Americans would try. They didn’t want to be forced to stay in just one area and to be told what they could and could not do…and in reality, the reservations have not proven to be the best thing for either side. Nevertheless, that is where we are today, and in many ways, the situation hasn’t improved much, except there aren’t Indian wars, so I guess that is a good thing. The disputes are handled differently now, but the feeling of a nation inside a nation is one that really isn’t perfect. Still, the Indian Nation does exist inside the United States, and they do have jurisdiction in their own territory, and I don’t suppose the feeling of separation will ever change.

that all the Plains Indians be relocated to reservations, another source of contention. The leaders in the American government and military had hoped that the relocation could be achieved through negotiations, but in the absence of a peaceful relocation, they were perfectly willing to use violence to force the local Native Americans to comply. It was futile to fight the change, but anyone can see why the Native Americans would try. They didn’t want to be forced to stay in just one area and to be told what they could and could not do…and in reality, the reservations have not proven to be the best thing for either side. Nevertheless, that is where we are today, and in many ways, the situation hasn’t improved much, except there aren’t Indian wars, so I guess that is a good thing. The disputes are handled differently now, but the feeling of a nation inside a nation is one that really isn’t perfect. Still, the Indian Nation does exist inside the United States, and they do have jurisdiction in their own territory, and I don’t suppose the feeling of separation will ever change.

The first official space flight occurred on April 12, 1961, when Soviet astronaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who, aboard the first successful crewed spaceflight, became the first human to journey into outer space. Traveling on Vostok 1, Gagarin completed one orbit of Earth on 12 April 1961. While that was the first official manned space flight, there were other times that man touched space.

The first official space flight occurred on April 12, 1961, when Soviet astronaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who, aboard the first successful crewed spaceflight, became the first human to journey into outer space. Traveling on Vostok 1, Gagarin completed one orbit of Earth on 12 April 1961. While that was the first official manned space flight, there were other times that man touched space.

The North American X-15 was an experimental US single seat rocket powered airplane that was taken aloft by a B-52 bomber acting as its “mother ship” and released to test extremely high speed and extremely high-altitude flight. The first such flight took place on June 8, 1959.

The hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft known as the North American X-15, was operated by the United States Air Force and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration as part of the X-plane series of experimental aircraft. While it didn’t exactly go into space, the X-15 set speed and altitude records in the 1960s, reaching the edge of outer space and returning with valuable data used in aircraft and spacecraft design, making it a precursor to the spacecraft of today. The X-15’s highest speed, 4,520 miles per hour , was achieved on October 3, 1967, when William J Knight flew at Mach 6.7 at an altitude of 102,100 feet or 19.34 miles. This set the official world record for the highest speed ever recorded by a crewed, powered aircraft, and it remains unbroken to this day.

While pilot, William Knight flew an all-time record speed of Mach 6.7 (4520 miles per hour), the fastest speed flown by a powered and manned piloted aircraft, in 1967, his flight wasn’t the first record setting flight in the X-15. This incredible speed was not even close to the maximum potential of the X-15. A typical commercial passenger jet flies at a speed of about 460 – 575 miles per hour, when cruising at about 36,000 feet, which figures to about 75-85% of the speed of sound. I can’t imagine going any faster than that, much less wrap my head around more than 4520 miles per hour!!

In 1963, pilot Joe Walker flew his X-15 into the history books by flying it to a record altitude of 67 miles and achieving a speed of almost Mach 5 (3794 miles per hour). While there is no sharp physical boundary that marks the end of atmosphere and the beginning of space, it is generally marked at the Karman line, and for purposes of space flight defined as an altitude of 60 miles, although some place the line at 50 miles above Earth’s mean sea level.

The X-15 program continued until 1968, when the rocket planes were retired. On notable pilot was Neil Armstrong, who was also the first man to walk on the Moon, of course. Armstrong made 7 flights in the speedy rocket plane. Also interesting to note is the fact that during the X-15 program, 12 pilots flew a combined 199 flights. Of the 12 pilots, 8

pilots flew a combined 13 flights that exceeded the altitude of 50 miles, thus qualifying these pilots as being astronauts!! Of those 13 flights, two (flown by the same civilian pilot) met the FAI (Féderátion Aéronautique Internationale) definition of 62 miles of outer space. The 5 Air Force pilots qualified for military astronaut wings immediately, while the 3 civilian pilots were eventually awarded NASA astronaut wings in 2005, 35 years after the last X-15 flight.

pilots flew a combined 13 flights that exceeded the altitude of 50 miles, thus qualifying these pilots as being astronauts!! Of those 13 flights, two (flown by the same civilian pilot) met the FAI (Féderátion Aéronautique Internationale) definition of 62 miles of outer space. The 5 Air Force pilots qualified for military astronaut wings immediately, while the 3 civilian pilots were eventually awarded NASA astronaut wings in 2005, 35 years after the last X-15 flight.

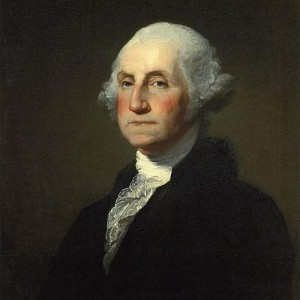

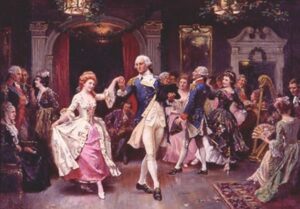

These days, when a president or other elected official is inaugurated, the ceremony is often followed that evening by an inaugural ball. In fact, it is pretty much expected, like the celebration of victory after a long, hard-fought battle. When our first president, George Washington was sworn into office as the first president of the United States, on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City, New York, on April 30, 1789, all tradition concerning elections was brand new. Our country was still trying to figure out what our traditions would be at that point.

These days, when a president or other elected official is inaugurated, the ceremony is often followed that evening by an inaugural ball. In fact, it is pretty much expected, like the celebration of victory after a long, hard-fought battle. When our first president, George Washington was sworn into office as the first president of the United States, on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City, New York, on April 30, 1789, all tradition concerning elections was brand new. Our country was still trying to figure out what our traditions would be at that point.

A week later, on May 3, 1789, George Washington attended a ball in his honor. These days inaugural balls are planned and held with every inauguration. In fact, most presidents attend several balls on inauguration night. Still, in 1789, they were brand new, and it would be another decade before the practice was revived, with the inaugural of James Madison, the fourth president. Dolley, President Madison’s wife, threw a gala for 400 people at Long’s Hotel in Washington. Tickets cost $4.00, which would have amounted to about $100.00 today. That was actually very reasonable, considering that they run about $350.00 today. I suppose that if you were part of high society, you would think nothing of that amount for a ball which would show your support of the new president, as well as, your position in society.

Since Madison’s inaugural ball, the events have become more or less a quadrennial presidential fixture. Today, we think nothing of the event, assuming that it is just part of the grand tradition of our electoral process and seating a new president. Nevertheless, there have been years that the Inaugural Ball has been cancelled. Woodrow Wilson, in 1913, and Warren Harding, in 1921, both passed up balls, citing the need to economize. Franklin Pierce canceled his in 1853 because of the recent death of his son. President Franklin D Roosevelt was another exception, choosing to work through the night rather than attend his first inaugural ball in 1933. He canceled the next three galas because of the Depression and World War II.

At the first ball, Washington danced with many ladies who were considered the cream of New York society. New York was the temporary site of the newly established federal government. Eliza Hamilton, wife of Alexander Hamilton, the treasury secretary, recorded her impressions in her memoirs. She wrote that Washington liked to dance the minuet, a dance she thought was “suited to his dignity and gravity.” In what would seem strange today, Martha Washington apparently did not attend the Inaugural Ball. One month to the day of her husband’s departure for New York, Martha Washington set out on her own triumphant trip to the seat of the new government, thereby becoming our first, First Lady.

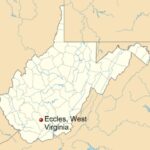

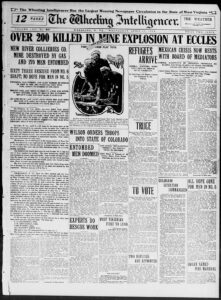

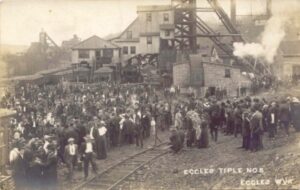

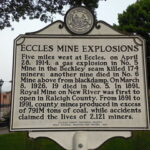

If you lived in Eccles, West Virginia in 1914, you or someone in your family most likely worked at the Eccles Mine Number 5. Eccles was a tiny town in Raleigh County. Mine number 5 was opened in 1905, and by 1914, the mine employed most of the local men and even the teenagers. Life was mundane for the most part. Not much happened in the town, and April 28, 1914 promised to be just another boring day. On that Tuesday morning, dozens of local men and teens left their homes to go to work at the Eccles Mine Number 5, which was one of group of coal mines in West Virginia owned by the New River Colliers Company. Everything was going along fine, when suddenly, at 2:30pm, a sudden explosion rocked the Number 5 mine. In an instant, more than 180 workers who had left home as usual that day, would never go home again.

If you lived in Eccles, West Virginia in 1914, you or someone in your family most likely worked at the Eccles Mine Number 5. Eccles was a tiny town in Raleigh County. Mine number 5 was opened in 1905, and by 1914, the mine employed most of the local men and even the teenagers. Life was mundane for the most part. Not much happened in the town, and April 28, 1914 promised to be just another boring day. On that Tuesday morning, dozens of local men and teens left their homes to go to work at the Eccles Mine Number 5, which was one of group of coal mines in West Virginia owned by the New River Colliers Company. Everything was going along fine, when suddenly, at 2:30pm, a sudden explosion rocked the Number 5 mine. In an instant, more than 180 workers who had left home as usual that day, would never go home again.

The explosion was caused by coal-seam methane. At least 180 men lay dead, at least that was the death roll published as of 2011 by the National Coal Heritage Trail. A monument at the cemetery lists 183 victims, and  the records of the county coroner list 186. When the mine was rocked by a series of violent explosions, parts of the mine collapsed while other parts were heavily damaged, which trapped the miners inside. Of course, the people of Eccles and officials from the mining company rushed to the scene to aid the rescue efforts. Despite their best efforts, it was soon obvious that this would be a recovery effort, and not a rescue. That day, all of the miners in Eccles Mine Number 5 were killed, including five who were under the age of 14 years of age. In addition, nine workers in a nearby mine were killed when deadly gas from Mine Number 5 seeped into their mine. Ironically, one of the men who died in the nearby mine, was an insurance agent from Charleston, West Virginia, who had only gone into the mine to solicit business from the men. He was only there for a few minutes. It was there that the salesman, who had unfortunately chosen that day to visit the mine and sell insurance to its workers, was also killed. The blast and the subsequent damage to the mine, left many of the victim so mangled and torn apart, that most of them could not be positively identified because of their horrific injuries.

the records of the county coroner list 186. When the mine was rocked by a series of violent explosions, parts of the mine collapsed while other parts were heavily damaged, which trapped the miners inside. Of course, the people of Eccles and officials from the mining company rushed to the scene to aid the rescue efforts. Despite their best efforts, it was soon obvious that this would be a recovery effort, and not a rescue. That day, all of the miners in Eccles Mine Number 5 were killed, including five who were under the age of 14 years of age. In addition, nine workers in a nearby mine were killed when deadly gas from Mine Number 5 seeped into their mine. Ironically, one of the men who died in the nearby mine, was an insurance agent from Charleston, West Virginia, who had only gone into the mine to solicit business from the men. He was only there for a few minutes. It was there that the salesman, who had unfortunately chosen that day to visit the mine and sell insurance to its workers, was also killed. The blast and the subsequent damage to the mine, left many of the victim so mangled and torn apart, that most of them could not be positively identified because of their horrific injuries.

In the early 1900s, coal was in great demand. Production in the United States had increased from 50 million tons of coal in 1850 to 250 million tons of coal in 1903. Unfortunately, the increasing demand and the rush to supply, brought with it worsening work conditions. The danger occurred when the men were digging for coal in deep mines, in which chambers of gas lay just underneath. That meant that highly explosive gasses could come into contact with carbide headlamps. The next thing they knew, they had an explosion on their hands. The mine

disaster brought attention to an overall safety problem in the West Virginia mining industry. Sadly…at least in that it didn’t happen sooner, the disaster actually aided the unions’ attempts to improve the workers’ conditions. The labor union helped to ban carbide headlamps in West Virginia. It was suspected that the headlamps were most likely the cause of the Eccles explosion, as well as a second mine explosion 18 years later in Illinois.

disaster brought attention to an overall safety problem in the West Virginia mining industry. Sadly…at least in that it didn’t happen sooner, the disaster actually aided the unions’ attempts to improve the workers’ conditions. The labor union helped to ban carbide headlamps in West Virginia. It was suspected that the headlamps were most likely the cause of the Eccles explosion, as well as a second mine explosion 18 years later in Illinois.

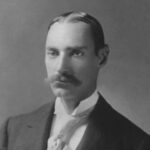

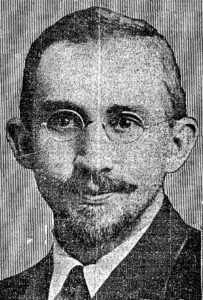

John Jacob Astor IV was born on July 13, 1864 at his parents’ country estate of Ferncliff in Rhinebeck, New York. He was the youngest of five children and only son of William Backhouse Astor Jr, a businessman, collector, and racehorse breeder/owner, and Caroline Webster “Lina” Schermerhorn, a Dutch-American socialite. His four elder sisters were Emily, Helen, Charlotte, and Caroline (“Carrie”). John Astor IV was an American business magnate, real estate developer, investor, writer, lieutenant colonel in the Spanish–American War. He came from a long line of the very prominent Astor family.

John Jacob Astor IV was born on July 13, 1864 at his parents’ country estate of Ferncliff in Rhinebeck, New York. He was the youngest of five children and only son of William Backhouse Astor Jr, a businessman, collector, and racehorse breeder/owner, and Caroline Webster “Lina” Schermerhorn, a Dutch-American socialite. His four elder sisters were Emily, Helen, Charlotte, and Caroline (“Carrie”). John Astor IV was an American business magnate, real estate developer, investor, writer, lieutenant colonel in the Spanish–American War. He came from a long line of the very prominent Astor family.

Astor’s was an accomplished writer, having published “A Journey in Other Worlds” (1894), a science-fiction novel about life in the year 2000 on the planets Saturn and Jupiter. He was also an inventor. He patented several inventions, including a bicycle brake in 1898, a “vibratory disintegrator” used to produce gas from peat moss, and a pneumatic road-improver, and he helped develop a turbine engine. He was a great visionary, and his contributions to the world were amazing.

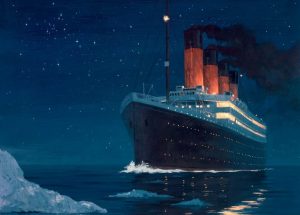

Astor married socialite Ava Lowle Willing on February 17, 1891. The couple had two children, William Vincent Astor (November 15, 1891 – February 3, 1959), businessman and philanthropist, and Ava Alice Muriel Astor (July 7, 1902 – July 19, 1956). The couple divorced in November 1909. Astor IV remarried shortly thereafter, compounding the scandal of his divorce. At the age of 47, Astor married 18-year-old socialite Madeleine Talmage Force, the sister of real estate businesswoman and socialite Katherine Emmons Force. Astor and Force were married in his mother’s ballroom at Beechwood, the family’s Newport, Rhode Island, mansion. There was also much controversy over their 29-year age difference. His son Vincent despised Force, yet he served as best man at his father’s wedding. The couple took an extended honeymoon in Europe and Egypt to wait for the gossip to calm down. Among the few Americans who did not spurn him at this time was Margaret Brown, later fictionalized as The Unsinkable Molly Brown. She accompanied the Astors to Egypt and France. After receiving a call to return to the United States, Brown accompanied the couple back home aboard RMS Titanic.

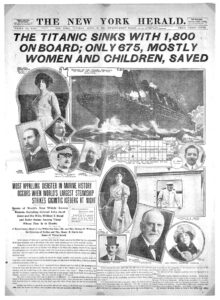

Astor IV died in the sinking of the RMS Titanic during the early hours of April 15, 1912. Astor was the richest passenger aboard the RMS Titanic and was thought to be among the richest people in the world at that time. He was also a true gentleman, who would never have been on a lifeboat without knowing that all the women and children were on lifeboats. Astor IV had a net worth of roughly $87 million when he died, which would be

equivalent to $2.44 billion in 2021. Astor, like his predecessors also made millions in real estate. In 1897, Astor built the Astoria Hotel, “the world’s most luxurious hotel”, in New York City, adjoining the Waldorf Hotel owned by Astor’s cousin and rival, William. Later, the complex became known as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The Waldorf-Astoria was the host location to the United States inquiries into the sinking of the RMS Titanic, on which Astor died.

equivalent to $2.44 billion in 2021. Astor, like his predecessors also made millions in real estate. In 1897, Astor built the Astoria Hotel, “the world’s most luxurious hotel”, in New York City, adjoining the Waldorf Hotel owned by Astor’s cousin and rival, William. Later, the complex became known as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The Waldorf-Astoria was the host location to the United States inquiries into the sinking of the RMS Titanic, on which Astor died.

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

The sinking, brought with it a claim from the Germans that the submarine’s crew had  followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave

followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave  those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

The sinking of RMS Falaba, and Thrasher’s subsequent death, was mentioned again in a memorandum sent by the US government, which was drafted by President Woodrow Wilson himself and addressed to the German government after the German submarine attack on the British passenger ship Lusitania on May 7, 1915, in which 1,201 people were drowned, including 128 Americans. President Wilson’s note was clearly a warning, calling for the US and Germany to come to a full and complete understanding as to the grave situation which had resulted from the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. In response to the warning, Germany abandoned the policy shortly thereafter. However, the policy abandonment was reversed in early 1917, and that was the final straw that put the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917.

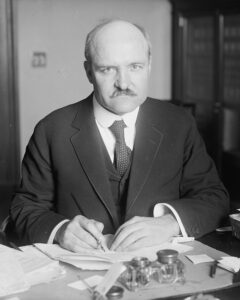

No matter what your opinion is on the use of Daylight Savings Time and Standard Time, the was originally a good reason for it, and that reason still applies today in many ways. The Standard Time Act of 1918, which was also known as the Calder Act (after the senator who sponsored the bill…William M. Calder), was the first United States federal law implementing Standard time and Daylight Saving Time in the United States. Prior to the Calder Act, the railroads had instituted time zones so that the rail schedule could have much needed consistency. Before time zones, no one had any idea when the train was due. It was a big mess. The Time Zone system defined five time zones for the United States and authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to define the limits of each time zone.

No matter what your opinion is on the use of Daylight Savings Time and Standard Time, the was originally a good reason for it, and that reason still applies today in many ways. The Standard Time Act of 1918, which was also known as the Calder Act (after the senator who sponsored the bill…William M. Calder), was the first United States federal law implementing Standard time and Daylight Saving Time in the United States. Prior to the Calder Act, the railroads had instituted time zones so that the rail schedule could have much needed consistency. Before time zones, no one had any idea when the train was due. It was a big mess. The Time Zone system defined five time zones for the United States and authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to define the limits of each time zone.

When the need for Daylight Savings Time came up, the original point of it was to save fuel by setting working hours so they coincided with the hours of natural daylight. While many people may not like that much, I think that a sensible person  can at least see the purpose of it. The act included a section that talked about the repeal of the change in one year, but in the end, it was decided that it was necessary to continue the practice. In fact, they could see no usefulness in repealing it, because the fuel savings had not changed. So, the practice has continued to this day. The Calder Act came about in answer to the European countries, who were already using the practice successfully.

can at least see the purpose of it. The act included a section that talked about the repeal of the change in one year, but in the end, it was decided that it was necessary to continue the practice. In fact, they could see no usefulness in repealing it, because the fuel savings had not changed. So, the practice has continued to this day. The Calder Act came about in answer to the European countries, who were already using the practice successfully.

Those who dislike the practice have been trying to repeal the act for as long as I can remember anyway, and with no success. I suppose that someday, they may succeed, but I’m not sure they will find that life without the time changes will be as amazing as they think. The sun will continue to make its  seasonal adjustments, and without the time changes, we will at some point, find ourselves wishing for another hour of daylight. The first time change to Daylight Saving Time took place on March 19, 1918, and it has been in practice since that time. I, personally, look forward to Daylight Saving Time every year. The longer days and more light make me feel happy, and I find that the few days or a week of adjustment is of little consequence in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, I’m sure I’ll hear lots of differing opinions from my readers. This year, Daylight Saving Time started on March 12, and Standard Time will begin on November 5…just so you know.

seasonal adjustments, and without the time changes, we will at some point, find ourselves wishing for another hour of daylight. The first time change to Daylight Saving Time took place on March 19, 1918, and it has been in practice since that time. I, personally, look forward to Daylight Saving Time every year. The longer days and more light make me feel happy, and I find that the few days or a week of adjustment is of little consequence in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, I’m sure I’ll hear lots of differing opinions from my readers. This year, Daylight Saving Time started on March 12, and Standard Time will begin on November 5…just so you know.

What would make a tiny nation try to invade a nation that is more that 25 times larger, with a population that is at least 8 times larger? It makes no sense, and yet on February 15, 1937, Japan attempted to invade China. Japan, with a total of 60,000 soldiers enter Northern China using planes and tanks. The invasion was something they had studied so they would have a plan before they attempted such an outlandish scheme. The type of conquest they were trying to mimic was that of Kubia Kahn, the Mongol emperor, who in 1271, established the Yuan dynasty and formally claimed orthodox succession from prior Chinese dynasties. The Yuan dynasty came to rule over most of present-day China, Mongolia, Korea, southern Siberia, and other adjacent areas. Kahn also amassed influence in the Middle East and Europe as khagan. By 1279, the Yuan conquest of the Song dynasty was completed, and Kahn became the first non-Han emperor to rule all of China proper.

What would make a tiny nation try to invade a nation that is more that 25 times larger, with a population that is at least 8 times larger? It makes no sense, and yet on February 15, 1937, Japan attempted to invade China. Japan, with a total of 60,000 soldiers enter Northern China using planes and tanks. The invasion was something they had studied so they would have a plan before they attempted such an outlandish scheme. The type of conquest they were trying to mimic was that of Kubia Kahn, the Mongol emperor, who in 1271, established the Yuan dynasty and formally claimed orthodox succession from prior Chinese dynasties. The Yuan dynasty came to rule over most of present-day China, Mongolia, Korea, southern Siberia, and other adjacent areas. Kahn also amassed influence in the Middle East and Europe as khagan. By 1279, the Yuan conquest of the Song dynasty was completed, and Kahn became the first non-Han emperor to rule all of China proper.

So, with dreams of power and world domination, among other things, including a need for the resources Japan lacked and China had, the Japanese army under Emperor Hirohito made the decision to attack the much larger  and more populated China. They threatened to bottle up 400,000 Chinese people on China’s central front. The attack area was approximately 20 miles, from the Yellow River to the Henan Capital provincial (Kaifeng). The Japanese Army displayed far superior air power and many more combat troops during the Japanese onslaught. In fact, their might could easily be called terrifying. China was helpless at stopping the Japanese forces from occupying Shanghai, and they were barely able prevent the invasion of Japan on the capital. The Chinese desperately tried to fight back with small caliber weapons against the heavy artillery fire power, air and naval might, and armored defenses of Japan. While they were severely outgunned, the bravery, stubbornness and determination of the Chinese made it possible for the country to withstand three months of defending Shanghai. Nevertheless, in the end, Shanghai fell, and Japan gained control over the city. The best of China’s troops were defeated. Still, the Japanese were surprised at the length of time that the Chinese troops were able to make a stand for their capital city. Because of their military superiority, the Japanese fully expected a short battle and a swift victory. They were not prepared for the one variable…the determination of the Chinese

and more populated China. They threatened to bottle up 400,000 Chinese people on China’s central front. The attack area was approximately 20 miles, from the Yellow River to the Henan Capital provincial (Kaifeng). The Japanese Army displayed far superior air power and many more combat troops during the Japanese onslaught. In fact, their might could easily be called terrifying. China was helpless at stopping the Japanese forces from occupying Shanghai, and they were barely able prevent the invasion of Japan on the capital. The Chinese desperately tried to fight back with small caliber weapons against the heavy artillery fire power, air and naval might, and armored defenses of Japan. While they were severely outgunned, the bravery, stubbornness and determination of the Chinese made it possible for the country to withstand three months of defending Shanghai. Nevertheless, in the end, Shanghai fell, and Japan gained control over the city. The best of China’s troops were defeated. Still, the Japanese were surprised at the length of time that the Chinese troops were able to make a stand for their capital city. Because of their military superiority, the Japanese fully expected a short battle and a swift victory. They were not prepared for the one variable…the determination of the Chinese  people. Morale plummeted over the heavy losses incurred, but not for long.

people. Morale plummeted over the heavy losses incurred, but not for long.

I sometimes wonder if these heads of governments really think that they can somehow control the world, or even, if they really think they can control the country they have invaded. The main reasons that nations and borders change as often as they do, is that people will only live under oppression for so long. Then, they will fight back. As to the heads of nations and ruling the world. While they might be the “head” of their nation, in a situation of world domination, I seriously doubt if any of these national leaders would be the one in control.

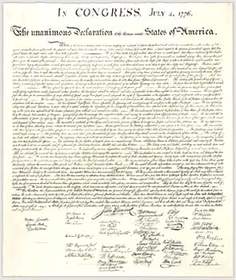

When a country is fighting for recognition, one of the most important events is when other countries recognize your country as being an independent nation. It’s rather hard to conduct business with other nations, if you are viewed as a rouge or non-existent nation. That was the position the United States found themselves in right after the Declaration of Independence was adopted. Just because a country adopts its declaration of independence, doesn’t mean that it’s a done deal. That document can and has been the cause of major wars. The United States was no exception on the war end of that either. They fought long and hard to win that declared independence from Great Britain.

When a country is fighting for recognition, one of the most important events is when other countries recognize your country as being an independent nation. It’s rather hard to conduct business with other nations, if you are viewed as a rouge or non-existent nation. That was the position the United States found themselves in right after the Declaration of Independence was adopted. Just because a country adopts its declaration of independence, doesn’t mean that it’s a done deal. That document can and has been the cause of major wars. The United States was no exception on the war end of that either. They fought long and hard to win that declared independence from Great Britain.

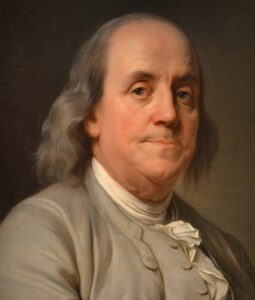

Finally, the coveted recognition came when on December 17, 1777, the French foreign minister, Charles Gravier, count of Vergennes, officially acknowledged the United States as an independent nation. It came after news of the Continental Army’s overwhelming victory against the British General John Burgoyne at Saratoga. The victory gave Benjamin Franklin new leverage in his efforts to rally French support for the American rebels. Although the victory occurred in October, news did not reach France until December 4th. Remember that this mail system was worse than “snail mail” ever was. Messages had to be sent by ship across the ocean.

Benjamin Franklin had quickly mustered French support upon his arrival in December 1776. France’s humiliating loss of North America to the British in the Seven Years’ War made the French eager to see an American victory. Still, the French king worried about the consequences of backing “the rebels” openly. You can’t really blame him because an act like that could bring war to his own country. Still, he did back them in every other way. In May 1776, Louis XVI sent unofficial aid to the Continental forces and the playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais helped Franklin organize private assistance for the American cause.

Benjamin Franklin, who often wore a fur cap, captured the imagination of Parisians as an American man of nature and his well-known social charms stirred French passions for all things American. His personality made him the toast of Parisian society. He was very knowledgeable, and he had a way of enchanting groups of people

with his wide-ranging knowledge, social graces, and witty conversation. Nevertheless, he was not allowed to appear at court, so any legal assistance he might have offered in the defense of the United States, was never heard.

with his wide-ranging knowledge, social graces, and witty conversation. Nevertheless, he was not allowed to appear at court, so any legal assistance he might have offered in the defense of the United States, was never heard.

Finally, with the impressive and long-awaited rebel victory at Saratoga, Louis XVI was convinced that the American rebels had some hope of defeating the British empire. His enthusiasm for the victory paired with French Foreign Minister Gravier’s concern that the loss of Philadelphia to the British would lead Congress to surrender, gave Franklin two influential allies with two powerful, albeit opposing reasons for officially backing the American cause, and so it was that a formal treaty of alliance with the United States followed on February 6, 1778.

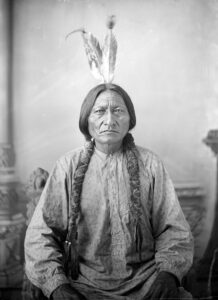

Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. The Hunkpapa Lakota is a branch of the Sioux tribe. Sitting Bull was a rather charismatic person, and people were willing to follow him because of it. He was a rather mysterious historical figure. He was not impulsive, nor was he calm. Sitting Bull had a strange personality. He was most serious when he seemed to be joking. He also possessed the power of sarcasm, and he used it to his advantage. These things are likely what made him a good leader for his people.

Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. The Hunkpapa Lakota is a branch of the Sioux tribe. Sitting Bull was a rather charismatic person, and people were willing to follow him because of it. He was a rather mysterious historical figure. He was not impulsive, nor was he calm. Sitting Bull had a strange personality. He was most serious when he seemed to be joking. He also possessed the power of sarcasm, and he used it to his advantage. These things are likely what made him a good leader for his people.

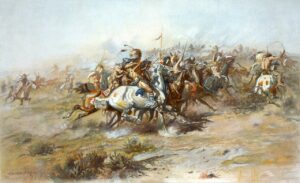

Sitting Bull was a man given to having visions, and before the Battle of the Little Bighorn, he had a vision in which he saw many soldiers, “as thick as grasshoppers,” falling upside down into the Lakota camp. The Hunkpapa Lakota people took the vision as a sign of a major victory in which many soldiers would be killed…and maybe it was. Just three weeks later, on June 25, 1876, the confederated Lakota tribes, along with the Northern Cheyenne tribe, defeated the 7th Cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, decimating Custer’s battalion. The battle and it’s timing seemed to bear out Sitting Bull’s prophetic vision. Again, Sitting Bull’s leadership inspired his people to  a major victory.

a major victory.

Of course, the United States government immediately sent thousands more soldiers to the area, in response to the battle. Any Indians who were in small groups or alone were a target, as were villages of peaceful Indians. Many were forced to surrender over the next year, but Sitting Bull refused to. In May 1877, he led his band north to Wood Mountain, North-West Territories, which is now Saskatchewan. Canada. Sitting Bull stayed in that area until 1881, at which time he and most of his band returned to US territory and surrendered to US forces.

Sitting Bull’s charismatic personality helped him out again when he went to work as a performer with Buffalo  Bill’s Wild West show for a while, before returning to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota. That became one of the biggest mistakes Sitting Bull would ever make. Due to fears that he would use his influence to support the Ghost Dance movement, Indian Service agent James McLaughlin at Fort Yates ordered his arrest on December 15, 1890. Sitting Bull’s followers refused to go quietly, and in the struggle with police, Sitting Bull was shot in the side and head by Standing Rock policemen Lieutenant Bull Head and Red Tomahawk. His body was taken to nearby Fort Yates for burial. In 1953, his Lakota family exhumed what were believed to be his remains, reburying them near Mobridge, South Dakota, near his birthplace.

Bill’s Wild West show for a while, before returning to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota. That became one of the biggest mistakes Sitting Bull would ever make. Due to fears that he would use his influence to support the Ghost Dance movement, Indian Service agent James McLaughlin at Fort Yates ordered his arrest on December 15, 1890. Sitting Bull’s followers refused to go quietly, and in the struggle with police, Sitting Bull was shot in the side and head by Standing Rock policemen Lieutenant Bull Head and Red Tomahawk. His body was taken to nearby Fort Yates for burial. In 1953, his Lakota family exhumed what were believed to be his remains, reburying them near Mobridge, South Dakota, near his birthplace.