United States

We all know that war is a nasty, messy, vicious event. Nevertheless, sometimes war is necessary. Unfortunately, in our world, evil exists, and sometimes the evil is in the form of a dictator, a nation, or a religious group. Wars might be fought differently, but the end result is the same…death and destruction. Still, most wars have an ending point. One side surrenders, and admits defeat. That might seem like the end of the story, but it isn’t. All too often the process of cleaning up the mess after the war, takes far longer than the war itself. In fact, sometimes the cleanup never really happens at all. Such was the case with landmines in Angola. These mines are a legacy of over four decades of fighting during a 14 year war of independence against its former colonial ruler of Portugal and another 30 years of civil war. Like people who put signs up to advertise a garage sale, sometimes they don’t remember where all the landmines were, or maybe they did, and simply didn’t care. Either way, the landmines were killing and maiming people…innocent people. That was the mission my 16th cousin once removed, Princess Diana took upon herself. She wanted an international ban on landmines. Her comments, which were made during a January 15, 1997 visit to Angola to see for herself some of the victims of landmines, were seen as out of step with government policy by the Junior Defense Minister, Earl Howe, who described the princess as a “loose cannon”, ill-informed on the issue of anti-personnel landmines. Nevertheless, Diana was right about the weapons of war that were left behind. The task of cleaning up the mess may have been a daunting one, but the result of leaving them behind was gruesome.

We all know that war is a nasty, messy, vicious event. Nevertheless, sometimes war is necessary. Unfortunately, in our world, evil exists, and sometimes the evil is in the form of a dictator, a nation, or a religious group. Wars might be fought differently, but the end result is the same…death and destruction. Still, most wars have an ending point. One side surrenders, and admits defeat. That might seem like the end of the story, but it isn’t. All too often the process of cleaning up the mess after the war, takes far longer than the war itself. In fact, sometimes the cleanup never really happens at all. Such was the case with landmines in Angola. These mines are a legacy of over four decades of fighting during a 14 year war of independence against its former colonial ruler of Portugal and another 30 years of civil war. Like people who put signs up to advertise a garage sale, sometimes they don’t remember where all the landmines were, or maybe they did, and simply didn’t care. Either way, the landmines were killing and maiming people…innocent people. That was the mission my 16th cousin once removed, Princess Diana took upon herself. She wanted an international ban on landmines. Her comments, which were made during a January 15, 1997 visit to Angola to see for herself some of the victims of landmines, were seen as out of step with government policy by the Junior Defense Minister, Earl Howe, who described the princess as a “loose cannon”, ill-informed on the issue of anti-personnel landmines. Nevertheless, Diana was right about the weapons of war that were left behind. The task of cleaning up the mess may have been a daunting one, but the result of leaving them behind was gruesome.

Of course, these weren’t the only messes that needed to be cleaned up after a war. There were buildings to be rebuilt, the dead to bury, the economy to build up, and the government often had to be restructured. The country might have been the enemy, but if things weren’t handled right after the surrender, the same evil people might move right back into power. Of course, cleaning up the mess…often known as policing the nation that has now surrendered, is no easy task either. Most people don’t want the winning army there. Their country is nothing like it used to be. Some believe that is a good thing, but it was still their home, and now everything feels…wrong. Their homes are destroyed, food is can be scarce…water too. Everything they have known for their whole life is gone. No wonder they don’t want the army there…or maybe they secretly do, because their home has become just a very scary place. I suppose that is why a part of the surrender agreements include restoration of the country, and the new government and police.

One more part of cleaning up the mess is the task of trying the perpetrators for their war crimes. That was the main reason that Hitler took his own life. He knew that he would be tried and convicted of the crimes he had committed, and he couldn’t face what would follow. He would have been left to the mercy of his countrymen,

and he would have ended up being hung, like Saddam Hussein was for his war crimes. A dictator can’t brutally kill the people who he is in power over and not be hated…truly hated, no matter what the people act like when they are forced to act loyal. The trials for war crimes in many ways seems to the world, as if one nation is trying to be the world police. The United States has been accused of this before, but the reality remains, that someone has to try these evil criminals, and someone has to clean up the mess. In the absence of another nation to step up, the job usually falls to the United States.

and he would have ended up being hung, like Saddam Hussein was for his war crimes. A dictator can’t brutally kill the people who he is in power over and not be hated…truly hated, no matter what the people act like when they are forced to act loyal. The trials for war crimes in many ways seems to the world, as if one nation is trying to be the world police. The United States has been accused of this before, but the reality remains, that someone has to try these evil criminals, and someone has to clean up the mess. In the absence of another nation to step up, the job usually falls to the United States.

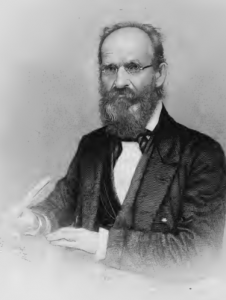

Platt Rogers Spencer, who is my 3rd cousin 5 times removed, was a social activist. In other words, he saw something that was socially or morally wrong, such as slavery, and he actively fought against it. These days that would mean protesting, lobbying, and blogging against it. Social activism has it’s place, but should be done in the proper way. Platt Spencer was a zealous promoter of the antislavery movement…an honorable cause. He was a prominent advocate of the abstinence movements. He was instrumental in founding business colleges in the United States, and was in organizing several business colleges in the United States, and he was an instructor in business colleges throughout the country.

Platt Rogers Spencer, who is my 3rd cousin 5 times removed, was a social activist. In other words, he saw something that was socially or morally wrong, such as slavery, and he actively fought against it. These days that would mean protesting, lobbying, and blogging against it. Social activism has it’s place, but should be done in the proper way. Platt Spencer was a zealous promoter of the antislavery movement…an honorable cause. He was a prominent advocate of the abstinence movements. He was instrumental in founding business colleges in the United States, and was in organizing several business colleges in the United States, and he was an instructor in business colleges throughout the country.

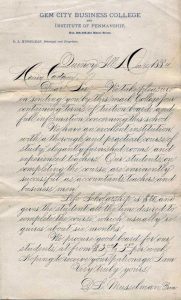

In 1815, Spencer taught his first writing class, and in New York, where he founded the Spencer Seminary in Jericho, housed in a log cabin. From 1816 to 1821, he was a clerk and a book keeper and, from 1821 to 1824, he studied in law, Latin, English literature and penmanship. He also taught in a common school and wrote up merchants’ books.  In 1824, he contemplated entering college with a view to preparing for the ministry, but, due to his alcoholism, which was aggravated by the prevalent drinking customs of the time, he did not. He struggled with alcoholism for a number of years. He then taught in Ohio, where in 1832, he was able to withdraw from alcohol completely, becoming a total abstainer. He advocated abstaining from alcohol for the remainder of his life. Soon after his recovery from alcoholism, he was elected to public office, as county treasurer of Ashtabula County, Ohio for twelve years. He also was a founding member of the Ashtabula County Historical Society established in 1838 and he was instrumental in collecting the early history of Ashtabula County, Ohio.

In 1824, he contemplated entering college with a view to preparing for the ministry, but, due to his alcoholism, which was aggravated by the prevalent drinking customs of the time, he did not. He struggled with alcoholism for a number of years. He then taught in Ohio, where in 1832, he was able to withdraw from alcohol completely, becoming a total abstainer. He advocated abstaining from alcohol for the remainder of his life. Soon after his recovery from alcoholism, he was elected to public office, as county treasurer of Ashtabula County, Ohio for twelve years. He also was a founding member of the Ashtabula County Historical Society established in 1838 and he was instrumental in collecting the early history of Ashtabula County, Ohio.

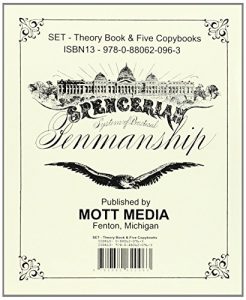

In 1840, Platt developed a beautiful and unique style of writing and named it after himself, calling it Spencerian Script. The penmanship style quickly became the standard in the United States from 1850 to 1925. It was considered the American de facto standard writing style for business correspondence prior to the widespread adoption of the typewriter. Platt used various existing styles as the inspiration for his unique oval-based style. His style could be written quickly and legibly and yet it still looked elegant, which made it perfect for business  correspondence, as well as personal letters. Immediately following his development of the Spencerian Script style, Platt began teaching it in the schools he established for the purpose of teaching his penmanship style. As soon as his students began to graduate, they started replicas of the Spencerian Script abroad, and then in 1850 it reached the common schools. Unfortunately, Platt Spencer never got to see the full success of his unique penmanship, because he died on May 16, 1864. Nevertheless, his sons made it their mission to bring their late father’s dream to fruition. They accomplished that feat by distributing Spencer’s previously unpublished book, Spencerian Key to Practical Penmanship, in 1866. Spencerian Script was gradually replaced in primary schools with the simpler Palmer Method developed by Austin Norman Palmer…which is sadly very plain by comparison. The Coca-Cola Company famously used Spencerian Script in its now famous logo, and continues to do so to this day.

correspondence, as well as personal letters. Immediately following his development of the Spencerian Script style, Platt began teaching it in the schools he established for the purpose of teaching his penmanship style. As soon as his students began to graduate, they started replicas of the Spencerian Script abroad, and then in 1850 it reached the common schools. Unfortunately, Platt Spencer never got to see the full success of his unique penmanship, because he died on May 16, 1864. Nevertheless, his sons made it their mission to bring their late father’s dream to fruition. They accomplished that feat by distributing Spencer’s previously unpublished book, Spencerian Key to Practical Penmanship, in 1866. Spencerian Script was gradually replaced in primary schools with the simpler Palmer Method developed by Austin Norman Palmer…which is sadly very plain by comparison. The Coca-Cola Company famously used Spencerian Script in its now famous logo, and continues to do so to this day.

For many years the United States and Russia, at one time the Soviet Union, have had an unusual relationship. Depending on what Russia is trying to do, they might be our enemy, or they might be our ally. I understand that different nations have different goals, different values, and different motives, but it still seems odd to me that in one war, we could be allies and in another war, we become enemies. It could seem a little bit like two childhood friends, who are best friends one minute and worst enemies the next minute. The only exception would have to be the fact that trust doesn’t really fit in with the rest of the characteristics of the relationship between the United States and Russia. I suppose that becoming allies then, becomes a matter of finding an enemy who is doing things you can’t accept, and another enemy who agrees with you on your dislike of the actions of the first enemy…if that makes sense. I think that my prior statement makes as much sense as the United States being an ally of Russia, but that is what they have been…sometimes. I think the most difficult part of that kind of relationship would have to be the point when the relationship turns from ally to enemy again, because it really is inevitable.

For many years the United States and Russia, at one time the Soviet Union, have had an unusual relationship. Depending on what Russia is trying to do, they might be our enemy, or they might be our ally. I understand that different nations have different goals, different values, and different motives, but it still seems odd to me that in one war, we could be allies and in another war, we become enemies. It could seem a little bit like two childhood friends, who are best friends one minute and worst enemies the next minute. The only exception would have to be the fact that trust doesn’t really fit in with the rest of the characteristics of the relationship between the United States and Russia. I suppose that becoming allies then, becomes a matter of finding an enemy who is doing things you can’t accept, and another enemy who agrees with you on your dislike of the actions of the first enemy…if that makes sense. I think that my prior statement makes as much sense as the United States being an ally of Russia, but that is what they have been…sometimes. I think the most difficult part of that kind of relationship would have to be the point when the relationship turns from ally to enemy again, because it really is inevitable.

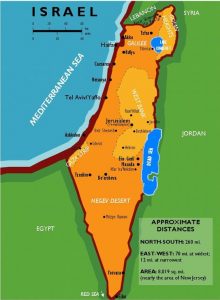

It is historical fact, that over the years the Untied States and Russia have found themselves on opposite sides of a war…even threatening to blow each other up with a nuclear bomb, but so far, both have also hesitated to take things to that level, because the start of that kind of war would likely bring inhalation, since each country has the ability to know that such an attack has started. It’s a good thing that technology has given us that ability, because if we had the nuclear bombs we now have and no way the know that an attack had commenced, one nation could easily wipe out another. Russia has often tested the United States when they have moved to attack weaker nations for the things they wanted, such as oil, food, and power. Their actions left the United States with no other options but to fight against the nation that was sometimes an ally. It has happened in the past, and it will happen again in the future, because Russia remains an enemy of Israel, and that at the very least, is a situation in which the United States would want to act. Israel has always been our ally…not a sometimes ally, and if we are able, we would protect them. At least I pray that we would.

The biggest factor to affect the relationships between countries is their leaders. Most of the history of the United States has found our leaders acknowledging and even embracing our longtime, and very important friendship with Israel. Nevertheless, some leaders, like our current president, have made it clear that Israel is in a precarious position in the world. I am thankful that our president elect has told us that he will be a friend to Israel and other nations that have been oppressed by power nations in the past. It remains to be seen, exactly where Russia will be in this scenario. It is my hope that they will be an ally, but I know that they are still an enemy of our friends, and that can only make us sometimes allies.

The biggest factor to affect the relationships between countries is their leaders. Most of the history of the United States has found our leaders acknowledging and even embracing our longtime, and very important friendship with Israel. Nevertheless, some leaders, like our current president, have made it clear that Israel is in a precarious position in the world. I am thankful that our president elect has told us that he will be a friend to Israel and other nations that have been oppressed by power nations in the past. It remains to be seen, exactly where Russia will be in this scenario. It is my hope that they will be an ally, but I know that they are still an enemy of our friends, and that can only make us sometimes allies.

It’s amazing to me that one act of hate can bring so many people to war, but that was what happened with World War I. On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo, Bosnia. The assassin, Gavrilo Princip was an ethnic Serb and Yugoslav nationalist from the group Young Bosnia, which was supported by the Black Hand, a nationalist organization in Serbia. The outraged Austrian people and its government threatened mobilization of troops to seek vengeance for their beloved leader and his family.

It’s amazing to me that one act of hate can bring so many people to war, but that was what happened with World War I. On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo, Bosnia. The assassin, Gavrilo Princip was an ethnic Serb and Yugoslav nationalist from the group Young Bosnia, which was supported by the Black Hand, a nationalist organization in Serbia. The outraged Austrian people and its government threatened mobilization of troops to seek vengeance for their beloved leader and his family.

The crisis escalated as the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia came to involve Russia, Germany, France, and ultimately Belgium and Great Britain. By mid-August of 1914, the crisis had become a full blown war, with Germany, Austria Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, known as the Central Powers, against Great Britain, France, Russia, Italy and Japan, the Allied Powers. The United States would also enter the war as a part of the Allied Powers in 1917. Other factors came into play during the diplomatic crisis that preceded the war, such as misperceptions of intent in that Germany believed that Britain would remain neutral, the belief that war was inevitable, and the speed of the crisis, which was exacerbated by delays and misunderstandings in diplomatic communications. The four years of the Great War…as it was dubbed…saw unprecedented levels of carnage and destruction, thanks to grueling trench warfare and the introduction of modern weaponry such as machine guns, tanks and chemical weapons. By the time World War I ended in the defeat of the Central Powers in November 1918, more than 9 million soldiers had been killed and 21 million more wounded.

Evil exists in this world, and it gets worse every day, and assassinations are not new. Chanakya, 350–283 BC, an Indian teacher, philosopher and royal advisor, wrote about assassinations in detail in his political treatise Arthashastra. Later, his student Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya Empire of India, made use of assassinations against some of his enemies, including two of Alexander’s generals Nicanor and Philip. I suppose it should not be a surprise, yet every assassination brings with it shock, fear, and rage.

Countless wars have been fought over one nation’s ruler being killed by someone from another nation. War will be a part of our world until the end of time, but that in no way lessens the worry, fear, and sadness that war always brings. Still, like the Allies of World War I, we cannot let one group or nation hold power over another group or nation…which also explains the need to destroy ISIS.

Countless wars have been fought over one nation’s ruler being killed by someone from another nation. War will be a part of our world until the end of time, but that in no way lessens the worry, fear, and sadness that war always brings. Still, like the Allies of World War I, we cannot let one group or nation hold power over another group or nation…which also explains the need to destroy ISIS.

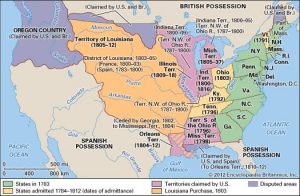

From the time the United States first declared their independence, there was a dispute over the border between the United States and its northern neighbor, Canada. In 1818, the situation finally got to a point whereby a final decision had to be made. It was determined that a convention needed to be held to handle the dispute. The convention, known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, was to discuss fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The Treaty of 1818 was signed during the presidency of James Monroe, and it resolved the boundary between the United States and Canada, then owned by the United Kingdom, once and for all. The treaty allowed for joint occupation and settlement of the Oregon Country, known to the British and in Canadian history as the Columbia District of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and also took in New Caledonia, near Australia.

From the time the United States first declared their independence, there was a dispute over the border between the United States and its northern neighbor, Canada. In 1818, the situation finally got to a point whereby a final decision had to be made. It was determined that a convention needed to be held to handle the dispute. The convention, known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, was to discuss fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The Treaty of 1818 was signed during the presidency of James Monroe, and it resolved the boundary between the United States and Canada, then owned by the United Kingdom, once and for all. The treaty allowed for joint occupation and settlement of the Oregon Country, known to the British and in Canadian history as the Columbia District of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and also took in New Caledonia, near Australia.

It was ultimately decided that the boundary line should be a straight one, because it would be easier to survey. The prior boundaries were based on watersheds, and were difficult to survey. The treaty marked both the United Kingdom’s last permanent major loss of territory in what is now the Continental United States and the United States’ only permanent significant cession of North American territory to a foreign power. Britain ceded all of Rupert’s Land south of the 49th parallel and west to the Rocky Mountains, including all of the Red River Colony south of that latitude, while the United States ceded the northernmost tip of the territory of Louisiana above the 49th parallel.

Of course, the prior border from the Great Lakes to the east coast, was already established, so it isn’t straight, but the northwestern border is a straight line. I always thought that was odd, and didn’t know why it was that way. I don’t know if I was not paying attention in history class, which was not my favorite subject in my youth, although I don’t really know why it wasn’t, because now I find it quite fascinating. It’s interesting to find out that the northern border was simply a matter of convenience, and a bit of the barter system, if you will. In order to solve the border war, of sorts, Canada (United Kingdom) gave a little, and the United States gave a little. The end result was a clear cut border, and really, peaceful neighbors. I think the was a good way to settle things.

Of course, the prior border from the Great Lakes to the east coast, was already established, so it isn’t straight, but the northwestern border is a straight line. I always thought that was odd, and didn’t know why it was that way. I don’t know if I was not paying attention in history class, which was not my favorite subject in my youth, although I don’t really know why it wasn’t, because now I find it quite fascinating. It’s interesting to find out that the northern border was simply a matter of convenience, and a bit of the barter system, if you will. In order to solve the border war, of sorts, Canada (United Kingdom) gave a little, and the United States gave a little. The end result was a clear cut border, and really, peaceful neighbors. I think the was a good way to settle things.

The United States and Russia have long been frenemies, truth be told, but in October of 1962, no one would have called them that. The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the two super powers to the brink of a nuclear conflict. As we all know, that would have been devastating for the inhabitants of the earth, and in the end, both countries agreed that we could not let things escalate to that level again. In June of 1963, American and Russian representatives agreed to establish a “hot line” between Moscow and Washington DC. The idea was to speed communication between the two governments to prevent an accidental war.

The United States and Russia have long been frenemies, truth be told, but in October of 1962, no one would have called them that. The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the two super powers to the brink of a nuclear conflict. As we all know, that would have been devastating for the inhabitants of the earth, and in the end, both countries agreed that we could not let things escalate to that level again. In June of 1963, American and Russian representatives agreed to establish a “hot line” between Moscow and Washington DC. The idea was to speed communication between the two governments to prevent an accidental war.

By August of 1963, the system was ready to be tested. American teletype machines were installed in the Kremlin and at the Pentagon. Many people have thought that the machine at the Pentagon was actually in the White House, but that is incorrect. The two nations exchanged  encoding devises so that they could decipher the messages. This would allow the two nations to message each other in a matter of minutes. That would be somewhat slow in today’s high tech world of cell phones and texting, but in those days, it was state of the art. Once received, the message would have to be deciphered, which did slow things down a bit, but again, at that time, it was state of the art. The two teletype machines were connected by a 10,000 mile long cable with “scramblers” along the way to ensure that the messages could not be intercepted by unauthorized personnel.

encoding devises so that they could decipher the messages. This would allow the two nations to message each other in a matter of minutes. That would be somewhat slow in today’s high tech world of cell phones and texting, but in those days, it was state of the art. Once received, the message would have to be deciphered, which did slow things down a bit, but again, at that time, it was state of the art. The two teletype machines were connected by a 10,000 mile long cable with “scramblers” along the way to ensure that the messages could not be intercepted by unauthorized personnel.

On August 30, the United States sent its first message to the Soviet Union over the hot line: “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog’s back 1234567890.” The message was chosen because it used every letter and number key on the teletype machine in order to see that each was in working order. Moscow returned a message in Russian indicating that every key had worked properly. In the end, the hot line was never needed  to prevent war, but instead has become a novelty item, used as a prop in movies about nuclear disaster. Fail Safe and Dr Strangelove were two movies that utilized the machines. The reality was that the two superpowers had come so close to mutual destruction back in 1962, that neither had much stomach for the proposed threat. They understood that communication was key in stopping a nuclear war. Of course, that has not stopped other nations from threatening to use nuclear weapons against other nations of the world. The Cold War ended a long time ago, but the “hot line” is still in operation between the two superpowers, and has since been supplemented by a direct secure telephone connection in 1999.

to prevent war, but instead has become a novelty item, used as a prop in movies about nuclear disaster. Fail Safe and Dr Strangelove were two movies that utilized the machines. The reality was that the two superpowers had come so close to mutual destruction back in 1962, that neither had much stomach for the proposed threat. They understood that communication was key in stopping a nuclear war. Of course, that has not stopped other nations from threatening to use nuclear weapons against other nations of the world. The Cold War ended a long time ago, but the “hot line” is still in operation between the two superpowers, and has since been supplemented by a direct secure telephone connection in 1999.

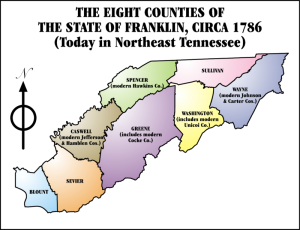

Have you heard of the nation of Frankland…or maybe the nation of Franklin? I hadn’t either, but it was a real place. Early in the history of the United States, its people operated on somewhat limited trust of the government…probably due to the treatment they received in England. In April of 1784, the state of North Carolina ceded its western land claims between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi River to the United States Congress. The settlers who lived in that area, known as the Cumberland River Valley, had already formed their own government from 1772 to 1777, and their distrust of Congress led the to worry that the area might be sold to Spain or France to pay off war debts owed them by the government. Due to their concerns, North Carolina retracted its cession and started to organize an administration for the territory.

Have you heard of the nation of Frankland…or maybe the nation of Franklin? I hadn’t either, but it was a real place. Early in the history of the United States, its people operated on somewhat limited trust of the government…probably due to the treatment they received in England. In April of 1784, the state of North Carolina ceded its western land claims between the Allegheny Mountains and the Mississippi River to the United States Congress. The settlers who lived in that area, known as the Cumberland River Valley, had already formed their own government from 1772 to 1777, and their distrust of Congress led the to worry that the area might be sold to Spain or France to pay off war debts owed them by the government. Due to their concerns, North Carolina retracted its cession and started to organize an administration for the territory.

At the same time, representatives from Washington, Sullivan, Spencer (modern-day Hawkins) and Greene  counties declared their independence from North Carolina. Then, in May, they petitioned the United States Congress for statehood as Frankland. The simple majority favored the petition, but Congress could not get the two thirds majority to pass it…not even when the people decided to change the name to Franklin, in the hope of winning favor with Benjamin Franklin and some of the others.

counties declared their independence from North Carolina. Then, in May, they petitioned the United States Congress for statehood as Frankland. The simple majority favored the petition, but Congress could not get the two thirds majority to pass it…not even when the people decided to change the name to Franklin, in the hope of winning favor with Benjamin Franklin and some of the others.

When the petition failed to pass, the people in the area grew angry, and decided to defy Congress. On this day, August 23, 1784, they ceded from the union and functioned as the Free Republic of Franklin (Frankland) for four years. During that time, they had their own constitution, Indian treaties and legislated system of barter in lieu of currency. Two years into the Free Republic of Franklin’s history, North Carolina set up their own parallel government in the area. The economy was weak, and never really gained ground, so the governor, John Sevier approached the Spanish for aid. That move brought a feeling of terror in the government of North Carolina, and they arrested Sevier. The situation worsened when the Cherokee, Chickamauga and Chickasaw began to attack settlements within Franklin’s borders in 1788. Franklin quickly rejoined North Carolina to gain its militia’s protection from attack.

It was a short life for the little nation of Franklin, and eventually they wouldn’t even belong to North Carolina, but rather became a part of the state of Tennessee. It just goes to show that the growing pains of a nation can  take on many forms to reach their destiny as a whole nation. Some changes are good ones, and continue on into the future, and others are not so good, and are sometimes absorbed into the fabric of history and time, and end up looking nothing like the change they started out to be.

take on many forms to reach their destiny as a whole nation. Some changes are good ones, and continue on into the future, and others are not so good, and are sometimes absorbed into the fabric of history and time, and end up looking nothing like the change they started out to be.

Before Bob and I were even married, I knew that he was related to one of our presidents…namely James Knox Polk. Since then, I have found that we are actually related to several presidents, but James K Polk remains the one with whom the link seems the most obvious. Still, while I knew of the relationship, there were things about him that I didn’t know. One of the most notable being his connection to the Smithsonian Institution. In 1829, one James Smithson died in Italy, and while most people would not think that would have impacted the United States of America, it actually did. So, who was Smithson anyway. Smithson had been a fellow of the venerable Royal Society of London from the age of 22, publishing numerous scientific papers on mineral composition, geology, and chemistry. In 1802, he overturned popular scientific opinion by proving that zinc carbonates were true carbonate minerals, and one type of zinc carbonate was later named Smithsonite in his honor.

Before Bob and I were even married, I knew that he was related to one of our presidents…namely James Knox Polk. Since then, I have found that we are actually related to several presidents, but James K Polk remains the one with whom the link seems the most obvious. Still, while I knew of the relationship, there were things about him that I didn’t know. One of the most notable being his connection to the Smithsonian Institution. In 1829, one James Smithson died in Italy, and while most people would not think that would have impacted the United States of America, it actually did. So, who was Smithson anyway. Smithson had been a fellow of the venerable Royal Society of London from the age of 22, publishing numerous scientific papers on mineral composition, geology, and chemistry. In 1802, he overturned popular scientific opinion by proving that zinc carbonates were true carbonate minerals, and one type of zinc carbonate was later named Smithsonite in his honor.

James Smithson’s will had one odd footnote to it, that in the end, would change everything. Smithson didn’t have much family, in fact, he had just one nephew at the time of his passing. His entire estate was willed to that nephew, with one condition attached to it. If his nephew should die without children, the entire estate was to go to “the United States of America, to found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” Smithson’s curious bequest to a country that he had never visited garnered significant attention on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. James Smithson was a scientist, who wasn’t well known, but he apparently had a dream for the United States…a country that somehow held his interest. Six years after his death, his nephew, Henry James Hungerford, indeed died without children, and on July 1, 1836, the United States Congress authorized acceptance of Smithson’s gift. President Andrew Jackson sent diplomat Richard Rush to England to negotiate for transfer of the funds, and two years later Rush set sail for home with 11 boxes containing a total of 104,960 gold sovereigns, 8 shillings, and 7 pence, as well as Smithson’s mineral collection, library, scientific notes, and personal effects. After the gold was melted down, it amounted to a fortune worth well over $500,000.

The money was sent to the United States with Smithson’s instructions for its use. It might have seemed like a simple request at the time of the will’s writing, but in the end, the money would sit in the bank waiting for a decade. The reason…a debate on how to use the money. Apparently, even though instructions for the money’s use were given, they did leave a few of the details up to the United States government. Finally, on this day August 10, 1846 James K Polk signed the Smithsonian Institution Act into law. After considering a series of recommendations, including the creation of a national university, a public library, or an astronomical observatory, Congress agreed that the bequest would support the creation of a museum, a library, and a program of research, publication, and collection in the sciences, arts, and history.

Today, the Smithsonian is composed of 19 museums and galleries including the recently announced National Museum of African American History and Culture, nine research facilities throughout the United States and the world, and the national zoo. Besides the original Smithsonian Institution Building, popularly known as the  Castle, visitors to Washington DC, tour the National Museum of Natural History, which houses the natural science collections, the National Zoological Park, and the National Portrait Gallery. The National Museum of American History houses the original Star-Spangled Banner and other artifacts of United States history. The National Air and Space Museum has the distinction of being the most visited museum in the world, exhibiting such marvels of aviation and space history as the Wright brothers’ plane and Freedom 7, the space capsule that took the first American into space. John Smithson, the Smithsonian Institution’s great benefactor, is interred in a tomb in the Smithsonian Building. It has been a pretty amazing use of that money. I think James Smithson would be pleased.

Castle, visitors to Washington DC, tour the National Museum of Natural History, which houses the natural science collections, the National Zoological Park, and the National Portrait Gallery. The National Museum of American History houses the original Star-Spangled Banner and other artifacts of United States history. The National Air and Space Museum has the distinction of being the most visited museum in the world, exhibiting such marvels of aviation and space history as the Wright brothers’ plane and Freedom 7, the space capsule that took the first American into space. John Smithson, the Smithsonian Institution’s great benefactor, is interred in a tomb in the Smithsonian Building. It has been a pretty amazing use of that money. I think James Smithson would be pleased.

Over the centuries of life on Earth, there have been numerous wars, and numerous weapons of warfare. Yet, few could bring fear to the heart of an infantryman quicker than the Flammenwerfer. Developed by the Germans during World War I, the Flammenwerfer…or Flamethrower, in English…once lit could throw a steady stream of flames 20 to 30 feet in front of it. For the men on the ground, this meant one of two things. They could run…abandoning the relative safety of their foxhole, usually with the result of being shot down by the enemy, or they could stand their ground and be incinerated. It wasn’t much of a choice really, and most ran in the hope of escaping the machine gun fire that would undoubtedly follow the flamethrower. It was a situation of instant death…no matter which choice a soldier made…not to mention the fact that every fiber of a soldier’s being and training told them to stand their ground. This weapon took much of it toll on the soldier’s sense of bravery.

Over the centuries of life on Earth, there have been numerous wars, and numerous weapons of warfare. Yet, few could bring fear to the heart of an infantryman quicker than the Flammenwerfer. Developed by the Germans during World War I, the Flammenwerfer…or Flamethrower, in English…once lit could throw a steady stream of flames 20 to 30 feet in front of it. For the men on the ground, this meant one of two things. They could run…abandoning the relative safety of their foxhole, usually with the result of being shot down by the enemy, or they could stand their ground and be incinerated. It wasn’t much of a choice really, and most ran in the hope of escaping the machine gun fire that would undoubtedly follow the flamethrower. It was a situation of instant death…no matter which choice a soldier made…not to mention the fact that every fiber of a soldier’s being and training told them to stand their ground. This weapon took much of it toll on the soldier’s sense of bravery.

The Flammenwerfer was developed in 1915 by the Germans, and first used in battle against the Allied forces on this day, July 30, 1915 at the Battle of Hooge. Eleven days before that battle, British infantry had captured the German occupied village of Hooge, located near Ypres in Belgium, by detonating a large mine. Using the flamethrowers, along with machine guns, trench mortars and hand grenades, the Germans got their positions  back on July 30, 1915. They broke through enemy front lines with ease, pushing the British forces back to their second trench. Only a few men were lost to actual burns, but a British officer was heard to explain that the weapons had a great demoralizing effect, and when added to the assault of the other powerful weapons, they proved mercilessly efficient at Hooge. I suppose that is true. I can think of few things more demoralizing for a soldier than running from your position in fear. Soldiers don’t take kindly to fear…or running away.

back on July 30, 1915. They broke through enemy front lines with ease, pushing the British forces back to their second trench. Only a few men were lost to actual burns, but a British officer was heard to explain that the weapons had a great demoralizing effect, and when added to the assault of the other powerful weapons, they proved mercilessly efficient at Hooge. I suppose that is true. I can think of few things more demoralizing for a soldier than running from your position in fear. Soldiers don’t take kindly to fear…or running away.

During World War I, the Germans were the only ones to use such a weapon, and not because it was difficult to make. So, why didn’t the Allies us it too? It was one of the great puzzles that emerged from World War I. Why? The British made three attempts with larger, more unwieldy prototypes: the smallest one was equal in size to the German Grof, which the enemy had almost abandoned by 1916. The French were more persistent, and by 1918 had at least seven companies trained in using flamethrowers, and still the use of the weapon never progressed to the same level as that of the German army.

By World War II, however, the flamethrower was the most dramatic hand weapon used by any Army and the most effective for its purpose. But it was during the 20th century that engineers and scientists placed flames  under advanced technological control in an effort to make flamethrowers portable, reliable and reasonably safe…for the user anyway. Prior to that the words “friendly fire” had a second meaning in that flamethrowers could kill the operator while he was doing his best to kill the enemy with it. The result of this new technology was a device with as much psychological impact as it’s lethality impact. That was the chief reason why the United States, Great Britain and other world powers used the flamethrower from World War I through the Vietnam War. Even today, Russia still has flamethrowers in its inventory. I guess it is an important weapon, but for most of us, I think that just the thought of using it on someone would make us seriously ill.

under advanced technological control in an effort to make flamethrowers portable, reliable and reasonably safe…for the user anyway. Prior to that the words “friendly fire” had a second meaning in that flamethrowers could kill the operator while he was doing his best to kill the enemy with it. The result of this new technology was a device with as much psychological impact as it’s lethality impact. That was the chief reason why the United States, Great Britain and other world powers used the flamethrower from World War I through the Vietnam War. Even today, Russia still has flamethrowers in its inventory. I guess it is an important weapon, but for most of us, I think that just the thought of using it on someone would make us seriously ill.

I suppose a true World War II history buff might know about some of the strange war stories there are out there, and I rather thought I was becoming a World War II history buff, but I had never heard of the Japanese Balloon Bombs. I can’t imagine how a nation could send a random bomb over another nation, not knowing where it will land, or who it will kill…but then, the evil we have seen in the 21st century has proven to be very much the same. I guess there really is nothing new under the sun. Where evil exists, horrible things happen. Such was the case with the Japanese Balloon Bombs. The Japanese were an evil nation at that time, and they didn’t care who they hurt. in 1945, a Japanese Balloon Bomb landed in rural Oregon, ad killed six people . As it turns out, these were the only World War II combat casualties within the continental 48 states. Apparently, the accuracy of the balloon bombs left something to be desired…thankfully.

I suppose a true World War II history buff might know about some of the strange war stories there are out there, and I rather thought I was becoming a World War II history buff, but I had never heard of the Japanese Balloon Bombs. I can’t imagine how a nation could send a random bomb over another nation, not knowing where it will land, or who it will kill…but then, the evil we have seen in the 21st century has proven to be very much the same. I guess there really is nothing new under the sun. Where evil exists, horrible things happen. Such was the case with the Japanese Balloon Bombs. The Japanese were an evil nation at that time, and they didn’t care who they hurt. in 1945, a Japanese Balloon Bomb landed in rural Oregon, ad killed six people . As it turns out, these were the only World War II combat casualties within the continental 48 states. Apparently, the accuracy of the balloon bombs left something to be desired…thankfully.

The idea of a balloon bomb was to send in a bomb that was silent. The problem is that balloons are hard to control. They go with the flow of the wind currents, so you don’t know where they will land. Then again, the Japanese were at war with the world, so they really didn’t care where the balloons would land. The six people who were killed by the Fu-Go or fire-balloon bomb, as they were called, were a Sunday School teacher Elyse Mitchell (and her unborn child), her 13 and 14 year old students, Jay Gifford, Edward Engen, Sherman Shoemaker, Dick Patzke, all of whom were killed instantly, when the bomb exploded. Dick Patzke’s sister, Joan was severely burned, and died moments later. The group had stopped for a moment, because Elyse Mitchell was feeling ill, and while her husband, Reverend Archie Mitchell talked with construction workers in the area, the six victims went to investigate a balloon they saw. It would prove to be a fatal mistake. The group had been going on a Saturday afternoon picnic near Klamath Falls, Oregon. They had only walked about 100 yards from the car. One of the road-crew workers, Richard Barnhouse, said “There was a terrible explosion. Twigs flew through the air, pine needles began to fall, dead branches and dust, and dead logs went up.”

Made of rubberized silk or paper, each balloon was about 33 feet in diameter. Barometer-operated valves released hydrogen if the balloon gained too much altitude or dropped sandbags if it flew too low. The balloons were filled with 19,000 cubic feet of hydrogen and the jet stream drew them eastward. They were designed to travel across the Pacific to North America, where they would drop incendiary devices or anti-personnel explosives. I would think the hydrogen alone would make a horrible bomb, but attached to the  balloon was the actual bomb. The Japanese released an estimated 9,000 fire balloons during the last months of World War II. At least 342 reached the United States, with some drifting as far as Nebraska. Some were shot down. Some caused minor damage when they landed, but no injuries. One hit a power line and blacked out the nuclear-weapons plant at Hanford, Washington. But the only known casualties from the 9,000 balloons…and the only combat deaths from any cause on the U S mainland were the five kids and their Sunday school teacher going to a picnic. What a valiant victory for the Japanese that was.

balloon was the actual bomb. The Japanese released an estimated 9,000 fire balloons during the last months of World War II. At least 342 reached the United States, with some drifting as far as Nebraska. Some were shot down. Some caused minor damage when they landed, but no injuries. One hit a power line and blacked out the nuclear-weapons plant at Hanford, Washington. But the only known casualties from the 9,000 balloons…and the only combat deaths from any cause on the U S mainland were the five kids and their Sunday school teacher going to a picnic. What a valiant victory for the Japanese that was.