train

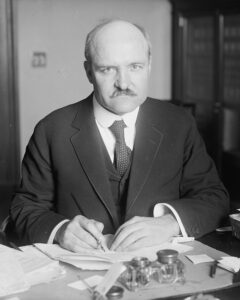

No matter what your opinion is on the use of Daylight Savings Time and Standard Time, the was originally a good reason for it, and that reason still applies today in many ways. The Standard Time Act of 1918, which was also known as the Calder Act (after the senator who sponsored the bill…William M. Calder), was the first United States federal law implementing Standard time and Daylight Saving Time in the United States. Prior to the Calder Act, the railroads had instituted time zones so that the rail schedule could have much needed consistency. Before time zones, no one had any idea when the train was due. It was a big mess. The Time Zone system defined five time zones for the United States and authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to define the limits of each time zone.

No matter what your opinion is on the use of Daylight Savings Time and Standard Time, the was originally a good reason for it, and that reason still applies today in many ways. The Standard Time Act of 1918, which was also known as the Calder Act (after the senator who sponsored the bill…William M. Calder), was the first United States federal law implementing Standard time and Daylight Saving Time in the United States. Prior to the Calder Act, the railroads had instituted time zones so that the rail schedule could have much needed consistency. Before time zones, no one had any idea when the train was due. It was a big mess. The Time Zone system defined five time zones for the United States and authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to define the limits of each time zone.

When the need for Daylight Savings Time came up, the original point of it was to save fuel by setting working hours so they coincided with the hours of natural daylight. While many people may not like that much, I think that a sensible person  can at least see the purpose of it. The act included a section that talked about the repeal of the change in one year, but in the end, it was decided that it was necessary to continue the practice. In fact, they could see no usefulness in repealing it, because the fuel savings had not changed. So, the practice has continued to this day. The Calder Act came about in answer to the European countries, who were already using the practice successfully.

can at least see the purpose of it. The act included a section that talked about the repeal of the change in one year, but in the end, it was decided that it was necessary to continue the practice. In fact, they could see no usefulness in repealing it, because the fuel savings had not changed. So, the practice has continued to this day. The Calder Act came about in answer to the European countries, who were already using the practice successfully.

Those who dislike the practice have been trying to repeal the act for as long as I can remember anyway, and with no success. I suppose that someday, they may succeed, but I’m not sure they will find that life without the time changes will be as amazing as they think. The sun will continue to make its  seasonal adjustments, and without the time changes, we will at some point, find ourselves wishing for another hour of daylight. The first time change to Daylight Saving Time took place on March 19, 1918, and it has been in practice since that time. I, personally, look forward to Daylight Saving Time every year. The longer days and more light make me feel happy, and I find that the few days or a week of adjustment is of little consequence in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, I’m sure I’ll hear lots of differing opinions from my readers. This year, Daylight Saving Time started on March 12, and Standard Time will begin on November 5…just so you know.

seasonal adjustments, and without the time changes, we will at some point, find ourselves wishing for another hour of daylight. The first time change to Daylight Saving Time took place on March 19, 1918, and it has been in practice since that time. I, personally, look forward to Daylight Saving Time every year. The longer days and more light make me feel happy, and I find that the few days or a week of adjustment is of little consequence in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, I’m sure I’ll hear lots of differing opinions from my readers. This year, Daylight Saving Time started on March 12, and Standard Time will begin on November 5…just so you know.

Jessie Earl, who was born in Crawfordville, Indiana on April 22, 1887 to John and Amanda (Tracy) Earl, was a very resourceful, and brave girl, although not many people would have known that had she not found herself in the situation she did on a Monday in December, 1901. School was over for the day, and Jessie was walking home. Her family was living in Advance, Indiana then, which was a small town about 15 miles west of Crawfordsville. Jessie’s walk took her beside the train tracks for a about a mile.

Jessie Earl, who was born in Crawfordville, Indiana on April 22, 1887 to John and Amanda (Tracy) Earl, was a very resourceful, and brave girl, although not many people would have known that had she not found herself in the situation she did on a Monday in December, 1901. School was over for the day, and Jessie was walking home. Her family was living in Advance, Indiana then, which was a small town about 15 miles west of Crawfordsville. Jessie’s walk took her beside the train tracks for a about a mile.

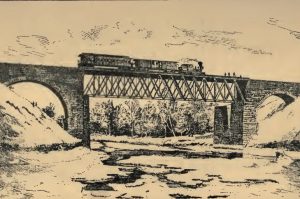

As Jessie was walking along she saw that the railroad trestle she passed every day was on fire. She immediately headed to find someone to warn, but at that moment she heard the train whistle. She knew she was out of time, and she would have to save the train herself. I can’t imagine a girl of just 13 years having the courage to do what she did next. The train, Chicago and Southwestern Railroad’s east-bound passenger train, was headed for serious danger, and no one knew what was happening…except a 13 year old girl. Jessie, however, was no ordinary girl.

She saw that the train was headed toward the burning trestle at full speed. By the time they saw the fire, it would be too late to stop the train. Jessie immediately dropped her basket and rushed down the track toward the train, running as fast as she could. She started waving her apron, to attract the attention of the engineer, who upon seeing the little girl, brought the train to a safe stop. I’m sure that his first thought was, “What is this crazy girl doing?” Nevertheless, he made the quick decision to stop to find out what the emergency was.

Upon inspection, the crew found that the burning trestle would never have held the weight of the train, and the resulting crash and derailment would have been catastrophic for the passengers and crew. When they saw what Jessie had saved them from, the crew and passengers almost smothered the little girl with congratulations for her brave act and gave her many mementoes as rewards for saving the train from plunging into the creek, 30 feet below. Of course, like most heroes, Jessie just thought she had done what any other person would do.  Still, you never know. We have all witnessed people walking right by a person lying on the ground, or driving past the scene of an accident without lending aid, or worse yet, filming it on their smart phones to post on the internet. Of course, the internet didn’t exist then, but I like to think it wouldn’t have mattered to little Jessie Earl. I like to think that she would have done what she did either way, because Jessie Earl seems like a heroic kind of girl.

Still, you never know. We have all witnessed people walking right by a person lying on the ground, or driving past the scene of an accident without lending aid, or worse yet, filming it on their smart phones to post on the internet. Of course, the internet didn’t exist then, but I like to think it wouldn’t have mattered to little Jessie Earl. I like to think that she would have done what she did either way, because Jessie Earl seems like a heroic kind of girl.

Sadly, I don’t have a picture of Jessie Earl, but I learned that she married Howard Bratton, and they three children…Dorthea, James, and Opal who went on to give them children and grandchildren. I wonder if they know that their grandmother and great grandmother was a true hero. I wonder if Jessie’s children ever knew. I wouldn’t be surprised to find that they didn’t. Jessie passed away on February 15, 1940, in Muncie, Indiana. She was 52 years old.

My sister-in-law, Brenda Schulenberg is a woman who is determined to accomplish her goals and dreams. She doesn’t let anything get in the way of getting her daily steps in, whether it is bicycling steps or foot steps, she reaches her goal of 25,000 steps a day…every day. If that means she gets up at 4:00 am to get to work at 8:00 am, then she does. Nothing gets in the way of her step count. At night, if she has been traveling during the day, and is a little behind in her steps, she simply doesn’t sit down until she finishes the steps. That means walking around her house for as long as it takes. Any place can be a trail, as long as you have room to walk around. Trails aren’t always outside, and Brenda utilizes any space necessary to complete her daily steps.

My sister-in-law, Brenda Schulenberg is a woman who is determined to accomplish her goals and dreams. She doesn’t let anything get in the way of getting her daily steps in, whether it is bicycling steps or foot steps, she reaches her goal of 25,000 steps a day…every day. If that means she gets up at 4:00 am to get to work at 8:00 am, then she does. Nothing gets in the way of her step count. At night, if she has been traveling during the day, and is a little behind in her steps, she simply doesn’t sit down until she finishes the steps. That means walking around her house for as long as it takes. Any place can be a trail, as long as you have room to walk around. Trails aren’t always outside, and Brenda utilizes any space necessary to complete her daily steps.

Brenda spent much of her life overweight and really unhealthy, and while most people wouldn’t want me to talk about that part of their lives, Brenda uses that part of her life, and the transition she has made to be an inspiration to others. She has set another goal for herself…to reach out to other people who are where she was…to let them know that it is never too late to change your life for the better. Getting healthy and fit is just a step away. Yes, it will take many steps, but the first step is the most important, because without the first step, you remain an overweight, unhealthy, couch potato. Of course, that first step…must be taken every day, if you are going to have to succeed. Most people when they get to that place, where their weight is out of control, and they have become unhealthy, decide that because of this health problem or that health problem, it is simply impossible for them to lose weight and become healthy again. Brenda is proof positive that they can. All it takes is much determination and that first step.

These days, Brenda enjoys things like traveling…by plane, train, or automobile. These are things she really couldn’t do before she lost the weight. She was so limited. Now she travels to different areas around Wyoming

and Colorado to speak to others about her story. Sometimes, all it takes to get someone started on the road to better health, is to see that someone else made it. Getting started is so hard, especially when you feel like you will never make it, but when you see someone like Brenda, who has turned her whole life around, you begin to feel like you can do it too. And that is what inspires Brenda…helping other people to succeed. Today is Brenda’s birthday. Happy birthday Brenda!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

and Colorado to speak to others about her story. Sometimes, all it takes to get someone started on the road to better health, is to see that someone else made it. Getting started is so hard, especially when you feel like you will never make it, but when you see someone like Brenda, who has turned her whole life around, you begin to feel like you can do it too. And that is what inspires Brenda…helping other people to succeed. Today is Brenda’s birthday. Happy birthday Brenda!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

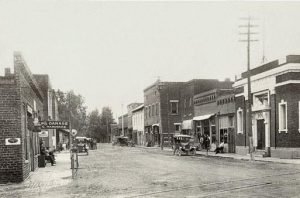

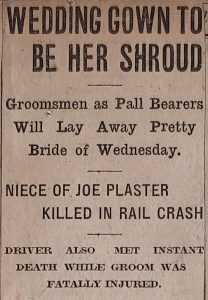

The headline read “Wedding Gown To Be Her Shroud.” The newspaper article was about a horrible tragedy, that took place just four days after the wedding of my husband, Bob’s 6th cousin 3 times removed, Ruth Schulenberg to Wilberd Youngman. The wedding took place on November 26, 1913, and was a large social affair for the smaller town of Tolono, Illinois, population of about 700, at the time. Ruth Schulenberg, was the daughter of Mr and Mrs Henry Schulenberg, and was a graduate of Saint Mary’s of the Wood where she was a member of a prominent sorority. Wilberd Youngman employed as a draughsman by the Burr Company of Champaign, Illinois. The wedding took place at Saint Patrick’s Catholic Church in Tolono.

The headline read “Wedding Gown To Be Her Shroud.” The newspaper article was about a horrible tragedy, that took place just four days after the wedding of my husband, Bob’s 6th cousin 3 times removed, Ruth Schulenberg to Wilberd Youngman. The wedding took place on November 26, 1913, and was a large social affair for the smaller town of Tolono, Illinois, population of about 700, at the time. Ruth Schulenberg, was the daughter of Mr and Mrs Henry Schulenberg, and was a graduate of Saint Mary’s of the Wood where she was a member of a prominent sorority. Wilberd Youngman employed as a draughsman by the Burr Company of Champaign, Illinois. The wedding took place at Saint Patrick’s Catholic Church in Tolono.

After their wedding, the young couple was on their honeymoon, in Kokomo, Indiana, where they had attended church at the Kokomo Catholic Church. Following the church service, they were on their way to a big wedding dinner in their honor at the country residence of a neighbor of Youngman’s cousin, Edward Grishaw, who was

transporting the couple in a closed carriage. As the carriage began its crossing of the tracks of the Lake Erie and Western Railway, Grishaw failed for look for trains, and pulled out in front of the Lake Erie train going full speed. The train ripped through the car, and by the time the train could stop and the crew reached the car’s occupants, Ruth Schulenberg and Edward Grishaw were dead. Wilberd Youngman was critically injured, and not expected to live.

transporting the couple in a closed carriage. As the carriage began its crossing of the tracks of the Lake Erie and Western Railway, Grishaw failed for look for trains, and pulled out in front of the Lake Erie train going full speed. The train ripped through the car, and by the time the train could stop and the crew reached the car’s occupants, Ruth Schulenberg and Edward Grishaw were dead. Wilberd Youngman was critically injured, and not expected to live.

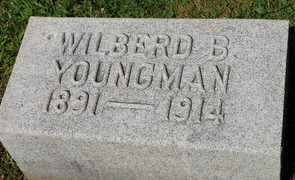

Amazingly, Wilberd Youngman did live…for eleven months. Youngman was taken to a hospital in Chicago, but his prognosis was grim. People just don’t come back from being hit by a train that ripped their car apart, and yet he was still alive, and actually recovering from his injuries…the visible injuries anyway. Youngman had lost so much that November day, and he was struggling to move forward. Ruth Schulenberg had been his soulmate, and his very best friend. She was the love of his life, and he knew there could never be another woman for him. Wilberd Youngman was not a man who would commit suicide, but he also could not recover from this deepest injury…the one that broke his heart. Slowly, over the eleven months that followed the saddest day of  his life, Wilberd Youngman dwindled away. it wasn’t a refusal of food and water, but rather a refusal to go on without his precious Ruth. Finally, on October 24, 1914, just short of 11 months after that awful day…November 30, 1913, Wilberd Youngman could no longer go on living, and so, with his parents by his side, he simply passed away. The final cause of death was listed as a broken heart. That, to me was the saddest cause of death I had ever heard. Because of the loss of his wife, Wilberd simply had no desire to live either. He tried to recover…physically, but his heart was no longer in it, and he finally just gave up and quit trying. The Honeymoon Tragedy had finally claimed it’s last victim.

his life, Wilberd Youngman dwindled away. it wasn’t a refusal of food and water, but rather a refusal to go on without his precious Ruth. Finally, on October 24, 1914, just short of 11 months after that awful day…November 30, 1913, Wilberd Youngman could no longer go on living, and so, with his parents by his side, he simply passed away. The final cause of death was listed as a broken heart. That, to me was the saddest cause of death I had ever heard. Because of the loss of his wife, Wilberd simply had no desire to live either. He tried to recover…physically, but his heart was no longer in it, and he finally just gave up and quit trying. The Honeymoon Tragedy had finally claimed it’s last victim.

About 47 years ago, while on a family vacation to California, my brother-in-law, Ron Schulenberg decided that he wanted to stay in California, and when asked what they should do about his older brother, Bob, Ron said,”just send for him in the mail.” Unfortunately, Ron was a little late in history for his cool little idea. You see, while the mailing of children was a practice between 1913 and 1920, Ron was living in the year 1971. Nevertheless, while Ron’s idea was workable, he cannot be credited with the original idea.

About 47 years ago, while on a family vacation to California, my brother-in-law, Ron Schulenberg decided that he wanted to stay in California, and when asked what they should do about his older brother, Bob, Ron said,”just send for him in the mail.” Unfortunately, Ron was a little late in history for his cool little idea. You see, while the mailing of children was a practice between 1913 and 1920, Ron was living in the year 1971. Nevertheless, while Ron’s idea was workable, he cannot be credited with the original idea.

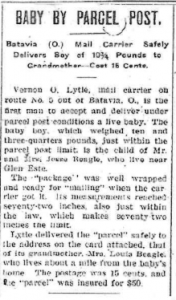

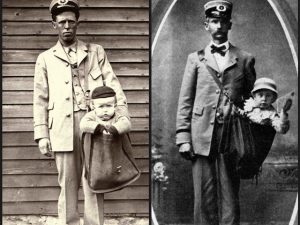

When the Post Office’s Parcel Post service officially began on January 1, 1913, the new service suddenly allowed millions of Americans access to all kinds of goods and services. That was a great thing, but as is often the case, it almost immediately had some unintended consequences. Believe it or not, some parents decided to send their children through the mail. Just a few weeks after Parcel Post began, an Ohio couple named Jesse and Mathilda Beagle “mailed” their 8-month-old son James to his grandmother, who lived just a few miles away in Batavia. It seems that Baby James was just under the 11-pound weight limit for packages sent via Parcel Post, and his “delivery” cost his parents only 15 cents in postage. Of course, being the “responsible parents” they were, they did insure him for $50. As you can imagine, this “delivery” made the newspapers very quickly. While you might have thought about the outrage that would have come from such an action these days, it did not. In fact, for the next several years, similar stories would occasionally surface as other parents followed suit. One famous case, on February 19, 1914, was that of a four year old girl named Charlotte May Pierstorff was “mailed” via train from her home in Grangeville, Idaho to her grandparents’ house about 73 miles away. Nancy Pope, who wrote for the National Postal Museum wrote the story, which became so legendary, that it was even made into a children’s book, Mailing May. Luckily, little May wasn’t unceremoniously shoved into a canvas sack along with the other packages. As it turns out, she was accompanied on her trip by her mother’s cousin, who worked as a clerk for the railway mail service, according to United States Postal Service historian Jenny Lynch. It’s likely that his influence (and his willingness to chaperone his young cousin) is what convinced local officials to send the little girl along with the mail.

In the next few years, stories about children being mailed through rural routes would crop up from time to time as people pushed the limits of what could be sent through Parcel Post. The reason being that postage was cheaper than a train ticket. One of the most overlooked, yet most significant innovations of the early 20th century might be the Post Office’s decision to start shipping large parcels and packages through the mail. While private delivery companies flourished during the 19th century, the Parcel Post dramatically expanded the reach of mail-order companies to America’s many rural communities, as well as the demand for their products. Over the years, these stories continued to surface from time to time as parents occasionally managed to slip their children through the mail thanks to rural workers willing to let it slide. Finally, on June 14, 1913, several newspapers including the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times all ran stories stating the the postmaster had officially decreed that children could no longer be sent through the mail. But while this announcement seems to have stemmed the trickle of tots traveling via post, Lynch says the story wasn’t entirely accurate. Soon, it became obvious that this bizarre practice had to be stopped, and on June 13, 1920, notice was given that the Post Office would no longer let children be sent through the mail. While child

mailing stopped, there was a time when “Mail carriers were trusted servants, and that goes to prove it. There are stories of rural carriers delivering babies and taking care of the sick. Even now, they’ll save lives because they’re sometimes the only persons that visit a remote household every day.” Still, I don’t think I would mail my child somewhere. Thankfully, there are more travel options for children these days than pinning some postage to their shirts and sending them off with the mailman.

mailing stopped, there was a time when “Mail carriers were trusted servants, and that goes to prove it. There are stories of rural carriers delivering babies and taking care of the sick. Even now, they’ll save lives because they’re sometimes the only persons that visit a remote household every day.” Still, I don’t think I would mail my child somewhere. Thankfully, there are more travel options for children these days than pinning some postage to their shirts and sending them off with the mailman.

A sudden downpour near Terry, Montana on the evening of June 19, 1938 caused a flash flooding of the Custer Creek that would lead to a disaster before the night was over. Earlier in the day, a track walker was sent out the check the rail lines near Custer Creek which was located near the town of Terry, Montana. After his inspection, he reported to his superiors that the conditions were dry, and there were no problems with the tracks.

A sudden downpour near Terry, Montana on the evening of June 19, 1938 caused a flash flooding of the Custer Creek that would lead to a disaster before the night was over. Earlier in the day, a track walker was sent out the check the rail lines near Custer Creek which was located near the town of Terry, Montana. After his inspection, he reported to his superiors that the conditions were dry, and there were no problems with the tracks.

That was true at the time, but within a few hours, a sudden downpour overwhelmed Custer Creek. A small winding river, Custer Creek runs through 25 miles of the Great Plains before depositing into the Yellowstone River. Small streams like Custer Creek are prone to flash floods, because they don’t have  the capacity to handle any big influx of water, and their banks can quickly and easily be overtaken during heavy rains. As the water came rushing down stream, it washed out a bridge used by the trains. When the Olympian Special came through, it went crashing into the raging waters with no warning. Two sleeper cars were buried in the muddy waters. The night was pitch black seriously hampering rescue efforts. In all, 46 people lost their lives, and 60 others were seriously injured. The rear cars stayed above the water, but scores of passengers were seriously injured. They could not be evacuated until the following morning. I can’t even begin to imagine how awful that was.

the capacity to handle any big influx of water, and their banks can quickly and easily be overtaken during heavy rains. As the water came rushing down stream, it washed out a bridge used by the trains. When the Olympian Special came through, it went crashing into the raging waters with no warning. Two sleeper cars were buried in the muddy waters. The night was pitch black seriously hampering rescue efforts. In all, 46 people lost their lives, and 60 others were seriously injured. The rear cars stayed above the water, but scores of passengers were seriously injured. They could not be evacuated until the following morning. I can’t even begin to imagine how awful that was.

That was a tough week for Montana. Just a few days later, Black Eagle saw “torrents of water” that floated  furniture in the house of Sam Tadich, the sheriff had to help a rescue effort, the road to Giant Springs washed away and water was up to cows’ flanks around the Sun River. Havre’s worst flood came in June 22, 1938, when a cloudburst in the Bear Paw Mountains sent out a wall of water. Ten people were killed. Floating train cars were wedged under the viaduct, 10 miles of highway were underwater between Laredo and Box Elder, with a bridge washed out, the Havre Daily News reported. Rain is a good thing, but too much rain, coming too fast can devastate an area, especially one with a creek or river, in a very short time, and for Montana, it was a very rainy week, making it a very tough week.

furniture in the house of Sam Tadich, the sheriff had to help a rescue effort, the road to Giant Springs washed away and water was up to cows’ flanks around the Sun River. Havre’s worst flood came in June 22, 1938, when a cloudburst in the Bear Paw Mountains sent out a wall of water. Ten people were killed. Floating train cars were wedged under the viaduct, 10 miles of highway were underwater between Laredo and Box Elder, with a bridge washed out, the Havre Daily News reported. Rain is a good thing, but too much rain, coming too fast can devastate an area, especially one with a creek or river, in a very short time, and for Montana, it was a very rainy week, making it a very tough week.

The Schienenzeppelin or rail zeppelin was an experimental railcar which resembled the Zeppelin airship. It was designed by the German aircraft engineer Franz Kruckenberg in 1929. The Schienenzeppelin was powered by a propeller located at the rear. The railcar accelerated to 143 mph setting the land speed record for a petroleum powered rail vehicle. Only one Schienenzeppelin was ever built due to safety concerns. It was never really put into service and was finally dismantled in 1939. The propeller, which powered the railcar, was also the source of concern for its safety. It was exposed, and so the concern was that someone might be hit by he propeller.

The Schienenzeppelin or rail zeppelin was an experimental railcar which resembled the Zeppelin airship. It was designed by the German aircraft engineer Franz Kruckenberg in 1929. The Schienenzeppelin was powered by a propeller located at the rear. The railcar accelerated to 143 mph setting the land speed record for a petroleum powered rail vehicle. Only one Schienenzeppelin was ever built due to safety concerns. It was never really put into service and was finally dismantled in 1939. The propeller, which powered the railcar, was also the source of concern for its safety. It was exposed, and so the concern was that someone might be hit by he propeller.

Anticipating the design of the Schienenzeppelin, the earlier Aerowagon, an experimental Russian high-speed railcar, was also equipped with an aircraft engine and a propeller. On 24 July 1921, a group of delegates to the First Congress of the Profintern, led by Fyodor Sergeyev, took the Aerowagon from Moscow to the Tula collieries to test it. Abakovsky was also on board. Although they successfully arrived in Tula on their maiden run, the return route to Moscow was not successful. The Aerowagon derailed at high speed near Serpukhov, killing six of the 22 people on board. A seventh man later died of his injuries.

The Schienenzeppelin railcar was built at the beginning of 1930 in the Hannover-Leinhausen works of the German Imperial Railway Company. The work was completed by Fall of that year. The vehicle was 84 feet 9 3/4 inches long and had just two axles, with a wheelbase of 64 feet 3 5/8  inches. The height was 9 feet 2 1/4 inches. It had two conjoined BMW IV 6-cylinder petroleum aircraft engines. The driveshaft was raised seven-degrees above the horizontal to give the vehicle some downwards thrust. The body of the Schienenzeppelin was streamlined, having some resemblance to the era’s popular Zeppelin airships, and it was built of aluminum in aircraft style to reduce weight. The railcar could carry up to 40 passengers. Its interior was designed in Bauhaus-style.

inches. The height was 9 feet 2 1/4 inches. It had two conjoined BMW IV 6-cylinder petroleum aircraft engines. The driveshaft was raised seven-degrees above the horizontal to give the vehicle some downwards thrust. The body of the Schienenzeppelin was streamlined, having some resemblance to the era’s popular Zeppelin airships, and it was built of aluminum in aircraft style to reduce weight. The railcar could carry up to 40 passengers. Its interior was designed in Bauhaus-style.

On May 10, 1931, the Schienenzeppelin exceeded a speed of 120 miles per hour for the first time. Afterwards, it toured Germany as an exhibit to the general public throughout Germany. There was still some concern due to the trains speed. On June 21, 1931, it set a new world railway speed record of 143 miles per hour on the Berlin–Hamburg line between Karstädt and Dergenthin, which was not surpassed by any other rail vehicle until 1954. The railcar still holds the land speed record for a petroleum powered rail vehicle. This high speed was attributable, in addition to other things, to its low weight, which was only 44800 pounds.

While several modifications were attempted, ultimately the Schienenzeppelin was scrapped. Due to many problems with the Schienenzeppelin prototype, the Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft decided to go their own way in developing a high-speed railcar, leading to the Fliegender Hamburger (Flying Hamburger) in 1933. This new design was much more suitable for regular service and served also as the basis for later railcar developments. However, many of the Kruckenberg ideas were based on the experiments with Schienenzeppelin and high-speed rail travel, found their way into later DRG railcar designs.

The failure, if it could be called that, of Schienenzeppelin has been attributed to everything from the dangers of  using an open propeller in crowded railway stations to fierce competition between Kruckenberg’s company and the Deutsche Reichsbahn’s separate efforts to build high-speed railcars. Another disadvantage of the rail zeppelin was the inability to pull additional wagons to form a train, because of its construction. Furthermore, the vehicle could not use its propeller to climb steep gradients, as the flow would separate when full power was applied. Thus an additional means of propulsion was needed for such circumstances. Safety concerns have been associated with running high-speed railcars on old track network, with the inadvisability of reversing the vehicle, and with operating a propeller close to passengers.

using an open propeller in crowded railway stations to fierce competition between Kruckenberg’s company and the Deutsche Reichsbahn’s separate efforts to build high-speed railcars. Another disadvantage of the rail zeppelin was the inability to pull additional wagons to form a train, because of its construction. Furthermore, the vehicle could not use its propeller to climb steep gradients, as the flow would separate when full power was applied. Thus an additional means of propulsion was needed for such circumstances. Safety concerns have been associated with running high-speed railcars on old track network, with the inadvisability of reversing the vehicle, and with operating a propeller close to passengers.

When we think of train robberies, most of us think of the Old West, and bandits on horseback, riding up along side the train, and jumping on. Then, with guns pointed at everyone, they robbed the train, and left the same way they came in. In fact, I think most of us thought that the days of robbing a train were over, and maybe that played to the advantage of the outlaws, because on August 8, 1963, a group of 15 thieves and 2 key informants pulled off one of the most famous heists of all time.

When we think of train robberies, most of us think of the Old West, and bandits on horseback, riding up along side the train, and jumping on. Then, with guns pointed at everyone, they robbed the train, and left the same way they came in. In fact, I think most of us thought that the days of robbing a train were over, and maybe that played to the advantage of the outlaws, because on August 8, 1963, a group of 15 thieves and 2 key informants pulled off one of the most famous heists of all time.

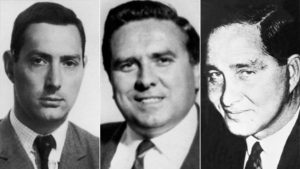

The leader and mastermind behind the heist was Bruce Reynolds, who was a known burglar and armed robber. He was an avid “fan” of the Wild West railroad heists in America, so he decided to see if he could pull something like that off in England. Reynolds and 14 other men wearing ski masks and helmets held up the Royal Mail train heading between Glasgow, Scotland, and London, England. The gang used Land Rover vehicles which had been stolen in central London and marked with identical license plates in order to confuse the police. Unlike the Wild West gangs, this gang used a false red signal to get the train to stop, then hit the driver with an iron bar, seriously injuring him, in order to gain control of the train. The thieves loaded 120 mailbags filled with the equivalent of $7 million in used bank notes into their Land Rovers and sped off to their hideout, which was the Leatherslade Farm in Buckinghamshire, England, to divide their loot. The robbers had cut all the telephone lines in the vicinity, but one of the rail-men left on the train at Sears Crossing caught a passing goods train to Cheddington, where he raised the alarm at around 04:20.

As often happens, the media reports on these things, and before you know it, they are viewed as folk heroes by the public for the audacious nature of their crime and their flight from justice. The first reports of the robbery were broadcast on the VHF police radio within a few minutes and this is where the gang heard the line “A robbery has been committed and you’ll never believe it – they’ve stolen the train!” I’m sure that added to the charm felt by the public, because seriously, who but an eccentric, would steal a train. As always seems to happen, 12 of the 15 robbers were eventually captured. They received a collective 300 years in prison. One of them, a small-time hood named Ronnie Biggs, escaped from prison after just 15 months and underwent plastic surgery to change his appearance. He fled the country and eluded capture for years, finally

giving himself up in 2001 when he returned from Brazil voluntarily to serve the 28 years remaining in his sentence…a rather odd thing to do, considering the fact that he had successfully escaped. The two Land Rovers used in the robbery were discovered at the thieves’ hideout. A car enthusiast still owns one of them today, and considers it a collector’s item.

giving himself up in 2001 when he returned from Brazil voluntarily to serve the 28 years remaining in his sentence…a rather odd thing to do, considering the fact that he had successfully escaped. The two Land Rovers used in the robbery were discovered at the thieves’ hideout. A car enthusiast still owns one of them today, and considers it a collector’s item.

Jonathan Luther “John” “Casey” Jones was born on March 14, 1863. As a boy, he lived near Cayce, Kentucky, which is where his nickname of “Cayce” came from, but he chose to spell it “Casey”. Jones went to work for the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and performed well and was promoted to brakeman on the Columbus, Kentucky to Jackson, Tennessee route, and then to fireman on the Jackson, Tennessee to Mobile, Alabama route. That caught my attention, because my grandfathers and other family members worked for the railroad too, but it was not working on the railroad that made Casey famous…at least not totally anyway. Casey always dreamed of being an engineer. He worked hard, but did receive nine citations for rule violations, and 145 total days suspended. In the year prior to his death, Jones had not been cited for any rules infractions. His dreams came true, but not in the way he expected. In the summer 1887, a yellow fever epidemic struck many train crews on the neighboring Illinois Central Railroad, providing an unexpected opportunity for faster promotion of firemen on that line. On March 1, 1888, Jones switched to the Illinois Central Railroad, taking a freight locomotive between Jackson, Tennessee and Water Valley, Mississippi.

Jonathan Luther “John” “Casey” Jones was born on March 14, 1863. As a boy, he lived near Cayce, Kentucky, which is where his nickname of “Cayce” came from, but he chose to spell it “Casey”. Jones went to work for the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and performed well and was promoted to brakeman on the Columbus, Kentucky to Jackson, Tennessee route, and then to fireman on the Jackson, Tennessee to Mobile, Alabama route. That caught my attention, because my grandfathers and other family members worked for the railroad too, but it was not working on the railroad that made Casey famous…at least not totally anyway. Casey always dreamed of being an engineer. He worked hard, but did receive nine citations for rule violations, and 145 total days suspended. In the year prior to his death, Jones had not been cited for any rules infractions. His dreams came true, but not in the way he expected. In the summer 1887, a yellow fever epidemic struck many train crews on the neighboring Illinois Central Railroad, providing an unexpected opportunity for faster promotion of firemen on that line. On March 1, 1888, Jones switched to the Illinois Central Railroad, taking a freight locomotive between Jackson, Tennessee and Water Valley, Mississippi.

Jones was a bit of a risk taker, but I doubt if some of the people who knew about some of his “risks” would hold that against him. A little-known example of Jones’ heroic act saved the life of a little girl. As Jones’ train approached Michigan City, Mississippi, he had walked out on the running board to oil the relief valves. He had finished well before they arrived at the station, as planned, and was returning to the cab when he noticed a group of small children dart in front of the train some 60 yards ahead. They all cleared the rails easily except for a little girl who suddenly froze in fear at the sight of the oncoming iron horse. Jones shouted to Stevenson to reverse the train and yelled to the girl to get off the tracks in almost the same breath. Then he realize that she was frozen in fear. He raced to the tip of the cowcatcher and braced himself on it, reaching out as far as he could to pull the frightened but unharmed girl from the rails.

On April 30, 1900, while Casey was running the Cannonball Express, and trying to make up for a late start, it would be his heroics that would cost him his life. As Casey was coming into Vaughan, Mississippi, he did not know that three separate trains were in the station at Vaughan…double-header freight train No. 83 and long freight train No. 72 were both in the passing track to the east of the main line. As the combined length of the trains was ten cars longer than the length of the east passing track, some of the cars were stopped on the main line. The two sections of northbound local passenger train No. 26 had arrived from Canton earlier, and required a “saw by” for them to get to the “house track” west of the main line. The “saw by” maneuver required that No. 83 back up (onto the main line) to allow No. 72 to move northward and pull its overlapping cars off the main line and onto the east side track from the south switch, thus allowing the two sections of No. 26 to gain access to the west house track. The “saw by”, however, left the rear cars of No. 83 overlapping above the north switch and on the main line…right in Jones’ path. As workers prepared a second “saw by” to let Jones pass, an air hose broke on No. 72, locking its brakes and leaving the last four cars of No. 83 on the main line.

Jones was almost back on schedule, running at about 75 miles per hour toward Vaughan, and traveling through a 1.5 mile left-hand curve that blocked his view. Webb’s view from the left side of the train was better, and he was first to see the red lights of the caboose on the main line. “Oh my Lord, there’s something on the main line!” he yelled to Jones. Jones quickly yelled back “Jump Sim, jump!” to Webb, who crouched down and jumped from the train, about 300 feet before impact, and knocked unconscious by his fall. The last thing Webb heard as he jumped was the long, piercing scream of the whistle as Jones warned anyone still in the freight train looming ahead. He was only two minutes behind schedule. Jones reversed the throttle and slammed the airbrakes into  emergency stop, but “Ole 382” quickly plowed through a wooden caboose, a car load of hay, another of corn, and halfway through a car of timber before leaving the track. He had reduced his speed from about 75 miles per hour to about 35 miles per hour when he hit. Because Jones stayed on board to slow the train, he saved the passengers from serious injury and death. He was the only fatality of the collision. His watch stopped at the time of impact…3:52 am on April 30, 1900. Legend holds that when his body was pulled from the wreckage, his hands still clutched the whistle cord and brake. A stretcher was brought from the baggage car on No. 1, and crewmen of the other trains carried his body to the depot, a half-mile away.

emergency stop, but “Ole 382” quickly plowed through a wooden caboose, a car load of hay, another of corn, and halfway through a car of timber before leaving the track. He had reduced his speed from about 75 miles per hour to about 35 miles per hour when he hit. Because Jones stayed on board to slow the train, he saved the passengers from serious injury and death. He was the only fatality of the collision. His watch stopped at the time of impact…3:52 am on April 30, 1900. Legend holds that when his body was pulled from the wreckage, his hands still clutched the whistle cord and brake. A stretcher was brought from the baggage car on No. 1, and crewmen of the other trains carried his body to the depot, a half-mile away.

Through the centuries, new designs were developed to build things we needed. As the railroad moved across the nation, track laying came across deep gorges and flat plains. Of course, the flat plains were easy to deal with, and trains could simply go around any hills in the area, but the rivers and gullies were a bigger problem. They needed bridges, and so Charles Collins and Amasa Stone jointly designed a bridge to be used at Ashtabula, Ohio. It was the first Howe-type wrought iron truss bridge built. Collins was worried about the bridge, thinking that it was “too experimental” and needed further evaluation. Nevertheless, higher powers prevailed, and the bridge was built. Collins had been right to be concerned. The bridge lasted just 11 years before it collapsed.

Through the centuries, new designs were developed to build things we needed. As the railroad moved across the nation, track laying came across deep gorges and flat plains. Of course, the flat plains were easy to deal with, and trains could simply go around any hills in the area, but the rivers and gullies were a bigger problem. They needed bridges, and so Charles Collins and Amasa Stone jointly designed a bridge to be used at Ashtabula, Ohio. It was the first Howe-type wrought iron truss bridge built. Collins was worried about the bridge, thinking that it was “too experimental” and needed further evaluation. Nevertheless, higher powers prevailed, and the bridge was built. Collins had been right to be concerned. The bridge lasted just 11 years before it collapsed.

On December 28, 1876, a Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway train…the Pacific Express left New York. It struggled along through the drifts and the blinding storm. The train was pulling into Ashtabula, Ohio, shortly before 8:00pm on December 29, 1876, several hours behind schedule. The eleven cars were a heavy burden to the two engines. The leading locomotive broke through the drifts beyond the ravine, and rolled on across the bridge at Ashtabula at less than ten miles an hour. The head lamp could barely be seen because the air was thick with the driving snow. The leading engine reached solid ground, and the engineer had just given it steam…when something in the undergearing of the bridge snapped.

What followed was a horror beyond horrors…not only for the victims, but for the rescuers as well…maybe even more so for the rescuers. As the bridge crumbled beneath the weight of the train, the train and its 159 passengers fell 70 feet into the river below. More than 90 people, passengers and crew, were killed when the train hit the river and ignited into a huge ball of flames. Only the lead engine escaped the fall. As the bridge fell, the engineer gave it a quick head of steam, which tore the draw head from its tender, and the liberated engine shot forward and buried itself in the snow. The engineer escaped with a broken leg. The proportions of the Ashtabula horror are still only approximately known. Daylight, brought with it the opportunity to find and count the saved. It also revealed the fact that two out of every three passengers on the train were lost. Of the 160 passengers who the injured conductor reports as having been on board, fifty nine were found or accounted for as surviving. The remaining 100, burned to ashes or shapeless lumps of charred flesh, were lying under the ruins of the bridge and train. Every possible element of horror was there. First came the crash of the bridge, the agonizing moments of suspense as the seven laden cars plunged down their fearful leap to the icy riverbed. Then the fire, that devoured all that had been left alive by the crash. The water that gurgled up from under the broken ice brought with it another form of death. And finally, the biting blast of freezing air filled with snow, that froze those who had escaped the water and fire.

For the rescuers, the horror had just begun. I can’t think of anything worse than seeing those bodies after they were horribly mangled, drowned, and burned…some beyond recognition, some completely cremated. The number of persons killed cannot be accurately stated, because it is not known exactly how many there were on the train. It is supposed that some of the bodies were entirely consumed in the flames, as well. The official list of those killed and those who have died of their injuries, gives the number as fifty five, but it is suspected to be somewhat higher. There is no death list to report…and in fact, there can be none. There are no remains that can ever be identified. The three charred, shapeless lumps recovered were burned beyond recognition. For the rest, there are piles of white ashes in which were found the crumbling particles of bones. In other places masses of black, charred debris, half under water, which may contain fragments of bodies, but nothing that resembled a human body. It is thought that there may have been a few corpses under the ice, as there were women and children who jumped into the water and sank, but none have been recovered. Periodically, as people began looking for people that were missing around the country, and they were able to place them, as possibly on the train, more supposed victims have been identified…at least there is the possibility that they were a victim.

The Ashtabula, Ohio Railroad Disaster, often referred to simply as the Ashtabula Disaster or the Ashtabula Horror, was one of the worst railroad disasters in American history. The event occurred just 100 yards from the railroad station at Ashtabula, Ohio. It’s topped only by the Great Train Wreck of 1918 in Nashville, Tennessee. Charles Collin, the chief engineer, who knew as few men did the defects of that bridge, but was powerless to repair them, had been listening for this very crash for years. Collins, locked himself in his bedroom and shot himself while the inquest was in progress rather than tell the world all he believed he knew. Collins was found  dead in his bedroom of a gunshot wound to the head. He had tendered his resignation to the Board of Directors the previous Monday. Collins was believed to have committed suicide out of grief and feeling partially responsible for the tragic accident, however, a police report at the time suggested the wound had not been self inflicted. Documents discovered in 2001 and an examination of Collins’ skull suggest that he had indeed been murdered. Amasa Stone committed suicide seven years later after experiencing financial difficulties with some foundries he had interests in, suffering from severe ulcers that kept him from sleeping, and scorn from the public over the disaster.

dead in his bedroom of a gunshot wound to the head. He had tendered his resignation to the Board of Directors the previous Monday. Collins was believed to have committed suicide out of grief and feeling partially responsible for the tragic accident, however, a police report at the time suggested the wound had not been self inflicted. Documents discovered in 2001 and an examination of Collins’ skull suggest that he had indeed been murdered. Amasa Stone committed suicide seven years later after experiencing financial difficulties with some foundries he had interests in, suffering from severe ulcers that kept him from sleeping, and scorn from the public over the disaster.