stunt double

We have all heard of stunt doubles. They are the people who make the shows we watch seem fearless as they perform their daring feats and even some that aren’t really so daring, but they just don’t want their actors scratched. Somehow these people, at least at a distance look just like the actor they are supposed to be. Sometimes they are very close, as in the case of brothers, David Paul Olsen, who is the stunt double for his brother, Eric Christian Olsen on NCIS Los Angeles. They aren’t twins, but the brothers loo enough alike to pull it off during filming.

We have all heard of stunt doubles. They are the people who make the shows we watch seem fearless as they perform their daring feats and even some that aren’t really so daring, but they just don’t want their actors scratched. Somehow these people, at least at a distance look just like the actor they are supposed to be. Sometimes they are very close, as in the case of brothers, David Paul Olsen, who is the stunt double for his brother, Eric Christian Olsen on NCIS Los Angeles. They aren’t twins, but the brothers loo enough alike to pull it off during filming.

While this is common, there is another type of “double” that is just as often used and is much less known. Government officials such as presidents, kings, and even congress or parliament members have been known to use doubles so that they can travel safely without worrying about being assassinated. Strangely, these doubles are very often denied. We are told that we are imagining things, but when we take a moment to look closely, the differences are obvious. This has gone on throughout history, although probably not as easily as the more recent history.

Sometimes the double goes to extremes, such as plastic surgery, but my guess is that with the more recent ability to make life-like masks, the need for such extreme measures has lessened. Still, anyone who is awake knows that doubles are and likely will always be used to protect or hide that elites who feel the need to move in relative anonymity. The possibilities are endless really. Having a double could mask a death of a high ranking official, such as, it has been believed, Kim Jong-Un, who has been seen looking heavy and then a short time later, thinner, when it would be impossible for him to have lost the weight so quickly. They can deny it all they want to, but when you look at things that are harder to change, like ear lobes, chins, and even teeth that seem to go back and forth from chipped to not chipped. No body double or stunt double is going to be a perfect match, even with plastic surgery. Facial shape and bone structure are going to have slight differences…even in  identical twins…which could be the easiest body double to use, if the twin is not the “important” person his or her sibling is. How awesome would that be to face up to? “Yes, I’m my brother’s body double, because I am expendable.” Right!! How wonderful would that feel for the non-important twin?

identical twins…which could be the easiest body double to use, if the twin is not the “important” person his or her sibling is. How awesome would that be to face up to? “Yes, I’m my brother’s body double, because I am expendable.” Right!! How wonderful would that feel for the non-important twin?

We can argue that some of our prominent politicians these days have body doubles, or we can “stick our heads in the sand” and believe that they don’t, but the reality is that if you look closely, you will see that they very likely do have a double. With the internet, and the multitude of pictures taken of a politician every day, it becomes more and more difficult to deny what is right there in front of our eyes. It up to us to decide to believe what we are told or search out the truth.

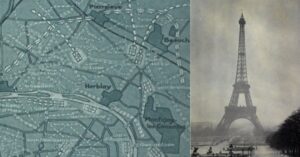

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

When you have a landmark city…a City of Lights, you want to protect it from the ravages of war. Paris was just that…the City of Lights, and during World War I, in an effort to protect the city from enemy bombs, the French built a “fake Paris” to the city’s immediate north. Complete with a duplicate Champs-Elysées and Gard Du Nord, this “dummy version” of Paris was built by the French towards the end of the war as a means of throwing off German bomber and fighter pilots flying over French skies. Wily military strategists, understandably tired of the enemy dropping bombs on their beautiful hometown, had decided that the best way to keep the city safe was to bring in a stunt double…a life-sized mock up situated to act as a decoy to draw fire from Paris proper.

London’s Daily Telegraph explains that the fake city wasn’t just “a bunch of cardboard cutouts.” No, far from it, in fact. There were “electric lights, replica buildings, and even a copy of the Gare du Nord—the station from which high-speed trains now travel to and from London.” The painters went so far as to use paint to create “the impression of dirty glass roofs of factories.” Fake trains and railroad tracks were lit up as well. There was a phony Champs-Elysées. Many of us today would say, “How could that work? The Germans must have known where they were dropping their bombs!” Nevertheless, it stands to reason that in the early 20th century, the plan could have worked. “Radar was in its infancy in 1918, and the long-range Gotha heavy bombers being used by the German Imperial Air Force were similarly primitive,” the Telegraph notes. “Their crew would hold bombs by the fins and then drop them on any target they could see during quick sorties over major cities like Paris and London.”

No one really knows how well the plan might have worked, because it was never put to the test. World War I ended before the fake city was finished. Both the real Paris and the fake one escaped significant damage. The fake version has long since been dismantled, though photos of it still remain. I suppose it was a ghost town of  it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

it’s own, and had it remained, it would have been interesting to visit and very likely a tourist attraction. Seriously…the idea of a to-scale decoy city made of wood and canvas dumped out in the leafy suburbs just a few miles from Paris’ instantly recognizable landscape may seem a little far fetched, if not completely crazy. Nevertheless, as the war progressed and French anti-aircraft technology improved, the daylight airship bombings which had previously caused such havoc were eventually rendered too risky for the planes. As such, any bombing raids were forced to take place under cover of darkness and it was at this point that an illuminated sham Paris began to…shall we say…shine!!

To further validate the idea, French fighter pilots reported that during night flights they looked for familiar features of the landscape below when attempting to locate Paris. According to their research, railways, lakes, rivers, roads and woodland were the most useful indicators that they were in the neighborhood. Using this information, the mastermind behind the replica project, Fernand Jacopozzi, along with his team of highly capable engineers worked to make life even harder for the German pilots who were already struggling to find their bearings in an era before radar or precision targeting. Intending to confuse an enemy pilot sufficiently that he would start to doubt his own bearings, the construction of Paris’ mirror image began in earnest at Villepinte to the northeast where a working model of the Gare de l’Est gradually began to take form.

The “fake Paris” was exquisite. No detail was overlooked: “complex, sprawling networks of lights arranged skillfully creating the impression of railway tracks and avenues, as well as storm lamps clustered together on ingenious moving platforms designed to simulate vast steam trains in motion. Immense empty sheds masquerading as factories had translucent sheets of painted canvas stretched tightly across their wooden frames which were illuminated from underneath, an arrangement that to anyone passing overhead would look remarkably like the dirty glass roofs characteristic of industrial buildings. Working furnaces were also installed to add an extra dimension of reality and the factory’s lights were even configured to dim noticeably during an air raid, fooling enemy pilots into believing that the facsimile buildings were, in fact, occupied.”

Because World War I ended, it was only this small part of Zone A that was built. The German bombing campaign came to an end in September 1918 and the armistice was signed at Compiègne two months later. The mock factories and railway network at Villepinte were dismantled shortly after the hostilities ceased. By the beginning of the 1920s little remained of the project. Though his fascinating idea never really got much further than the drawing board, the designs of Fernand Jacopozzi inspired similarly ambitious plans in the United States during World War II.

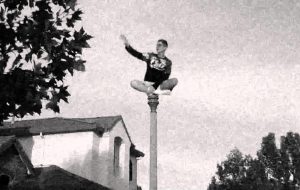

Alvin Kelly was born in Manhattan on May 11, 1893. His story began in a tragic way, because his father died before his birth and his mother died in childbirth with him. Kelly, now a newborn orphan, was raised in orphanages and passed around to various relatives. When Kelly turned 7, he started climbing onto poles and a few years later, he scaled the outside of buildings in his neighborhood…and by the way, his name wasn’t Alvin back then. It was Aloysius Anthony Kelly. He became Alvin when he ran away to go to work on a cargo ship. He was just 13 years old, and he changed his name to Alvin…probably to remain anonymous.

Alvin Kelly was born in Manhattan on May 11, 1893. His story began in a tragic way, because his father died before his birth and his mother died in childbirth with him. Kelly, now a newborn orphan, was raised in orphanages and passed around to various relatives. When Kelly turned 7, he started climbing onto poles and a few years later, he scaled the outside of buildings in his neighborhood…and by the way, his name wasn’t Alvin back then. It was Aloysius Anthony Kelly. He became Alvin when he ran away to go to work on a cargo ship. He was just 13 years old, and he changed his name to Alvin…probably to remain anonymous.

It wasn’t Kelly’s life as a runaway that made him unique, however, because runaways have existed for centuries. His childhood trick of climbing on poles stuck with him for the rest of his life. In fact, during the 1920s and 1930s, Kelly earned a name for himself…and a certain degree of notoriety…by sitting atop flag poles and other odd elevated perches for extended periods of time. I can’t imagine the purpose of such an act, and it’s not the most conventional way to fame, but for Alvin ‘Shipwreck’ Kelly it worked. Shipwreck Kelly, as he became known, is credited with starting the flagpole sitting fad, which, strangely, became popular in the Roaring Twenties, and he even earned a spot in the World Record Book for his sitting ability. I suppose an actor, comedian, magician, and such, needed a gimmick or a nickname, so Kelly began to use the nickname ‘Shipwreck’ claiming that he had survived the sinking of the Titanic. The story was proved to be untrue. Even then, Kelly claimed that he had many other close calls in his life. He said he had survived five shipwrecks, two plane crashes, three car accidents and one train derailment. In reality, Kelly most likely, acquired his nickname in the boxing ring. Not the greatest boxer, critics claimed he was often “adrift and ready to sink.”

As a teen and young man, Kelly hopped from job to job. His unusual ability to climb a pole and perch at the top did earn his work that he might not have otherwise been able to get. In addition to working at sea, he was a stunt pilot, movie double, steelworker, high diver, boxer, and a steeplejack. During World War I, Kelly was an ensign in the Naval Auxiliary Reserve, serving on the USS Edgar F. Luckenbach.

You might be wondering what started his Pole Sitting career. Well, like many a young man, Kelly was not one to back away from a dare. In 1924, he was dared by a friend to climb to the top of a flagpole in Philadelphia  outside a local department store. Of course, Kelly jumped at the chance to prove himself. He quickly ascended the pole and perched himself on top. The stunt attracted a large crowd, many of whom then went inside to shop in the department store. The store manager asked Kelly to stay up there a while…it was good for business! Newspapers carried pictures of Kelly’s stunt, many daredevils began copying his stunt. A fad was born! Soon pole sitting was a popular trick and copycat sitters did it for laughs, on a dare, or to protest. Even though so many others were doing it now, Kelly, the original pole sitter, continued his stunts to the delight of onlookers and journalists. Everyone knew he was the original, and the others were merely copycats.

outside a local department store. Of course, Kelly jumped at the chance to prove himself. He quickly ascended the pole and perched himself on top. The stunt attracted a large crowd, many of whom then went inside to shop in the department store. The store manager asked Kelly to stay up there a while…it was good for business! Newspapers carried pictures of Kelly’s stunt, many daredevils began copying his stunt. A fad was born! Soon pole sitting was a popular trick and copycat sitters did it for laughs, on a dare, or to protest. Even though so many others were doing it now, Kelly, the original pole sitter, continued his stunts to the delight of onlookers and journalists. Everyone knew he was the original, and the others were merely copycats.

Never content, Kelly continued to look for ways to outdo his latest tricks. In 1926 in Saint Louis, he stayed perched atop a pole for seven days and one hour. The next year, in June of 1927 in Newark, New Jersey, he extended his record to twelve days. Next, it was a 23 day sit on a flagpole in Carlin’s Park in Baltimore in 1929. His final record was set in 1930 when he stayed on a flagpole on Atlantic City’s Steel Pier for 49 days and one hour. I don’t know about you, but I can’t begin to imagine such extended days sitting on a flagpole. Nevertheless, for Kelly, it seemed to be a normal part of his daily routine. Newspapers of the 1920s loved to feature photographs of Kelly “sitting high in the air, especially ones of him doing everyday things, like shaving or reading a newspaper or brushing his teeth. During his sits, Kelly rarely ate, sustaining himself on coffee and cigarettes. Although he used a leg tether as a safeguard against falling, He learned to sleep sitting upright and he explained that he slept with his thumbs stuck in holes in the pole. If he started to lean one way or the other in his sleep, the pain in his thumbs would wake him in time for him to right himself.”

Kelly toured across the country during the peak of his fame, and charged admission for people to see him sitting on a flagpole. I would find watching someone sit on a pole would be boring, but people did. He once estimated that he spent 20,613 hours sitting on flag poles in his lifetime, including about 1,400 hours in  pouring down rain and 210 hours in sub-freezing temperatures. He was often hired to do publicity stunts because business owners knew he could draw a crowd. For example, on October 13, 1939, Kelly was hired to promote National Donut Dunking Week by sitting on a pole in Manhattan and eating 13 donuts dipped in coffee. I wonder how much they paid him for that stunt.

pouring down rain and 210 hours in sub-freezing temperatures. He was often hired to do publicity stunts because business owners knew he could draw a crowd. For example, on October 13, 1939, Kelly was hired to promote National Donut Dunking Week by sitting on a pole in Manhattan and eating 13 donuts dipped in coffee. I wonder how much they paid him for that stunt.

As the Great Depression of the 1930s progressed, people became less interested in Kelly’s tricks…and less tolerant. In 1935, he attempted to break his own record again, but the Bronx police said he was creating a public nuisance. The police threatened to chop down his pole, if he didn’t come down and when he did, he was promptly arrested. His last attempt at pole sitting was in Orange, Texas, in 1952. That day, while sitting on the pole, Kelly suffered two heart attacks and was forced to come down. He announced his retirement from pole sitting and died a week later.