sioux

Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. The Hunkpapa Lakota is a branch of the Sioux tribe. Sitting Bull was a rather charismatic person, and people were willing to follow him because of it. He was a rather mysterious historical figure. He was not impulsive, nor was he calm. Sitting Bull had a strange personality. He was most serious when he seemed to be joking. He also possessed the power of sarcasm, and he used it to his advantage. These things are likely what made him a good leader for his people.

Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. The Hunkpapa Lakota is a branch of the Sioux tribe. Sitting Bull was a rather charismatic person, and people were willing to follow him because of it. He was a rather mysterious historical figure. He was not impulsive, nor was he calm. Sitting Bull had a strange personality. He was most serious when he seemed to be joking. He also possessed the power of sarcasm, and he used it to his advantage. These things are likely what made him a good leader for his people.

Sitting Bull was a man given to having visions, and before the Battle of the Little Bighorn, he had a vision in which he saw many soldiers, “as thick as grasshoppers,” falling upside down into the Lakota camp. The Hunkpapa Lakota people took the vision as a sign of a major victory in which many soldiers would be killed…and maybe it was. Just three weeks later, on June 25, 1876, the confederated Lakota tribes, along with the Northern Cheyenne tribe, defeated the 7th Cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, decimating Custer’s battalion. The battle and it’s timing seemed to bear out Sitting Bull’s prophetic vision. Again, Sitting Bull’s leadership inspired his people to  a major victory.

a major victory.

Of course, the United States government immediately sent thousands more soldiers to the area, in response to the battle. Any Indians who were in small groups or alone were a target, as were villages of peaceful Indians. Many were forced to surrender over the next year, but Sitting Bull refused to. In May 1877, he led his band north to Wood Mountain, North-West Territories, which is now Saskatchewan. Canada. Sitting Bull stayed in that area until 1881, at which time he and most of his band returned to US territory and surrendered to US forces.

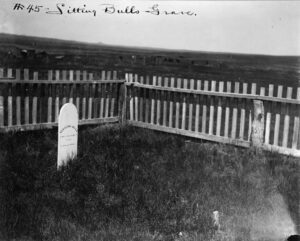

Sitting Bull’s charismatic personality helped him out again when he went to work as a performer with Buffalo  Bill’s Wild West show for a while, before returning to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota. That became one of the biggest mistakes Sitting Bull would ever make. Due to fears that he would use his influence to support the Ghost Dance movement, Indian Service agent James McLaughlin at Fort Yates ordered his arrest on December 15, 1890. Sitting Bull’s followers refused to go quietly, and in the struggle with police, Sitting Bull was shot in the side and head by Standing Rock policemen Lieutenant Bull Head and Red Tomahawk. His body was taken to nearby Fort Yates for burial. In 1953, his Lakota family exhumed what were believed to be his remains, reburying them near Mobridge, South Dakota, near his birthplace.

Bill’s Wild West show for a while, before returning to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota. That became one of the biggest mistakes Sitting Bull would ever make. Due to fears that he would use his influence to support the Ghost Dance movement, Indian Service agent James McLaughlin at Fort Yates ordered his arrest on December 15, 1890. Sitting Bull’s followers refused to go quietly, and in the struggle with police, Sitting Bull was shot in the side and head by Standing Rock policemen Lieutenant Bull Head and Red Tomahawk. His body was taken to nearby Fort Yates for burial. In 1953, his Lakota family exhumed what were believed to be his remains, reburying them near Mobridge, South Dakota, near his birthplace.

We hear many things about the different Indian Wars and battles. We also know that many of these wars were unnecessary, and were largely due to broken treaties that were made between the White Man and the Indians. Because the population of the United States was inevitable, I don’t know how we could have possibly left so much land exclusively for the use if the Indians, but there must have been better ways to work this out. Nevertheless, once a population explosion starts, it is impossible to stop it.

We hear many things about the different Indian Wars and battles. We also know that many of these wars were unnecessary, and were largely due to broken treaties that were made between the White Man and the Indians. Because the population of the United States was inevitable, I don’t know how we could have possibly left so much land exclusively for the use if the Indians, but there must have been better ways to work this out. Nevertheless, once a population explosion starts, it is impossible to stop it.

Of further concern to the government were the spiritual beliefs of the Indians. Throughout 1890, the United States government worried about the increasing influence at Pine Ridge of the Ghost Dance spiritual movement. The movement taught that the Indians had been defeated and confined to reservations because they had angered the gods by abandoning their traditional customs. This movement prompted many Sioux Indians to believed that if they practiced the Ghost Dance and rejected the ways of the white man, the gods would create the world anew and destroy all non-believers, including non-Indians.

The situation escalated when on December 15, 1890, reservation police tried to arrest Sitting Bull, the famous Sioux chief, because they mistakenly believed he was a Ghost Dancer. In the process of his arrest, they killed him, thereby increasing the tensions at Pine Ridge. Then, on December 29, the U.S. Army’s 7th Cavalry surrounded a band of Ghost Dancers under Big Foot, a Lakota Sioux chief, near Wounded Knee Creek. They demanded the Indians surrender their weapons. Immediately, a fight broke out between an Indian and a U.S.  soldier. A shot was fired, but it’s unclear who fired first. A brutal massacre followed, in which it’s estimated that between 150 and 300 Indians were killed, nearly half of them women and children. The cavalry lost 25 men. The conflict at Wounded Knee was originally referred to as a battle, but in reality it was a tragic and avoidable massacre. Surrounded by heavily armed troops, it’s unlikely that Big Foot’s band would have intentionally started a fight. Some historians speculate that the soldiers of the 7th Cavalry were deliberately taking revenge for the regiment’s defeat at Little Bighorn in 1876. Whatever the motives, the massacre ended the Ghost Dance movement and was the last major battle in America’s deadly war against the Plains Indians.

soldier. A shot was fired, but it’s unclear who fired first. A brutal massacre followed, in which it’s estimated that between 150 and 300 Indians were killed, nearly half of them women and children. The cavalry lost 25 men. The conflict at Wounded Knee was originally referred to as a battle, but in reality it was a tragic and avoidable massacre. Surrounded by heavily armed troops, it’s unlikely that Big Foot’s band would have intentionally started a fight. Some historians speculate that the soldiers of the 7th Cavalry were deliberately taking revenge for the regiment’s defeat at Little Bighorn in 1876. Whatever the motives, the massacre ended the Ghost Dance movement and was the last major battle in America’s deadly war against the Plains Indians.

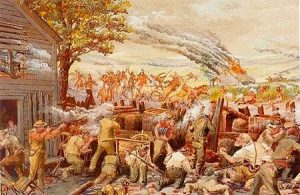

As the pioneers headed west, there were various disputes over ownership of the lands they were settling into. The Native American people did not think that they should have to surrender their lands to the White Man, but it seemed that they had no choice. Still, there were some Native Americans who refused to be pushed around by the government. On August 17, 1862, violence erupted in Minnesota as desperate Dakota Indians attacked white settlements along the Minnesota River. This was a fight that the Dakota Indians would eventually lose. They were no match for the US military, and six weeks later, it was over.

As the pioneers headed west, there were various disputes over ownership of the lands they were settling into. The Native American people did not think that they should have to surrender their lands to the White Man, but it seemed that they had no choice. Still, there were some Native Americans who refused to be pushed around by the government. On August 17, 1862, violence erupted in Minnesota as desperate Dakota Indians attacked white settlements along the Minnesota River. This was a fight that the Dakota Indians would eventually lose. They were no match for the US military, and six weeks later, it was over.

The Dakota Indians were often referred to as the Sioux, which I did not know was a derogatory name derived from part of a French word meaning “little snake.” It almost makes it seem like they were talking badly about them to their face, but so they couldn’t understand it. The government treated the Dakota poorly, and the Dakota saw their hunting lands dwindling  down, and apparently the provisions that the government promised to supply, rarely arrived. And now, to top it off, a wave of white settlers surrounded them too. To make matters worse, the summer of 1862 had been a harsh one, and cutworms had destroyed much of the crops. The Dakota were starving.

down, and apparently the provisions that the government promised to supply, rarely arrived. And now, to top it off, a wave of white settlers surrounded them too. To make matters worse, the summer of 1862 had been a harsh one, and cutworms had destroyed much of the crops. The Dakota were starving.

On August 17, the situation exploded when four young Dakota warriors returning from an unsuccessful hunt, stopped to steal some eggs from a white settlement. The were caught and they picked a fight with the hen’s owner. The encounter turned tragic when the Dakotas killed five members of the family. Now, the Dakota knew that they would be attacked. Dakota leaders, knew that war was at hand, so they seized the initiative. Led by Taoyateduta, also known as Little Crow, the Dakota attacked local agencies and the settlement of New  Ulm. Over 500 white settlers lost their lives along with about 150 Dakota warriors.

Ulm. Over 500 white settlers lost their lives along with about 150 Dakota warriors.

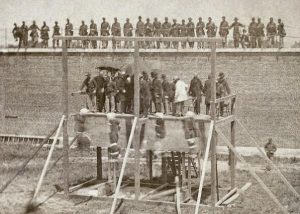

President Abraham Lincoln dispatched General John Pope, fresh from his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run, Virginia. Pope was to organize the Military Department of the Northwest. Some of the Dakota immediately fled Minnesota for North Dakota, but more than 2,000 were rounded up and over 300 warriors were sentenced to death. President Lincoln commuted most of their sentences, but on December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men were executed at Mankato, Minnesota. It was the largest mass execution in American history, and it was all because they were starving, and had no hope of living through that year.