ships

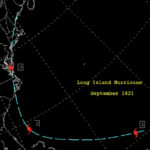

The normal hurricane season is from June 1 to November 30, and since we have our first hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico right now, it looks like it’s right on time. Nevertheless, for places like New York, where it is normally a little cooler, the hurricane season starts a little later, and may not really arrive at all. However, on June 4, 1825, a rare early hurricane arrived, moving off the East Coast and tracking south of New York. The hurricane caused several ship wrecks, and killed seven people.

The normal hurricane season is from June 1 to November 30, and since we have our first hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico right now, it looks like it’s right on time. Nevertheless, for places like New York, where it is normally a little cooler, the hurricane season starts a little later, and may not really arrive at all. However, on June 4, 1825, a rare early hurricane arrived, moving off the East Coast and tracking south of New York. The hurricane caused several ship wrecks, and killed seven people.

The National Hurricane Center, states that on average, hurricane winds have impacted the New York City area every 19 years, and major hurricanes, of a Category 3 or higher, only every 74 years. The highest hurricane reading, Category 5 hurricane is not expected to occur there at all, because of the climate conditions there.

Nevertheless, on June 4, 1825, forming ahead of what is now considered hurricane season, a severe tropical storm surprised the Atlantic seaboard from Florida to New York City. At that time, they did not have the prediction capabilities, and this storm was first sighted near Santo Domingo on May 28th. It moved across Cuba on June 1st, with gale force winds,  beginning at Saint Augustine, and approaching US soil on the June 2nd, and impacting Charleston, North Carolina on June 3rd.

beginning at Saint Augustine, and approaching US soil on the June 2nd, and impacting Charleston, North Carolina on June 3rd.

The tide in North Carolina rose six feet at New Bern and fourteen feet at Adams Creek. As the tide rushed in, more than 25 ships were driven ashore at Ocracoke, 27 near Washington, and also some at New Bern. The plantations on the coastal areas near the South River were inundated with water, causing a heavy loss of crops and livestock. New Bern experienced heavy damage near the waterfront.

The storm pummeled Norfolk, with horrific force for 27 hours as the storm passed by to the east beginning on the  morning of June 3rd. The wind was relentless, uprooting trees as it went. At noon on June 4th, stores on the wharves were flooded in a surge up five feet deep. High winds howled through the Washington DC area. The storm then moved northeast past Nantucket on June 5th.

morning of June 3rd. The wind was relentless, uprooting trees as it went. At noon on June 4th, stores on the wharves were flooded in a surge up five feet deep. High winds howled through the Washington DC area. The storm then moved northeast past Nantucket on June 5th.

The storm reminded many people of the September gale of 1821, except that the September gale would have been much more common. There haven’t been many early June hurricanes in that area since 1825, but there have been a number of hurricanes to hit the area since, including Hurricane Sandy, which did much damage in New York City, including the subway area.

If you were to travel to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, you would see what was once the fourth largest inland body of water in the world. The Aral Sea once had a water surface of 26,254 square miles. The salinity measured at 10g/L (grams of salt per liter of water). In comparison, the oceans are about 35 g/L, and the Dead Sea about 300 g/L. The Aral Sea has no outflow, and is fed by the Amu Darya and Syr Darya (Darya means river). It’s this lack of outflow that explains the high salinity. Still, it is much lass salty than the ocean, and especially much less than the Dead Sea.

If you were to travel to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, you would see what was once the fourth largest inland body of water in the world. The Aral Sea once had a water surface of 26,254 square miles. The salinity measured at 10g/L (grams of salt per liter of water). In comparison, the oceans are about 35 g/L, and the Dead Sea about 300 g/L. The Aral Sea has no outflow, and is fed by the Amu Darya and Syr Darya (Darya means river). It’s this lack of outflow that explains the high salinity. Still, it is much lass salty than the ocean, and especially much less than the Dead Sea.

The thing is…the Aral Sea was shrinking. By 1998, it had shrunk to just over 10,810 square miles. At that point, it became only the eighth largest lake in the world, and the salinity had increased to 45 g/L. By 2007, the lake had diminished to only 6,625 square miles, and became two separate basins…The North Aral Sea and the South Aral Sea. Now it is not even in the top ten list of the world’s largest lakes. The South Aral Sea is now further divided into two separate basins, east and west. Salinity in the southern basins is up to over 100 g/L, and has resulted in the death of most of the native flora and fauna of the lake. The lake used to have a fishing industry that supplied Russian markets with almost a quarter of their fish, while employing 40,000 people…but no more. Even the climate in the region has changed, with the loss of so much water, becoming more arid, with significantly decreased precipitation further adding to the decline of the Aral Sea. In total, the surface area has declined 90%, and the volume has decreased by 85%…basically like removing lakes the size of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined.

While these facts are strange in and of themselves, I wonder exactly how fast this transformation actually occurred. It is said that the sea level has dropped by over 98 feet in many places, leaving fishing boats stranded more than 60 miles from any shore. The ships were simply high and dry in the middle of the sea that had once been the source of income for their crews. The bottom of the lake became a new desert. The towns that had once been thriving were perched on vanished shorelines with toxic dust storms swirling around in the

wind. The people struggle in poverty and high rates of cancer, tuberculosis, digestive disorders, and anemia. The area today seems relatively safe to visit today, at least in the short term. What is interesting about the Aral Sea today is the it is still full of scores of ships…all high and dry on the sand. Why didn’t the owners take their ships away before the sea went dry? I guess maybe they believed the rains would come, and maybe they will, eventually. Unfortunately, it will simply be too late.

wind. The people struggle in poverty and high rates of cancer, tuberculosis, digestive disorders, and anemia. The area today seems relatively safe to visit today, at least in the short term. What is interesting about the Aral Sea today is the it is still full of scores of ships…all high and dry on the sand. Why didn’t the owners take their ships away before the sea went dry? I guess maybe they believed the rains would come, and maybe they will, eventually. Unfortunately, it will simply be too late.

It is a strange idea to give a pilot minimal training and then send them out to do a mission, but it depends, I suppose on the mission they are sent out to do. With Japan losing the war and most of the well trained pilots gone, as a result of major battle losses, a new breed of pilots was born. These new pilots were called Kamikaze or Suicide Bombers. They required only minimal training, because most would not return from their missions. It was part of a strange plan that required the pilot to deliberately give up their life for the mission. Of course, every soldier knows that the next mission could end badly, and that losing their life is never out of the question, but the idea of heading out with the specific plan of crashing your plane into a ship is very foreign to me.

It is a strange idea to give a pilot minimal training and then send them out to do a mission, but it depends, I suppose on the mission they are sent out to do. With Japan losing the war and most of the well trained pilots gone, as a result of major battle losses, a new breed of pilots was born. These new pilots were called Kamikaze or Suicide Bombers. They required only minimal training, because most would not return from their missions. It was part of a strange plan that required the pilot to deliberately give up their life for the mission. Of course, every soldier knows that the next mission could end badly, and that losing their life is never out of the question, but the idea of heading out with the specific plan of crashing your plane into a ship is very foreign to me.

From a training aspect, I suppose the Japanese felt it was a good tradeoff. The  Kamikaze pilots needed little training and could do great damage taking planes full of explosives and crash them into ships. Still, it seems to me that the cost of the training, and the loss of the planes on every mission…not to mention the loss of pilots, would completely defeat the purpose of the pilot training. Nevertheless, Kamikaze pilots have been around a while, and some nations see suicide missions as honorable somehow. Everyone knows that in a war, people are going to die, from both sides, but to specifically plan to take your own life for the mission, seems crazy to me, and to most sane people.

Kamikaze pilots needed little training and could do great damage taking planes full of explosives and crash them into ships. Still, it seems to me that the cost of the training, and the loss of the planes on every mission…not to mention the loss of pilots, would completely defeat the purpose of the pilot training. Nevertheless, Kamikaze pilots have been around a while, and some nations see suicide missions as honorable somehow. Everyone knows that in a war, people are going to die, from both sides, but to specifically plan to take your own life for the mission, seems crazy to me, and to most sane people.

For the Japanese, the Kamikaze mission brought a temporary measure of success, I suppose. At Okinawa, they sank 30 ships and killed almost 5,000 Americans. In that process, 30 pilots, who paid for the victory with their lives, were also lost in the mission. And in the end, the Kamikaze missions made no real difference in the war’s outcome. They still lost the war, and to me, that does not make the Kamikaze missions worthwhile. I don’t think it ever pays to take so little consideration for the lives of the people who serve under you. I believe that is the biggest mistake made by these horrific regimes. Such a murderous nation cannot long succeed, because people will eventually put a stop to it. The only sad part is that sometimes it takes so long to put a stop to these horrific acts. Kamikaze pilots, suicide bombers, and any other soldier who’s mission requires his own death, all fall into the category of a price too high to pay.

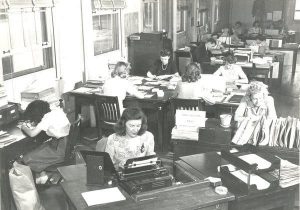

During World War II, when men were in short supply due to deployments, and the secret codes of the Japanese and Germans were causing major problems, the American government was faced with a difficult decision. They needed people who were qualified to break the codes of their enemies, and the only code breakers were in very short supply. The decision was made to search out college-educated women, preferably with degrees in Mathematics, Physics, and those who were fluent in other languages. There weren’t a lot of college educated women in those days, and even fewer with degrees in math or physics, but there were teachers. The Navy and the Army began recruiting these women. The women were required to go through a battery of tests and interviews to see if they had what it took to become code breakers. Many did not, but those who did were offered an exciting, but stressful career.

During World War II, when men were in short supply due to deployments, and the secret codes of the Japanese and Germans were causing major problems, the American government was faced with a difficult decision. They needed people who were qualified to break the codes of their enemies, and the only code breakers were in very short supply. The decision was made to search out college-educated women, preferably with degrees in Mathematics, Physics, and those who were fluent in other languages. There weren’t a lot of college educated women in those days, and even fewer with degrees in math or physics, but there were teachers. The Navy and the Army began recruiting these women. The women were required to go through a battery of tests and interviews to see if they had what it took to become code breakers. Many did not, but those who did were offered an exciting, but stressful career.

Upon arrival in Washington DC, these women found themselves in direct competition with the men, and the men didn’t like it one bit. Nevertheless, the feelings the men had for these women who were a threat to their  job, was at least matched by what the public thought of these women who, sworn to secrecy, had to lie about the work they did. They told people they were secretaries, and glorified waitresses, bring coffee to their bosses, while adding a bit of “interest” to the office. People thought these women were “loose” women…”gold diggers” looking for a husband, and because of the deep need for security, the women were forced to let people think what they wanted too.

job, was at least matched by what the public thought of these women who, sworn to secrecy, had to lie about the work they did. They told people they were secretaries, and glorified waitresses, bring coffee to their bosses, while adding a bit of “interest” to the office. People thought these women were “loose” women…”gold diggers” looking for a husband, and because of the deep need for security, the women were forced to let people think what they wanted too.

No matter what the public thought, these women code breakers were a vital part of the war effort. Our men were dying because we had no idea where the ships and submarines were until they struck. These women turned the tables in favor of the Allies, though few people ever knew it. The women were told they must never speak of what they did there…even after the war, and most of them took their secrets to the grave. While the women were forced to keep their secrets, they all knew that what they were doing mattered. They also knew things about the war, that others didn’t know. They knew the danger the Allied ships were in. They knew about ship that were torpedoed, almost as soon as it happened, and sometimes the ships were ones that friends and loved ones were stationed on…meaning they knew of their loved ones deaths almost immediately after they were killed.

At great sacrifice to themselves, the women code breakers fought a battle in the war that many people never  knew about. The stress, and just the shear gravity of the situation wore of the women. Some later had to seek psychiatric help, and some had nervous breakdowns, still they kept their secrets, lest their services were ever needed again. They kept them in case they ever had to be used again. They kept them because they had orders, and they would follow their orders no matter what. The work had been tedious, and sometimes codes took a long time to crack, but the determined women stuck it out, although most would never be thanked for their hard work. It didn’t matter. Their work was vital, and they were saving lives. That would have to be enough to carry them through the rest of their lives.

knew about. The stress, and just the shear gravity of the situation wore of the women. Some later had to seek psychiatric help, and some had nervous breakdowns, still they kept their secrets, lest their services were ever needed again. They kept them in case they ever had to be used again. They kept them because they had orders, and they would follow their orders no matter what. The work had been tedious, and sometimes codes took a long time to crack, but the determined women stuck it out, although most would never be thanked for their hard work. It didn’t matter. Their work was vital, and they were saving lives. That would have to be enough to carry them through the rest of their lives.

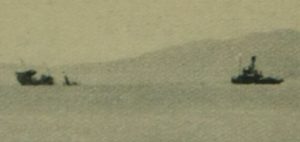

Over the years, ships that sailed the high seas, were faced with a number of perils, among them the biggest human danger there was…pirates. No area of the globe was particularly more dangerous than another, and no area was immune to attack, as was seen on October 19, 1927, when the Chinese steamer, SS Irene was on a voyage from Shanghai to Amoy with 258 passengers and crew. As she set out, she was taken over by pirates masquerading as passengers on that Wednesday. After boarding, the pirates quickly seized control of the ship and headed out to sea.

Over the years, ships that sailed the high seas, were faced with a number of perils, among them the biggest human danger there was…pirates. No area of the globe was particularly more dangerous than another, and no area was immune to attack, as was seen on October 19, 1927, when the Chinese steamer, SS Irene was on a voyage from Shanghai to Amoy with 258 passengers and crew. As she set out, she was taken over by pirates masquerading as passengers on that Wednesday. After boarding, the pirates quickly seized control of the ship and headed out to sea.

It was then that two L-class British submarines intercepted the vessel and demanded that they halt and surrender. The two submarines were based off Mendoza Island (now Shenggao Island) at the entrance of the bay. Upon their arrival, they had been ordered to split up. L4 went to patrol around the entrance of the bay and L5 was ordered to patrol within. It was at this point that they encountered the SS Irene. Pirates are a bull-headed group, and they aren’t afraid of very much. They are after all, outlaws, and that makes them a tough bunch. The pirates refused to surrender, and the submarines were ordered to fire. They fired two torpedoes into the ships hold. Even after being hit, the pirates continued to try to make it to shore, but they had been too badly damaged. Finally, they began to abandon ship. At this point, the ship stopped, but it was already beginning to sink. The British submarines then rescued the passengers and crew.

The Irene incident of 1927 was a significant event of the British anti-piracy operations in China during the first half of the 20th century. It was part of a British attempt to surprise the pirates of Bias Bay, about sixty miles from Hong Kong.  Royal Navy submarines were sent to stop the pirates, and the merchant ship SS Irene, of the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company, which had been taken over by the pirates on the night of October 19th was one if the first. The British were successful in thwarting the hijacking though they sank the ship. Sometimes, drastic measures must be taken in order to bring about the necessary changes. While we don’t hear about it as much, piracy still exists today. There may again come a time when drastic measures must be taken, and I know the authorities will do what has to be done.

Royal Navy submarines were sent to stop the pirates, and the merchant ship SS Irene, of the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company, which had been taken over by the pirates on the night of October 19th was one if the first. The British were successful in thwarting the hijacking though they sank the ship. Sometimes, drastic measures must be taken in order to bring about the necessary changes. While we don’t hear about it as much, piracy still exists today. There may again come a time when drastic measures must be taken, and I know the authorities will do what has to be done.

I have always been one to think that there is a logical explanation for everything that happens, but in the case of the Bermuda Triangle, it’s hard to stick to logical thinking, because it doesn’t follow logical lines. Over the past centuries, many ships and air planes have disappeared or met with fatal accidents in the triangular area on Atlantic ocean known as Bermuda Triangle. There are several cases in which no trace of the ships and aircraft were found even after extensive search operations were carried out for hundreds and thousands of square miles in the ocean.

I have always been one to think that there is a logical explanation for everything that happens, but in the case of the Bermuda Triangle, it’s hard to stick to logical thinking, because it doesn’t follow logical lines. Over the past centuries, many ships and air planes have disappeared or met with fatal accidents in the triangular area on Atlantic ocean known as Bermuda Triangle. There are several cases in which no trace of the ships and aircraft were found even after extensive search operations were carried out for hundreds and thousands of square miles in the ocean.

So…what happened to them. Of course, there have been many theories from a black hole to a time warp, but whatever it is, something happens to ships and planes in the Bermuda Triangle. Incidents of disappearances have been documented since the 1600s and continue today. There have been various explanations and theories behind these incidents, but in many cases the incidents are still unexplained.

In one shocking incident in 1945, a whole squadron of five training flights took off from Florida naval base under the leadership of an experienced captain. The planes never returned to the base. No one has come up with an explanation for the disappearance, and in fact, a Martin Mariner flying boat that was sent for the search operation, went missing too. None of these planes was ever heard from again.

In another incident in 1918, a large well known cargo ship went missing in the triangle area without a trace. All of the more than 300 crew members were lost. This was one of the largest lives lost case of disappearances in the Bermuda triangle. And there are many more such incidents. Theories such as methane gas blow out below the ocean causing ships to sink, electronic fog engulfing an aircraft and taking it to unknown zone, hurricanes destroying aircraft, and several other such theories try to explain such cases. They happen randomly, and not even once a year. That said, there is no way to anticipate them. For that reason, we are always shocked when  the latest incident happens. Tornado and severe weather warnings exist. We know when hurricanes are coming. We even know when snow or rain storms are coming. Unfortunately, these disappearances, like earthquakes are still very unpredictable. Nevertheless, from Christopher Columbus seeing strange lights and getting strange readings in 1492; to the disappearance of the Patriot, a ship which was carrying Theodosia Burr Alston, the daughter of former US Vice President Aaron Burr disappearing in 1812; to the latest event, the small private twin engine Mitsubishi MU-2B-40 fell victim to the Bermuda triangle on May 15, 2017 while flying from Puerto Rico. across a corner of the triangle to south Florida. The weather was fine, were no warnings…they simply vanished.

the latest incident happens. Tornado and severe weather warnings exist. We know when hurricanes are coming. We even know when snow or rain storms are coming. Unfortunately, these disappearances, like earthquakes are still very unpredictable. Nevertheless, from Christopher Columbus seeing strange lights and getting strange readings in 1492; to the disappearance of the Patriot, a ship which was carrying Theodosia Burr Alston, the daughter of former US Vice President Aaron Burr disappearing in 1812; to the latest event, the small private twin engine Mitsubishi MU-2B-40 fell victim to the Bermuda triangle on May 15, 2017 while flying from Puerto Rico. across a corner of the triangle to south Florida. The weather was fine, were no warnings…they simply vanished.

While islands don’t float and can’t flip over, they are subject to one hazard that can sometimes end with their disappearance…erosion. This isn’t a situation that many of us would ever notice in our lifetime, but on one island…Holland Island, located in the Chesapeake Bay, erosion quickly became a problem. In 1910, Holland Island, considered the most populated island in the Chesapeake Bay, was thriving with 360 residents. Besides historic Victorian homes, there were many other homes, shops, a school, and a church.

While islands don’t float and can’t flip over, they are subject to one hazard that can sometimes end with their disappearance…erosion. This isn’t a situation that many of us would ever notice in our lifetime, but on one island…Holland Island, located in the Chesapeake Bay, erosion quickly became a problem. In 1910, Holland Island, considered the most populated island in the Chesapeake Bay, was thriving with 360 residents. Besides historic Victorian homes, there were many other homes, shops, a school, and a church.

Despite its historic value, erosion gradually ate away at the island which greatly concerned its residents. Erosion just doesn’t care about historic value, sentimental value, or even about people’s lives. It is just a part of nature, and if a piece of ground doesn’t have a solid base, and plenty of vegetation to keep the ground in place, wind, rain, snow, and in this case, water from the bay will eventually erode the ground to a dangerous level. That was the situation that Holland Island found itself in 1910.

In 1914, in an attempt to try to slow the erosive loss of their precious island, the residents had stones shipped in to build walls and tried to even sink ships in an attempt to slow it down, but nothing worked. Finally, giving

up, most of the residents tore down their homes and moved inland. Many of the buildings still remained, but the town was largely a ghost town. When a tropical storm hit in 1918, it damaged the church. By 1922, the few people who had stayed finally left after the church closed down. One man, in 1995, tried for 15 years to preserve the island, spending a fortune, all to no avail. Finally, the last house crumbled and fell, ending the fight to save Holland Island.

up, most of the residents tore down their homes and moved inland. Many of the buildings still remained, but the town was largely a ghost town. When a tropical storm hit in 1918, it damaged the church. By 1922, the few people who had stayed finally left after the church closed down. One man, in 1995, tried for 15 years to preserve the island, spending a fortune, all to no avail. Finally, the last house crumbled and fell, ending the fight to save Holland Island.

The Dardanelles is a narrow strait running between the Black Sea in the east and the Mediterranean Sea in the west. In World War I it was a much contested area right from the start. It was the subject of a naval attack, spearheaded by Winston Churchill, who was at that time Britain’s young first lord of the Admiralty. On March 18, 1915, six English and four French battleships headed toward the strait. When they reached the area, Turkish mines blasted five of the ships, sinking three of them and forcing the Allied navy to draw back until land troops could be coordinated to begin an invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula. With troops from the Ottoman Empire and Germany mounting a spirited defense of the peninsula, however, the Gallipoli offensive turned into a significant setback for the Allies, with 205,000 casualties among British Empire troops and nearly 50,000 among the French.

The Dardanelles is a narrow strait running between the Black Sea in the east and the Mediterranean Sea in the west. In World War I it was a much contested area right from the start. It was the subject of a naval attack, spearheaded by Winston Churchill, who was at that time Britain’s young first lord of the Admiralty. On March 18, 1915, six English and four French battleships headed toward the strait. When they reached the area, Turkish mines blasted five of the ships, sinking three of them and forcing the Allied navy to draw back until land troops could be coordinated to begin an invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula. With troops from the Ottoman Empire and Germany mounting a spirited defense of the peninsula, however, the Gallipoli offensive turned into a significant setback for the Allies, with 205,000 casualties among British Empire troops and nearly 50,000 among the French.

When the Allies got involved, the latter offensives in Mesopotamia and Palestine saw more success. By September 1917, the crucial cities of Jerusalem and Baghdad were both in British hands. As the war stretched into the following year, these defeats and an Arab revolt had combined to destroy the Ottoman economy and devastate its land. Some 6 million people were dead and millions more starving. In early October 1918, unable to bank on a German victory any longer, the Turkish government in Constantinople decided to cut its losses and approached the Allies about brokering a peace deal. On October 30, 1918, British and Turkish representatives signed the Treaty of Mudros, which ended Ottoman participation in World War I. According to the terms of the treaty, Turkey had to demobilize its army, release all prisoners of war, and evacuate its Arab provinces, the majority of which were already under Allied control…and open the Dardanelles and Bosporus to Allied warships.

This last condition was fulfilled on November 12, 1918, the day after the armistice, when a squadron of British warships steamed through the Dardanelles, past the ruins of the ancient city of Troy, toward

Constantinople. By the post-war terms worked out by the Allies in the Treaty of Sevres in 1920, the waterways that were formerly under Ottoman rule…including the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmora and the Bosporus…were now placed under international control, with the designation that their “navigation…shall in future be open, both in peace and war, to every vessel of commerce or of war and to military and commercial aircraft, without distinction of flag.”

Constantinople. By the post-war terms worked out by the Allies in the Treaty of Sevres in 1920, the waterways that were formerly under Ottoman rule…including the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmora and the Bosporus…were now placed under international control, with the designation that their “navigation…shall in future be open, both in peace and war, to every vessel of commerce or of war and to military and commercial aircraft, without distinction of flag.”

Over the years of shipping and wars on the high seas, the ocean floor has become riddled with ships. They rest on the ocean floors almost like ghosts of the past, but all that is changing. The old wooden boats have most likely rotted away long ago but the metal ships, and those that carried or contained metal, have remained…some, like the World War I ships, for over a hundred years. Nevertheless, time and man have taken their toll on those ships too. Corrosion, sea life, and salvagers have been slowly dismantling these relics, to the point that some are completely gone. It is the natural course, I suppose, but it does seem sad to think that those great battle ships will soon be gone forever. I’m not the only one who feels sadness over that prospect either. As the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I rolled around on July 28, 2014, members of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) met in Belgium to discuss ways of protecting the valuable underwater cultural heritage of the historic war. The organization plans to extend a 2001 convention in order to safeguard thousands more historic sites, including many World War I shipwrecks that are threatened by salvage operations, looting and other brands of destruction. The 2001 convention originally applied only to sites sunk more than 100 years prior to 2001.

Over the years of shipping and wars on the high seas, the ocean floor has become riddled with ships. They rest on the ocean floors almost like ghosts of the past, but all that is changing. The old wooden boats have most likely rotted away long ago but the metal ships, and those that carried or contained metal, have remained…some, like the World War I ships, for over a hundred years. Nevertheless, time and man have taken their toll on those ships too. Corrosion, sea life, and salvagers have been slowly dismantling these relics, to the point that some are completely gone. It is the natural course, I suppose, but it does seem sad to think that those great battle ships will soon be gone forever. I’m not the only one who feels sadness over that prospect either. As the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I rolled around on July 28, 2014, members of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) met in Belgium to discuss ways of protecting the valuable underwater cultural heritage of the historic war. The organization plans to extend a 2001 convention in order to safeguard thousands more historic sites, including many World War I shipwrecks that are threatened by salvage operations, looting and other brands of destruction. The 2001 convention originally applied only to sites sunk more than 100 years prior to 2001.

I suppose that to many people, especially salvagers, these under sea relics mean just one thing…money. But to historians…even amateur historians, like me, it is unthinkable to know that those pieces of history have come to nothing more than a way for looters, or salvagers, as they like to call themselves, to make money. It is much like robbing a grave if you ask me. These places truly are an underwater heritage, and while I’m not against recreational divers going in for a look, they should be required to leave it all as they found it…no  souvenirs. As an avid hiker, I have learned to respect the natural areas I visit, by not stealing from the sites, and not littering either. That way, the next person who visits gets to see the same beautiful sights that I got to see. It should be the same on the ocean floor, and while I don’t see myself visiting any of those historic places, I would like to know that if diving expeditions go there and post videos, it would not be of the leftovers, following a salvage theft.

souvenirs. As an avid hiker, I have learned to respect the natural areas I visit, by not stealing from the sites, and not littering either. That way, the next person who visits gets to see the same beautiful sights that I got to see. It should be the same on the ocean floor, and while I don’t see myself visiting any of those historic places, I would like to know that if diving expeditions go there and post videos, it would not be of the leftovers, following a salvage theft.

With technology getting better and better, the locations of many, if not most of the undersea relics are well known, and unfortunately that also leaves them vulnerable to looting. I suppose it will still happen, even with increased regulation against it, but maybe some people would be deterred. That is the goal anyway. According to UNESCO’s Ulrike Guerin, protection under the convention “prevents the pillaging, which is happening on a very large scale, it prevents the commercial exploitation, the scrap metal recovery, and it will have regulations on the incidental impacts, such as the problem of trawlers going over World War I sites.” After so many years underwater, these ships are already fragile. It’s up to us, the people of the world to step up now, and protect them to the best of our ability. We may not be able to protect them from the ravages of the salt water, the sea life, and the years, but we can do our best to protect then from the salvagers, thieves, and looters of the world, who might go to the sight for the sole purpose of their own profit…at the expense of the people of the world.

The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage, introduced in 2001 was designed to help member nations better protect shipwrecks, submerged ruins and other valuable, increasingly fragile, parts  of their underwater heritage. The organization estimates that there are more than 3 million undiscovered shipwrecks scattered over the globe, including more than 12,500 sailing ships and war vessels lost at sea between 1824 and 1962 alone. With improved technology, these wrecks are becoming more accessible all the time, making them vulnerable to treasure hunters, commercial salvage operations and other types of looting…destroying these treasures for their own selfish, greedy gain. In my opinion, their preservation is more than just a good idea…it is our duty, and not only concerning World War I era wrecks, but also World War II era, and many other historic ship wrecks that could be photographed by legitimate expeditions for all to see.

of their underwater heritage. The organization estimates that there are more than 3 million undiscovered shipwrecks scattered over the globe, including more than 12,500 sailing ships and war vessels lost at sea between 1824 and 1962 alone. With improved technology, these wrecks are becoming more accessible all the time, making them vulnerable to treasure hunters, commercial salvage operations and other types of looting…destroying these treasures for their own selfish, greedy gain. In my opinion, their preservation is more than just a good idea…it is our duty, and not only concerning World War I era wrecks, but also World War II era, and many other historic ship wrecks that could be photographed by legitimate expeditions for all to see.

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In the summer of 1914, the Dresden was patrolling the Caribbean Sea. Its assignment was to safeguard German investments and German citizens living abroad in the region. Then, on July 20, during a bitter civil war in Mexico, the Dresden was called upon to give safe passage to Mexican president, Victoriano Huerta, by transporting him and his family as they escaped to Jamaica, where they received asylum from the British government. Then came news from Europe of Austria’s ultimatum to Serbia and the imminent possibility of war. The German’s put the fleet on alert. By the first week of August the nations of Europe were at war. The Dresden was sent to South America to attack British shipping interests there, and it sunk several merchant ships as it traveled to Cape Horn, at the southern tip of Chile. The Dresden eluded the British naval squadron in  the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

Just five weeks later, the Dresden was the only German ship to escape destruction at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on November 8, when the British light cruisers Inflexible and Invincible, commanded by Sir Doveton Sturdee, sank four of von Spee’s ships. Lost were Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Leipzig and Nurnberg. As a crew member of Dresden wrote later of watching one of the other ships sink, “Each one of us knew he would never see his comrades again, no one on board the cruiser can have had any illusions about his fate.” Then the Dresden escaped under cover of bad weather south of the Falkland Islands.

Dresden consistently avoided capture by the British navy over the next several months, while sinking a number of cargo ships and then seeking refuge in the network of channels and bays in southern Chile. In need of repairs, the Dresden put into an island off the Chilean coast, in Cumberland Bay on March 8th. Captain, Fritz Emil von Luedecke, had decided the repairs were necessary in the wake of such heavy and extended use. Captain von Luedecke sent out many messages asking for fuel in the hopes of reaching any passing coal ships in the area, but the messages were picked up the British ships, Kent and Glasgow six days later. After a  hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.

hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.