railroad

If you’ve ever been to the Smoky Mountains, then you know…you know just how beautiful they are. I’ve seen them, and they are beautiful. Nevertheless, there are things about the Smoky Mountains that I didn’t know. I love history and I love ghost towns, and now I find out that there is another one in the Smoky Mountains. It’s Daisy Town, Tennessee, and it has an interesting past. It was a century ago, when Daisy Town was thriving, that the Knoxville elites flocked to the Elkmont area. Sadly, today, the abandoned summer homes of Daisy Town make up a ghost town.

If you’ve ever been to the Smoky Mountains, then you know…you know just how beautiful they are. I’ve seen them, and they are beautiful. Nevertheless, there are things about the Smoky Mountains that I didn’t know. I love history and I love ghost towns, and now I find out that there is another one in the Smoky Mountains. It’s Daisy Town, Tennessee, and it has an interesting past. It was a century ago, when Daisy Town was thriving, that the Knoxville elites flocked to the Elkmont area. Sadly, today, the abandoned summer homes of Daisy Town make up a ghost town.

Elkmont started out in the 1830s, as a logging area, and so the moving into the area, and the area began to thrive. By the early 1900s, a lumber company built a railroad to transport the logs, and with that came people too, of course. When people saw that the area was going to make them rich, the affluent people who were living in Knoxville also began to visit the mountains finding them absolutely beautiful. They started building summer homes for themselves, and Daisy Town was born. By the 1920s, Elkmont was a summer playground for the city’s well-to-do population. Of course, if you wanted to spend your summers there, you would need money, so it was really an exclusive area.

The first thing built was the Appalachian Clubhouse, which was a social hub for the prominent members of  society, and with that and all the activities, came the cabins and cottages lining the one-lane road to the club. It was specifically this area that became known as Daisy Town. The club hosted dances, games, bingo, and horseshoes, through the 1920s and into the 1930s. Other areas, that had larger houses to draw the very wealthy, were nicknamed Millionaires Row and Society Hill. Nevertheless, time changes things, and even the fancy places like Daisy Town, Millionaires Row, and Society Hill have simply become the “Elkmont Ghost Town” and are nothing more than a tourist attraction for those of us who find ghost towns fascinating. It doesn’t detract from the beauty of the area, and for history buffs, like me, it probably adds to the attraction.

society, and with that and all the activities, came the cabins and cottages lining the one-lane road to the club. It was specifically this area that became known as Daisy Town. The club hosted dances, games, bingo, and horseshoes, through the 1920s and into the 1930s. Other areas, that had larger houses to draw the very wealthy, were nicknamed Millionaires Row and Society Hill. Nevertheless, time changes things, and even the fancy places like Daisy Town, Millionaires Row, and Society Hill have simply become the “Elkmont Ghost Town” and are nothing more than a tourist attraction for those of us who find ghost towns fascinating. It doesn’t detract from the beauty of the area, and for history buffs, like me, it probably adds to the attraction.

The whole decline of Daisy Town began in 1934, with the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. It didn’t happen overnight, of course, but the Elkmont area fell within the new park’s borders. The people who owned the homes weren’t forced out but were rather given a lifetime lease. Unfortunately for the families, the lease was not transferable, and as each owner died, the home was transferred to the park service. The slow end to Daisy Town and all the Elkmont vacation spots was complete by the early 1990s, leaving the park with 70 abandoned structures. Without proper care, the buildings began to decay, until all that was left was the eerie reminders of their heyday, such as is common to ghost towns.

All is not lost for Daisy Town, however. While the cabins and cottages are closed to the public, you can look inside and picture happier times. The Appalachian Clubhouse was given a different fate. The park service decided to restore it so that it could be used for events. Not only that, but nineteen other structures around Elkmont are slated for renovation by 2025, something I think is very cool. It’s sad to see these parts of our history being allowed to fall apart and disappear. For now, the walk along Jakes Creek Trail will provide view of this historic little area where you can still see chimneys, walls, and other remains of 1920s cabins. It’s an area I hope to visit one day.

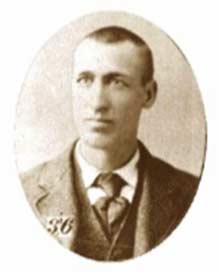

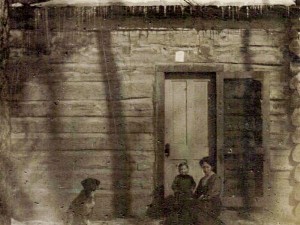

I don’t remember my grandmother, Anna Spencer, because she died when I was just over 2 months old. I have seen movies of her holding me, but my real memories of her ended there. Nevertheless, in my Uncle Bill Spencer’s family history, I learned most of what I know of my grandmother. She was a strong woman, who raised four children, mostly alone, because my grandfather, Allen Spencer was often away working on the railroad, or in the lumber industry. Grandma kept things together on the home front. She made life good for her children. They might not have had much money, but they were rich in love.

I don’t remember my grandmother, Anna Spencer, because she died when I was just over 2 months old. I have seen movies of her holding me, but my real memories of her ended there. Nevertheless, in my Uncle Bill Spencer’s family history, I learned most of what I know of my grandmother. She was a strong woman, who raised four children, mostly alone, because my grandfather, Allen Spencer was often away working on the railroad, or in the lumber industry. Grandma kept things together on the home front. She made life good for her children. They might not have had much money, but they were rich in love.

Grandma was a capable woman. She ran the farm, stacked hay, grew vegetables, canned vegetables, and so much more, but she was also a beautiful woman with soft expressive eyes, that told you she loved you. She loved her family so very much, and her children were her whole world. She worked so hard to make a home for her children, and she was so proud of them…her two beautiful daughters and her two handsome sons. She raised capable kids who grew into responsible adults and made their mother proud. All of them grew to have families, and gave her and grandpa 13 grandchildren, and the numbers of people stemming from grandma and grandpa’s union is still growing.

Grandma struggled with rheumatoid arthritis in her later years, and was often confined to a wheelchair, but her sweet spirit, and loving nature never changed. Her children did their best to care for her until the day that she went to Heaven, and their love for her never ceased. I wish I had been able to know this incredible woman,

because I know in my heart that I would have loved her very much. I think that I and many of her children, grandchildren, great grandchildren, and beyond, carry that same tenacity and stubborn drive to succeed against all odds. Some things are passed down through the genes, while others are passed down through teaching…and some are a combination of the two. Grandma used both to help her family become the wonderful people they are. Today is the 136th anniversary of Grandma’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandma. We love and miss you very much.

because I know in my heart that I would have loved her very much. I think that I and many of her children, grandchildren, great grandchildren, and beyond, carry that same tenacity and stubborn drive to succeed against all odds. Some things are passed down through the genes, while others are passed down through teaching…and some are a combination of the two. Grandma used both to help her family become the wonderful people they are. Today is the 136th anniversary of Grandma’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandma. We love and miss you very much.

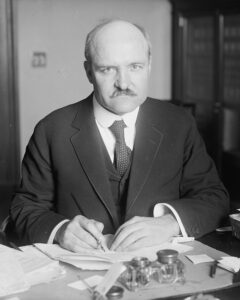

No matter what your opinion is on the use of Daylight Savings Time and Standard Time, the was originally a good reason for it, and that reason still applies today in many ways. The Standard Time Act of 1918, which was also known as the Calder Act (after the senator who sponsored the bill…William M. Calder), was the first United States federal law implementing Standard time and Daylight Saving Time in the United States. Prior to the Calder Act, the railroads had instituted time zones so that the rail schedule could have much needed consistency. Before time zones, no one had any idea when the train was due. It was a big mess. The Time Zone system defined five time zones for the United States and authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to define the limits of each time zone.

No matter what your opinion is on the use of Daylight Savings Time and Standard Time, the was originally a good reason for it, and that reason still applies today in many ways. The Standard Time Act of 1918, which was also known as the Calder Act (after the senator who sponsored the bill…William M. Calder), was the first United States federal law implementing Standard time and Daylight Saving Time in the United States. Prior to the Calder Act, the railroads had instituted time zones so that the rail schedule could have much needed consistency. Before time zones, no one had any idea when the train was due. It was a big mess. The Time Zone system defined five time zones for the United States and authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to define the limits of each time zone.

When the need for Daylight Savings Time came up, the original point of it was to save fuel by setting working hours so they coincided with the hours of natural daylight. While many people may not like that much, I think that a sensible person  can at least see the purpose of it. The act included a section that talked about the repeal of the change in one year, but in the end, it was decided that it was necessary to continue the practice. In fact, they could see no usefulness in repealing it, because the fuel savings had not changed. So, the practice has continued to this day. The Calder Act came about in answer to the European countries, who were already using the practice successfully.

can at least see the purpose of it. The act included a section that talked about the repeal of the change in one year, but in the end, it was decided that it was necessary to continue the practice. In fact, they could see no usefulness in repealing it, because the fuel savings had not changed. So, the practice has continued to this day. The Calder Act came about in answer to the European countries, who were already using the practice successfully.

Those who dislike the practice have been trying to repeal the act for as long as I can remember anyway, and with no success. I suppose that someday, they may succeed, but I’m not sure they will find that life without the time changes will be as amazing as they think. The sun will continue to make its  seasonal adjustments, and without the time changes, we will at some point, find ourselves wishing for another hour of daylight. The first time change to Daylight Saving Time took place on March 19, 1918, and it has been in practice since that time. I, personally, look forward to Daylight Saving Time every year. The longer days and more light make me feel happy, and I find that the few days or a week of adjustment is of little consequence in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, I’m sure I’ll hear lots of differing opinions from my readers. This year, Daylight Saving Time started on March 12, and Standard Time will begin on November 5…just so you know.

seasonal adjustments, and without the time changes, we will at some point, find ourselves wishing for another hour of daylight. The first time change to Daylight Saving Time took place on March 19, 1918, and it has been in practice since that time. I, personally, look forward to Daylight Saving Time every year. The longer days and more light make me feel happy, and I find that the few days or a week of adjustment is of little consequence in the grand scheme of things. Nevertheless, I’m sure I’ll hear lots of differing opinions from my readers. This year, Daylight Saving Time started on March 12, and Standard Time will begin on November 5…just so you know.

The “almost” ghost town of Bushong, Kansas got its start in 1886 when the Missouri Pacific Railroad built its tracks across Northern Lyon County. The railroad station was named Weeks, as was the town at first, after Joseph Weeks, who donated 20 acres of land to the railroad. After the railroad built on part of the acreage, it sold some of the acreage as town lots. Although there was no town company, per se, Joseph Weeks also platted another 20 acres and sold lots on that, and a town was born. The Missouri Pacific Railroad also built a large tank pond one mile east of town to supply the steam engines with water, as they pulled their trains over the hills to Council Grove. There were large pastures filled with cattle in the area, and cattle pens were constructed to hold the cattle for shipping. The railroad also bought a valuable stone quarry south of Bushong and shipped quarried rock to Kansas City, about an hour and a half to their Northeast.

The “almost” ghost town of Bushong, Kansas got its start in 1886 when the Missouri Pacific Railroad built its tracks across Northern Lyon County. The railroad station was named Weeks, as was the town at first, after Joseph Weeks, who donated 20 acres of land to the railroad. After the railroad built on part of the acreage, it sold some of the acreage as town lots. Although there was no town company, per se, Joseph Weeks also platted another 20 acres and sold lots on that, and a town was born. The Missouri Pacific Railroad also built a large tank pond one mile east of town to supply the steam engines with water, as they pulled their trains over the hills to Council Grove. There were large pastures filled with cattle in the area, and cattle pens were constructed to hold the cattle for shipping. The railroad also bought a valuable stone quarry south of Bushong and shipped quarried rock to Kansas City, about an hour and a half to their Northeast.

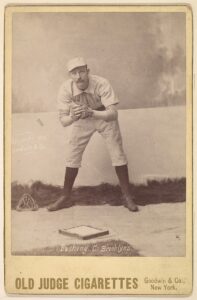

As the town grew, more buildings were needed. The first school building was erected in 1886. The school was a two-story wood-frame structure, and it housed grades 1-8. The school was used until 1948. Then, students were moved to the brick high school building, and the old school building was sold and removed. When the new settlement gained a post office on January 31, 1887, the name was changed to Bushong in honor of Al “Doc” Bushong, who was a baseball player for the Saint Louis Browns. The player’s greatest success came when he was the starting catcher in the 1886 World Series. The Saint Louis Browns of the American Association beat the Chicago White Stockings of the National League. The team owner wanted to do something special for his team to mark their success. Somehow, he made the arrangements for each player to have a town named after them. While all the players had towns named after them, Bushong is the only town that still carries the name of the player they were to have honored. In 1887, Bushong had a population of about 75 people. The first station agent was R D Cottrell, who also built the Bushong Hotel, which he operated with his wife until his death, then she remarried and continued to operate the hotel for a few more years. Other early businesses included a general store, a flour mill, blacksmith, lumber yard, boarding house, and a hog fence factory.

In the town’s saddest event, twelve members of the population died within 48 hours of each other in February 1894, when a diphtheria epidemic gripped the town. It was the last great pandemic of the 19th century, and among the deadliest pandemics in history. The worst effects of the pandemic took place from October  1889 to December 1890, with recurrences in March to June 1891, November 1891 to June 1892, winter of 1893–1894, and early 1895. At the same time, the school in Bushong was closed. The towns first and only doctor, Chester L Stocks, set up his practice in 1896. He was also a druggist, and he continued to serve the community until 1934.

1889 to December 1890, with recurrences in March to June 1891, November 1891 to June 1892, winter of 1893–1894, and early 1895. At the same time, the school in Bushong was closed. The towns first and only doctor, Chester L Stocks, set up his practice in 1896. He was also a druggist, and he continued to serve the community until 1934.

For a brief time in 1899, the town boasted a newspaper called the Bushong Bulletin. It was a small town, and really, how much news could there be. A Methodist church was established that year. It had one large room with a pot-bellied stove in the center and an organ. By 1910, Bushong was a thriving town with a population of 250. The post office even had one rural route. The town also had a number of general stores, a hotel, public school, telegraph, telephone, and express service, and its railroad was providing a considerable amount of shipping. For many years trains stopped at Bushong for passengers. When passenger service was discontinued, trains could still be stopped by “flagging” them down to load freight or livestock. It finally became necessary to establish the Bushong Rural High School, and classes were held in the upper room of the grade school in 1913. Later, students were taught in other town buildings, with the first graduation taking place in 1916. The town also became home to The Bushong State Bank, which was chartered in 1916, but like many other banks, it failed during the Great Depression and closed in 1932. A new brick High School was erected in 1918 consisting of four rooms. Later additions were made, including a gymnasium in 1926. Unfortunately, a fire in the 1920s destroyed a large portion of the downtown area, and the buildings were never rebuilt. In 1923 a new Methodist church building was erected on the same site as the first one. The building utilized the bell from the old church in the belfry. That year, the town’s population was 150. However, the next year, severe drought and heat caused many settlers to move from the area. Bushong was incorporated in 1927, and L A Grimsley was elected as the first mayor. At that time, the town had a population of about 150 and continued to maintain its two room grade school and a four-room rural high school. The Methodist Church and Sunday School were well attended. At about that same time, electricity was approved, and in 1936 Bushong voted to sell their utility to Kansas Electric Company of Emporia. Bushong’s early telephone system was part of the Farmers Mutual Telephone Association, a cooperative company that everyone helped to construct and care for lines and poles. The telephone company was sold in 1960. Like numerous other communities, Bushong was hit hard by the Great Depression and never recovered.

In 1955, school enrollment had dropped to such a degree that Bushong consolidated with the other area schools. High school pupils went to nearby Allen until Northern Heights opened in the fall of 1957, consolidating the high schools of Bushong, Allen, Admire, and Miller. Grade school continued at Bushong until 1966 when all area 3rd and 4th graders went to Bushong and the other grades to Allen and Admire. The school finally closed  in 1970, and the city purchased the building for use as a Civic Center. Currently, the building is abandoned. The railroad discontinued the depot in 1957, and later the depot building was torn down.

in 1970, and the city purchased the building for use as a Civic Center. Currently, the building is abandoned. The railroad discontinued the depot in 1957, and later the depot building was torn down.

During the Cold War, Bushong was again in the spotlight. I became the location of one of the first generations of nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles. One of several Atlas class missile silos developed in the Midwest, active from 1961-1965, was part of the 548th Strategic Missile Squadron was located in the small town. Unfortunately, that was still not enough to save the town from virtual extinction. Bushong’s post office closed on July 2, 1976. Today, Bushong is called home to only about 30 people with no open businesses. The old community is located about 20 miles northwest of Emporia. It’s strange how things work out. What starts out as a thriving town, sometimes gives way to a ghost town, while other times, the town grows to greatness.

While most of the economy in Southeast Texas depended on agriculture, cattle ranching, and the lumber business in the 19th century, things were about to change. The presence of oil was known, but untapped until 1901 when the oil industry would change the landscape of the region. Uses for oil date back many years. In the 1500s, the Spanish used oil from seeps near Sabine Pass for caulking their ships, and to the north, settlers near Nacogdoches used seeping oil for lubricants before 1800. There were numerous discoveries in east and central Texas in the later 1800s, especially at Corsicana in 1896. Attempts were made to drill wells at Spindletop 1893 and 1896 and at Sour Lake in 1896, but they had no successful oil production along the Gulf Coast until the Lucas Gusher came in on Spindletop Hill on January 10, 1901.

While most of the economy in Southeast Texas depended on agriculture, cattle ranching, and the lumber business in the 19th century, things were about to change. The presence of oil was known, but untapped until 1901 when the oil industry would change the landscape of the region. Uses for oil date back many years. In the 1500s, the Spanish used oil from seeps near Sabine Pass for caulking their ships, and to the north, settlers near Nacogdoches used seeping oil for lubricants before 1800. There were numerous discoveries in east and central Texas in the later 1800s, especially at Corsicana in 1896. Attempts were made to drill wells at Spindletop 1893 and 1896 and at Sour Lake in 1896, but they had no successful oil production along the Gulf Coast until the Lucas Gusher came in on Spindletop Hill on January 10, 1901.

Spindletop Hill was a salt dome oil field, that was located in the southern portion of Beaumont, Texas. People had long suspected that oil might be under the hill as the area had been known for its sulfur springs and  bubbling gas seepages that would ignite if lit. Then in August, 1892, several men including George W. O’Brien, George W. Carroll, and Pattillo Higgins formed the Gladys City Oil, Gas, and Manufacturing Company to do exploratory drilling on Spindletop Hill.

bubbling gas seepages that would ignite if lit. Then in August, 1892, several men including George W. O’Brien, George W. Carroll, and Pattillo Higgins formed the Gladys City Oil, Gas, and Manufacturing Company to do exploratory drilling on Spindletop Hill.

By September 1901, there were at least six successful wells on Gladys City Company lands. Wild speculation drove land prices around Spindletop to incredible heights. One man who had been trying to sell his tract there for $150 for three years sold his land for $20,000; the buyer promptly sold to another investor within fifteen minutes for $50,000. One well, representing an initial investment of under $10,000, was sold for $1,250,000. Legal entanglements and multimillion-dollar deals became almost commonplace. An estimated $235 million had been invested in oil that year in Texas; while some had made fortunes, others lost everything.

Following the success of the oil industry at Spindletop Hill, many people, including my grandparents, Allen and  Anna Spencer would make their way to Texas in search of a better life. They would settle on the oilfields near Ranger, Texas. They didn’t find any oil fields, so their income came from his work for other people in the oilfields. These days people working in the oilfield business make good money, but as near as I can tell oilfield workers averaged about 90 cents an hour in 1919, which would be about $11.74 an hour today. That’s pretty poor wages, especially for the oilfield, but I suppose people didn’t realize how valuable they really were. Needless to say, the oilfield was not the place my grandfather would choose to make his living, and eventually they returned to Wisconsin where he went to work for the railroad.

Anna Spencer would make their way to Texas in search of a better life. They would settle on the oilfields near Ranger, Texas. They didn’t find any oil fields, so their income came from his work for other people in the oilfields. These days people working in the oilfield business make good money, but as near as I can tell oilfield workers averaged about 90 cents an hour in 1919, which would be about $11.74 an hour today. That’s pretty poor wages, especially for the oilfield, but I suppose people didn’t realize how valuable they really were. Needless to say, the oilfield was not the place my grandfather would choose to make his living, and eventually they returned to Wisconsin where he went to work for the railroad.

When a body of water stands between two places that people need to go, there are a few options to solve the dilemma…a bridge, a road around, or as was the case of a way across the Detroit River, a tunnel. With a river, you can’t really go around, so often it’s a bridge, but in this case there was a great deal of opposition to a bridge over the river. Since the beginning of the 19th century, Detroiters and Windsorians had been trying to find a way to move people and goods back and forth across the Detroit River. For decades, railroad interests proposed tunnels and bridges galore, but powerful advocates of marine shipping always managed to block those projects, because they did not want to lose business to faster and more capacious trains. Plans for bridges were particularly troubling to those shippers, since just one low-hanging bridge had the potential to keep high-masted sailing vessels off the river altogether.

When a body of water stands between two places that people need to go, there are a few options to solve the dilemma…a bridge, a road around, or as was the case of a way across the Detroit River, a tunnel. With a river, you can’t really go around, so often it’s a bridge, but in this case there was a great deal of opposition to a bridge over the river. Since the beginning of the 19th century, Detroiters and Windsorians had been trying to find a way to move people and goods back and forth across the Detroit River. For decades, railroad interests proposed tunnels and bridges galore, but powerful advocates of marine shipping always managed to block those projects, because they did not want to lose business to faster and more capacious trains. Plans for bridges were particularly troubling to those shippers, since just one low-hanging bridge had the potential to keep high-masted sailing vessels off the river altogether.

In 1871, the region’s railroads finally won permission to build a trans-national tunnel, and workers began to dig into the river at the foot of Detroit’s San Antoine Street. They were forced to abandon the project just 135 feet  under the river, however, when they struck a pocket of sulfurous gas that made workers so ill that none could be persuaded to return. Likewise, in 1879, another tunnel had to be abandoned when it ran right into some unexpectedly difficult to excavate limestone under the river. The first successful Michigan to Canada tunnel project finally opened in 1891. It was the 6,000 foot long Grand Trunk Railway Tunnel at Port Huron.

under the river, however, when they struck a pocket of sulfurous gas that made workers so ill that none could be persuaded to return. Likewise, in 1879, another tunnel had to be abandoned when it ran right into some unexpectedly difficult to excavate limestone under the river. The first successful Michigan to Canada tunnel project finally opened in 1891. It was the 6,000 foot long Grand Trunk Railway Tunnel at Port Huron.

Soon enough, it was clear to most people on both sides of the border that they needed to build some sort of structure for transporting automobiles across the river too. In June 1919, the mayors of Detroit and Windsor decided to build a city to city tunnel that would serve as a memorial to the American and Canadian soldiers who had died in World War I. Even after advocates of the under-construction Ambassador Bridge tried to frighten away the tunnel’s backers by spreading rumors about the danger of subterranean carbon monoxide poisoning, the tunnel boosters were undeterred. One said, they were “inspired by God to have this tunnel built.” Construction began in 1928. First, barges were used to dredge a 2,454 foot long trench across the river. Then workers sank nine 8,000 ton steel and concrete tubes into the trench and welded them together. Finally, an  elaborate ventilation system was built to make sure that the air in the tunnel safe to breathe.

elaborate ventilation system was built to make sure that the air in the tunnel safe to breathe.

On Nov 1, 1930, President Herbert Hoover turned a telegraphic Golden Key in the White House to mark the opening of the 5,160 foot long Detroit-Windsor Tunnel between the United States city of Detroit, Michigan, and the Canadian city of Windsor, Ontario. The tunnel opened to regular traffic on November 3, 1930. The first passenger car it carried was a 1929 Studebaker. In the first nine weeks it was open, nearly 200,000 cars passed through the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel. Today, about 9 million vehicles use the tunnel each year.

Jonathan Luther “John” “Casey” Jones was born on March 14, 1863. As a boy, he lived near Cayce, Kentucky, which is where his nickname of “Cayce” came from, but he chose to spell it “Casey”. Jones went to work for the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and performed well and was promoted to brakeman on the Columbus, Kentucky to Jackson, Tennessee route, and then to fireman on the Jackson, Tennessee to Mobile, Alabama route. That caught my attention, because my grandfathers and other family members worked for the railroad too, but it was not working on the railroad that made Casey famous…at least not totally anyway. Casey always dreamed of being an engineer. He worked hard, but did receive nine citations for rule violations, and 145 total days suspended. In the year prior to his death, Jones had not been cited for any rules infractions. His dreams came true, but not in the way he expected. In the summer 1887, a yellow fever epidemic struck many train crews on the neighboring Illinois Central Railroad, providing an unexpected opportunity for faster promotion of firemen on that line. On March 1, 1888, Jones switched to the Illinois Central Railroad, taking a freight locomotive between Jackson, Tennessee and Water Valley, Mississippi.

Jonathan Luther “John” “Casey” Jones was born on March 14, 1863. As a boy, he lived near Cayce, Kentucky, which is where his nickname of “Cayce” came from, but he chose to spell it “Casey”. Jones went to work for the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and performed well and was promoted to brakeman on the Columbus, Kentucky to Jackson, Tennessee route, and then to fireman on the Jackson, Tennessee to Mobile, Alabama route. That caught my attention, because my grandfathers and other family members worked for the railroad too, but it was not working on the railroad that made Casey famous…at least not totally anyway. Casey always dreamed of being an engineer. He worked hard, but did receive nine citations for rule violations, and 145 total days suspended. In the year prior to his death, Jones had not been cited for any rules infractions. His dreams came true, but not in the way he expected. In the summer 1887, a yellow fever epidemic struck many train crews on the neighboring Illinois Central Railroad, providing an unexpected opportunity for faster promotion of firemen on that line. On March 1, 1888, Jones switched to the Illinois Central Railroad, taking a freight locomotive between Jackson, Tennessee and Water Valley, Mississippi.

Jones was a bit of a risk taker, but I doubt if some of the people who knew about some of his “risks” would hold that against him. A little-known example of Jones’ heroic act saved the life of a little girl. As Jones’ train approached Michigan City, Mississippi, he had walked out on the running board to oil the relief valves. He had finished well before they arrived at the station, as planned, and was returning to the cab when he noticed a group of small children dart in front of the train some 60 yards ahead. They all cleared the rails easily except for a little girl who suddenly froze in fear at the sight of the oncoming iron horse. Jones shouted to Stevenson to reverse the train and yelled to the girl to get off the tracks in almost the same breath. Then he realize that she was frozen in fear. He raced to the tip of the cowcatcher and braced himself on it, reaching out as far as he could to pull the frightened but unharmed girl from the rails.

On April 30, 1900, while Casey was running the Cannonball Express, and trying to make up for a late start, it would be his heroics that would cost him his life. As Casey was coming into Vaughan, Mississippi, he did not know that three separate trains were in the station at Vaughan…double-header freight train No. 83 and long freight train No. 72 were both in the passing track to the east of the main line. As the combined length of the trains was ten cars longer than the length of the east passing track, some of the cars were stopped on the main line. The two sections of northbound local passenger train No. 26 had arrived from Canton earlier, and required a “saw by” for them to get to the “house track” west of the main line. The “saw by” maneuver required that No. 83 back up (onto the main line) to allow No. 72 to move northward and pull its overlapping cars off the main line and onto the east side track from the south switch, thus allowing the two sections of No. 26 to gain access to the west house track. The “saw by”, however, left the rear cars of No. 83 overlapping above the north switch and on the main line…right in Jones’ path. As workers prepared a second “saw by” to let Jones pass, an air hose broke on No. 72, locking its brakes and leaving the last four cars of No. 83 on the main line.

Jones was almost back on schedule, running at about 75 miles per hour toward Vaughan, and traveling through a 1.5 mile left-hand curve that blocked his view. Webb’s view from the left side of the train was better, and he was first to see the red lights of the caboose on the main line. “Oh my Lord, there’s something on the main line!” he yelled to Jones. Jones quickly yelled back “Jump Sim, jump!” to Webb, who crouched down and jumped from the train, about 300 feet before impact, and knocked unconscious by his fall. The last thing Webb heard as he jumped was the long, piercing scream of the whistle as Jones warned anyone still in the freight train looming ahead. He was only two minutes behind schedule. Jones reversed the throttle and slammed the airbrakes into  emergency stop, but “Ole 382” quickly plowed through a wooden caboose, a car load of hay, another of corn, and halfway through a car of timber before leaving the track. He had reduced his speed from about 75 miles per hour to about 35 miles per hour when he hit. Because Jones stayed on board to slow the train, he saved the passengers from serious injury and death. He was the only fatality of the collision. His watch stopped at the time of impact…3:52 am on April 30, 1900. Legend holds that when his body was pulled from the wreckage, his hands still clutched the whistle cord and brake. A stretcher was brought from the baggage car on No. 1, and crewmen of the other trains carried his body to the depot, a half-mile away.

emergency stop, but “Ole 382” quickly plowed through a wooden caboose, a car load of hay, another of corn, and halfway through a car of timber before leaving the track. He had reduced his speed from about 75 miles per hour to about 35 miles per hour when he hit. Because Jones stayed on board to slow the train, he saved the passengers from serious injury and death. He was the only fatality of the collision. His watch stopped at the time of impact…3:52 am on April 30, 1900. Legend holds that when his body was pulled from the wreckage, his hands still clutched the whistle cord and brake. A stretcher was brought from the baggage car on No. 1, and crewmen of the other trains carried his body to the depot, a half-mile away.

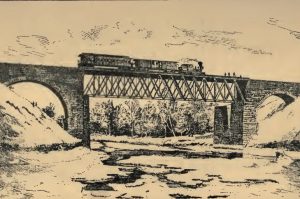

Through the centuries, new designs were developed to build things we needed. As the railroad moved across the nation, track laying came across deep gorges and flat plains. Of course, the flat plains were easy to deal with, and trains could simply go around any hills in the area, but the rivers and gullies were a bigger problem. They needed bridges, and so Charles Collins and Amasa Stone jointly designed a bridge to be used at Ashtabula, Ohio. It was the first Howe-type wrought iron truss bridge built. Collins was worried about the bridge, thinking that it was “too experimental” and needed further evaluation. Nevertheless, higher powers prevailed, and the bridge was built. Collins had been right to be concerned. The bridge lasted just 11 years before it collapsed.

Through the centuries, new designs were developed to build things we needed. As the railroad moved across the nation, track laying came across deep gorges and flat plains. Of course, the flat plains were easy to deal with, and trains could simply go around any hills in the area, but the rivers and gullies were a bigger problem. They needed bridges, and so Charles Collins and Amasa Stone jointly designed a bridge to be used at Ashtabula, Ohio. It was the first Howe-type wrought iron truss bridge built. Collins was worried about the bridge, thinking that it was “too experimental” and needed further evaluation. Nevertheless, higher powers prevailed, and the bridge was built. Collins had been right to be concerned. The bridge lasted just 11 years before it collapsed.

On December 28, 1876, a Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway train…the Pacific Express left New York. It struggled along through the drifts and the blinding storm. The train was pulling into Ashtabula, Ohio, shortly before 8:00pm on December 29, 1876, several hours behind schedule. The eleven cars were a heavy burden to the two engines. The leading locomotive broke through the drifts beyond the ravine, and rolled on across the bridge at Ashtabula at less than ten miles an hour. The head lamp could barely be seen because the air was thick with the driving snow. The leading engine reached solid ground, and the engineer had just given it steam…when something in the undergearing of the bridge snapped.

What followed was a horror beyond horrors…not only for the victims, but for the rescuers as well…maybe even more so for the rescuers. As the bridge crumbled beneath the weight of the train, the train and its 159 passengers fell 70 feet into the river below. More than 90 people, passengers and crew, were killed when the train hit the river and ignited into a huge ball of flames. Only the lead engine escaped the fall. As the bridge fell, the engineer gave it a quick head of steam, which tore the draw head from its tender, and the liberated engine shot forward and buried itself in the snow. The engineer escaped with a broken leg. The proportions of the Ashtabula horror are still only approximately known. Daylight, brought with it the opportunity to find and count the saved. It also revealed the fact that two out of every three passengers on the train were lost. Of the 160 passengers who the injured conductor reports as having been on board, fifty nine were found or accounted for as surviving. The remaining 100, burned to ashes or shapeless lumps of charred flesh, were lying under the ruins of the bridge and train. Every possible element of horror was there. First came the crash of the bridge, the agonizing moments of suspense as the seven laden cars plunged down their fearful leap to the icy riverbed. Then the fire, that devoured all that had been left alive by the crash. The water that gurgled up from under the broken ice brought with it another form of death. And finally, the biting blast of freezing air filled with snow, that froze those who had escaped the water and fire.

For the rescuers, the horror had just begun. I can’t think of anything worse than seeing those bodies after they were horribly mangled, drowned, and burned…some beyond recognition, some completely cremated. The number of persons killed cannot be accurately stated, because it is not known exactly how many there were on the train. It is supposed that some of the bodies were entirely consumed in the flames, as well. The official list of those killed and those who have died of their injuries, gives the number as fifty five, but it is suspected to be somewhat higher. There is no death list to report…and in fact, there can be none. There are no remains that can ever be identified. The three charred, shapeless lumps recovered were burned beyond recognition. For the rest, there are piles of white ashes in which were found the crumbling particles of bones. In other places masses of black, charred debris, half under water, which may contain fragments of bodies, but nothing that resembled a human body. It is thought that there may have been a few corpses under the ice, as there were women and children who jumped into the water and sank, but none have been recovered. Periodically, as people began looking for people that were missing around the country, and they were able to place them, as possibly on the train, more supposed victims have been identified…at least there is the possibility that they were a victim.

The Ashtabula, Ohio Railroad Disaster, often referred to simply as the Ashtabula Disaster or the Ashtabula Horror, was one of the worst railroad disasters in American history. The event occurred just 100 yards from the railroad station at Ashtabula, Ohio. It’s topped only by the Great Train Wreck of 1918 in Nashville, Tennessee. Charles Collin, the chief engineer, who knew as few men did the defects of that bridge, but was powerless to repair them, had been listening for this very crash for years. Collins, locked himself in his bedroom and shot himself while the inquest was in progress rather than tell the world all he believed he knew. Collins was found  dead in his bedroom of a gunshot wound to the head. He had tendered his resignation to the Board of Directors the previous Monday. Collins was believed to have committed suicide out of grief and feeling partially responsible for the tragic accident, however, a police report at the time suggested the wound had not been self inflicted. Documents discovered in 2001 and an examination of Collins’ skull suggest that he had indeed been murdered. Amasa Stone committed suicide seven years later after experiencing financial difficulties with some foundries he had interests in, suffering from severe ulcers that kept him from sleeping, and scorn from the public over the disaster.

dead in his bedroom of a gunshot wound to the head. He had tendered his resignation to the Board of Directors the previous Monday. Collins was believed to have committed suicide out of grief and feeling partially responsible for the tragic accident, however, a police report at the time suggested the wound had not been self inflicted. Documents discovered in 2001 and an examination of Collins’ skull suggest that he had indeed been murdered. Amasa Stone committed suicide seven years later after experiencing financial difficulties with some foundries he had interests in, suffering from severe ulcers that kept him from sleeping, and scorn from the public over the disaster.

Over the years, man has tried many ways to harness water. Water is a necessity to life, and without it, all things would die off. Some projects worked out better than others, and some simply needed to be replaced sooner than they were in order to prevent disaster. A good example of that is the earthen dam. An earthen dam is a dam that is built out of rocks and dirt, instead of steel and concrete. Of course, when dams were first built, earthen dams were the only way to go, but after so many failed, a new type of dam had to be designed, in order to save lives. One such failure was the earthen dam built in 1840 on the Little Conemaugh River, fourteen miles upstream from Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Johnstown is sixty miles east of Pittsburgh, in a valley near the Allegheny, Little Conemaugh, and Stony Creek Rivers. The area lies in a floodplain that has had frequent disasters. This time would prove to be one of them. At nine hundred by seventy two feet, this dam was the largest earthen dam in the United States, creating the largest man-made lake at that time…Lake Conemaugh. At a time when here were no railroads in the area for transporting goods, the dam and its extensive canal system was the only way to transport goods to the people, but it became obsolete as the railroads replaced the canal as a means of transporting goods. The canal system was left to become a victim of the elements, and with its neglect, also came the neglect of the dam. In reality, people just didn’t really think anything would happen, and they most likely looked at the dam as just a part of the landscape.

Over the years, man has tried many ways to harness water. Water is a necessity to life, and without it, all things would die off. Some projects worked out better than others, and some simply needed to be replaced sooner than they were in order to prevent disaster. A good example of that is the earthen dam. An earthen dam is a dam that is built out of rocks and dirt, instead of steel and concrete. Of course, when dams were first built, earthen dams were the only way to go, but after so many failed, a new type of dam had to be designed, in order to save lives. One such failure was the earthen dam built in 1840 on the Little Conemaugh River, fourteen miles upstream from Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Johnstown is sixty miles east of Pittsburgh, in a valley near the Allegheny, Little Conemaugh, and Stony Creek Rivers. The area lies in a floodplain that has had frequent disasters. This time would prove to be one of them. At nine hundred by seventy two feet, this dam was the largest earthen dam in the United States, creating the largest man-made lake at that time…Lake Conemaugh. At a time when here were no railroads in the area for transporting goods, the dam and its extensive canal system was the only way to transport goods to the people, but it became obsolete as the railroads replaced the canal as a means of transporting goods. The canal system was left to become a victim of the elements, and with its neglect, also came the neglect of the dam. In reality, people just didn’t really think anything would happen, and they most likely looked at the dam as just a part of the landscape.

By 1889, Johnstown had grown to a population of 30,000 people, many of whom worked in the steel industry…ironically. On May 30, 1889, it began to rain, and continued steadily all day. No one really gave any thought the potential harm so much rain could bring to the nearly sixty year old earthen dam. The dam had a spillway, and so everything seemed safe, but the spillway became clogged with debris, that could not be dislodged. On May 31, 1889, an engineer at the dam saw the warning signs, but the only way to notify anyone was to ride his horse into the village of South Fork to warn the people…a ride that took an eternity in the face of the impending disaster. Nevertheless, it should have been enough time, but the telegraph lines were down, and no warning ever reached Johnstown. At 3:10pm, the dam collapsed with a roar that could be heard for miles. The water, moving at 40 miles per hour barreled down on the towns in it’s path, wiping out everything that got in its way. At Johnstown, 2,200 people lost their lives that day, including one Thomas Knox and his wife. Thomas, like a large number of the flood victims was never found. While I’m not sure that Thomas Knox is related to my husband, Bob Schulenberg’s family, it is quite likely that he is, as there are a number of Thomas Knox’s in the family…though none that I have found so far that died in the Johnstown Flood.

The people in the path of the raging flood waters, were tossed around, along with all that debris, including thirty three train engines that were pulled into the flood waters. I’m sure that for many, death did not come  from drowning, but rather from blunt force trauma. Nevertheless, some people did manage to climb atop the debris, only to be burned alive when much of the debris caught fire, when it was caught in a bridge downstreem and burst into flames. There was a report of a baby that survived on the floor of a house that floated 75 miles downstream, but that was something that was not confirmed. It was during the Johnstown flood, that the American Red Cross handled its first major relief effort. Clara Barton arrived five days after the flood to lead the relief. In the end, it took five years to rebuild Johnstown, which went through disastrous floods in 1936 and 1977. I have to wonder if they should just move the town, but with no major floods since 1977, it’s hard to say.

from drowning, but rather from blunt force trauma. Nevertheless, some people did manage to climb atop the debris, only to be burned alive when much of the debris caught fire, when it was caught in a bridge downstreem and burst into flames. There was a report of a baby that survived on the floor of a house that floated 75 miles downstream, but that was something that was not confirmed. It was during the Johnstown flood, that the American Red Cross handled its first major relief effort. Clara Barton arrived five days after the flood to lead the relief. In the end, it took five years to rebuild Johnstown, which went through disastrous floods in 1936 and 1977. I have to wonder if they should just move the town, but with no major floods since 1977, it’s hard to say.

For a time, my grandfather, Allen Luther Spencer, worked in the lumber business. It started when he and my grandmother’s brother, Albert Schumacher, decided to go trapping in northern Minnesota. That venture didn’t go very well, and they just about froze to death. It was at that time that they decided to go into the lumber business. Being a lumberjack is no easy job, and was probably much more dangerous in my grandfather’s day, than it is now. Back then, lumberjacks, as they were called did everything from chopping down the trees, to cutting them with a saw, climbing up in the tree to get to the top. You name it, if it pertained to logging, they did it. They called it harvesting, and it begins with the lumberjack. The term lumberjack is not a term that is used much

For a time, my grandfather, Allen Luther Spencer, worked in the lumber business. It started when he and my grandmother’s brother, Albert Schumacher, decided to go trapping in northern Minnesota. That venture didn’t go very well, and they just about froze to death. It was at that time that they decided to go into the lumber business. Being a lumberjack is no easy job, and was probably much more dangerous in my grandfather’s day, than it is now. Back then, lumberjacks, as they were called did everything from chopping down the trees, to cutting them with a saw, climbing up in the tree to get to the top. You name it, if it pertained to logging, they did it. They called it harvesting, and it begins with the lumberjack. The term lumberjack is not a term that is used much  these days, because the modern way of harvesting is very different. Lumberjacks were pretty much a pre-1945 term. Hand tools were the harvest tools used, because there were no machines like what we have now.

these days, because the modern way of harvesting is very different. Lumberjacks were pretty much a pre-1945 term. Hand tools were the harvest tools used, because there were no machines like what we have now.

The actual work of a lumberjack was difficult, dangerous, intermittent, low-paying, and primitive in living conditions, but the men built a traditional culture that celebrated strength, masculinity, confrontation with danger, and resistance to modernization. These days, there are a few people who actually celebrate the lumberjacking trade. Mostly it involves competitions, but just by watching, you can see that being a lumberjack was not a job for a weakling.

Lumberjacks, and their families, usually lived in a lumber camp, moving from site to site and the job moved. I  know that my grandmother and my Aunt Laura spent time in the lumber camps. From what I’ve been told, the houses were little more that a log tent. They didn’t stay very warm, because there were gaps in the walls, and my guess is that they could only use a certain amount of wood a day, so it didn’t eat into the profits. I suppose that the owner of the logging operation made a good profit, but that doesn’t mean that the people who worked for them made a great deal of money, because they really didn’t. Being a lumberjack was really a far from glamorous occupation, and like most really physical jobs, not one that a man can do for too many years. Before long, my grandfather, like most lumberjacks, moved on to other jobs, in grandpa’s case the railroad.

know that my grandmother and my Aunt Laura spent time in the lumber camps. From what I’ve been told, the houses were little more that a log tent. They didn’t stay very warm, because there were gaps in the walls, and my guess is that they could only use a certain amount of wood a day, so it didn’t eat into the profits. I suppose that the owner of the logging operation made a good profit, but that doesn’t mean that the people who worked for them made a great deal of money, because they really didn’t. Being a lumberjack was really a far from glamorous occupation, and like most really physical jobs, not one that a man can do for too many years. Before long, my grandfather, like most lumberjacks, moved on to other jobs, in grandpa’s case the railroad.