native americans

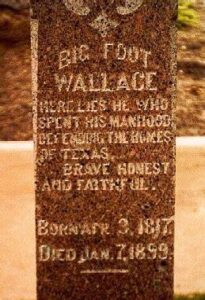

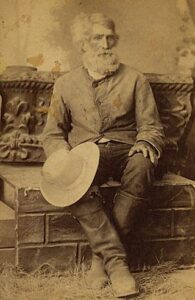

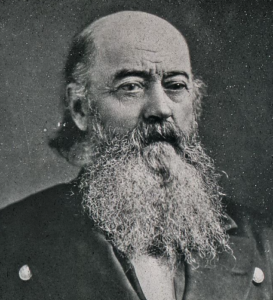

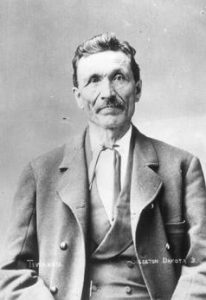

William Alexander Anderson Wallace was born in Lexington, Virginia on April 3, 1817, parents of Scots-Irish descent. He might have stayed in Virginia, but in 1836, when he was just 19 years old, Wallace received news that one of his brothers had been killed in the Battle of Goliad, which was an early confrontation in the Texan war of independence with Mexico. Wallace promised to “take pay of the Mexicans” for his brother’s death. So, with revenge on his mind, Wallace left Lexington and headed for Texas. Upon his arrival, Wallace found that the war was already over. With no further need of his anger-revenge agenda, Wallace found he liked the spirited independence of the new Republic of Texas and decided to stay.

William Alexander Anderson Wallace was born in Lexington, Virginia on April 3, 1817, parents of Scots-Irish descent. He might have stayed in Virginia, but in 1836, when he was just 19 years old, Wallace received news that one of his brothers had been killed in the Battle of Goliad, which was an early confrontation in the Texan war of independence with Mexico. Wallace promised to “take pay of the Mexicans” for his brother’s death. So, with revenge on his mind, Wallace left Lexington and headed for Texas. Upon his arrival, Wallace found that the war was already over. With no further need of his anger-revenge agenda, Wallace found he liked the spirited independence of the new Republic of Texas and decided to stay.

Wallace was a big man, standing over six feet tall and weighing around 240 pounds. His size alone made him an intimidating figure, but his nickname of “Big Foot” came from his unusually large feet. Wallace didn’t think he would ever get the chance to fight Mexicans, but in 1842, he finally got his chance when he joined with other Texans to stop an invasion by the Mexican General Adrian Woll. During another skirmish with Mexicans, Wallace was captured, and he spent the next two years serving hard time in the notoriously brutal Perote Prison in Vera Cruz. He was finally released in 1844.

After his time as a prisoner of war, Wallace returned to Texas and found himself feeling tired of the rigidness of the formal Texan military force. So, he decided to leave the military for the less rigid organization of the Texas Rangers. The Texas Ranger program was part law-enforcement officers and part soldiers. They fought both bandits and Native Americans in the large, but sparsely populated reaches of the Texan frontier. “Big Foot” Williams served under the famous Ranger John Coffee Hays until the start of the Civil War in 1861. Williams was against the idea of Texas secession from the Union, but he was unwilling to fight against his own people. He had really assimilated himself into Texas…it was a big part of him. Williams spent most of the Civil War defending Texas against Native American attacks along the frontier. He didn’t get involved in the “politics” of the matter, he just knew that he was now a Texan, and he had to defend her at all costs.

Wallace spent many years in the wilds of Texas, having hundreds of adventures. He was attacked by Native Americans while working as a stage driver on the dangerous San Antonio-El Paso route. In that event, he

barely escaped with his life. The Natives stole his mules and left him stranded in the Texas desert. Forced to walk all the way to El Paso, he later said that he ate 27 eggs at the first house he came to after his long walk. Then, he went into town to have a “real meal.”

barely escaped with his life. The Natives stole his mules and left him stranded in the Texas desert. Forced to walk all the way to El Paso, he later said that he ate 27 eggs at the first house he came to after his long walk. Then, he went into town to have a “real meal.”

After many years and many adventures and in his old age, Wallace decided he had enough of life as a fighter and adventurer. He was tired and ready to learn how to relax. The state of Texas, in exchange for his years of service, granted Wallace land along the Medina River and in Frio County in the southern part of the state. Wallace loved to tell anyone who would listen, with highly embellished tales of his frontier days. Soon he became a well-known folk hero to the people of Texas. Wallace died on January 7, 1899. He is buried in the Texas State Cemetery.

Being in the fur trade, especially back in the 1800s was no picnic. While the trapper was the one with the traps and the guns, that doesn’t mean that the wild animals couldn’t get the better of them from time to time. In addition, the hardships endured by even the most resilient of trappers, such as being alone in the wilderness and in constant danger of conflict with both wild animals and men, are beyond our ability to comprehend. Most perished in the quiet of remote areas, their names now lost, the valor of their final struggles unrecorded. Only the archives of the major fur companies offer scant references to such events deemed significant enough to document.

Being in the fur trade, especially back in the 1800s was no picnic. While the trapper was the one with the traps and the guns, that doesn’t mean that the wild animals couldn’t get the better of them from time to time. In addition, the hardships endured by even the most resilient of trappers, such as being alone in the wilderness and in constant danger of conflict with both wild animals and men, are beyond our ability to comprehend. Most perished in the quiet of remote areas, their names now lost, the valor of their final struggles unrecorded. Only the archives of the major fur companies offer scant references to such events deemed significant enough to document.

These events typically took place in the great mountains, where trappers held rendezvous and spent the majority of their lives. The catastrophic Battle of Pierre’s Hole, the valiant exploration of Utah, and the initial advance into California are all laden with dramatic episodes. However, these incidents occurred too far to the west to be included in the scope of this current work.

In the initial years of exploration, with beaver trapping along the streams, the Great Plains served primarily as a thoroughfare from civilized regions to the more lucrative mountainous areas beyond. Travelers, whether alone or in groups, journeyed up the Missouri River by boat or trekked along the Platte River valley on foot, aiming for the distant mountain ranges. Undoubtedly, they experienced considerable hardship, adventure, and conflicts with Native Americans along those extensive prairie stretches, yet these events were deemed too mundane to merit inclusion in the fur companies’ matter-of-fact records.

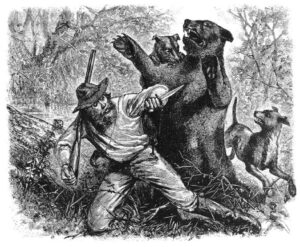

One man had a harrowing experience, and somehow it was deemed important to make it into the annals of history. The remarkable survival of Hugh Glass is a testament to the resilience and fortitude of these frontiersmen. Glass was part of Andrew Henry’s group on an expedition to the Yellowstone River. While hunting near the Grand River, a grizzly bear charged from the brush, knocked him down, ripped a chunk of flesh from him, and fed it to her cubs. Glass attempted to flee, but the bear quickly attacked again, biting his shoulder and causing severe injuries to his hands and arms. At that moment, his fellow hunters arrived and killed the bear. Glass was grievously injured and barely alive. He was not expected to live. In the hostile territory of the Native Americans, the group had to move on swiftly. Eventually, Major Henry persuaded two men to stay with Glass by offering a reward, while the rest continued on. The two were John S Fitzgerald and a man named “Bridges,” who some say was a young James “Jim” Bridger, the same Jim Bridger who would become a renowned trapper. That has not been confirmed. They stayed with Glass for five days, but losing hope in his recovery and seeing no signs of imminent death, they departed, taking his rifle and gear. Upon rejoining their group, they reported Glass as deceased.

Yet, Glass was still alive. Regaining consciousness, he dragged himself to a nearby spring. There, he found wild cherries and buffalo berries, which sustained him as he gradually regained his strength. Eventually, he embarked on a solitary trek to his destination, Fort Kiowa, on the Missouri River, 100 miles distant. He began his journey with barely enough strength to move, without provisions or any means to obtain them, in a land where any wandering Indian could easily overpower him. However, his will to live and a burgeoning desire for vengeance against those who had abandoned him spurred him on. Luck appeared to be on his side. He stumbled upon wolves attacking a buffalo calf. After the wolves had killed it, he scared them off and took the meat, consuming it as best as he could without a knife or fire. Carrying as much as possible, he continued determinedly and, despite immense suffering and difficulties, ultimately arrived at Fort Kiowa, located in what is now South Dakota.

Glass returned to the field before his wounds had fully healed. Heading east with a group of trappers along the Missouri River, they approached the Mandan villages, and he chose to traverse a bend in the river on foot. That turned out to be a wise move when Arikara Indians attacked the boats, killing everyone aboard. Glass, who was too weak to fight, narrowly escaped and was rescued by friendly Mandan Indians who took him to Tilton’s Fort. Driven by a desire for revenge against the two who had abandoned him in the mountains, he left Tilton’s that very night. So, Glass set out, braving the wilderness alone. He traveled for 38 days through territory hostile with Indian tribes, until he arrived at Fort Henry near the confluence of the Big Horn River in what is now Montana. There, he learned that the men he was after had headed east. Undeterred, he seized an opportunity to deliver a dispatch to Fort Atkinson, Nebraska.

Then, after completely healing from his injuries, Glass resumed his quest to locate Fitzgerald and “Bridges.” He made his way to Fort Henry on the Yellowstone River, only to discover it abandoned. A left-behind note revealed that Andrew Henry and his group had moved to a new encampment at the Bighorn River’s mouth. Upon reaching this location, Glass encountered “Bridges” and seemingly pardoned him due to his young age, before rejoining Ashley’s company.

Glass eventually discovered that Fitzgerald had enlisted in the army and was posted at Fort Atkinson, now in Nebraska. Glass chose to spare Fitzgerald’s life, knowing that the army captain would execute him for murdering a fellow soldier. Nevertheless, the captain demanded Fitzgerald return the rifle he had taken from Glass. Upon returning it, Glass cautioned Fitzgerald to never desert the army, or he would face death at Glass’s hands. A later account by Glass’s companion, George C Yount, which wasn’t published until 1923, revealed that Glass received $300 in restitution. I’m sure Fitzgerald felt he got off easy and had no plans to leave the army.

In early 1833, Glass, along with fellow trappers Edward Rose and Hilain Menard, was killed on the Yellowstone River during an Arikara attack. A monument honoring Glass stands near the location of his mauling on the southern bank of what is now Shadehill Reservoir in Perkins County, South Dakota, at the confluence of the Grand River. The adjacent Hugh Glass Lakeside Use Area also offers a state-maintained campground and picnic site at no cost.

In early 1833, Glass, along with fellow trappers Edward Rose and Hilain Menard, was killed on the Yellowstone River during an Arikara attack. A monument honoring Glass stands near the location of his mauling on the southern bank of what is now Shadehill Reservoir in Perkins County, South Dakota, at the confluence of the Grand River. The adjacent Hugh Glass Lakeside Use Area also offers a state-maintained campground and picnic site at no cost.

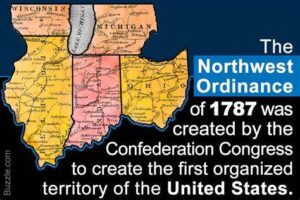

It never really occurred to me that the formation of new states in the United States would be the huge undertaking that it actually became. I just assumed that as the settlers moved into an area, they eventually got populated enough to decide to be a state. Of course, I realized that they would have to “petition” the national government for acceptance, but that wasn’t all there was to it at all. The United States had acquired the Northwest Territory (the Midwest today) in a number of steps. First, when it was relinquished by the British. Second, extinguishment of states’ claims west of the Appalachians. And finally, usurpation or purchase of lands from the Native Americans. Originally, the Hudson’s Bay Company acquired the area under a charter from Charles II in 1670. Then, in 1869, the Canadian government bought the land from the company. The boundaries we now have were set in 1912. In 1870, Canada acquired an area known as Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company for £300,000 (Canadian $1.5 million) and a large land grant.

It never really occurred to me that the formation of new states in the United States would be the huge undertaking that it actually became. I just assumed that as the settlers moved into an area, they eventually got populated enough to decide to be a state. Of course, I realized that they would have to “petition” the national government for acceptance, but that wasn’t all there was to it at all. The United States had acquired the Northwest Territory (the Midwest today) in a number of steps. First, when it was relinquished by the British. Second, extinguishment of states’ claims west of the Appalachians. And finally, usurpation or purchase of lands from the Native Americans. Originally, the Hudson’s Bay Company acquired the area under a charter from Charles II in 1670. Then, in 1869, the Canadian government bought the land from the company. The boundaries we now have were set in 1912. In 1870, Canada acquired an area known as Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company for £300,000 (Canadian $1.5 million) and a large land grant.

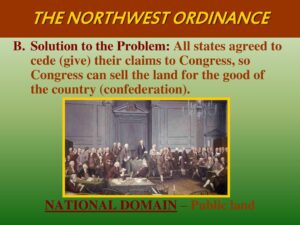

That left the United States with a kind of dilemma, since they wanted to make sure these new states were run in the way they had originally designed. So, on July 13, 1787, Congress enacts the Northwest Ordinance, to structure the settlement of the Northwest Territory. Since the formation of new states was a new venture for  the young nation, they had to create a policy for the addition of these new states. Vitally important was the need to make sure their new nation thrived and survived. The members of Congress knew that if their new confederation were to survive intact, it had to resolve issue of the states’ competing claims to western territory.

the young nation, they had to create a policy for the addition of these new states. Vitally important was the need to make sure their new nation thrived and survived. The members of Congress knew that if their new confederation were to survive intact, it had to resolve issue of the states’ competing claims to western territory.

That said, in 1781, the state of Virginia began the process by ceding its extensive land claims to Congress. That bold move made other states more comfortable in doing the same. Thomas Jefferson first proposed a method of incorporating these western territories into the United States in 1784. His plan was to basically turn the territories into colonies of the existing states. Since each state was to have their own constitution, the ten new northwestern territories would select the constitution of an existing state that closely aligned with their own values. Once that process was complete, the new territory (colony) had to wait until its population reached 20,000 to join the confederation as a full member. That process made Congress nervous, because they feared that the new states…10 in the Northwest as well as Kentucky, Tennessee and Vermont…would quickly gain enough power to outvote the old ones, so Congress never passed Thomas Jefferson’s proposal.

It would be three more years before the Northwest Ordinance which proposed that “three to five new states be created from the Northwest Territory. Instead of adopting the legal constructs of an existing state, each territory would have an appointed governor and council. When the population reached 5,000, the residents could elect their own assembly, although the governor would retain absolute veto power. When 60,000 settlers  resided in a territory, they could draft a constitution and petition for full statehood. The ordinance provided for civil liberties and public education within the new territories, but did not allow slavery.”

resided in a territory, they could draft a constitution and petition for full statehood. The ordinance provided for civil liberties and public education within the new territories, but did not allow slavery.”

The last part angered the pro-slavery Southerners, but they were willing to go along with this because they hoped that the new states would be populated by white settlers from the South. They believed that although these Southerners would have no enslaved workers of their own, they would not join the growing abolition movement of the North. Of course, we all know how that played out.

Joe Meek was born in Virginia in 1810. He was a friendly young man, with a great sense of humor, but he had too much rambunctious energy to do well in school. He just couldn’t sit still well enough to focus on his studies. Finally, at 16 years old and illiterate, Meek gave up on school and moved west to join two of his brothers in Missouri. Still, he didn’t give up on all of his learning, just the formal learning. In later years, he taught himself to read and write, but his spelling and grammar remained “highly original” throughout his life.

Joe Meek was born in Virginia in 1810. He was a friendly young man, with a great sense of humor, but he had too much rambunctious energy to do well in school. He just couldn’t sit still well enough to focus on his studies. Finally, at 16 years old and illiterate, Meek gave up on school and moved west to join two of his brothers in Missouri. Still, he didn’t give up on all of his learning, just the formal learning. In later years, he taught himself to read and write, but his spelling and grammar remained “highly original” throughout his life.

Meek seemed to flourish in the West. It appears that he had found his calling, and in early 1829, he joined William Sublette’s ambitious expedition to begin fur trading in the Far West. Meek traveled throughout the West for the next decade. For him there was nothing greater than the adventure and independence of the mountain man life. Meek, the picture of a mountain man, at 6 feet 2 inches tall, and heavily bearded became a favorite character at the annual mountain-men rendezvous. The others loved to listen to his humorous and often exaggerated stories of his wilderness adventures. The truth is, I’m sure many people would have loved to hear about the adventures of the mountain man, especially this one, who was so unique. Like most mountain men, Meek was a renowned grizzly bear hunter. I suppose his stories of his hunting escapades could have been exaggerations, it’s hard to say. Meek claimed he liked to “count coup” on the dangerous animals before killing them, a variation on a Native American practice in which they shamed a live human enemy by tapping them with a long stick. To tap a grizzly bear with a stick, before the attempted kill, took either courage…or stupidity. Meek also claimed that he had wrestled an attacking grizzly with his bare hands before finally sinking a tomahawk into its brain. I suppose that if a grizzly bear attacked you, you would have no choice but to fight for your life, with your bare hands. Having the forethought to go for your tomahawk would be…well, amazing. Most people would try to cover their heads, and hope for the best. Still, that wouldn’t do much good. In a bear attack, you had better fight with everything you have, if you want to live. Maybe  mountain men spent a lot of time considering the possibility of an attack, and practicing in their head exactly how they would handle it.

mountain men spent a lot of time considering the possibility of an attack, and practicing in their head exactly how they would handle it.

Meek soon established good relations with many Native Americans, effectively melding with the Indians. He even married three Native American women, including the daughter of a Nez Perce chief. Now, that didn’t mean that he didn’t fight with the tribes on occasion, or at least the tribes who were hostile to the incursion of the mountain men into their territories. Meek intended to fight for his right to be on the land, the same as the Indians. In the spring of 1837, Meek was nearly killed by a Blackfeet warrior who was taking aim with his bow while Meek tried to reload his Hawken rifle. In the end, the warrior nervously dropped his first arrow while drawing the bow, and Meek had time to reload and shoot. The warrior’s fumble cost him his life, while saving Meek’s life.

After a great run as a mountain man, Meek recognized that the golden era of the free trappers was coming to a close. He began making plans to find another form of income. He joined with another mountain man, and along with his third wife, he guided one of the first wagon trains to cross the Rockies on the Oregon Trail. Once he arrived in Oregon, Meek fell in love with the lush Willamette Valley of western Oregon. He settled down and became a farmer, and actively encouraged other Americans to join him. Of course, more White men on what had been Indian lands, came with safety issued. Meek led a delegation to Washington DC to ask for military protection from Native American attacks and territorial status for Oregon in 1847. Though he arrived “ragged,  dirty, and lousy,” Meek became a bit of a celebrity in the capitol. Not used to the ways of mountain men, the Easterners truly enjoyed the rowdy good humor Meek showed in proclaiming himself the “envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary from the Republic of Oregon to the Court of the United States.” His enthusiasm prompted Congress to making Oregon an official American territory and Meek a US marshal. I wonder if he was shocked by his new role.

dirty, and lousy,” Meek became a bit of a celebrity in the capitol. Not used to the ways of mountain men, the Easterners truly enjoyed the rowdy good humor Meek showed in proclaiming himself the “envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary from the Republic of Oregon to the Court of the United States.” His enthusiasm prompted Congress to making Oregon an official American territory and Meek a US marshal. I wonder if he was shocked by his new role.

He might have been shocked, but Meek embraced his new role. He returned to Oregon and became heavily involved in politics, eventually founded the Oregon Republican Party. After his years of service, he retired to his farm, and on June 20, 1875, at the age of 65, Meek passed away. With his passing the world lost a skilled practitioner of the frontier art of the tall tale. It is said that his life was nearly as adventurous as his stories claimed, but there is no sure line to tell what was real and what was tall tale.

Captain John Mason was an English-born settler, soldier, commander, and Deputy Governor of the Connecticut Colony. While most people want to be remembered for the great things they did during their lives, Captain Mason will always be remembered for something else…being the leader of the massacre of the Pequot Tribe of Native Americans in southeast Connecticut. The group, led by Mason was a group of Puritan settlers and Indian allies, who combined to attack a Pequot Fort in an event known as the Mystic Massacre. The Mystic Massacre took place on May 26, 1637, during the Pequot War, when Connecticut colonizers and their Narragansett and Mohegan allies set fire to the Pequot Fort near the Mystic River. With the fire raging, they shot anyone who tried to escape the wooden palisade fortress, effectively murdering most of the village. In all, there were between 400 and 700 Pequot civilians killed during the massacre. The only Pequot survivors were warriors who were away in a raiding party with their sachem (chief), Sassacus.

Captain John Mason was an English-born settler, soldier, commander, and Deputy Governor of the Connecticut Colony. While most people want to be remembered for the great things they did during their lives, Captain Mason will always be remembered for something else…being the leader of the massacre of the Pequot Tribe of Native Americans in southeast Connecticut. The group, led by Mason was a group of Puritan settlers and Indian allies, who combined to attack a Pequot Fort in an event known as the Mystic Massacre. The Mystic Massacre took place on May 26, 1637, during the Pequot War, when Connecticut colonizers and their Narragansett and Mohegan allies set fire to the Pequot Fort near the Mystic River. With the fire raging, they shot anyone who tried to escape the wooden palisade fortress, effectively murdering most of the village. In all, there were between 400 and 700 Pequot civilians killed during the massacre. The only Pequot survivors were warriors who were away in a raiding party with their sachem (chief), Sassacus.

Prior to the massacre, the Pequot tribe were the dominate Native American tribe in southeast Connecticut, but  with the massacre, came the end of an era where that was concerned. The massacre was brutal and heinous and should have been met with severe punishment, but at that time in history, the Native Americans were not particularly valued among the people of the colonies. In fact, the Native Americans were probably viewed as the intruders, and not the natives. As more and more Puritans from Massachusetts Bay spread into Connecticut, the conflicts with the Pequots increased. The tribe centered on the Thames River in southeastern Connecticut, and by the spring of 1637, the Pequot tribe killed 13 English colonists and traders. That was when Massachusetts Bay Governor John Endecott organized a large military force to punish the Indians, who were only trying to protect what they saw as theirs. On April 23, 1637, with pressure mounting, 200 Pequot warriors responded defiantly to the colonial mobilization by attacking a Connecticut settlement, killing six men and three women and taking two girls away.

with the massacre, came the end of an era where that was concerned. The massacre was brutal and heinous and should have been met with severe punishment, but at that time in history, the Native Americans were not particularly valued among the people of the colonies. In fact, the Native Americans were probably viewed as the intruders, and not the natives. As more and more Puritans from Massachusetts Bay spread into Connecticut, the conflicts with the Pequots increased. The tribe centered on the Thames River in southeastern Connecticut, and by the spring of 1637, the Pequot tribe killed 13 English colonists and traders. That was when Massachusetts Bay Governor John Endecott organized a large military force to punish the Indians, who were only trying to protect what they saw as theirs. On April 23, 1637, with pressure mounting, 200 Pequot warriors responded defiantly to the colonial mobilization by attacking a Connecticut settlement, killing six men and three women and taking two girls away.

Then on May 26, 1637, everything exploded when, two hours before dawn, the Puritans and their Indian allies marched on the Pequot village at Mystic, slaughtering all but a handful of its inhabitants. Following that attack, Captain Mason attacked another Pequot village on June 5, 1637, this one near what is now Stonington, and again the Indian defenseless inhabitants, were defeated and massacred. In a third attack on July 28, 1637, Mason and his men massacred a village near what is now Fairfield, and the Pequot War finally came to an end. Most of the surviving Pequot were sold into slavery, though a handful escaped to join other southern New England tribes.

Then on May 26, 1637, everything exploded when, two hours before dawn, the Puritans and their Indian allies marched on the Pequot village at Mystic, slaughtering all but a handful of its inhabitants. Following that attack, Captain Mason attacked another Pequot village on June 5, 1637, this one near what is now Stonington, and again the Indian defenseless inhabitants, were defeated and massacred. In a third attack on July 28, 1637, Mason and his men massacred a village near what is now Fairfield, and the Pequot War finally came to an end. Most of the surviving Pequot were sold into slavery, though a handful escaped to join other southern New England tribes.

Every time I hear about a lost treasure, I wonder how many such treasures there are around the world. Some of these treasures are most likely lost forever, and one of those (so far anyway) is “The Old Spanish Treasure” which isn’t a treasure in a tropical, mysterious location from a long-ago shipwreck. Legend has it that the treasure is located in “The Old Spanish Treasure Cave,” which is actually located along the Missouri-Arkansas border. The location in and of itself, makes me wonder why no one has ever recovered the treasure.

Every time I hear about a lost treasure, I wonder how many such treasures there are around the world. Some of these treasures are most likely lost forever, and one of those (so far anyway) is “The Old Spanish Treasure” which isn’t a treasure in a tropical, mysterious location from a long-ago shipwreck. Legend has it that the treasure is located in “The Old Spanish Treasure Cave,” which is actually located along the Missouri-Arkansas border. The location in and of itself, makes me wonder why no one has ever recovered the treasure.

Apparently, about 400 years ago, Spanish conquistadors headed north in the dead of winter, raiding Native American villages as they went. During the raids, they accumulated a great amount of treasure, but the winter was raging, and they needed a place to get out of the cold. So, the conquistadors took refuge in a large cave. Of  course, they thought they were alone, but that couldn’t have been further from the truth. The Native Americans saw their campfire smoke coming out of a natural chimney at the top of the cave. Taking their revenge, the Native Americans attacked the conquistadors, leaving only one survivor.

course, they thought they were alone, but that couldn’t have been further from the truth. The Native Americans saw their campfire smoke coming out of a natural chimney at the top of the cave. Taking their revenge, the Native Americans attacked the conquistadors, leaving only one survivor.

Somehow keeping his wits about him, the survivor sealed all but one entrance and drew two maps…one on parchment, and one etched into a limestone rock. While the rock bearing the map was recovered, the treasure has yet to be found. The location of the cave is known, and I’m sure it and the map have been scoured repeatedly, but the survivor hid his treasure well. It almost makes me wonder if he hid it at all. Maybe he just took it with him or went back for it soon after it was hidden, and then simply left the map to throw people off the trail.

The cave was sealed up until it was re-discovered in 1885 by an old Spaniard from Madrid. As the story goes, old Spaniard the legend apparently led him to two maps…one on a tree, and another on a rock. Neither these maps nor the treasure, estimated today at 40 million dollars, have ever been found, but there have been a number of artifacts found, like helmets, pieces of armor, and weapons from the period. Some have even claimed to have found a few gold coins, but there is no proof of that. The Spaniard was ill, and so did not stay long. Other people continued to search for the treasure for many years, but to no avail. To this day, the elusive treasure remains hidden, and I suppose it always will.

The cave was sealed up until it was re-discovered in 1885 by an old Spaniard from Madrid. As the story goes, old Spaniard the legend apparently led him to two maps…one on a tree, and another on a rock. Neither these maps nor the treasure, estimated today at 40 million dollars, have ever been found, but there have been a number of artifacts found, like helmets, pieces of armor, and weapons from the period. Some have even claimed to have found a few gold coins, but there is no proof of that. The Spaniard was ill, and so did not stay long. Other people continued to search for the treasure for many years, but to no avail. To this day, the elusive treasure remains hidden, and I suppose it always will.

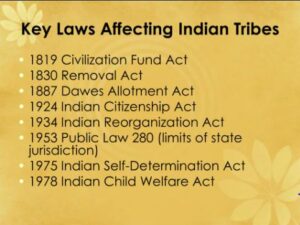

When people allow fear to enter into their thinking, unfortunate and sometimes horrific things can happen. That really was the case, I believe, with the American settlers and the Native Americans. I’m not saying that the treatment of the Indians was without blame, because that is just not the case, but the wars that took place left the American settlers afraid of the Indians, and some people even decided that we needed to basically, “teach it out of them” or change the way the children thought so we could change a generation. It sounds a lot like what is being attempted in our schools today, if you ask me.

When people allow fear to enter into their thinking, unfortunate and sometimes horrific things can happen. That really was the case, I believe, with the American settlers and the Native Americans. I’m not saying that the treatment of the Indians was without blame, because that is just not the case, but the wars that took place left the American settlers afraid of the Indians, and some people even decided that we needed to basically, “teach it out of them” or change the way the children thought so we could change a generation. It sounds a lot like what is being attempted in our schools today, if you ask me.

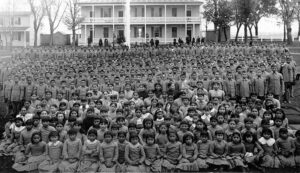

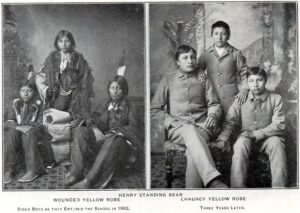

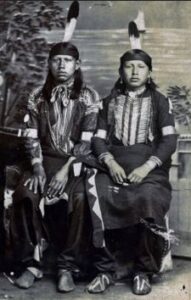

For over a century, the US government actually went in and took Native American children from their families and forced them to attend Indian boarding schools. The idea was to separate the Indian traditions, language, and culture from these children, so they would become a “man worth saving,” because they thought the Indians had no value. They even recruited the missionaries in their endeavor, with the passing of the Civilization Fund Act of 1819, which encouraged missionaries to educate Native American children in the ways of the white man. In reality, this plan set the stage for eventual forced removal of children from their parents, so the parents could no longer have a say in their education, or an influence in their lives. In 1879, Captain Richard Henry Pratt opened the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. The whole purpose of the school, according to Pratt, was to “kill the Indian, and save the man.”

The schools mistreated the children, because they didn’t want to comply, didn’t understand what was asked of them, or they were just plain scared. Scholar Margaret Archuleta explained, “Not only were children removed from their parents, often forcibly, but they had their mouths washed out with lye soap when they spoke their Native languages.” A 1902 government order even argued long hair and other traditional customs slowed “the advancement they are making in civilization.” These poor children were stripped of their heritage, their families, their traditions, and their right to live a free life of their own choosing.

You might think that this barbaric act was something that was practiced just in the early days of this country and into the Indian Wars era, but these boarding schools actually continued until 1978!! At that time, Congress

finally passed the Indian Child Welfare Act, which also addressed the practice of forcible adoption of Native American children. From that time on, Native American families were once again able to practice their own traditions and culture and speak their own language. I wonder just how much of their heritage was lost forever in the 159 years that the children spent in the custody of the American government.

finally passed the Indian Child Welfare Act, which also addressed the practice of forcible adoption of Native American children. From that time on, Native American families were once again able to practice their own traditions and culture and speak their own language. I wonder just how much of their heritage was lost forever in the 159 years that the children spent in the custody of the American government.

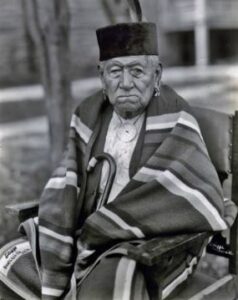

During the years when America was expanding very quickly, many Native American nations were placed on reservations, and the land they had previously lived on was taken from them…often by force, but sometimes by choice. Some Indians saw the writing on the wall and chose to go to the reservation so their people could survive. Those who didn’t found themselves in multiple battles that often ended in death.

During the years when America was expanding very quickly, many Native American nations were placed on reservations, and the land they had previously lived on was taken from them…often by force, but sometimes by choice. Some Indians saw the writing on the wall and chose to go to the reservation so their people could survive. Those who didn’t found themselves in multiple battles that often ended in death.

One group, the Osage Tribe made the decision to abandon their lands in Missouri and Aransas, giving it to the White Man’s Government, in exchange for the reservation in Oklahoma that was offered to them. I’m sure there were those within the tribe who were not happy with the decision that was made, but time would prove that it was the wisest decision to make. The decision made at that time, would later make them one of the wealthiest surviving Native American nations. The Osage Tribe was, at one time, the largest tribe of the Southern Sioux people. They occupied what are now the states of Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska. This sophisticated tribe of people surprised the first Anglo explorers and settlers. When the settlers moved into the region, they found this Native American tribe living in more or less permanent villages made of sturdy earthen and log lodges. They really didn’t expect these people, whom they considered to be primitive, to be in such modern-day (for the times anyway) homes. The Osage Tribe is related to the Quapaw, Ponca, Omaha, and Kansa peoples. Like their cousins the Plains Indians, the Osage Tribe hunted buffalo and wild game, but they also raised crops to supplement their diets. They were really forward thinking, which was unusual for the times.

Americans found it much easier to understand and negotiate with the Southern Sioux, even though they often warred among themselves. They felt like they could understand the Southern Sioux much easier, because of their more sedentary ways…thing that the more nomadic Northern Sioux just didn’t make sense in that they just seemed to wander around. The White Man didn’t understand that kind of thinking. Maybe it was the more permanent homes offered by the American negotiators, that convinced the Osage Tribe to abandon their traditional lands and move peacefully to a reservation in southern Kansas in 1810. Unfortunately, that would not be the move that made the White Man happy, so when American settlers began to covet the Osage reservation in Kansas, the tribe agreed to yet another move, relocating to what is now Osage County, Oklahoma, in 1872.

While the American settlers found it easier to work with the Osage Tribe and the Southern Sioux, they were not always truly fair with them. The American settlers constantly pressured the government to push Native Americans off valuable lands and onto marginal reservations. Unfortunately, this practice was all too common throughout the history of western settlement. Most tribes were devastated by these relocations, including some of the Southern Sioux tribes like the Kansa, whose population of 1,700 was reduced to only 194 following their disastrous relocation to a 250,000-acre reservation in Kansas. Nevertheless, the Osage tribe, proved unusually

successful in adapting to the demands of living in a world dominated by Anglo-Americans. Of course, a big part of their success and wealth is due in part to the presence of large reserves of oil and gas on their Oklahoma reservation, as well as the effective management of the grazing contracts set up with the Anglos. During the twentieth century, the Osage amassed enormous wealth from their oil and gas deposits, eventually becoming the wealthiest tribe in North America.

successful in adapting to the demands of living in a world dominated by Anglo-Americans. Of course, a big part of their success and wealth is due in part to the presence of large reserves of oil and gas on their Oklahoma reservation, as well as the effective management of the grazing contracts set up with the Anglos. During the twentieth century, the Osage amassed enormous wealth from their oil and gas deposits, eventually becoming the wealthiest tribe in North America.

The other day, while reading an article about notable Native Americans, I came across a name that was familiar to me, but really didn’t seem like a Native American name. The name was Renville, the same name as my grand-nephew, James Renville. Immediately, I wondered if there might be a connection between Chief Gabriel Renville and my grand-nephew. The search didn’t take very long, before I had my answer. Gabriel Renville is my grand-nephew, James’ 1st cousin 7 times removed. I find that to be extremely amazing to think that James is related to an Indian chief. With that information, I wanted to fine out more abut this man.

The other day, while reading an article about notable Native Americans, I came across a name that was familiar to me, but really didn’t seem like a Native American name. The name was Renville, the same name as my grand-nephew, James Renville. Immediately, I wondered if there might be a connection between Chief Gabriel Renville and my grand-nephew. The search didn’t take very long, before I had my answer. Gabriel Renville is my grand-nephew, James’ 1st cousin 7 times removed. I find that to be extremely amazing to think that James is related to an Indian chief. With that information, I wanted to fine out more abut this man.

Chief Gabriel Renville was a mixed-blood Santee Sioux—his father was half French and his mother half-Scottish. He was born in April of 1825 at Big Stone Lake, South Dakota. Renville was the treaty chief of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Santee tribes and signed the 1867 treaty, which established the boundaries of the Lake Traverse Reservation. One source called him a Champion of Excellence.

He was careful to protect his people as much as he could, and was also instrumental in saving the lives of many white captives. During the 1862 Uprising, Renville opposed Little Crow and was influential in keeping many of the Santee out of the war. He lost a large amount of property, including horses appropriated by the hostile savages, or destroyed in consequence of his position to their murderous course. Renville served as chief of scouts for General Sibley during the campaign against the Sioux in 1863.

Even though Chief Renville was an ally of the whites, it didn’t help him when he settled on the reservation. The government agent there, Moses N. Adams, considered him hostile. Renville was the leader of the “scout party” which was in conflict with the “good church” Indians. I’m sure that was common in those days. Renville preserved many of the traditional Santee customs of polygamy and dancing, and he ignored Christianity, but he  was not opposed to economic progress and he and his followers became successful farmers on the reservation. However, the Sisseton agent favored the “church” Indians.

was not opposed to economic progress and he and his followers became successful farmers on the reservation. However, the Sisseton agent favored the “church” Indians.

Renville and other leaders of the traditional Indians accused Adams of discriminating against them in the disposition of supplies and equipment. He said Adams favored the idle church-goers instead of encouraging them to work….a situation not unlike the current welfare system. Agent Adams considered Renville a detriment and removed the chief form the reservation executive board which Adams had organized to carry out his policies. It was a move that was considered extreme. In 1874 Renville was finally successful in securing a government investigation of the Adam’s activities. The outcome of the investigation was an official censure of Adams. Chief Renville continued to practice the old Santee customs, yet he encouraged the Indians to farm. This progressive influence was greatly missed after his death in August 1892.

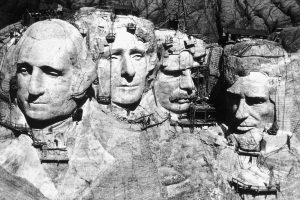

When a construction project begins, it usually takes a matter of a few months to complete. That is not how it works when carving a large sculpture, such as Mount Rushmore. Mount Rushmore National Memorial is a sculpture carved into the granite face of Mount Rushmore, a batholith in the Black Hills in Keystone, South Dakota, United States. It was the vision of Doane Robinson, who thought that carving the faces of famous people in the Granite of the Black Hills region, would bring tourists to the region. Robinson’s vision has proven to be an amazing success. His original idea was to put the sculpture in the area of the Needles, but the chosen sculptor, Gutzon Borglum rejected the idea because of the poor quality of the granite, and strong opposition from the Native American Groups in the area. I’m glad it didn’t go in the needles area, because they have a beauty all their own, and it would have been a shame to change them.

When a construction project begins, it usually takes a matter of a few months to complete. That is not how it works when carving a large sculpture, such as Mount Rushmore. Mount Rushmore National Memorial is a sculpture carved into the granite face of Mount Rushmore, a batholith in the Black Hills in Keystone, South Dakota, United States. It was the vision of Doane Robinson, who thought that carving the faces of famous people in the Granite of the Black Hills region, would bring tourists to the region. Robinson’s vision has proven to be an amazing success. His original idea was to put the sculpture in the area of the Needles, but the chosen sculptor, Gutzon Borglum rejected the idea because of the poor quality of the granite, and strong opposition from the Native American Groups in the area. I’m glad it didn’t go in the needles area, because they have a beauty all their own, and it would have been a shame to change them.

They settled on Mount Rushmore, which also has the advantage of facing southeast for maximum sun exposure, which makes the faces of our presidents stand out in an amazing way. Robinson wanted it to feature American West heroes like Lewis and Clark, Red Cloud, and Buffalo Bill Cody, but Borglum decided the sculpture should have broader appeal and chose the four presidents. Borglum created the sculpture’s design and oversaw the project’s execution from 1927 to 1941 with the help of his son, Lincoln Borglum. When I think of the years it too to complete the sculpture, I wonder if it was what was expected, or just the way it came down. Mount Rushmore features 60-foot sculptures of the heads of four United States presidents…George Washington (1732–1799), Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), and Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865). After securing federal funding through the enthusiastic sponsorship of “Mount Rushmore’s great political patron” US Senator Peter Norbeck, construction on the memorial began in 1927, and the presidents’ faces were completed between 1934 and 1939. Upon Gutzon Borglum’s death in March 1941, his son Lincoln Borglum took over as leader of the construction project. Each president was originally to be depicted from head to waist.

The memorial park covers 1,278.45 acres and is 5,725 feet above sea level, and while the sculpture work officially ended on October 31, 1941, due to lack of funding and the very real possibility of a United States entrance into World War II. Mount Rushmore has become an iconic symbol of the United States, and it has

appeared in works of fiction, as well as being discussed or depicted in other popular works. It has also been featured a number of movies. It attracts over two million visitors annually. It’s amazing to me that what started out to be a tourist attraction, quickly became a must see place for every patriotic American. My husband and I love to go to the Black Hills, and with the close proximity to our Casper, Wyoming home, we take a week every summer to go and enjoy the beauty and patriotism that now resides there.

appeared in works of fiction, as well as being discussed or depicted in other popular works. It has also been featured a number of movies. It attracts over two million visitors annually. It’s amazing to me that what started out to be a tourist attraction, quickly became a must see place for every patriotic American. My husband and I love to go to the Black Hills, and with the close proximity to our Casper, Wyoming home, we take a week every summer to go and enjoy the beauty and patriotism that now resides there.