nasa

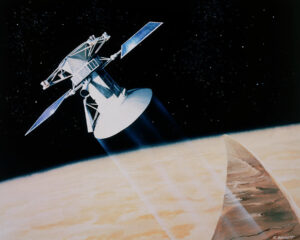

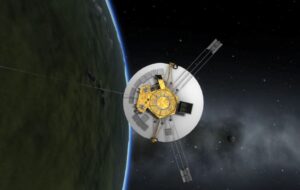

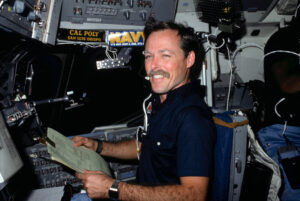

In the height of space travel, NASA decided to set up a mission to take pictures of Venus. The planet is always shrouded in a layer of clouds, with an extremely thick carbon dioxide atmosphere. When looking at Venus in visible light, those clouds are all you would see. That said, even a “flyby” would not give a good view of the planet, plus it would take a long time to get there, so it wasn’t feasible for a manned mission. Nevertheless, a mission was set up in March of 1988, for the purpose of “checking it out.” It was announced by NASA that astronauts Walker, Grabe, Lee, Thagard, and Cleave would be the crew of the STS-30 mission to release the Magellan spacecraft for the flight planned for late April 1989. Thagard had flown twice before, on STS-7 in June 1983 and the STS-51B Spacelab 3 mission in April-May 1985. Walker, Grabe, and Cleave had each flown once before, on STS-51A, STS-51J, and STS-61B, respectively. STS-30 would be Lee’s first trip into space. Walker and Thagard joined NASA in the astronaut class of 1978, Grabe and Cleave joined in 1980, and Lee in 1984. The mission would take four days, during which they would deploy Magellan and its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) on the first flight day. There was a 29-day window for the deployment of Magellan, as dictated by the alignments of Venus and Earth to achieve the proper trajectory for the journey to its destination. Once it was released, their job, as far as Magellan was essentially over.

In the height of space travel, NASA decided to set up a mission to take pictures of Venus. The planet is always shrouded in a layer of clouds, with an extremely thick carbon dioxide atmosphere. When looking at Venus in visible light, those clouds are all you would see. That said, even a “flyby” would not give a good view of the planet, plus it would take a long time to get there, so it wasn’t feasible for a manned mission. Nevertheless, a mission was set up in March of 1988, for the purpose of “checking it out.” It was announced by NASA that astronauts Walker, Grabe, Lee, Thagard, and Cleave would be the crew of the STS-30 mission to release the Magellan spacecraft for the flight planned for late April 1989. Thagard had flown twice before, on STS-7 in June 1983 and the STS-51B Spacelab 3 mission in April-May 1985. Walker, Grabe, and Cleave had each flown once before, on STS-51A, STS-51J, and STS-61B, respectively. STS-30 would be Lee’s first trip into space. Walker and Thagard joined NASA in the astronaut class of 1978, Grabe and Cleave joined in 1980, and Lee in 1984. The mission would take four days, during which they would deploy Magellan and its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) on the first flight day. There was a 29-day window for the deployment of Magellan, as dictated by the alignments of Venus and Earth to achieve the proper trajectory for the journey to its destination. Once it was released, their job, as far as Magellan was essentially over.

STS-30 lifted off on May 4, 1989, utilizing space shuttle Atlantis, which was on its third space flight. Of course, STS-30 lifted off from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Its five-person crew included Commander David M Walker, Pilot Ronald J Grabe, and Mission Specialists Mark C Lee, Norman E Thagard, and Mary L Cleave. They flew a four-day mission that deployed the Magellan spacecraft, which was then managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, to study Venus. This mission would unite NASA’s human and interplanetary spaceflight programs. It also marked the first US planetary launch since 1978. The astronauts successfully deployed Magellan and its upper stage on their first day in space, sending the spacecraft off on its 15-month journey to Venus. I can imagine that it was an exciting venture for them.

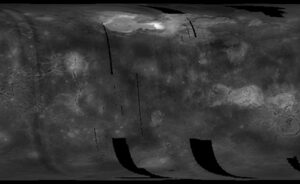

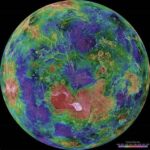

Once Magellan arrived at the cloud-shrouded planet, it spent four years mapping Venus in unprecedented detail. The mission vastly increased human knowledge of the planet. The Magellan spacecraft arrived at Venus on August 10, 1990. Using radar imaging, Magellan began its primary goal of mapping the surface of Venus. The radar imaging was able to “peek” through the thick clouds which made visual observation difficult. While there, Magellan made the first global map of the surface of Venus and global maps of the planet’s gravity field. It was inserted into a near-polar elliptical orbit and continued its mission for several years. After its journey to Venus, the Magellan spacecraft, finally arrived at Venus in 1990. It then made the first global map of the surface of Venus as well as global maps of the planet’s gravity field. NASA was quite surprised at the findings

Magellan produced, including the fact that it had a relatively young planetary surface that was probably formed by lava flows from planet-wide volcanic eruptions. After completing its four-year flight mission, NASA deliberately plunged the Magellan spacecraft to the surface of Venus in October 1994 to gather data on the planet’s atmosphere before it ceased operations. It marked the first time an operating planetary spacecraft had been intentionally crashed.

Magellan produced, including the fact that it had a relatively young planetary surface that was probably formed by lava flows from planet-wide volcanic eruptions. After completing its four-year flight mission, NASA deliberately plunged the Magellan spacecraft to the surface of Venus in October 1994 to gather data on the planet’s atmosphere before it ceased operations. It marked the first time an operating planetary spacecraft had been intentionally crashed.

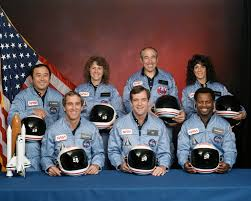

The Space Shuttle Challenger mission, named STS-51-L, was the twenty-fifth Space Shuttle flight and the tenth flight of Challenger. The crew was announced on January 27, 1985, and was commanded by Dick Scobee. Michael Smith was assigned as the pilot, and the mission specialists were Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, and Ronald McNair. The two payload specialists were Gregory Jarvis, who was assigned to conduct research for the Hughes Aircraft Company, and Christa McAuliffe, who flew as part of the Teacher in Space Project. The mission was originally scheduled for July 1985, but was delayed to November and then to January 1986. The mission was scheduled to launch on January 22, but was delayed until January 28, 1986. This was definitely a “less than ideal” situation. Delay after delay, maybe should have raised a serious red flag, but somehow, it did not. At least not to the people who could have changed the outcome.

The Space Shuttle Challenger mission, named STS-51-L, was the twenty-fifth Space Shuttle flight and the tenth flight of Challenger. The crew was announced on January 27, 1985, and was commanded by Dick Scobee. Michael Smith was assigned as the pilot, and the mission specialists were Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, and Ronald McNair. The two payload specialists were Gregory Jarvis, who was assigned to conduct research for the Hughes Aircraft Company, and Christa McAuliffe, who flew as part of the Teacher in Space Project. The mission was originally scheduled for July 1985, but was delayed to November and then to January 1986. The mission was scheduled to launch on January 22, but was delayed until January 28, 1986. This was definitely a “less than ideal” situation. Delay after delay, maybe should have raised a serious red flag, but somehow, it did not. At least not to the people who could have changed the outcome.

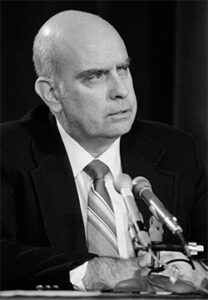

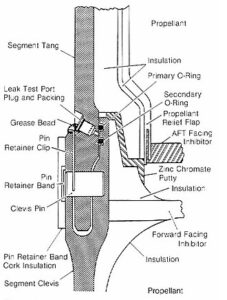

One man…Roger Boisjoly knew that the Challenger space shuttle might fail catastrophically at any time. There may have been others I suppose, but none that chose to try to take action. Boisjoly knew that every mission was an accident waiting to happen. Knowing that, he tried to stop the launch on January 28, 1986. He had a definite sick feeling about this mission, but NASA refused to acknowledge his objections. That fact amazes me!! Boisjoly was a rocket engineer who worked for a company that NASA contracted with. He had noticed that the Challenger’s booster rockets had a major design flaw. Their elastic seals had a tendency to stiffen and unseal in cold weather. I’m sure that most of NASA simply took for granted that there would not be much cold weather in Florida. Nevertheless, on this occasion, the Challenger was scheduled for a winter launch. The time had come, and Boisjoly knew that the temperatures would be too low for the booster rocket seals to handle, even in Florida. He convinced colleagues at his engineering company to formally recommend NASA delay the launch. They did, but NASA ignored that recommendation. It was a life altering, or life ending decision on NASA’s part. Most of us know that the rest is history. The launch took place, the seals failed, and the Challenger exploded less than two minutes after it launched. That day, because of the foolish stubbornness and arrogance of NASA, seven people lost their lives. The air temperature on that January 28 was predicted to be a record-low for a Space Shuttle launch. The air temperature was forecast to drop to 18° F overnight before rising to 22° F at 6:00am and 26° F at the scheduled launch time of 9:38am. For most of us, those temperatures wouldn’t seem

to be so severe, but for that little seal, it was very severe. Why couldn’t they have swallowed their pride, and postponed a little longer until the temperature warmed a bit. Were we really in that big a rush to start that mission, that we were willing risk the lives of seven people in the attempt. I love the space program and all that it has accomplished, but the people who made that choice that day were foolish and selfish.

to be so severe, but for that little seal, it was very severe. Why couldn’t they have swallowed their pride, and postponed a little longer until the temperature warmed a bit. Were we really in that big a rush to start that mission, that we were willing risk the lives of seven people in the attempt. I love the space program and all that it has accomplished, but the people who made that choice that day were foolish and selfish.

The Controlled Impact Demonstration, also known as “the Crash in the Desert” was a joint project between NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The idea was to intentionally crash a remotely controlled Boeing 720 airplane in order to acquire data and test new technologies to aid passenger and crew survival. As we all know, airplane crashes, often bring fatalities. Still, there have been a number of airplane crashes in which all or most of the plane’s occupants survived the crash. The point of “the crash in the desert” was to learn from the vent, and hopefully make a way for more people to survive the crash.

The Controlled Impact Demonstration, also known as “the Crash in the Desert” was a joint project between NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The idea was to intentionally crash a remotely controlled Boeing 720 airplane in order to acquire data and test new technologies to aid passenger and crew survival. As we all know, airplane crashes, often bring fatalities. Still, there have been a number of airplane crashes in which all or most of the plane’s occupants survived the crash. The point of “the crash in the desert” was to learn from the vent, and hopefully make a way for more people to survive the crash.

The Controlled Impact Demonstration took more than four years of preparation by NASA Ames Research Center, Langley Research Center, Dryden Flight Research Center, the FAA, and General Electric to pull off. Then, because obviously they did not have an unlimited supply of planes, they held several test runs to make sure they had the right “crash” conditions to learn the most about crashes. Finally, on December 1, 1984, the plane was actually crashed. The test went pretty much according to plan and produced a large fireball that required more than an hour to extinguish. With that in mind, a casual observer would assume that everyone would have died, but the FAA concluded that about one-quarter of the passengers would have survived!! It also determined that the antimisting kerosene test fuel did not sufficiently reduce the risk of fire. Antimisting kerosene (AMK) is “a jet fuel containing an antimisting additive. This additive, a high-molecular-weight polymer, causes the fuel to resist atomization and liquid shear forces, which also affect flow characteristics in the engine fuel system.” Finally, it determined that several changes to equipment in the passenger compartment of aircraft were needed…which is probably one of the most important findings of the demonstration. NASA also concluded that a head-up display and microwave landing system would have definitely helped the pilot more safely fly the aircraft.

On the morning of December 1, 1984, the test aircraft took off from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Once aloft, the plane made a left-hand departure and climbed to an altitude of 2,300 feet. The plane was remotely flown by NASA research pilot Fitzhugh Fulton from the NASA Dryden Remotely Controlled Vehicle Facility. All fuel tanks were filled with a total of 76,000 pounds of AMK and all engines ran from start-up to impact. The total flight time was 9 minutes on the modified Jet-A. It then began a descent-to-landing along the roughly 3.8-degree glideslope to a specially prepared runway on the east side of Rogers Dry Lake, with the landing gear remaining retracted.

Passing the decision height of 150 feet above ground level (AGL), the airplane turned slightly to the right of the desired path, entering into a situation known as a Dutch roll. Slightly above that decision point at which the  pilot was to execute a “go-around” maneuver. There appeared to be enough altitude to maneuver back to the center-line of the runway. The aircraft was below the glideslope and below the desired airspeed. At this point, the data acquisition systems had been activated, and the plane was committed to impact. That situation had to have almost a strange feeling to it…that point of knowing that the plane was going to crash and knowing that the crash was exactly what you wanted it to do. Then the plane contacted the ground, left wing low, at full throttle, with its nose pointing to the left of the center-line. The original plan was that “the aircraft would land wings-level, with the throttles set to idle, and exactly on the center-line during the CID, thus allowing the fuselage to remain intact as the wings were sliced open by eight posts cemented into the runway (called “Rhinos” due to the shape of the “horns” welded onto the posts).” The Boeing 720 had a surprise in store for the researchers, when it landed askew. “One of the Rhinos sliced through the number 3 engine, behind the burner can, leaving the engine on the wing pylon, which does not typically happen in an impact of this type. The same rhino then sliced through the fuselage, causing a cabin fire when burning fuel was able to enter the fuselage.”

pilot was to execute a “go-around” maneuver. There appeared to be enough altitude to maneuver back to the center-line of the runway. The aircraft was below the glideslope and below the desired airspeed. At this point, the data acquisition systems had been activated, and the plane was committed to impact. That situation had to have almost a strange feeling to it…that point of knowing that the plane was going to crash and knowing that the crash was exactly what you wanted it to do. Then the plane contacted the ground, left wing low, at full throttle, with its nose pointing to the left of the center-line. The original plan was that “the aircraft would land wings-level, with the throttles set to idle, and exactly on the center-line during the CID, thus allowing the fuselage to remain intact as the wings were sliced open by eight posts cemented into the runway (called “Rhinos” due to the shape of the “horns” welded onto the posts).” The Boeing 720 had a surprise in store for the researchers, when it landed askew. “One of the Rhinos sliced through the number 3 engine, behind the burner can, leaving the engine on the wing pylon, which does not typically happen in an impact of this type. The same rhino then sliced through the fuselage, causing a cabin fire when burning fuel was able to enter the fuselage.”

“The cutting of the number 3 engine and the full-throttle situation was significant, as this was outside the test envelope. The number 3 engine continued to operate for approximately 1/3 of a rotation, degrading the fuel and igniting it after impact, providing a significant heat source. The fire and smoke took over an hour to extinguish. The CID impact was spectacular with a large fireball created by the number 3 engine on the right side, enveloping and burning the aircraft. From the standpoint of AMK the test was a major set-back. For NASA Langley, the data collected on crashworthiness was deemed successful and just as important.”

The actual impact proved that the antimisting additive they had tested was not going to prevent a post-crash fire in all situations, but the reduced intensity of the initial fire was attributed to the effect of the AMK. FAA investigators estimated that 23% to 25% of the aircraft’s full capacity of 113 people could have survived the crash. Now that is saying something, considering the way the crash looked to observers. “Time from slide-out to complete smoke obscuration for the forward cabin was 5 seconds; for the aft cabin, it was 20 seconds. Total time to evacuate was 15 and 33 seconds respectively, accounting for the time necessary to reach and open the doors and operate the slide.” The FAA instituted new flammability standards for seat cushions which required the use of fire-blocking layers as a result of analysis of the crash, resulting in seats which performed better than those in the test. From this crash demonstration, came the implementation of a standard requiring floor  proximity lighting to be mechanically fastened, due to the apparent detachment of two types of adhesive-fastened emergency lights during the impact. In addition, federal aviation regulations for flight data recorder sampling rates for pitch, roll, and acceleration were found to be insufficient. NASA determined that at the point of impact, the piloting task workload unusually high, which might have been reduced through the use of a heads-up display, the automation of more tasks, and a higher-resolution monitor. The use of a microwave landing system to improve tracking accuracy over the standard instrument landing system was also recommended. The Global Positioning System-based Wide Area Augmentation System came to fulfill this role.

proximity lighting to be mechanically fastened, due to the apparent detachment of two types of adhesive-fastened emergency lights during the impact. In addition, federal aviation regulations for flight data recorder sampling rates for pitch, roll, and acceleration were found to be insufficient. NASA determined that at the point of impact, the piloting task workload unusually high, which might have been reduced through the use of a heads-up display, the automation of more tasks, and a higher-resolution monitor. The use of a microwave landing system to improve tracking accuracy over the standard instrument landing system was also recommended. The Global Positioning System-based Wide Area Augmentation System came to fulfill this role.

The first official space flight occurred on April 12, 1961, when Soviet astronaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who, aboard the first successful crewed spaceflight, became the first human to journey into outer space. Traveling on Vostok 1, Gagarin completed one orbit of Earth on 12 April 1961. While that was the first official manned space flight, there were other times that man touched space.

The first official space flight occurred on April 12, 1961, when Soviet astronaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who, aboard the first successful crewed spaceflight, became the first human to journey into outer space. Traveling on Vostok 1, Gagarin completed one orbit of Earth on 12 April 1961. While that was the first official manned space flight, there were other times that man touched space.

The North American X-15 was an experimental US single seat rocket powered airplane that was taken aloft by a B-52 bomber acting as its “mother ship” and released to test extremely high speed and extremely high-altitude flight. The first such flight took place on June 8, 1959.

The hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft known as the North American X-15, was operated by the United States Air Force and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration as part of the X-plane series of experimental aircraft. While it didn’t exactly go into space, the X-15 set speed and altitude records in the 1960s, reaching the edge of outer space and returning with valuable data used in aircraft and spacecraft design, making it a precursor to the spacecraft of today. The X-15’s highest speed, 4,520 miles per hour , was achieved on October 3, 1967, when William J Knight flew at Mach 6.7 at an altitude of 102,100 feet or 19.34 miles. This set the official world record for the highest speed ever recorded by a crewed, powered aircraft, and it remains unbroken to this day.

While pilot, William Knight flew an all-time record speed of Mach 6.7 (4520 miles per hour), the fastest speed flown by a powered and manned piloted aircraft, in 1967, his flight wasn’t the first record setting flight in the X-15. This incredible speed was not even close to the maximum potential of the X-15. A typical commercial passenger jet flies at a speed of about 460 – 575 miles per hour, when cruising at about 36,000 feet, which figures to about 75-85% of the speed of sound. I can’t imagine going any faster than that, much less wrap my head around more than 4520 miles per hour!!

In 1963, pilot Joe Walker flew his X-15 into the history books by flying it to a record altitude of 67 miles and achieving a speed of almost Mach 5 (3794 miles per hour). While there is no sharp physical boundary that marks the end of atmosphere and the beginning of space, it is generally marked at the Karman line, and for purposes of space flight defined as an altitude of 60 miles, although some place the line at 50 miles above Earth’s mean sea level.

The X-15 program continued until 1968, when the rocket planes were retired. On notable pilot was Neil Armstrong, who was also the first man to walk on the Moon, of course. Armstrong made 7 flights in the speedy rocket plane. Also interesting to note is the fact that during the X-15 program, 12 pilots flew a combined 199 flights. Of the 12 pilots, 8

pilots flew a combined 13 flights that exceeded the altitude of 50 miles, thus qualifying these pilots as being astronauts!! Of those 13 flights, two (flown by the same civilian pilot) met the FAI (Féderátion Aéronautique Internationale) definition of 62 miles of outer space. The 5 Air Force pilots qualified for military astronaut wings immediately, while the 3 civilian pilots were eventually awarded NASA astronaut wings in 2005, 35 years after the last X-15 flight.

pilots flew a combined 13 flights that exceeded the altitude of 50 miles, thus qualifying these pilots as being astronauts!! Of those 13 flights, two (flown by the same civilian pilot) met the FAI (Féderátion Aéronautique Internationale) definition of 62 miles of outer space. The 5 Air Force pilots qualified for military astronaut wings immediately, while the 3 civilian pilots were eventually awarded NASA astronaut wings in 2005, 35 years after the last X-15 flight.

Thankfully, the NASA space program hasn’t had a great number of losses, but that doesn’t make any loss less devastating that any of the others. On February 1, 2003, just a little over 17 years after the Challenger disaster, the country was once again feeling like the Space Shuttle program was so safe that it was even mundane. Many people had no idea when the shuttle flights went up or came down. It wasn’t the nation’s fault, it’s just that like air travel, the Shuttle program was relatively save, but when disaster strikes, we are once again reminded…horrifically, that relatively save does not mean completely safe from an accident. People are prone to get comfortable when things are going well. We forget the bad times. Nevertheless, space travel is not accident proof, even if it has become relatively safe.

Thankfully, the NASA space program hasn’t had a great number of losses, but that doesn’t make any loss less devastating that any of the others. On February 1, 2003, just a little over 17 years after the Challenger disaster, the country was once again feeling like the Space Shuttle program was so safe that it was even mundane. Many people had no idea when the shuttle flights went up or came down. It wasn’t the nation’s fault, it’s just that like air travel, the Shuttle program was relatively save, but when disaster strikes, we are once again reminded…horrifically, that relatively save does not mean completely safe from an accident. People are prone to get comfortable when things are going well. We forget the bad times. Nevertheless, space travel is not accident proof, even if it has become relatively safe.

On that awful February 1st morning in 2003, we were once again jolted out of our comfort zones and thrust  back into the reality that the Shuttle program might have some serious flaws. Still, the Space Shuttle program was a long running and highly successful program, running from 1981 to 2011. During the course of the program, a total of 135 missions were flown, all launched from Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. During that period of time, the fleet logged 1,322 days, 19 hours, 21 minutes and 23 seconds of flight time. The first orbiter built, Enterprise, was used for atmospheric flight tests (ALT) but future plans to upgrade it to orbital capability were ultimately canceled. Originally, NASA built four fully operational orbiters…Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, and Atlantis. Of course, we know that Challenger and Columbia were destroyed in mission accidents in 1986 and 2003 respectively, killing a total of fourteen astronauts. A fifth operational orbiter, Endeavour, was built in 1991 to replace Challenger. In the end, it was decided that the shuttles were getting old and had too many flaws, so the Space Shuttle was retired from service upon the conclusion of STS-135 by Atlantis on July 21, 2011.

back into the reality that the Shuttle program might have some serious flaws. Still, the Space Shuttle program was a long running and highly successful program, running from 1981 to 2011. During the course of the program, a total of 135 missions were flown, all launched from Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. During that period of time, the fleet logged 1,322 days, 19 hours, 21 minutes and 23 seconds of flight time. The first orbiter built, Enterprise, was used for atmospheric flight tests (ALT) but future plans to upgrade it to orbital capability were ultimately canceled. Originally, NASA built four fully operational orbiters…Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, and Atlantis. Of course, we know that Challenger and Columbia were destroyed in mission accidents in 1986 and 2003 respectively, killing a total of fourteen astronauts. A fifth operational orbiter, Endeavour, was built in 1991 to replace Challenger. In the end, it was decided that the shuttles were getting old and had too many flaws, so the Space Shuttle was retired from service upon the conclusion of STS-135 by Atlantis on July 21, 2011.

It was a piece of foam insulation that would bring down the Columbia shuttle. It broke off and hit the leading edge of the wing. That small little bit of damage to the wing allowed hot gases to enter the wing causing it to  break up as the craft entered Earth’s atmosphere. During the breakup, debris and the bodies of the astronauts were strewn across the state of Texas. The breakup began over California at 8:53am, and by 8:59am, communication was lost. Mission Control began its disaster procedures at 9:12am. Lost in the disaster were Rick D Husband (Commander), William C McCool (Pilot), Michael P Anderson (Payload Commander), Ilan Ramon (Payload Specialist), Kalpana Chawla (an Indian-born aerospace engineer and a Mission Specialist), David M Brown (Mission Specialist), and Laurel Blair Salton Clark (Mission Specialist). Today, marks the 20th anniversary of that fateful day. Today, we honor those we lost.

break up as the craft entered Earth’s atmosphere. During the breakup, debris and the bodies of the astronauts were strewn across the state of Texas. The breakup began over California at 8:53am, and by 8:59am, communication was lost. Mission Control began its disaster procedures at 9:12am. Lost in the disaster were Rick D Husband (Commander), William C McCool (Pilot), Michael P Anderson (Payload Commander), Ilan Ramon (Payload Specialist), Kalpana Chawla (an Indian-born aerospace engineer and a Mission Specialist), David M Brown (Mission Specialist), and Laurel Blair Salton Clark (Mission Specialist). Today, marks the 20th anniversary of that fateful day. Today, we honor those we lost.

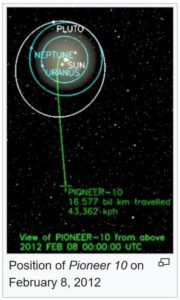

Many of us have seen shows about a spacecraft that got lost in space and is seen wandering around trying to make their way back. Of course, those shows are fiction, but if you were going to explore beyond our galaxy, you would most likely need to send some sort of probe or spaceship out into the far reaches of space to see what it’s like out there. If the empty probe can’t function out there, it’s very likely not a good idea to send a manned spaceship out there. That is what Nasa figured anyway, and so in 1972, Pioneer 10…originally designated Pioneer F, was launched into space. Pioneer 10 is an American space probe, manufactured by TRW Inc. It isn’t overly heavy, weighing just 569 pounds. Its first mission to the planet Jupiter was completed with its closest approach happening on Dec 3, 1973. At that point, Pioneer 10 became the first of five artificial objects to achieve the escape velocity needed to leave the Solar System. At that point, it became part of a space exploration project that was conducted by the NASA Ames Research Center in California.

Many of us have seen shows about a spacecraft that got lost in space and is seen wandering around trying to make their way back. Of course, those shows are fiction, but if you were going to explore beyond our galaxy, you would most likely need to send some sort of probe or spaceship out into the far reaches of space to see what it’s like out there. If the empty probe can’t function out there, it’s very likely not a good idea to send a manned spaceship out there. That is what Nasa figured anyway, and so in 1972, Pioneer 10…originally designated Pioneer F, was launched into space. Pioneer 10 is an American space probe, manufactured by TRW Inc. It isn’t overly heavy, weighing just 569 pounds. Its first mission to the planet Jupiter was completed with its closest approach happening on Dec 3, 1973. At that point, Pioneer 10 became the first of five artificial objects to achieve the escape velocity needed to leave the Solar System. At that point, it became part of a space exploration project that was conducted by the NASA Ames Research Center in California.

“Pioneer 10 was assembled around a hexagonal bus with a 9-foot diameter parabolic dish high-gain antenna, and the spacecraft was spin stabilized around the axis of the antenna. Its electric power was supplied by four radioisotope thermoelectric generators that provided a combined 155 watts at launch. Pioneer was launched on March 2, 1972, by an Atlas-Centaur expendable vehicle from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Between July 15, 1972, and February 15, 1973, it became the first spacecraft to traverse the asteroid belt. Photography of Jupiter began November 6, 1973, at a range of 16,000,000 miles, and about 500 images were transmitted. The closest approach to the planet was on December 4, 1973, at a range of 82,178 miles. During the mission, the on-board instruments were used to study the asteroid belt, the environment around Jupiter, the solar wind, cosmic rays, and eventually the far reaches of the Solar System and heliosphere.”

I find it hard to believe that Nasa thought that the spacecraft would last as long as it did, but I suppose that the further out it went in space, the less it would encounter the kind of space debris that came from Earth. Still, there are meteors and planets, stars that it could be pulled into, and so many more things that could have meant the destruction if the craft. Nevertheless, Pioneer 10 continued to send out radio transmissions continued between Nasa and itself until January 23, 2003, and then only because of the loss of electric power for its radio transmitter. At that point, the probe was at a distance of 12 billion kilometers (7,456,454,306.848 miles) from Earth.

According to sources, “If left undisturbed, Pioneer 10 and its sister craft Pioneer 11 will join the two Voyager spacecraft and the New Horizons spacecraft in leaving the Solar System to wander the interstellar medium. The Pioneer 10 trajectory is expected to take it in the general direction of the star Aldebaran, currently located at a distance of about 68 light years. If Aldebaran had zero relative velocity, it would require more than two million years for the spacecraft to reach it. Well before that, in about 90,000 years, Pioneer 10 will pass about 0.23 parsecs (0.75 light-years) from the late K-type star HIP 117795. This is the closest stellar flyby in the next few million years of all the four Pioneer and Voyager spacecrafts, which are leaving the Solar System.”

Shortages are usually problematic in one way or another, but sometimes they can be catastrophic, and sometimes, while not catastrophic, they can mean a really great loss. Shortages come in many forms, but when there is a shortage of something that is necessary, problems will result.

Shortages are usually problematic in one way or another, but sometimes they can be catastrophic, and sometimes, while not catastrophic, they can mean a really great loss. Shortages come in many forms, but when there is a shortage of something that is necessary, problems will result.

In the early 1980s, the world experienced a rather strange shortage…data tapes. This may seem rather benign kind of shortage. It seems like you could either just wait until more can be produced or come up with another way of recording the data. Well, that wasn’t the solution that NASA came up with. Their plan was to reuse data tapes that had outlived their usefulness. Some data tapes held data that was no longer important, and so NASA decided to use those data tapes for their temporary needs, until new data tapes could be procured.

The plan seemed like a good one and probably would have been, except that in their rush to find data tapes they could use, NASA accidentally recorded over the original Apollo 11 moon landing tapes. Unfortunately, these were the only copies of Apollo 11’s journey, and so a critical piece of human history was lost forever. In the 1990s, it was discovered that the Apollo 11 tapes were missing. This was a historical disaster, and an investigation was launched. Originally, NASA believed that the tapes were not lost forever as many claimed but stored somewhere in the Goddard Space Flight Center after the center requested that the National Archives return them in the early 1970s. It was determined the tapes had been erased and re-used during a data tape shortage during the early 1980s.

The lost footage brought about many claims of conspiracy theories, stating that man never walked on the moon at all. NASA finally released every photograph they had, but that didn’t really change people’s minds. They said it was all staged. It didn’t help matters, that the photos were very degraded. It seems like that is an ongoing

trend. Every disaster if followed by someone saying it didn’t happen. Now, I’m not saying it isn’t possible, I’m just saying that there will always be these conspiracy theories, and I just hope that at least most of our modern-day accomplishments really did happen, because the alternative would be awful. As to Apollo 11, it is just terrible that a shortage stole an important part of our history.

trend. Every disaster if followed by someone saying it didn’t happen. Now, I’m not saying it isn’t possible, I’m just saying that there will always be these conspiracy theories, and I just hope that at least most of our modern-day accomplishments really did happen, because the alternative would be awful. As to Apollo 11, it is just terrible that a shortage stole an important part of our history.

Our space program has gone through many changes over the years. There have been accidents, losses, victories, and amazing strides in both exploration and the vehicles we use to take these trips. One of the biggest goals was to have a space station so that men and women could live and work in space indefinitely…or at least for long periods of time. On June 29, 1995, the American space shuttle Atlantis docked with the Russian space station Mir. This docking formed the largest man-made satellite ever to orbit the Earth…at that time, anyway. We all know that records are meant to be broken.

Our space program has gone through many changes over the years. There have been accidents, losses, victories, and amazing strides in both exploration and the vehicles we use to take these trips. One of the biggest goals was to have a space station so that men and women could live and work in space indefinitely…or at least for long periods of time. On June 29, 1995, the American space shuttle Atlantis docked with the Russian space station Mir. This docking formed the largest man-made satellite ever to orbit the Earth…at that time, anyway. We all know that records are meant to be broken.

For a number of years, Russia and the United States had been rivals when it came to the Space Race…as well as many other things, so this joint venture was a really big deal. It was not only about the two rivals working in cooperation together, but it was also the 100th human space mission in American history. It was such a big deal, in fact, that Daniel Goldin, chief of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), called it the beginning of “a new era of friendship and cooperation” between the United States and Russia. The docking was also a big deal to people everywhere, with millions of viewers watching on television, Atlantis blasted off from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in eastern Florida on June 27, 1995.

Just after 6am on June 29, the very excited seven-member crew prepared Atlantis for docking with Mir, as both crafts orbited the Earth some 245 miles above Central Asia, near the Russian-Mongolian border. The moment they spotted the shuttle, the three cosmonauts on Mir began to broadcast Russian folk songs to Atlantis to welcome them. The party was about to begin. Over the next two hours, the shuttle’s commander, Robert “Hoot” Gibson expertly maneuvered his craft towards the space station. This was no easy task. In order to make the docking, Gibson had to steer the 100-ton shuttle to within three inches of Mir at a closing rate of no more than one foot every 10 seconds. Now, I don’t know how fast that would be in miles per hour measurement, but I think these crafts could certainly be damaged by the impact. Precision was key.

Well, the docking went perfectly that day, and by 8am it was completed, and just two seconds off the targeted arrival time, while using 200 pounds less fuel than had been anticipated. Now, that’s what I call success. When docked, Atlantis and the 123-ton Mir formed the largest spacecraft ever in orbit at that time. It was only the second time ships from two countries had linked up in space; the first was in June 1975, when an American Apollo capsule and a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft briefly joined in orbit.

Once the docking was completed, Gibson and Mir’s commander, Vladimir Dezhurov, greeted each other by clasping hands in a victorious celebration of the historic moment. A formal exchange of gifts followed, with the Atlantis crew bringing chocolate, fruit, and flowers and the Mir cosmonauts offering traditional Russian welcoming gifts of bread and salt. After the party, Atlantis remained docked with Mir for five days before returning to Earth. They left two fresh Russian cosmonauts behind on the space station and took the three veteran Mir crew members home in the shuttle. The returning crew members included two Russians and

Norman Thagard, a US astronaut who rode a Russian rocket to the space station in mid-March 1995 and spent over 100 days in space. This was a United States endurance record…at that time, anyway. This was a great alliance, especially between two former rivals. NASA’s Shuttle-Mir program continued for 11 missions and was a crucial step towards the construction of the International Space Station, which is now in orbit, and is the current largest space craft.

Norman Thagard, a US astronaut who rode a Russian rocket to the space station in mid-March 1995 and spent over 100 days in space. This was a United States endurance record…at that time, anyway. This was a great alliance, especially between two former rivals. NASA’s Shuttle-Mir program continued for 11 missions and was a crucial step towards the construction of the International Space Station, which is now in orbit, and is the current largest space craft.

Seventy-five years ago, people began seeing and having an interest in seeing Unidentified Flying Objects (UFOs). A place called Roswell, New Mexico became famous for UFO sightings, and the Air Force found itself denying any sightings. People who saw the UFOs maintained that they “know what they saw!” Roswell, New Mexico is located near the Pecos River in the southeastern part of the state. Roswell became a magnet for UFO believers due to the strange events of early July 1947, when ranch foreman W.W. Brazel found a strange, shiny material scattered over some of his land. It was like nothing he or anyone else had ever seen before.

Seventy-five years ago, people began seeing and having an interest in seeing Unidentified Flying Objects (UFOs). A place called Roswell, New Mexico became famous for UFO sightings, and the Air Force found itself denying any sightings. People who saw the UFOs maintained that they “know what they saw!” Roswell, New Mexico is located near the Pecos River in the southeastern part of the state. Roswell became a magnet for UFO believers due to the strange events of early July 1947, when ranch foreman W.W. Brazel found a strange, shiny material scattered over some of his land. It was like nothing he or anyone else had ever seen before.

I’m not one to believe in UFOs, but I must admit that these were unusual sightings. Public interest in Unidentified Flying Objects, or UFOs, began to flourish in the 1940s, when developments in space travel and the dawn of the atomic age caused many Americans to turn their attention to the skies. Brazel turned the material over to the sheriff, who passed it on to authorities at the nearby Air Force base. Not unexpectedly, the Air Force officials announced they had recovered the wreckage of a “flying disk.” A local newspaper put the story on its front page, launching Roswell into the spotlight of the public’s UFO fascination. I’m sure the newspaper was beyond excited to get the story, because a good story is great for selling newspapers…especially when it is unbelievable.

Of course, in typical government style, the Air Force took back their story, saying the debris had been merely a downed weather balloon. After that, the general public lost interest in the UFO, except for the die-hard UFO believers, nicknamed “ufologists.” With that, the “Roswell Incident” faded into oblivion…until the late 1970s. Then, claims surfaced that the military had invented the weather balloon story as a cover-up. Of course, these would be considered the conspiracy theorists of their day. Believers in this theory insisted that officials had retrieved several alien bodies from the crashed spacecraft, which were now stored in the mysterious Area 51 installation in Nevada. Now, the Air Force had clean-up to do. Seeking to dispel these suspicions, the Air Force issued a 1,000-page report in 1994 stating that “the crashed object was actually a high-altitude weather balloon launched from a nearby missile test-site as part of a classified experiment aimed at monitoring the atmosphere in order to detect Soviet nuclear tests.” Then on June 24, 1997, US Air Force officials release a 231-page report dismissing long-standing claims of an alien spacecraft crash in Roswell, New Mexico, almost exactly 50 years earlier.

Many people have heard this story, of course, and Area 51 remains a mystery to many people to this day. Most think that the whole thing was a hoax or a weather balloon, but now…suddenly, NASA has decided to take up the study of UFOs…seriously!! See, that, to me, seems more like a conspiracy theory or at the very least a way to take our minds off of other events going on in our world today, than it is a legitimate search for UFOs or

anything else. According to a story by The Sun, on May 27, 2022, “NASA has reportedly confirmed it will officially join the hunt for UFOs after a groundbreaking UAP Congress hearing earlier this month. Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAPs) and official sightings were recently discussed at a public US Congress hearing on May 17. Nasa had previously said it “does not actively search for” or research UAPs.” What a way to spend our money…and why now, after all these years.

anything else. According to a story by The Sun, on May 27, 2022, “NASA has reportedly confirmed it will officially join the hunt for UFOs after a groundbreaking UAP Congress hearing earlier this month. Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAPs) and official sightings were recently discussed at a public US Congress hearing on May 17. Nasa had previously said it “does not actively search for” or research UAPs.” What a way to spend our money…and why now, after all these years.

The race to space was not without the unfortunate casualties here and there. Nevertheless, as a whole, it has been a very safe program. The first deaths experienced by the United States, in the NASA program were those of Command Pilot Gus Grissom, Senior Pilot Ed White, and Pilot Roger Chaffee on January 27, 1967, when he Command Module interior caught fire and burned, during a pre-launch test on Launch Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy. At that time there was no interior latch, so the men could not escape the burning module. It was a terrible tragedy for the NASA program and the nation as a whole. The United States had been involved in a “race to space” with the Soviet Union, and the fire was a terrible setback…not to mention the horrific loss of life.

The race to space was not without the unfortunate casualties here and there. Nevertheless, as a whole, it has been a very safe program. The first deaths experienced by the United States, in the NASA program were those of Command Pilot Gus Grissom, Senior Pilot Ed White, and Pilot Roger Chaffee on January 27, 1967, when he Command Module interior caught fire and burned, during a pre-launch test on Launch Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy. At that time there was no interior latch, so the men could not escape the burning module. It was a terrible tragedy for the NASA program and the nation as a whole. The United States had been involved in a “race to space” with the Soviet Union, and the fire was a terrible setback…not to mention the horrific loss of life.

On April 24, 1967, just a few short months later, the Soviet Union also experienced a tragic set back, when Soviet Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov is killed when his parachute failed to deploy during his spacecraft’s landing. Komarov, a fighter pilot and aeronautical engineer, was testing the spacecraft Soyuz I at the time of the catastrophic failure of the parachute. He had made his first space trip in 1964, three years before the doomed 1967 voyage. After 24 hours and 16 orbits of the earth in Soyuz I, Komarov was scheduled to reenter the atmosphere, but ran into difficulty handling the vessel and was unable to fire the rocket brakes. It took two more trips around the earth before the cosmonaut could manage reentry. When Soyuz I reached an altitude of 23,000 feet, a parachute was supposed to deploy, bringing Komarov safely to earth. Unfortunately, the maneuvering problems he had caused the lines of the chute had gotten tangled and there was no backup chute. When Soyuz I reached an altitude of 23,000 feet, a parachute was supposed to deploy, bringing Komarov safely to earth. Komarov plunged to the ground and was killed.

Things in the Soviet Union were different than in the United States, and Komarov’s wife had not been told of the Soyuz I launch until after Komarov was already in orbit. Sadly, she did not get to say goodbye to her husband. Komarov was considered a national hero, and there was vast public mourning in Moscow. Komarov’s

ashes were buried in the wall of the Kremlin. Space flight is dangerous, a fact that is well known to all who venture into its corridors. Despite the dangers, both the Soviet Union and the United States continued their space exploration. The United States landed men on the moon just two years later. Everyone was determined to see the program through, as they continue to be to this day.

ashes were buried in the wall of the Kremlin. Space flight is dangerous, a fact that is well known to all who venture into its corridors. Despite the dangers, both the Soviet Union and the United States continued their space exploration. The United States landed men on the moon just two years later. Everyone was determined to see the program through, as they continue to be to this day.