militia

For most women, especially during the Revolutionary War era, life’s losses brought a long time of mourning, the wearing of black dresses, and times of reflection, before they eventually consider remarrying. For Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey, whose lifestyle earned her the name “Mad Anne” for her acts of bravery and heroism that were considered to be somewhat eccentric for a woman of her time, loss brought about quite the opposite reaction. Anne Hennis was born in Liverpool England in 1742. She was formally educated and learned to read and write. Her first experience with loss came before she turned 18. It is not known how they died, but both of Anne’s parents were gone before she turned 18, and she became an orphan. Life for Ann, who was poor and had a hard time earning enough money to survive, immediately became very hard. Anne had family near Staunton in the Shenandoah Valley, and when she was 19, she sailed to America to live with them. There, in 1765, she met and married Richard Trotter, a seasoned frontiersman and experienced soldier. The couple had one son named William.

For most women, especially during the Revolutionary War era, life’s losses brought a long time of mourning, the wearing of black dresses, and times of reflection, before they eventually consider remarrying. For Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey, whose lifestyle earned her the name “Mad Anne” for her acts of bravery and heroism that were considered to be somewhat eccentric for a woman of her time, loss brought about quite the opposite reaction. Anne Hennis was born in Liverpool England in 1742. She was formally educated and learned to read and write. Her first experience with loss came before she turned 18. It is not known how they died, but both of Anne’s parents were gone before she turned 18, and she became an orphan. Life for Ann, who was poor and had a hard time earning enough money to survive, immediately became very hard. Anne had family near Staunton in the Shenandoah Valley, and when she was 19, she sailed to America to live with them. There, in 1765, she met and married Richard Trotter, a seasoned frontiersman and experienced soldier. The couple had one son named William.

During the westward movement, when more and more people were heading west in search of land and adventure, fights began to break out between settlers and the Indians who had lived there for many years. The Governor of Virginia organized border militia to protect the settlers there. Richard Trotter joined this militia. On October 19, 1774, Shawnee Chief Cornstalk attacked the Virginia militia, hoping to halt their advance into the Ohio Country. This became known as the Battle of Point Pleasant. The battle raged on until Cornstalk finally retreated. The Virginians, along with a second force led by Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, then marched into the Ohio Country. Cornstalk had no choice but to agree to a treaty, ending the war. Many men on both sides lost their lives in the battle, including Richard Trotter.

For Anne this could have meant years of sadness as a widow, but Anne would have none of that. Anne, upon learning of her husband’s death, and determined to seek revenge, left her young son in the care of neighbors, dressed in the clothing of a frontiersman, and set out to avenge her loss. A woman alone going out to kill the Indians seemed like an insane move to make, and most people probably thought she would be dead in a matter of days…but they didn’t know Anne. She became known as “Mad Anne” from that time forward….to whites and Indians alike. In the beginning, Anne rode from one recruiting station to another, asking them to volunteer their services to the militia in order to keep the women and children of the border safe, to fight for freedom from the Indians, and later the British.

People from Staunton, Virginia, to what is now Charleston, West Virginia, and Gallipolis, Ohio, knew Anne, mostly due to the unusual sight she presented. She usually wore buckskin leggings, petticoats, heavy brogan shoes, a man’s coat and hat, a hunting knife in a belt around her waist, and a rifle slung over her shoulder…everything she needed to be in the pioneer spirit in the late 1700s. Although Mad Anne mostly rode up and down the western frontier, she also recruited for the Continental Army, and delivered messages between various Army detachments during the Revolutionary War. It seemed that there was no job she wouldn’t take, including traveling as a courier on horseback between Forts Savannah and Randolph, a distance of almost 160 miles. Her fearless personality made her well known and respected by the settlers along the route. Mad Anne  was even respected, or maybe feared is a better word, by the Shawnee Indians. On her rides Bailey often came across a particular group of Shawnee Indians. They often chased her, then on one such encounter, she had had enough. Just when she was about to be caught, she jumped off her horse and hid in a log. Strangely, the Shawnee looked everywhere for her and even stopped to rest on the log, but they could not find her. Finally, they gave up and stole her horse. She waited a while after they left, and then came out of the log. She waited until nightfall, then crept into their camp and retrieved her horse…a bold move, but nothing like the next move she made. Once she was far enough away, she started screaming and shrieking at the top of her lungs. Now waking up to that would be shocking enough, but this woman was acting totally crazy, and the Shawnee thought she was possessed and therefore could not be injured by a bullet or arrow. After that display, the Shawnee saw her often, but the kept far away from her, because they were totally afraid of her. With that assurance backing her, Mad Anne knew that she was relatively safe living in the woods.

was even respected, or maybe feared is a better word, by the Shawnee Indians. On her rides Bailey often came across a particular group of Shawnee Indians. They often chased her, then on one such encounter, she had had enough. Just when she was about to be caught, she jumped off her horse and hid in a log. Strangely, the Shawnee looked everywhere for her and even stopped to rest on the log, but they could not find her. Finally, they gave up and stole her horse. She waited a while after they left, and then came out of the log. She waited until nightfall, then crept into their camp and retrieved her horse…a bold move, but nothing like the next move she made. Once she was far enough away, she started screaming and shrieking at the top of her lungs. Now waking up to that would be shocking enough, but this woman was acting totally crazy, and the Shawnee thought she was possessed and therefore could not be injured by a bullet or arrow. After that display, the Shawnee saw her often, but the kept far away from her, because they were totally afraid of her. With that assurance backing her, Mad Anne knew that she was relatively safe living in the woods.

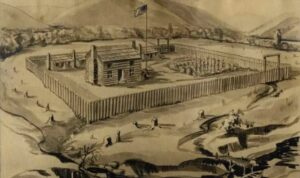

Anne met John Bailey, a member of a legendary group of frontier scouts called the Rangers, after several years living on her own. The Rangers were defending the Roanoke and Catawba settlements from Indian attacks. He was rather smitten with Mad Anne’s rough ways, and they were married November 3, 1785. In 1787, along the Kanawha River at the mouth of the Elk River, a blockhouse was built. The block house would later become Fort Lee in honor of Virginia’s Governor Henry Lee. Fort Lee was where John Bailey was assigned to duty, taking with him his now famous, gun-toting, hard-riding bride.

In 1788, John Bailey was transferred to Fort Clendenin, which was a more active area of conflict between the settlers and Native Americans. Anne Bailey began working for the settlers as well, riding on horseback to warn them of impending attacks. In 1791, she singlehandedly saved Fort Lee from certain destruction by hostile Indians with a three-day, 200–mile round trip to replenish their supply of gunpowder. She rode for hours, finally reaching Fort Savannah at Lewisburg, where the gunpowder was quickly packed aboard her horse and one additional mount, before she reversed her direction and galloped full speed back to Fort Lee.

After she returned, the siege was ended, the attackers were defeated. For her bravery Anne was given the horse that had carried her away and brought her safely back. The animal was said to have been a beautiful black, sporting white feet and a blazed face. She dubbed him Liverpool, in honor of her birthplace. Anne Bailey was forty-nine years old when she made this famous ride. Anne became a legend among the other settlers, and she was always welcome in their homes. John Bailey died in 1802, and Anne decided that she no longer wanted to live in a house, so she lived in the wilderness for over 20 years. She visited friends in town occasionally, but usually slept outside. Her favorite place was a cave near Thirteen Mile Creek.

A widow for the second time, and in her late fifties, Anne later went to live with her son, but her love for riding and of the wilderness had not ceased. For many years afterwards she could be seen riding from Point Pleasant to Lewisburg and Staunton, carrying mail and as an express messenger. Bailey continued working as a messenger,  bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. She finally retired in 1817 after making one last trip to Charleston at age 75. In 1818 Anne moved with her son and his family to his new farm in Gallia County, Ohio. Instead of asking her to stay with his family, her son, who had apparently never felt any ill-will toward his mother who was often not around, built her a cabin nearby so she would still feel independent. Bailey continued working as a messenger, bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey died at Gallipolis, Ohio, November 22, 1825, at the age of 83. She was buried in the Trotter Graveyard near her son’s home, and her remains rested there for seventy-six years. On October 10, 1901, her remains were re-interred in Monument Park in Point Pleasant, under the auspices of the Colonel Charles Lewis, Jr. Chapter of the D. A. R.

bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. She finally retired in 1817 after making one last trip to Charleston at age 75. In 1818 Anne moved with her son and his family to his new farm in Gallia County, Ohio. Instead of asking her to stay with his family, her son, who had apparently never felt any ill-will toward his mother who was often not around, built her a cabin nearby so she would still feel independent. Bailey continued working as a messenger, bringing supplies for the settlers throughout the area. Anne Hennis Trotter Bailey died at Gallipolis, Ohio, November 22, 1825, at the age of 83. She was buried in the Trotter Graveyard near her son’s home, and her remains rested there for seventy-six years. On October 10, 1901, her remains were re-interred in Monument Park in Point Pleasant, under the auspices of the Colonel Charles Lewis, Jr. Chapter of the D. A. R.

I grew up in a time when western shows were all the rage on television. One show that my family always watched was Daniel Boone. Most people know Daniel Boone from their history classes, as an American frontiersman. Most of his fame stemmed from his exploits during the exploration and settlement of Kentucky. Boone arrived in Kentucky in 1767, about 25 years before it became a state on June 1, 1792. He spent the next 30 years exploring and settling the lands of Kentucky, including carving out the Wilderness Road and building the settlement station of Boonesboro. Without Boone the history of Kentucky would have been much different.

I grew up in a time when western shows were all the rage on television. One show that my family always watched was Daniel Boone. Most people know Daniel Boone from their history classes, as an American frontiersman. Most of his fame stemmed from his exploits during the exploration and settlement of Kentucky. Boone arrived in Kentucky in 1767, about 25 years before it became a state on June 1, 1792. He spent the next 30 years exploring and settling the lands of Kentucky, including carving out the Wilderness Road and building the settlement station of Boonesboro. Without Boone the history of Kentucky would have been much different.

Boone was born near Reading, in Berks County, Pennsylvania, the son of hard-working but adventurous Quaker parents. He learned some blacksmithing, but had very little formal education. Daniel appears to have been a scrappy lad who loved hunting, the wilderness, and independence. When his parents left Pennsylvania in 1750 bound for the Yadkin valley of northwest North Carolina, Daniel went along willingly, because the move fit right in with his spirit of adventure.

Upon arriving in North Carolina, the cutting edge of the frontier, he was able to indulge his hunting prowess and love of the wilderness. In the years that followed, he served as a wagoner with General Edward Braddock’s ill-fated expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755. Boone then married a neighbor’s daughter, Rebecca Bryan, in 1756, and in 1758 is believed to have been a wagoner with General John Forbes who was hacking out the road to Fort Duquesne, which he rebuilt as Fort Pitt…now Pittsburgh. Back in North Carolina, Daniel purchased land from his father but never seriously engaged in farming. He loved to roam far too much to settle down and farm the land in one place. In 1763 he and his brother Squire journeyed to Florida, but for unknown reasons they did not stay. I guess Kentucky would always be his first love.

Boone was first in eastern Kentucky in 1767, but his expedition of 1769-1771 is more widely known. With a small party Boone advanced along the Warrior’s Path into a beautiful garden-like region. When the time came for the party to return he remained behind in the wilderness until March 1771. On the way home, he and his brother were robbed by Indians of their deer skins and pelts, but the two remained exuberant over the land known as “Kentuck.”

So much did Daniel love that “dark and bloody ground” that he tried to return in 1773, taking forty settlers with him, but the Indians drove them back. The next year he went again into the region carrying a warning of Indian troubles to Governor John Murray Dunmore’s surveyors. As Judge Richard Henderson was concluding the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals. in March 1775, by which much of Kentucky was sold to his Transylvania Company, Boone was hacking out the Wilderness Road. As soon as he reached his destination, he began building Boonesboro, one of several stations, or forts under construction at that time. For the next four years…through 1778…Boone was a captain in the militia, and was busy defending the settlements. His leadership  helped save the three remaining Kentucky stations, Boonesboro, Logan’s (St. Asaph’s), and Harrodsburg. These were years of many ambushes; such as Blue Licks in 1778; captures, including Boone, himself, who was was captured but escaped from the Shawnees; rescues, and desperate defenses.

helped save the three remaining Kentucky stations, Boonesboro, Logan’s (St. Asaph’s), and Harrodsburg. These were years of many ambushes; such as Blue Licks in 1778; captures, including Boone, himself, who was was captured but escaped from the Shawnees; rescues, and desperate defenses.

I knew and have learned much about Daniel Boone over the years, but for me the most interesting thing I have learned is that Daniel Boone is my 5th Cousin 8 times removed, on the Pattan side of my mother, Collene Spencer’s family. It is a small, small world. Today is Daniel Boone Day. It is a day to remember all this great man did for our country.

As with any war, there are opinions that are polar opposites from each other. After all, if they all agreed, there would be no need for war. The Revolutionary War was no different. Yes, the British wanted to keep the United States as colonies belonging to the crown, but the people of the United States would have none of it…well, most of the people anyway. It seems shocking to us now, to think that there would be people in the United States who would want us to remain under Britain’s rule, but in fact, there were. They were known as the Loyalists, and they set about doing whatever they could to cause the United States to lose the Revolutionary War.

As with any war, there are opinions that are polar opposites from each other. After all, if they all agreed, there would be no need for war. The Revolutionary War was no different. Yes, the British wanted to keep the United States as colonies belonging to the crown, but the people of the United States would have none of it…well, most of the people anyway. It seems shocking to us now, to think that there would be people in the United States who would want us to remain under Britain’s rule, but in fact, there were. They were known as the Loyalists, and they set about doing whatever they could to cause the United States to lose the Revolutionary War.

Patriot, Lieutenant Colonel Francis “The Swamp Fox” Marion was fresh from a victory at Nelson’s Ferry on the Santee River in South Carolina on August 20, 1780. Marion, who was just five feet tall, won fame and the “Swamp Fox” nickname for his ability to strike and then quickly retreat into the South Carolina swamps without a trace. Marion used irregular methods of warfare and is considered  one of the fathers of modern guerrilla warfare and maneuver warfare, and is credited in the lineage of the United States Army Rangers. After the victory at Nelson’s Ferry, Marion and 52 of his militiamen rode east in order to escape the pursuing British Loyalists. They were successful, but during their escape, a second and much larger, force of Loyalists led by Major Micajah Ganey, attacked the militia from the northeast. Marion’s advance guard, led by Major John James, defeated Ganey’s advance guard and Marion ambushed the rest, causing Ganey’s main body of 200 Loyalists to flee in panic. The success of Marion’s militia broke the Loyalist stronghold on South Carolina east of the PeeDee River and attracted another 60 volunteers to the Patriot cause.

one of the fathers of modern guerrilla warfare and maneuver warfare, and is credited in the lineage of the United States Army Rangers. After the victory at Nelson’s Ferry, Marion and 52 of his militiamen rode east in order to escape the pursuing British Loyalists. They were successful, but during their escape, a second and much larger, force of Loyalists led by Major Micajah Ganey, attacked the militia from the northeast. Marion’s advance guard, led by Major John James, defeated Ganey’s advance guard and Marion ambushed the rest, causing Ganey’s main body of 200 Loyalists to flee in panic. The success of Marion’s militia broke the Loyalist stronghold on South Carolina east of the PeeDee River and attracted another 60 volunteers to the Patriot cause.

Marion rarely committed his men to frontal warfare, which was much more risky, but repeatedly surprised larger bodies of Loyalists or British regulars with quick surprise attacks and equally quick withdrawal from the  field. He was considered almost a ghost. Marion had previously earned fame as the only senior Continental officer in the area to escape the British following the fall of Charleston on May 12, 1780. His military strategy, while odd for the time, was really advanced for the time, and similar to some of today’s strategies. Marion took over the South Carolina militia force, first assembled by Thomas Sumter in 1780. Sumter returned home to bring Carolina Loyalists’ style terror tactics on the Loyalists who burned his plantation. After being wounded, Sumter withdrew from active fighting. Marion replaced him and teamed up with Major General Nathaniel Greene, who arrived in the Carolinas to lead the Continental forces in October 1780. Together, they are credited with pulling a Patriot victory from the jaws of defeat in the southern states.

field. He was considered almost a ghost. Marion had previously earned fame as the only senior Continental officer in the area to escape the British following the fall of Charleston on May 12, 1780. His military strategy, while odd for the time, was really advanced for the time, and similar to some of today’s strategies. Marion took over the South Carolina militia force, first assembled by Thomas Sumter in 1780. Sumter returned home to bring Carolina Loyalists’ style terror tactics on the Loyalists who burned his plantation. After being wounded, Sumter withdrew from active fighting. Marion replaced him and teamed up with Major General Nathaniel Greene, who arrived in the Carolinas to lead the Continental forces in October 1780. Together, they are credited with pulling a Patriot victory from the jaws of defeat in the southern states.

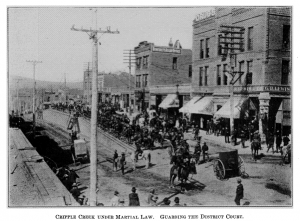

I think a lot of people know or at least have heard of Cripple Creek, Colorado. Most people think of the fourteen casinos located there, and I suppose that casinos are a fitting thing for Cripple Creek to be known for, but it wasn’t always that way. Cripple Creek became a gold mining boom town in 1894 after gold was discovered there. At that time 150 gold mines suddenly sprang up, and with them, a strong miners union…the Free Coinage Union Number 19, which was a part of the militant Western Federation of Miners.

I think a lot of people know or at least have heard of Cripple Creek, Colorado. Most people think of the fourteen casinos located there, and I suppose that casinos are a fitting thing for Cripple Creek to be known for, but it wasn’t always that way. Cripple Creek became a gold mining boom town in 1894 after gold was discovered there. At that time 150 gold mines suddenly sprang up, and with them, a strong miners union…the Free Coinage Union Number 19, which was a part of the militant Western Federation of Miners.

As with any gold mining operation, desparate workers began pouring in from all over the country. Before long Cripple Creek had a huge labor surplus. With the labor surplus, the owners begin requiring extra hours, with no pay increase, or the alternative, they could keep the current 8 hours a day with a pay reduction of 50 cents. The Western Federation of Miners opposed both plans, and the miners when on strike. Their picket lines and refusal to work closed most of the mines. They showed what solidarity is all about. The miners who were still going down in the  working mines assessed themselves 10 percent of their wages to support the strikers, and the union set up soup kitchens. How often to you see people who can’t afford to strike, but who are willing to support those who do strike.

working mines assessed themselves 10 percent of their wages to support the strikers, and the union set up soup kitchens. How often to you see people who can’t afford to strike, but who are willing to support those who do strike.

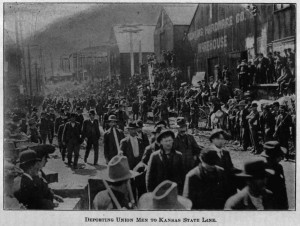

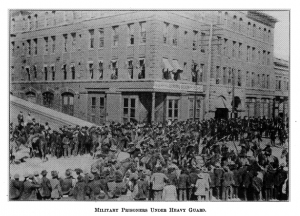

The governer of Colorado, David Waite would not help the labor bosses, but they had the county Sheriff, Frank Bowers in their pocket. They told the miners to go back to work, they would not. By the end of October, things had gotten so out of hand that finally, on November 23, 1903, Governor Peabody agreed to send the state miltia to protect replacement workers that the bosses had brought in. The striking miners were furious and they barricaded the roads and railways. The soldiers began rounding up the union members and their sympathizers, including the entire staff of a pro-union newspaper, and imprisoned them without charges or any evidence that they had done anything wrong.

The miners and others who were imprisoned complained that their constitutional rights had been violated, and

one anti-union judge replied, “To hell with the Constitution; we’re not following the Constitution!” Those tactics brought out the more radical elements of the Western Federation of Miners, and in June of 1904 Harry Orchard, who was a professional terrorist the the union employed, blew up a railroad station, whick killed 13 strikebreakers. With the bombing came the outrage of the public and the deportation of the Western Federation of Miners leaders. By midsummer, the strike was over and the Western Federation of Miners never regained the same level of power it had originally had in the Colorado mining districts. Even in this day and age, the unions and the bosses seem to always be at odds, and I suppose that something like this could happen again.