medal of honor

What makes a Medal of Honor winner? I don’t mean what act actually earns them the medal, but rather what causes them to get to that point and beyond. The Medal of Honor is the United States government’s highest and most prestigious military decoration that may be awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, Space Force guardians, and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor…or great courage in the face of danger, especially in battle. I seriously doubt if the winner gave any thought to what he had to do to win the medal…there is just no time, and people don’t perform heroic acts just for the medal. It’s bigger than that.

What makes a Medal of Honor winner? I don’t mean what act actually earns them the medal, but rather what causes them to get to that point and beyond. The Medal of Honor is the United States government’s highest and most prestigious military decoration that may be awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, Space Force guardians, and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor…or great courage in the face of danger, especially in battle. I seriously doubt if the winner gave any thought to what he had to do to win the medal…there is just no time, and people don’t perform heroic acts just for the medal. It’s bigger than that.

One man, Corporal Ronald Rosser, earned his Medal of Honor while serving in the 38th Regiment of the 2nd Infantry Division during the Korean War. Rosser enlisted in Army at the age of 17 and served from 1946 until 1949. His tour was finished, and he went home, but then his younger brother was killed in Korea in February of 1951. Rosser was devastated, but instead of wallowing in grief, he chose to honor his brother. Rosser re-enlisted to “finish his [brother’s] tour” of duty. Revenge was the only thing he could do for his brother now, and Rosser wanted revenge. In January of 1952, Rosser was a part of the regiment’s L Company. L Company was dispatched to capture an enemy-occupied hill. The battle there was fierce and enemy resistance caused heavy casualties. L Company was reduced to just 35 men from the initial 170 sent out, but they were ordered to make one more  attempt to take the hill. Orders are orders, and as I said, the men didn’t really have time to think about how they could prove their courage. Rosser rallied the remaining men and charged the hill. Enemy fire continued to be heavy, but Rosser attacked the enemy position three times, killing 13 enemy soldiers, and although wounded himself, carried several men to safety. It truly was a courageous act, and one worthy of the Medal of Honor, but not one that Rosser had planned in any way. He just knew that he needed to save as many lives as he could, because he couldn’t live with himself if he didn’t. On June 27, 1952, Rosser was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman at the White House for his heroism. On September 20, 1966, another of Rosser’s brothers, PFC Gary Edward Rosser, USMC, was killed in action, this time in the Vietnam War. Rosser requested a combat assignment in Vietnam but was rejected and subsequently retired from the army soon after. Rosser married Sandra Kay (nee Smith) Rosser who died November 28, 2014. He was the father of Pamela (nee Rosser) Lovell. Rosser died on August 26, 2020, in Bumpus Mills, Tennessee at the age of 90.

attempt to take the hill. Orders are orders, and as I said, the men didn’t really have time to think about how they could prove their courage. Rosser rallied the remaining men and charged the hill. Enemy fire continued to be heavy, but Rosser attacked the enemy position three times, killing 13 enemy soldiers, and although wounded himself, carried several men to safety. It truly was a courageous act, and one worthy of the Medal of Honor, but not one that Rosser had planned in any way. He just knew that he needed to save as many lives as he could, because he couldn’t live with himself if he didn’t. On June 27, 1952, Rosser was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman at the White House for his heroism. On September 20, 1966, another of Rosser’s brothers, PFC Gary Edward Rosser, USMC, was killed in action, this time in the Vietnam War. Rosser requested a combat assignment in Vietnam but was rejected and subsequently retired from the army soon after. Rosser married Sandra Kay (nee Smith) Rosser who died November 28, 2014. He was the father of Pamela (nee Rosser) Lovell. Rosser died on August 26, 2020, in Bumpus Mills, Tennessee at the age of 90.

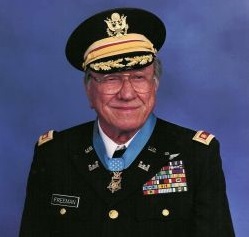

Ed Freeman first served in the military during World War II, in the United States Navy on the USS Cacapon (AO-52). While World War II was in no way uneventful or unimportant, it was not the most eventful part of Freeman’s service. Freeman decided to continue on in the military. Freeman had reached the rank of first sergeant by the time the Korean War began. By this time Freeman was in the Corps of Engineers, but his company fought as infantry soldiers in Korea. Freeman found himself fighting in the Battle of Pork Chop Hill, where he earned a battlefield commission as one of only 14 survivors out of 257 men who made it through the opening stages of the battle. His second lieutenant bars were pinned on by General James Van Fleet personally. He was given command of B Company and led them back up Pork Chop Hill.

Ed Freeman first served in the military during World War II, in the United States Navy on the USS Cacapon (AO-52). While World War II was in no way uneventful or unimportant, it was not the most eventful part of Freeman’s service. Freeman decided to continue on in the military. Freeman had reached the rank of first sergeant by the time the Korean War began. By this time Freeman was in the Corps of Engineers, but his company fought as infantry soldiers in Korea. Freeman found himself fighting in the Battle of Pork Chop Hill, where he earned a battlefield commission as one of only 14 survivors out of 257 men who made it through the opening stages of the battle. His second lieutenant bars were pinned on by General James Van Fleet personally. He was given command of B Company and led them back up Pork Chop Hill.

It was Freeman’s childhood dream to become a pilot, and his new commission made him eligible to become a pilot. Nevertheless, there was one drawback. When he applied for pilot training he was told that, at six feet four inches, he was “too tall” for pilot duty. That phrase stuck, and he became known as “Too Tall” for the rest of his career. It was a devastating setback, but in 1955, the height limit for pilots was raised and Freeman was finally accepted into flight school. He first flew fixed-wing army airplanes, but later switched to helicopters. When the Korean War ended, he flew the world on mapping missions.

By this time, Ed W. “Too Tall” Freeman had already had many success stories, but his real success story came during the Vietnam War, during the Battle of Ia Drang, specifically on November 14, 1965. During the battle, there were multiple men injured and the possibility of them dying was very real. Their unit was outnumbered 8-1 and the enemy fire on the men on the ground was so intense from 100 yards away, that the Commanding Officer ordered the MedEvac helicopters to stop coming in. That was basically a death sentence for the wounded men. The men were at LZ X-Ray, one of the most legendary war sites in Vietnam. It was here that the United States had its first major battle with the North Vietnamese People’s Army of Vietnam, the first very violent round of a bout that would last ten more years. There was really no way for the MedEvac helicopters to save them. Enter, Captain Ed Freeman, who was not a MedEvac pilot, by the way. Nevertheless, that did not stop him. He could not leave a man behind, much less 29 men. That this was not his job, meant nothing to Freeman, who heard the radio call and decided he was going to fly his Huey down into the machine gun fire anyway. He had not been given orders not to go, because he was not a MedEvac pilot, so he went. Those men soon knew that Captain Ed Freeman was coming in for them. Freeman dropped his Huey in and sat there in the machine gun fire, as they loaded 3 men at a time on board. Then, he flew up and out through the gunfire to get these men to the medical teams safety. And, he didn’t go in just once!! He kept going back…13 more times!! He went in until all the wounded were out. No one knew until the mission was over that the Captain had been hit 4 times in the legs and left arm.

Ed “Too Tall” Freeman was born on November 20, 1927 in Neely, Mississippi, the sixth of nine children. At the age of 13, he saw thousands of men on maneuvers pass by his home in Mississippi. He knew then that he wanted to become a soldier. Freeman grew up in nearby McLain, Mississippi, and graduated from Washington High School, however, at age 17, before graduating from high school, Freeman served in the United States Navy for two years. He then returned to his hometown and graduated from high school after the war. He joined the United States Army in September 1948, and married Barbara Morgan on April 30, 1955. They had two sons. Mike was born in 1956, and Doug was born in 1962.

Freeman’s commanding officer nominated him for the Medal of Honor for his actions at Ia Drang on November 14, 1965. Unfortunately, not in time to meet a two-year deadline in place at that time. He was instead awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The Medal of Honor nomination was disregarded until 1995, when the two-year

deadline was removed. He was finally and formally presented with the medal on July 16, 2001, in the East Room of the White House by President George W. Bush. Freeman died on August 20, 2008, due to complications from Parkinson’s disease. He was buried with full military honors at the Idaho State Veterans Cemetery in Boise.

deadline was removed. He was finally and formally presented with the medal on July 16, 2001, in the East Room of the White House by President George W. Bush. Freeman died on August 20, 2008, due to complications from Parkinson’s disease. He was buried with full military honors at the Idaho State Veterans Cemetery in Boise.

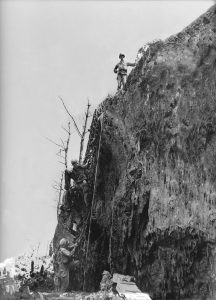

As with any war, there are a number of people who, because of their religious or personal beliefs, cannot bring themselves to participate in the taking of another life. That leaves war off the table for them. Desmond Doss, born February 7, 1919, was a United States Army corporal who served as a combat medic in the infantry during World War II. That’s what happened to the conscientious objectors. They didn’t just get to go home, they stayed in as a medic, without a gun, who was known as “Preacher” to those around him. Doss may not have had a gun, but he managed to be awarded the Bronze Star Medal with a “V” device, for exceptional valor in aiding wounded soldiers under fire in Guam and the Philippines. Doss went on to distinguish himself in the Battle of Okinawa, saved the lives of 50–100 wounded infantrymen atop the area known by the 96th Division as the Maeda Escarpment or Hacksaw Ridge. With that action, Doss became the only conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor.

As with any war, there are a number of people who, because of their religious or personal beliefs, cannot bring themselves to participate in the taking of another life. That leaves war off the table for them. Desmond Doss, born February 7, 1919, was a United States Army corporal who served as a combat medic in the infantry during World War II. That’s what happened to the conscientious objectors. They didn’t just get to go home, they stayed in as a medic, without a gun, who was known as “Preacher” to those around him. Doss may not have had a gun, but he managed to be awarded the Bronze Star Medal with a “V” device, for exceptional valor in aiding wounded soldiers under fire in Guam and the Philippines. Doss went on to distinguish himself in the Battle of Okinawa, saved the lives of 50–100 wounded infantrymen atop the area known by the 96th Division as the Maeda Escarpment or Hacksaw Ridge. With that action, Doss became the only conscientious objector to receive the Medal of Honor.

Before World War II began, Doss worked as a joiner in a shipyard in Newport News, Virginia. While he didn’t feel like he could kill people, Doss did want to serve his country. So, despite being  offered a deferment because he worked in the shipyards, Doss joined the Army on April 1, 1942 at Camp Lee, Virginia. Doss was sent to Fort Jackson in South Carolina for training with the reactivated 77th Infantry Division. His brother, Harold Doss, served aboard the USS Lindsey. Still, Doss refused to kill an enemy soldier or carry a weapon into combat because of his personal beliefs as a Seventh-day Adventist. He consequently became a medic assigned to the 2nd Platoon, Company B, 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, 77th Infantry Division. While he did not carry a weapon, Doss was wounded four times in Okinawa, because he put himself in harms way to help his fellow soldiers. He was evacuated on May 21, 1945, aboard the USS Mercy. Doss suffered a left arm fracture from a sniper’s bullet and at one point had seventeen pieces of shrapnel embedded in his body.

offered a deferment because he worked in the shipyards, Doss joined the Army on April 1, 1942 at Camp Lee, Virginia. Doss was sent to Fort Jackson in South Carolina for training with the reactivated 77th Infantry Division. His brother, Harold Doss, served aboard the USS Lindsey. Still, Doss refused to kill an enemy soldier or carry a weapon into combat because of his personal beliefs as a Seventh-day Adventist. He consequently became a medic assigned to the 2nd Platoon, Company B, 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, 77th Infantry Division. While he did not carry a weapon, Doss was wounded four times in Okinawa, because he put himself in harms way to help his fellow soldiers. He was evacuated on May 21, 1945, aboard the USS Mercy. Doss suffered a left arm fracture from a sniper’s bullet and at one point had seventeen pieces of shrapnel embedded in his body.

After the war, Doss went home to continue his career in carpentry. Unfortunately, extensive damage to his left  arm made carpentry a thing of his past. In 1946, Doss was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which he had contracted on Leyte. He underwent treatment for five and a half years, losing a lung and five ribs before being discharged from the hospital in August 1951 with 90% disability. He continued to receive treatment from the military. Then, an overdose of antibiotics rendered him completely deaf in 1976, after which he was given 100% disability. He received a cochlear implant in 1988, and was able to finally hear again. Despite the severity of his injuries, Doss managed to raise a family on a small farm in Rising Fawn, Georgia. He married Dorothy Pauline Schutte on August 17, 1942, and they had one child, Desmond “Tommy” Doss Jr, born in 1946. Dorothy died on November 17, 1991 in a car accident, in which Desmond was driving and lost control of the vehicle. It was a devastating loss. Doss remarried on July 1, 1993, to Frances May Duman. In March of 2006, he was hospitalized for difficulty breathing. Doss died on March 23, 2006, at his home in Piedmont, Alabama.

arm made carpentry a thing of his past. In 1946, Doss was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which he had contracted on Leyte. He underwent treatment for five and a half years, losing a lung and five ribs before being discharged from the hospital in August 1951 with 90% disability. He continued to receive treatment from the military. Then, an overdose of antibiotics rendered him completely deaf in 1976, after which he was given 100% disability. He received a cochlear implant in 1988, and was able to finally hear again. Despite the severity of his injuries, Doss managed to raise a family on a small farm in Rising Fawn, Georgia. He married Dorothy Pauline Schutte on August 17, 1942, and they had one child, Desmond “Tommy” Doss Jr, born in 1946. Dorothy died on November 17, 1991 in a car accident, in which Desmond was driving and lost control of the vehicle. It was a devastating loss. Doss remarried on July 1, 1993, to Frances May Duman. In March of 2006, he was hospitalized for difficulty breathing. Doss died on March 23, 2006, at his home in Piedmont, Alabama.

These days, we are all used to having a female doctor taking care of us. Those who haven’t are, nevertheless, not opposed to it. Others really don’t want a male doctor. It’s not a gender issue exactly, but there are women who just don’t feel comfortable with a male doctor, and men who don’t feel comfortable with a female doctor. We might have thought that this would not still be an issue all these years later, but it can be. As long as people are uncomfortable with their bodies, this might be the case.

These days, we are all used to having a female doctor taking care of us. Those who haven’t are, nevertheless, not opposed to it. Others really don’t want a male doctor. It’s not a gender issue exactly, but there are women who just don’t feel comfortable with a male doctor, and men who don’t feel comfortable with a female doctor. We might have thought that this would not still be an issue all these years later, but it can be. As long as people are uncomfortable with their bodies, this might be the case.

In the 1800s, however, this was not just an issue of discomfort, it was just not done. Mary E Walker was born in 1832, in Oswego Town near Oswego, New York. She was never one, to “hide her light,” but rather always stood out in a crowd. Even as a child, she was distinguished for her strength of mind and her decision of character. She grew into a very independent woman. Mary wanted to be useful. She had no desire to sit at home and be “just a housewife.” Mary was a feminist before most people knew what that was. She always had great energy, and in her early years, she wore bloomers, the pantaloon style garb of the radical feminists of the age. She decided to go to medical school, and when she graduated in 1855, she was the only female in her class from Syracuse Medical College. After graduation, she became one of the few women physicians in the country.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Dr Walker, who was 29 years old by then, journeyed to Washington DC and applied for an appointment as an Army surgeon. Of course, the Medical Department was…shocked, to put it mildly, and they quickly rejected her…with considerable verbosity. “A woman’s place is in the home,” or “No one will go to a woman doctor!” Dr Walker was not a woman who could be so easily discouraged. She stayed in Washington, and even served as an unpaid volunteer in various camps. Who would do that, and how did she survive without pay. Then, when the patent office was converted into a hospital, Walker served as assistant surgeon…again, without pay. During her time in the patent-office-turned-hospital, she was instrumental in establishing an organization that aided needy women who came to Washington to visit wounded relatives. It was a need that no one really thought about until she did, and it was probably reminiscent on the modern-day Ronald McDonald House.

As good as she was, Walker was not immune to considerable amounts of abuse over her persistent demands to be made a surgeon. Still, they could not dispute the fact that she also earned considerable respect for her many good works. It was about this time that she decided to abandon the bloomers and adopt a modified version of male attire, with a calf length skirt worn over trousers. She kept her hair relatively long and curled  so that anyone could know she was a woman. While she wore a modified version of men’s clothes, she wanted everyone to know that she was a woman. She would not mask her talents by pretending to be a man.

so that anyone could know she was a woman. While she wore a modified version of men’s clothes, she wanted everyone to know that she was a woman. She would not mask her talents by pretending to be a man.

Finally, in November 1862, Dr Mary E Walker presented herself at the Virginia headquarters of MG Ambrose Burnside, and was taken on as a field surgeon. She was still a volunteer, but she was a titled surgeon. She treated the wounded at Warrenton and in Fredericksburg in December 1862. Almost a year later, she was in Chattanooga, Tennessee, tending the casualties of the battle of Chickamauga. After the battle, she again requested a commission as an Army doctor, such a simple thing after her years of loyal service, I would think. In September 1863, MG George H Thomas appointed her as an assistant surgeon in the Army of the Cumberland, assigning her to the 52nd Ohio Regiment. Finally, she had her commission. Now, many stories were told of her bravery under fire. Suddenly, it was ok to talk about just how incredible she was.

Sadly, she served with the 52nd Ohio Regiment for only a short time. In April 1864, Walker was captured by Confederate troops. She had stayed behind to tend wounded following a Union retirement. The Confederates charged her with being a spy and arrested her. The spy accusation came about as a result of her male attire. They said it constituted the principal evidence against her. Dr Walker spent the next four months in various prisons, being subjected to much abuse for her “unladylike” occupation and attire, until she was exchanged for a Confederate surgeon in August 1864.

In October of the same year, the Medical Department granted Dr Walker a contract as an acting assistant surgeon. Finally, 3 years after she first showed up on their doorstep she was given the rank and pay she deserved. Still, despite her requests for battlefield duty, she was not sent into the field again. She spent the rest of the war as superintendent at a Louisville, Kentucky, female prison hospital and a Clarksville, Tennessee orphanage. After she was released from her government contract at the end of the war, Walker lobbied for a brevet promotion to major for her services. Typically, Secretary of War Stanton would not grant the request. Finally, President Andrew Johnson asked for another way to recognize her service. A Medal of Honor was presented to Dr Walker in January 1866. She wore it every day for the rest of her life. She continued in the women’s rights movement and also crusaded against immorality, alcohol and tobacco, and for clothing and election reform. One of her more unusual positions was that there was no need for a women’s suffrage act, as women already had the vote as American citizens. Her taste in clothes never changed, and caused her frequent arrests on such charges as impersonating a man. At one trial, she asserted her right to, “Dress as I please in free America on whose tented fields I have served for four years in the cause of human freedom.” The judge  dismissed the case and ordered the police never to arrest Dr Walker on that charge again. She left the courtroom to hearty applause.

dismissed the case and ordered the police never to arrest Dr Walker on that charge again. She left the courtroom to hearty applause.

In 1916, Congress revised the Medal of Honor standards to include only actual combat with an enemy. Several months later, in 1917, the Board of Medal Awards, after reviewing the merits of the awardees of the Civil War awards, ruled Dr Walker’s medal, as well as those of 910 other recipients, as unwarranted and revoked them. It was an insult of the highest degree, and even after her death on February 21, 1919 at the age of 86, it was not to be forgotten. Nearly 60 years after her death, one of her descendants urged the Army Board for Correction of Military Records to review the case. On June 19, 1977, Army Secretary Clifford Alexander approved the recommendation to restore the Medal of Honor to Dr Mary E Walker. It was the right thing to do. Walker remains the sole female recipient of the Medal of Honor.

In a war, there are many heroes, and all too often, many of them are unsung heroes, who heroic acts all but go unnoticed. Lieutenant Colonel Matt Urban was one of those heroes, who actually became an Urban Legend, because of his uncanny ability to seemingly come back from the dead. Urban was one of the most decorated American officers of World War II. He fought in seven campaigns and was wounded seven times. Each time he was wounded, he seemingly came back to life…so often, in fact, that the Germans gave him the nickname “the Ghost.” When he was given the Medal of Honor, his citation referred to ten separate acts of bravery during the Normandy campaign alone.

In a war, there are many heroes, and all too often, many of them are unsung heroes, who heroic acts all but go unnoticed. Lieutenant Colonel Matt Urban was one of those heroes, who actually became an Urban Legend, because of his uncanny ability to seemingly come back from the dead. Urban was one of the most decorated American officers of World War II. He fought in seven campaigns and was wounded seven times. Each time he was wounded, he seemingly came back to life…so often, in fact, that the Germans gave him the nickname “the Ghost.” When he was given the Medal of Honor, his citation referred to ten separate acts of bravery during the Normandy campaign alone.

To name a few of the heroic and maybe just a little bit crazy acts of bravery, Urban took on multiple enemy tanks with a bazooka, all while walking on a cane because he’d broken his leg landing on Utah Beach. He organized multiple counterattacks after nearly having his leg blown off, then breaking himself out of the hospital, hitchhiking to the front, immediately throwing himself into battle, running into an abandoned tank and driving it toward the enemy line with no crew!! He was wounded again and again, but refused to be evacuated. Finally, a bullet in the throat took him out of combat for good. His reign of terror  against the Germans was over, but not his life. Once again, the Germans couldn’t kill “the Ghost.” Urban recovered, survived the war, and lived until 1995. Urban died on March 4, 1995, in Holland, Michigan, at the age of 75. The cause of death was a collapsed lung, reportedly due to his war injuries. He is buried in Plot: Section 7a, Grave 40 at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.

against the Germans was over, but not his life. Once again, the Germans couldn’t kill “the Ghost.” Urban recovered, survived the war, and lived until 1995. Urban died on March 4, 1995, in Holland, Michigan, at the age of 75. The cause of death was a collapsed lung, reportedly due to his war injuries. He is buried in Plot: Section 7a, Grave 40 at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.

“Matt Louis Urban was a highly decorated United States Army combat soldier who served with distinction as an infantry officer in the Mediterranean and European Theater of Operations during World War II. He scouted, led charges upfront, and performed heroically in combat on several occasions despite being wounded. He retired after World War II as a lieutenant colonel. Urban received over a dozen individual decorations for combat from the U.S. Army, including seven Purple Hearts. In 1980, he received the Medal of Honor and four other individual decorations for combat belatedly for his actions in France and Belgium in 1944. In Section 7a of the “Prominent Military Figures”

Matt Urban was born Matthew Louis Urbanowicz in Buffalo, New York, to Polish immigrant Stanley Urbanowicz,  a plumbing contractor. His mother Helen was born in Depew, New York. He attended East High School in Buffalo, and graduated in 1937. Urban had three brothers: Doctor Stanley (Urbanowicz) Urban, Arthur (Urbanowicz) Urban, and Eugene, who died in 1927 from appendicitis. In the fall of 1937, he enrolled at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, majoring in history and government with a minor in community recreation. He graduated on June 14, 1941, with a Bachelor of Arts degree. For reasons unknown, he used the name Matty L. Urbanowitz during his last year of college. While at Cornell University, he was a member of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC), the track and boxing teams, and the Kappa Delta Rho fraternity. Nevertheless, his greatest accomplishment was that of the Urban Legend known as “the Ghost.”

a plumbing contractor. His mother Helen was born in Depew, New York. He attended East High School in Buffalo, and graduated in 1937. Urban had three brothers: Doctor Stanley (Urbanowicz) Urban, Arthur (Urbanowicz) Urban, and Eugene, who died in 1927 from appendicitis. In the fall of 1937, he enrolled at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, majoring in history and government with a minor in community recreation. He graduated on June 14, 1941, with a Bachelor of Arts degree. For reasons unknown, he used the name Matty L. Urbanowitz during his last year of college. While at Cornell University, he was a member of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC), the track and boxing teams, and the Kappa Delta Rho fraternity. Nevertheless, his greatest accomplishment was that of the Urban Legend known as “the Ghost.”

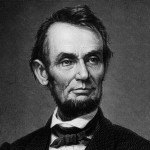

In a war, there are many heroes…some whose acts of courage and selflessness were so amazing that many felt they needed to receive a different medal…one that paid homage to the incredible things they did. Often these medals were even given posthumously because the brave act of the hero, cost the recipients their lives. Before 1861, no such medal existed. President Abraham Lincoln didn’t think that was right. There were many brave soldiers, and while not all brave acts would qualify for the medal of honor, the most self sacrificing of them would…the ones who set aside their own safety to protect the lives of others.

In a war, there are many heroes…some whose acts of courage and selflessness were so amazing that many felt they needed to receive a different medal…one that paid homage to the incredible things they did. Often these medals were even given posthumously because the brave act of the hero, cost the recipients their lives. Before 1861, no such medal existed. President Abraham Lincoln didn’t think that was right. There were many brave soldiers, and while not all brave acts would qualify for the medal of honor, the most self sacrificing of them would…the ones who set aside their own safety to protect the lives of others.

For that reason, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law a measure calling for the awarding of a US Army Medal of Honor, in the name of Congress, “to such noncommissioned officers and privates as shall most distinguish themselves by their gallantry in action, and other soldier-like qualities during the present insurrection.” The previous December, Lincoln had approved a provision creating a US Navy Medal of Valor, which was the basis of the Army Medal of Honor created by Congress on July 12, 1862. War puts men and women into situations whereby the only choices are kill or be killed. That can be a scary proposition. These soldiers do not do what they do in order to receive a medal. In fact, a medal rarely crosses their minds at all. The first US Army soldiers to receive what would become the nation’s highest military honor were six members of a Union raiding party who in 1862 penetrated deep into Confederate territory to destroy bridges and railroad tracks between Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Atlanta, Georgia.

In 1863, the Medal of Honor was made a permanent military decoration available to all members, including commissioned officers, of the US military. It is conferred upon those who have distinguished themselves in actual combat at risk of life beyond the call of duty. Since its creation, during the Civil War, more than 3,400

men and one woman, Dr Mary Walker, have received the Medal of Honor for heroic actions in US military conflict. These people gave whatever it took to perform their duties. They were the best of the best, and the medal of honor was the best honor we could bestow on them. Of course, in Lincoln’s time, there was no air force, so that medal came later, as did the medals from the other branches of service, including the Coast Guard.

men and one woman, Dr Mary Walker, have received the Medal of Honor for heroic actions in US military conflict. These people gave whatever it took to perform their duties. They were the best of the best, and the medal of honor was the best honor we could bestow on them. Of course, in Lincoln’s time, there was no air force, so that medal came later, as did the medals from the other branches of service, including the Coast Guard.

The pilots of the war birds were brave men. They were tasked with staying the course while under heavy anti-aircraft fire and flak. That would be a major undertaking for most of us because in that situation, all our mind can think to do is to turn and run. These men had to stay in place so they could make the bomb runs, or protect those who were. Of course, there were gunners tasked with keeping the enemy planes at bay, but they couldn’t fly the plane to get you home.

The pilots of the war birds were brave men. They were tasked with staying the course while under heavy anti-aircraft fire and flak. That would be a major undertaking for most of us because in that situation, all our mind can think to do is to turn and run. These men had to stay in place so they could make the bomb runs, or protect those who were. Of course, there were gunners tasked with keeping the enemy planes at bay, but they couldn’t fly the plane to get you home.

United States Army Air Force Lieutenant William R Lawley Jr, was a pilot on a B-17 Bomber on February 20, 1944. It was the first day of “Big Week,” and Lieutenant Lawley’s Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress was at the head of a formation of one thousand bombers sent to bomb Germany’s production and aircraft manufacturing facilities. “Big Week” was the Allied plan to spend seven days ruthlessly dropping explosives onto enemy aircraft production facilities deep behind enemy lines. Day and night, wave after wave of American B-17 Flying Fortresses, B-24 Liberators, and British Lancasters blasted shipyards, railroad junctions, power plants, airfields, steel production facilities, dams, and military bases relentlessly, igniting everything from ball bearing plants to oil refineries up into towering explosive fireballs, to make it impossible for anyone in Germany to build a working fighter plane.

Suddenly, the call rang out, “Bandits, incoming, three o’clock high!” Immediately, the gunners began shooting to fight off the enemy planes, while Lawley held the plane steady. The loud, rumbling propellers roared as he pushed open the throttle and smashed through a thick black cloud of anti-aircraft smoke at nearly three hundred miles an hour, all while keeping in tight formation with hundreds of other B-17s. A pair of Nazi Focke-Wulf 190 fighter planes screamed by, ripping off thousands of rounds from twin-linked machine guns and heavy 20mm autocannons. Black puffs of enemy artillery popped up all around Lawley’s massive aircraft craft. The enemy fighters screamed past at speeds of over four hundred miles an hour. As the gray Nazi fighters dove down towards another squadron of American bombers below, Lawley’s starboard waist gunner zeroed in on them with his .50-caliber machine gun with a quick burst of tracer fire, but had to release the trigger as a pair of American P-47 Thunderbolt fighter planes dropped in to chase them. These Bomber raids were nothing new for Lawley. Born in Alabama, this 23 year old veteran pilot had already flown nine missions over Germany in the last year. This was his tenth mission, but the first at the controls of a brand-new B-17, nicknamed Cabin in the Sky III, because the first two Cabin in the Sky aircraft been blown up.

Suddenly, voices on the intercom called out enemy fighters, this time diving down from behind. With the sun at their backs, blinding the tail gunner, the Focke-Wulfs ignored the deadly clouds of flak ripping apart the sky around them and hurtled straight into the B-17 formation. Their 20mm cannons struck home at one of Lawley’s wingmen, catching her engines on fire and dropping her out of the sky like a brick. Another flak explosion hit even closer, rocking Cabin in the Sky III and peppering one of the engines with shards of metal, causing it to burst into flames. Lawley ordered the copilot to shut it down and kept moving. More calls came in. “Six o’clock low.” “Three o’clock level.” The Nazis were everywhere, attacking from seemingly every direction at once. The B-17s stuck close together, knowing that the only way to survive was to stay close and lay down heavy fields of  machine gun fire. As his gunners fired in every direction, Lawley looked through his cockpit window to see a fleet of twenty or so 190s drop down in front of him, pick out targets, and open fire. With a deafening crash, a 20mm high explosive autocannon shell bust through the front window of the pane, exploding in the cockpit. Everything went black.

machine gun fire. As his gunners fired in every direction, Lawley looked through his cockpit window to see a fleet of twenty or so 190s drop down in front of him, pick out targets, and open fire. With a deafening crash, a 20mm high explosive autocannon shell bust through the front window of the pane, exploding in the cockpit. Everything went black.

Lawley snapped awake seconds later, his ears ringing. Alarms were going off all across his console, which was now riddled with shards of shrapnel. His right arm was shattered. Through blurry vision, Lawley saw his co-pilot slumped over dead, his body laying on the control stick pushing it forward, putting the plane was in a steep dive. The loaded bomb racks made matters worse. The pilot-side window was smashed, and broken glass had gone into Lawley’s face, arms, and side. The windshield was so smeared with blood and oil that he could barely see out of it. Another engine was one fire. Lieutenant William Lawley didn’t panic. He did his job. Determined to keep his plane and his crew alive, the veteran USAAF pilot reached out with his shattered right arm, grabbed his dead co-pilot, and somehow pulled him back off the controls. Then, with just his left hand, he manually fought a 15-ton bomber aircraft out of a ninety-degree nosedive at 12,000 feet, leveled it off, and shut down the second burning engine. Looking up, he saw the Focke-Wulf pilots circling around for another pass, so this grim warrior made an evasive turn, dove the plane down into the cloud cover, and accelerated out of there as fast as he could. Other B-17s in the formation had radioed Cabin in the Sky III as Killed in Action, but somehow William Lawley managed to evade the enemy fighters and get the heck out of Leipzig. He flew across Germany, dodging enemy AA positions, then flew in low over the French countryside and ordered the surviving eight members of his crew to grab parachutes and bail out. It was then that he learned all eight crewmen were wounded in the attack, and that two of them were hurt so bad they couldn’t possibly go skydiving right now. Lawley said, “Ok. I’m going to get us home then.” Nobody jumped out of the plane.

The bombardier eventually got the racks unstuck and released his bombs over an unimportant part of the French countryside, but before long another squadron of Me-109 fighters picked up the wounded B-17 on radar and came swooping in for the kill. With his guys running to their guns to bark .50-caliber machine gun fire, Lawley hammered the stick of his crippled plane, dodging and evading with one arm and somehow eluding enemy fighters one more time. In the process, however, he had to use more fuel than he’d have liked, and one of the two remaining engines was now almost completely out of gas. Once the coast was clear and the Messerschmitt fighter planes were gone, Lawley leveled off the plane and promptly passed out from loss of blood. This was the days before autopilot, and Lawley was the only guy who knew how to fly the plane. Luckily his navigator figured out what was up and woke him up pretty much right away.

Cabin in the Sky III somehow reached the English Channel against all odds, received emergency landing permission from a Canadian fighter base on the English coast and, just in case you’re wondering how the heck this could possibly get any worse, when William Lawley hit the button to drop his landing gear, it didn’t deploy. So, limping in with three burned-out engines, “feathering” his only working one by pumping it off and on with small amounts of gas, half blinded by broken glass, exhausted from loss of blood, and with no landing gear, eight wounded crew members, and one good arm, Lieutenant William Lawley attempted to crash land a 15-ton B-17 on a grass airfield about the size of a soccer pitch. He came in hard on his belly, sliding across the airfield, finally coming to a rest just outside the Canadian barracks. Every member of his crew survived. Lawley walked out of the wreckage, spend a few weeks in the hospital, and make a full recovery. He successfully piloted four more bombing missions before the war was over. Did he earn his Modal of Honor? Without a doubt!!