massachusetts

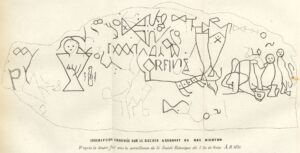

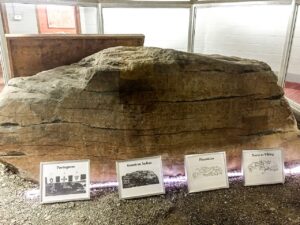

The Dighton Rock is a 40-ton boulder that was found in the riverbed of the Taunton River at located Berkley, Massachusetts, over 300 years ago. The rock has puzzling petroglyphs on it that have apparently never been able to be deciphered. Dighton Rock is one of the greatest mysteries of Massachusetts. The boulder is slanted and has six sides. It is approximately 5′ high, 9½’ wide, and 11′ long. All of those 300 years, people have wondered about the lines, geometric shapes, drawings, and writing that appear on the rock and who created them. They wanted to figure it out. What did it mean? Who made those markings, so many years ago. No one really knows how long ago the marks were made, only about how long ago it was found.

The Dighton Rock is a 40-ton boulder that was found in the riverbed of the Taunton River at located Berkley, Massachusetts, over 300 years ago. The rock has puzzling petroglyphs on it that have apparently never been able to be deciphered. Dighton Rock is one of the greatest mysteries of Massachusetts. The boulder is slanted and has six sides. It is approximately 5′ high, 9½’ wide, and 11′ long. All of those 300 years, people have wondered about the lines, geometric shapes, drawings, and writing that appear on the rock and who created them. They wanted to figure it out. What did it mean? Who made those markings, so many years ago. No one really knows how long ago the marks were made, only about how long ago it was found.

The rock has been studied by many people over the years. In 1680, English colonist Reverend John Danforth drew a copy of the petroglyphs. That drawing has been preserved in the British Museum, but there are conflicts as to the accuracy of the drawing. Some say the markings aren’t exactly the same as the rock. In something as intricate as petroglyphs, accuracy would be of vital importance. Ten years later, in 1690 Reverend Cotton Mather described the rock in his book, The Wonderful Works of God Commemorated: “Among the other Curiosities of New England, one is that of a mighty Rock, on a perpendicular side whereof by a River, which at High Tide covers part of it, there are very deeply Engraved, no man alive knows How or When about half a score Lines, near Ten Foot Long, and a foot and half broad, filled with strange Characters: which would suggest as odd Thoughts about them that were here before us, as there are odd Shapes in that Elaborate Monument…”

One theory suggests that Indigenous peoples of North America…who were known to have inscribed petroglyphs in rocks (a schematic face on the Dighton Rock is similar to an Indian petroglyph in Eastern Vermont) made the markings. A second theory suggests that Ancient Phoenicians made them was proposed in 1783 by Ezra Stiles in his “Election Sermon” as the “descendants of the sons of Japheth.” Still another theory suggests that the Norse might have made them. That theory was proposed by Carl Christian Rafn in 1837, but it was rejected by archaeologists such as TD Kendrick and Kenneth Feder. Others suggested that the Portuguese may have made them. That was proposed in 1912 by Edmund B Delabarre, who (after seeing Portuguese writing) believed that they then used the rock for their own inscriptions. Delabarre wrote that “markings on the Dighton Rock suggest that Miguel Corte-Real reached New England. Delabarre stated that the markings were abbreviated Latin, and the message, translated into English, reads as follows: “I, Miguel Cortereal, 1511. In this place, by the will of God, I became a chief of the Indians.'” Of his findings, Douglas Hunter wrote in his book “Reconstructing the

history of writing about Dighton Rock” provides copious evidence and analysis debunking the Corte-Real origin myth. Lastly, the Chinese have also been suggested as a possible source, proposed by Gavin Menzies in his 2002 book “1421: The Year China Discovered America.” I don’t think we’ll ever know who made them or what they mean.

history of writing about Dighton Rock” provides copious evidence and analysis debunking the Corte-Real origin myth. Lastly, the Chinese have also been suggested as a possible source, proposed by Gavin Menzies in his 2002 book “1421: The Year China Discovered America.” I don’t think we’ll ever know who made them or what they mean.

If King George III was hoping to keep the New England colonies dependent on the British by placing taxes, restrictions, lockdowns, and the New England Restraining Act on them, he greatly underestimated the colonists. The New England Restraining Act was endorsed by King George III on March 30, 1775. The Act required New England colonies to trade exclusively with Great Britain as of July 1, 1775, with an additional rule going into effect on July 20, banning colonists from fishing in the North Atlantic.

If King George III was hoping to keep the New England colonies dependent on the British by placing taxes, restrictions, lockdowns, and the New England Restraining Act on them, he greatly underestimated the colonists. The New England Restraining Act was endorsed by King George III on March 30, 1775. The Act required New England colonies to trade exclusively with Great Britain as of July 1, 1775, with an additional rule going into effect on July 20, banning colonists from fishing in the North Atlantic.

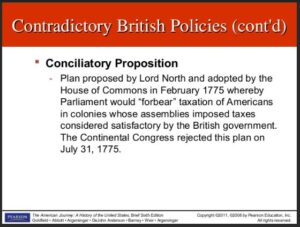

The Restraining Act and the Conciliatory Proposition were introduced to Parliament by British prime minister, Frederick, Lord North, on the same day. The Conciliatory Proposition promised that no colony that met its share of imperial defenses and paid royal officials’ salaries of their own accord would be taxed…a ridiculous statement, because the very act of making the forced payments was basically taxing. Supposedly, the British were  conceding to the colonists’ demand that they be “allowed to provide the crown with needed funds on a voluntary basis.” Through the preposition, Parliament would ask for money through requisitions, not demand it through taxes. If you ask me, that is a distinction without a difference. Either way, the colonists were forced to pay for things they shouldn’t have to. The Restraining Act was meant to appease Parliamentary hardliners, who would otherwise have impeded passage of the pacifying proposition. So, Lord North had to work both sides against the middle to get the Conciliatory Proposition passed.

conceding to the colonists’ demand that they be “allowed to provide the crown with needed funds on a voluntary basis.” Through the preposition, Parliament would ask for money through requisitions, not demand it through taxes. If you ask me, that is a distinction without a difference. Either way, the colonists were forced to pay for things they shouldn’t have to. The Restraining Act was meant to appease Parliamentary hardliners, who would otherwise have impeded passage of the pacifying proposition. So, Lord North had to work both sides against the middle to get the Conciliatory Proposition passed.

Unfortunately for North and prospects for peace, General Thomas Gage had already received orders from London to march on Concord, Massachusetts. His orders were to destroy the armaments stockpiled in the town and take Patriot leaders John Hancock and Samuel Adams into custody. Gage had received the orders in January 1775 and arrived in Boston before the Conciliatory Proposition, meaning that he didn’t know about the  agreement made to stop the taxing of the colonists. So, on April 18, 1775, an army of 700 Redcoats marched towards Concord Bridge. It was basically the last straw…the military action that would lead to the Revolutionary War, the birth of the United States as a new nation, the temporary downfall of Lord North, and the near abdication of King George III. The Treaty of Paris marked the end of the conflict and guaranteed New Englanders the right to fish off Newfoundland. It was the very right denied them by the New England Restraining Act. The British learned that they could only push the colonists so far, and then they would lose control of the very people they tried to enslave.

agreement made to stop the taxing of the colonists. So, on April 18, 1775, an army of 700 Redcoats marched towards Concord Bridge. It was basically the last straw…the military action that would lead to the Revolutionary War, the birth of the United States as a new nation, the temporary downfall of Lord North, and the near abdication of King George III. The Treaty of Paris marked the end of the conflict and guaranteed New Englanders the right to fish off Newfoundland. It was the very right denied them by the New England Restraining Act. The British learned that they could only push the colonists so far, and then they would lose control of the very people they tried to enslave.

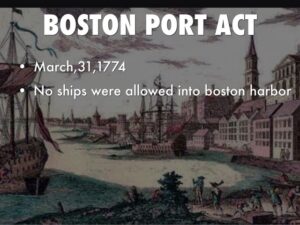

After the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, the tensions between the British Parliament and the American Colonies seethed for months. Then, on March 25, 1774, the British Parliament took the next step in its reign of tyranny, when it passed the Boston Port Act. The Boston Port Act closed the port of Boston to all incoming and outgoing ships, while demanding that the city’s residents pay for the nearly $1 million worth (in today’s money) of tea dumped into Boston Harbor during the Boston Tea Party. The act basically held the city under siege, while demanding a ransom for its release.

After the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, the tensions between the British Parliament and the American Colonies seethed for months. Then, on March 25, 1774, the British Parliament took the next step in its reign of tyranny, when it passed the Boston Port Act. The Boston Port Act closed the port of Boston to all incoming and outgoing ships, while demanding that the city’s residents pay for the nearly $1 million worth (in today’s money) of tea dumped into Boston Harbor during the Boston Tea Party. The act basically held the city under siege, while demanding a ransom for its release.

The Boston Port Act was the first and easiest to enforce of the four acts that resulted from the Boston Tea Party. Together, there were four acts, and they were known as the Coercive Acts. The other three were a new Quartering Act, the Administration of Justice Act, and the Massachusetts Government Act. These were passed as part of the Crown’s attempt to intimidate Boston’s increasingly unruly residents. King George III appointed General Thomas Gage, who commanded the British army in North America, as the new governor of Massachusetts in 1774, before the Massachusetts Government Act revoked the colony’s 1691 charter and curtailed the powers of the traditional town meeting and colonial council. Probably the biggest mistake the British made was in not understanding that the main reason the colonists left Britain was to get far enough away from Crown rule to live their own lives. These acts made it very clear to Bostonians that the crown intended to impose martial law, and that was something they just would not stand for.

Gage got right down to business, when in June, he easily sealed the ports of Boston and Charlestown using the formidable British navy. This act left merchants terrified of impending economic disaster. In their panic, many merchants simply wanted to pay for the tea and disband the Boston Committee of Correspondence, which had served to organize anti-British protests. Little did they know that to “bend their knees” to the tyranny would only have served to make matters worse. People make big mistakes when they get in fear. The merchants tried to convince their neighbors to appease the British in the hope of everything just “going away,” but that would never have been the case. A town meeting was called to discuss the matter, and the idea was immediately voted down by a substantial margin.

Parliament hoped that the Coercive Acts would isolate Boston from Massachusetts, Massachusetts from New England, and New England from the rest of North America, thereby preventing unified colonial resistance to the

British. Again, they misjudged the colonists, and their effort backfired. Rather than abandon Boston, the colonial population shipped much-needed supplies to Boston and formed extra-legal Provincial Congresses to mobilize resistance to the crown. By the time Gage attempted to enforce the Massachusetts Government Act, his authority had eroded beyond repair. It was another “shot to the heart” of the crown, that would ultimately lead to their complete downfall.

British. Again, they misjudged the colonists, and their effort backfired. Rather than abandon Boston, the colonial population shipped much-needed supplies to Boston and formed extra-legal Provincial Congresses to mobilize resistance to the crown. By the time Gage attempted to enforce the Massachusetts Government Act, his authority had eroded beyond repair. It was another “shot to the heart” of the crown, that would ultimately lead to their complete downfall.

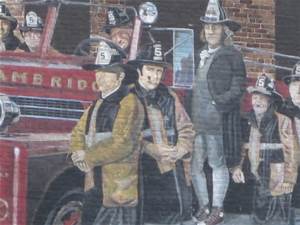

One of the saddest realities is that safety standards are often the result of a tragedy. That is exactly what happened during what is still the deadliest nightclub fire in the world, and the second-deadliest single-building fire…after the Iroquois Theatre fire. On November 28, 1942, Cocoanut Grove was well known as one of Boston’s most popular nightspots. The club attracted many celebrity guests and Boston’s most elite citizens. The fire was a tragedy that later became the catalyst for change in fire prevention, and how to survive a fire. Unfortunately, 492 people have to pay for these lessons with their lives.

One of the saddest realities is that safety standards are often the result of a tragedy. That is exactly what happened during what is still the deadliest nightclub fire in the world, and the second-deadliest single-building fire…after the Iroquois Theatre fire. On November 28, 1942, Cocoanut Grove was well known as one of Boston’s most popular nightspots. The club attracted many celebrity guests and Boston’s most elite citizens. The fire was a tragedy that later became the catalyst for change in fire prevention, and how to survive a fire. Unfortunately, 492 people have to pay for these lessons with their lives.

The Cocoanut Grove was owned by Barnet “Barney” Welansky, who was closely connected to the Mafia and to Mayor Maurice J Tobin. As often happens, anyone connected to the Mafia and/or a politician, also believes they are above the law. They do things the way they want to, cutting corners to save a buck, and then they expect their connections to get them out of trouble when and if it shows up. Welansky was no different. In the building and running of his nightclub, fire regulations had been pretty much disregarded, because as we all know, regulations are for other people to follow, but not, in this case, the Cocoanut Grove. There was a constant concern about people sneaking in the exit doors, so rather than pay for security to prevent such actions, some exit-doors had been locked to prevent said unauthorized entry. The decor wasn’t always checked for safety either, like the elaborate palm tree décor, which contained flammable materials. Also, because of wartime shortages of freon, the air-conditioning used flammable gas to cool the club. Welansky often disregarded the capacity laws to bring in bigger profits, and so it was that during the first Thanksgiving weekend since the United States had entered World War II, the Grove was filled to more than twice its legal capacity.

When disaster struck, it was in the form of a fire that was initiated by an electrical short and fueled by methyl chloride in the air conditioning unit. Once it started, the fire and its associated smoke spread rapidly through all

areas of the club. The problem…people were unable to escape due in part to locked exit doors. The only saving grace was that the local hospitals were especially well prepared to treat the casualties, because they had been rehearsing emergency drills in response to possible wartime attacks on the East Coast. Had that not been the case, the death toll would have likely included the 130 survivors too. If “good” can be said to come from tragedy, it would come in the form of the demonstrated value of the new blood banks and stimulated important advances in the treatment of burn victims. As always happens after a tragedy, many new laws were enacted for public establishments, including the banning of flammable decorations, a provision that emergency exits must be kept unlocked (from the inside), and that revolving doors cannot be the only exit.

areas of the club. The problem…people were unable to escape due in part to locked exit doors. The only saving grace was that the local hospitals were especially well prepared to treat the casualties, because they had been rehearsing emergency drills in response to possible wartime attacks on the East Coast. Had that not been the case, the death toll would have likely included the 130 survivors too. If “good” can be said to come from tragedy, it would come in the form of the demonstrated value of the new blood banks and stimulated important advances in the treatment of burn victims. As always happens after a tragedy, many new laws were enacted for public establishments, including the banning of flammable decorations, a provision that emergency exits must be kept unlocked (from the inside), and that revolving doors cannot be the only exit.

The investigation centered around Welansky’s blatant disregard for the safety of the very patrons who gave him his wealth by their continued patronage of his establishment. An official report revealed that “the Cocoanut Grove had been inspected by a captain in the Boston Fire Department (BFD) just ten days before the fire and declared safe. Further, it was found that the Grove had not obtained any licenses for operation for several years. There were no food handlers’ permits and no liquor licenses. Stanley Tomaszewski, the busboy who had allegedly started the fire, was underage and should not have been working there. Moreover, the recent remodeling of the Broadway Lounge had been done without building permits, using unlicensed contractors.” Tomaszewski testified at the inquiry and was exonerated, as he was not responsible for the flammable decorations or the life safety code violations. While declared innocent, Tomaszewski would pay for the “crime” anyway, in the form of being “ostracized for much of his life because of the fire.” Tomaszewski died in 1994. In the end, the blame was rightly assigned to Welansky, for violation of the existing safety standards, and upon

his conviction in 1943, Welansky was sentenced to 12–15 years in prison. Welansky served nearly four years before being quietly pardoned by Tobin, who had been elected governor of Massachusetts since the fire. In December 1946, diagnosed with cancer, Welansky was released from Norfolk Prison, telling reporters, “I wish I’d died with the others in the fire.” Nine weeks later on 27 Jan 1947 the cancer took his life. He was 49 years old.

his conviction in 1943, Welansky was sentenced to 12–15 years in prison. Welansky served nearly four years before being quietly pardoned by Tobin, who had been elected governor of Massachusetts since the fire. In December 1946, diagnosed with cancer, Welansky was released from Norfolk Prison, telling reporters, “I wish I’d died with the others in the fire.” Nine weeks later on 27 Jan 1947 the cancer took his life. He was 49 years old.

Lizzie Borden was a unique character for her era, in that the thing that most people remember about her was her arrest and trial for the axe murders of her father and stepmother in 1892. While many people believe she was guilty of the murders, she was actually acquitted in 1893. For whatever reason, the case against her was such that it could not be proven “without a shadow of a doubt,” which is the requirement for a conviction.

Lizzie Borden was a unique character for her era, in that the thing that most people remember about her was her arrest and trial for the axe murders of her father and stepmother in 1892. While many people believe she was guilty of the murders, she was actually acquitted in 1893. For whatever reason, the case against her was such that it could not be proven “without a shadow of a doubt,” which is the requirement for a conviction.

Lizzie Borden was born on July 19, 1860, in Fall River, Massachusetts. Lizzie Borden and her sister, Emma, were born to Andrew and Sarah Borden. Sarah Borden died a short time after Lizzie’s birth. The girls lived with their father, Andrew Borden who married a woman named Abby Durfee Gray, three years after Sarah’s passing. The relationship between the girls and their stepmother was not a close one, in fact, they greeted her as “Mrs. Borden” and worried that Abby Borden’s family sought to gain access to their father’s money. Emma was protective of her younger sister and, together, the two sisters helped to manage the rental properties owned by Andrew Borden. The family attended the Congregationalist Church, an institution in which Lizzie was particularly involved. The family lived well. Andrew Borden was successful enough in the fields of manufacturing and real estate development to support his wife and two daughters, Emma and Lizzie quite comfortably. He also employed servants to keep their home in order. Both Emma and Lizzie lived with their father and stepmother into adulthood.

On August 4, 1892, Andrew and Abby Borden were found murdered in their home. Of course, as is common, the family is questioned in these cases, and in the end, Lizzie was arrested and tried for the axe murders. It seems strange to me that after living with the couple for almost thirty years, Lizzie would suddenly decide that  she didn’t need them anymore…especially since her dad was so financially successful, and his death could bring an end to that financial security. Nevertheless, it’s hard to say what can push someone over the edge. I guess the jury must have agreed with my own train of thought because Lizzie was found not guilty. Even with the trial and the trauma of all that happened, Lizzie continued to live in Fall River until her death, on June 1, 1927. The murders of her father and stepmother were never solved.

she didn’t need them anymore…especially since her dad was so financially successful, and his death could bring an end to that financial security. Nevertheless, it’s hard to say what can push someone over the edge. I guess the jury must have agreed with my own train of thought because Lizzie was found not guilty. Even with the trial and the trauma of all that happened, Lizzie continued to live in Fall River until her death, on June 1, 1927. The murders of her father and stepmother were never solved.

On the morning of August 4, 1892, Andrew and Abby Borden were murdered and mutilated in their Fall River home. It was Lizzie Borden who alerted the maid, Bridget, to her father’s dead body. He had been attacked and killed while sleeping on the sofa. A search of the home led to the discovery of the body of Abby Borden in an upstairs bedroom. Like her husband, Abby Borden was the victim of a brutal hatchet attack. The police were called to the scene of the murders, and they suspected Lizzie immediately. Nevertheless, she was not taken into custody at that time. Her sister, Emma, was out of town at the time and was never a suspect. Apparently, Lizzie burned a dress during the week between the murders and her arrest. She said the dress was stained with paint, so it needed to be burned. The prosecutors believed that the dress was stained with blood, and that Lizzie had burned it to cover up her crime, which is why she was indicted on December 2, 1892. Her widely publicized trial began the following June in New Bedford. Borden did not take the stand in her own defense and her inquest testimony was not admitted into evidence. The testimony provided by others proved inconclusive. On June 20, 1893, Lizzie Borden was acquitted of the murders, and no one else was ever charged with the crimes.

Following the deaths of their dad and stepmom, Lizzie and Emma Borden inherited a significant portion of their father’s estate. They purchased a new home together and lived together for the following decade. Although she was acquitted, Lizzie was considered guilty by many of her neighbors and her reputation was further tarnished when she was accused of shoplifting in 1897. Then in 1905, Emma Borden abruptly moved out of the house that she shared with her sister. While no one ever knew what happened between the sisters, they never spoke

again. Speculation was that Emma may have been uncomfortable with Lizzie’s close friendship with another woman, Nance O’Neil, but she never really said that was the case. Emma’s silence on the matter fueled speculation that she learned new details about the murders of her father and stepmother. The household staff were tight-lipped on the matter and didn’t even offer additional information on the rift following Lizzie’s death. Lizzie Borden died of pneumonia in Fall River, Massachusetts, on June 1, 1927. Strangely, the day Lizzie died, Emma had an accident and broke her hip. She died due to chronic nephritis, 9 days later, on June 10, 1927. The Borden sisters, along with the rest of the family, are buried side by side at the family plot in Oak Grove Cemetery in Fall River.

again. Speculation was that Emma may have been uncomfortable with Lizzie’s close friendship with another woman, Nance O’Neil, but she never really said that was the case. Emma’s silence on the matter fueled speculation that she learned new details about the murders of her father and stepmother. The household staff were tight-lipped on the matter and didn’t even offer additional information on the rift following Lizzie’s death. Lizzie Borden died of pneumonia in Fall River, Massachusetts, on June 1, 1927. Strangely, the day Lizzie died, Emma had an accident and broke her hip. She died due to chronic nephritis, 9 days later, on June 10, 1927. The Borden sisters, along with the rest of the family, are buried side by side at the family plot in Oak Grove Cemetery in Fall River.

Firefighter and Benjamin Franklin…not usually thought of in the same sentence, but really, they should be. In 1736, Benjamin Franklin was already a young man of influence, but his ambitions didn’t stop at just a few. Most of us think of Benjamin Franklin as a scientist, inventor, founding father, prankster, and writer, but firefighter…hmmmmm, not so much. Nevertheless, Benjamin Franklin was a visionary. He saw a problem and decided to fix it.

Firefighter and Benjamin Franklin…not usually thought of in the same sentence, but really, they should be. In 1736, Benjamin Franklin was already a young man of influence, but his ambitions didn’t stop at just a few. Most of us think of Benjamin Franklin as a scientist, inventor, founding father, prankster, and writer, but firefighter…hmmmmm, not so much. Nevertheless, Benjamin Franklin was a visionary. He saw a problem and decided to fix it.

By 1736 Franklin had adopted Philadelphia, Pennsylvania as his home, but during a visit to his hometown of Boston, Massachusetts, he witnessed a fire, and his mind went into overdrive. What he saw was that the safety precautions to keep fire from spreading seemed to be far more advanced in Boston than in Philadelphia. At that time, Philadelphia’s infrastructure was basically a maze of wooden buildings and houses squeezed together in such a way that it was almost like kindling for a bonfire. Franklin saw this decided that something needed to be done. So, he published his findings in his own Philadelphia Gazette. In doing so, he turned up a different kind of heat. Before long, he was able to round up about 30 of his friends and fellow business owners who were interested. So together, the founded the Union Fire Company. Franklin made sure that The Union Fire Company was a non-profit organization…run completely by volunteers. What made this attractive to these business owners is that it was essentially a promise, to always have each other’s backs, if a fire broke out on or close to one of their properties. Not only were they promising to help extinguish the flames and save homes, but each member was required to keep a heavy-duty bag in which to smuggle out any possessions they could salvage as well. It was a code of honor to try, in the midst of disaster, to salvage whatever they could of the lives of the occupants. The Union Fire Company quickly became the biggest fire relief company in the Colonies, or as they later became, the United States.

Never being one to just sit back and tell others what to do, Benjamin Franklin became a volunteer firefighter himself. Soon, there were six volunteer corps established in Philadelphia. This fire company was the first volunteer fire company of its kind in the United States. When people saw how well the system worked, volunteer fire companies sprung up across the city and soon all over the country. We think of Benjamin Franklin

as many things, but in reality, we should maybe think of him as much more than we do. He was the brainchild behind the Great Compromise, which created the Congress we still have today. He was also the first fireman in another way. He “put out the fiery debates” and created a sense of compromise and peace among the founding fathers of our nation too, but he was an actual firefighter in that he actually fought the fires in his city.

as many things, but in reality, we should maybe think of him as much more than we do. He was the brainchild behind the Great Compromise, which created the Congress we still have today. He was also the first fireman in another way. He “put out the fiery debates” and created a sense of compromise and peace among the founding fathers of our nation too, but he was an actual firefighter in that he actually fought the fires in his city.

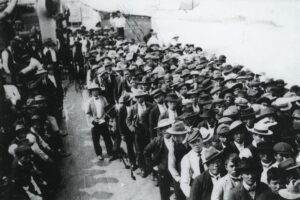

As a young America began to receive immigrants from other countries, it began to achieve its “melting pot” status. It wasn’t until May 7, 1843, that the first Japanese immigrant would arrive on the scene. A young 14-year-old fisherman, named Manjiro in America by way of a whaling ship. It wasn’t really an intentional immigration, because the boy and his fellow crew members were caught in a violent storm that caused their ship to wash up on a desert island 300 miles away from their coastal Japanese village. It was rather a “Gilligan’s Island” kind of situation, except that it didn’t last nearly as long as the famous sitcom.

As a young America began to receive immigrants from other countries, it began to achieve its “melting pot” status. It wasn’t until May 7, 1843, that the first Japanese immigrant would arrive on the scene. A young 14-year-old fisherman, named Manjiro in America by way of a whaling ship. It wasn’t really an intentional immigration, because the boy and his fellow crew members were caught in a violent storm that caused their ship to wash up on a desert island 300 miles away from their coastal Japanese village. It was rather a “Gilligan’s Island” kind of situation, except that it didn’t last nearly as long as the famous sitcom.

After five months on the island, an American whaling ship showed up and rescued Manjiro, who was later adopted by American Captain William Whitfield, who renamed him John Mung and brought him back to the states to his home in Massachusetts. While he was grateful for his rescue, Manjiro always felt drawn to his own country, and eventually returned to Japan. He then became a samurai and worked as a political emissary between his home country and the West, according to reports, but it would be another 20 years…around 1860, before Japanese immigrants really began coming to the United States. At that point, groups of  Japanese immigrants began arriving in the Hawaiian Islands. The Japanese immigrants were hired to help keep the production of the plantations fluid and progressive. These immigrants worked mainly in the sugarcane fields or with pineapple production. Many of these immigrants later relocated to areas of California, Washington, and Oregon. These people did not come over as slaves, but were rather, hired to work these fields.

Japanese immigrants began arriving in the Hawaiian Islands. The Japanese immigrants were hired to help keep the production of the plantations fluid and progressive. These immigrants worked mainly in the sugarcane fields or with pineapple production. Many of these immigrants later relocated to areas of California, Washington, and Oregon. These people did not come over as slaves, but were rather, hired to work these fields.

Things really picked up after 1886, and between then and 1911, over 400,000 Japanese men and women immigrated to America…mostly to Hawaii and the West Coast. Unfortunately, as was the case with the Chinese immigration movement, the Japan immigration movement brought with it a heightened level of agitation with people living in the United States. The new immigrants were viewed as interlopers, taking the jobs of the citizens, and so they were. As a result, in 1907 there was an agreement between the nation of Japan and the  United States to have Japan stop issuing worker’s passports to come into the United States. Of course, immigration was not completely stopped. There were exceptions, like the exceptions for Japanese immigration for the spouses of those who were already working in the United States, and a select group of individuals who were requested to move to America. However, in 1924 a formal act called the Immigration Act of 1924 helped to tighten the banning of individuals. Nevertheless, it is Manjiro who is credited with getting the whole Japanese immigration started, and in 1992, he was commemorated for his early arrival when Congress dedicated the month of May as Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

United States to have Japan stop issuing worker’s passports to come into the United States. Of course, immigration was not completely stopped. There were exceptions, like the exceptions for Japanese immigration for the spouses of those who were already working in the United States, and a select group of individuals who were requested to move to America. However, in 1924 a formal act called the Immigration Act of 1924 helped to tighten the banning of individuals. Nevertheless, it is Manjiro who is credited with getting the whole Japanese immigration started, and in 1992, he was commemorated for his early arrival when Congress dedicated the month of May as Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

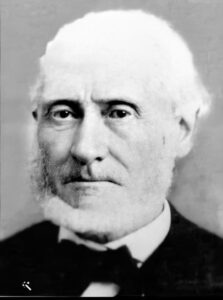

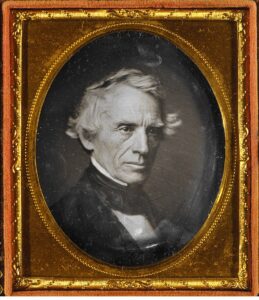

Samuel Finley Breese Morse was born on April 27, 1791, in Charlestown, Massachusetts, the first child of the pastor Jedidiah Morse (1761–1826), who was also a geographer, and his wife Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese (1766–1828). Samuel Morse was an American inventor and painter, having established his reputation as a portrait painter, but it was his work following his first wife’s death that would make his name a household word. Morse married Lucretia Pickering Walker on September 29, 1818, in Concord, New Hampshire. The couple had three children. Susan was born in 1819, Charles was born in 1823, and James was born in 1825. Shortly after giving birth to James, she died of a heart attack on February 7, 1825.

Samuel Finley Breese Morse was born on April 27, 1791, in Charlestown, Massachusetts, the first child of the pastor Jedidiah Morse (1761–1826), who was also a geographer, and his wife Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese (1766–1828). Samuel Morse was an American inventor and painter, having established his reputation as a portrait painter, but it was his work following his first wife’s death that would make his name a household word. Morse married Lucretia Pickering Walker on September 29, 1818, in Concord, New Hampshire. The couple had three children. Susan was born in 1819, Charles was born in 1823, and James was born in 1825. Shortly after giving birth to James, she died of a heart attack on February 7, 1825.

Samuel Morse was away from home, working, when he received a few letters from  his wife, Lucretia. The first letter told him that his wife was ill and the next day, while he was packing to leave, another letter arrived, informing him that she had died. Morse rushed home, but upon his arrival, was informed that she had already been buried. It was devastating, and Morse was greatly upset with the delay in his messages. He was determined to find a better way to transmit messages. Of course, nothing could be done to change the tragic loss of Lucretia, but Morse was determined to make sure this wouldn’t happen to anyone else.

his wife, Lucretia. The first letter told him that his wife was ill and the next day, while he was packing to leave, another letter arrived, informing him that she had died. Morse rushed home, but upon his arrival, was informed that she had already been buried. It was devastating, and Morse was greatly upset with the delay in his messages. He was determined to find a better way to transmit messages. Of course, nothing could be done to change the tragic loss of Lucretia, but Morse was determined to make sure this wouldn’t happen to anyone else.

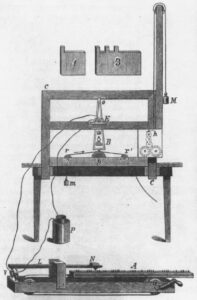

Following Lucretia’s death, Morse developed Morse code and helped to develop the commercial use of telegraphy in 1833. He also contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph system based on European telegraphs. By creating the  telegraph and drafting a series of dots and dashes to communicate via copper wires, 13 years after his wife died, Morse and co-developer, Charles Thomas Jackson successfully created a faster way of communicating and called it Morse Code.

telegraph and drafting a series of dots and dashes to communicate via copper wires, 13 years after his wife died, Morse and co-developer, Charles Thomas Jackson successfully created a faster way of communicating and called it Morse Code.

While Morse code was, without doubt his most important contribution to technology, his life didn’t end there. Morse did eventually find happiness again. He married his second wife, Sarah Elizabeth Griswold on August 10, 1848, in Utica, New York. The couple had four children, Samuel was born 1849, Cornelia was born in 1851, William was born in 1853, and Edward was born in 1857. Samuel Morse died in New York City on April 2, 1872. He was interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. By the time of his death, his estate was valued at some $500,000, which would equal about $10.8 million today.

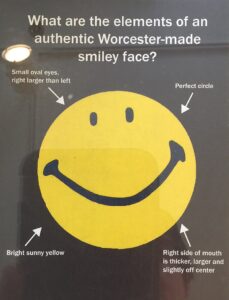

Harvey Ball was a commercial artist from Worcester, Massachusetts. You may not know him, but everyone knows what he created…the smiley face. Harvey Ross Ball was born on July 10, 1921 the third of six children to Ernest G Ball and Christine “Kitty” Ross Ball. Ball’s artistic skills presented early. As a student at Worcester South High School, he decided to become an apprentice to a local sign painter. Later he attended the Worcester Art Museum School, where he studied fine arts, however, it was not in the fine arts that Ball’s fame emerged. He is recognized as the designer of a popular smiley graphic picture, which became an enduring and notable international icon.

Harvey Ball was a commercial artist from Worcester, Massachusetts. You may not know him, but everyone knows what he created…the smiley face. Harvey Ross Ball was born on July 10, 1921 the third of six children to Ernest G Ball and Christine “Kitty” Ross Ball. Ball’s artistic skills presented early. As a student at Worcester South High School, he decided to become an apprentice to a local sign painter. Later he attended the Worcester Art Museum School, where he studied fine arts, however, it was not in the fine arts that Ball’s fame emerged. He is recognized as the designer of a popular smiley graphic picture, which became an enduring and notable international icon.

Ball worked for a local advertising firm after World War II. Then he decided to start his own business, which he called Harvey Ball Advertising, in 1959. He designed the smiley in 1963. The State Mutual Life Assurance Company of Worcester, Massachusetts, now known Hanover Insurance, had purchased Guarantee Mutual Company of Ohio. After the merger, employee morale was pretty  low. The company decided to try to boost morale, so they asked Ball to come up with an image that would help. What he created was a smiley face, with one eye bigger than the other. The creation took Ball ten minutes, and the executives liked it immediately. They paid Ball a mere $45 for his creation.

low. The company decided to try to boost morale, so they asked Ball to come up with an image that would help. What he created was a smiley face, with one eye bigger than the other. The creation took Ball ten minutes, and the executives liked it immediately. They paid Ball a mere $45 for his creation.

The smiley face became part of the company’s friendship campaign, and State Mutual handed out 100 smiley pins to employees. The aim was to get employees to smile while using the phone and doing other tasks. The buttons became popular, with orders being taken in lots of 10,000. More than 50 million smiley face buttons had been sold by 1971, and the smiley has been described as an international icon. As for Ball, well…he never applied for a trademark or copyright of the smiley and that $45 was all he ever got for his trouble. I don’t suppose that did much for his morale. Nevertheless, State Mutual didn’t make any money from the design either. According to Ball’s son, Charles, his father never regretted not registering the copyright. Charles Ball said, “he was not a money-driven guy, he used to say, ‘Hey, I can only eat one steak at a time, drive one car at a time.'”

Ball had a heart for children, and founded the World Smile Foundation in 1999, a non-profit charitable trust that supports children’s causes. Then, he came up with World Smile Day. It was a great idea, I think. How nice it is to celebrate a day dedicated to putting a smile on your face and sharing that great smile with others. The first World Smile Day was celebrated in 1999. It’s been held annually on the first Friday of October since then. After Harvey died in 2001, the “Harvey Ball World Smile Foundation” was created to honor his name and memory. The slogan of the Smile Foundation is “improving this world, one smile at a time.” The Foundation continues to be the official sponsor of World Smile Day each year. We should all consider that slogan.

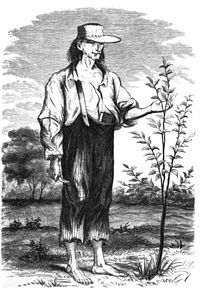

On September 26, 1774, a man named John Chapman, who is my 6th cousin 6 times removed, was born in Leominster, Massachusetts. John was the second child, after his sister Elizabeth, of Nathaniel and Elizabeth Chapman. While Nathaniel was in military service, his wife died on July 18, 1776, shortly after giving birth to a second son, Nathaniel. The baby died about two weeks after his mother. Nathaniel Chapman ended his military service and returned home in 1780 to Longmeadow, Massachusetts. In the summer of 1780 he married Lucy Cooley of Longmeadow, Massachusetts, and they had 10 children. So in the end, John Chapman came from a large family. You might wonder what all this has to do with anything, and I suppose you would be justified in asking, but I think when you hear John Chapman’s nickname, you might know who I am talking about. For most of his life, John Chapman was called, Johnny Appleseed. Most people will remember him from the history books, as an American pioneer nurseryman who introduced apple trees to large parts of Pennsylvania, Ontario, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, as well as the northern counties of present-day West Virginia. He became an American legend while he was still alive, due to his kind, generous ways, his leadership in conservation, and the symbolic importance he attributed to apples. These days plant nurseries are often named after Johnny Appleseed, including on in my city of Casper, Wyoming.

On September 26, 1774, a man named John Chapman, who is my 6th cousin 6 times removed, was born in Leominster, Massachusetts. John was the second child, after his sister Elizabeth, of Nathaniel and Elizabeth Chapman. While Nathaniel was in military service, his wife died on July 18, 1776, shortly after giving birth to a second son, Nathaniel. The baby died about two weeks after his mother. Nathaniel Chapman ended his military service and returned home in 1780 to Longmeadow, Massachusetts. In the summer of 1780 he married Lucy Cooley of Longmeadow, Massachusetts, and they had 10 children. So in the end, John Chapman came from a large family. You might wonder what all this has to do with anything, and I suppose you would be justified in asking, but I think when you hear John Chapman’s nickname, you might know who I am talking about. For most of his life, John Chapman was called, Johnny Appleseed. Most people will remember him from the history books, as an American pioneer nurseryman who introduced apple trees to large parts of Pennsylvania, Ontario, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, as well as the northern counties of present-day West Virginia. He became an American legend while he was still alive, due to his kind, generous ways, his leadership in conservation, and the symbolic importance he attributed to apples. These days plant nurseries are often named after Johnny Appleseed, including on in my city of Casper, Wyoming.

According to some accounts, an 18 year old John persuaded his 11 year old half-brother Nathaniel to go west with him in 1792. The boys lived a nomadic life until their father brought his large family west in 1805 and met  up with them in Ohio. Nathaniel decided to stay and help their father farm the land. A short time later, John began his apprenticeship as an orchardist under a Mr. Crawford, who had apple orchards, and so began his life’s journey of planting apple trees. There are stories of Johnny Appleseed practicing his nurseryman craft in the area of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and of picking seeds from the pomace at Potomac cider mills in the late 1790s. Another story has Chapman living in Pittsburgh on Grant’s Hill in 1794 at the time of the Whiskey Rebellion.

up with them in Ohio. Nathaniel decided to stay and help their father farm the land. A short time later, John began his apprenticeship as an orchardist under a Mr. Crawford, who had apple orchards, and so began his life’s journey of planting apple trees. There are stories of Johnny Appleseed practicing his nurseryman craft in the area of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and of picking seeds from the pomace at Potomac cider mills in the late 1790s. Another story has Chapman living in Pittsburgh on Grant’s Hill in 1794 at the time of the Whiskey Rebellion.

The most popular image is of Johnny Appleseed spreading apple seeds randomly everywhere he went. In reality, he planted nurseries rather than orchards, and then built fences around them to protect them from livestock. Then he left the nurseries in the care of a neighbor who sold trees on shares, and returned every year or two to tend the nursery. His first nursery was planted on the bank of Brokenstraw Creek, south of Warren, Pennsylvania. Next, he seems to have moved to Venango County along the shore of French Creek, but many of his nurseries were in the Mohican area of north-central Ohio. This area included the towns of Mansfield, Lisbon, Lucas, Perrysville, and Loudonville.

Johnny Appleseed was a bit of a missionary too. He would tell stories to children and spread The New Church gospel to the adults, receiving a floor to sleep on for the night, and sometimes supper, in return. “We can hear him read now, just as he did that summer day, when we were busy quilting upstairs, and he lay near the door,  his voice rising denunciatory and thrillin—strong and loud as the roar of wind and waves, then soft and soothing as the balmy airs that quivered the morning-glory leaves about his gray beard. His was a strange eloquence at times, and he was undoubtedly a man of genius,” reported a lady who knew him in his later years. He made several trips back east, both to visit his sister and to replenish his supply of Swedenborgian literature. Swedenborgian was also known as Swedenborgianism and the General Church of the New Jerusalem. Several historically related Christian denominations were developed as a new religious movement, by the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. Johnny preached the gospel as he traveled, and converted many Native Americans. The Native Americans regarded him as someone who had been touched by the Great Spirit, and even hostile tribes left him strictly alone. Johnny passed away about 1845, with several dates being given. I guess no one really knew the date for sure. I think my cousin might have been a very interesting man.

his voice rising denunciatory and thrillin—strong and loud as the roar of wind and waves, then soft and soothing as the balmy airs that quivered the morning-glory leaves about his gray beard. His was a strange eloquence at times, and he was undoubtedly a man of genius,” reported a lady who knew him in his later years. He made several trips back east, both to visit his sister and to replenish his supply of Swedenborgian literature. Swedenborgian was also known as Swedenborgianism and the General Church of the New Jerusalem. Several historically related Christian denominations were developed as a new religious movement, by the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. Johnny preached the gospel as he traveled, and converted many Native Americans. The Native Americans regarded him as someone who had been touched by the Great Spirit, and even hostile tribes left him strictly alone. Johnny passed away about 1845, with several dates being given. I guess no one really knew the date for sure. I think my cousin might have been a very interesting man.