maryland

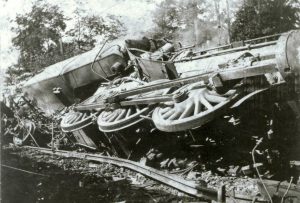

When a train derails, you know that there is going to be a big mess, and loss of life, or at the very least, injuries. And you would probably be right, but it would be a whole different situation, if multiple trains collided with each other. That is the exact scenario on January 17, 1929, in Aberdeen, Maryland, when two Pennsylvania Railroad passenger trains and a freight train all collided. While the collision was horrific, the loss of life was amazingly less that expected.

When a train derails, you know that there is going to be a big mess, and loss of life, or at the very least, injuries. And you would probably be right, but it would be a whole different situation, if multiple trains collided with each other. That is the exact scenario on January 17, 1929, in Aberdeen, Maryland, when two Pennsylvania Railroad passenger trains and a freight train all collided. While the collision was horrific, the loss of life was amazingly less that expected.

On that day, passenger train Number 412, bound from Washington to Philadelphia, struck the freight train, who was also northbound, just after it pulled from a siding, by Short Lane station, near Aberdeen. The freight cars toppled onto the southbound track, directly in front of express train Number 121, from New York to Washington. There was simply not time to avoid the disaster. The wreck killed four trainmen and seriously injured another. Conductors of the two passenger trains declared none of their passengers were seriously hurt. Brakeman, K. A. Klein, on the freight train, and flagman, V. W. Stewart, were both killed in the first crash; and engineer of the southbound express train, A. C. Terhune, and M. Goldstein, his fireman, were killed when their train ploughed into the wreckage.

Bodies of the two from the freight crew and of the passenger firemen were removed and taken to a morgue in Aberdeen, but the body of the express engineer was still under the engine five hours after the wreck. The workmen were prevented from recovering it by outpouring steam. Leon Sweeting, engineer of the northbound passenger train, was badly scalded and was taken to the Havre de Grace Hospital, where his condition was reported to be serious. John H. Lee, fireman on the same train, was in the hospital, suffering from shock.

It is thought that heavy fog in the area, prevented the engineer of northbound number 412 from seeing the tail-light of the freight train right in front of him. Some passengers on the northbound and southbound trains were said to have been slightly injured, but none was reported in serious condition. The triple crash tore up about 150 yards of track and uprooted signal and telegraph poles. Trains had to be re-routed over the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad tracks, while relief trains were sent from Baltimore to Aberdeen. While this was not the worst wreck, in fatalities and injuries, I don’t recall too many, if any others involving three trains, and the experience must have been terrifying.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian road was necessary to connect this young country. In 1806 Congress authorized construction of the road and President Jefferson signed the act establishing the National Road. It would connect Cumberland, Maryland to the Ohio River. Construction on the road, known in many places as Route 40, and in others as the Cumberland Road, began in 1811 and continued until 1834. It was designed to reach the western settlements, and was the first federally funded road in United States history.

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed that a trans-Appalachian road was necessary to connect this young country. In 1806 Congress authorized construction of the road and President Jefferson signed the act establishing the National Road. It would connect Cumberland, Maryland to the Ohio River. Construction on the road, known in many places as Route 40, and in others as the Cumberland Road, began in 1811 and continued until 1834. It was designed to reach the western settlements, and was the first federally funded road in United States history.

The first contract was awarded in 1811, and included the first 10 miles of road. These days that seems like such a short distance, but in the early 1800s, I’m sure it was considered a big job. By 1818 the road was completed to Wheeling, West Virginia. It was at this point that mail coaches began using the road. By the 1830s the federal government turned over part of the road’s maintenance responsibility to the states through which it ran. In order to help pay for the road’s upkeep, tollgates and tollhouses were built by the states. As work on the road progressed a settlement pattern developed that is still visible. Original towns and villages that were found along the National Road, remain barely touched by the passing of time. The road, also called the Cumberland Road, National Pike and other names, became Main Street in these early settlements, earning the nickname “The Main Street of America.” The height of the National Road’s popularity came in 1825 when it was celebrated in song, story, painting and poetry, but hard times hit in 1834, and construction on the road was tabled. During the 1840s popularity soared again. Travelers and drovers, westward bound, crowded the inns and taverns along the route. Huge Conestoga wagons hauled produce from farms on the frontier to the East Coast, and then returned with staples such as coffee and sugar for the western settlements. Thousands of people moved west in covered wagons and stagecoaches that traveled the road keeping to regular schedules.

In the 1870s, however, the railroads came and some of the excitement of the national road faded. In 1912 the road became part of the National Old Trails Road and its popularity returned in the 1920s with the automobile. Federal Aid became available for improvements in the road to accommodate the automobile. In 1926 the road became part of US 40 as a coast-to-coast highway. As the interstate system has grown throughout America, interest in the National Road again waned. However, now when we want to have a relaxing journey with some history thrown in, we again travel the National Road. Cameras capture old buildings, bridges and old stone mile markers. Old brick schoolhouses from early years sporadically dot the countryside and some are found in the small towns on the National Road. Many are still used, some are converted to a private residence and others stand abandoned.

Historic stone bridges dot their way along the National Road, and they have their own stories to tell. The craftsmanship of the early engineers was amazing. The S Bridge, was so named because of its design and it stands 4 miles east of Old Washington, Ohio. It was built in 1828 as part of the National Road. It is a single arch stone structure. This one of four in the state is deteriorated and is now used for only pedestrian traffic. However the owners of the bridge are attempting to obtain funding for its restoration. The stone Casselman River Bridge still stands east of Grantsville, Maryland. It is a product of the early 19th century federal government improvements program along the National Road, the Casselman River Bridge was constructed in 1813-1814. Its 80-foot span, is the largest of its type in America, and it connected Cumberland to the Ohio River. In 1933 a new steel bridge joined the banks of the Casselman River. The old stone bridge, partially restored by the State of Maryland in the 1950s is now the center of Casselman River Bridge State Park. Mile markers have been used in Europe for more than 2,000 years and our European ancestors continued that tradition here in America. These markers tell travelers how far they are from their destination and were an important icon in early National Road travel. Kids ask what they are fr, and adults nostalgically seek them out for photographing. A drive through National Road towns usually reveals one of these markers, such as the one standing by the historic Red Brick Tavern in Lafayette, Ohio.

In the 1960s Interstate 70, bypassed Route 40 and much of the National Road, leaving many businesses by the wayside. People were looking for faster cars and quicker arrival times. Life runs at a much faster pace these

days. These old roads are a great way to relax, take your time and see some sights. Traveling the National Road, you can see the timeless little villages with small restaurants where you can get a home cooked meal and a trip back in time. The Interstate often parallels the National Road, but we leave behind the old inns and farmhouses in our rush to arrive about destination.

days. These old roads are a great way to relax, take your time and see some sights. Traveling the National Road, you can see the timeless little villages with small restaurants where you can get a home cooked meal and a trip back in time. The Interstate often parallels the National Road, but we leave behind the old inns and farmhouses in our rush to arrive about destination.

After serving in the Navy for six years, my nephew, Allen Beach decided that it was time to move on to get the education that he wanted, which is hospital administration. He began his Navy career planning to become a pilot, but an injury forced him out of the program early on. He then decided to become a Corpsman, and found that he had a knack for that. His first duty station was in Bethesda, Maryland at Walter Reed Rational Military Medical Center, a term of service he was very proud of. While there, he was one of the EMTs who took care of the medical needs of the first family.

After serving in the Navy for six years, my nephew, Allen Beach decided that it was time to move on to get the education that he wanted, which is hospital administration. He began his Navy career planning to become a pilot, but an injury forced him out of the program early on. He then decided to become a Corpsman, and found that he had a knack for that. His first duty station was in Bethesda, Maryland at Walter Reed Rational Military Medical Center, a term of service he was very proud of. While there, he was one of the EMTs who took care of the medical needs of the first family.

After his term at Walter Reed Medical Center, Allen was stationed in Japan, which is where he met his future wife, Gabby, who was also a Corpsman stationed at the same base. Needless to say, Allen was very happy with his time in Japan, and meeting the love of his life. After that, Allen left the Navy, and for Gabby’s final year, they were stationed back at Walter Reed Medical Center. Now that both of them are out of the Navy, they have decided to move to Casper, Wyoming so that Gabby can continue her education too. Casper College has an excellent nursing program, and that is her chosen field. So, upon their release from the Navy, the headed west.

At this point, Allen and Gabby are living in an apartment on his mom and step-dad’s land outside of town. I’m sure that is quite a culture shock to them after the hustle and bustle of the Washington DC area. In addition,  they are getting used to the winters in Wyoming. Not that they never got snow in Japan or in Washington DC, but I don’t think they had the winds like we have here. One nice thing about the move was the ability to be closer to family. Allen and Gabby were able to spend Christmas week in Rawlins with the family there, and they all had a great time. They have really taken to country living, and other than the severe cold causing their pipes to freeze, life is good. Allen is still looking for a job, so once he gets a job they will be set, as his classes are online. We are very proud of all of his s accomplishments, and we know that the future will be bright for both of them. Today is Allen’s birthday. Happy birthday Allen!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

they are getting used to the winters in Wyoming. Not that they never got snow in Japan or in Washington DC, but I don’t think they had the winds like we have here. One nice thing about the move was the ability to be closer to family. Allen and Gabby were able to spend Christmas week in Rawlins with the family there, and they all had a great time. They have really taken to country living, and other than the severe cold causing their pipes to freeze, life is good. Allen is still looking for a job, so once he gets a job they will be set, as his classes are online. We are very proud of all of his s accomplishments, and we know that the future will be bright for both of them. Today is Allen’s birthday. Happy birthday Allen!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

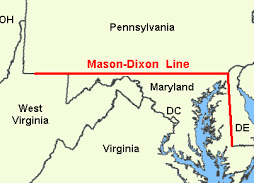

I think most of us have heard of the Mason-Dixon Line, but do we really know what it is and how it came to be called that? Maybe not. It was on October 18, 1767 that two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon completed their survey of the boundary between the colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland, as well as areas that would eventually become the states of Delaware and West Virginia. The Penn and Calvert families had hired Mason and Dixon, two English surveyors, to settle their dispute over the boundary between their two proprietary colonies, Pennsylvania and Maryland. The dispute between the families often resulted in violence between the colonies’ settlers, the British crown demanded that the parties involved hold to an agreement reached in 1732. In 1760, as part of Maryland and Pennsylvania’s adherence to this royal command, Mason and Dixon were asked to determine the exact whereabouts of the boundary between the two colonies. Though both colonies claimed the area between the 39th and 40th parallel, what is now referred to as the Mason-Dixon line finally settled the boundary at a northern latitude of 39 degrees and 43 minutes. The line was marked using stones, with Pennsylvania’s crest on one side and Maryland’s on the other.

I think most of us have heard of the Mason-Dixon Line, but do we really know what it is and how it came to be called that? Maybe not. It was on October 18, 1767 that two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon completed their survey of the boundary between the colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland, as well as areas that would eventually become the states of Delaware and West Virginia. The Penn and Calvert families had hired Mason and Dixon, two English surveyors, to settle their dispute over the boundary between their two proprietary colonies, Pennsylvania and Maryland. The dispute between the families often resulted in violence between the colonies’ settlers, the British crown demanded that the parties involved hold to an agreement reached in 1732. In 1760, as part of Maryland and Pennsylvania’s adherence to this royal command, Mason and Dixon were asked to determine the exact whereabouts of the boundary between the two colonies. Though both colonies claimed the area between the 39th and 40th parallel, what is now referred to as the Mason-Dixon line finally settled the boundary at a northern latitude of 39 degrees and 43 minutes. The line was marked using stones, with Pennsylvania’s crest on one side and Maryland’s on the other.

When Mason and Dixon began their endeavor in 1763, colonists were protesting the Proclamation of 1763, which was intended to prevent colonists from settling beyond the Appalachians and angering Native Americans. In reality, expansion was inevitable, but many in government couldn’t seem to see that. As the Mason and Dixon concluded their survey in 1767, the colonies were engaged in a dispute with the Parliament over the Townshend Acts, which were designed to raise revenue for the British empire by taxing common imports including tea. A protest that resulted in the Boston Tea Party, but that is another story. Twenty years later, in late 1700s, the states south of the Mason-Dixon line would begin arguing for the perpetuation of slavery in the new United States while those north of line hoped to phase out the ownership of human property. This period, which historians consider the era of “The New Republic,” drew to a close with the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which accepted the states south of the line as slave-holding and those north of the line as free. The compromise, along with those that followed it, eventually failed, and slavery was forbidden with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862.

One hundred years after Mason and Dixon began their effort to chart the boundary, soldiers from opposite

sides of the line spilled their blood on the fields of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the Souths final and fatal attempt to breach the Mason-Dixon line during the Civil War. One hundred and one years after the Mason and Dixon completed their line, the United States finally admitted men of any complexion born within the nation to the rights of citizenship with the ratification of the 14th Amendment…a poorly thought out amendment which continues to cause illegal immigration to this day, due to birth right citizenship.

sides of the line spilled their blood on the fields of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the Souths final and fatal attempt to breach the Mason-Dixon line during the Civil War. One hundred and one years after the Mason and Dixon completed their line, the United States finally admitted men of any complexion born within the nation to the rights of citizenship with the ratification of the 14th Amendment…a poorly thought out amendment which continues to cause illegal immigration to this day, due to birth right citizenship.

Most people know what the United States Capitol building looks like, and many have seen it, and even been inside it, but I wonder how many people know that is almost wasn’t completed. Yes, you heard me right. I almost wasn’t completed. As a young nation, the United States had no permanent capitol, and Congress met in eight different cities, including Baltimore, New York and Philadelphia, before 1791. In 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which gave President Washington the power to select a permanent home for the federal government. The following year, he chose what would become the District of Columbia from land that had been provided by Maryland. Washington picked three commissioners to oversee the capital city’s development and they in turn chose French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant to come up with the design. However, L’Enfant clashed with the commissioners and was fired in 1792. A design competition was held, and a Scotsman named William Thornton submitted the winning entry.

Most people know what the United States Capitol building looks like, and many have seen it, and even been inside it, but I wonder how many people know that is almost wasn’t completed. Yes, you heard me right. I almost wasn’t completed. As a young nation, the United States had no permanent capitol, and Congress met in eight different cities, including Baltimore, New York and Philadelphia, before 1791. In 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which gave President Washington the power to select a permanent home for the federal government. The following year, he chose what would become the District of Columbia from land that had been provided by Maryland. Washington picked three commissioners to oversee the capital city’s development and they in turn chose French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant to come up with the design. However, L’Enfant clashed with the commissioners and was fired in 1792. A design competition was held, and a Scotsman named William Thornton submitted the winning entry.

Then, on this day, September 18, 1793, Washington laid the Capitol’s cornerstone and the lengthy construction process, which would involve a line of project managers and architects, got under way. One would think that is due time, the capitol building would be finished, but in reality, it took almost a century to finish…almost 100 years!! During those years, architects came and went, the British set it on fire, and it was called into use during the Civil War. In 1800, Congress moved into the Capitol’s north wing. In 1807, the House of Representatives moved into the building’s south wing, which was finally finished in 1811. During the War of 1812, the British invaded Washington DC. They set fire to the Capitol on August 24, 1814. Thankfully, a rainstorm saved the building from total destruction. Congress met in nearby temporary quarters from 1815 to 1819. In the early 1850s, work began to expand the Capitol to accommodate the growing number of Congressmen. The Civil War halted construction in 1861 while the Capitol was used by Union troops as a hospital and barracks. Following the war, expansions and modern upgrades to the building continued into the next century.

Today, the Capitol building, with its famous cast-iron dome and important collection of American art, is part of the Capitol Complex, which includes six Congressional office buildings and three Library of Congress buildings, all developed in the 19th and 20th centuries. The Capitol, which is visited by 3 million to 5 million people each

year, has 540 rooms and covers a ground area of about four acres. I’m sure that those who visit the United States Capitol Building probably hear all about it strange past and its construction history, but maybe not. I suppose that it depends on what the tour guide finds interesting. Personally, I like the unusual construction. Thankfully, the United States Capitol did finally get built and has become the beautiful building we know today.

year, has 540 rooms and covers a ground area of about four acres. I’m sure that those who visit the United States Capitol Building probably hear all about it strange past and its construction history, but maybe not. I suppose that it depends on what the tour guide finds interesting. Personally, I like the unusual construction. Thankfully, the United States Capitol did finally get built and has become the beautiful building we know today.

Have you ever wondered how the Interstate road system got started? People didn’t just wake up one day and envision a great system of roads that could transport us from one side of the country to the other. There had to be some reasons to do such a thing, right? Well, there was. In 1919, Dwight Eisenhower was feeling a bit disenchanted with life, because his wife and infant son were living 1,500 miles away in Denver, while he was a 28 year old lieutenant colonel stationed at Maryland’s Camp Meade. He was bored and miserable, and so he and his fellow soldiers wasted the hours playing bridge and complaining about being kept stateside during World War I. What do people do when they need to break through the boredom…what else, a road trip!!

Have you ever wondered how the Interstate road system got started? People didn’t just wake up one day and envision a great system of roads that could transport us from one side of the country to the other. There had to be some reasons to do such a thing, right? Well, there was. In 1919, Dwight Eisenhower was feeling a bit disenchanted with life, because his wife and infant son were living 1,500 miles away in Denver, while he was a 28 year old lieutenant colonel stationed at Maryland’s Camp Meade. He was bored and miserable, and so he and his fellow soldiers wasted the hours playing bridge and complaining about being kept stateside during World War I. What do people do when they need to break through the boredom…what else, a road trip!!

Eisenhower heard that two volunteer tank officers from Camp Meade were needed to participate in a coast to coast military convoy to San Francisco. It was the perfect adventure, so Eisenhower immediately volunteered his services. Granted, it wasn’t the thrill of battle that the young soldier had planned to spend his time in the service engaging in, but it was far better than playing bridge. Little did he know just how grueling the trip would be. Remember that these were the early years of the automobile, and drivers were just as likely to encounter roads to nowhere, as they were the open road. Highways were not usually paved. Dirt roads could be a muddy mess or so dry that they were either dust clouds or full of ruts. Sixty miles an hour was unheard of and many roads could only be driven at the pace of a brisk walk. As a means of transporting military equipment quickly from one coast to the other…this system left much to be desired, in fact it was a miserable excuse for a road system at all. Something had to change.

Fast forward a few years…37 years to be exact, and you will find then President Dwight D Eisenhower signing the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 privately, without ceremony, on June 29, 1956. The system would take decades to build, and in reality is always under construction. The project was the largest public works project in American history. The project would pour billions of dollars into the nation’s economy all over the country, putting many people to work. Today, it continues to be a boon to the economy because of the maintenance and repairs needed to keep it going.

In 1990, as a tribute to Eisenhower, on the centennial of his birth, President George H W Bush redesignated the

interstate system as the Dwight D Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. Interstate 80, would be quite familiar to Eisenhower. It starts just across the Hudson River from New York City, then goes through New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and into Ohio, where it follows generally the route of the 1919 Army convoy to San Francisco that had sparked Eisenhower’s interest in such a system in the first place.

interstate system as the Dwight D Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. Interstate 80, would be quite familiar to Eisenhower. It starts just across the Hudson River from New York City, then goes through New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and into Ohio, where it follows generally the route of the 1919 Army convoy to San Francisco that had sparked Eisenhower’s interest in such a system in the first place.

During the years that my nephew, Allen was growing up, he and his family lived far enough away from us that we didn’t get to see them often, so my memories of those years are limited. He was named after his grandfather, my dad. Dad only had daughters and Caryl wanted to give him a namesake, so Allen became that namesake in that his first and middle name are the same as my dad’s first and last names. One thing I remember about those early years is that he had a funny way of saying Bob. He pronounced it with a long “o” sound, and it was just so cute. It always made me laugh, and for a long time I called my husband Bob with a long “o” sound. Allen seems to have a way of being funny without even trying. That really is a good trait. If we can find the humor in things, we are a blessing to those around us, and to our own spirit.

During the years that my nephew, Allen was growing up, he and his family lived far enough away from us that we didn’t get to see them often, so my memories of those years are limited. He was named after his grandfather, my dad. Dad only had daughters and Caryl wanted to give him a namesake, so Allen became that namesake in that his first and middle name are the same as my dad’s first and last names. One thing I remember about those early years is that he had a funny way of saying Bob. He pronounced it with a long “o” sound, and it was just so cute. It always made me laugh, and for a long time I called my husband Bob with a long “o” sound. Allen seems to have a way of being funny without even trying. That really is a good trait. If we can find the humor in things, we are a blessing to those around us, and to our own spirit.

After Allen graduated from high school, he moved to Casper and started college here, but he wasn’t sure what he wanted to do with his life at that point, so he made the decision to follow in his dad’s footsteps and join the Navy, planning to go in to become a pilot. He was doing well in that field, when a foot injury sidelined him for long enough that he had to change course again.

It is in his new field, that I believe Allen has found his true calling. Allen was accepted in the program to become a Hospitalman, or HN. He studied very hard and finished first in his class. In fact, he graduated with the highest scores to come through the corps school in 5 years. With that ranking and his grades, Allen was offered a very distinguished position. He is stationed at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, which is a coveted post in itself, but his duties go further than that. Allen is proud to assist in the care of the President of the United States and his family whenever they come in for check ups, shots, or any other kind of medical care. It is a position that is only offered to the cream of the crop, so we are very proud indeed. This does not exempt him from doing the normal ship duty that is a part of the Navy, and so there are several other people who share that position and take turns doing ship duty, but the job is his when he is on shore duty.

Allen will also have the opportunity to continue his education, and should he choose to, could even become a doctor. The doors are wide open for him. I don’t know if he plans to make a career of the Navy or not. I don’t think that is a decision he has made yet, but we are all very proud of his accomplishments so far, and I know that he will do very well in whatever he decides to do with his future. Love you Allen.