lakota sioux

Valentine Trant O’Connell McGillycuddy was born on February 14, 1849 in Racine, Wisconsin to Irish immigrants Daniel McGillycuddy (1821–1892), a merchant, and Joana (Trant) McGillycuddy (1813–1892). His brother, Francis was 6 years older than he was. The McGillycuddy family moved to Detroit when Valentine was 13. At 20 years of age, McGillycuddy graduated from the Detroit Medical School. He began working as a doctor at the Wayne County Insane Asylum and practiced medicine for one year, a job that nearly drove him crazy…literally. Next, he began teaching at the medical college. His longstanding love for the outdoors eventually led McGillycuddy to leave the city medical field. At the request of Army engineer, General Cyrus Comstock, McGillycuddy surveyed and mapped the Great Lakes and Chicago’s devastation after the Great Fire. He probably could have stayed and continued working for the Army in the Great Lakes area, but his heart was in the West.

Valentine Trant O’Connell McGillycuddy was born on February 14, 1849 in Racine, Wisconsin to Irish immigrants Daniel McGillycuddy (1821–1892), a merchant, and Joana (Trant) McGillycuddy (1813–1892). His brother, Francis was 6 years older than he was. The McGillycuddy family moved to Detroit when Valentine was 13. At 20 years of age, McGillycuddy graduated from the Detroit Medical School. He began working as a doctor at the Wayne County Insane Asylum and practiced medicine for one year, a job that nearly drove him crazy…literally. Next, he began teaching at the medical college. His longstanding love for the outdoors eventually led McGillycuddy to leave the city medical field. At the request of Army engineer, General Cyrus Comstock, McGillycuddy surveyed and mapped the Great Lakes and Chicago’s devastation after the Great Fire. He probably could have stayed and continued working for the Army in the Great Lakes area, but his heart was in the West.

In 1875 he joined the US Geological Survey sponsored Newton-Jenney Expedition to the Black Hills. This trip would set the course for the rest of his life. Part scientific exploration, part treasure hunt, the expedition was fueled by the trip George Armstrong Custer made into the land of the Lakota and the reports of gold he brought back. Following that trip, McGillycuddy was appointed as the Army surgeon at Nebraska’s Fort Robinson and later administrator at Nebraska’s Red Cloud Agency in 1877. That appointment led to a friendship with Crazy Horse, and antipathy toward Red Cloud, both powerful leaders of the Dakota plains.

McGillycuddy had an uncanny knack for being at the right place at the right time, which put him right in the middle of things during the most consequential era of the American frontier. He met, treated, befriended, or opposed some of its most iconic figures including Little Big Horn principals, George Armstrong Custer, General George Crook, and Major Mark Reno, as well as Buffalo Bill Cody, Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane Canary, the legendary Sioux chiefs Sitting Bull and American Horse, and John Wesley Powell…the man who mapped the Grand Canyon.

It also placed him squarely in the middle of a deadly struggle between the young upstart, Crazy Horse and the dominant chief of the Oglala Lakota, Red Cloud. The two were on different sides of just about everything. Crazy Horse resisted Anglo-American incursion at every turn, taking part in nearly every important battle including the Little Big Horn and the subsequent Dakota War. Red Cloud, who signed the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie, was deeply disappointed in the outcome. After having his own war named for him, Red Cloud’s War of 1866, he was finally willing to go along to get along. He and his band settled on the reservation, where he squabbled with Dr John J Saville, the government’s agency man.

McGillycuddy was at Fort Robinson when Crazy Horse surrendered in 1877. The move may have partially been prompted by his wife’s illness. McGillycuddy successfully treated Black Shawl. Some say she had tuberculosis and others claim it was cholera, which killed her three-year-old daughter. Whatever her ailment, saving her life brought about a close bond between Crazy Horse and the doctor. Six months after he surrendered, Crazy Horse was dead. Many people think he was assassinated, stirring a controversy that remains unresolved to this day. McGillycuddy spent the the wounded Crazy Horse’s last hours at his bedside. Varying accounts of the incident were provided by eye witnesses. Army Private William Gentles, an Irish immigrant soldier with a sketchy military career is a prime candidate for the killing of Crazy Horse, stabbing him with a bayonet. The Army’s retelling has Crazy Horse challenging the guards with two concealed knives as they attempted to lock him up, however. In the struggle, he fell on his own weapon. This version was attributed to Charging Bear, the real life “Little Big Man.” He is depicted as either a Crazy Horse lieutenant and “Shirt Wearer,” or a jealous rival who sought to curry favor with his Army captors. A number of Lakota genealogists lean heavily toward the latter, describing him as manipulative. He received a medal for his involvement in the incident.

McGillycuddy certified that his friend, Crazy Horse died near midnight on September 5, 1877, saying his killing “absolutely inexcusable.” Little Big Man was just part of the conspiracy. Crazy Horse was surrounded by shadowy characters. French and Lakota translator, William Garnett, thought that Little Big Man was the killer, but more than a dozen witnesses say an Army guard, perhaps Gentles, stabbed Crazy Horse. In the aftermath, Garnett was labeled a spy. Supposedly Garnett had no connection to Red Cloud, but Nellie Larrabee did. It was speculated that perhaps married to Crazy Horse, Larrabee, known as Chi Chi and Brown Eyed Woman, was sent to the Crazy Horse, Black Shawl household by Red Cloud. It was thought that she was there to act as a spy. Red Cloud was definitely not a fan of Crazy Horse. He thought his resistance to US forces was detrimental to the Lakota cause, but Red Cloud may have also been jealous of the attention the Army gave him. And then things got complicated. Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, a relative of Black Shawl, joined forces against the government’s attempts to seize tribal lands. Spotted Tail approved the Fort Laramie Treaty but continued to fight for sovereignty when the terms of the treaty were not met. Like Red Cloud, he believed it was a fool’s errand to oppose the government on the battlefield.

Along with Garnett, many Lakota deeply mistrusted Larrabee, calling her an “evil woman,” who helped lead Crazy Horse into a “domestic trap” that eventually caused his downfall and placed Spotted Tail in a Red Cloud conspiracy, as well. Others say Spotted Tail was unaware of any plot against Crazy Horse. After Crazy Horse died, McGillycuddy was named the Indian Agent on the Pine Ridge. His old enemy, Red Cloud had a hand to his downfall, accusing him of mismanagement and wrongdoing. A number of investigations were launched into the claims. Still McGillycuddy did his job, and amid charges of “tyranny” and fraud, he established a reservation police force and a boarding school. The breaking point came when the doctor was ordered to fire an otherwise blameless clerk. Rather than do so, he resigned his position in October of 1882 and moved with his wife Frances “Fanny” (Hoyt) McGillycuddy to Rapid City.

It was the end of an era. McGillycuddy served as Dean of the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology and was appointed South Dakota’s first State Surgeon. He was elected Rapid City mayor in 1897, but when Fanny died, he moved to California. Later, he married Julia Blanchard and enlisted at the start of World War I, serving Alaska and the western states during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. His nemesis, Red Cloud, the last and one of the best known Lakota leaders, outlived nearly all of them. He died on the Pine Ridge Reservation, December 10, 1909 at 87 after converting to Christianity. He claimed the government had made many promises, but kept only one, saying, “They promised to take our land…and they took it.” There are 128 known photographs of Red Cloud, none of Crazy Horse, save a latter-day image found in a derelict photo studio in Chadron, Nebraska. It is still unverified. Black Shawl died in 1927, presumably of influenza. Helen “Nellie” Larrabee is believed to have died in about 1880. One source lists her burial in Charles Mix County near the present day Lake Andes, South Dakota.

Valentine McGillycuddy died on June 6, 1939, at the age of 90. Flags were lowered to half staff on the Pine Ridge at the news of his passing and his ashes were interred on Black Elk Peak in the Black Hills. Formerly known as Harney Peak, he had scaled the mountain as a young surveyor with the Newton-Jenney expedition. A simple stone monument reads “Valentine T. McGillycuddy, Wasicu Wakan, (Holy White Man) 1849-1939.”

Valentine McGillycuddy’s grave site, Custer State Park, South Dakota, is accessible only by hiking trails, the most commonly used is Trail No. 9, from the Sylvan Lake Day Use Area. It is a site my husband, Bob and I have visited 15 times over the years. The three-mile hike through the ponderosa pine leads to the former fire tower atop what is now Black Elk Peak.

Valentine McGillycuddy’s grave site, Custer State Park, South Dakota, is accessible only by hiking trails, the most commonly used is Trail No. 9, from the Sylvan Lake Day Use Area. It is a site my husband, Bob and I have visited 15 times over the years. The three-mile hike through the ponderosa pine leads to the former fire tower atop what is now Black Elk Peak.

Anyone who has spent much time in the Black Hills has most likely seen Deadwood, and knows it to be a historic gambling town where many famous Wild West characters hung out and died. Legends like Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane each left their mark. Hickok, a legendary man even in his own lifetime, was shot in the back of the head by Jack McCall, while playing poker at the No. 10 Saloon on August 2, 1876. Calamity Jane was renowned for her excellent marksmanship, as well as her preference for men’s clothing, and brash behavior.

Anyone who has spent much time in the Black Hills has most likely seen Deadwood, and knows it to be a historic gambling town where many famous Wild West characters hung out and died. Legends like Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane each left their mark. Hickok, a legendary man even in his own lifetime, was shot in the back of the head by Jack McCall, while playing poker at the No. 10 Saloon on August 2, 1876. Calamity Jane was renowned for her excellent marksmanship, as well as her preference for men’s clothing, and brash behavior.

Deadwood also had, in addition to its tough individuals, others such as Reverend Henry W. Smith. Preacher Smith was the first Methodist minister to come to the Black Hills. Smith was mysteriously murdered on Sunday, August 20, 1876, while walking to Crook City to deliver a sermon. These individuals are just a few of the many notables buried in Mount Moriah Cemetary, which was established in 1877 or 1878.

That’s all well known to many people, but some may not know that the settlement of Deadwood began illegally in the 1870s on land which had been granted to the Native Americans. In 1874, Colonel George Armstrong Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills and announced the discovery of gold on French Creek near what is now Custer, South Dakota. That announcement ushered in the Black Hills Gold Rush and gave rise to the new and lawless town of Deadwood. In 1875, a miner named John Pearson found gold in a narrow canyon in the Northern Black Hills. This canyon became known as “Deadwood Gulch,” because of the many dead trees that lined the canyon walls at that time. The name stuck. Try as they might, the government couldn’t keep the situation under wraps, in order to honor the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which forever ceded the Black Hills to the Lakota-Sioux. The government dispatched several military units to forts in the surrounding area to keep people from entering the Hills. However, people illegally entered the area anyway, searching for gold or adventure. Despite the efforts of the military and federal government. They were driven by dreams and greed.

Once Deadwood was established, the mining camp was quickly swarming with thousands of prospectors searching for an easy way to get rich. Fred and Moses Manuel, claimed the Homestake Mine, which proved to be the most profitable in the area. Although the Manuels had been lucky, others were not so fortunate. Most of the early population was in Deadwood to mine for gold, but the lawless town naturally attracted a crowd of rough and shady characters too. These particular individuals made the early days of Deadwood rough and wild.  A mostly male population eagerly patronized the many saloons, gambling establishments, dance halls, and brothels. These establishments were considered legitimate businesses and were well known throughout the area.

A mostly male population eagerly patronized the many saloons, gambling establishments, dance halls, and brothels. These establishments were considered legitimate businesses and were well known throughout the area.

In 1890, the railroad connected the town to the outside world. Illegal beginnings aside, Deadwood was a town that was now here to stay. The treaty with the Lakota-Sioux was broken and the Black Hills would never again belong to them. As unfair as it was to break the treaty, I don’t think that it could have lasted forever anyway, because the United Stated was going to be populated from coast to coast one way or the other.

Most people have heard of Crazy Horse, the Lakota Sioux Indian who has been memorialized in the Black Hills. Most of us know that Crazy Horse was a great warrior, but I did not know much about his upbringing. Crazy Horse was born on the Republican River about 1845. Crazy Horse was an uncommonly handsome man, and a man of refinement and grace. He was as modest and courteous as Chief Joseph, but unlike Chief Joseph, Crazy Horse was a born warrior, but a gentle warrior, a true brave, who stood for the highest ideal of the Lakota Sioux people. Of course, you would never hear these things from his enemies, but history should probably judge him more by the accounts of those who knew him…his own people.

Most people have heard of Crazy Horse, the Lakota Sioux Indian who has been memorialized in the Black Hills. Most of us know that Crazy Horse was a great warrior, but I did not know much about his upbringing. Crazy Horse was born on the Republican River about 1845. Crazy Horse was an uncommonly handsome man, and a man of refinement and grace. He was as modest and courteous as Chief Joseph, but unlike Chief Joseph, Crazy Horse was a born warrior, but a gentle warrior, a true brave, who stood for the highest ideal of the Lakota Sioux people. Of course, you would never hear these things from his enemies, but history should probably judge him more by the accounts of those who knew him…his own people.

No matter what Crazy Horse the man was or was thought to be, Crazy Horse, the boy showed great bravery a number of times. In those days, the Sioux prided themselves on the training and development of their sons and daughters, and not a step in that development was overlooked as an excuse to bring the child before the public by giving a feast in its honor. At such times the parents often gave so generously to the needy that they almost impoverished themselves, thus setting an example to the child of self-denial for the general good. His first step alone, the first word spoken, first game killed, the attainment of manhood or womanhood, each was the occasion of a feast and dance in his honor, at which the poor always benefited to the full extent of the parents’ ability. He was carefully brought up according to the tribal customs. I suppose it would have put him in the Indian version of today’s high society.

He was about five years old when the tribe was snowed in one severe winter. They were very short of food, but his father tirelessly hunted for food. The buffalo, their main dependence, were not to be found, but he was out in the storm and cold every day and finally brought in two antelopes. Young Crazy Horse got on his pet pony and rode through the camp, telling the old folks to come to his mother’s teepee for meat. Neither his father nor mother had authorized him to do this, and before they knew it, old men and women were lined up before the teepee home, to receive the meat, in answer to his invitation. As a result, the mother had to distribute nearly all of it, keeping only enough for two meals. On the following day he asked for food. His mother told him that the old folks had taken it all, and added: “Remember, my son, they went home singing praises in your name, not my name or your father’s. You must be brave. You must live up to your reputation.” And so he did.

When he was about twelve he went to look for the ponies with his little brother, whom he loved much, and took a great deal of pains to teach what he had already learned. They came to some wild cherry trees full of ripe fruit. Suddenly, the brothers were startled by the growl and sudden rush of a bear. Young Crazy Horse pushed his brother up into the nearest tree and then jumped upon the back of one of the horses, which was frightened and ran some distance before he could control him. As soon as he could, he turned him about and came back, yelling and swinging his lariat over his head. The bear at first showed fight but finally turned and ran. The old man who told me this story added that young as he was, he had some power, so that even a grizzly did not care to tackle him. I believe it is a fact that a grizzly will dare anything except a bell or a lasso line, so he accidentally hit upon the very thing which would drive him off.

At this period of his life, as was customary with the best young men, he spent much time in prayer and solitude. Just what happened in these days of his fasting in the wilderness and upon the crown of bald buttes, no one will ever know. These things may only be known when one has lived through the battles of life to an honored old age. He was much sought after by his youthful associates, but was noticeably reserved and modest. Yet, in the moment of danger he at once rose above them all…a natural leader! Crazy Horse was a typical Sioux brave, and from the point of view of the white man, an ideal hero.

At the age of sixteen he joined a war party against the Gros Ventres. He was well in the front of the charge,  and at once established his bravery by following closely one of the foremost Sioux warriors, by the name of Hump, drawing the enemy’s fire and circling around their advance guard. Suddenly Hump’s horse was shot from under him, and there was a rush of warriors to kill or capture him while he was down. Amidst a shower of arrows Crazy Horse jumped from his pony, helped his friend into his own saddle, sprang up behind him, and carried him off to safety, although they were hotly pursued by the enemy. Thus, in his first battle he associated himself with the wizard of Indian warfare, and Hump, who was then at the height of his own career. Hump pronounced Crazy Horse the coming warrior of the Teton Sioux. He was killed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in 1877, so that he lived barely thirty-three years.

and at once established his bravery by following closely one of the foremost Sioux warriors, by the name of Hump, drawing the enemy’s fire and circling around their advance guard. Suddenly Hump’s horse was shot from under him, and there was a rush of warriors to kill or capture him while he was down. Amidst a shower of arrows Crazy Horse jumped from his pony, helped his friend into his own saddle, sprang up behind him, and carried him off to safety, although they were hotly pursued by the enemy. Thus, in his first battle he associated himself with the wizard of Indian warfare, and Hump, who was then at the height of his own career. Hump pronounced Crazy Horse the coming warrior of the Teton Sioux. He was killed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in 1877, so that he lived barely thirty-three years.

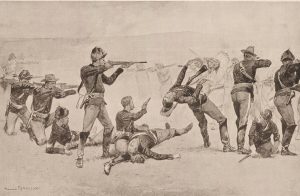

Who shot first? We will never know, but on December 29, 1890, that first shot started a massacre. What lead up to that fateful day? For all of his 27 years, Black Elk’s had watched as the way of life of the Lakota Sioux on the Great Plains was taken away. Black Elk was a medicine man, who witnessed years of broken treaties. He watched as the white men “came in like a river” when gold was discovered in the Dakota Territory’s Black Hills in 1874. He was there two years later when Custer and his men were annihilated at Little Big Horn. He saw the Lakota’s traditional hunting grounds evaporate as white men decimated the native buffalo population. The Lakota, who once roamed as free as the bison on the Great Plains, were now mostly confined to government reservations.

Who shot first? We will never know, but on December 29, 1890, that first shot started a massacre. What lead up to that fateful day? For all of his 27 years, Black Elk’s had watched as the way of life of the Lakota Sioux on the Great Plains was taken away. Black Elk was a medicine man, who witnessed years of broken treaties. He watched as the white men “came in like a river” when gold was discovered in the Dakota Territory’s Black Hills in 1874. He was there two years later when Custer and his men were annihilated at Little Big Horn. He saw the Lakota’s traditional hunting grounds evaporate as white men decimated the native buffalo population. The Lakota, who once roamed as free as the bison on the Great Plains, were now mostly confined to government reservations.

Life for the Sioux was very bleak during the winter of 1890. Then came a glimmer of hope with the new Ghost Dance spiritual movement, which preached that Native Americans had been confined to reservations because they had angered the gods by abandoning their traditional customs. Leaders promised that the buffalo would return, relatives would be resurrected and the white man would be cast away if the Native Americans performed a ritual “ghost dance.” Such a ritual was seriously scary for the “white man.” The settlers grew increasingly alarmed and worried that an uprising was coming. “Indians are dancing in the snow and are wild and crazy,” telegrammed a frightened government agent stationed on South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation to the commissioner of Indian affairs on November 15, 1890. “We need protection and we need it now.”

General Nelson Miles arrived with 5,000 troops as part of the Seventh Cavalry, which was Custer’s old command. He ordered the arrest of several Sioux leaders. When Indian police tried to arrest Chief Sitting Bull, who was mistakenly believed to have been joining the Ghost Dancers, the noted Sioux leader was killed in the melee. Then, on December 28, the cavalry caught up with Chief Big Foot, who was leading a band of upwards of 350 people to join Chief Red Cloud, near the banks of Wounded Knee Creek. The American forces arrested Big Foot, who was too ill with pneumonia to sit up, let alone walk, and positioned their Hotchkiss guns on a rise overlooking the Lakota camp. As a bugle blared the following morning, December 29, American soldiers mounted their horses and surrounded the Native American camp. A medicine man who started to perform the ghost dance cried out, “Do not fear but let your hearts be strong. Many soldiers are about us and have many bullets, but I am assured their bullets cannot penetrate us.” He implored the heavens to scatter the soldiers like the dust he threw into the air.

The cavalry went teepee to teepee seizing axes, rifles and other weapons. As the soldiers attempted to confiscate a weapon they spotted under the blanket of a deaf man, who could not hear their orders, a gunshot suddenly rang out. It was not clear which side shot first, but within seconds the American soldiers launched a hail of bullets from rifles, revolvers and rapid-fire Hotchkiss guns into the teepees. Outnumbered and

outgunned, the Lakota offered meek resistance. Big Foot was shot where he lay on the ground. Boys who had been happily playing leapfrog were mowed down. In just a matter of minutes, at least 150 Lakota Sioux Indians were killed along with 25 American soldiers. Half the victims were women and children. The soldiers might have thought they were being attacked…it’s hard to say. Nevertheless, that first shot brought about a massacre.

outgunned, the Lakota offered meek resistance. Big Foot was shot where he lay on the ground. Boys who had been happily playing leapfrog were mowed down. In just a matter of minutes, at least 150 Lakota Sioux Indians were killed along with 25 American soldiers. Half the victims were women and children. The soldiers might have thought they were being attacked…it’s hard to say. Nevertheless, that first shot brought about a massacre.

In my many hikes to the Harney Peak lookout, I have noticed many times the marker there for Dr Valentine McGillycuddy. I suppose that the main reason it has stuck in my head is because of my grandfather, George Byer, who used to call our house and ask for Mrs McGillycuddy. We always knew it was Grandpa, but we went along with the joke anyway. Of course, Grandpa’s Mrs McGillycuddy was fictional, while Valentine McGillycuddy was a real person. I did some research a few years ago, and found out that Valentine McGillycuddy was the first white man to climb all the way to the top of Harney Peak. Many have followed in his footsteps, myself and my husband included. Harney Peak, so named in the late 1850s by Lieutenant Gouverneur K. Warren in honor of General William S. Harney, who was commander of the military in the Black Hills area. The Lakota Sioux Indians called it Hinhan Kaga, which means “Making of Owls” in English. I think I like that name.

In my many hikes to the Harney Peak lookout, I have noticed many times the marker there for Dr Valentine McGillycuddy. I suppose that the main reason it has stuck in my head is because of my grandfather, George Byer, who used to call our house and ask for Mrs McGillycuddy. We always knew it was Grandpa, but we went along with the joke anyway. Of course, Grandpa’s Mrs McGillycuddy was fictional, while Valentine McGillycuddy was a real person. I did some research a few years ago, and found out that Valentine McGillycuddy was the first white man to climb all the way to the top of Harney Peak. Many have followed in his footsteps, myself and my husband included. Harney Peak, so named in the late 1850s by Lieutenant Gouverneur K. Warren in honor of General William S. Harney, who was commander of the military in the Black Hills area. The Lakota Sioux Indians called it Hinhan Kaga, which means “Making of Owls” in English. I think I like that name.

Dr McGillycuddy first came to the Black Hills with the Jenny-Newton Party. His mission was to survey and map

the Black Hills, and to confirm that gold had been discovered there. It was during this excursion that he climbed Harney Peak. There had been other white men to climb the mountain, including General George Custer, but they all stopped just short of the peak, because it was to difficult to make it…something I think I can relate to. McGillycuddy angled a felled tree into a crevice in the granite, and made his way to the very top. I can totally feel his elation and sense of accomplishment, since I have felt the same way myself. My guess is that it would not be the last trip he made to the top either. That mountain has a way of calling you back for a second and even third or more visits.

the Black Hills, and to confirm that gold had been discovered there. It was during this excursion that he climbed Harney Peak. There had been other white men to climb the mountain, including General George Custer, but they all stopped just short of the peak, because it was to difficult to make it…something I think I can relate to. McGillycuddy angled a felled tree into a crevice in the granite, and made his way to the very top. I can totally feel his elation and sense of accomplishment, since I have felt the same way myself. My guess is that it would not be the last trip he made to the top either. That mountain has a way of calling you back for a second and even third or more visits.

McGillycuddy became a friend to Crazy Horse, and in fact was with him when he died after being stabbed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska in 1877. After that time, the Lakota Sioux named McGillycuddy Tasunka Witko Kola,  which means “Crazy Horse’s Friend” in English. Other Native Americans named McGillycuddy Wasicu Wakan, which means “Holy White Man” in English. Dr Valentine McGillycuddy did lead a very amazing life. His first wife died, and he moved to San Francisco to continue his medical practice. There he married Julia Blanchard. After he passed away in 1939, Julia wrote a book about his life called “McGillycuddy, Agent” which was how he signed his name during his favorite role in life. He was a friend to the Indians, and did his best to educate them by building a school for the children. He was a calming influence on the relationship between the Indians and the White Man. It is quite fitting then that his ashes be entombed on the mountain that he loved. It gives a totally different feeling to the little plaque that is there…if one researches it.

which means “Crazy Horse’s Friend” in English. Other Native Americans named McGillycuddy Wasicu Wakan, which means “Holy White Man” in English. Dr Valentine McGillycuddy did lead a very amazing life. His first wife died, and he moved to San Francisco to continue his medical practice. There he married Julia Blanchard. After he passed away in 1939, Julia wrote a book about his life called “McGillycuddy, Agent” which was how he signed his name during his favorite role in life. He was a friend to the Indians, and did his best to educate them by building a school for the children. He was a calming influence on the relationship between the Indians and the White Man. It is quite fitting then that his ashes be entombed on the mountain that he loved. It gives a totally different feeling to the little plaque that is there…if one researches it.

For most of his life in the United States, my great grandfather, Cornelius Byer, was friends with the Indians. He and my grandfather, George Byer were invited to Pow Wows with the Indians, and many of them came to their home bearing gifts and just to visit. That wasn’t the normal course of events in those days, however. For many of the people that the Indians dubbed, The White Man, crossing paths with the Indians meant death. Many of the Indians were considered criminals. They were locked away in prison or, if they were lucky, the reservations. The reservations weren’t great, but they were better than prisons…I suppose.

For most of his life in the United States, my great grandfather, Cornelius Byer, was friends with the Indians. He and my grandfather, George Byer were invited to Pow Wows with the Indians, and many of them came to their home bearing gifts and just to visit. That wasn’t the normal course of events in those days, however. For many of the people that the Indians dubbed, The White Man, crossing paths with the Indians meant death. Many of the Indians were considered criminals. They were locked away in prison or, if they were lucky, the reservations. The reservations weren’t great, but they were better than prisons…I suppose.

Crazy Horse has a serious score to settle with The White Man. The government wasn’t suppose to let the settlers into the Dakotas. Then explorers went in anyway, and found gold. Of course, the government reneged on the deal, and The White Man came flooding into the Dakotas. In reality, it was going to be inevitable. A some point, the United States and her people were going to grow to a place whereby they would need more room. Eventually someone was bound to find the Dakotas, and especially one of my favorite places, The Black Hills. This was the area of the United States where the Lakota Sioux and Crazy Horse lived.

The breaking of the treaty to keep the Dakota Territory in the hands of the Lakota Sioux brought the government into a war with the Lakota Sioux and with Crazy Horse. Crazy Horse would lead the Lakota Sioux to victory in The Battle of the Little Big Horn. After that battle, Crazy Horse was a wanted man, and the cavalry would stop at nothing to find him. After the Battle of the Little Big Horn, on June 25, 1876, it was inevitable that Crazy Horse would one day have to surrender. That day came on May 6, 1877, when Crazy Horse, He Dog, Little Big Man, Iron Crow, and several others surrendered themselves to First Lieutenant William P Clark. For the next four months Crazy Horse resided in his village near the Red Cloud Agency, but Red Cloud and Spotted  Tail became jealous of the attention the Army gave to Crazy Horse. They had adopted many of the White Man’s ways, and when they heard a rumor that Crazy Horse was planning to slip away, and go back to their old ways. Crazy Horse had actually agreed to fight on the side of the White Man, but his words were misinterpreted, and on the morning of September 4, 1877, just four months after his surrender, the Army attacked Crazy Horse’s village. Crazy Horse agreed to accompany Lieutenant Jesse Lee back to Fort Robinson, there Lieutenant Lee was told to turn him over to the Officer of the Day. He didn’t want to, but he did. As he was taken into custody, Crazy Horse struggles and was stabbed with a bayonet by one of the members of the guard. He died later that night. It was a sad case of misunderstanding, and it cost him his life.

Tail became jealous of the attention the Army gave to Crazy Horse. They had adopted many of the White Man’s ways, and when they heard a rumor that Crazy Horse was planning to slip away, and go back to their old ways. Crazy Horse had actually agreed to fight on the side of the White Man, but his words were misinterpreted, and on the morning of September 4, 1877, just four months after his surrender, the Army attacked Crazy Horse’s village. Crazy Horse agreed to accompany Lieutenant Jesse Lee back to Fort Robinson, there Lieutenant Lee was told to turn him over to the Officer of the Day. He didn’t want to, but he did. As he was taken into custody, Crazy Horse struggles and was stabbed with a bayonet by one of the members of the guard. He died later that night. It was a sad case of misunderstanding, and it cost him his life.

Most of us are able to trace our roots back to the Old West, since many of our ancestors were homesteaders. The Old West was a dangerous place to live. There were few, if any lawmen around, and outlaws found it to be a good hiding place. Probably a bigger concern for many of the settlers was the Indian population. There were a lot of hard feelings toward the white man, because of broken treaties and stolen lands. Still, this wasn’t really the fault of the settlers and homesteaders, but they were the ones who often suffered the consequences. For this reason, friendships between the Indians and the White Man were rare.

Most of us are able to trace our roots back to the Old West, since many of our ancestors were homesteaders. The Old West was a dangerous place to live. There were few, if any lawmen around, and outlaws found it to be a good hiding place. Probably a bigger concern for many of the settlers was the Indian population. There were a lot of hard feelings toward the white man, because of broken treaties and stolen lands. Still, this wasn’t really the fault of the settlers and homesteaders, but they were the ones who often suffered the consequences. For this reason, friendships between the Indians and the White Man were rare.

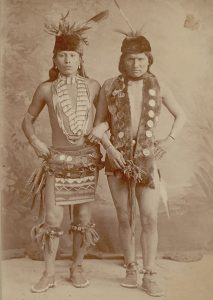

My grandfather’s family was privileged to have one of those rare relationships. They were accepted and even loved by the Indians in the area. They were invited to the Pow Wows and other celebrations. The had meals and probably hunts with the Indians, and got to know them well. They knew men like Chief Thin Elk and Sitting Bull, two Lakota Sioux Indians and their tribes. They spent time with them, and learned their customs…spoke their language. Not many White Men had the opportunity to do that.

Of course, when we think back on the Old West, the first thing that comes to mind are the old shows, like Bonanza, Gunsmoke, and Little House on the Prairie.

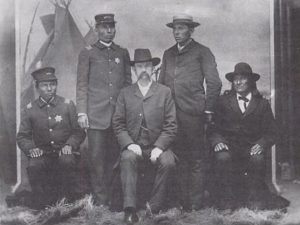

We seldom think of the real people who lived those times…especially our own ancestors. I had been told that my great grandfather knew some Indians, but it just didn’t register until I saw pictures of him with the Indians…being friends with the Indians…having Pow Wows with the Indians. My great grandfather was one of those rare people who really did know Indians from the Old West. It was such an eye opening moment for me.

We seldom think of the real people who lived those times…especially our own ancestors. I had been told that my great grandfather knew some Indians, but it just didn’t register until I saw pictures of him with the Indians…being friends with the Indians…having Pow Wows with the Indians. My great grandfather was one of those rare people who really did know Indians from the Old West. It was such an eye opening moment for me.