general

There have been many firsts that our United States Presidents have been able to celebrate. One such first was “the first president to ride in a helicopter.” That particular first honor went to a well-known general turned president…Dwight D Eisenhower. On July 12, 1957, President Eisenhower became that first United States president to fly in a helicopter when a United States Air Force H-13J-BF Sioux, serial number 57-2729 (c/n 1576). The helicopter was piloted by Major Joseph E Barrett, USAF. It departed the White House lawn for Camp David, the presidential retreat in the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland. Of course, no presidential trip happens without a Secret Service agent, also on board. On that same day, a second H-13J, 57-2728 (c/n 1575), followed the first, this one carrying President Eisenhower’s personal physician and a second Secret Service agent.

There have been many firsts that our United States Presidents have been able to celebrate. One such first was “the first president to ride in a helicopter.” That particular first honor went to a well-known general turned president…Dwight D Eisenhower. On July 12, 1957, President Eisenhower became that first United States president to fly in a helicopter when a United States Air Force H-13J-BF Sioux, serial number 57-2729 (c/n 1576). The helicopter was piloted by Major Joseph E Barrett, USAF. It departed the White House lawn for Camp David, the presidential retreat in the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland. Of course, no presidential trip happens without a Secret Service agent, also on board. On that same day, a second H-13J, 57-2728 (c/n 1575), followed the first, this one carrying President Eisenhower’s personal physician and a second Secret Service agent.

While that first flight was really a pleasure ride, the main purpose of the helicopter was to rapidly move the  president from the White House to Andrews Air Force Base where his Lockheed VC-121E Constellation, Columbine III, would be standing by. This was intended to be a way of escape to Andrews or to other secure facilities in case of an emergency. Major Barrett was selected as the pilot because of his extensive experience as a combat pilot. They needed someone who was a capable pilot under pressure, a skill that Major Barrett proved he possessed during World War II, when he flew the B-17 Flying Fortress four-engine heavy bomber. Major Barrett was credited with carrying out a helicopter rescue 70 miles behind enemy lines during the Korean War. For his heroics, he was awarded the Silver Star.

president from the White House to Andrews Air Force Base where his Lockheed VC-121E Constellation, Columbine III, would be standing by. This was intended to be a way of escape to Andrews or to other secure facilities in case of an emergency. Major Barrett was selected as the pilot because of his extensive experience as a combat pilot. They needed someone who was a capable pilot under pressure, a skill that Major Barrett proved he possessed during World War II, when he flew the B-17 Flying Fortress four-engine heavy bomber. Major Barrett was credited with carrying out a helicopter rescue 70 miles behind enemy lines during the Korean War. For his heroics, he was awarded the Silver Star.

Not only was the helicopter a great way to quickly secure the president, but that original pilot was the perfect person to make sure that the president was safely transferred to that secure location. The President of the United States is always in a degree of danger. It goes with the territory I suppose. It is the job of his security details is to make sure that no threats are ever able to be carried out. They are very loyal and would die to protect the president.

The Bell Helicopter Company of Fort Worth, Texas, manufactured two of the helicopters. They were delivered to the Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base on March 29, 1957. The two presidential H-13Js were nearly identical to the commercial Bell Model 47J Ranger. They were capable of carrying a pilot and up to three passengers. An enclosed cabin was built on a tubular steel framework with all-metal semi-monocoque tail boom. The main rotor was 37 feet 2 inches in diameter and tail rotor was 5 feet 10.13 inches, making the helicopter an overall length of 43 feet 3¾ inches with rotors turning. It stood 9 feet 8 inches and weighed 2,800 pounds.

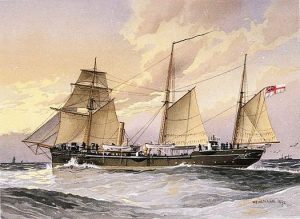

Some wars can last for years and years, while others are relatively short lived, but no war, at least to date, has been as short as the Anglo-Zanzibar War that was fought on August 27, 1896. The war was so short, that it is estimated to have lasted between 38 and 40 minutes…yes, I said minutes. The cause of the war was the sudden and unexplained death of pro-British Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini, followed by the subsequent succession of Sultan Khalid bin Barghash, who was suspected of killing his uncle in order to take over. The British authorities preferred Hamud bin Muhammed, who was well known for his favorable stance toward British interests. A treaty signed in 1886, called for any candidate for accession to the sultanate, to be approved by the British consul, and Khalid had not fulfilled this requirement. The British considered this an act of war and sent an ultimatum to Khalid demanding that he order his forces to stand down and leave the palace. In response, Khalid called up his palace guard and barricaded himself inside the palace.

Some wars can last for years and years, while others are relatively short lived, but no war, at least to date, has been as short as the Anglo-Zanzibar War that was fought on August 27, 1896. The war was so short, that it is estimated to have lasted between 38 and 40 minutes…yes, I said minutes. The cause of the war was the sudden and unexplained death of pro-British Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini, followed by the subsequent succession of Sultan Khalid bin Barghash, who was suspected of killing his uncle in order to take over. The British authorities preferred Hamud bin Muhammed, who was well known for his favorable stance toward British interests. A treaty signed in 1886, called for any candidate for accession to the sultanate, to be approved by the British consul, and Khalid had not fulfilled this requirement. The British considered this an act of war and sent an ultimatum to Khalid demanding that he order his forces to stand down and leave the palace. In response, Khalid called up his palace guard and barricaded himself inside the palace.

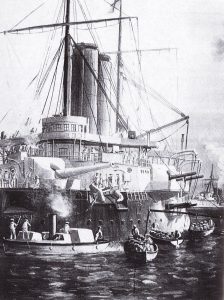

At 9:00am East Africa Time on 27 August, the ultimatum expired. The British had gathered three cruisers, two gunboats, 150 marines and sailors, and 900 Zanzibaris in the harbor area. The Royal Navy contingent were  under the command of Rear-Admiral Harry Rawson while their Zanzibaris were commanded by Brigadier-General Lloyd Mathews of the Zanzibar army, who was also the First Minister of Zanzibar. Around 2,800 Zanzibaris defended the palace, most of whom were recruited from the civilian population, but they also included the sultan’s palace guard and several hundred of his servants and slaves. The defenders had several artillery pieces and machine guns, which were set in front of the palace sighted at the British ships. The first bombardment, launched at 9:02am quickly set the palace on fire, disabling the defending artillery. A small naval action took place in the harbor, with the British sinking the Zanzibari royal yacht HHS Glasgow and two smaller vessels. The palace fired some shots ineffectually at the pro-British Zanzibari troops as they approached the palace. The flag at the palace was shot down and fire ceased at 9:40am. It was almost a matter of ready…aim…oh, never mind.

under the command of Rear-Admiral Harry Rawson while their Zanzibaris were commanded by Brigadier-General Lloyd Mathews of the Zanzibar army, who was also the First Minister of Zanzibar. Around 2,800 Zanzibaris defended the palace, most of whom were recruited from the civilian population, but they also included the sultan’s palace guard and several hundred of his servants and slaves. The defenders had several artillery pieces and machine guns, which were set in front of the palace sighted at the British ships. The first bombardment, launched at 9:02am quickly set the palace on fire, disabling the defending artillery. A small naval action took place in the harbor, with the British sinking the Zanzibari royal yacht HHS Glasgow and two smaller vessels. The palace fired some shots ineffectually at the pro-British Zanzibari troops as they approached the palace. The flag at the palace was shot down and fire ceased at 9:40am. It was almost a matter of ready…aim…oh, never mind.

Sultan Khalid bin Barghash’s forces sustained roughly 500 casualties, while the British only had one sailor injured. Sultan Khalid immediately ran to the German consulate, where he was given asylum and then he escaped to German East Africa, located in the mainland part of present day Tanzania. The British quickly placed Sultan Hamud bin Muhammed in power at the head of a puppet government. The war marked the end of the Zanzibar Sultanate as a sovereign state and the start of a period of heavy British influence. The badly damaged palace complex was completely changed by the war. The harem, lighthouse and palace were demolished as the  bombardment had left them unsafe. The palace site was turned into an area of gardens, and a new palace was erected on the site of the harem. The House of Wonders was almost undamaged and would later become the main secretariat for the British governing authorities. During renovation work on the House of Wonders in 1897, a clock tower was added to its frontage to replace the lighthouse lost to the shelling. The wreck of the Glasgow remained in the harbor in front of the palace, where the shallow waters ensured that her masts would remain visible for several years to come, as a reminder of what would happen if the treaty was not followed. In 1912, it was finally broken up for scrap.

bombardment had left them unsafe. The palace site was turned into an area of gardens, and a new palace was erected on the site of the harem. The House of Wonders was almost undamaged and would later become the main secretariat for the British governing authorities. During renovation work on the House of Wonders in 1897, a clock tower was added to its frontage to replace the lighthouse lost to the shelling. The wreck of the Glasgow remained in the harbor in front of the palace, where the shallow waters ensured that her masts would remain visible for several years to come, as a reminder of what would happen if the treaty was not followed. In 1912, it was finally broken up for scrap.