dresden

The American prisoners of war had heard the Allied planes pass overhead many times before, but this was different. Along with the sound of the planes, came the howling of Dresden’s air raid sirens. Dresden was known as the “Florence of the Elbe.” The American prisoners of war were moved two stories below into a meat locker. I don’t really understand that in light of the outcome. The Germans didn’t care about their prisoners, but I guess they didn’t care about their own countrymen either. Why would they move their prisoners to a place of safety, but leave the people of the town to fend for themselves. I suppose that they might have wanted the prisoners for leverage, but how good is a victory, if there are no one to live in the town.

The American prisoners of war had heard the Allied planes pass overhead many times before, but this was different. Along with the sound of the planes, came the howling of Dresden’s air raid sirens. Dresden was known as the “Florence of the Elbe.” The American prisoners of war were moved two stories below into a meat locker. I don’t really understand that in light of the outcome. The Germans didn’t care about their prisoners, but I guess they didn’t care about their own countrymen either. Why would they move their prisoners to a place of safety, but leave the people of the town to fend for themselves. I suppose that they might have wanted the prisoners for leverage, but how good is a victory, if there are no one to live in the town.

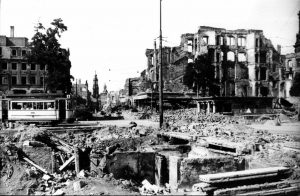

In this instance, I suppose it didn’t matter, because when the prisoners were brought back to the surface, “the city was gone”…levelled by the bombs from the RAF and the USAAF. One prisoner, Kurt Vonnegut who was a writer and social critic, recalled the scene…shocked. The devastation was unbelievable, the bombing had reduced the “Florence of the Elbe” to rubble and flames. Still, Vonnegut could not help but be thankful that he was still alive. Who wouldn’t be thankful. He was alive, and he would be forever thankful. Who wouldn’t be. It was a second chance.

The devastating, three-day Allied bombing attack on Dresden from February 13 to 15, 1945 in the final months of World War II became one of the most controversial Allied actions of the war. Some 2,700 tons of explosives and incendiaries were dropped by 800-bomber raid and decimated the German city.

Dresden was a major center for Nazi Germany’s rail and road network. The plan was to destroy the city, and thereby overwhelm German authorities and services, and clog all transportation routes with hordes of refugees. An estimated 22,700 to 25,000 people were killed, in the attacks. Normally, Dresden had 550,000 citizens, but at the time there were approximately 600,000 refugees too. The Nazis tried to say that 550,000 had been killed, but that number was quickly proven wrong.

The Allied assault came a less than a month after 19,000 US troops were killed in Germany’s last-ditch offensive at the Battle of the Bulge, and three weeks after the grim discovery of the atrocities committed by Nazi forces at Auschwitz. In an effort to force a surrender, the Dresden bombing was intended to terrorize the civilian population locally and nationwide. It certainly had that effect in 1945.

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In the summer of 1914, the Dresden was patrolling the Caribbean Sea. Its assignment was to safeguard German investments and German citizens living abroad in the region. Then, on July 20, during a bitter civil war in Mexico, the Dresden was called upon to give safe passage to Mexican president, Victoriano Huerta, by transporting him and his family as they escaped to Jamaica, where they received asylum from the British government. Then came news from Europe of Austria’s ultimatum to Serbia and the imminent possibility of war. The German’s put the fleet on alert. By the first week of August the nations of Europe were at war. The Dresden was sent to South America to attack British shipping interests there, and it sunk several merchant ships as it traveled to Cape Horn, at the southern tip of Chile. The Dresden eluded the British naval squadron in  the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

Just five weeks later, the Dresden was the only German ship to escape destruction at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on November 8, when the British light cruisers Inflexible and Invincible, commanded by Sir Doveton Sturdee, sank four of von Spee’s ships. Lost were Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Leipzig and Nurnberg. As a crew member of Dresden wrote later of watching one of the other ships sink, “Each one of us knew he would never see his comrades again, no one on board the cruiser can have had any illusions about his fate.” Then the Dresden escaped under cover of bad weather south of the Falkland Islands.

Dresden consistently avoided capture by the British navy over the next several months, while sinking a number of cargo ships and then seeking refuge in the network of channels and bays in southern Chile. In need of repairs, the Dresden put into an island off the Chilean coast, in Cumberland Bay on March 8th. Captain, Fritz Emil von Luedecke, had decided the repairs were necessary in the wake of such heavy and extended use. Captain von Luedecke sent out many messages asking for fuel in the hopes of reaching any passing coal ships in the area, but the messages were picked up the British ships, Kent and Glasgow six days later. After a  hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.

hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.