crime

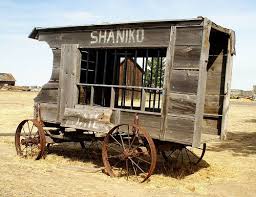

Most people know what the paddy wagon is, and nobody wants to end up in one. An old term for arresting vehicle, the term gets it’s roots from the Irish. Apparently, many of the police officers in early America were of Irish descent. According to Dictionary.com, “Irishman,” 1780, slang, from the pet form of the common Irish proper name Patrick (Irish Padraig). It was in use in black slang by 1946 for any “white person.” Paddy wagon is 1930, perhaps so called because many police officers were Irish. Paddywhack (1881) originally meant “an Irishman.” I suppose that many would look at this slang name for police officer as disrespectful, and they might be right, but no more disrespectful that pig or even cop. Nevertheless, the Paddy Wagon was just a

Most people know what the paddy wagon is, and nobody wants to end up in one. An old term for arresting vehicle, the term gets it’s roots from the Irish. Apparently, many of the police officers in early America were of Irish descent. According to Dictionary.com, “Irishman,” 1780, slang, from the pet form of the common Irish proper name Patrick (Irish Padraig). It was in use in black slang by 1946 for any “white person.” Paddy wagon is 1930, perhaps so called because many police officers were Irish. Paddywhack (1881) originally meant “an Irishman.” I suppose that many would look at this slang name for police officer as disrespectful, and they might be right, but no more disrespectful that pig or even cop. Nevertheless, the Paddy Wagon was just a  vehicle used to transport prisoners to jail. These days, unless it is a big group being arrested at one time, paddy wagons aren’t used much, but they used to be much more common. I’m sure there were many outlaws who knew the inside of a paddy wagon well…at least the ones who were’t very good at their skill. Those who were good at it usually avoided the paddy wagons.

vehicle used to transport prisoners to jail. These days, unless it is a big group being arrested at one time, paddy wagons aren’t used much, but they used to be much more common. I’m sure there were many outlaws who knew the inside of a paddy wagon well…at least the ones who were’t very good at their skill. Those who were good at it usually avoided the paddy wagons.

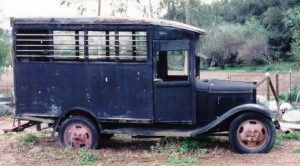

Back in the Old West, paddy wagons really were wagons, but then so was every other mode of personal transportation, and many forms of business transportation. With the invention of the motorized vehicle, came a different type of Paddy Wagon too. And with the invention of the motorcycle, came an even more unusual type of Paddy Wagon. I  can’t really imagine being taken to jail in a cage attached to a motorcycle, but there were those who were taken that way. This seemed to be common in Los Angeles, which makes sense, because many other places would be too cold for that. Still, imagine being hauled to jail in a cage for all the locals to see. No privacy there. I suppose that would be a special type of punishment for sure, the crime and the embarrassment. Or maybe criminals don’t get embarrassed. I can’t really say. All I know is that if I ever had to be hauled to jail in a Paddy Wagon, I would prefer the type we have today, with no windows.

can’t really imagine being taken to jail in a cage attached to a motorcycle, but there were those who were taken that way. This seemed to be common in Los Angeles, which makes sense, because many other places would be too cold for that. Still, imagine being hauled to jail in a cage for all the locals to see. No privacy there. I suppose that would be a special type of punishment for sure, the crime and the embarrassment. Or maybe criminals don’t get embarrassed. I can’t really say. All I know is that if I ever had to be hauled to jail in a Paddy Wagon, I would prefer the type we have today, with no windows.

The Spencer ancestry is riddled with names that have been passed down from generation to generation. So much so, in fact, that it can get confusing when researching one’s ancestry. Common names are William, Robert, Thomas, John, Allen, and Christopher. My dad’s family was no different than any other of the Spencer families. The boys in the family were William, named after his grandfather, William, who had a great grandfather named William, and many more I’m sure. My dad was Allen, who was named after his dad Allen, who was named after his grandfather Allen. And many of the children also used those same names, so there were cousins named William and Allen too. Most of the time it only created problems with the ancestry, mail, school things, and such, but when a man named Ethan Allen Spencer (relation, I’m sure, but just how I don’t know) decided that he needed a little bit of excitement in his life, he decided to go from a law-abiding farm family background to becoming a bank and train robber. Ethan Allen “Al” Spencer was born the day after Christmas in 1887 near Lenepah in Nowata County. He came from a law-abiding farm family. He married and soon was the father of a baby girl. So, why would he abandon all that to become a criminal.

The Spencer ancestry is riddled with names that have been passed down from generation to generation. So much so, in fact, that it can get confusing when researching one’s ancestry. Common names are William, Robert, Thomas, John, Allen, and Christopher. My dad’s family was no different than any other of the Spencer families. The boys in the family were William, named after his grandfather, William, who had a great grandfather named William, and many more I’m sure. My dad was Allen, who was named after his dad Allen, who was named after his grandfather Allen. And many of the children also used those same names, so there were cousins named William and Allen too. Most of the time it only created problems with the ancestry, mail, school things, and such, but when a man named Ethan Allen Spencer (relation, I’m sure, but just how I don’t know) decided that he needed a little bit of excitement in his life, he decided to go from a law-abiding farm family background to becoming a bank and train robber. Ethan Allen “Al” Spencer was born the day after Christmas in 1887 near Lenepah in Nowata County. He came from a law-abiding farm family. He married and soon was the father of a baby girl. So, why would he abandon all that to become a criminal.

“Al” Spencer became a criminal as the era of horseback riding was coming to an end, and modern motorized criminals were just getting started. That fact, made Spencer an almost forgotten outlaw. Spencer began his career in crime by getting caught stealing cattle in his early 30s. Then in 1919, he and two men burglarized a clothing store in Neodesha, Kansas. Detectives recovered most of the stolen property and arrested Spencer in La Junta, Colorado. The Kansas court convicted and sentenced him to five years in prison. Then the Oklahoma authorities gained custody of Spencer so they could try him on charges of cattle theft. Spencer pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three to 10 years in the Oklahoma penitentiary at McAlester. He began serving his sentence in March 1920. If you ask me, he should have stuck to farming, because he wasn’t very good at crime. Spencer became friends with another convict named Henry Wells and learned a great deal about crime…becoming better, I suppose…at least as long has Wells was with him. In the 1920s, it was not unusual for Oklahoma governors to grant convicts a leave of absence from prison…even some convicted of major crimes. Spencer was given leave on July 26, 1921, to attend to “some family business” supposedly. He returned to McAlester a month later and became a trustee and was trained to be an electrician. Early in 1922, he was assigned to do electrical work outside the prison in someone’s home. He completed the work, but then he packed up his tools and didn’t return to the prison.

Within a month, Spencer had hooked up with Silas Meigs, who had escaped in a similar fashion from the prison. The pair robbed the American National Bank at Pawhuska, making a “major” haul of $147. Soon the two men robbed a bank at Broken Bow, and this one netted a little more profit. They escaped with between $7,000 and $8,500. They forced a motorist to take them three miles north of town where they had left two horses. The robbers rode away. A few days later Meigs was killed in a gun battle with lawmen northwest of Bartlesville, where he had gone to visit his brother. Spencer remained hidden in the Osage Hills, a vast stretch of country with timber, rocky canyons and thickets of almost impenetrable scrub oak. Friends and relatives brought him food. Spencer later joined up with Henry Wells and two other criminals and robbed a bank at Pineville in  southwest Missouri. Spencer soon hopped a freight train bound for Oklahoma. Spencer found three other men to help him burglarize a store in Ochelata south of Bartlesville. They were surprised by the town’s night marshal who was shot and killed before the outlaws fled in a car. On June 16, Spencer and another man robbed the Elgin State Bank in Chautauqua County, Kansas. They fled with about $2,000 in cash and $20,000 in bonds.

southwest Missouri. Spencer soon hopped a freight train bound for Oklahoma. Spencer found three other men to help him burglarize a store in Ochelata south of Bartlesville. They were surprised by the town’s night marshal who was shot and killed before the outlaws fled in a car. On June 16, Spencer and another man robbed the Elgin State Bank in Chautauqua County, Kansas. They fled with about $2,000 in cash and $20,000 in bonds.

Exactly how many banks were robbed by Ethan Allen “Al” Spencer during the eighteen months following his escape is not known. Evidence suggests he probably robbed at least 20 banks in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas. The end of his crime spree came on a Saturday evening, September 15, 1923, when he was shot and killed. There is, however, debate on just how he was killed. U.S. Marshal Alva McDonald, a veteran lawman and personal friend of Teddy Roosevelt, claimed he and other lawmen shot Spencer just south of Caney, Kansas. Another account reported that Spencer was killed about five miles north of Coffeyville, Kansas. The third account came from outlaw Henry Wells’ autobiography. Wells claims that Stanley Snyder, a friend of Spencer’s, killed the outlaw with a shotgun while Spencer was eating supper. Some friend he must have been, but then I guess there is no honor among thieves. Al Spencer’s outlaw days were over, nevertheless, and a new breed of bad men soon took his place using only automobiles. Spencer was the last major Oklahoma outlaw to use horses in his crimes.

Most of the time, when we think of crime and criminals, we think of the worst evil there could be in a person, and I suppose that some criminals have more evil tendencies than others, but once in a while, someone decides to put a bit of a different twist on their crime…intending to romanticize it or give it a Robin Hood feel. In a large part, it is the media that truly romanticizes it or gives it notoriety. If the media didn’t report on every episode of the criminal’s life of crime, perhaps it would not seem so exciting to people, and maybe it wouldn’t inspire other criminals to…go for it. It all seems so exciting, at least that’s how the media plays it up.

Most of the time, when we think of crime and criminals, we think of the worst evil there could be in a person, and I suppose that some criminals have more evil tendencies than others, but once in a while, someone decides to put a bit of a different twist on their crime…intending to romanticize it or give it a Robin Hood feel. In a large part, it is the media that truly romanticizes it or gives it notoriety. If the media didn’t report on every episode of the criminal’s life of crime, perhaps it would not seem so exciting to people, and maybe it wouldn’t inspire other criminals to…go for it. It all seems so exciting, at least that’s how the media plays it up.

In reality, Bonnie and Clyde…notorious robbers and murders lived a very basic existence, and in many ways it was disgusting. Despite common popular culture depictions of Bonnie and Clyde, their life on the run was far from glamorous. They often ate sardines from the can, bathed in rivers, and drove through the night, taking shifts sleeping and driving, all in order to evade capture. They hid out in the forest, hoping not to be seen…always standing guard…always watching. Bonnie Parker met Clyde Barrow in Texas when she was 19 years old. Her husband, whom she married when she was 16, was serving time in jail for murder, and Clyde seemed exciting. Shortly after they met, Barrow was imprisoned for robbery. Bonnie visited Clyde every day, and smuggled a gun into prison to help him escape. He did escape, but was quickly recaptured in Ohio and sent back to jail. When Clyde was paroled in 1932, he immediately hooked up with Bonnie, and the couple began a life of crime together. Apparently Bonnie had a thing for bad boys…to her detriment, in the end.

The pair stole a car and committed several robberies, before Bonnie was caught by police and sent to jail for  two months. Immediately after her release in mid-1932, she hooked up with Clyde again. Over the next two years, the couple teamed with various accomplices to rob a string of banks and stores across five states…Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, New Mexico and Louisiana. To law enforcement agents, the Barrow Gang, including Clyde’s childhood friend, Raymond Hamilton, W.D. Jones, Henry Methvin, Barrow’s brother Buck and his wife Blanche, among others, were cold-blooded criminals who didn’t hesitate to kill anyone who got in their way, especially police or sheriff’s deputies. To the public, however, Bonnie and Clyde’s reputation as dangerous outlaws was mixed with a romantic view of the couple as “Robin Hood”-like folk heroes. Their fame was increased by the fact that Bonnie was a woman, which made her an unlikely criminal, and by the fact that the couple posed for playful photographs together, which were later found by police and released to the media. Police almost captured Bonnie and Clyde in the spring of 1933, with surprise raids on their hideouts in Joplin and Platte City, Missouri. Buck Barrow was killed in the second raid, and Blanche was arrested, but Bonnie and Clyde escaped once again. In January 1934, they attacked the Eastham Prison Farm in Texas to help Hamilton break out of jail, shooting several guards with machine guns…killing one.

two months. Immediately after her release in mid-1932, she hooked up with Clyde again. Over the next two years, the couple teamed with various accomplices to rob a string of banks and stores across five states…Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, New Mexico and Louisiana. To law enforcement agents, the Barrow Gang, including Clyde’s childhood friend, Raymond Hamilton, W.D. Jones, Henry Methvin, Barrow’s brother Buck and his wife Blanche, among others, were cold-blooded criminals who didn’t hesitate to kill anyone who got in their way, especially police or sheriff’s deputies. To the public, however, Bonnie and Clyde’s reputation as dangerous outlaws was mixed with a romantic view of the couple as “Robin Hood”-like folk heroes. Their fame was increased by the fact that Bonnie was a woman, which made her an unlikely criminal, and by the fact that the couple posed for playful photographs together, which were later found by police and released to the media. Police almost captured Bonnie and Clyde in the spring of 1933, with surprise raids on their hideouts in Joplin and Platte City, Missouri. Buck Barrow was killed in the second raid, and Blanche was arrested, but Bonnie and Clyde escaped once again. In January 1934, they attacked the Eastham Prison Farm in Texas to help Hamilton break out of jail, shooting several guards with machine guns…killing one.

Texan prison officials hired Captain Frank Hamer, a retired Texas police officer, as a special investigator to track down Bonnie and Clyde. After a three month search, Hamer traced the couple to Louisiana, where Henry Methvin’s family lived. Bonnie and Clyde appeared, the officers opened fire, killing the couple instantly in a hail of

bullets. All told, the Barrow Gang was believed to have been responsible for the deaths of 13 people, including nine police officers. Bonnie and Clyde are still seen by many as romantic figures, however, especially after the success of the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, starring Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty. It’s really a sad thing when crime is romanticized, because people think of it as an exciting, when in fact, it is a dead end road.

bullets. All told, the Barrow Gang was believed to have been responsible for the deaths of 13 people, including nine police officers. Bonnie and Clyde are still seen by many as romantic figures, however, especially after the success of the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, starring Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty. It’s really a sad thing when crime is romanticized, because people think of it as an exciting, when in fact, it is a dead end road.

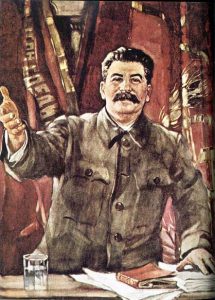

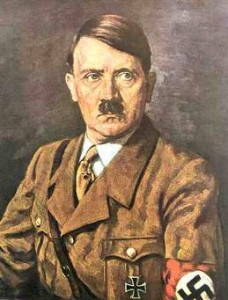

Imagine being in a country where being afraid is a crime. I’m sure you are wondering how that is possible…in any country, but I assure you, it is. That was the case on this day, July 27, 1943 in Russia. Joseph Stalin was the premier and dictator of Russia at that time in history, and Adolf Hitler was the dictator of Germany. The Germans were advancing into Russian territory, and Stalin was determined to stop them, no matter the cost.

Imagine being in a country where being afraid is a crime. I’m sure you are wondering how that is possible…in any country, but I assure you, it is. That was the case on this day, July 27, 1943 in Russia. Joseph Stalin was the premier and dictator of Russia at that time in history, and Adolf Hitler was the dictator of Germany. The Germans were advancing into Russian territory, and Stalin was determined to stop them, no matter the cost.

Hitler had become quite bold because of the early successes against Russia in his goal of taking Leningrad and Stalingrad. The attack on Stalingrad proved, however, that the Russians had superior manpower and it was an enormous drain on German resources and troop strength. The Germans were repulsed by a fierce Soviet fighting force, that had been reinforced with more men and materials. Hitler made the decision to turn his sights to Leningrad.

Stalin needed to make sure his force wouldn’t back down…no matter what happened. The motivation to stand  their ground needed to apply to both officers and civilians alike, or he was sure that Leningrad would be lost. That was when Stalin decided to put order number 227 into effect. So, what was order number 227? The order declared, “Panic makers and cowards must be liquidated on the spot. Not one step backward without orders from higher headquarters! Commanders…who abandon a position without an order from higher headquarters are traitors to the Fatherland.” Basically the order said that no one…not one person would be a coward. The order became known as the “not one step backward” order. The military personnel, as well as civilians were forced to fight for their city.

their ground needed to apply to both officers and civilians alike, or he was sure that Leningrad would be lost. That was when Stalin decided to put order number 227 into effect. So, what was order number 227? The order declared, “Panic makers and cowards must be liquidated on the spot. Not one step backward without orders from higher headquarters! Commanders…who abandon a position without an order from higher headquarters are traitors to the Fatherland.” Basically the order said that no one…not one person would be a coward. The order became known as the “not one step backward” order. The military personnel, as well as civilians were forced to fight for their city.

I think I can understand what Stalin was doing, but it seems such a drastic measure to take. Still, while some  people might fight the enemy to the end, others might decide that their city wasn’t worth their life. If the penalty for backing off was instant liquidation, then standing and fighting became the only way to have a chance at life. In my opinion, that as far as ways to gain loyalty goes, this was not the best of plans, but then forced loyalty seldom is. Still, one must never underestimate the love a patriot feels for their country. The “not one step backward” order was virtually unnecessary, in that on the day the order was issued, the Russian peasants and other supporters in the Leningrad region killed a German official, Adolf Beck, whose job was to send agricultural products from occupied Russia to Germany and to German troops. The Russian patriots also set fire to the granaries and barns in which the stash of agricultural products was stored before transport. A partisan pamphlet issued an order of its own: “Russians! Destroy the German landowners. Drive the Germans from the land of the Soviets!” I guess Stalin had misjudged his peoples’ loyalty.

people might fight the enemy to the end, others might decide that their city wasn’t worth their life. If the penalty for backing off was instant liquidation, then standing and fighting became the only way to have a chance at life. In my opinion, that as far as ways to gain loyalty goes, this was not the best of plans, but then forced loyalty seldom is. Still, one must never underestimate the love a patriot feels for their country. The “not one step backward” order was virtually unnecessary, in that on the day the order was issued, the Russian peasants and other supporters in the Leningrad region killed a German official, Adolf Beck, whose job was to send agricultural products from occupied Russia to Germany and to German troops. The Russian patriots also set fire to the granaries and barns in which the stash of agricultural products was stored before transport. A partisan pamphlet issued an order of its own: “Russians! Destroy the German landowners. Drive the Germans from the land of the Soviets!” I guess Stalin had misjudged his peoples’ loyalty.