civil war

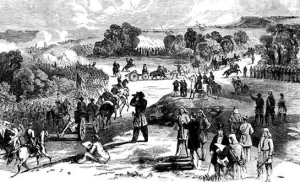

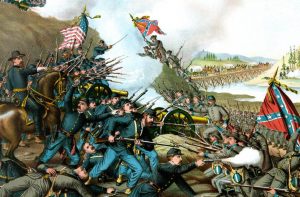

When the gunfire in a battle begins, most of us want to be as far away as possible, including the soldiers fighting in the battle, but in the case of The Battle of Bull Run during the American civil war, this was not the case. In a seriously strange phenomenon, many of Washington’s civilians and the wealthy elite, including congressmen and their families, went on picnics on the sidelines to watch the battle. After that, it became known as “The Picnic Battle” but it was definitely no picnic, as they would soon find out. What no one realized was that The Battle of Bull Run, fought on July 21, 1861, was actually going to be remembered as the first gory conflict in a long and bloody war.

When the gunfire in a battle begins, most of us want to be as far away as possible, including the soldiers fighting in the battle, but in the case of The Battle of Bull Run during the American civil war, this was not the case. In a seriously strange phenomenon, many of Washington’s civilians and the wealthy elite, including congressmen and their families, went on picnics on the sidelines to watch the battle. After that, it became known as “The Picnic Battle” but it was definitely no picnic, as they would soon find out. What no one realized was that The Battle of Bull Run, fought on July 21, 1861, was actually going to be remembered as the first gory conflict in a long and bloody war.

Bull Run was the first land battle of the Civil War. It was a battle that was fought at a time when many Americans believed the war would be short and relatively bloodless. They just really didn’t understand how this was going to play out. So, believe it or not, the civilians went out to watch the war, bringing a picnic lunch along with them. If you think about it, bringing the family and a picnic lunch out to watch a battle, had to seem strange, or even insane, and really it was, but many of the civilians were there because they had to be.

While the reporters were there too, for their own selfish reasons, they were quick to condemn the other civilians who were there, calling them frivolous. The Boston Herald published a lengthy, “not-so-funny” comedy poem about the scene. They were making the civilians look reckless. In the poem, HR Tracy describes a story “lacking in glory” about “careless picnickers who heedlessly went out to watch the battle and then ran away, driving over dead and wounded in their carriages.” This kind of public criticism gave rise to the idea of Bull Run as the “picnic battle” but there was more going on. No one really knows exactly how many civilians were there on that day. The recruits in the battle signed up to Lincoln’s army for a 90-day term, because they all thought the war would be over that fast. It’s also hard to be sure how many watchers there were. Many people say men, women and children, but others say it was mostly men.

The people did bring food and even picnic baskets to watch the battle, but it wasn’t exactly like they thought it was a leisurely day out for either spectators or combatants. Picnic food “was more of a necessity than a frivolous pursuit on a Sunday afternoon,” writes Jim Burgess writes for the Civil War Trust. Just getting to Centreville, where the battle was fought, was a seven-hour carriage ride away from Washington, so they had to take food for the journey, because the local Virginians were not going to offer the Union onlookers any kind of hospitality. Some called them a “throng of sightseers” while others mentioned that they were selling pies and other edibles. I think the whole thing was a misunderstanding of epic proportions. Unfortunately, after the  people found out how horrific the whole thing was, and began to witness the terrible bloodshed, they were also subjected to the snide remarks of the media, as if they didn’t already feel bad enough.

people found out how horrific the whole thing was, and began to witness the terrible bloodshed, they were also subjected to the snide remarks of the media, as if they didn’t already feel bad enough.

The reality was that the battle wasn’t just a spectator sport. It was important politically, so the politicians attended. It was important socially, so the journalists attended. It was also an opportunity to sell food, so the food vendors attended. In the end, it was really a circus, and once it was over, there was no one left who innocently thought that this war would end in 90 days, and no one left that thought there would be little bloodshed.

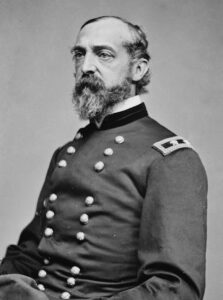

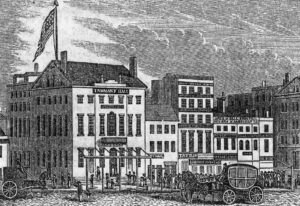

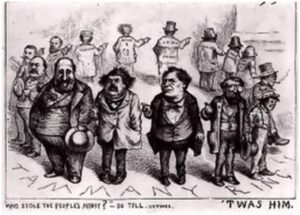

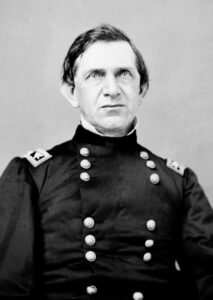

Soldiers are trained to obey orders without thought of the moral aspects the order might have carried. Nevertheless, not every order is a good one. Still, there have been a number of times when disobeying an order was very questionable, such as the order given to General Daniel Sickles at the Battle of Gettysburg. Sickles was a Tammany Hall politician with ambitions of becoming president. Tammany Hall, which was also known as the Society of Saint Tammany, the Sons of Saint Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. In New York City and New York state politics, and it had become the main local political machine of the Democratic Party. The Tammany Hall politicians focused on bringing immigrants, most notably the Irish, into American politics from the 1850s, and into the 1960s. Tammany Hall politicians virtually controlled the Democratic nominations and political patronage in Manhattan for over 100 years following the mayoral victory of Fernando Wood in 1854. These politicians used their patronage resources to build a loyal, well-rewarded core of district and precinct leaders, and after 1850, the vast majority were Irish Catholics due to mass immigration from Ireland during and after the Irish Famine of the late 1840s.

Soldiers are trained to obey orders without thought of the moral aspects the order might have carried. Nevertheless, not every order is a good one. Still, there have been a number of times when disobeying an order was very questionable, such as the order given to General Daniel Sickles at the Battle of Gettysburg. Sickles was a Tammany Hall politician with ambitions of becoming president. Tammany Hall, which was also known as the Society of Saint Tammany, the Sons of Saint Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was an American political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789, as the Tammany Society. In New York City and New York state politics, and it had become the main local political machine of the Democratic Party. The Tammany Hall politicians focused on bringing immigrants, most notably the Irish, into American politics from the 1850s, and into the 1960s. Tammany Hall politicians virtually controlled the Democratic nominations and political patronage in Manhattan for over 100 years following the mayoral victory of Fernando Wood in 1854. These politicians used their patronage resources to build a loyal, well-rewarded core of district and precinct leaders, and after 1850, the vast majority were Irish Catholics due to mass immigration from Ireland during and after the Irish Famine of the late 1840s.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, Sickles raised a brigade with himself as its commander, hoping to improve his reputation, which had suffered greatly when he murdered his wife’s lover. On July 2, Sickles’s III Corps was ordered to defend a portion of Cemetery Ridge. This area included Little Round Top, and it was a central position between two other divisions. It seemed like the perfect strategy, but Sickles, feeling that the lay of the land made his position indefensible, asked Major General George S Meade for permission to advance three-quarters of a mile to the Emmitsburg Road. When Meade refused, Sickles ended up advancing, against a direct order, to the forward position anyway. That shift of position left his unit vulnerable to flanking attacks and also left Little Round Top undefended. Clearly, Sickles didn’t understand the strategies of war that were well known to Major General Meade. I guess soldiers are promoted for a reason.

Sickles was forced to retreat and lost almost 40% of his force in the Confederate attack that followed. After Sickles had abandoned his post, the task of defending Little Round Top fell to the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, V corps, and in fact made famous the 20th Maine brigade, under Colonel Joshua Chamberlain. In the end, they famously managed to repel the Confederate advance, but the victory would not have needed the heroics if Sickles had stayed at his post. Of course, typical of those who rebel and ignore the orders given, Sickles

maintained to the end of his days that his insubordination helped the Army of the Potomac survive the day’s assaults. It was a crazy declaration, but I guess it helped him sleep at night. There are those on both sides of the coin on that one, but in the end, the disobedience cost him much more than he might have imagined, since he was never the president.

maintained to the end of his days that his insubordination helped the Army of the Potomac survive the day’s assaults. It was a crazy declaration, but I guess it helped him sleep at night. There are those on both sides of the coin on that one, but in the end, the disobedience cost him much more than he might have imagined, since he was never the president.

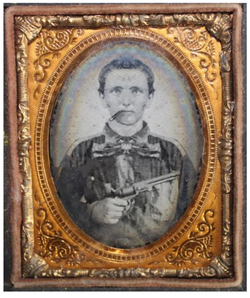

There are some people who are just mean. You can’t look at it any other way. Cullen Montgomery Baker was one of those mean men…a cold-blooded and ruthless killer who left a long trail of bodies across the American Frontier. Baker was a Confederate guerrilla during the Civil War, but he didn’t want to give up the fight once the war was over, so afterward he ambushed reconstructionists, killed former slaves, and generally terrorized the states of Texas and Arkansas for four years.

There are some people who are just mean. You can’t look at it any other way. Cullen Montgomery Baker was one of those mean men…a cold-blooded and ruthless killer who left a long trail of bodies across the American Frontier. Baker was a Confederate guerrilla during the Civil War, but he didn’t want to give up the fight once the war was over, so afterward he ambushed reconstructionists, killed former slaves, and generally terrorized the states of Texas and Arkansas for four years.

Born in Weakley County, Tennessee, on June 22, 1835, to John Baker and his wife, Elizabeth, his father was an honest but poor farmer who also owned cattle. The family moved to Clarksville, Arkansas soon after he was born. Times were no better there, so in 1839, after just a few years, the family moved to Texas, eventually settling in Davis County. There, things looked like they might get better when his father received a land grant of 640 acres, but even with the acreage, the family was still poor, and because of his homespun trousers and bare feet, Cullen was teased by students at school, probably triggering his anger. Though he was a slender and withdrawn youth, he began to fight back. It was at this time, that he obtained an old pistol and a rusty but workable rifle. He practiced diligently until he was very proficient with both weapons.

At the tender age of 15 years, Baker began to drink whiskey. Emboldened by alcohol, he began to challenge both boys and men who annoyed him to “go for your guns.” As often happens when people get hooked on alcohol, he spent much of his time in saloons, where his quick temper got him into several brawls. Soon, he was well known as a hard drinker, a braggart, and generally a quarrelsome and mean-spirited young man. He almost learned his lesson in one fight, when he was knocked unconscious by a man named Morgan Culp, who hit him in the head with a tomahawk. This incident seemingly calmed his temper for a little while, or maybe scared him a little bit, but that wouldn’t last.

Baker was rather a spontaneous man, and so some weeks later, on January 11, 1854, while still wearing a head bandage from the tomahawk incident, Baker married 17-year-old Martha Jane Petty and settled down to a quiet farming life. It looked like the marriage might have been the turnaround moment for him, but he grew tired of this routine and was back to his old ways just eight months later. One night when he was out drinking, he got into an argument with a teenager named Stallcup. As the discussion devolved, Baker became enraged. He grabbed a whip and beat the boy nearly to death. For that, Baker was charged with the crime. He went to the home of witness, Wesley Bailey, and shot him in both legs with a shotgun. He then left him lying in front of his house. Bailey died a few days later, but before Baker could be arrested for the murder, he fled to Perry County, Arkansas, where he hid out at the home of his mother’s brother, Thomas Young, for almost two years.

While there, not bothering to lay low, he stabbed a man named Wartham to death in an argument about horses in 1856 and fled back to Texas. His stay in Texas was short-lived, when he learned he was still wanted for murder in the killing of Bailey, so he returned to Arkansas. While he was gone, his wife Martha gave birth to a baby girl, Louisa Jane, on May 24, 1857. Returning to Texas briefly the following year, he retrieved his wife and daughter. Unfortunately, his wife died on July 2, 1860, and Baker took their child to Sulphur County, Texas. He left her with his in-laws, and that was the last he saw of her. I’m sure his in-laws were thankful for that.

In November 1861, Baker joined Company G of Morgan’s Regimental Cavalry to fight in the Confederate Army. In July 1862, he married a second time to Martha Foster, who was unaware he was wanted for murder. Baker’s name appears on the muster roll for September-October 1862, and he actually received pay through August 31, but by January 10, 1863, he had deserted and was listed on the muster roll as such.

It was at this point that Baker joined a guerilla group called the “Independent Rangers,” loosely associated with the Confederate Home Guard. My guess is that the Confederate regular army was a little “too tame” for his kind of fighting. The guerilla group suited his style better, as their objective was to pursue and capture deserters from the Confederate Army. That work held no real interest for Baker, but it allowed him a certain measure of freedom to do what he really wanted to do, which was to take advantage of most of the men being away at war and committing atrocities of intimidation, rape, theft, and violence. Any man who had property was considered an enemy and was declared to be a Union man to Baker, and therefore fair game. The attacks in some areas became so bad that everyone who could, left the area. Then, shortly after Baker joined the “Independent Rangers,” they began an ongoing feud with another band called the “Mountain Boomers,” who were Union guerrillas…basically having their own war between the North and South. Both bands ran throughout Arkansas, robbing, burning, and murdering indiscriminately…and fighting with each other.

In November 1864, a small band of mostly old men, women, and children, who were trying to escape from the turmoil, started west with their teams and valuables. When the group crossed the Saline River in the Ouachita Mountains, Cullen Baker and the Independent Rangers caught up to them. Baker’s story was that he and his men considered the group’s attempted escape “unpatriotic,” but, in reality, they needed little reason to harass them. When the group refused to return to their homes, Baker drew his pistol and shot and killed their leader. He then assured the rest of the group that he would not kill anyone else, if they agreed to return to their homes. But being the liar he was, as soon as the settlers returned to Baker’s side of the river, he led his  “Rangers” in shooting and killing nine other men and stealing all the valuables. The event became known locally as the Massacre of Saline.

“Rangers” in shooting and killing nine other men and stealing all the valuables. The event became known locally as the Massacre of Saline.

It was at this point that the local citizens had had enough. The began to organize and make active preparations to take out the murderous gang. However, being the stellar, brave men they were, when the ruffians got word of this, they ran, taking their booty and the many horses and mules they had stolen with them.

At the end of 1864, Baker was seen in a saloon wearing a Confederate hat in Spanish Bluffs, Arkansas. He was approached by four African American Union soldiers who asked for identification. With his pistol drawn, Baker turned to face them, shooting and killing a sergeant and the three other soldiers. One report tells that when the war was over, as he was making his way home, he came upon a group of travelers in Sevier County, Tennessee. In the group was a black woman who he began to verbally harass and then shot and killed her.

Following this rampage, he settled down with his wife Martha near the Sulphur River area in southwestern Arkansas, where he became the manager of the Line Ferry. Again, this break from the violence was short-lived. Martha soon took ill and died on March 1, 1866. Apparently, Baker very much-loved Martha and grieved her loss deeply. Still, losing his second wife didn’t stop him from proposing to her 16-year-old sister, Belle Foster, just two months later. Belle rejected his proposal and instead married a schoolteacher and political activist named Thomas Orr. This enrages Baker, who began to harass Orr, trying to pick fights with the man, hitting him over the head with a tree limb, and going to his school to ridicule, curse, and threaten the man in front of his students. I’m sure Belle Foster was thankful she married the man she did, after seeing the horrible acts of the man who had married her older sister.

Reconstruction had begun in Arkansas and Texas around this time, and Baker despised the idea. He and another outlaw named Lee Rames organized a gang that operated out of the Sulphur River bottoms near Bright Star, Arkansas. Baker continued his acts of robbery and murder, along with the Rames gang. They were said to have killed at least 30 people, many of whom were outnumbered, ambushed, or shot in the back. Baker and his gang also traveled to Texas, where he killed John Salmons in retaliation for the killing of Seth Rames, who was the brother of gang member Lee Rames. Baker also killed WG Kirkman, a Reconstruction official, and a man named George W Barron, who had previously taken part as a member of a posse hunting him. Baker was “happy” to kill anyone who annoyed him, or who might have annoyed someone he knew, or might have done the slightest thing against him…real or perceived. The gang continued their outlaw spree in Queen City, Texas, and Texarkana, Arkansas.

On June 1, 1867, he returned to Cass County. In need of supplies, Baker entered the Rowden General Store, helped himself to some items without paying. The proprietor, John Rowden rode with a shotgun to Baker’s house and demanded payment. Seemingly compliant, Baker said he would come back and pay him, but on June 5, he killed Rowden instead. Again, Baker fled to Arkansas, where he recognized by a Union sergeant when he boarded a ferry. He killed the Union officer, but a private was able to get away and reported the murder. With the eyewitness account, Baker became a hunted man, pursued relentlessly by Union forces.

On July 25, 1867, following an argument with several Union Soldiers near New Boston, Texas, which quickly escalated to violence, Baker was shot in the arm in a gunfight in which he killed army Private Albert E Titus. A $1,000 reward was set for his capture, dead or alive.

In December 1867, Baker went to Bright Star, Arkansas, where he met up with several men who were planning a raid on the farm of Howell Smith. They were upset because Smith had hired several freed slaves. In the attack, one of Smith’s daughters was stabbed, another clubbed, and a black man was shot and killed. Still, Smith resisted, and in the ensuing shootout, several of the raiders were wounded, including Baker, who was shot in the leg.

On October 24, 1868, Baker and his gang were reported to have been involved in the killings of Major P J Andrews, Lieutenant H F Willis, and an unnamed black man in Little Rock, Arkansas. Wounded in the attack was Sheriff Standel.

By this time, Baker’s co-leader, Lee Rames, began to get nervous about Baker’s leadership style and felt that his actions would lead to the downfall of the entire gang. Rames defied Baker, who backed down, and the gang broke up in December 1868. All members, except “Dummy” Kirby, sided with Rames. Baker and Kirby went to Bloomburg, Texas, to the house of Baker’s in-laws in January 1869. It would be there that Cullen Baker and “Dummy” Kirby would die on January 6, 1869.

Exactly how they were killed is unknown. One version says that “his father-in-law and friends laced a bottle of whiskey and some food with strychnine and both men died from poisoning. Afterward, their bodies were riddled  with bullets. Another version says that Thomas Orr, with whom Baker had long feuded, led a small band of men who ambushed Baker and Kirby at the Foster home, shooting and killing them.” In reality, it doesn’t matter how they died, because so many people were glad that Baker was gone, that after the men were killed, their bodies were dragged through the town of Bloomburg and then taken to the US Army outpost near Jefferson, where they were placed on public display. Thomas Orr was said to have collected some of the reward money offered for Baker. Baker was buried in the Oakwood Cemetery in Jefferson, Texas. Though he was a deserter from Morgan’s Squadron, the Confederate cavalry unit is shown on his grave marker.

with bullets. Another version says that Thomas Orr, with whom Baker had long feuded, led a small band of men who ambushed Baker and Kirby at the Foster home, shooting and killing them.” In reality, it doesn’t matter how they died, because so many people were glad that Baker was gone, that after the men were killed, their bodies were dragged through the town of Bloomburg and then taken to the US Army outpost near Jefferson, where they were placed on public display. Thomas Orr was said to have collected some of the reward money offered for Baker. Baker was buried in the Oakwood Cemetery in Jefferson, Texas. Though he was a deserter from Morgan’s Squadron, the Confederate cavalry unit is shown on his grave marker.

Some people have romanticized him for his defense of the “Southern honor,” but the reality is that Baker was a ruthless killer who killed anyone who angered him, regardless of their loyalties. It is thought that he killed between 50-60 people, and authorities and historians alike rank him among the most ruthless killers who ever lived.

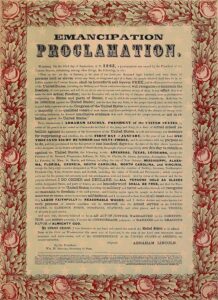

The Civil War was fought for a number of reasons, but the biggest reason was the slave issue. During the war between the North and South, came President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and the freedom of the slaves…well, most of them, anyway. Of course, things like this come in stages. The Proclamation had the effect of “changing the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as slaves escaped the control of their enslavers, either by fleeing to Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, they were permanently free. In addition, the Proclamation allowed for former slaves to ‘be received into the armed service of the

The Civil War was fought for a number of reasons, but the biggest reason was the slave issue. During the war between the North and South, came President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and the freedom of the slaves…well, most of them, anyway. Of course, things like this come in stages. The Proclamation had the effect of “changing the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as slaves escaped the control of their enslavers, either by fleeing to Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, they were permanently free. In addition, the Proclamation allowed for former slaves to ‘be received into the armed service of the  United States.’ The Emancipation Proclamation played a significant part in the end of slavery in the United States.”

United States.’ The Emancipation Proclamation played a significant part in the end of slavery in the United States.”

This all seemed simple enough, if the slave could escape, but they had to know about the Emancipation Proclamation, and the slaveowners in Texas decided not to tell them that they could be free. The Proclamation had the effect of changing the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as slaves escaped the control of their enslavers, either by fleeing to Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, they were permanently free. In addition, the Proclamation allowed for former slaves to “be received into the armed service of the United States.” The people of Texas kept their slaves in the dark about everything, including the end of the Civil War Major General Gordon Granger, who had been tasked with enforcing the Emancipation Proclamation. Granger arrived in Galveston until June 19, 1865, where he formally announced that the slaves were free according to  General Order Number 3. It was the first time many of them had heard this good news. Texans began celebrating June 19th as Juneteenth since that time. It became a state holiday in 1979.

General Order Number 3. It was the first time many of them had heard this good news. Texans began celebrating June 19th as Juneteenth since that time. It became a state holiday in 1979.

On April 8, 1864, by the necessary two-thirds vote, the Senate passed the 13th Amendment. The House of Representatives passed it on January 31, 1865, and the required three-fourths of the states ratified it on December 6, 1865. The amendment made slavery and involuntary servitude unconstitutional, “except as a punishment for a crime.”

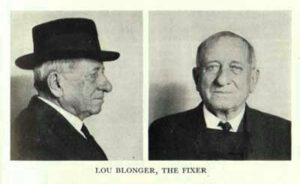

Louis H Blonger was born in Swanton, Vermont, on May 13, 1849. He was the eighth of 13 children. His father, Simon Peter Belonger, was a stonemason born in Canada of French ancestry. His mother, Judith Kennedy, was raised in an orphanage in Nenagh, County Tipperary, Ireland. The Belonger family migrated from Vermont to the lead mining village of Shullsburg, Wisconsin, when Lou was five years old. Sadly, his mother died in 1859, and Lou was sent to live with his older sister and her husband for a few years. It was around that time, that Blonger began using a shortened version of the family name (omitting the first “e”), as most of his brothers did.

Louis H Blonger was born in Swanton, Vermont, on May 13, 1849. He was the eighth of 13 children. His father, Simon Peter Belonger, was a stonemason born in Canada of French ancestry. His mother, Judith Kennedy, was raised in an orphanage in Nenagh, County Tipperary, Ireland. The Belonger family migrated from Vermont to the lead mining village of Shullsburg, Wisconsin, when Lou was five years old. Sadly, his mother died in 1859, and Lou was sent to live with his older sister and her husband for a few years. It was around that time, that Blonger began using a shortened version of the family name (omitting the first “e”), as most of his brothers did.

The Civil War broke out when Lou was just 15 years old. While he was technically just a boy, Lou enlisted in the Union Army anyway. While he was a soldier, someone must have known that he was quite young, and he soon found himself playing a musical instrument called a fife, helping to keep the marching pace of the soldiers. A Fifer was a common job for those boys who were too young to fight. When the war ended, Lou joined up with his older brother, Sam. The boys headed west hoping to make their fortunes in the many Colorado, Utah, and Nevada mining camps. As they were about to find out, mining isn’t the easiest way to make “your fortune” and so they found themselves moving from camp to camp, taking various jobs working in saloons and mines while doing a little prospecting, plenty of gambling, and practicing several con games in cities across the West, from Deadwood, South Dakota, to Silver City, New Mexico, and on to San Francisco, California. For a short time, Lou and Sam even served as lawmen in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where they were said to have provided protection for Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp.

The brothers could be found in Denver, Colorado by the 1880s, where they ran a saloon on Larimer Street and later on Stout Street. Within ten years, they had become wealthy from their investments in mining claims, as well as their profits from their popular Denver saloons. Their saloons catered to gamblers and provided “painted ladies” for their customers, but it was far more due to their various games of fraud and graft practiced on many  a hapless miner, that brought in the most money for the pair. While in Denver, they practiced their cons widely, in open competition with the well-known Soapy Smith Gang. Eventually, the Blonger brothers took over control as the “Kingpins” of the Denver underworld, when Soapy Smith moved on in 1896. They consolidated the city’s competing gangs of confidence men into a single organization.

a hapless miner, that brought in the most money for the pair. While in Denver, they practiced their cons widely, in open competition with the well-known Soapy Smith Gang. Eventually, the Blonger brothers took over control as the “Kingpins” of the Denver underworld, when Soapy Smith moved on in 1896. They consolidated the city’s competing gangs of confidence men into a single organization.

Operating their “business” as a “big store” con, or fake betting house, central facilities were established, complete with betting windows, chalkboards for race results, and ticker-tape machines. Here, the gang members would convince unsuspecting customers to put up large sums of cash to secure the delivery of promised stock profits or winning bets on horse races. It was this practice that is portrayed in the movie, The Sting. Lou also had several men working for him who profited as pickpockets, shell-game experts, and other small-time con games. Lou’s operation was so tight that no one could operate in the city without gaining his permission and “donating” a share of their proceeds to him. Not satisfied with their original influence, they began to wield their power by influencing elections and political appointments to protect their racket and shield their gang members from prosecution.

Blonger added a second-in-command, named Adolph W “Kid” Duff in 1904. Duff was an experienced hand, having long been a member of several other Colorado gangs and well known as a gambler, opium dealer, and pickpocket. With this addition, the profits of the “organization” increased, and by 1920, Lou Blonger had grown so powerful that many said he “owned” the city of Denver. He was said to be able to fix any arrest with a phone call and was making thousands of illegal dollars a year in his extensive confidence games. Lou even had a private telephone line in his office that ran directly to the chief of police…who was also corrupt. Lou had become known as “The Fixer” and had become one of the leaders of the longest-running confidence rings in the American West. Nevertheless, even this was a doomed enterprise.

Blonger had been a decent young man turned successful criminal for decades, when in 1922, it all ended. Di

strict Attorney Philip S Van Cise circumvented the corrupt Denver politicians and established his own “secret force” of local citizens. They were funded by private donations, an Van Cise’s men were able to arrest 33 confidence men, including Louis Blonger and “Kid” Duff. The trial was big news and highly publicized. The people were tired of the corruption, and upon their conviction, Louis Blonger and many other gang members were sentenced to prison in Cañon City, Colorado. Lou Blonger and “Kid”, Duff received sentences of seven to ten years, nevertheless, Blonger would again escape hi “due punishment” when just five months after going to prison, he died on April 20, 1924, at the age of 74. Duff, in the meantime, was out on bond pending another court case, when he committed suicide. You might be wondering what Lou’s older brother Sam was doing at this time. Sam had died some ten years earlier.

strict Attorney Philip S Van Cise circumvented the corrupt Denver politicians and established his own “secret force” of local citizens. They were funded by private donations, an Van Cise’s men were able to arrest 33 confidence men, including Louis Blonger and “Kid” Duff. The trial was big news and highly publicized. The people were tired of the corruption, and upon their conviction, Louis Blonger and many other gang members were sentenced to prison in Cañon City, Colorado. Lou Blonger and “Kid”, Duff received sentences of seven to ten years, nevertheless, Blonger would again escape hi “due punishment” when just five months after going to prison, he died on April 20, 1924, at the age of 74. Duff, in the meantime, was out on bond pending another court case, when he committed suicide. You might be wondering what Lou’s older brother Sam was doing at this time. Sam had died some ten years earlier.

Most of us think that after the Civil War, the South simply accepted defeat and went on to become model citizens of the new America…the one without slavery. That was not the case, however. First of all, there were a number of plantation owners in the South, who just didn’t tell their slaves that they were free now. Finally, after being forced to do so, the announcement came, a whole two months after the effective conclusion of the Civil War, and even longer since Abraham Lincoln had first signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Nevertheless, even after that day, many enslaved black people in Texas still weren’t free. That part was bad enough, but that wasn’t all there was to it.

Most of us think that after the Civil War, the South simply accepted defeat and went on to become model citizens of the new America…the one without slavery. That was not the case, however. First of all, there were a number of plantation owners in the South, who just didn’t tell their slaves that they were free now. Finally, after being forced to do so, the announcement came, a whole two months after the effective conclusion of the Civil War, and even longer since Abraham Lincoln had first signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Nevertheless, even after that day, many enslaved black people in Texas still weren’t free. That part was bad enough, but that wasn’t all there was to it.

We have heard people say that if this or that president gets into office, they are leaving the country. People have also left the country because they didn’t want to fight is a war. However, I had never heard that  approximately 20,000 Confederates decided to actually leave the country. They went to Brazil after the Civil War to create a kingdom built on slavery. These people were so set on their lifestyle that they were willing to pull up stakes and start over in order to keep their slaves and their slavery lifestyle. The reality was that after four bloody years of war, the Confederacy virtually crumbled in April 1865. Nevertheless, a rather large group of the Confederates were not ready to accept defeat.

approximately 20,000 Confederates decided to actually leave the country. They went to Brazil after the Civil War to create a kingdom built on slavery. These people were so set on their lifestyle that they were willing to pull up stakes and start over in order to keep their slaves and their slavery lifestyle. The reality was that after four bloody years of war, the Confederacy virtually crumbled in April 1865. Nevertheless, a rather large group of the Confederates were not ready to accept defeat.

Instead, as many as 20,000 of them fled south. They relocated to Brazil, where a slaveholding culture already existed. There, they hoped the country’s culture could help them preserve their traditions. Once there, they cooked Southern food, spoke English, and tried to buy enough slaves to resurrect the pre-Civil War plantation system. These people, known as Confederados, were enticed to Brazil by offers of cheap land from Emperor Dom Pedro II, who had hoped to gain expertise in cotton farming. Initially, most of these so-called Confederados settled in the current state of São Paulo, where they founded the city of Americana, which was once part of the neighboring city of Santa Bárbara d’Oeste. The descendants of other Confederados would later be found throughout Brazil. They were very happy with their decision to leave the United States, and very

happy that they could continue to keep slaves. Nevertheless, their “victory” was not without loss too. They had to give up their citizenship in the United States, and I have to wonder if their lives have turned out as they hoped they would, or if they are living in much poorer conditions in Brazil. Nevertheless, they stayed, and to this day, the so-called Confederados gather each year to fly the Confederate flag and celebrate their lost heritage.

happy that they could continue to keep slaves. Nevertheless, their “victory” was not without loss too. They had to give up their citizenship in the United States, and I have to wonder if their lives have turned out as they hoped they would, or if they are living in much poorer conditions in Brazil. Nevertheless, they stayed, and to this day, the so-called Confederados gather each year to fly the Confederate flag and celebrate their lost heritage.

I am of the opinion that most of the United States is populated by good people, who are trying to lead decent and respectful lives. I’m sure there are those who would disagree, and when faced with evil doers, it is sometimes hard to see the good because of the bad, but I think we can agree that the people who agreed with the northern states during the Civil War, far outnumbered those who agreed with the southern states. the Union had a distinctive advantage over the Confederates. There were more states and more soldiers in the Union Army. So, the Confederate Army had to find a way to get ahead of their enemies. Confederates sometimes relied on technical innovation to aid their cause, in the face of such limited resources compared with the Union Army’s sheer numbers and resources. The Union had $234,000,000 in bank deposit and coined money while the Confederacy had $74,000,000 and the Border States had $29,000,000. The Union Army had 2,672,341 soldiers, as opposed to the Confederate Army, which had between 750,000 to 1,227,890 soldiers.

I am of the opinion that most of the United States is populated by good people, who are trying to lead decent and respectful lives. I’m sure there are those who would disagree, and when faced with evil doers, it is sometimes hard to see the good because of the bad, but I think we can agree that the people who agreed with the northern states during the Civil War, far outnumbered those who agreed with the southern states. the Union had a distinctive advantage over the Confederates. There were more states and more soldiers in the Union Army. So, the Confederate Army had to find a way to get ahead of their enemies. Confederates sometimes relied on technical innovation to aid their cause, in the face of such limited resources compared with the Union Army’s sheer numbers and resources. The Union had $234,000,000 in bank deposit and coined money while the Confederacy had $74,000,000 and the Border States had $29,000,000. The Union Army had 2,672,341 soldiers, as opposed to the Confederate Army, which had between 750,000 to 1,227,890 soldiers.

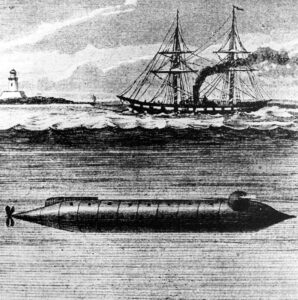

Given the obvious lop-sidedness, especially in the naval conflict, the Confederates could not hope to match the Union in sheer tonnage of ships produced. They didn’t have the funds or the resources to build as many ships as the Union. Many people would actually assume that either the Confederates would lose the war quickly, or it would be mostly fought on land. The Confederates, however, did come up with two famous Confederate naval  innovations…the ironclad warship, CSS Virginia and the submarine, HL Hunley. The HL Hunley was built in 1863. Who would have thought there would be a submarine built that early on.

innovations…the ironclad warship, CSS Virginia and the submarine, HL Hunley. The HL Hunley was built in 1863. Who would have thought there would be a submarine built that early on.

Of course, the Union wasn’t sitting around doing nothing while the Confederates dominated the water. They were busy too. The USS Monitor was built around the same time the Virginia was being retrofitted with iron plating, and those two ships actually clashed at the Battle of Hampton Roads. While the Confederates did get in the war ship game, the superior Northern industrial capacity allowed them to build more than 80 ironclads. The North also built a submarine, called the USS Alligator. It was designed by French engineer Brutus de Villeroi, who had, amazingly, been working on submersible craft for some 30 years. Contrary to what we might think, the concept of a submarine was not a new one. In fact, there was even a primitive one employed in the American War of Independence. The submarines were a far cry from the huge 20th-century submarines of today.

The Alligator was based on an 1859 prototype and was commissioned in 1861 as part of the same flurry of  naval innovation that saw the creation of the ironclad Monitor. The Alligator featured an innovative air-purification system that used limewater to remove carbon dioxide and keep the air breathable for long periods. The Alligator was manned by a 16-member crew, which was later reduced to eight. Also unusual is the fact that USS Alligator had oars to maneuver with. I suppose that wouldn’t seem unusual in its day, but it certainly does today. Sent out on a mission to remove obstructions in Charleston Harbor in advance of an attack by a Union ironclad fleet, the Alligator ran into trouble in the form of a gale on April 2, 1863, while being towed to nearby Port Royal, South Carolina. It was in the storm, and its wreckage was never recovered…but the hunt is ongoing.

naval innovation that saw the creation of the ironclad Monitor. The Alligator featured an innovative air-purification system that used limewater to remove carbon dioxide and keep the air breathable for long periods. The Alligator was manned by a 16-member crew, which was later reduced to eight. Also unusual is the fact that USS Alligator had oars to maneuver with. I suppose that wouldn’t seem unusual in its day, but it certainly does today. Sent out on a mission to remove obstructions in Charleston Harbor in advance of an attack by a Union ironclad fleet, the Alligator ran into trouble in the form of a gale on April 2, 1863, while being towed to nearby Port Royal, South Carolina. It was in the storm, and its wreckage was never recovered…but the hunt is ongoing.

When you think about the Civil War, you think of battles being fought back east…right? For the most part, it was. When the war began, there were 34 states, but by the end, there were 36 states. Of course, some of the Southern states, eleven to be exact, wanted to secede and form their own country. That was partly what the war was about. The Southern states wanted to keep slavery, and the Northern states did not, and because they could not agree, eleven states chose to secede, and the rest fought to keep our nation together.

When you think about the Civil War, you think of battles being fought back east…right? For the most part, it was. When the war began, there were 34 states, but by the end, there were 36 states. Of course, some of the Southern states, eleven to be exact, wanted to secede and form their own country. That was partly what the war was about. The Southern states wanted to keep slavery, and the Northern states did not, and because they could not agree, eleven states chose to secede, and the rest fought to keep our nation together.

Some of the battles were fought, however on the far western front. The first of those battles, was on February 21, 1862. In the Battle of Valverde, Confederate troops under General Henry Hopkins Sibley attacked Union troops commanded by Colonel Edward R S Canby near Fort Craig in the New Mexico Territory. This first major engagement of the Civil War in the far West, produced heavy casualties but ended with no decisive result. Of course, the battle was part of the broader movement by the Confederates to capture New Mexico and other parts of the West. The point was to secure territory that the Rebels thought was rightfully theirs, because it was part of the southern territories of the United States. This area had been denied them by political compromises made before the Civil War, which they felt was wrong.

By this time, the Confederacy was quickly going broke, and they wanted to use Western mines to fill its treasury. The Rebel troops moved from San Antonio, into southern New Mexico, which at that time included Arizona, and captured the towns of Mesilla and Tucson. Sibley, with 3,000 troops, now moved north against the Federal stronghold at Fort Craig on the Rio Grande. Canby was determined to make sure the Confederates didn’t lay siege to Fort Craig. Canby knew that the Rebels were running low on supplies, and they wouldn’t last much longer. He knew that Sibley really did not have sufficiently heavy artillery to attack the fort, so when Sibley arrived near Fort Craig on February 15, he ordered his men to swing east of the fort, cross the Rio Grande, and capture the Valverde fords of the Rio Grande. He hoped to cut off Canby’s communication and force the Yankees out into the open, thereby giving the Rebels the upper hand.

For Sibley’s Rebels, things at the fords didn’t initially go as planned. Five miles north of Fort Craig, a Union detachment attacked part of the Confederate force. The Yankees pinned the Texan Rebels in a ravine and were on the verge of routing them when more of Sibley’s men arrived and turned the tide. Sibley’s second in command, Colonel Tom Green, who was filling in for Sibley, who was ill, made a bold counterattack against the Union left flank. The Yankees retreated, heading back to Fort Craig. Sibley’s men didn’t take Fort Craig either.

During the Battle of Valverde, out of 3,100 men, the Union suffered 68 killed, 160 wounded, and 35 missing.

The Confederates suffered 31 killed, 154 wounded, and 1 missing out of 2,600 troops. The battle was indeed bloody, but none of their objectives were accomplished, so it was virtually an indecisive battle. From Fort Craig, Sibley’s men continued up the Rio Grande winning battle after battle. Nevertheless, after capturing Albuquerque and Santa Fe, they were stopped at the Battle of Glorieta Pass on March 28, 1862.

The Confederates suffered 31 killed, 154 wounded, and 1 missing out of 2,600 troops. The battle was indeed bloody, but none of their objectives were accomplished, so it was virtually an indecisive battle. From Fort Craig, Sibley’s men continued up the Rio Grande winning battle after battle. Nevertheless, after capturing Albuquerque and Santa Fe, they were stopped at the Battle of Glorieta Pass on March 28, 1862.

Politics can be a touchy subject. Many arguments have come from political disagreements, and in fact, a number of actual fights and even wars have been fought over political disagreements. The Civil War was one sch war fought over political views. During that time there were also a number of private disputes as well. Sumner Pinkham was in volved on one of those disputes. Sumner Pinkham was born in 1820 in the state of Maine and was raised in Wisconsin. Very little, if anything, is known about his early life. He married Laurinda Maria Atwood in Nebraska on November 4, 1842. In 1849, Pinkham joined the California gold rush and then spent time in Oregon before making his way to the booming gold rush camp of Idaho City in 1862. Pinkham was a big man…powerfully built, who stood six feet two inches tall and had a barrel chest. He was also prematurely gray, making him look older than he really was.

Politics can be a touchy subject. Many arguments have come from political disagreements, and in fact, a number of actual fights and even wars have been fought over political disagreements. The Civil War was one sch war fought over political views. During that time there were also a number of private disputes as well. Sumner Pinkham was in volved on one of those disputes. Sumner Pinkham was born in 1820 in the state of Maine and was raised in Wisconsin. Very little, if anything, is known about his early life. He married Laurinda Maria Atwood in Nebraska on November 4, 1842. In 1849, Pinkham joined the California gold rush and then spent time in Oregon before making his way to the booming gold rush camp of Idaho City in 1862. Pinkham was a big man…powerfully built, who stood six feet two inches tall and had a barrel chest. He was also prematurely gray, making him look older than he really was.

Pinkham was a conservative Republican, a Unionist, and an abolitionist, which put him on the opposite side of the majority of Boise Basin mining camps political views, which were predominantly Democrat. When Pinkham arrived in the Idaho City area, Idaho was still a part of Washington Territory, and the Boise Basin was located in Idaho County, of which Florence was the county seat. Florence was located a way away from the new mining basin, so the Washington Legislature established Boise County on January 29, 1863.

After being in the area for a while, and becoming known for his political views, the Governor of Washington was assigning commissioners and officers to the newly established county, and Pinkham was one of them, assigned to serve as the County Sheriff. On March 4, 1863, Congress created Idaho Territory. At that time Boise County exceeded the other counties in both area and in population. Those in office in Boise County at the time, including Pinkham, retained their positions until the territorial government could be officially organized. Pinkham appointed Orlando “Rube” Robbins, who shared his political opinions, as his deputy in August 1863. Robbins would later make himself known as one of Idaho’s greatest lawmen.

By this time, the Civil War was raging back East, and the area miners began to choose sides, around the Union and Confederate causes. This, dueled with whiskey, caused flair-ups between North and South sympathizers, bring with it fist fights, knife fights, and sometimes gun battles as they used force to show their opinions. That kept both Pinkham and his deputy, Rube Robbins, busy breaking up fights and locking up drunken loudmouths as they threatened to fight it out…to the death. The area being predominately Democrat often placed Pinkham at odds with his constituents due to his staunch Unionist views, Republican politics, and tough law enforcement. His list of enemies grew. Nevertheless, both Pinkham’s enemies and his most loyal friends knew that he was a man they shouldn’t mess with when he undertook to enforce the law, which he did with an iron hand.

His greatest enemy was a Southern gunfighter named Ferdinand “Ferd” Patterson. On one occasion, while Patterson was partying with some of his friends in Idaho City, they took unlawful possession of a brewery in Idaho City. Sheriff Pinkham was called by the owner to remove the rowdy group. When Pinkham entered the brewery, he was met with violent resistance. Pinkham and Patterson immediately hated each other. Patterson was Southerner who was crooked by nature, and Pinkham was a Northerner who tended to be self-righteous. In the end, Pinkham was successful, and Patterson was arrested. When Pinkham lost his October 1864 for re-election as Boise County Sheriff, in a bitter contest between the Democratic successionists and Republican candidates. Pinkham was defeated by A O Bowen by a comfortable majority, and Patterson celebrated, as the last of the ballots were being counted. When Patterson encountered his old nemesis, he began rubbing it in. Pinkham, who was in a rage, swung at Patterson, hitting him in the jaw and throwing the gambler off the street and into the gutter. After that, Pinkham walked away. Everyone expected Patterson to retaliate, but he let it go…for then. Pinkham left Idaho City, following the lost election, heading to Illinois to visit his dying mother. When he returned in 1865, everyone figured they would have it out, but it didn’t happen then either.

After the Civil War ended, Pinkham held a huge Fourth of July party. The crowds were mostly festive, with fireworks blazing and booze abundant. The celebration included a brass band, speeches, patriotic songs, a picnic, and a parade with Pinkham leading the way through town. For the victorious Yankees, it was a proud day. But, for the sullen Confederate sympathizers…not so much. To make matters worse, the Yankee’s heckled the “Blue Bellies” throughout the day. Patterson was furious as he watched Pinkham leading the parade through town. Pinkham singing, “Oh, we’ll hang Jeff Davis to a sour apple tree!” was the last straw. Patterson yelled out to the ex-sheriff that if “he didn’t shut his mouth, he’d shut it for him.” Pinkham invited him to try, and he did. A brief fist fight between the two men resulted in the flag falling into the dust of the street. Some witnesses swore they saw Patterson spit on it, and others attested they heard Pinkham swear he would kill Patterson for that, but nothing more came of it at that time. Several weeks later, on Sunday, July 23rd, Pinkham took a hired carriage from Idaho City to the Warm Springs Resort, which was about two miles west of town. Upon his arrival, Pinkham joined a number of his Unionist friends in the saloon, where they were heard singing patriotic and anti-Confederate songs.

Sometime later, Patterson entered the resort while Pinkham was paying his bill. Initially, Patterson ignored Pinkham, but by the time the ex-sheriff exited the resort, Patterson was outside waiting for him. Patterson said the word “draw” and then taunted Pinkham by calling him an “Abolitionist son-of-a-b***h.” Who drew first is in dispute, but in the end, Pinkham was dead. Patterson quickly fled but was immediately followed by several lawmen. Rube Robbins was the first to catch up to him, about 14 miles from Idaho City. Patterson surrendered to Robbins, who turned the killer over to Sheriff Bowen, who was next on the scene. Bowen and his men took over and escorted Patterson back to Idaho City.

A mob wanted to lynch him, and maybe that would have been justice, because in the “sham” trial held in a predominately Democrat area, Patterson was acquitted, and with that, justice for Pinkham would never be served. Ferd Patterson was tried for Pinkman’s murder at the beginning of November 1865. In the six-day trial, defense attorney Frank Ganahl claimed his client acted in self-defense, arguing that Pinkham was lying in wait  for him. Alternatively, Pinkham’s friends testified that he tried to avoid a showdown and that Patterson came to Warm Springs with the explicit purpose of murdering Pinkham. It took only an hour and a half for the jury to acquit Patterson. Pinkham’s funeral was the largest and most impressive funeral ever seen in the mining camp. It was reported that over 1,500 mourners followed his hearse to the graveyard. Meanwhile, knowing he was in extreme danger, Patterson quickly fled Idaho City after his acquittal. He was killed in Walla Walla, Washington, the next year, by Thomas Donahue, an area policeman, in was thought by many to be an assassination. Donahue was charged with the murder of Patterson, but escaped from jail while awaiting trial. There apparently was little interest in tracking him down. He disappeared never to be heard from again.

for him. Alternatively, Pinkham’s friends testified that he tried to avoid a showdown and that Patterson came to Warm Springs with the explicit purpose of murdering Pinkham. It took only an hour and a half for the jury to acquit Patterson. Pinkham’s funeral was the largest and most impressive funeral ever seen in the mining camp. It was reported that over 1,500 mourners followed his hearse to the graveyard. Meanwhile, knowing he was in extreme danger, Patterson quickly fled Idaho City after his acquittal. He was killed in Walla Walla, Washington, the next year, by Thomas Donahue, an area policeman, in was thought by many to be an assassination. Donahue was charged with the murder of Patterson, but escaped from jail while awaiting trial. There apparently was little interest in tracking him down. He disappeared never to be heard from again.

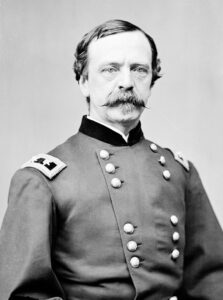

These days, it’s strange to think of battles being fought on US soil. We have begun to believe that a war, at least can’t take place on our soil anymore, because we have so many early warning systems to tell of any incoming missiles or planes, but that wasn’t always the case. The Civil War was one of the biggest wars fought on US soil, and strangely, we were fighting ourselves. Civil Wars are among the worst kinds, because there is so much anger and unrest. We have had a number of wars fought here, including the Civil War, which was clearly one of the worst on our soil. Wars are unpredictable, and the length of battles vary, with some long and drawn out, and some were just one or two days. The Battle of Nashville, Tennessee, fell into the latter category, fought on December 15 and 16, 1864, between the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Lieutenant General John Bell Hood and the Union Army of the Cumberland under Major General George H Thomas. The Battle of Nashville was part of the Franklin-Nashville Campaign.

These days, it’s strange to think of battles being fought on US soil. We have begun to believe that a war, at least can’t take place on our soil anymore, because we have so many early warning systems to tell of any incoming missiles or planes, but that wasn’t always the case. The Civil War was one of the biggest wars fought on US soil, and strangely, we were fighting ourselves. Civil Wars are among the worst kinds, because there is so much anger and unrest. We have had a number of wars fought here, including the Civil War, which was clearly one of the worst on our soil. Wars are unpredictable, and the length of battles vary, with some long and drawn out, and some were just one or two days. The Battle of Nashville, Tennessee, fell into the latter category, fought on December 15 and 16, 1864, between the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Lieutenant General John Bell Hood and the Union Army of the Cumberland under Major General George H Thomas. The Battle of Nashville was part of the Franklin-Nashville Campaign.

As far as battles go, the length does not necessarily have anything to do with the size of the victory. The Battle of Nashville was short, but it was also one of the largest victories achieved by the Union Army during the Civil War. Hood’s army was effectively destroyed when Thomas attacked and routed it as a capable fighting force. Amazingly, the Battle of Nashville was considered the only perfectly fought battle of the war, because it unfolded in “greater accordance with the victor’s battle plan” than any other clash of the war. Nashville, at that time was the second-most fortified city in America…second only to Washington DC, making the victory there an even greater one.

Although Thomas’s forces were much stronger than Hood’s army, Hood’s army was still a force to be reconned  with and could not be ignored. Hood’s army had taken a severe beating at Franklin, but it nevertheless presented a threat by its mere presence and ability to maneuver. Therefore, Thomas knew he had to attack. He prepared cautiously, because he knew that Hood was not a complete pushover, and therefore, a poorly executed plan of attack could have ended in disaster. Thomas was concerned about his cavalry corps, because they were commanded by the energetic young Brigadier General James H Wilson, but they were poorly armed and mounted, and he did not want to proceed to a decisive battle without effective protection of his flanks. This was particularly important, since Wilson would be facing the horsemen of the formidable Forrest. Still, refitting the Union cavalry took time, so he had to be patient.

with and could not be ignored. Hood’s army had taken a severe beating at Franklin, but it nevertheless presented a threat by its mere presence and ability to maneuver. Therefore, Thomas knew he had to attack. He prepared cautiously, because he knew that Hood was not a complete pushover, and therefore, a poorly executed plan of attack could have ended in disaster. Thomas was concerned about his cavalry corps, because they were commanded by the energetic young Brigadier General James H Wilson, but they were poorly armed and mounted, and he did not want to proceed to a decisive battle without effective protection of his flanks. This was particularly important, since Wilson would be facing the horsemen of the formidable Forrest. Still, refitting the Union cavalry took time, so he had to be patient.

While Thomas knew what he was doing, Washington was not so patient, and in fact, they were fuming at the seeming procrastination. It was then that Sherman proposed his March to the Sea. Ulysses S Grant and Henry Halleck objected to it, because they thought that Hood would use the opportunity to invade Tennessee. In response, Sherman airily indicated that this was exactly what he wanted and that if Hood “continues to march North, all the way to Ohio, I will supply him with rations.” It sounded like a perfect plan, however, when the ever-confident Sherman disappeared into the heart of Georgia, Grant once again became concerned about an invasion of Kentucky or Ohio. Grant later said of the situation, “If I had been Hood, I would have gone to Louisville and on north until I came to Chicago.” His concern doubtless reflected Abraham Lincoln’s concern. Lincoln had little patience for slow generals and remarked of the situation, “This seems like the McClellan and Rosecrans strategy of do nothing and let the rebels raid the country.” Still, the plan to attack Nashville seems to have been the right move.

Washington continued to pressure Hood to push forward. Then on December 8, a bitter ice storm struck Nashville, stalling the plan again. While unusual for  Nashville, the sub-freezing weather continued through December 12. Hood explained that to Grant, but when Thomas had still not moved by December 13, Grant directed that Major General John A Logan proceed to Nashville and assume command if Thomas had not yet initiated operations, by the time Logan arrived. Logan made it as far as Louisville by December 15, but on that day the Battle of Nashville had finally begun. A still impatient Grant left Petersburg on December 14, to take personal command. Apparently, he didn’t trust Logan much either. Once the battle began, Grant returned to Washington…a good thing, since three commanding officers might have been a bit awkward.

Nashville, the sub-freezing weather continued through December 12. Hood explained that to Grant, but when Thomas had still not moved by December 13, Grant directed that Major General John A Logan proceed to Nashville and assume command if Thomas had not yet initiated operations, by the time Logan arrived. Logan made it as far as Louisville by December 15, but on that day the Battle of Nashville had finally begun. A still impatient Grant left Petersburg on December 14, to take personal command. Apparently, he didn’t trust Logan much either. Once the battle began, Grant returned to Washington…a good thing, since three commanding officers might have been a bit awkward.