civil war

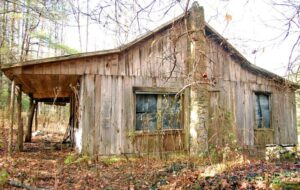

As America grew, towns popped up in many places, only to dwindle into ghost towns when the expected industry that motivated their beginning, fell through. Lost Cove was one such town. Established just before the Civil War, it was once a thriving agricultural community, but then in the early 20th century, logging replaced farming, and the railroad brought workers. Somehow in the shuffle of changes, Lost Cove found itself off the beaten path, almost hidden in the forest, with no electricity or running water. The little town had to figure out something new, and so, because of the remoteness and because the town lay on the North Carolina/Tennessee border, an equally thriving moonshine industry was born.

As America grew, towns popped up in many places, only to dwindle into ghost towns when the expected industry that motivated their beginning, fell through. Lost Cove was one such town. Established just before the Civil War, it was once a thriving agricultural community, but then in the early 20th century, logging replaced farming, and the railroad brought workers. Somehow in the shuffle of changes, Lost Cove found itself off the beaten path, almost hidden in the forest, with no electricity or running water. The little town had to figure out something new, and so, because of the remoteness and because the town lay on the North Carolina/Tennessee border, an equally thriving moonshine industry was born.

Many people might think that the moonshine industry was all due to prohibition, and that is largely true, but while bootlegging was a crime of opportunity, it was also quite likely to be a crime of necessity. Still, while moonshine could provide a living for the residents, it would never be able to sustain a whole ton for very long. Eventually, the residents of Lost Cove began to move away to laces where they could make a living. The town, now empty, seen fell into disrepair. These days Lost Cove is a graveyard of abandoned homes and crumbling gravestones. Because Lost Cove was on the border, either state could have agreed on jurisdiction to collect tax revenues, but both declined to, thereby creating a haven for bootlegging.

Even with the logging business doing well, the timber eventually thinned and the railroad service that brought passenger trains through the area stopped. With that, the Lost Cove residents became even more isolated. The nearest stores were eight miles away, and they would have to walk for basic supplies, mostly because they didn’t have money for any other form of transportation. Soon the infrastructure deteriorated too, and the rough

or non-existent roads led to even more shortages. In the end, here was nothing left, but to leave. The last known resident left in 1957. Sadly, in 2007, a fire destroyed most of what still stood in Lost Cove. All that is left now is a few structures, memories, and the history of the area, only seen by the occasional hiker, using trails that remain the only route of access.

or non-existent roads led to even more shortages. In the end, here was nothing left, but to leave. The last known resident left in 1957. Sadly, in 2007, a fire destroyed most of what still stood in Lost Cove. All that is left now is a few structures, memories, and the history of the area, only seen by the occasional hiker, using trails that remain the only route of access.

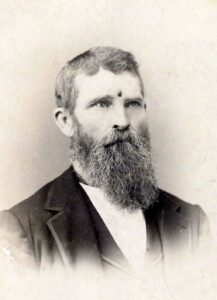

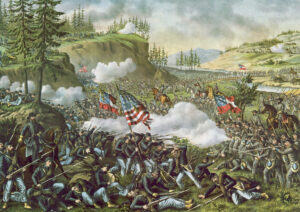

Anytime a soldier goes to war, the possibility exists that they will be severely wounded or even killed in action, but I don’t think anyone expected the events of September 19, 1863. It was the middle of the Civil War, and Jacob C Miller was a private in Company K, 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment. The company was fighting in the Battle of Chickamauga near Brock Field in southeastern Tennessee. One of the fastest ways to “get dead” is to get shot in the head. There is something about a bullet hitting the skull that puts an end to life pretty quickly…most of the time, anyway.

Anytime a soldier goes to war, the possibility exists that they will be severely wounded or even killed in action, but I don’t think anyone expected the events of September 19, 1863. It was the middle of the Civil War, and Jacob C Miller was a private in Company K, 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment. The company was fighting in the Battle of Chickamauga near Brock Field in southeastern Tennessee. One of the fastest ways to “get dead” is to get shot in the head. There is something about a bullet hitting the skull that puts an end to life pretty quickly…most of the time, anyway.

Maybe it was the type of bullets used in the Civil War, but no matter how it happened, I don’t think anyone would disagree with me when I say that living after taking a bullet between the eyes was a miracle. Jacob C Miller was just such a miracle man. After being shot, Miller crumpled to the ground. I’m sure everyone thought it was over, but Miller said later that he could hear the words of his captain, who said, “It’s no use to remove poor Miller, for he is dead.” The company, believing he was dead, moved on. Now, just imagine the shock when Miller became conscious and found himself alone. He raised up in a sitting position. Curiosity caused him to feel his wound. Clearly there was damage done. Miller’s left eye was out of place, and he tried to  place it back, but had to move the crushed bone back together, or as near together as he could first. Once the eye was in its proper place, he bandaged the eye the best he could with his bandana. Then he began the journey to get help. Miller struggled to follow his company, until he was finally picked up by a liter party, and taken for treatment.

place it back, but had to move the crushed bone back together, or as near together as he could first. Once the eye was in its proper place, he bandaged the eye the best he could with his bandana. Then he began the journey to get help. Miller struggled to follow his company, until he was finally picked up by a liter party, and taken for treatment.

When he was taken to the doctors, and they examined him, they said that they were able to see his pulsating brain quite clearly. That said, we know that the bullet wasn’t somehow stopped by his skull. It had actually entered the brain lining, or at least into the skull bone. At that point, nothing was done with the bullet, and Miller was sent home to Logansport, Indiana. Doctors there were hesitant to remove the bullet, because they thought Miller would die, and somehow, he seemed to be functioning ok with the bullet in place. In the end  they did remove about a third of the bullet, and Miller went on to live his life. Nevertheless, more pieces of the bullet simply fell out decades later. It was as if his body just rejected the foreign pieces of lead and moved them out of his head. It was a good thing, because the pressure on the bullet fragments during times of illness caused his to become delirious. Once the fragments fell out, that stopped.

they did remove about a third of the bullet, and Miller went on to live his life. Nevertheless, more pieces of the bullet simply fell out decades later. It was as if his body just rejected the foreign pieces of lead and moved them out of his head. It was a good thing, because the pressure on the bullet fragments during times of illness caused his to become delirious. Once the fragments fell out, that stopped.

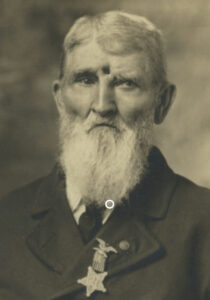

Miller was born on August 4, 1840, in Bellevue, Ohio. He was shot on September 19, 1863, at the age of 23 years. Private Jacob C Miller lived an amazing 54 years with an open wound in his head. The wound never fully healed, but did not fully penetrate his skull, and apparently the brain area did close over, and caused no damage to his brain. He died January 13, 1917, in Omaha, Nebraska at the age of 76 years. No cause of death is mentioned, but I guess we know it wasn’t a gunshot wound to the head.

Anyone who has studied history in school knows about the Civil War. It was, of course, fought over slavery. The South wanted to keep the slaves and the North wanted to free the slaves. The Civil War was unique in another way too. Most wars are fought with soldiers who are rough and tough, ready to take on the elements, and battle to the death for their cause. The Civil War was that too, but the men of the South during the Civil War Era, were part of an era of the southern belles and southern gentlemen. This was an era when a type of lifestyle was borrowed from the English countryside, and basically transplanted into the American south. The lifestyle included a glorification of elegant horse riding, hunting, and of course, etiquette. This era and the people in it felt like there was a proper way to do things and that a certain level of decorum must be kept at all costs, in order to preserve their way of life.

Anyone who has studied history in school knows about the Civil War. It was, of course, fought over slavery. The South wanted to keep the slaves and the North wanted to free the slaves. The Civil War was unique in another way too. Most wars are fought with soldiers who are rough and tough, ready to take on the elements, and battle to the death for their cause. The Civil War was that too, but the men of the South during the Civil War Era, were part of an era of the southern belles and southern gentlemen. This was an era when a type of lifestyle was borrowed from the English countryside, and basically transplanted into the American south. The lifestyle included a glorification of elegant horse riding, hunting, and of course, etiquette. This era and the people in it felt like there was a proper way to do things and that a certain level of decorum must be kept at all costs, in order to preserve their way of life.

Tobacco played the central role in defining social class, local politics, and the labor system. In fact, it shaped the entire life of the region, and in doing so, actually shaped the Civil War. While the Civil War was a war, somehow the men of the South who fought in it felt like it needed to have that high level of decorum and decency. Tradition needed to be kept and carried on and while they knew that they were fighting a war, I’m not entirely sure that they understand that there would be, by necessity, loss of life and loss of that decorum and etiquette. For the men of the South especially, the Civil War was one of the most devastating events to challenge their way of life. This was also the most devastating event ever to occur on North American soil. While the loss of life was great, and in fact the Civil War caused more Americans to lose their lives than both World War I and World War II combined, the people of the South lost much of that “British Countryside” lifestyle that they thought so essential…and afterward, they didn’t quite know how to recover from that. The Confederate Army wanted to separate from the Union and maintain slavery, and the fight to combat that notion didn’t end until 1865. The differing ideas were a cause for rift long after the war was over.

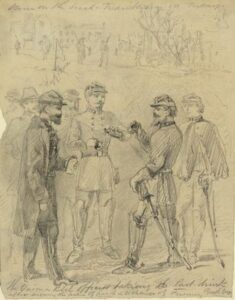

Nevertheless, despite the high stakes, the American soldiers from both sides still had several unofficial truces. Wars are usually long and tedious, and sometimes the men just needed to stop the fighting for a short time and try to be human again. Although these unofficial truces or ceasefires were usually frowned upon by military superiors, the men on either side would frequently call truces at the frontlines so Union and Confederate soldiers could chat, share information, and trade smokes. Imagine that…as the fighting is heavy, someone yells, “Wait…Smoke Break!!” Then both sides would stop shooting, walk out to the middle of te battlefield, and everyone would light a cigarette. I’m sure that’s not exactly how it happened, but they did actually hold such unofficial truces at times.

Nevertheless, despite the high stakes, the American soldiers from both sides still had several unofficial truces. Wars are usually long and tedious, and sometimes the men just needed to stop the fighting for a short time and try to be human again. Although these unofficial truces or ceasefires were usually frowned upon by military superiors, the men on either side would frequently call truces at the frontlines so Union and Confederate soldiers could chat, share information, and trade smokes. Imagine that…as the fighting is heavy, someone yells, “Wait…Smoke Break!!” Then both sides would stop shooting, walk out to the middle of te battlefield, and everyone would light a cigarette. I’m sure that’s not exactly how it happened, but they did actually hold such unofficial truces at times.

War is a really horrific thing for soldiers to go through, and closure comes in different forms for different soldiers. Returning to the battlefield is a way to find closure for many veterans. It is also a way for solders to keep the friendships they made at a time when their life depended on their fellow soldiers. Countless numbers of men have returned to places like the beaches of Normandy, France to see that place again, where so many lost their lives. Some soldiers didn’t leave the place they fought in their war. Vietnam was that way to a degree.

War is a really horrific thing for soldiers to go through, and closure comes in different forms for different soldiers. Returning to the battlefield is a way to find closure for many veterans. It is also a way for solders to keep the friendships they made at a time when their life depended on their fellow soldiers. Countless numbers of men have returned to places like the beaches of Normandy, France to see that place again, where so many lost their lives. Some soldiers didn’t leave the place they fought in their war. Vietnam was that way to a degree.

The Civil War was unique in that when the veterans decided to have their reunion, they wanted to, of course renew old friendships with those they shared a common bond, but they also wanted to make their reunion a way to bring the north and south back together again. The Gettysburg, Pennsylvania reunion was the largest of these events, and so made headline news around the world. The event took place in 1913 at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The Civil War was unique in that all participants were citizens of the United States. Brother fought against brother, and family members against family members. The reunion was a chance to repair those horribly broken relationships for all the men who were still alive at the reunion, which was held on the 50th anniversary of the battle. General H.S. Huidekoper, a Gettysburg Veteran of the 150th PA., was the man behind the idea of making it a gathering of both Northern and Southern Veterans on the 50th Anniversary of the battle. With the state of Pennsylvania, acting as host, $400,000 was set aside to finance the event. The Federal Government added $195,000 and the volunteer services of 1,500 officers and enlisted men. The event was five years in the planning, with Veteran groups throughout the nation helping to make it happen.

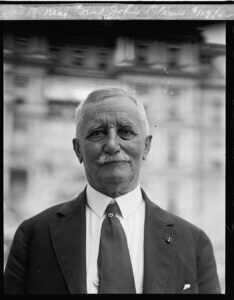

The Veterans who were still alive were aging, and because of the reunion, they were able not only to renew the friendships they had, but new friendships were born, and old wounds healed as well. The youngest Veteran, Colonel John C. Clem (known as the Shiloh drummer boy), was 62 years old. The oldest Veteran was 112 years of age. A total of 55,000 veterans attended the event, representing the half million living Confederate and Union Veterans. Of the 55,000 men, 22,103 came from Pennsylvania, and of those, 303 were Confederate. The smallest delegation came from New Mexico…one, a Union Veteran.

The event…one I wish I could have seen, saw over 5,000 tents, covering 280 acres in the middle of the battlefield, where so many had lost their lives. It was almost as if they were there too…giving their approval. Distinguished guests had come to give speeches and presentations. General Daniel Sickles, representing the III Corps at Gettysburg where he lost his leg, was the only corps commander present. On behalf of the battle leaders were the daughter of General Meade and the grandchildren of Generals Longstreet, A.P. Hill and Pickett.

The reunion lasted a full week. The men ate well and swapped stories, cried and laughed. In all 688,000 meals were served by two thousand cooks and helpers. Amazingly and considering the age and health of the Veterans, along with the hot, sultry weather, there were only nine Veterans who did not survive the week, a number well below the normal mortality rate for that day. Perhaps it was the exhilaration of the joining of old friends, reliving days of their youth, hearing the infamous Rebel Yell resound across the battlefield, or reenacting Pickett’s charge to have the Stars and Bars meet the trefoil of Hancock’s II Corps once more that had lengthened their lives.

In the most stunning moment of the event…on the fourth of July at high noon, a great silence fell over the battlefield, as the church bells began to toll. Buglers of the blue and gray prepared to play the mournful tune of Taps one last time. The guns of Gettysburg shook the ground, signaling the end of the weeklong event. When I visited Gettysburg many years later, I was surprised by exactly how that place felt. You could feel the atmosphere there all those years later. It is hallowed ground. You feel like you should whisper…or better yet just be silent. I have never felt that way before, or since.

And though many eloquent speeches were given at Gettysburg that week, none expressed what these Veterans took away from this experience better than a scene witnessed at the train station: “Nearly all of the men had said their good-byes and headed for home. On the station platform a former Union soldier from Oregon and a Louisiana Confederate were taking leave of each other. They shook hands and embraced, but neither seemed

able to find the words to express his feelings. Then an idea seemed to strike both men at once. In a simple act, which seemed to say everything they felt the pair took off their uniforms and exchanged them. The Yankee went home in Rebel gray, the Confederate in Union blue.” The above quote is an excerpt from “Gettysburg: The 50th Anniversary Encampment,” by Abbott M. Gibney, Civil War Times Illustrated, October 1970.

able to find the words to express his feelings. Then an idea seemed to strike both men at once. In a simple act, which seemed to say everything they felt the pair took off their uniforms and exchanged them. The Yankee went home in Rebel gray, the Confederate in Union blue.” The above quote is an excerpt from “Gettysburg: The 50th Anniversary Encampment,” by Abbott M. Gibney, Civil War Times Illustrated, October 1970.

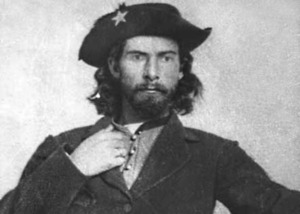

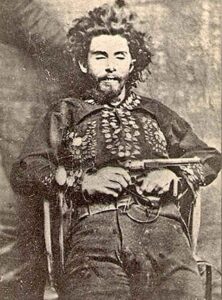

William T Anderson’s life was always rather a violent one, but it escalated when his sister died while in the custody of the Union soldiers during the Civil War. Anderson was born around 1840 in Hopkins County, Kentucky, to William and Martha Anderson. His siblings were Jim, Ellis, Mary, Josephine, and Martha. His schoolmates recalled him as a well-behaved, reserved child, so they might be surprised to see how he ended up. Anderson began to support himself early on, by stealing and selling horses in 1862. After a Union loyalist judge killed his father, Anderson killed the judge and fled to Missouri. He was always one to exact revenge for anything in which he felt that he or his family were wronged. In Missouri, he robbed travelers and killed several Union soldiers.

William T Anderson’s life was always rather a violent one, but it escalated when his sister died while in the custody of the Union soldiers during the Civil War. Anderson was born around 1840 in Hopkins County, Kentucky, to William and Martha Anderson. His siblings were Jim, Ellis, Mary, Josephine, and Martha. His schoolmates recalled him as a well-behaved, reserved child, so they might be surprised to see how he ended up. Anderson began to support himself early on, by stealing and selling horses in 1862. After a Union loyalist judge killed his father, Anderson killed the judge and fled to Missouri. He was always one to exact revenge for anything in which he felt that he or his family were wronged. In Missouri, he robbed travelers and killed several Union soldiers.

Anderson became a guerrilla, when his family was living in Council Grove, Territory of Kansas at the start of the Civil War. After William Quantrill’s raid on Aubry, Kansas on March 7, 1862, a Federal company from Olathe, Kansas sent a patrol from Company D, Eighth Kansas Jayhawker Regiment to investigate. Their mission was to seek out Southern sympathizers living nearby, who might be accused of aiding the raiders. Anderson’s father and uncle were named as such, and when the Jayhawker company arrived at the Anderson farm on March 11th, William and his younger brother Jim were delivering 15 head of cattle to the US commissary agent at Fort Leavenworth. When the brothers returned to their farm, they found their father and uncle hanged in retaliation, their home burned to the ground, and all their possessions stolen. It was an act of war in their minds, because the men had no chance to defend themselves. Two days later Bill and his brother Jim were both riding with Quantrill’s Raiders, a group of Confederate guerrillas operating along the Kansas–Missouri border. Anderson moved his sisters from Kansas, and for a year they lived at various places stopping finally with the Mundy family on the Missouri side of the line near Little Santa Fe. When asked why he joined Quantrill, Anderson replied by saying, “I have chosen guerrilla warfare to revenge myself for wrongs that I could not honorable revenge otherwise. I lived in Kansas when this war commenced. Because I would not fight the people of Missouri, my native State, the Yankees sought my life but failed to get me. [They] revenged themselves by murdering my father, [and] destroying all my property.”

Anderson became a skilled bushwhacker and quickly earned the trust of the group’s leaders, William Quantrill and George M Todd. It was his bushwhacking skills that ultimately marked him as a dangerous man…and eventually led the Union to imprison his sisters. Then, after a building collapse in the makeshift jail in Kansas City, Missouri, left one of his sisters dead, while in custody and the others permanently maimed, Anderson devoted himself to revenge. He took a leading role in the Lawrence Massacre and later took part in the Battle of Baxter Springs, both in 1863. He later satisfied his revenge by hijacking a train full of Union troops and slaughtering 24 of them, thus giving him the name “Bloody Bill” Anderson.

By 1863, all Bill had left was a brother and two sisters, who had miraculously survived the August 13 Union jail collapse in Kansas City. The collapse wasn’t an accident. Union guards from the 9th Kansas Jayhawker Regiment, serving as provost guards in town, intentionally collapsed a three-story brick building on a number of young Southern female prisoners. Fourteen-year-old Josephine Anderson was killed in the collapse. Bill’s ten-year-old sister Martha’s legs were horribly crushed crippling her for life, and his sixteen-year-old sister Mary suffered serious back injuries and facial lacerations. Both girls would carry their physical and emotional scars for the rest of their lives. War is an ugly thing, and unfortunately, sometimes unscrupulous people do things  they shouldn’t. The atrocity at the jail was a war crime and should have been punished as such, but I suppose that didn’t justify the murders that followed, because there was no proof that those murdered were involved in any way.

they shouldn’t. The atrocity at the jail was a war crime and should have been punished as such, but I suppose that didn’t justify the murders that followed, because there was no proof that those murdered were involved in any way.

Union military leaders ordered Lieutenant Colonel Samuel P Cox to kill Anderson and provided him with a group of experienced soldiers. A local woman saw Anderson soon after he left Glasgow and told Cox where he was. On October 26, 1864, Cox pursued Anderson’s group with 150 men and engaged them in a battle called the Skirmish at Albany, Missouri. Anderson and his men charged the Union forces, killing five or six of them, but turned back under heavy fire. Only Anderson and one other man, the son of a Confederate general, continued to charge after the others had retreated. Anderson was hit by a bullet behind an ear, which most likely killed him instantly. Four other guerrillas were killed in the attack as well. The victory made a hero of Cox and led to his promotion.

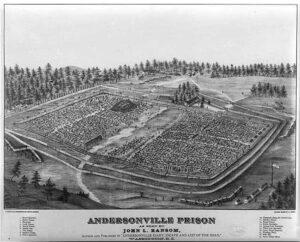

Andersonville POW camp was a Civil War era POW camp that was heavily fortified. It was run by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes when the war was over. The trial was presided over by Union General Lew Wallace and featured chief Judge Advocate General (JAG) prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman. The prison is located near Andersonville, Georgia, and today is a national historic site that is also known as Camp Sumpter. To me, its design had a somewhat unusual layout in that it had what is called a “Dead Line”. Some people might know what that is, but any prisoner who dared to tough it, much less try to cross it, found out very quickly what it was, because they were shot instantly…no questions asked. For that reason, prisoners rarely escaped from Andersonville Prison. The “dead line” was set up by the Confederate forces guarding the prison, to assist in prisoner control. The prison operated between February 25, 1864, and May 9, 1864. During that time, a total of 4,588 patients visited the Andersonville prison hospital, and 1,026 never left there alive.

Andersonville POW camp was a Civil War era POW camp that was heavily fortified. It was run by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes when the war was over. The trial was presided over by Union General Lew Wallace and featured chief Judge Advocate General (JAG) prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman. The prison is located near Andersonville, Georgia, and today is a national historic site that is also known as Camp Sumpter. To me, its design had a somewhat unusual layout in that it had what is called a “Dead Line”. Some people might know what that is, but any prisoner who dared to tough it, much less try to cross it, found out very quickly what it was, because they were shot instantly…no questions asked. For that reason, prisoners rarely escaped from Andersonville Prison. The “dead line” was set up by the Confederate forces guarding the prison, to assist in prisoner control. The prison operated between February 25, 1864, and May 9, 1864. During that time, a total of 4,588 patients visited the Andersonville prison hospital, and 1,026 never left there alive.

According to former prisoner, enlisted soldier John Levi Maile, “It consisted of a narrow strip of board nailed to a row of stakes, about four feet high.” The “dead line” completely encircled Andersonville. Soldiers were told to “shoot any prisoner who touches the ‘dead line'” “It was the standing order to the guards,” Maile explained. “A sick prisoner inadvertently placing his hand on the “dead line” for support… or anyone touching it with suicidal intent, would be instantly shot at, the scattering balls usually striking other than the one aimed at.” It was a risk the prisoners took if they chose to be anywhere near the “dead line” at all. Prisoner Prescott Tracy worked as a clerk in the Andersonville hospital. He said, “I have seen one hundred and fifty bodies waiting passage to the “dead house,” to be buried with those who died in hospital. The average of deaths through the earlier months was thirty a day; at the time I left, the average was over one hundred and thirty, and one day the record showed one hundred and forty-six.” The major threats in the prison camp were diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy.

A sergeant major in the 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, Robert H. Kellogg what he saw when he entered the camp as a prisoner on May 2, 1864, “As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect…stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. “Can this be hell?” “God protect us!” and all thought that he alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place. In the center of the whole was a swamp, occupying about three or four acres of the narrowed limits, and a part of this marshy place had been used by the prisoners as a sink, and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating. The ground allotted to our ninety was near the edge of this plague-spot, and how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then.”

After hearing the accounts of men who had the misfortune of being incarcerated in this horrific POW camp, I

wondered if there might have been some changes had the camp been run in more modern times. Of course, there is no guarantee of that, since there has been mistreatment of prisoners-of-war in all wars, and the treatment ultimately falls on the people running the camp and the soldiers monitoring the prisoners. It is, however, a sad state of affairs when prisoners are starved, beaten, frozen, and otherwise mistreated in these camps. The point is to hold them, not murder them.

wondered if there might have been some changes had the camp been run in more modern times. Of course, there is no guarantee of that, since there has been mistreatment of prisoners-of-war in all wars, and the treatment ultimately falls on the people running the camp and the soldiers monitoring the prisoners. It is, however, a sad state of affairs when prisoners are starved, beaten, frozen, and otherwise mistreated in these camps. The point is to hold them, not murder them.

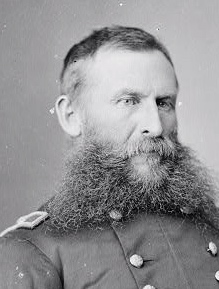

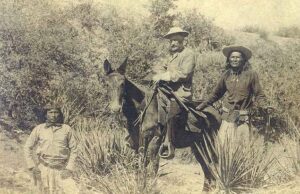

Not every great military hero was at the top of their class at military school. George Crook graduated 38th out of a class of 43 from the United States Military Academy in 1852. Crook was born to Thomas and Elizabeth Matthews Crook on a farm near Taylorsville, Montgomery County, Ohio (near Dayton). While his classroom career was not exemplary, he was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook Nantan Lupan, which means “Chief Wolf.”

Not every great military hero was at the top of their class at military school. George Crook graduated 38th out of a class of 43 from the United States Military Academy in 1852. Crook was born to Thomas and Elizabeth Matthews Crook on a farm near Taylorsville, Montgomery County, Ohio (near Dayton). While his classroom career was not exemplary, he was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook Nantan Lupan, which means “Chief Wolf.”

Crook was commissioned in the 4th Infantry and was first stationed in Northern California, until the outbreak of the Civil War. He was appointed colonel of the 36th Ohio Infantry and they were sent immediately to western Virginia, on September 12, 1861. He was promoted to brigadier general on September 7, 1862…less than a year later. He was put in command of a brigade of regiments from Ohio during the battles of South Mountain and Antietam, both part of the Maryland Campaign. Following that campaign, Crook was given command of a cavalry division in the Army of the Cumberland under General George H Thomas. He commanded that division through the Battle of Chickamauga. Crook was sent back to western Virginia and took part in General Ulysses S Grant’s spring campaign in the spring of 1864. During the campaign, Crook successfully commanded his brigade to victory against Confederate General A G Jenkins at the Battle of Cloyd’s Mountain. Crook was given command of the Department of Western Virginia which later became the VIII Corps under General Philip Sheridan, in August of 1864. Crook commanded his men throughout many of the battles of the Valley Campaign of 1864, including the battles of Third Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, and Cedar Creek. Crook was promoted to major general on October 21, 1864 and returned to the command of his department in Cumberland, Maryland. On February 21, 1865, while located in Cumberland Maryland, General Crook along with General Benjamin F Kelley were captured by a group of Confederate partisans under the command of Captain Jesse McNeill. On March 20, 1865, Crook was freed and placed in charge of a division of cavalry in the Army of the Potomac. He commanded his division until the surrender at Appomattox Court House.

Crook fought successful campaigns during the Indian wars, against several tribes, but later went on to speak  out against the unjust treatment of his former Indian adversaries. Crook was considered the Army’s preeminent Indian fighter during the Indian Wars. Even the Indians respected him. He was known to use two Apache scouts, Dutchy and Alchesay in his travels during the Indian Wars as well as his favorite mule, Apache. He died suddenly in Chicago in 1890 while serving as commander of the Military Division of the Missouri. Crook was originally buried in Oakland, Maryland, but in 1898, his remains were transported to Arlington National Cemetery, where he was reinterred. Red Cloud, a war chief of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux), said of him, “He, at least, never lied to us. His words gave us hope.” It was a great tribute.

out against the unjust treatment of his former Indian adversaries. Crook was considered the Army’s preeminent Indian fighter during the Indian Wars. Even the Indians respected him. He was known to use two Apache scouts, Dutchy and Alchesay in his travels during the Indian Wars as well as his favorite mule, Apache. He died suddenly in Chicago in 1890 while serving as commander of the Military Division of the Missouri. Crook was originally buried in Oakland, Maryland, but in 1898, his remains were transported to Arlington National Cemetery, where he was reinterred. Red Cloud, a war chief of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux), said of him, “He, at least, never lied to us. His words gave us hope.” It was a great tribute.

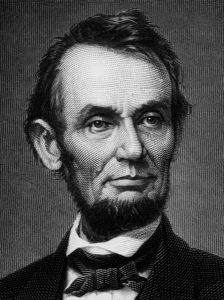

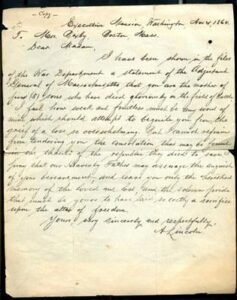

The hardest part about being a commander in any war situation is that moment when you have to tell a soldier’s family that they have been killed in action. It’s even easier to tell them that their soldier is missing, because at least then they have hope. The only thing that could possibly be harder than telling a soldiers family that they have been killed is to tell sibling soldiers’ family that they have been killed. That is the lot that fell to President Abraham Lincoln, according to legend, on November 21, 1864, except it came to him in spades. On that day, Lincoln composed a letter to Lydia Bixby, a widow and mother of five men, all of whom had been killed in the Civil War. It was a completely tragic state of affairs, and so made national news when a copy of the letter was published in the Boston Evening Transcript on November 25. It was signed by “Abraham Lincoln.” Oddly, the original letter has never been found, so it continues to be “legend” to this day.

The hardest part about being a commander in any war situation is that moment when you have to tell a soldier’s family that they have been killed in action. It’s even easier to tell them that their soldier is missing, because at least then they have hope. The only thing that could possibly be harder than telling a soldiers family that they have been killed is to tell sibling soldiers’ family that they have been killed. That is the lot that fell to President Abraham Lincoln, according to legend, on November 21, 1864, except it came to him in spades. On that day, Lincoln composed a letter to Lydia Bixby, a widow and mother of five men, all of whom had been killed in the Civil War. It was a completely tragic state of affairs, and so made national news when a copy of the letter was published in the Boston Evening Transcript on November 25. It was signed by “Abraham Lincoln.” Oddly, the original letter has never been found, so it continues to be “legend” to this day.

After expressing his condolences to Mrs Bixby on the death of her five sons, who had fought to preserve the Union in the Civil War, Lincoln goes on to express his regrets on how “weak and fruitless must be any words of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming.” He then continued with a prayer that “our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement [and leave you] the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours, to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of Freedom.”

Historians continue to debate the authorship of the letter, and the authenticity of copies printed between 1864 and 1891. Nevertheless, at that time, copies of presidential messages were often published and then sold as souvenirs. Many historians and archivists agree that the original letter was probably written by Lincoln’s secretary, John Hay. As to Mrs Bixby’s loss, scholars have since discovered that only two of her sons actually died fighting during the Civil War. A third was honorably discharged and a fourth was dishonorably thrown out of the Army. The fifth son’s fate is unknown, but it is assumed that he deserted or died in a Confederate prison camp. The facts in this case seem to show that sometimes Presidents are given misinformation, resulting in heartbreaking mistakes. If Mrs Bixby did receive this letter, it is my opinion that she quite likely fainted on the  spot, and then to find out later that the president had been given wrong information that caused him, gentle man that he was, to feel the need to write this particular letter himself, rather than letting the commanding officer be the bearer of such bad news.

spot, and then to find out later that the president had been given wrong information that caused him, gentle man that he was, to feel the need to write this particular letter himself, rather than letting the commanding officer be the bearer of such bad news.

I’m sure that upon finding that there had been an error, President Lincoln was appropriately appalled, but at that point there was not much to do about it. The letter had been sent, and to bring up the additional facts, especially the son that was thrown out of the army, would have only made matters worse. In addition, they did not know where the missing son was, and possibly didn’t know for sure where the others were either, so it made sense to leave well enough alone. Still, I’m sure their mother would like to have known where her sons really were. While this situation was possibly, or at least partially, an awful mistake, it is still the hardest part of the job of commander, and one that is usually felt very deeply by those who have had to write such a letter.

When we think of our mail carriers or even couriers, we generally think of someone who is mild mannered, and easy to get along with. Or some of us might think of someone who is lazy and slow, but we don’t often think of someone with “the temperament of a grizzly bear” and a quick hand on the draw. And if we do think of someone like that, we almost never think of it being a woman. Nevertheless, Stagecoach driver Mary Fields was one tough cookie, but it would be her devotion to her community that made her a legend across the Wild West.

When we think of our mail carriers or even couriers, we generally think of someone who is mild mannered, and easy to get along with. Or some of us might think of someone who is lazy and slow, but we don’t often think of someone with “the temperament of a grizzly bear” and a quick hand on the draw. And if we do think of someone like that, we almost never think of it being a woman. Nevertheless, Stagecoach driver Mary Fields was one tough cookie, but it would be her devotion to her community that made her a legend across the Wild West.

Sitting aloft on a stagecoach pulled by a team of horses, Fields covered over 300 miles every week to deliver mail across the West. She was not a petite woman, but rather she stood six feet tall. Fields kept a revolver and a rifle on her person at all times, and even when she wasn’t on the road, she was still a tough lady. When she was off duty, this postwoman of the Wild West was usually seen at the saloon or smoking a cigar. Fields was the first black woman to ride for the US Postal Service, and she wasn’t just tough, but she was one of a kind. She wasn’t a typical girly girl of the Wild West, but she was very special. Fields was a woman of grit.

Fields was born a slave in 1832, and according to some biographers, her mother was a house slave and her father a field slave. When Fields was in her 30s, she became a free woman following the Civil War. Once she was freed, Fields left Tennessee, and headed for Mississippi where she worked as a maid on the steamboat Robert E Lee. She later took a job as a servant in the home of Judge Edmund Dunne in Ohio. While she worked for the judge, she was introduced to his sister, Mother Amadeus, who was the Mother Superior of the Ursuline Convent in Toledo. The Mother Superior brought Fields on to work at the convent as a groundskeeper, but that job didn’t go well. When one sister asked Fields about her journey to Toledo, Fields replied that she needed “a good cigar and a drink.” I’m sure that a woman wanting a cigar and a drink in a convent probably wasn’t your average situation. One of the other nuns complained, “God help anyone who walked on the lawn after Mary had cut it.” In addition, the fiery groundskeeper with a “difficult” nature even loudly complained about her pay.

Then, in 1885, Fields left Ohio behind to travel west to Saint Peter’s Convent in the wilds of Montana where Mother Amadeus had established a children’s boarding school. The Mother Superior had fallen ill with pneumonia. Her choice of a caregiver…Fields, so she personally called for Fields to serve the nuns and nurse her back to health. Fields decided to settle in at the new convent after Mother Amadeus’ recovery. At the convent, Fields was given a position for which she was far better suited…the convent’s wagon team, hauling supplies. In addition to hauling supplies, Fields transported visitors to and from the train station. She was very serious about her job, once guarding the supplies for an entire night, single-handedly fending off a wolf pack that had spooked the horses, causing the wagon to flip.

While Fields loves working with that nuns, things were not always smooth sailing. When she wasn’t assisting the nuns and students and seeing to the chickens and vegetables on the Ursuline Convent, Mary Fields could be found in the local saloons, getting into fistfights, and smoking cigars. She also trained with a revolver and rifle, earning a reputation as a crack shot. Her tough as nails temperament, would eventually be her undoing at the Convent. Fields got into a heated confrontation with a janitor at the convent. Because Fields and the Convent’s janitor had pulled guns on each other during the argument and Brondell had her removed from her position.

Mother Amadeus remained a strong ally to Fields, and so encouraged Fields to move to nearby Cascade, Montana, where she was the only black resident. At first, the nuns helped her start a restaurant, but it failed. In 1895, Mother Mary Amadeus helped Fields to apply for another job as a mail carrier for the US Postal Service. Now in her 60s, Mary Fields secured the position when she hitched a team of six horses to a postal  coach faster than any other applicant. She then began her daily, 17-mile trek from Cascade to Saint Peter’s. She was the second woman in US history to ride a mail route. She earned the nickname Stagecoach Mary while working as a star route carrier, protecting the mail from bandits. Fields rode her stagecoach to the train station to pick up mail and then delivered it on several routes, some of which were more than 40 miles. Fields drove over 300 miles each week to deliver the mail. When winter snow blocked the roads, an undaunted Fields threw a mail sack on her shoulder and walked over 30 miles wearing snowshoes. The people of Montana applauded Mary Fields for her commitment…and for her kindness.

coach faster than any other applicant. She then began her daily, 17-mile trek from Cascade to Saint Peter’s. She was the second woman in US history to ride a mail route. She earned the nickname Stagecoach Mary while working as a star route carrier, protecting the mail from bandits. Fields rode her stagecoach to the train station to pick up mail and then delivered it on several routes, some of which were more than 40 miles. Fields drove over 300 miles each week to deliver the mail. When winter snow blocked the roads, an undaunted Fields threw a mail sack on her shoulder and walked over 30 miles wearing snowshoes. The people of Montana applauded Mary Fields for her commitment…and for her kindness.

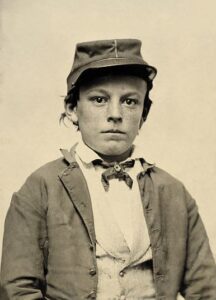

During the Civil War, military personnel was often short supply, and so, soldiers weren’t always adults. Sometimes, children enlisted, and sometimes they were “hired” on as messengers, scouts, and servants. They also might be hired on as musicians, such has drummers or buglers. On ships, children carried powder to fire the cannons, earning the nickname “powder monkeys.” In fact, one in five soldiers during the Civil War was under the age of 18.

During the Civil War, military personnel was often short supply, and so, soldiers weren’t always adults. Sometimes, children enlisted, and sometimes they were “hired” on as messengers, scouts, and servants. They also might be hired on as musicians, such has drummers or buglers. On ships, children carried powder to fire the cannons, earning the nickname “powder monkeys.” In fact, one in five soldiers during the Civil War was under the age of 18.

One such musician was Drummer John Joseph Klem. A popular legend suggests that Klem served as a drummer boy with the 22nd Michigan at the Battle of Shiloh. Legend has it that Klem came very near to losing his life when a fragment from a shrapnel shell crashed through his drum, knocking him unconscious and that subsequently his comrades, who found and rescued him from the battlefield, nicknamed Klem “Johnny Shiloh.” Klem slayed enemies in the Battle of Chickamauga…shooting a Confederate officer. Though Klem was only 10 years old, the Union made him a sergeant. Now imagine taking orders from a 10 year old sergeant.

Klem was born on August 13, 1851, to Roman and Magdalene Klem. His mother was killed crossing the railroad tracks when he was just 9 years old. As devastating as that was, his father’s second marriage was worse. John did not get along with his stepmother, and I suppose that could have contributed to his wanderlust spirit. He attended school in Newark, but often skipped school so he could drill as a drummer boy with a local unit…Company H, 3rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Like many people of that time, Klem felt strongly about the Civil War, but it was probably unusual for such a young boy to feel that way. Most likely the main factor the problems with his stepmother, making life at home unpleasant. His relatives joining up was probably another factor.

Motivating Klem was the fact that many of his relatives had enlisted in the army. He also deeply admired the president. In fact, he so admired President Lincoln that he changed his middle name to Lincoln. Because of his young age, recruiters turned Klem down when he tried to enlist. Several regiments passed through Newark on the way to the War. Klem immediately went to each and tried to join up, but each time he was turned down because of his age. He tried a new tactic, and traveled by train to try to enlist. That failed too, because he was always recognized by a friend or relative and sent home. Finally, Klem just ran away from home, to join the Army in 1861, at the age of 9. He finally got far enough away from home that they let him stay. Even then, he didn’t really enlist, because he was still too young. They allowed him to join the Michigan unit because they knew he would not give up until somebody let him join. When he offered his services as drummer to a company commander of the Third Ohio Volunteer Regiment, the captain looked him over and said he wasn’t “enlisting infants.” Johnny then tried to join the Twenty-second Michigan Regiment and was refused. Finally, he simply “went along with the regiment just the same, as a drummer boy, and though not on the muster roll, drew a soldier’s pay of thirteen dollars a month.” His pay was contributed by officers of the regiment.

At some point, Johnny Klem became Johnny Clem, although I am not sure just when. When Johnny Clem enlisted in the Army, legally or not, his intention was to stay. He might have been just a drummer boy at first, but when the shell hit his drum, he was not scared. Over the years of his service, he proved himself to be an invaluable member of the unit. He gained fame for his bravery on the battlefield, and became the youngest soldier ever to achieve the rank of sergeant, and I expect that record still stands. Clem retired from the United States Army in 1915, having attained the rank of brigadier general in the Quartermaster Corps. At the time of his retirement, he was the last veteran of the American Civil War still on duty in the US Armed Forces. By

special act of Congress on August 29, 1916, he was promoted to major general one year after his retirement.

special act of Congress on August 29, 1916, he was promoted to major general one year after his retirement.

Clem was married twice. He first married Anita Rosetta French in 1875, and after her passing in 1899, he met and married Bessie Sullivan of San Antonio in 1903. Sullivan was the daughter of a Confederate veteran. Clem enjoyed that fact, and often said, that he was “the most united American” alive. Clem was the father of three children. After his retirement in 1915, Clem lived in Washington DC before returning to San Antonio, Texas. Just as he had as a child on the battlefield, Clem defied the odd, living a long and healthy life. He died in San Antonio at the age of 85 on May 13, 1937, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia.