Caryn’s Thoughts

The Silver Bridge, over the Ohio River, was an eyebar-chain suspension bridge built in 1928 and named for the color of its aluminum paint. In structural engineering and construction, an eyebar is a straight bar, usually made of metal, with a hole or “eye” at each end for fixing to other components on the structure. Eyebars are used in structures such as bridges, in settings in which only tension, and never compression, is applied. Also referred to as “pin – and eyebar construction” in instances where pins are being used. The Silver Bridge carried US Route 35 over the Ohio River, connecting Point Pleasant, West Virginia, and Gallipolis, Ohio.

The Silver Bridge, over the Ohio River, was an eyebar-chain suspension bridge built in 1928 and named for the color of its aluminum paint. In structural engineering and construction, an eyebar is a straight bar, usually made of metal, with a hole or “eye” at each end for fixing to other components on the structure. Eyebars are used in structures such as bridges, in settings in which only tension, and never compression, is applied. Also referred to as “pin – and eyebar construction” in instances where pins are being used. The Silver Bridge carried US Route 35 over the Ohio River, connecting Point Pleasant, West Virginia, and Gallipolis, Ohio.

The problem with the original form of this structural engineering is that as it rusted or corroded, the eyebar-chain was weakened. It wasn’t an obvious weakening, and often presented in the form of a small crack. On December 15, 1967, the Silver Bridge collapsed under the weight of rush-hour traffic, resulting in the deaths of 46 people. Two of the victims were never found. In the ensuing investigation of the wreckage, it appeared that the cause of the collapse was the failure of a single eyebar in a suspension chain, due to a small defect that was just 0.1 inches deep. Analysis showed that the bridge was carrying much heavier loads than it had originally been designed for and had been poorly maintained.

The eyebars in the Silver Bridge were not redundant, as links were composed of only two bars each, of high-strength steel (more than twice the tensile strength of common mild steel), rather than a thick stack of thinner  bars of modest material strength “combed” together, as is usual for redundancy. With only two bars, the failure of one could impose excessive loading on the second, causing total failure…which would be unlikely if more bars were used. While a low-redundancy chain can be engineered to the design requirements, the safety is completely dependent upon correct, high-quality manufacturing, assembly, and maintenance. The bridge failure was due to a defect in a single link, eye-bar 330, on the north of the Ohio subsidiary chain, the first link below the top of the Ohio tower. A small crack was formed through fretting wear at the bearing, and grew through internal corrosion, a problem known as stress corrosion cracking.

bars of modest material strength “combed” together, as is usual for redundancy. With only two bars, the failure of one could impose excessive loading on the second, causing total failure…which would be unlikely if more bars were used. While a low-redundancy chain can be engineered to the design requirements, the safety is completely dependent upon correct, high-quality manufacturing, assembly, and maintenance. The bridge failure was due to a defect in a single link, eye-bar 330, on the north of the Ohio subsidiary chain, the first link below the top of the Ohio tower. A small crack was formed through fretting wear at the bearing, and grew through internal corrosion, a problem known as stress corrosion cracking.

The towers were “rocker” towers…a common European design, which allowed the bridge to respond to various live loads by a slight tipping of the supporting towers, which were parted at the deck level, rather than passing the suspension chain over a lubricated or tipping saddle, or by stressing the towers in bending. The towers required the chain on both sides for their support. A failure of any one link on either side, in any of the three chain spans, would result in the complete failure of the entire bridge. So many components that can so easily bring down a bridge…and no one knew.

At the time the Silver Bridge was built, a typical family automobile was the Ford Model T…weighing in at about 1,500 pounds. The maximum permitted truck gross weight was about 20,000 pounds. By contrast, at the time of the collapse, a typical family automobile weighed about 4,000 pounds and the large truck limit was 60,000 pounds or more. Bumper-to-bumper traffic jams on the bridge were also much more common, meaning that  during rush hour…several times a day, five days each week…there was significantly more stress on the bridge elements. The whole situation was a recipe for disaster, and that is exactly what happened on December 15, 1967. After the collapse, and the subsequent replacement of the Silver Bridge in 1969, a scale model of the original bridge was on display at the Point Pleasant River Museum. An archive of literature about the bridge was also kept there for public inspection. On the lower ground floor, the museum displayed an eyebar assembly from the original bridge. The museum closed July 1, 2018 due to significant fire damage. The future of the Silver Bridge exhibit is not known.

during rush hour…several times a day, five days each week…there was significantly more stress on the bridge elements. The whole situation was a recipe for disaster, and that is exactly what happened on December 15, 1967. After the collapse, and the subsequent replacement of the Silver Bridge in 1969, a scale model of the original bridge was on display at the Point Pleasant River Museum. An archive of literature about the bridge was also kept there for public inspection. On the lower ground floor, the museum displayed an eyebar assembly from the original bridge. The museum closed July 1, 2018 due to significant fire damage. The future of the Silver Bridge exhibit is not known.

It hardly seems possible that it can be two years ago already, that our family’s little Reece Balcerzak arrived in what was destined to be the beginning of a long time away from home for her parents, while they waited in Denver for their daughter to get strong enough to go home. It was a tough time, with an amazing ending. The little family came home victoriously with their precious girl. I guess that makes her middle name very much appropriate…Victoria, which means “victory” in Latin.

It hardly seems possible that it can be two years ago already, that our family’s little Reece Balcerzak arrived in what was destined to be the beginning of a long time away from home for her parents, while they waited in Denver for their daughter to get strong enough to go home. It was a tough time, with an amazing ending. The little family came home victoriously with their precious girl. I guess that makes her middle name very much appropriate…Victoria, which means “victory” in Latin.

Reece has so much more going for her than just her name, however. The little girl is not only a fighter, but she smiles more than just about anyone else I have ever seen. It is amazing that a little girl who has been through such a tough beginning can be so filled with joy, but then I guess that it was her parents and family who actually went through all that. Reece was just there, smiling at everyone through it all. Even as a tiny…and I really mean tiny…girl, she was filled with joy and always smiling. I find that so awesome!!

Since her very early arrival at 28 weeks into her mother, Katie’s pregnancy, Reece has been going at break-

neck speed to make up for the time she spend in the hospital in Denver. She is a very busy little girl. She never ceases to amaze all who know her. Her parents don’t really need much in the way of entertainment, because their daughter is really good at that. She is talking very well now, and chatters about the things that interest her, some of which we probably have no idea, because they are her happy things alone. Ahhh, the life of a child. To have such innocence, and such joy with the things around you. Reece has such a bright future ahead of her…so many things to learn and to explore. It will be exciting for us, her family, to watch this happy, smiley girl as she grows into the wonderful adult she will one day become. Keep smiling smiley girl. We love it. Today is Reece’s 2nd birthday. Happy birthday Reece. Have a great day!! We love you!!

neck speed to make up for the time she spend in the hospital in Denver. She is a very busy little girl. She never ceases to amaze all who know her. Her parents don’t really need much in the way of entertainment, because their daughter is really good at that. She is talking very well now, and chatters about the things that interest her, some of which we probably have no idea, because they are her happy things alone. Ahhh, the life of a child. To have such innocence, and such joy with the things around you. Reece has such a bright future ahead of her…so many things to learn and to explore. It will be exciting for us, her family, to watch this happy, smiley girl as she grows into the wonderful adult she will one day become. Keep smiling smiley girl. We love it. Today is Reece’s 2nd birthday. Happy birthday Reece. Have a great day!! We love you!!

There a number of ways for a soldier to be killed in a war, but we very seldom think of an avalanche as one of them. Nevertheless, on Dec 13, 1916, hundreds of Austrian soldiers in a barracks near Italy’s Mount Marmolada, were killed when a powerful avalanche came sweeping over them. As shocking as this seems, over a period of several days, avalanches in the Italian Alps killed an estimated 10,000 Austrian and Italian soldiers that December.

There a number of ways for a soldier to be killed in a war, but we very seldom think of an avalanche as one of them. Nevertheless, on Dec 13, 1916, hundreds of Austrian soldiers in a barracks near Italy’s Mount Marmolada, were killed when a powerful avalanche came sweeping over them. As shocking as this seems, over a period of several days, avalanches in the Italian Alps killed an estimated 10,000 Austrian and Italian soldiers that December.

The avalanches occurred as the Austrians and Italians were fighting World War I, but some witnesses claimed that the avalanches were purposefully caused to use as a weapon. I suppose that could be a possibility, but there was little evidence to prove that theory. Nevertheless, it is possible that avalanches could have been used as an unusual weapon of war at times during the war. It would make sense to use whatever was at your disposal, and the heavy snow could be an easy weapon of mass destruction.

The Italians entered World War I on the side of Britain, France, and Russia against Germany and Austria-Hungary in late April 1915. Over the next three years, a series of bloody battles between the Italian army and the Austrians occurred in the mountainous region along the Isonzo River near the Italian-Austrian border. The weather conditions in the mountains were often a bigger hazard than the actual fighting. An Austrian officer once said “The mountains in winter are more dangerous than the Italians.” This was certainly true in mid-December 1916 when heavy snowfall in the Alps created conditions ripe for avalanches. That left hundreds of Austrian troops, who were stationed in a barracks near the Gran Poz summit of Mount Marmolada, in particular danger. The camp there was well-placed to protect it from Italian attack, but it was vulnerable because it was situated directly under a mountain of unstable snow. The approximately 200,000 tons of snow, rock, and ice plunged down the mountain directly  onto the barracks on December 13, killing 300 soldiers. About 200 soldiers were pulled to safety, but of the dead, only a few bodies were recovered.

onto the barracks on December 13, killing 300 soldiers. About 200 soldiers were pulled to safety, but of the dead, only a few bodies were recovered.

As heavy snow and high winds continued over the next week, incidents like the one at Marmolada continued to happen with disturbing frequency. Entire regiments were lost in an instant. Some of the bodies of victims weren’t found until spring. The best estimate of the losses incurred that fateful December is somewhere between 9,000 and 10,000 soldiers…a shocking number for a weapon of mass destruction that we wouldn’t have ever expected to be a weapon of war at all.

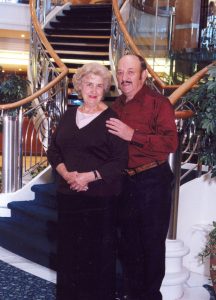

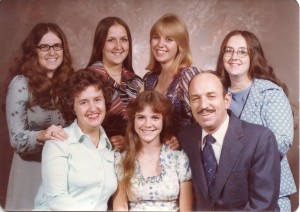

Few days make me dread writing my daily story, but then few days in my life have marked the beginning of such drastic change in my life either. It was December 12, 2007, twelve years ago, and my dad, Allen Spencer had been sick, or recovering for a little over two years, after being hit by Pancreatitis on October 1, 2005. My sisters and I had been caring for Dad, and our mom, Collene Spencer, who was diagnosed with Large Diffuse B-Cell Lymphoma in her brain in July of 2006. Mom’s tumor was gone quickly, and there were no other serious concerns with her, but Dad’s care required much more. Everything seemed to be going well, but Dad’s liver was giving out due to the intravenous feeding, something we couldn’t really see…or at least something we didn’t know to expect as a possibility.

Few days make me dread writing my daily story, but then few days in my life have marked the beginning of such drastic change in my life either. It was December 12, 2007, twelve years ago, and my dad, Allen Spencer had been sick, or recovering for a little over two years, after being hit by Pancreatitis on October 1, 2005. My sisters and I had been caring for Dad, and our mom, Collene Spencer, who was diagnosed with Large Diffuse B-Cell Lymphoma in her brain in July of 2006. Mom’s tumor was gone quickly, and there were no other serious concerns with her, but Dad’s care required much more. Everything seemed to be going well, but Dad’s liver was giving out due to the intravenous feeding, something we couldn’t really see…or at least something we didn’t know to expect as a possibility.

My dad had always been the “rock” of our family. None of us ever considered that he was not as strong as he once had been. We knew that no matter what was going on around us, Dad always knew what to do about any problem. It was a very comforting feeling in a family where he was the only original male. Of course, his daughters were married now, and a few grandsons had also been added to the mix, but for our childhood years, my sisters, Cheryl, Caryl, Alena, Allyn, and I were the kids they had, and so Dad was the only male. He was used to being the man with the answers, and we always looked to him when we needed those answers. It was difficult to see him in a state of weakness, but we would fight for his survival with all we had…never expecting to lose the fight.

With Dad’s passing on that awful December day, our world was forever changed. We were now going to need to take care of our mom, who needed us more than ever. While her health was ok, she didn’t drive anymore, and wasn’t as mobile as she had been before. We had promised Dad, we would take care of her, and as with Dad, we wouldn’t have it any other way for Mom. It wasn’t just the change is our care structure that changed either. Everything changed with Dad’s passing.

We had seriously never expected to live on this earth without our parents, and now that entire perspective had changed. We knew that very likely the day would come when both parents and our parents-in-law would be gone. We knew that we were going to be the leaders of our families. It was up to us to keep our families close, as Mom and Dad would have wanted us to do. There would now be great grandchildren who have never met their Great Grandpa Spencer, and later Great Grandma Spencer. It was up to us to tell the kids about their great grandparents, so they wouldn’t be forgotten. t was up to us to tell them that their Great Grandpa Spencer

was a World War II Veteran, who fought bravely for his country…to make sure that his legacy lived on. It is a big responsibility, and sometimes seems impossible, but we must, because our Dad showed us the way we should live, and we must now live it. There is no other choice. Twelve years ago today, my dad began his life in Heaven, and we miss him every day. We can’t wait until we will be reunited again. We love you Dad.

My nephew, Barry Schulenberg is a mechanic for the State of Wyoming. He comes from a long line of mechanics, in fact. Barry spent a lot of his young years hanging out with his grandpa, my father-in-law, Walt Schulenberg, who had spent most of life as a mechanic. Barry wanted nothing more than to be just like his grandpa. A large portion of Barry’s life has done just that. He is a mechanic, he lives in the country, and he’s married to his best friend, Kelli. He likes to travel, and enjoys Country music. Barry is a lot like his grandpa.

My nephew, Barry Schulenberg is a mechanic for the State of Wyoming. He comes from a long line of mechanics, in fact. Barry spent a lot of his young years hanging out with his grandpa, my father-in-law, Walt Schulenberg, who had spent most of life as a mechanic. Barry wanted nothing more than to be just like his grandpa. A large portion of Barry’s life has done just that. He is a mechanic, he lives in the country, and he’s married to his best friend, Kelli. He likes to travel, and enjoys Country music. Barry is a lot like his grandpa.

Barry is a hard working man. He works on his property in the country. In the summer months, Barry works to keep the brush around their place cut, so that there is less chance of fires getting to their house. It was a strategy that protected their home a few years ago, when a fire raged around them, but missed their house. The winter months find Barry, along with his uncles Bob and Ron Schulenberg, cutting wood to heat their homes. Barry and Kelli have a large incinerator-type of stove that heats their whole house. Barry can fill it up and it will heat the house for several hours.

Of course, life isn’t all about working. Barry and Kellie have lots of activities they like to do. They do a lot of traveling, and often attend concerts on their travels. And speaking of concerts, they have been to see a lot of country music stars. Their travels have taken them to a number of different states. They also love to hike. In

fact, that is probably the thing they like to do more than anything else. Unfortunately, in Wyoming, hiking is not a year-round activity, so they also go snow shoeing, skiing, and 4 wheeling…which can be done year round, of course. In addition to all of that, they regularly work out at one of the local gyms. All this is a great way to stay healthy. All in all, Barry and Kelli are two very active people, and that keeps them healthy. Today is Barry’s birthday. Happy birthday Barry!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

fact, that is probably the thing they like to do more than anything else. Unfortunately, in Wyoming, hiking is not a year-round activity, so they also go snow shoeing, skiing, and 4 wheeling…which can be done year round, of course. In addition to all of that, they regularly work out at one of the local gyms. All this is a great way to stay healthy. All in all, Barry and Kelli are two very active people, and that keeps them healthy. Today is Barry’s birthday. Happy birthday Barry!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

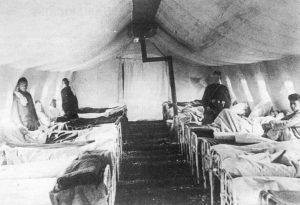

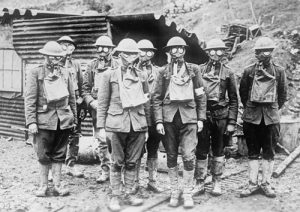

As nursing goes, I suppose you could say that World War I changed everything. War is an ugly business, and wounded men (and women these days) are just a part of the unavoidable side effects of it. As the upheaval of World War I changed the world, so the horrors of it, changed nursing.

As nursing goes, I suppose you could say that World War I changed everything. War is an ugly business, and wounded men (and women these days) are just a part of the unavoidable side effects of it. As the upheaval of World War I changed the world, so the horrors of it, changed nursing.

From 1914 to 1918, what was dubbed “the war to end all wars” in the innocence of the times, anyway…led to the mobilization of more than 70 million military personnel, including 60 million Europeans, making it one of the largest wars in history. As we know, it was hardly the war to end all wars, but it did change many of the things we had come to expect war to be. World War I was one of the deadliest conflicts in history. The death toll is staggering…estimated nine million combatants and seven million civilian deaths, as a direct result of the war. To add to that total, came the resulting genocides, as well as the 1918 influenza pandemic, which caused another 50 to 100 million deaths worldwide.

Now, just imagine being a nurse in those days. Of course, medical tents and hospitals were close to the perimeter of the fighting, to care for hurt soldiers quickly. This assured that the World War I nurses were witness to the conflict firsthand. I seriously doubt if any of them walked away from the war with less PTSD than the soldiers did. Many of them wrote about their involvement in diaries and letters that, similar to photographs from this time, offer insight into how they were personally impacted. The journals also include details about fighting, disease, and the hope that nurses and soldiers alike found in their darkest moments…if there could be any hope to be found.

It was in World War I that Germany introduced gas as a new form of aggression in 1915. It was in many ways the latest form of terrorism. To say that it was a different level of engagement seems an understatement. Gas devices became commonplace. They were worn anytime an air raid siren sounded, and some people wore them much of the time, as a precaution. The soldiers didn’t go anywhere without their gas mask. It was their life-line. Still, they were among the most feared elements of World War I.

“Sister Edith Appleton was a British nurse who served in France during World War I. She wrote about the soldiers stricken by gas and the adverse physical impacts they endured. The minimal immediate effects are tearing of the eyes, but subsequently, it causes build-up of fluid in the lungs, known as pulmonary edema, leading to death. It is estimated that as many as 85% of the 91,000 gas deaths in WWI were a result of phosgene or the related agent, diphosgene (trichloromethane chloroformate).”

Margaret Trevenen Arnold, a volunteer British Red Cross nurse in France in 1915 kept a diary of her time at Le Tréport and described “groans, and moans, and shouts, and half-dazed mutterings, and men with trephined heads suddenly sitting bolt upright… It was awful, and I really know now what [conflict] means.” These serious head injuries would most likely cause permanent brain damage for these men…if they survived at all.

Some hospital tents were eerily quiet, because the men in them were too sick to make a sound. Bandages were changed as often as every two hours, in an effort to ward off infection, and tourniquets to stop the bleeding until the soldier could be sent to surgery. Most of these field “hospitals” faced the same serious conditions…a lack of clean water and sterile surroundings. The nurses had to make due with what they had…and that often wasn’t much. Sometimes the lack of medicine became a major issue, especially when it came to anesthesia. Sometimes, the soldier had to simply force himself to remain calm, and steel himself to the inevitable pain of the surgery. These men had to place their faith in the doctors and nurses who cared for them, and they had not had time to even prepare for the need for surgery…let alone without anesthesia.

“Violet Gosset served on the Western Front from 1915 to 1919. While working at a hospital in Boulogne, France, Gosset kept notes about her experiences. She described a lack of supplies, overcrowded conditions, and scrapes that often resulted from a lack of adequate protection.”

“Helen Dare Boylston, an American nurse who served in France with the Harvard Unit medical team, had patients that spanned a wide range of age demographics. Some of the soldiers were just teenagers (“boys”), while others were in their 20s. However, Boylston recalled at least one soldier in his 60s (she called him “Dad”). Boylston saw the number of men in her care rise significantly in March 1918. At this time, she was sent…with two other nurses…to care for 500 soldiers. Boylston and her fellow nurses, including one named Ruth, quickly adapted to their conditions.”

Trench warfare was a shock to most of the soldiers. Still, most soldiers remained in good spirits. A part of nursing that might be considered a little different in the field hospitals is that the nurses are “in charge of” morale to a great degree. whether the men had Trench Foot, were sick, or wounded, they needed to have someone to lift their spirits. Who would have ever thought of nurses as morale boosters, but it was so.

Flu was widespread during World War I, even before the pandemic of 1918. After the pandemic began, things became critical. Now, nurses had to contend with treatment and prevention, in addition to other issues. One problem is that soldiers who ended up in medical tents and hospitals were often covered in mud, and flies frequently buzzed around them. Keeping germs at bay was next to impossible.

“Nurse Helen Dare Boylston was a keen observer of how soldiers reacted when they returned from the front, especially when they interacted with female nurses. She commented on the “fascinating game” of casual

romance that commonly played out in the midst of conflict-related stress.” This was probably one of the most unusual phenomena, because nurses are told not to get emotionally involved, and yet here it was exactly what was needed. Nursing has changed over the years, but never has it been so evident as in World War I. It was as if nurses were making it up as they went along…and maybe they were.

romance that commonly played out in the midst of conflict-related stress.” This was probably one of the most unusual phenomena, because nurses are told not to get emotionally involved, and yet here it was exactly what was needed. Nursing has changed over the years, but never has it been so evident as in World War I. It was as if nurses were making it up as they went along…and maybe they were.

These days, it seems we are all aware of what an emu is, probably due to the Liberty Mutual commercials that are out there, but in 1932 Australia, these were a nuisance bird. They were everywhere and they were not popular. In fact, they were running amok in the Campion district of Western Australia, and the public was very concerned. They had made several attempts to curb the growth of the emu population, including the Australian soldiers being armed with Lewis guns…leading the media to adopt the name “Emu War” when referring to the incident. While a number of the birds were killed, the emu population persisted and continued to cause crop destruction.

These days, it seems we are all aware of what an emu is, probably due to the Liberty Mutual commercials that are out there, but in 1932 Australia, these were a nuisance bird. They were everywhere and they were not popular. In fact, they were running amok in the Campion district of Western Australia, and the public was very concerned. They had made several attempts to curb the growth of the emu population, including the Australian soldiers being armed with Lewis guns…leading the media to adopt the name “Emu War” when referring to the incident. While a number of the birds were killed, the emu population persisted and continued to cause crop destruction.

After World War I ended, the Australian government gave land to large numbers of ex-soldiers from Australia and the UK. The purpose of the gift was to take up farming within Western Australia, often in areas that had been counterproductive. When the Great Depression hit in 1929, these farmers were encouraged to increase their wheat crops. The government promised assistance in the form of subsidies, but later failed to deliver. In spite of the recommendations and the promised subsidies, wheat prices continued to fall, and by October 1932 matters were becoming critical, with the farmers preparing to harvest the season’s crops and threatening to refuse to deliver the wheat.

To make matters, the area was hit with the arrival of as many as 20,000 emus. This is apparently an annual event as the emus regularly migrate after their breeding season, heading to the coast from the inland regions. With the cleared land and additional water supplies being made available for livestock by the Western Australian farmers, the emus decided that the farmlands were a good, and closer habitat, and they began to foray into farm territory, especially in the marginal farming land around Chandler and Walgoolan. The emus began to eat and spoil the crops. In addition, they left large gaps in fences where rabbits could enter and cause further destruction.

When the farmers relayed their concerns about the birds ravaging their crops, and a group of the ex-soldiers were sent to meet with the Minister of Defense, Sir George Pearce. Something had to be done. Having served in World War I, the soldiers-turned-settlers were well aware of the effectiveness of machine guns, and they requested their deployment to fight this new enemy. The minister readily agreed, although with conditions attached: the guns were to be used by military personnel, troop transport was to be financed by the Western Australian government, and the farmers would provide food, accommodation, and payment for the ammunition. The farmers agreed and Pearce also supported the deployment on the grounds that the birds would make good target practice, while some in the government viewed the operation as a way of being seen to be helping the Western Australian farmers, as a way of staving off the secession movement that was brewing.

Sir George Pearce, who was later referred to in Parliament, as the “Minister of the Emu War” by Senator James Dunn, ordered the army to selectively thin the nuisance emu population…by large numbers. The “war” was scheduled to begin in October 1932, under the command of Major G P W Meredith of the Seventh Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery. Meredith was supposed to use troops armed with two Lewis guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition, but the operation was delayed by a period of rainfall that caused the emus to scatter over a wider area. The rain finally stopped by November 2, 1932, and the troops were quickly deployed with orders to assist the farmers and, according to a newspaper account, to collect 100 emu skins so that their feathers could be used to make hats for light horsemen. On November 2nd, the men travelled to Campion, where some 50 emus were sighted. Unfortunately, when they got there, the birds were out of range of the guns. The local settlers attempted to herd the emus into an ambush, but the birds split into small groups and ran so that they were difficult to target. Nevertheless, while the first attack from the machine guns was ineffective due to the distance from the targets, a second round of gunfire was able to kill “a number” of birds. Later the same day, a small flock was encountered, and “perhaps a dozen” birds were killed.

The next significant event was on November 4th, when Meredith established an ambush near a local dam. More than 1,000 emus were spotted heading towards their position. This time the gunners waited until the birds were in close proximity before opening fire. The gun jammed after only twelve birds were killed and the rest scattered before any more could be shot. No more birds were sighted that day, so the decision was made to move further south, where the birds were “reported to be fairly tame.” The group had only limited success in spite of Meredith’s efforts. As the pursuit continued, it became apparent that “each pack seemed to have its own leader now…a big black-plumed bird which stands fully six feet high and keeps watch while his mates carry out their work of destruction and warns them of our approach.” In desperation, Meredith even went so far as to mount one of the guns on a truck. He was still ineffective, as the truck was unable to gain on the birds, and the ride was so rough that the gunner was unable to fire any shots, even if they had been able to get close. By November 8th, six days after the first attack, 2,500 rounds of ammunition had been fired. The number of birds killed is uncertain. One account estimates that it was 50 birds, but other accounts range from 200 to 500, the latter figure being provided by the settlers. Meredith’s official reported that there were no casualties among the men.

Summarizing the operation, ornithologist Dominic Serventy commented, “The machine-gunners’ dreams of point blank fire into serried masses of Emus were soon dissipated. The Emu command had evidently ordered guerrilla tactics, and its unwieldy army soon split up into innumerable small units that made use of the military equipment uneconomic. A crestfallen field force therefore withdrew from the combat area after about a month. On 8 November, members in the Australian House of Representatives discussed the operation. Following the negative coverage of the events in the local media, that included claims that “only a few” emus had died, Pearce withdrew the military personnel and the guns on 8 November.”

After the “Emu War” was over, Meredith compared the emus to Zulus and commented on the striking maneuverability of the emus, even while badly wounded. After the withdrawal of the military, the emu attacks on crops continued. Farmers again asked for support, citing the hot weather and drought that brought emus invading farms in the thousands. James Mitchell, the Premier of Western Australia lent his strong support to renewal of the military assistance. At the same time, a report from the Base Commander was issued that indicated 300 emus had been killed in the initial operation.

The killing continued periodically, with similar results. The Emu was just too fast, too aware, or too “lucky,” to be caught or killed. By December 1932, word of the Emu War had spread, reaching the United Kingdom.  Conservationists protested the cull as “extermination of the rare emu”. Dominic Serventy and Hubert Whittell, the eminent Australian ornithologists, described the “war” as “an attempt at the mass destruction of the birds”. Throughout 1930 and onward, the farmers tried exclusion barrier fencing as a means of keeping emus out of agricultural areas (in addition to other vermin, such as dingoes and rabbits). In November 1950, Hugh Leslie raised the issues of emus in federal parliament and urged Army Minister Josiah Francis to release a quantity of .303 ammunition from the army for the use of farmers. The minister approved the release of 500,000 rounds of ammunition. The emu continues to thrive today.

Conservationists protested the cull as “extermination of the rare emu”. Dominic Serventy and Hubert Whittell, the eminent Australian ornithologists, described the “war” as “an attempt at the mass destruction of the birds”. Throughout 1930 and onward, the farmers tried exclusion barrier fencing as a means of keeping emus out of agricultural areas (in addition to other vermin, such as dingoes and rabbits). In November 1950, Hugh Leslie raised the issues of emus in federal parliament and urged Army Minister Josiah Francis to release a quantity of .303 ammunition from the army for the use of farmers. The minister approved the release of 500,000 rounds of ammunition. The emu continues to thrive today.

My niece, Jessi Sawdon has a great sense of humor, and by that I don’t mean that she can tell a good joke once in a while, although, she can, but with Jessi it’s different than that. Jessi just likes to be silly. Even from her youngest days, she liked to tease her mom, my sister, Allyn Hadlock, by telling her that she (Jessi) was the mom. It went back and forth for a while, and then, Allyn would tell her, “Don’t you ever say I’m the mom.” Jessie, would instantly say…while pointing her finger up…not down…at her mom, “Don’t you ebber!!” How do you not laugh at this little 2 year old girl…bossing her mom around.

My niece, Jessi Sawdon has a great sense of humor, and by that I don’t mean that she can tell a good joke once in a while, although, she can, but with Jessi it’s different than that. Jessi just likes to be silly. Even from her youngest days, she liked to tease her mom, my sister, Allyn Hadlock, by telling her that she (Jessi) was the mom. It went back and forth for a while, and then, Allyn would tell her, “Don’t you ever say I’m the mom.” Jessie, would instantly say…while pointing her finger up…not down…at her mom, “Don’t you ebber!!” How do you not laugh at this little 2 year old girl…bossing her mom around.

While things like that were a god beginning to Jessi’s silliness, they were by no means the end. As a kid, she used to take pictures of her cousins that were at her grandmother, my mom, Collene Spencer’s house, and turn them around, or move them to the lowest spot, elevating her picture to the higher spot on the display, saying, “I’m Grandma’s favorite!!” She wasn’t being mean, but rather was teasing. A big smile on her face every time. We all laughed at her antics. When Jessi and her family would be visiting my mom and dad, Al Spencer, someone would tell her to ask Grandma something, and she would look right at her grandma and say, “Who’s Grandma?” My mom would laugh and laugh, as would everyone else. Jessi was always so quick witted and so random that you just never knew what to expect from her.

Jessi was known for having “name calling” sessions with her siblings. I’m sure that sounds terrible, but this was a competition…and they all participated, trying mot to laugh the whole time. They might call each other dummy. Her sister, Kellie Hadlock often calls Jessi…Jeffica McHaddlo, Jeffrey, Jeff, or just Re. Jessi in turn calls Kellie…Pie, and on National Pie Day, always wishes her youngest sister, “Happy Pie Day!!” Jessi and her sister, Lindsay Moore, both celebrate their “unbirthdays,” and idea they got from Alice in Wonderland. I guess you might as well have more than one birthday in a year…or maybe several, since every day that isn’t your birthday, is by definition, your unbirthday!! You never knew what Jessi might do. She has even been known to dance like a rag doll while riding in the car.

While Jessi, being the oldest, often had the upper hand in the teasing sessions, once in a while they got her

back. Her family took her to a local Mexican restaurant called Guadalajara for her birthday. When the family had the waiters sing “Happy Birthday” to Jessi, they crowned her with a sombrero and sang. Kellie tells me that is the only time she has ever seen her big sister embarrassed. I guess that once in a while, even the funniest among us can be “had!!” Hahahahahaha!! Today is Jessi’s real birthday. Happy birthday Jessi!! Pretend I crowned you with a sombrero!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

back. Her family took her to a local Mexican restaurant called Guadalajara for her birthday. When the family had the waiters sing “Happy Birthday” to Jessi, they crowned her with a sombrero and sang. Kellie tells me that is the only time she has ever seen her big sister embarrassed. I guess that once in a while, even the funniest among us can be “had!!” Hahahahahaha!! Today is Jessi’s real birthday. Happy birthday Jessi!! Pretend I crowned you with a sombrero!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Probably the most notable memorials of the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, is the Arizona Memorial, which floats atop the sunken ship USS Arizona, which sank during that attack, taking with it 1,177 men. In all, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, took the lives of 1998 navy personnel, 109 Marines, 233 army personnel and 48 civilians that were killed in that bombing which resulted in 2,402 soldiers killed and 1,282 military personnel and civilians wounded. Over half of the fatalities of that dreadful day occurred on the USS Arizona.

Probably the most notable memorials of the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, is the Arizona Memorial, which floats atop the sunken ship USS Arizona, which sank during that attack, taking with it 1,177 men. In all, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, took the lives of 1998 navy personnel, 109 Marines, 233 army personnel and 48 civilians that were killed in that bombing which resulted in 2,402 soldiers killed and 1,282 military personnel and civilians wounded. Over half of the fatalities of that dreadful day occurred on the USS Arizona.

The USS Arizona had one more situation that would make it unique…in a tragic way. There were 38 sets of brother stationed on the USS Arizona. The brothers totaled 79 men. Of these 79 brothers, 63 lost their lives that day. There were three sets of three brothers: the Beckers, the Dohertys, and the Murdocks. Only one of each of the sets of three survived. Of the 38 sets of brothers on the USS Arizona, 23 complete sets were lost. There was also a father/son set on the USS Arizona…both of whom were killed in the attack. This is in no way to say that any of the other people killed in the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7, 1941 were less important that these brothers or the father and son set, because they weren’t. Every person that served when out nation was brutally attacked that day, gave their lives for their country. The brothers serving was unusual, in that the military tries not to place siblings together,  lest they both be killed, but these men requested this. They liked having their brother there with them. I can understand that. Long months away from family can be very lonely.

lest they both be killed, but these men requested this. They liked having their brother there with them. I can understand that. Long months away from family can be very lonely.

The explosion and subsequent fires on the USS Arizona killed 1,177 sailors and marines instantly. The entire front portion of the ship was destroyed, because the fire burned everything in its path. To make matters worse, the fires continued for 2½ days, causing the bodies that were there to be cremated before anyone could located and removed. Out of a crew of 1,511 men on the USS Arizona, only 334 survived. Of the dead, only 107 were positively identified, due to the immense fire. The remaining 1,070 casualties fell into three categories: (1) Bodies that were never found; (2) Bodies that were removed from the ship during salvage operations and were severely dismembered or partially cremated that identification was impossible. DNA testing was unheard of in 1941. These bodies were placed in temporary mass graves, and later moved and reburied and marked as unknowns, at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl) in 1949; and (3) Bodies located in the aft (rear) portion of the ship. These remains could have been recovered, but were left in the ship due to their unidentifiable condition. The injuries to these bodies indicated that most of these crew members died from the concussion from the massive explosion.

Everyone of the people who lost their lives on December 7, 1941, at Pearl Harbor, were heroes. Their families were left to mourn their loss, mostly without the closure that can be found when there is a body to bury. The horrific attack marked the inevitable entrance of the United States into World War II, and if the Japanese thought they could beat the United States with this sneak attack, they soon found out just how wrong they were. They had awakened the “sleeping giant” and they would be sorry they did. Today we honor all those who dies at Pearl Harbor, but also, all who survived and went forward to avenge their fallen comrades. We will never forget their sacrifice. We are forever grateful.

Everyone of the people who lost their lives on December 7, 1941, at Pearl Harbor, were heroes. Their families were left to mourn their loss, mostly without the closure that can be found when there is a body to bury. The horrific attack marked the inevitable entrance of the United States into World War II, and if the Japanese thought they could beat the United States with this sneak attack, they soon found out just how wrong they were. They had awakened the “sleeping giant” and they would be sorry they did. Today we honor all those who dies at Pearl Harbor, but also, all who survived and went forward to avenge their fallen comrades. We will never forget their sacrifice. We are forever grateful.

The morning of December 6, 1945 found the United States Navy desperately searching the area known as the Bermuda Triangle for a group of planes. Flight 19 was a routine navigation and combat training exercise in TBM-type aircraft. The group had set out on December 5, 1945 at 2:10pm from Fort Lauderdale Naval Air Station. Their training would take them due east toward the Bermuda Triangle. Much mystery has surrounded the Bermuda Triangle, with ship and planes alike reporting navigation problems in the area, and some disappearing forever. I don’t exactly know what I believe about the Bermuda Triangle, but it is my opinion that there is a logical explanation for the events that have taken place there. Still, many of the lost planes and ship were never heard from again, and never located, so I don’t know.

The morning of December 6, 1945 found the United States Navy desperately searching the area known as the Bermuda Triangle for a group of planes. Flight 19 was a routine navigation and combat training exercise in TBM-type aircraft. The group had set out on December 5, 1945 at 2:10pm from Fort Lauderdale Naval Air Station. Their training would take them due east toward the Bermuda Triangle. Much mystery has surrounded the Bermuda Triangle, with ship and planes alike reporting navigation problems in the area, and some disappearing forever. I don’t exactly know what I believe about the Bermuda Triangle, but it is my opinion that there is a logical explanation for the events that have taken place there. Still, many of the lost planes and ship were never heard from again, and never located, so I don’t know.

Flight 19 consisted of five TBM Avenger torpedo bombers, all of which disappeared on December 5, 1945, during the overwater navigation training flight from Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale, Florida. In all, 14 airmen on the flight were lost, as were all 13 crew members of a PBM Mariner flying boat that was searching for the planes. It is assumed by professional investigators to have exploded in mid-air. Navy investigators could not determine the cause of the loss of Flight 19, but said the aircraft may have become disoriented and ditched in rough seas after running out of fuel. While that is logical, no debris was ever found, nor were the planes ever located, although some think they know where the planes are these days.

The assignment was called “Navigation problem No. 1,” which seems ironic in retrospect. The name was given before the planes experienced problems. “Navigation problem No. 1” was a combination of bombing and navigation, which other flights had completed or were scheduled to undertake that day. The leader for Flight 19 was United States Navy Lieutenant Charles Carroll Taylor who had about 2,500 flying hours, mostly in aircraft of this type, while his trainee pilots had 300 total, and 60 flight hours in the Avenger. Taylor had recently arrived from Naval Air Station Miami where he had also been a VTB instructor. The student pilots had recently completed other training missions in the area where the flight was to take place. They were United States Marine Captains Edward Joseph Powers and George William Stivers, United States Marine Second Lieutenant Forrest James Gerber and United States Navy Ensign Joseph Tipton Bossi. The callsigns for the flight started with ‘Fox Tair,’ or FT and the plane number.

Each aircraft was fully fueled, and during pre-flight checks it was discovered they were all missing clocks. Navigation of the route was intended to teach dead reckoning principles, which involved calculating among other things elapsed time. I suppose that if trained, a person could do that, but I don’t think I could. The apparent lack of timekeeping equipment was not a cause for concern as it was assumed each man had his own watch. Takeoff was scheduled for 13:45 local military time, but the late arrival of Taylor delayed departure until 14:10. The weather at NAS Fort Lauderdale was described as “favorable, sea state moderate to rough.” Taylor was supervising the mission, and a trainee pilot had the role of leader out front.

This exercise was called “Naval Air Station, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, navigation problem No. 1,” and involved three different legs. There should have actually been four flown. After take off, the planes flew on heading 091°, which is almost due east for 56 nautical miles, until they reached Hen and Chickens Shoals where low level bombing practice was carried out. The flight was to continue on that heading for another 67 nautical miles before turning onto a course of 346° for 73 nautical miles, in the process over-flying Grand Bahama island. The next scheduled turn was to a heading of 241° to fly 120 nautical miles at the end of which the exercise was completed and the Avengers turned left to return to NAS Fort Lauderdale.

Radio conversations between the pilots were overheard by base and other aircraft in the area. The practice bombing operation was carried out because at about 15:00 a pilot requested and was given permission to drop his last bomb. Forty minutes later thins began to go wrong, when another flight instructor, Lieutenant Robert F. Cox in FT-74, forming up with his group of students for the same mission, received an unidentified transmission. An unidentified crew member asked Powers, one of the students, for his compass reading. Powers replied: “I don’t know where we are. We must have got lost after that last turn.” Cox then transmitted; “This is FT-74, plane or boat calling ‘Powers’ please identify yourself so someone can help you.” The response after a few moments was a request from the others in the flight for suggestions. FT-74 tried again and a man identified as FT-28 (Taylor) came on. “FT-28, this is FT-74, what is your trouble?” “Both of my compasses are out”, Taylor replied, “and I am trying to find Fort Lauderdale, Florida. I am over land but it’s broken. I am sure I’m in the Keys but I don’t know how far down and I don’t know how to get to Fort Lauderdale.” As the weather deteriorated, radio contact became intermittent, and it was believed that the five aircraft were actually by that time more than 200 nautical miles out to sea east of the Florida peninsula. Taylor radioed “We’ll fly 270 degrees west until landfall or running out of gas.” The last known location of Flight 19 was 75 miles northeast of Cocoa, Florida.

Had Flight 19 actually been where Taylor believed it to be, landfall with the Florida coastline would have been reached in a matter of 10 to 20 minutes or less, depending on how far down they were. However, a later reconstruction of the incident showed that the islands visible to Taylor were probably the Bahamas, well northeast of the Keys, and that Flight 19 was exactly where it should have been. The board of investigation found that because of his belief that he was on a base course toward Florida, Taylor actually guided the flight further northeast and out to sea. The only problem I have with that idea is that they never found any debris, and never located the planes. Had they crashed into the ocean, they should have shown up somewhere.

In 1986, the wreckage of an Avenger was found off the Florida coast during the search for the wreckage of the Space Shuttle Challenger. Aviation archaeologist Jon Myhre raised the wreck from the ocean floor in 1990. He was convinced it was one of the missing planes, but positive identification could not be made. In 1991, the wreckage of five Avengers was discovered off the coast of Florida, but engine serial numbers revealed they  were not Flight 19. They had crashed on five different days all within 1.5 miles of each other. Records revealed that the various discovered aircraft, including the group of five, were declared either unfit for maintenance/repair or obsolete, and were simply disposed of at sea. Records also showed training accidents between 1942 and 1945 accounted for the loss of 95 aviation personnel from NAS Fort Lauderdale. In 1992, another expedition located scattered debris on the ocean floor, but nothing could be identified. In the last decade, searchers have been expanding their area to include farther east, into the Atlantic Ocean, but the remains of Flight 19 have still never been confirmed found.

were not Flight 19. They had crashed on five different days all within 1.5 miles of each other. Records revealed that the various discovered aircraft, including the group of five, were declared either unfit for maintenance/repair or obsolete, and were simply disposed of at sea. Records also showed training accidents between 1942 and 1945 accounted for the loss of 95 aviation personnel from NAS Fort Lauderdale. In 1992, another expedition located scattered debris on the ocean floor, but nothing could be identified. In the last decade, searchers have been expanding their area to include farther east, into the Atlantic Ocean, but the remains of Flight 19 have still never been confirmed found.