amputation

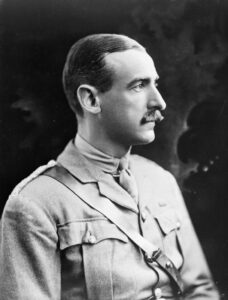

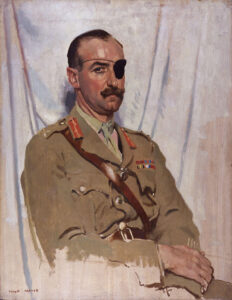

The unkillable soldier…a nickname that has deep ramifications, and a nickname no one really wants to have. It indicates that the soldier is wounded multiple times…and somehow survived. General Adrian Carton de Wiart was that soldier. He was born into an aristocratic family in Brussels, on May 5, 1880. He was the eldest son of Léon Constant Ghislain Carton de Wiart and Ernestine Wenzig. He spent his early days in Belgium and in England. When he was six years old, his parents divorced, and he moved with his father to Cairo. His mother remarried Demosthenes Gregory Cuppa later in 1886. His father was a lawyer and magistrate, as well as a director of the Cairo Electric Railways and Heliopolis Oases Company and was well connected in Egyptian governmental circles. Adrian Carton de Wiart learned to speak Arabic. He joined the British Army at the time of the Second Boer War around 1899, where he entered under the false name of “Trooper Carton,” claiming to be 25 years old, but he was actually 20. He was wounded in the stomach and groin in South Africa early in the Second Boer War and was sent home to recuperate. His father was furious when he learned his son had abandoned his studies. Nevertheless, he allowed his son to remain in the army.

The unkillable soldier…a nickname that has deep ramifications, and a nickname no one really wants to have. It indicates that the soldier is wounded multiple times…and somehow survived. General Adrian Carton de Wiart was that soldier. He was born into an aristocratic family in Brussels, on May 5, 1880. He was the eldest son of Léon Constant Ghislain Carton de Wiart and Ernestine Wenzig. He spent his early days in Belgium and in England. When he was six years old, his parents divorced, and he moved with his father to Cairo. His mother remarried Demosthenes Gregory Cuppa later in 1886. His father was a lawyer and magistrate, as well as a director of the Cairo Electric Railways and Heliopolis Oases Company and was well connected in Egyptian governmental circles. Adrian Carton de Wiart learned to speak Arabic. He joined the British Army at the time of the Second Boer War around 1899, where he entered under the false name of “Trooper Carton,” claiming to be 25 years old, but he was actually 20. He was wounded in the stomach and groin in South Africa early in the Second Boer War and was sent home to recuperate. His father was furious when he learned his son had abandoned his studies. Nevertheless, he allowed his son to remain in the army.

In 1908, he married Countess Friederike Maria Karoline Henriette Rosa Sabina Franziska Fugger von Babenhausen (1887 – 1949), eldest daughter of Karl, 5th Fürst (Prince) von Fugger- Babenhausen and Princess Eleonora zu Hohenlohe-Bartenstein und Jagstberg of Klagenfurt, Austria. They had two daughters, the elder of whom Anita (born 1909, now deceased) was the maternal grandmother of the war correspondent Anthony Loyd (born 1966). I wonder if Loyd was inspired by his grandfather’s story.

Babenhausen and Princess Eleonora zu Hohenlohe-Bartenstein und Jagstberg of Klagenfurt, Austria. They had two daughters, the elder of whom Anita (born 1909, now deceased) was the maternal grandmother of the war correspondent Anthony Loyd (born 1966). I wonder if Loyd was inspired by his grandfather’s story.

Over the course of his career, General Adrian Carton de Wiart earned the nickname “the unkillable soldier.” By 1915, he was promoted to captain and had already survived his first war…the Boer War. One night, near the French battlefield of Ypres, he and a small group of officers wandered too far into enemy territory and ran into a group of German soldiers, who fired. De Wiart was badly shot in the hand but scrambled back to his regiment. According to his memoirs, he used a “scarf he’d taken off a slain German soldier to stop the bleeding.” He was taken to a hospital where surgeons debated what to do about the gory mess of dangling fingers that had been his hand. De Wiart said, “I asked the doctor to take my fingers off; he refused, so I pulled them off myself and felt absolutely no pain in doing it.” De Wairt’s injuries were not over yet. The hand became infected and later had to be amputated. Three weeks later, De Wiart and returned to duty. He was shot several more times in his career, survived two plane crashes, and lost an eye. Over the course of four conflicts,  he sustained 11 grievous injuries, and simply could not be killed in war.

he sustained 11 grievous injuries, and simply could not be killed in war.

En route home via French Indochina, Carton de Wiart stopped in Rangoon as a guest of the army commander. Coming down the stairs, he slipped on coconut matting, fell down, broke several vertebrae, and knocked himself unconscious. He was admitted to Rangoon Hospital where he was treated and recovered. His wife died in 1949. Then, in 1951, at the age of 71, he married Ruth Myrtle Muriel Joan McKechnie, a divorcee known as Joan Sutherland, 23 years his junior (born in late 1903, she died January 13, 2006, at the age of 102.) They settled at Aghinagh House, Killinardrish, County Cork, Ireland. Carton de Wiart died at the age of 83 on June 5, 1963. He left no papers. He and his wife Joan are buried in Caum Churchyard just off the main Macroom road. The grave site is just outside the actual graveyard wall on the grounds of his own home.

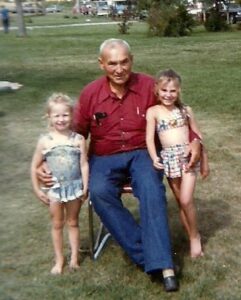

When my husband, Bob’s grandfather, Andy Schulenberg was a boy of 14 years, he was involved in a hunting accident, in which his leg was injured. Things were different in those days, and medicine just wasn’t as advanced as it is now. Not that medicine was antiquated in 1920, but much has been learned about how to save limbs since those days. Grandpa’s leg did not fare well, and after fighting infections, most likely gangrene, and losing the battle, it became apparent that if they were to save his life, they would have to sacrifice the leg.

When my husband, Bob’s grandfather, Andy Schulenberg was a boy of 14 years, he was involved in a hunting accident, in which his leg was injured. Things were different in those days, and medicine just wasn’t as advanced as it is now. Not that medicine was antiquated in 1920, but much has been learned about how to save limbs since those days. Grandpa’s leg did not fare well, and after fighting infections, most likely gangrene, and losing the battle, it became apparent that if they were to save his life, they would have to sacrifice the leg.

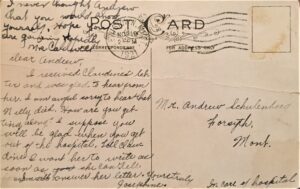

Following the accident and with the amputation, Grandpa send 14 months in the hospital. Now that’s a long time for anyone, but for a 14-year-old boy, that must have felt like an eternity. He missed a year of school, as well as all the fun things kids that age were doing. He also missed helping his parents with various chores, something which might not seem to be a negative thing, but when boredom sets in, a person would far rather work on the farm than lay in a bed. While inventors had dabbled

with the invention of the television, it was by no means perfected, and so he basically had the visitors who came in and books for entertainment. Not much fun really, especially since a lot of boys aren’t terribly interested in reading. Thankfully for Grandpa, his family tried to rally around him, and he received a number of postcard letters during that time. I would imagine he lived for the mail delivery, hoping he got a letter, after which he devoured the words on the page, even if the writer didn’t always pick their words very carefully. It was his connection to the outside world.

with the invention of the television, it was by no means perfected, and so he basically had the visitors who came in and books for entertainment. Not much fun really, especially since a lot of boys aren’t terribly interested in reading. Thankfully for Grandpa, his family tried to rally around him, and he received a number of postcard letters during that time. I would imagine he lived for the mail delivery, hoping he got a letter, after which he devoured the words on the page, even if the writer didn’t always pick their words very carefully. It was his connection to the outside world.

Grandpa was fitted with a wooden peg leg, but it would still be a long road learning to walk with it. I never knew exactly how high the leg went, but I believe it was probably mid-thigh. It was during this time that Grandpa would show his true fortitude He could have laid in that bed, giving up and letting other people take care of him, but he didn’t do that. He got up and worked hard to recover his mobility. Sure, he knew that things would never be the same, but he had things he wanted to do, and he was determined not to let this take him out of commission.

He went on to become the Sheriff of Rosebud County. One might think that he would never want anything to do with guns again, but while he didn’t really see the need for them much as sheriff, he was still well able to use

them. He was sheriff between 1955 and 1972, and during that time, he was well known as “the sheriff without a gun.” It’s hard to imagine a sheriff who has a reputation big enough to be able to work without a gun, including making arrests, but that was what he did. I don’t know if guns bothered him or not, but if so, he was quite successful at hiding it. Today is the 116th anniversary of Grandpa’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandpa Schulenberg!! We love and miss you very much.

them. He was sheriff between 1955 and 1972, and during that time, he was well known as “the sheriff without a gun.” It’s hard to imagine a sheriff who has a reputation big enough to be able to work without a gun, including making arrests, but that was what he did. I don’t know if guns bothered him or not, but if so, he was quite successful at hiding it. Today is the 116th anniversary of Grandpa’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandpa Schulenberg!! We love and miss you very much.

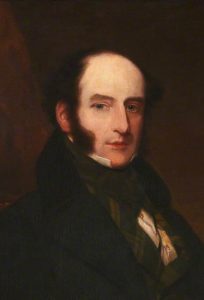

These days, a surgery is performed in comfort, as the patient is under anesthesia, and therefore, feels none of the surgical procedure, at least that is true for most people. There are an unfortunate few for whom anesthesia has little effect. Dr Robert Liston was a pioneering Scottish surgeon, well known for his skills in an era prior to anesthetics, when speed made a difference in terms of pain and survival. For most of us, the idea of a surgery performed in a matter of seconds would not instill much confidence in the doctor…or the procedure, but there was a time when all surgical procedures were performed in this way. People couldn’t take it very long, and the only thing they might have to dull the pain was alcohol…just like we have all seen in the old western movies.

These days, a surgery is performed in comfort, as the patient is under anesthesia, and therefore, feels none of the surgical procedure, at least that is true for most people. There are an unfortunate few for whom anesthesia has little effect. Dr Robert Liston was a pioneering Scottish surgeon, well known for his skills in an era prior to anesthetics, when speed made a difference in terms of pain and survival. For most of us, the idea of a surgery performed in a matter of seconds would not instill much confidence in the doctor…or the procedure, but there was a time when all surgical procedures were performed in this way. People couldn’t take it very long, and the only thing they might have to dull the pain was alcohol…just like we have all seen in the old western movies.

Dr Robert Liston was an expert. He could perform an amputation in seconds. All was going well, and he was a trusted surgeon until 1847, when he was performing an amputation, which he completed in 25 seconds. He was operating so quickly that he accidentally amputated his assistant’s fingers as well. I can only imagine the shock. His was a career filled with skill and excellence, and in an instant, he had a major mistake on his hands.

Dr Liston was famous for his speedy surgeries…often lasting only around 30 seconds. He was well known and respected. In his book “Practical Surgeries,” published in 1837, he emphasizes the importance of quick surgeries, arguing that “these operations must be set about with determination and completed rapidly.” It was all he knew to do. At that time in history, it was the standard of care that everyone expected.

Not everyone believes that the mishap was a true story, and I suppose we will never know, but as the story goes, the case went from bad to worse, when both the patient and the assistant developed sepsis and died. In addition, a spectator reportedly died of shock, meaning that the mortality rate of that one surgery was 300%. While that one surgery was terrible, Dr Liston had many stories of amazing surgeries and miraculous successes. Nevertheless, this one surgery was his most famous. There is a saying by Michael Josephson that goes like this, “We judge ourselves by our best intentions and most noble deeds, but we will be judged by our worst act.” That worst act doesn’t necessarily have to be intentional, and in fact most “worst acts” aren’t intentional. Liston was a good surgeon, and even if he did have this mishap, his overall mortality rate was actually impressive compared to his peers…especially when you consider the speed factor. According to historian Richard Hollingham, “of the 66 patients Liston operated between 1835 and 1840, only 10 died – a death rate of only around 16%.”

When something happens to a child that leaves them missing one limb, it seems like they have a tendency to meet that adversity with a strength and determination that many adults simply don’t. It’s not that the adults couldn’t, but rather that as we get older, sometimes we tend to feel sorry for ourselves instead of making up our mind not to let this become a stumbling block for us.

When something happens to a child that leaves them missing one limb, it seems like they have a tendency to meet that adversity with a strength and determination that many adults simply don’t. It’s not that the adults couldn’t, but rather that as we get older, sometimes we tend to feel sorry for ourselves instead of making up our mind not to let this become a stumbling block for us.

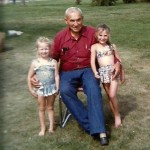

Since I have been conversing with my husband, Bob’s Uncle Butch Schulenberg, my thoughts have often gone back to his dad, Bob’s grandfather, Andrew Schulenberg. I did not know Grandpa Andy until my children were five and six years old, but when I met him, I liked him immediately. He had been the sheriff in Forsyth for many years, and if you had the Schulenberg name, they knew who you belonged to there. The people of Forsyth really liked him. I was very thankful that we had the chance to meet him. It was a visit that I have never forgotten, and have always been thankful to have had.

At first, I wondered if he had lost his leg later in life, because I couldn’t imagine a sheriff with a wooden peg for a leg. Of course, I was wrong, because he lost his leg as a young boy of just fifteen years. He had gone antelope hunting with his friend, Harold Stewart, when his gun accidentally discharged, sending a bullet through his leg. It was a cold October morning in 1921, and medicine not being what it is today, the leg just couldn’t heal. Andy spend 23 months and 11 days in the hospital. Try as they might to save the leg, it simply was not to be. The leg was amputated in June of 1922, eight months after the accident. It was a devastating thing for a teenaged boy, but young Andy determined not to let it stop him.

For Andy, time stood still to a large degree, as it always does when you are in the hospital. I cannot imagine spending almost two years in the hospital, even if a large part of it would be in pain, or so out of it that you barely noticed. I also can’t imagine how it must have been for his parents, who were having to deal with not only the loss of the much needed help of their eldest child, but also with the rest of the family, which was  continuing to grow. Andy missed the birth of his little sister, Bertha, who was born in December 1921, just two months after the accident. That must have been so hard for him and his parents.

continuing to grow. Andy missed the birth of his little sister, Bertha, who was born in December 1921, just two months after the accident. That must have been so hard for him and his parents.

Nevertheless, Andy didn’t let the loss of his leg defeat him. I’m sure it took a long time to figure everything out, but he did, and in the end, became a successful man. When you think about it, people lose limbs in many ways, and it isn’t about the limb in the end, but rather about the constitution of the man or woman that determines the success or failure of the rest of their life. Andy was the kind of man who was made of plenty of determination, and that made all the difference.