Values

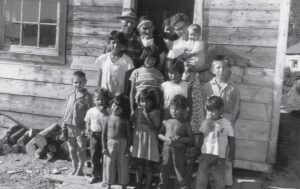

The Sixties Scoop, often referred to simply as The Scoop, was a time when policies in Canada allowed child welfare authorities to remove Indigenous children from their families and communities to place them in foster homes. These children were then adopted by white families. Although it is called the Sixties Scoop, this practice started in the mid-to-late 1950s and continued until the 1980s. There was no given indication that these children were neglected or mistreated, just that they were Indigenous, and supposedly, therefore would be better off in the care of white families. During those years, an estimated 20,000 Indigenous children were removed from their families and placed predominantly with white middle-class families.

The Sixties Scoop, often referred to simply as The Scoop, was a time when policies in Canada allowed child welfare authorities to remove Indigenous children from their families and communities to place them in foster homes. These children were then adopted by white families. Although it is called the Sixties Scoop, this practice started in the mid-to-late 1950s and continued until the 1980s. There was no given indication that these children were neglected or mistreated, just that they were Indigenous, and supposedly, therefore would be better off in the care of white families. During those years, an estimated 20,000 Indigenous children were removed from their families and placed predominantly with white middle-class families.

The program’s policies were not uniform, with each province implementing distinct foster programs and adoption policies. Saskatchewan was unique in having the targeted Indigenous transracial adoption program known as the Adopt Indian Métis (AIM) Program. The term “Sixties Scoop” was first used in the early 1980s by social workers from the British Columbia Department of Social Welfare to describe the practice of child apprehension by their department. This term made its initial appearance in print in a 1983 report by the Canadian Council on Social Development, entitled “Native Children and the Child Welfare System.” Researcher Patrick Johnston cited the term’s origin and utilized it in his report. This term is akin to “Baby Scoop Era,” denoting the time from the late 1950s to the 1980s when many children were removed from unmarried mothers for adoption. These mothers were given no choice in the matter.

The government policies responsible for the Sixties Scoop were abandoned in the mid-1980s following resolutions passed by Ontario chiefs and severe condemnation from a Manitoba judicial inquiry. The inquiry, led by Associate Chief Judge Edwin C. Kimelman, culminated in the release of “No Quiet Place / Review Committee on Indian and Métis Adoptions and Placements,” commonly referred to as the “Kimelman Report.” Numerous lawsuits have been initiated in Canada by individuals who were part of the Sixties Scoop, including class-action suits in five provinces, such as the one initiated in British Columbia in 2011. Chief Marcia Brown Martel of the Beaverhouse First Nation was the lead plaintiff in the Ontario class-action suit filed in 2009. On February 14, 2017, Justice Edward Belobaba of the Ontario Superior Court found the government responsible for damages caused by the Sixties Scoop. Subsequently, on October 6, 2017, an $800-million settlement was disclosed for the Martel case. Currently, Métis and non-status First Nations individuals are not included in the settlement, prompting the National Indigenous Survivors of Child Welfare Network…an organization led by survivors of the Sixties Scoop in Ottawa…to call for the rejection of the settlement unless it encompasses all Indigenous individuals who were removed from their homes and placed into forced adoption.

The Sixties Scoop began during a period when Indigenous families were already grappling with the consequences of the Canadian Indian residential school system. This network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples adversely affected their social, economic, and living conditions. The residential school system remained operational until the closure of the last school in 1996. Established by the federal government and managed by various churches, the system’s goal was to assimilate Aboriginal children by teaching them Euro-Canadian and Christian values. It enforced policies that prohibited the children from speaking their native languages, communicating with their families, or practicing their cultural traditions. Survivors of residential schools have spoken out about the physical, spiritual, sexual, and psychological abuse they endured from the staff. The enduring cultural impact on First Nations, Métis, and Inuit families and communities is both widespread and profound.

The Sixties Scoop involved the forced removal of children from their Indigenous lands and communities, often without the consent or knowledge of their families or tribes. Siblings were frequently separated and sent to different areas to prevent any communication with their relatives. These children were denied knowledge of their true nationality, history, or family ties. If a child sought to learn about their cultural identity, they required consent from their biological parents. However, due to the government’s efforts to sever ties between the children and their biological families, access to their birth records was impossible. Consequently, while the children might have suspected their cultural heritage, they had no means to verify it with concrete evidence.

The Canadian government began the process of closing the mandatory residential school system in the 1950s and 1960s, believing that Aboriginal children would receive a superior education within the public school system. A summary states: “This transition to provincial services led to a 1951 [Indian Act] amendment that enabled the province to provide services to Aboriginal people where none existed federally. Child protection was one of these areas. In 1951, twenty-nine Aboriginal children were in provincial care in British Columbia; by 1964, that number was 1,466. Aboriginal children, who had comprised only 1 percent of all children in care, came to make up just over 34 percent.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada, established as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, was tasked with recording the experiences of Indigenous children in residential schools. Its mission was to disseminate the truths of survivors, their families, communities, and all those impacted, to the Canadian populace. The TRC’s final report, released in 2015, details these findings: “By the end of the 1970s, the transfer of children from residential schools was nearly complete in Southern Canada, and the impact of the Sixties Scoop was in evidence across the country.” First Nations have persistently resisted such policies through various means, including legal challenges (Natural Parents v. Superintendent of Child Welfare, 1976, 60 D.L.R. 3rd 148 S.C.C) and the establishment of their own policies, like the Spallumcheen Indian Band’s by-law to manage its child welfare program, achieving varying levels of success.

In response to the loss of their children and the subsequent cultural genocide, First Nations communities took

action by repatriating children from failed adoptions and striving to reclaim authority over their children’s welfare practices. This movement began in 1973 with the Blackfoot (Siksika) child welfare agreement in Alberta. Currently, there are approximately 125 First Nations Child and Family Service Agencies in Canada, operating under a variety of agreements that grant them authority from provincial governments to offer services, with funding provided by the federal government.

action by repatriating children from failed adoptions and striving to reclaim authority over their children’s welfare practices. This movement began in 1973 with the Blackfoot (Siksika) child welfare agreement in Alberta. Currently, there are approximately 125 First Nations Child and Family Service Agencies in Canada, operating under a variety of agreements that grant them authority from provincial governments to offer services, with funding provided by the federal government.

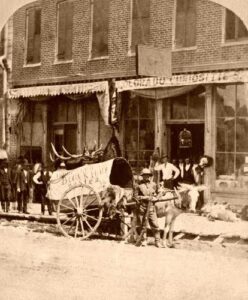

As mining work started up in the United States, the need for housing in the area of the mines started up too. This need brought about the “company town” as a place where all or most of the stores and housing in the town are owned by the same company. Of course, this meant that quite often, all or most of the wages paid to workers, came back to the company in purchases, and as we all know stores and such always have a markup so that they make a profit. Still, they did meet a need, and there was often nowhere else to go. Company towns were often planned with a number of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schools, markets, and recreation facilities.

As mining work started up in the United States, the need for housing in the area of the mines started up too. This need brought about the “company town” as a place where all or most of the stores and housing in the town are owned by the same company. Of course, this meant that quite often, all or most of the wages paid to workers, came back to the company in purchases, and as we all know stores and such always have a markup so that they make a profit. Still, they did meet a need, and there was often nowhere else to go. Company towns were often planned with a number of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schools, markets, and recreation facilities.

The initial motive of building the “company towns” was to improve living conditions for workers. Nevertheless, many have been regarded as controlling and often exploitative. Others were not planned, such as Summit Hill, Pennsylvania, United States, one of the oldest, which began as a Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company mining camp and mine site nine miles from the nearest outside road. Just being that far from anything else around, was prohibitive to those who felt like they were the victims of gouging. Today, many of those “company towns” are ghost towns…lost to a bygone era.

One such town, the town of Kempton, West Virginia was located just a few feet inside the West Virginia border. This strategic location allowed the company to operate using scrip rather than cash. To me that seems like a move to a cashless system that further held the workers there, because the scrip was only accepted at the company businesses, thereby eliminating outside competition. As with any monopoly, this created price  gouging. To make matters worse, if an employee needed a “big ticket” item, such as such as washing machines, radios, and refrigerators, they could get them and make payments. This put many miners in debt, and they were required to pay off the debt before they could move away. The town of Kempton was “founded in 1913 by the Davis Coal and Coke Company, a strip of land 3/4 of a mile long and several hundred feet wide was cleared for the construction of company houses, four to six rooms each with a front yard and a garden in the back. In 1915, J Weimer became the first schoolteacher at $40 a month with 53 pupils. The company store was located on the West Virginia side along with the Opera House that contained the lunchroom, bowling alley, pool table, dancing floor, auditorium, and the post office.” These towns were in reality, “privatized” towns run by a government that was neither elected nor fair, they were simply the ones in control, and if people wanted a job they dealt with the rules.

gouging. To make matters worse, if an employee needed a “big ticket” item, such as such as washing machines, radios, and refrigerators, they could get them and make payments. This put many miners in debt, and they were required to pay off the debt before they could move away. The town of Kempton was “founded in 1913 by the Davis Coal and Coke Company, a strip of land 3/4 of a mile long and several hundred feet wide was cleared for the construction of company houses, four to six rooms each with a front yard and a garden in the back. In 1915, J Weimer became the first schoolteacher at $40 a month with 53 pupils. The company store was located on the West Virginia side along with the Opera House that contained the lunchroom, bowling alley, pool table, dancing floor, auditorium, and the post office.” These towns were in reality, “privatized” towns run by a government that was neither elected nor fair, they were simply the ones in control, and if people wanted a job they dealt with the rules.

Cut out of the Appalachian wilderness, the town of Kempton flourished and became a vibrant community rich in culture and familial spirit. Then, when the mine closed in April of 1950, it just as quickly faded into oblivion. Nevertheless, the former residents tried to keep their connections alive. They held a reunion in 1952 to share their memories and to recall a strong sense of home. Unfortunately, what were once good intention, faded as life got busy and people moved around. Finally, the forest began to reclaim many of the houses as weeds took over and neglect allowed for decay. These days, the fruit trees and annual flowers that were planted long ago

by people who loved the place “still bloom to greet the Spring” and a few of the broken-down buildings still dot the landscape, if one in incline to look around. Newer homes have been built, that are privately owned, and mixed in are a few of the old remnants of times past. With mine reclamation laws in place now, groups have come in and performed archeological digs to recover old work items from the past and restore the site to historical status.

by people who loved the place “still bloom to greet the Spring” and a few of the broken-down buildings still dot the landscape, if one in incline to look around. Newer homes have been built, that are privately owned, and mixed in are a few of the old remnants of times past. With mine reclamation laws in place now, groups have come in and performed archeological digs to recover old work items from the past and restore the site to historical status.

The Circus Maximus, which is Latin for largest circus is an ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. It is located in the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, and it was the first and largest stadium in ancient Rome and its later Empire. It measured 2,037 feet in length and 387 feet in width and could accommodate over 150,000 spectators. In its fully developed form, it became the model for circuses throughout the Roman Empire. The site is now a public park. In its beginning, it might have been planned for good, clean-cut entertainment, but in at least part of its history, it was used for much more sinister things. It was during the Roman Empire, when the empire decided that anyone who was not a Roman citizen was basically unimportant.

The Circus Maximus, which is Latin for largest circus is an ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. It is located in the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, and it was the first and largest stadium in ancient Rome and its later Empire. It measured 2,037 feet in length and 387 feet in width and could accommodate over 150,000 spectators. In its fully developed form, it became the model for circuses throughout the Roman Empire. The site is now a public park. In its beginning, it might have been planned for good, clean-cut entertainment, but in at least part of its history, it was used for much more sinister things. It was during the Roman Empire, when the empire decided that anyone who was not a Roman citizen was basically unimportant.

As it has been throughout history, the Roman Empire was notorious for its persecution of Christian and Jewish people. During those years, the Circus Maximus was used for the execution of Christian and Jewish prisoners, as part of the Roman Triumph, along with chariot racing, of course. As we all know, the Roman Empire worshiped a number of gods, which put them in direct conflict with the one true God, and thereby, put them at odds with the Christians and Jews. During those years, Christians were persecuted and prosecuted, throughout the Roman Empire.

Pagan practices such as making sacrifices to the deified emperors or other gods were abhorrent to Christians as their beliefs prohibited idolatry. When they would not comply with the pagan practices, they were prosecuted by the state and other members of civic society and severely punished for “treason, various rumored crimes, illegal assembly, and for introducing an alien cult that led to Roman apostasy.” The first, localized Neronian persecution occurred under Emperor Nero (BC54-BC68) in Rome. A more general persecution occurred during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (BC161-BC180). After a lull, persecution resumed under Emperors Decius (BC249–BC251) and Trebonianus Gallus (BC251–BC253). The Decian persecution was particularly extensive. The persecution of Emperor Valerian (BC253–BC260) ceased with his notable capture by the Sasanian Empire’s Shapur I (BC240–BC270) at the Battle of Edessa during the Roman–Persian Wars. His successor, Gallienus

(BC253–BC268), halted the persecutions. Most, if not all of these emperors were viciously wicked men, including Gallienus, who finally stopped this horrific practice. Nevertheless, he did stop it, so that is a good thing. There is a right and wrong way to put someone on trial, and most importantly, there should always be freedom of religion, but not all countries allow freedom of religion.

(BC253–BC268), halted the persecutions. Most, if not all of these emperors were viciously wicked men, including Gallienus, who finally stopped this horrific practice. Nevertheless, he did stop it, so that is a good thing. There is a right and wrong way to put someone on trial, and most importantly, there should always be freedom of religion, but not all countries allow freedom of religion.

Recently, my sisters, Cheryl Masterson, Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, Allyn Hadlock, and I started a book club. Before each meeting, we read a book, on our own time, and then come together to discuss the book we read. We chose the Presidents of the United States as our topics, and each time we progress to the next president. We began at the beginning, President George Washington. We went on to John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and next will be James Monroe. One takeaway from these books has been that while our founding fathers may have had their faults, and some more than others, each tried to do what they saw as the best thing for this nation. They also knew that more than anything, we needed freedom. We could not continue to live under British rule.

Recently, my sisters, Cheryl Masterson, Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, Allyn Hadlock, and I started a book club. Before each meeting, we read a book, on our own time, and then come together to discuss the book we read. We chose the Presidents of the United States as our topics, and each time we progress to the next president. We began at the beginning, President George Washington. We went on to John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and next will be James Monroe. One takeaway from these books has been that while our founding fathers may have had their faults, and some more than others, each tried to do what they saw as the best thing for this nation. They also knew that more than anything, we needed freedom. We could not continue to live under British rule.

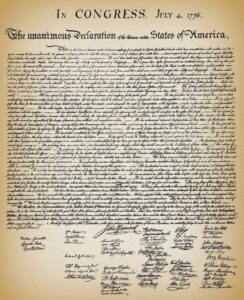

We had to be free of England, and so it was that Independence Day, also known as the Fourth of July, is now a federal holiday in the United States commemorating that freedom, and the Declaration of Independence, which  was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing the United States of America. The Declaration of Independence was largely written by Thomas Jefferson but was collectively the work of the Committee of Five, which also included John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. The Founding Father delegates of the Second Continental Congress declared that “the Thirteen Colonies were no longer subject (and subordinate) to the monarch of Britain, King George III, and were now united, free, and independent states.” The Congress voted to approve independence by passing the Lee Resolution on July 2 and adopted the Declaration of Independence two days later, on July 4. We were a free nation, but that did not mean that Great Britain would willingly accept that. In fact, Great Britain did not accept US independence until 1783…a full seven years after it was first declared.

was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing the United States of America. The Declaration of Independence was largely written by Thomas Jefferson but was collectively the work of the Committee of Five, which also included John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. The Founding Father delegates of the Second Continental Congress declared that “the Thirteen Colonies were no longer subject (and subordinate) to the monarch of Britain, King George III, and were now united, free, and independent states.” The Congress voted to approve independence by passing the Lee Resolution on July 2 and adopted the Declaration of Independence two days later, on July 4. We were a free nation, but that did not mean that Great Britain would willingly accept that. In fact, Great Britain did not accept US independence until 1783…a full seven years after it was first declared.

Like many “start-up” countries, the United States met with heavy opposition the minute it tried to get going. The “Mother Country” didn’t want to let go. Great Britain called the United States the “Colonies” long after we

were actually a free nation. Even when they knew they had lost any control over the United States, they tried to get it back, and in the absence of getting their control back, they downplayed the importance of the United States. That was probably the most ridiculous part of it, because the United States became the most powerful nation in the world. While some might disagree, and while we have had our ups and downs, this nation will always stand. Today, we celebrate the nation that we love. The United States of America…the home of the free, because of the brave. Happy Independence Day to this great nation!! Let the celebration begin!!

were actually a free nation. Even when they knew they had lost any control over the United States, they tried to get it back, and in the absence of getting their control back, they downplayed the importance of the United States. That was probably the most ridiculous part of it, because the United States became the most powerful nation in the world. While some might disagree, and while we have had our ups and downs, this nation will always stand. Today, we celebrate the nation that we love. The United States of America…the home of the free, because of the brave. Happy Independence Day to this great nation!! Let the celebration begin!!

My aunt, Virginia Beadle was the second daughter of my grandparents, Hattie and George Byer. Like her older sister, Evelyn Hushman, Aunt Virginia helped with their younger siblings. When you come from a family of nine children, there are always babies to care for. I don’t suppose the girls always loved taking care of their siblings. Younger siblings can be a trial to the older kids…especially as the older kids head into their teen years. Nevertheless, they did what was needed. Still, when Aunt Virginia found out that since her sister was the main babysitter, and she didn’t have to do housework after a late night of babysitting, Aunt Virginia, who hated housework, asked if the same rule would apply to her if she was working. When Grandma said it would, the deal was sealed. Aunt Virginia went out and got herself a job. She always had one after that, and true to her word, Grandma didn’t make her do housework. I don’t know how long that deal lasted, but for a teenager, who hated housework, it was a good deal.

My aunt, Virginia Beadle was the second daughter of my grandparents, Hattie and George Byer. Like her older sister, Evelyn Hushman, Aunt Virginia helped with their younger siblings. When you come from a family of nine children, there are always babies to care for. I don’t suppose the girls always loved taking care of their siblings. Younger siblings can be a trial to the older kids…especially as the older kids head into their teen years. Nevertheless, they did what was needed. Still, when Aunt Virginia found out that since her sister was the main babysitter, and she didn’t have to do housework after a late night of babysitting, Aunt Virginia, who hated housework, asked if the same rule would apply to her if she was working. When Grandma said it would, the deal was sealed. Aunt Virginia went out and got herself a job. She always had one after that, and true to her word, Grandma didn’t make her do housework. I don’t know how long that deal lasted, but for a teenager, who hated housework, it was a good deal.

One of the coolest events of Aunt Virginia’s life was the day happened when she was about 8 or 10 years old.

She was playing outside with her siblings. Aunt Virginia decided to go exploring at the side of the house, between their house and Great Grandma Byer’s house. She looked at the little flower garden there and saw something shiny. When she picked it up, she saw that his was a man’s wedding ring. Great Grandpa was long dead, and her dad, Grandpa George Byer, had decided to forego a wedding ring so that he could give his bride, her mom and my grandma, Hattie Byer a wedding ring. Obviously, this was an exciting, and quite likely valuable, find.

She was playing outside with her siblings. Aunt Virginia decided to go exploring at the side of the house, between their house and Great Grandma Byer’s house. She looked at the little flower garden there and saw something shiny. When she picked it up, she saw that his was a man’s wedding ring. Great Grandpa was long dead, and her dad, Grandpa George Byer, had decided to forego a wedding ring so that he could give his bride, her mom and my grandma, Hattie Byer a wedding ring. Obviously, this was an exciting, and quite likely valuable, find.

Aunt Virginia took the ring to show her dad. Grandpa looked at it and told her it was a beautiful ring. He put it on his hand and looked at it. Then he took it off and gave it back to Aunt Virginia. She said, “Daddy, you should keep it.” He said he couldn’t, but she insisted, and that is how my grandfather got his wedding band from his daughter. Aunt Virginia was so pleased to be able to give her dad the wedding ring he had never had and would

not be able to buy for himself, as there were too many other things that his paycheck was needed for. And Grandpa was so pleased that she wanted him to have such a beautiful ring. He wore the ring proudly for the rest of his life. And everyone in his family was very pleased that he had been blessed with the ring. Aunt Virginia was always a kind and loving person, and I can see how that ring made her day, as much as it did Grandpa’s. Today would have been Aunt Virginia’s 94th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Aunt Virginia. We love and miss you very much!!

not be able to buy for himself, as there were too many other things that his paycheck was needed for. And Grandpa was so pleased that she wanted him to have such a beautiful ring. He wore the ring proudly for the rest of his life. And everyone in his family was very pleased that he had been blessed with the ring. Aunt Virginia was always a kind and loving person, and I can see how that ring made her day, as much as it did Grandpa’s. Today would have been Aunt Virginia’s 94th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Aunt Virginia. We love and miss you very much!!

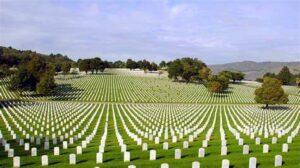

Memorial Day is a different kind of day, because it is not a holiday of celebration, but rather a day remembrance. We cannot celebrate this day, because it is about honoring those soldiers who went to war and didn’t make it back. It was the ultimate sacrifice. As the saying goes concerning soldiers, “all gave some, but some gave all!” When a soldier goes to war, they know. They are very aware that the possibility exists that they will not come back home. They know that their sacrifice might be the ultimate sacrifice. They want to make it home, but they know it may not be. Today is about those soldiers who did not make it home.

Memorial Day is a different kind of day, because it is not a holiday of celebration, but rather a day remembrance. We cannot celebrate this day, because it is about honoring those soldiers who went to war and didn’t make it back. It was the ultimate sacrifice. As the saying goes concerning soldiers, “all gave some, but some gave all!” When a soldier goes to war, they know. They are very aware that the possibility exists that they will not come back home. They know that their sacrifice might be the ultimate sacrifice. They want to make it home, but they know it may not be. Today is about those soldiers who did not make it home.

I doubt if there are many families that can say that they have never lost a soldier in battle, but while I don’t specifically know of any in my family, I’m sure there are some back there a way. There have been many wars, and with each one examined, comes the increased chance of having a relative who dies at war. It doesn’t matter anyway, because Memorial Day is a day to honor those who gave all, whether they are related to us or not. Their sacrifice is what makes us free today. They fought for people they didn’t even know, gave up time with the family they loved, and died in a place they didn’t want to be. That is the epitome of bravery and courage.

Some of them, including my uncle, Jim Richards’ brother Dale Richards never left the place they died. Dale fought in Normandy, France, and that is where he is to this day. The people of France are so grateful for the soldiers who fought and died over there, that they keep the graves looking beautiful. It’s nice to know that there are people who continue to show their appreciation for those men who “gave all” for them. Their sacrifice should never be forgotten. Their families can certainly never forget. They have had to go forward with their lives without the love and support of the soldier that went to war and never came home. That soldier had

potential. They could have been anything they wanted to be, but instead, they chose to give their life to ensure the freedom of other human beings. Today, we honor all of those men who “gave all” for us and so many others. We thank you for your service, and we honor your memory. God bless you all, from a grateful nation.

potential. They could have been anything they wanted to be, but instead, they chose to give their life to ensure the freedom of other human beings. Today, we honor all of those men who “gave all” for us and so many others. We thank you for your service, and we honor your memory. God bless you all, from a grateful nation.

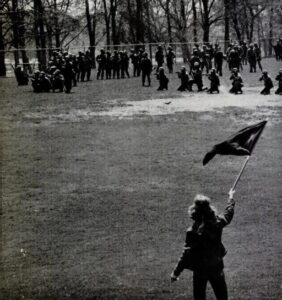

The Vietnam War was a volatile time in American history. When the war started, so did the draft. Many people protested, especially students. I suppose for them, it all felt so much closer to home, than for the older Americans. Still, the students were not alone in protesting. Many Americans agreed and protested too. The law allows for “peaceful” protesting, saying that it is “a constitutionally protected form of expression under the First Amendment in the United States. It falls under the right to free assembly, allowing every American to voice their opinions and advocate for change. However, a protest becomes a riot when one or more people within the group engage in criminal activity. This can include intentionally damaging property or causing physical harm to another person1. In other words, when a peaceful demonstration loses control and turns violent, it transitions from a protest to a riot.”

The Vietnam War was a volatile time in American history. When the war started, so did the draft. Many people protested, especially students. I suppose for them, it all felt so much closer to home, than for the older Americans. Still, the students were not alone in protesting. Many Americans agreed and protested too. The law allows for “peaceful” protesting, saying that it is “a constitutionally protected form of expression under the First Amendment in the United States. It falls under the right to free assembly, allowing every American to voice their opinions and advocate for change. However, a protest becomes a riot when one or more people within the group engage in criminal activity. This can include intentionally damaging property or causing physical harm to another person1. In other words, when a peaceful demonstration loses control and turns violent, it transitions from a protest to a riot.”

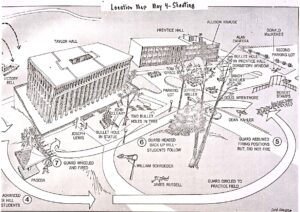

On May 2, 1970, a protest rally at Kent State University resulted in the National Guard troops being called out to suppress students who were now rioting in protest of the Vietnam War and the US invasion of Cambodia. As scattered protests continued the next day, they were dispersed by tear gas, and on May 4th class resumed at Kent State University. University officials put a ban of rallies, but it didn’t stop the rallies. By noon, some 2,000 people had assembled on the campus. The National Guard troops arrived and ordered the crowd to disperse, fired tear gas, and advanced against the students with bayonets fixed on their rifles. As is common among protesters, some refused to disperse, and even responded by throwing rocks and verbally taunting the troops.

As the situation escalated, and without firing a warning shot, 28 Guardsmen discharged more than 60 rounds  toward a group of demonstrators in a nearby parking lot, killing four and wounding nine, one of whom would be permanently paralyzed. The closest casualty was 20 yards away, and the farthest was almost 250 yards away. After a period of disbelief, shock, and attempts at first aid, angry students gathered on a nearby slope and were again ordered to move by the Guardsmen. Though they were prepared to stand and even die for their beliefs, faculty members were able to convince the group to disperse, and further bloodshed was prevented. The Kent State campus was closed for six weeks following the tragedy.

toward a group of demonstrators in a nearby parking lot, killing four and wounding nine, one of whom would be permanently paralyzed. The closest casualty was 20 yards away, and the farthest was almost 250 yards away. After a period of disbelief, shock, and attempts at first aid, angry students gathered on a nearby slope and were again ordered to move by the Guardsmen. Though they were prepared to stand and even die for their beliefs, faculty members were able to convince the group to disperse, and further bloodshed was prevented. The Kent State campus was closed for six weeks following the tragedy.

News of the shootings reverberated across the globe. It also led to protests on college campuses across the country. Just five days after the shootings, 100,000 people demonstrated in Washington, DC, both against the war and the killing of unarmed student protesters. The media put out photographs of the massacre, and the images became enduring images of the anti-war movement. A criminal investigation followed, and in 1974, at the end of the investigation, a federal court dropped all charges levied against eight Ohio National Guardsmen for their role in the Kent State students’ deaths. The decision was followed by outrage.

After the decision was made, the defendants issued a statement, “In retrospect, the tragedy of May 4, 1970, should not have occurred. The students may have believed that they were right in continuing their mass protest in response to the Cambodian invasion, even though this protest followed the posting and reading by the university of an order to ban rallies and an order to disperse. These orders have since been determined by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals to have been lawful.

Some of the Guardsmen on Blanket Hill, fearful and anxious from prior events, may have believed in their own  minds that their lives were in danger. Hindsight suggests that another method would have resolved the confrontation. Better ways must be found to deal with such a confrontation.

minds that their lives were in danger. Hindsight suggests that another method would have resolved the confrontation. Better ways must be found to deal with such a confrontation.

We devoutly wish that a means had been found to avoid the May 4th events culminating in the Guard shootings and the irreversible deaths and injuries. We deeply regret those events and are profoundly saddened by the deaths of four students and the wounding of nine others which resulted. We hope that the agreement to end the litigation will help to assuage the tragic memories regarding that sad day.” I agree, better ways must be found by both the protesters and the authorities.

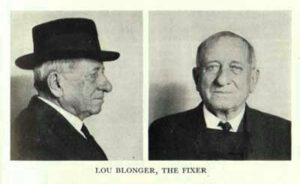

Louis H Blonger was born in Swanton, Vermont, on May 13, 1849. He was the eighth of 13 children. His father, Simon Peter Belonger, was a stonemason born in Canada of French ancestry. His mother, Judith Kennedy, was raised in an orphanage in Nenagh, County Tipperary, Ireland. The Belonger family migrated from Vermont to the lead mining village of Shullsburg, Wisconsin, when Lou was five years old. Sadly, his mother died in 1859, and Lou was sent to live with his older sister and her husband for a few years. It was around that time, that Blonger began using a shortened version of the family name (omitting the first “e”), as most of his brothers did.

Louis H Blonger was born in Swanton, Vermont, on May 13, 1849. He was the eighth of 13 children. His father, Simon Peter Belonger, was a stonemason born in Canada of French ancestry. His mother, Judith Kennedy, was raised in an orphanage in Nenagh, County Tipperary, Ireland. The Belonger family migrated from Vermont to the lead mining village of Shullsburg, Wisconsin, when Lou was five years old. Sadly, his mother died in 1859, and Lou was sent to live with his older sister and her husband for a few years. It was around that time, that Blonger began using a shortened version of the family name (omitting the first “e”), as most of his brothers did.

The Civil War broke out when Lou was just 15 years old. While he was technically just a boy, Lou enlisted in the Union Army anyway. While he was a soldier, someone must have known that he was quite young, and he soon found himself playing a musical instrument called a fife, helping to keep the marching pace of the soldiers. A Fifer was a common job for those boys who were too young to fight. When the war ended, Lou joined up with his older brother, Sam. The boys headed west hoping to make their fortunes in the many Colorado, Utah, and Nevada mining camps. As they were about to find out, mining isn’t the easiest way to make “your fortune” and so they found themselves moving from camp to camp, taking various jobs working in saloons and mines while doing a little prospecting, plenty of gambling, and practicing several con games in cities across the West, from Deadwood, South Dakota, to Silver City, New Mexico, and on to San Francisco, California. For a short time, Lou and Sam even served as lawmen in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where they were said to have provided protection for Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp.

The brothers could be found in Denver, Colorado by the 1880s, where they ran a saloon on Larimer Street and later on Stout Street. Within ten years, they had become wealthy from their investments in mining claims, as well as their profits from their popular Denver saloons. Their saloons catered to gamblers and provided “painted ladies” for their customers, but it was far more due to their various games of fraud and graft practiced on many  a hapless miner, that brought in the most money for the pair. While in Denver, they practiced their cons widely, in open competition with the well-known Soapy Smith Gang. Eventually, the Blonger brothers took over control as the “Kingpins” of the Denver underworld, when Soapy Smith moved on in 1896. They consolidated the city’s competing gangs of confidence men into a single organization.

a hapless miner, that brought in the most money for the pair. While in Denver, they practiced their cons widely, in open competition with the well-known Soapy Smith Gang. Eventually, the Blonger brothers took over control as the “Kingpins” of the Denver underworld, when Soapy Smith moved on in 1896. They consolidated the city’s competing gangs of confidence men into a single organization.

Operating their “business” as a “big store” con, or fake betting house, central facilities were established, complete with betting windows, chalkboards for race results, and ticker-tape machines. Here, the gang members would convince unsuspecting customers to put up large sums of cash to secure the delivery of promised stock profits or winning bets on horse races. It was this practice that is portrayed in the movie, The Sting. Lou also had several men working for him who profited as pickpockets, shell-game experts, and other small-time con games. Lou’s operation was so tight that no one could operate in the city without gaining his permission and “donating” a share of their proceeds to him. Not satisfied with their original influence, they began to wield their power by influencing elections and political appointments to protect their racket and shield their gang members from prosecution.

Blonger added a second-in-command, named Adolph W “Kid” Duff in 1904. Duff was an experienced hand, having long been a member of several other Colorado gangs and well known as a gambler, opium dealer, and pickpocket. With this addition, the profits of the “organization” increased, and by 1920, Lou Blonger had grown so powerful that many said he “owned” the city of Denver. He was said to be able to fix any arrest with a phone call and was making thousands of illegal dollars a year in his extensive confidence games. Lou even had a private telephone line in his office that ran directly to the chief of police…who was also corrupt. Lou had become known as “The Fixer” and had become one of the leaders of the longest-running confidence rings in the American West. Nevertheless, even this was a doomed enterprise.

Blonger had been a decent young man turned successful criminal for decades, when in 1922, it all ended. Di

strict Attorney Philip S Van Cise circumvented the corrupt Denver politicians and established his own “secret force” of local citizens. They were funded by private donations, an Van Cise’s men were able to arrest 33 confidence men, including Louis Blonger and “Kid” Duff. The trial was big news and highly publicized. The people were tired of the corruption, and upon their conviction, Louis Blonger and many other gang members were sentenced to prison in Cañon City, Colorado. Lou Blonger and “Kid”, Duff received sentences of seven to ten years, nevertheless, Blonger would again escape hi “due punishment” when just five months after going to prison, he died on April 20, 1924, at the age of 74. Duff, in the meantime, was out on bond pending another court case, when he committed suicide. You might be wondering what Lou’s older brother Sam was doing at this time. Sam had died some ten years earlier.

strict Attorney Philip S Van Cise circumvented the corrupt Denver politicians and established his own “secret force” of local citizens. They were funded by private donations, an Van Cise’s men were able to arrest 33 confidence men, including Louis Blonger and “Kid” Duff. The trial was big news and highly publicized. The people were tired of the corruption, and upon their conviction, Louis Blonger and many other gang members were sentenced to prison in Cañon City, Colorado. Lou Blonger and “Kid”, Duff received sentences of seven to ten years, nevertheless, Blonger would again escape hi “due punishment” when just five months after going to prison, he died on April 20, 1924, at the age of 74. Duff, in the meantime, was out on bond pending another court case, when he committed suicide. You might be wondering what Lou’s older brother Sam was doing at this time. Sam had died some ten years earlier.

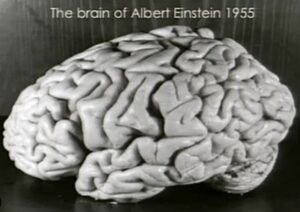

Many advancements have been made in our world through the studies of science. Still, sometimes, scientists take their study of science just a little bit too far, in the name of science. There isn’t a person in the world who hasn’t heard of Albert Einstein. He was not only the iconic, but common to geniuses, Einstein was also eccentric. Nevertheless, he was a brilliant scientist, mathematician, and one of the most intelligent people in history. Because of his brilliance, Einstein also knew that upon his death, there would undoubtedly be some crazy scientist who would want to study his brain. I can’t imagine knowing that my brain would be in demand, and in fact might be stolen after I had died. That seems totally insane to me, but for Einstein, it was a very real possibility. Knowing that, Einstein left detailed instructions to cremate his body and not to allow any brain examinations.

Many advancements have been made in our world through the studies of science. Still, sometimes, scientists take their study of science just a little bit too far, in the name of science. There isn’t a person in the world who hasn’t heard of Albert Einstein. He was not only the iconic, but common to geniuses, Einstein was also eccentric. Nevertheless, he was a brilliant scientist, mathematician, and one of the most intelligent people in history. Because of his brilliance, Einstein also knew that upon his death, there would undoubtedly be some crazy scientist who would want to study his brain. I can’t imagine knowing that my brain would be in demand, and in fact might be stolen after I had died. That seems totally insane to me, but for Einstein, it was a very real possibility. Knowing that, Einstein left detailed instructions to cremate his body and not to allow any brain examinations.

As sometimes happens, even when a detailed and legal will is written, there are those who do not necessarily think that it needs to be followed. I think that is just heinous!! When Einstein died in 1955, a scientist named Thomas Stoltz Harvey conducted the autopsy. This man completely disregarded the will that was written by Albert Einstein, and despite the family not granting permission, he stole Einstein’s brain and took it to the University of Philadelphia to study it. When they found out about the theft, Einstein’s family decided to give  permission to Harvey to go ahead and study Einstein’s brain, as long as he published the finding in a scientific magazine. At that point they had few other options. Still, I believe it was a criminal act, and Harvey should have been punished to the fullest extent of the law.

permission to Harvey to go ahead and study Einstein’s brain, as long as he published the finding in a scientific magazine. At that point they had few other options. Still, I believe it was a criminal act, and Harvey should have been punished to the fullest extent of the law.

After, Harvey stole Einstein’s brain, “it was preserved, photographed, dissected, and even mailed to other scientists in hopes that studying it might uncover the source of his genius. Over decades, several interesting features of his brain have been discovered, including more extensive connections between the two hemispheres of his brain, a lighter than average weight, and an enlarged lateral sulcus. The part of his brain dedicated to mathematical and spatial thought, the inferior parietal lobe, was larger than average as well.” These days, you can view his brain (now with permission from his family)…or what is left of it after the mutilation it was subjected to, in the permanent exhibitions of the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I don’t think “in the name of science” should be a license to steal something that belongs to someone else. Their body parts, whether needed for a transplant or for scientific study, should not be allowed. If a person wanted their body donated for science or transplant, they would have stated as much. I understand a family allowing a transplant if no specific instructions were given, but when specific instructions were given, as in the case of Albert Einstein, how dare someone decide that their desires are more important than the desires of the

deceased!! Once the damage was done, and the brain was stolen, Einstein’s family made the decision not to prosecute, but rather to allow the scientific testing. It was a gracious move on their part, and an act of mercy that was most certainly not earned by one Thomas Stoltz Harvey!! I also speculate that it could have opened the door for additional victims…allowed in the name of science. This was just wrong…in so many ways!!

deceased!! Once the damage was done, and the brain was stolen, Einstein’s family made the decision not to prosecute, but rather to allow the scientific testing. It was a gracious move on their part, and an act of mercy that was most certainly not earned by one Thomas Stoltz Harvey!! I also speculate that it could have opened the door for additional victims…allowed in the name of science. This was just wrong…in so many ways!!

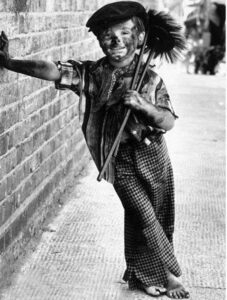

Perhaps one of the most questionable of all professions undertaken by children in the past was that of chimney sweeping. Not only were children exploited in this job, mostly because of their small stature, but since proper safety measures were not taken in those days, the children in those jobs had health problems for the rest of their lives, and very likely they died young. The use of children as chimney sweeps began in the late 1600s in England, after the Great Fire of London, which gutted the city. At that time, building codes changed, requiring chimneys to be much narrower than they were previously. The idea was to keep more of the sparks in than out.

Perhaps one of the most questionable of all professions undertaken by children in the past was that of chimney sweeping. Not only were children exploited in this job, mostly because of their small stature, but since proper safety measures were not taken in those days, the children in those jobs had health problems for the rest of their lives, and very likely they died young. The use of children as chimney sweeps began in the late 1600s in England, after the Great Fire of London, which gutted the city. At that time, building codes changed, requiring chimneys to be much narrower than they were previously. The idea was to keep more of the sparks in than out.

The new design brought with it a bigger problem…keeping the chimneys free of obstruction, which became more of a challenge and a priority. Amazingly, instead of someone inventing a tool for this purpose, children were employed as human chimney sweeps. Their small stature allowed them to go inside the chimneys and manually sweep away the soot. Thus practice went on for over 200 years, in spite of the deplorable conditions the children lived in, the horrible health effects they suffered, and the many injuries and fatalities resulting from related work hazards.

One former chimney sweep, James Seaward was interviewed in December 1909, by the Toronto Saturday Night, a Canadian publication. Seaward was living in Wokingham, where he had just been named alderman of the town’s Borough Council. Seaward was one of the fortunate few that were still alive after working as a chimney sweep for 58 years. He started when he was just six. Seaward tells how he “was only six years old when I went up my first chimney. I was an orphan and I fell into the hands of a chimney sweep, and a cruel master he was. I have known what it was to have straw lighted under me and pins stuck into the soles of my feet to force me up a chimney; and I have known, too, what it was to come down covered with blood and soot after climbing with my knees and elbows. No one knows the terrible cruelty inflicted on boys in those days.

They used to be steeped in strong brine to harden their flesh. In my own case soda was used. Sometimes I used to have to stay up a difficult chimney five or six hours at a stretch.”

They used to be steeped in strong brine to harden their flesh. In my own case soda was used. Sometimes I used to have to stay up a difficult chimney five or six hours at a stretch.”

Somehow, Seaward managed to survive, and to actually prosper, even is such deplorable conditions. Thankfully, such cruelty was outlawed during the nineteenth century, with laws introduced regarding child labor. Those laws didn’t address chimney sweeps specifically, but rather child labor in general. The things that were allowed in the past concerning child labor were just awful, and orphans were specifically targeted, because they had little protections over their lives. They were often “adopted” out, but their “new parents” sometimes just wanted slave labor.