Politics

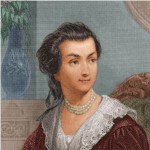

Every politician has his trusted advisors. Often these are high ranking officials who have proven their vast political knowledge and proven that they can be trusted to keep their part of government participation on the straight and narrow for their president. However, not every advisor is a politician or someone in business, or even someone who works at all. Some seek the advice of their wives, but few to the degree of Congressman John Adams, who would later be our second president. John Adams and his wife, Abigail had an interesting political relationship. She was truly his closest confidant. When he needed advice, she was his “go-to girl” in every case. Often, Abigail would be at home maintaining the family farm in Braintree, Massachusetts while her husband was serving on the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. On March 7, 1777, Continental Congressman John Adams wrote three letters to and received two letters from his wife, Abigail.

Every politician has his trusted advisors. Often these are high ranking officials who have proven their vast political knowledge and proven that they can be trusted to keep their part of government participation on the straight and narrow for their president. However, not every advisor is a politician or someone in business, or even someone who works at all. Some seek the advice of their wives, but few to the degree of Congressman John Adams, who would later be our second president. John Adams and his wife, Abigail had an interesting political relationship. She was truly his closest confidant. When he needed advice, she was his “go-to girl” in every case. Often, Abigail would be at home maintaining the family farm in Braintree, Massachusetts while her husband was serving on the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. On March 7, 1777, Continental Congressman John Adams wrote three letters to and received two letters from his wife, Abigail.

The Adams’ correspondence was truly remarkable. Their total letters during his political career numbered 1,160 letters in total, and they covered topics ranging from politics and military strategy to household economy and  family health. For many of the years of Adams’ political career their lives were literally lived in letters. Their mutual respect and adoration showed that even in an age when women were unable to vote, there were nonetheless marriages in which wives and husbands were true intellectual and emotional equals, and the marriage between John and Abigail Adams was one of those.

family health. For many of the years of Adams’ political career their lives were literally lived in letters. Their mutual respect and adoration showed that even in an age when women were unable to vote, there were nonetheless marriages in which wives and husbands were true intellectual and emotional equals, and the marriage between John and Abigail Adams was one of those.

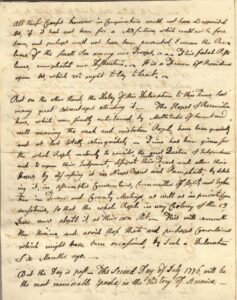

Normally, Congress met in Philadelphia, but in mid-December 1776 Congress decided to move to Baltimore to escape capture by the advancing British. The time in Baltimore was frustrating for the Congress. There were complaints that “the town was exceedingly expensive, and exceedingly dirty, that at times members could make their way to the assembly hall only on horseback, through deep mud.” Throughout the session there was inadequate representation from the various colonies. In those days congressmen came to meetings if they felt they could make it, but excuses for not going were often made too. Even with the shortage of representatives, Samuel Adams declared in the earlier part of the session, “We have done more important business in three weeks than we had done, and I believe should have done, at Philadelphia, in six months.” The congressmen also managed to appoint a committee of five to obtain foreign assistance.

On March 7th, 1777, John drafted his second letter to Abigail. In it he declared that Philadelphia had lost its vibrancy during Congress’ removal to Baltimore. “This City is a dull Place, in Comparason [sic] of what it was. More than one half the Inhabitants have removed to the Country, as it was their Wisdom to do—the Remainder are chiefly Quakers as dull as Beetles. From these neither good is to be expected nor Evil to be apprehended. They are a kind of neutral Tribe, or the Race of the insipids.” While the Adams’ couple did what they had to do to serve their country, I’m sure the years of service were hard on the couple, but never on their marriage. Their love was genuine and forever. Their letters may have been mostly formal and businesslike, but I think that if you read between the lines their letter told so much more about the couple they were.

On March 7th, 1777, John drafted his second letter to Abigail. In it he declared that Philadelphia had lost its vibrancy during Congress’ removal to Baltimore. “This City is a dull Place, in Comparason [sic] of what it was. More than one half the Inhabitants have removed to the Country, as it was their Wisdom to do—the Remainder are chiefly Quakers as dull as Beetles. From these neither good is to be expected nor Evil to be apprehended. They are a kind of neutral Tribe, or the Race of the insipids.” While the Adams’ couple did what they had to do to serve their country, I’m sure the years of service were hard on the couple, but never on their marriage. Their love was genuine and forever. Their letters may have been mostly formal and businesslike, but I think that if you read between the lines their letter told so much more about the couple they were.

When a president leaves office these days, they leave with a lifetime pension, but until 1958, when a president left office, he was not afforded any compensation. That meant that after their time in office, they had to go back to earning a living on their own again. I understand that our presidents have a really big job, but the longest they can be in that office is eight years, so a lifelong pension doesn’t totally make sense to me, but that is clearly another story.

When a president leaves office these days, they leave with a lifetime pension, but until 1958, when a president left office, he was not afforded any compensation. That meant that after their time in office, they had to go back to earning a living on their own again. I understand that our presidents have a really big job, but the longest they can be in that office is eight years, so a lifelong pension doesn’t totally make sense to me, but that is clearly another story.

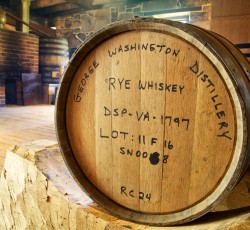

After his term in office, our very first president, George Washington, was approached by James Anderson in 1797, who urged him to open a whiskey distillery. Anderson, who had experience distilling grain in Scotland and Virginia, told Washington that Mount Vernon’s crops, combined with the large merchant gristmill and the abundant water supply, would make a whiskey distillery a very profitable venture, So, after his term, Washington opened that whiskey distillery. By 1799, his distillery was the largest in the country, producing 11,000 gallons of un-aged whiskey!

By the 1810 census, distilleries were quite commonplace in the United States. In fact, there were more than 3,600 operating in Virginia alone, but George Washington’s distillery was one of the largest in the nation at that time, measuring 75 x 30 feet, or 2,250 square feet as opposed to the average being 800 square feet.

George Washington’s whiskey was not bottled, branded, or barrel-aged like most whiskeys of that time. Instead, his was put in an uncharred barrel, which was usually 30 gallons in size. It was then sent into Alexandria, where it was consumed right away as an unaged whiskey. This process brought a hefty stream of cash to Mount Vernon. Not only did George Washington earn his own living, but he also paid taxes on his income. He left office and became a normal everyday citizen again.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon still produces limited batches of both aged and unaged whiskey today. These days, however, the whiskey is placed in branded bottles. It is, nevertheless, produced in the traditional

18th-century way as it was before, in George Washington’s reconstructed distillery, proving yet again that if a president was resourceful, he is unlikely to need a lifelong pension for eight years of work. I have a lot of respect for such a resourceful man like George Washington was. He didn’t expect the American people to carry his lifestyle on their backs for the rest of his life.

18th-century way as it was before, in George Washington’s reconstructed distillery, proving yet again that if a president was resourceful, he is unlikely to need a lifelong pension for eight years of work. I have a lot of respect for such a resourceful man like George Washington was. He didn’t expect the American people to carry his lifestyle on their backs for the rest of his life.

In 1873, the US Congress decided to follow the lead of many European nations and stop buying silver and minting silver coins. Silver was becoming relatively scarce, and it was thought that this new plan would simplify the monetary system. Several other factors exacerbated the situation, and a financial panic quickly set in. Silver prices began dropping rapidly when the government stopped buying silver, and many owners of primarily western silver mines were immediately hurt. The owners of silver weren’t the only ones effected. Farmers and others who carried substantial debt loads attacked the so-called “Crime of ’73.” Theirs might not have been an exact reason, but they believed that it caused a tighter supply of money, which in turn made it more difficult for them to pay off their debts.

In 1873, the US Congress decided to follow the lead of many European nations and stop buying silver and minting silver coins. Silver was becoming relatively scarce, and it was thought that this new plan would simplify the monetary system. Several other factors exacerbated the situation, and a financial panic quickly set in. Silver prices began dropping rapidly when the government stopped buying silver, and many owners of primarily western silver mines were immediately hurt. The owners of silver weren’t the only ones effected. Farmers and others who carried substantial debt loads attacked the so-called “Crime of ’73.” Theirs might not have been an exact reason, but they believed that it caused a tighter supply of money, which in turn made it more difficult for them to pay off their debts.

Most Americans today wouldn’t really understand the problems surrounding the elimination of the coinage of silver. Nevertheless, in the late 19th century, it was a topic of keen political and economic interest. Our money, these days is basically “secured” by faith in the stability of the government, but prior to that time, money was backed by actual  deposits of silver and gold, the so-called “bimetallic standard.” The US also minted both gold and silver coins. The fact that we went away from the “bimetallic standard” or for that matter, the “gold standard” has been a detriment to this country since that time. When money can be made without any gold or silver backing, it weakens the money.

deposits of silver and gold, the so-called “bimetallic standard.” The US also minted both gold and silver coins. The fact that we went away from the “bimetallic standard” or for that matter, the “gold standard” has been a detriment to this country since that time. When money can be made without any gold or silver backing, it weakens the money.

Enter the Bland-Allison Act, which provided for a return to the minting of silver coins. A nationwide drive to return to the “bimetallic standard” began sweeping the nation, and many Americans began to place their undying faith in the ability of silver to solve their economic difficulties. Missouri Congressman Richard Bland led the fight to remonetize silver. Bland was no stranger to the struggles of the small farmers, but his background was in mining. Bland became a fervent believer in the silver cause. William B Allison was a US representative  from 1863 to 1871 and senator from 1873 to 1908 from Iowa. He was also the cosponsor of the Bland-Allison Act of 1878. Both men were against the “faith in the stability of the government” form of currency.

from 1863 to 1871 and senator from 1873 to 1908 from Iowa. He was also the cosponsor of the Bland-Allison Act of 1878. Both men were against the “faith in the stability of the government” form of currency.

The best part of Bland’s part in this was that he had the backing of powerful western mining interests. He quickly secured passage of the Bland-Allison Act, which became law on February 28, 1878. Although the act did not provide for a return to the old policy of unlimited silver coinage, it did require the US Treasury to resume purchasing silver and minting silver dollars as legal tender. Americans could once again use silver coins as legal tender, and this helped some struggling western mining operations. Other than that, however, the act had little economic impact, and it failed to satisfy the greater desires and dreams of the silver backers. The battle over the use of silver and gold continued to occupy Americans well into the 20th century.

Douglas Arnold Preston was destined for great things in the state of Wyoming. Born on December 19, 1858, to Finney D Preston and Phoebe Mundy. He was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1878 and practiced law in Illinois courts until 1887. Then he decided to relocate to Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory. During his life in Wyoming, Preston was not only an attorney, but also a politician. He served as the 6th Attorney General of Wyoming from 1911 to 1919, as a member of the Democratic Party. He also served as a member of the Wyoming House of Representatives from 1903 to 1905, and as a member of the Wyoming Senate in 1929 until his death.

Douglas Arnold Preston was destined for great things in the state of Wyoming. Born on December 19, 1858, to Finney D Preston and Phoebe Mundy. He was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1878 and practiced law in Illinois courts until 1887. Then he decided to relocate to Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory. During his life in Wyoming, Preston was not only an attorney, but also a politician. He served as the 6th Attorney General of Wyoming from 1911 to 1919, as a member of the Democratic Party. He also served as a member of the Wyoming House of Representatives from 1903 to 1905, and as a member of the Wyoming Senate in 1929 until his death.

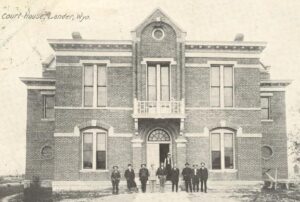

When Preston moved to Wyoming in 1887, he established a law office in Rawlins in partnership with John R Dixon. Apparently, Rawlins wasn’t his cup of tea, so the following year, he moved to Lander, where he continued his legal practice. In 1895, he again relocated, settling in Rock Springs, which became his long-term residence and base for his legal and political career.

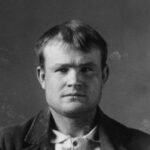

While Preston’s political career was extensive, probably one of the oddest parts of his legal career was the fact that he was once retained as a defense attorney for the infamous Butch Cassidy. Cassidy and his cohort, Al Hainer, had been arrested on April 11, 1892, a seven-man posse led by Uinta County Sheriff John Ward and Deputy Sheriff Bob Calverly, and charged in Fremont County with grand larceny “involving the theft of a horse valued at forty dollars from the Grey Bull Cattle Company on or about October 1, 1891.” District Court Judge Jesse Knight set bond at $400 each and both men were released pending trial. The trial was delayed for more than a year, due mostly to problems encountered in locating one prosecution witness and several defense witnesses. During that time, Cassidy retained Douglas A Preston of Lander as his attorney. Preston was assisted by C F Rathbone.

Preston and Cassidy had crossed paths and become friends so retaining him made sense. Unsubstantiated  rumor has it that Cassidy and Preston met when Cassidy saved Preston from a beating in a saloon in Rock Springs. However, that rumor has been disputed, and since Cassidy was an outlaw, it seems odd that he would play the hero in that one situation. Nevertheless, the two men were friends, and Preston did defend Cassidy.

rumor has it that Cassidy and Preston met when Cassidy saved Preston from a beating in a saloon in Rock Springs. However, that rumor has been disputed, and since Cassidy was an outlaw, it seems odd that he would play the hero in that one situation. Nevertheless, the two men were friends, and Preston did defend Cassidy.

The trial finally began in Lander on June 20, 1893, with Judge Knight presiding. The trial was short and the defense simple. Cassidy and Hainer did not deny being in possession of the horses but maintained they had bought them from a man named Billy Nutcher in good faith, unaware they were stolen. Conveniently, though he had been subpoenaed to testify, Nutcher did not appear at the trial. Nor did two men Cassidy claimed had witnessed the transaction. In the end, the jury deliberated only a few hours before finding both men not guilty. The reality was that there was just not enough evidence.

As the trial progressed and a “not guilty” verdict appeared likely, rancher Otto Franc filed charges against Cassidy and Haines in the theft of different horses in August of 1891, valued at $50. Both were re-arrested and were once again freed on bond. The trial on the new charge opened on June 30, 1894. While Cassidy was found guilty, Hainer was once again acquitted. On July 10, Judge Knight sentenced Cassidy to two years at hard labor in the Wyoming State Penitentiary in Laramie. That pretty much ended the relationship with Preston and Cassidy, and Preston went on to focus on his political career.

Preston served as the prosecuting attorney for Richland County, Illinois from 1880 to 1894. By 1889, and now in Wyoming since 1887, Preston was selected as one of the Democratic delegates to the Wyoming Constitutional Convention. Their task was to draft the state’s constitution for submission to the US government  for statehood. From 1903 to 1905, Preston served in the Wyoming House of Representatives. Governor Joseph M Carey appointed him as Attorney General of Wyoming in 1911, and he was reappointed by Governor John B Kendrick in 1915.

for statehood. From 1903 to 1905, Preston served in the Wyoming House of Representatives. Governor Joseph M Carey appointed him as Attorney General of Wyoming in 1911, and he was reappointed by Governor John B Kendrick in 1915.

Preston was elected to the Wyoming Senate in 1928, but on October 8, 1929, he was involved in a car crash that left him with four broken ribs and a severe skull fracture. Unable to recover from his injuries, Preston died on October 21, 1929, in a hospital in Rock Springs, Wyoming. He was 70 years old. In the 1930 Wyoming state elections, his widow, Anna Preston, was nominated as the Democratic candidate for Wyoming Superintendent of Public Instruction.

As Americans, we are all used to the many scandals that can happen with government corruption or just corruption in general. Most of us have heard of Watergate or Whitewater, which are two of the modern-day scandals of our time. Scandals are pretty common really, mostly because greed will always be something we deal with. I just never really considered the scandal that happened in my own back yard…so to speak. I grew up in Casper, Wyoming, and the scandal involved a president, a senator, two oil men, bribery, and a rock (or rather a dome naked after a rock formation) located north of Casper. The rock formation is known as Teapot Rock, and the scandal involved the oil located within that dome…named Teapot Dome.

As Americans, we are all used to the many scandals that can happen with government corruption or just corruption in general. Most of us have heard of Watergate or Whitewater, which are two of the modern-day scandals of our time. Scandals are pretty common really, mostly because greed will always be something we deal with. I just never really considered the scandal that happened in my own back yard…so to speak. I grew up in Casper, Wyoming, and the scandal involved a president, a senator, two oil men, bribery, and a rock (or rather a dome naked after a rock formation) located north of Casper. The rock formation is known as Teapot Rock, and the scandal involved the oil located within that dome…named Teapot Dome.

The Teapot Dome scandal took place in the 1920s, and it involved national security, big oil companies, bribery, and corruption at the highest levels of the government of the United States. Before Watergate, the Teapot Dome scandal was the most serious scandal in the country’s history. It was named for an that rock formation north of Casper, Wyoming, that looked just like a teapot, but they didn’t care about the rock. It was all about money.

The interest in Teapot Dome began decades before the 1920s scandal. The United States government and US Navy officials, while contemplating a new, global presence, began to realize that they needed a fuel supply that was more reliable and more portable than coal. Requiring the battle ships to make stops to reload their coal supply was not feasible. They needed something that worked better, lasted longer, and took up less space. In order to accommodate the need for coal, the Department of the Navy officials, during the Theodore Roosevelt presidency early in the 20th century, resorted to building coal-fueling stations around the world. That would be a huge undertaking.

The United States began to see that they were severely hampered, as other nations began development of petroleum-powered ships. Developing petroleum-powered ships seems like the logical next step, so beginning in 1909, during the Taft administration, Navy administrators decided that they needed to convert the fleet to the more efficient petroleum. Ships would have no need for coaling stations. Once fueled, the petroleum-powered ships had far greater range. Oddly, considering the scandal, the USS Wyoming, which was a battleship initially launched in 1900, became the first ship in the fleet to be converted to oil power in 1909. The ship was later renamed the USS Cheyenne, because the new battleship USS Wyoming was launched in 1910. Soon, more

ships were converted from coal. With the conversions came the concern about the long-term availability of oil. They didn’t understand at that time, the longevity of oil. They worried about what would happen if oil were to run out? The Navy would be paralyzed!!

ships were converted from coal. With the conversions came the concern about the long-term availability of oil. They didn’t understand at that time, the longevity of oil. They worried about what would happen if oil were to run out? The Navy would be paralyzed!!

As a result of these concerns, Navy administrators asked Congress to set aside federally owned lands in places where known oil deposits most likely existed. The plan was to reserve these “naval petroleum reserves” for any future event that could have resulted from a national emergency. One of the three petroleum reserves set aside was near Salt Creek in northern Natrona County, you guessed it…Teapot Dome. “A dome is a geological formation that traps oil underground between impervious layers of rock, with the upper layer bent upward to form a dome.” Reserving those areas, was like screaming “come and get me” to oilmen. They all wanted the opportunity to drill within these federally owned reserves.

Enter President Warren G Harding, who was elected president in 1920. Harding’s friend, and poker buddy, US Senator Albert Fall, was picked to be Harding’s secretary of Interior. Fall was a rancher and New Mexico’s first US senator. He immediately accepted the cabinet post. It was the beginning of the scandal, because Fall had “ideas” that would be “helpful” to both of them. Within a few weeks, Fall worked quickly to convince President Harding to allow transfer of the naval petroleum reserves from the Navy to the Department of the Interior. His argument was that the department was “better able” to oversee the protection of these areas where oil was not to be produced but kept in case of emergency. That basically put Fall in charge of the oil reserves, to do with as he saw fit.

Fall made secret deals with two prominent oilmen, Edward Doheny and Harry Sinclair. Both men were close friends of Fall. Of course, Fall didn’t just give them access to the reserves. They paid him bribes to authorize them to drill in the three naval petroleum reserves. The law was specific, saying that access was not to be granted unless it was an emergency situation, and no such emergency existed.

Wyoming Governor Leslie Miller, himself an independent oilman became suspicious when he saw trucks with the Sinclair company logo hauling drilling equipment into the Teapot Dome naval petroleum reserve. He asked US Senator John B Kendrick to look into the matter. Kendrick, sensing wrongdoing, turned the question over to a special Senate investigating committee. At about that time, President Harding took a summer trip west, stopping in Wyoming, enjoying Yellowstone and continuing on to Alaska and, eventually, to San Francisco. While in San Francisco, the President died suddenly. While no one would want to say his death was a good thing, but it’s quite likely that Harding escaped impeachment for his role in Teapot Dome. Of course, there wasn’t exactly proof that he knew anything about the situation, not evidence that he took bribes. Still, there is no proof he didn’t either.

Fall was convicted and sent to federal prison, the first Cabinet-level officer in American history to go to jail for

crimes committed while serving in office. Both Sinclair and Doheny were exonerated of the main charge…giving bribes to Fall. As a newspaper reporter observed when the two wealthy oilmen were found not guilty, “You can’t convict a million dollars.” Sinclair was sentenced to a 9-month prison term not for bribery but for contempt of Congress, and for charges connected to his hiring of detectives to trail members of the jury in the original bribery trial

crimes committed while serving in office. Both Sinclair and Doheny were exonerated of the main charge…giving bribes to Fall. As a newspaper reporter observed when the two wealthy oilmen were found not guilty, “You can’t convict a million dollars.” Sinclair was sentenced to a 9-month prison term not for bribery but for contempt of Congress, and for charges connected to his hiring of detectives to trail members of the jury in the original bribery trial

In federal court in Wyoming the federal government filed a lawsuit to cancel the illegally obtained leases of Teapot Dome oil reserves. US District Judge T Blake Kennedy ruled against the government, but the US Supreme Court overturned the Kennedy decision, and the leases were canceled.

It is a tradition in the United States, that every four years on January 20, there is a transition of power. The incoming president is sworn in and afterward, the outgoing president leaves the White House…or sometimes the outgoing president leaves before the swearing in of the new president. Unfortunately, not every transition is an amiable one or even a peaceful one. I suppose that is because neither side likes to lose. In fact, when the opposing party takes over the White House these days, it usually isn’t a peaceful transition. Often there are protesters and sometimes things get out of hand…and of course, there is plenty of blame to go around. The truth is often very obscured, and the blame is laid on the wrong party. You can like what I say, or not, but the reality is that there is plenty of proof concerning the January 6th event of 2021, and the wrong people were accused.

It is a tradition in the United States, that every four years on January 20, there is a transition of power. The incoming president is sworn in and afterward, the outgoing president leaves the White House…or sometimes the outgoing president leaves before the swearing in of the new president. Unfortunately, not every transition is an amiable one or even a peaceful one. I suppose that is because neither side likes to lose. In fact, when the opposing party takes over the White House these days, it usually isn’t a peaceful transition. Often there are protesters and sometimes things get out of hand…and of course, there is plenty of blame to go around. The truth is often very obscured, and the blame is laid on the wrong party. You can like what I say, or not, but the reality is that there is plenty of proof concerning the January 6th event of 2021, and the wrong people were accused.

We all have our own opinion on the 2020 election, and I won’t dispute that or its outcome, but now the people of this nation have spoken…again, in a truly fair election, and we are about to put President Donald J Trump back in the White House. The transition actually began when he won the United States presidential election on November 5, 2024, becoming the president-elect. Because of our system, his formal election came when the Electoral College voted on December 17, 2024. The results were certified by a joint of Congress on January 6, 2025, and the transition is scheduled to conclude with Trump’s inauguration on January 20, 2025.

I think this country is so ready for the changes President Trump will bring back. His first term in office showed  the people just how prosperous the country could be. We were almost energy independent; gas prices were low, patriotism was high, and things made sense. All that went away when Biden took office. It was as if the whole country went crazy. Now that President Trump is coming back, things are turning around so quickly that it is awe inspiring. The whole feel of things in this country is taking a 180° turn…overnight. It is amazing. The people he has chosen for his cabinet totally add to the air of excitement. And of course, we are very excited with his vice-presidential choice. Vice President JD Vance came up from poor roots, but worked hard to make something of himself, and I think he will be an amazing vice president. This president will bring back common sense.

the people just how prosperous the country could be. We were almost energy independent; gas prices were low, patriotism was high, and things made sense. All that went away when Biden took office. It was as if the whole country went crazy. Now that President Trump is coming back, things are turning around so quickly that it is awe inspiring. The whole feel of things in this country is taking a 180° turn…overnight. It is amazing. The people he has chosen for his cabinet totally add to the air of excitement. And of course, we are very excited with his vice-presidential choice. Vice President JD Vance came up from poor roots, but worked hard to make something of himself, and I think he will be an amazing vice president. This president will bring back common sense.

Trump became the presumptive nominee of his party on March 12, 2024, and formally accepted the nomination at the Republican National Convention in July. On August 16th, Trump announced the formation of the transition team with Linda McMahon, Trump’s former head of the Small Business Administration, and Howard Lutnick, the billionaire CEO of Cantor Fitzgerald and BGC Group, officially named as co-chairs. Vice presidential nominee JD Vance, along with sons Donald Jr. and Eric Trump, were designated as honorary co-chairs. The effort beginning at this time was considered unusually late, as historically, most transition efforts start in late spring. Nevertheless, this team is very capable, and they will have everything in readiness. Attorney Robert F Kennedy Jr and former congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard were added as honorary co-chairs on August 27th. Both are former Democrats who had recently endorsed Trump. Kennedy had initially launched an independent presidential campaign before withdrawing to endorse Trump. Kennedy is reportedly in for a Cabinet position in this administration.

Watching the inauguration today felt like the opening of prison doors. The nation has been under such oppression, and negativity. The future seemed hopeless, but all that changed at 12:01pm in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington DC. President Trump outlined the things he plans to do, and with each on, we began to

feel hope again. He is so sharp, and when he sees something that is wrong, he goes after it. He works to correct the problem and repair the situation. President Trump is a very hands-on, go get ’em kind of guy, and he is not politically correct, an action that has had a crippling effect on this nation. With President Trump’s return to the White House comes dignity, hope, patriotism, transparency, honesty, and truthfulness. I say bring it on President Trump. We are ready for you!!

feel hope again. He is so sharp, and when he sees something that is wrong, he goes after it. He works to correct the problem and repair the situation. President Trump is a very hands-on, go get ’em kind of guy, and he is not politically correct, an action that has had a crippling effect on this nation. With President Trump’s return to the White House comes dignity, hope, patriotism, transparency, honesty, and truthfulness. I say bring it on President Trump. We are ready for you!!

In 1800, President John Adams approved legislation that appropriated $5,000 to purchase “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” The initial collection of books, ordered from London, arrived in 1801. These were stored in the US Capitol. The books were the library’s first. The inaugural library catalog, dated April 1802, listed 964 volumes and nine maps. The library was President Adams’ pride and joy. In 1814, in what was a largely symbolic maneuver, the British entered Washington DC and burned down the capitol and the library. The fire was dramatic, but really had little relevance, because the city didn’t have an especially large population and, since much of the US government had fled before the British could overtake them, there was little strategic value in the destruction. Nevertheless, the about 3,000 books were lost in that fire.

In 1800, President John Adams approved legislation that appropriated $5,000 to purchase “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” The initial collection of books, ordered from London, arrived in 1801. These were stored in the US Capitol. The books were the library’s first. The inaugural library catalog, dated April 1802, listed 964 volumes and nine maps. The library was President Adams’ pride and joy. In 1814, in what was a largely symbolic maneuver, the British entered Washington DC and burned down the capitol and the library. The fire was dramatic, but really had little relevance, because the city didn’t have an especially large population and, since much of the US government had fled before the British could overtake them, there was little strategic value in the destruction. Nevertheless, the about 3,000 books were lost in that fire.

The Library of Congress must seem like an institution that is unable to be defeated, but the reality is that while it has been there practically forever, acting as the nation’s biggest library, it has been almost destroyed three times. The Library of Congress is one of the largest libraries in the world, with over 170 million items in its collections at present, according to the Library of Congress itself. It possesses a world class collection of rare books and holds the largest known collection of audio recordings, maps, and films, among other materials. It is accessible not only to the Congressional representatives who work nearby in the Capitol, but also to all Americans and members of the public. That was not always the case, however. At its inception, the Library of Congress was for congressional use only.

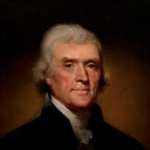

Once the fires of the British died down, they left Washington, and the American lawmakers returned. As has always been the way of Americans, they knew it was time to rebuild. While Congress was putting itself back together, it became clear that most wanted the Library of Congress to return as well. At that point, former president Thomas Jefferson stepped in. He offered to sell his own library to reconstitute the one lost in 1814. It is certainly logical that Jefferson was one proposing such a deal. According to the Library of Congress, he was an avid book reader and lifelong learner with an extensive personal library. While he committed to the notion of an informed, intellectual Congress, Jefferson may have also empathized on a deeper level. In 1770, his own home had burned, and Jefferson, gazing at the ashes, most acutely felt the loss of his books. Later, he would come to possess the largest private library in the United States.

The Library of Congress faced at least three fires in its fight to exist. In fact, its existence as an institution has been challenged numerous obstacles throughout its more than 200 years of existence. The Library of Congress faced space shortages, understaffing, and lack of funding, until the American Civil War increased the importance of legislative research to meet the demands of a growing federal government. Then, in 1870, the library gained the right to receive two copies of every copyrightable work printed in the United States. It also built its collections through acquisitions and donations. Between 1890 and 1897, a new library building, which has now

been renamed the Thomas Jefferson Building, was constructed. Two additional buildings, the John Adams Building (opened in 1939) and the James Madison Memorial Building (opened in 1980), were later added. In total, the Library of Congress has faced major fires at least three times in its history.

been renamed the Thomas Jefferson Building, was constructed. Two additional buildings, the John Adams Building (opened in 1939) and the James Madison Memorial Building (opened in 1980), were later added. In total, the Library of Congress has faced major fires at least three times in its history.

According to the United States House of Representatives, the 1825 fire occurred on the evening of December 22nd. Massachusetts Representative Edward Everett, who was leaving a nearby party, noticed a strange light coming from the library windows. When he informed a Capitol police officer, who did not have a key, Everett dismissed the situation. However, as the glow intensified, it became increasingly difficult to ignore. Eventually, more officers, along with Librarian of Congress George Watterson, discovered the dreadful truth: Library of Congress was on fire…again!!

Both representatives and firefighters fought the blaze, including’s fellow Massachusetts representative, Daniel Webster, and Tennessee politician Sam Houston. They extinguished fire before it spread to the rest of the Capitol. Ultimately, it was determined that the cause was a candle left lit in the room. The damage was not nearly as extensive as the 1814, though some books and a rug were lost.

On December 24, 1851, what is thought to be the most devastating fire destroyed 35,000 books, two-thirds of the library’s collection, and two-thirds of Jefferson’s original transfer. In 1852, Congress appropriated $168,700 to replace the books but not to acquire new materials. By 2008, the librarians of Congress had found replacements for all but 300 of the works documented as being in Jefferson’s original collection. This marked the beginning of a conservative period in the library’s administration under librarian John Silva Meehan and joint committee chairman James A. Pearce, who restricted the library’s activities. Meehan and Pearce’s views on limiting the Library of Congress’s scope were shared by members of Congress. As a librarian, Meehan and perpetuated the notion that “the congressional library should play a limited role on the national scene and its collections, by and large, should emphasize American materials obvious use to the US Congress.” In 1859, Congress transferred the library’s public document distribution activities to the Department of the Interior and its international book exchange program to the Department of State.

These days, the library is open for academic research to anyone with a Reader Identification Card. The library items may not be removed from the reading rooms or the library buildings. Most of the library’s general collection of books and journals are in the closed stacks of Jefferson and Adams Buildings. Specialized collections of books and other materials are in stacks in three main library buildings or stored off-site. Access to the closed stacks not permitted under any circumstances, except to authorized library staff and occasionally to dignitaries. Only reading room reference collections are on open shelves.

Since 1902, American libraries have been able to request books other items through interlibrary loan from the Library of Congress, if these are not available elsewhere. Through this system, the Library of Congress has served as a “library of last resort,” according to former librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam. The Library of Congress lends books to other libraries with the stipulation that they be used only inside the borrowing library. In 2017, the Library of Congress began development of a reader’s card for children under the age of sixteen.

Since 1902, American libraries have been able to request books other items through interlibrary loan from the Library of Congress, if these are not available elsewhere. Through this system, the Library of Congress has served as a “library of last resort,” according to former librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam. The Library of Congress lends books to other libraries with the stipulation that they be used only inside the borrowing library. In 2017, the Library of Congress began development of a reader’s card for children under the age of sixteen.

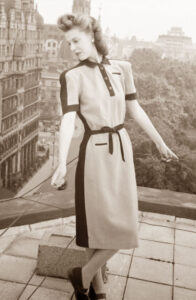

During World War II, as with other wars, things that were needed for the war effort had to be rationed. Things like metal, gasoline, even food made sense to me, but while I was listening to a book called “The Monuments Men” and shorter skirts were mentioned. My first thought was, “How did shorter skirts help the war effort? The men’s morale maybe, but seriously…how?” Well, it turns out that morale had nothing to do with it. The reasons lay elsewhere. Apparently, wool and silk were in high demand to make uniforms and parachutes. For manufacturers, that meant using materials like rayon and viscose (a semi-synthetic type of rayon fabric made from wood pulp that is used as a silk substitute. It has a similar drape and smooth feel to the luxury material) to make most civilians clothing.

During World War II, as with other wars, things that were needed for the war effort had to be rationed. Things like metal, gasoline, even food made sense to me, but while I was listening to a book called “The Monuments Men” and shorter skirts were mentioned. My first thought was, “How did shorter skirts help the war effort? The men’s morale maybe, but seriously…how?” Well, it turns out that morale had nothing to do with it. The reasons lay elsewhere. Apparently, wool and silk were in high demand to make uniforms and parachutes. For manufacturers, that meant using materials like rayon and viscose (a semi-synthetic type of rayon fabric made from wood pulp that is used as a silk substitute. It has a similar drape and smooth feel to the luxury material) to make most civilians clothing.

In addition to the types of material, the manufacturers had to find a way to actually conserve the amount of fabric being used, so to conserve fabric, dressmakers and manufacturers began designing shorter skirts and slimmer silhouettes. In the book, the comment was made that because so many people walked to work, the women had shapely legs, so I guess the men appreciated the new styles, much like when the miniskirt came into style in the 70s. Although, the women of the World War II era didn’t wear miniskirts. The dresses were just about knee length or slightly longer. The use of shoulder pads ended in World War II as well, although it has made periodic comebacks over the years. Another way that the manufacturers found to conserve fabric, was

the elimination of the cuff on men’s slacks. Oddly, that change was not as much appreciated by the men in World War II, although these days, cuffs on pants are a rarity, if you see them at all. Mostly these days, you might see pant legs rolled and that mostly on women, but not a real cuff.

the elimination of the cuff on men’s slacks. Oddly, that change was not as much appreciated by the men in World War II, although these days, cuffs on pants are a rarity, if you see them at all. Mostly these days, you might see pant legs rolled and that mostly on women, but not a real cuff.

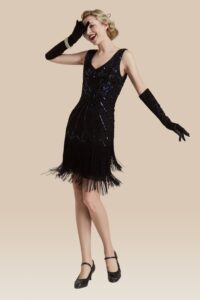

Dress hemlines have been known to fluctuate with the times. The pre 1900s showed women with long full dresses that even dragged the ground, full slips and absolutely no ankles or feet showing. I suppose anyone showing an ankle or foot would be considered…loose. By the 1900s, the era of my Spencer great aunts, the skirts were still very long, but with a slimmer cut and fewer full slips to carry around. One of the oddest style came in 1910, when the Hobble Skirt came out. Of course, variations would be the pencil skirt. The roaring 20s, brought a carefree attitude and long cumbersome skirts were replaced with short, knee length (and maybe slightly shorter) skirts, suitable for rather wild dancing. With the stock market crash of 1929, the Crashing 30’s began, and skirts were again long and very conservative. There was no need for flashy dancewear, and there was not much dancing going on. Then, came World War II. Our men were fighting and we…the ones back at home had to make some sacrifices, So, came the shorter skirts made of rayon and such to save the normal materials for our “boys, fighting over there.” When the war ended, the ration weary women went back to their fuller, and slightly longer skirt, because…well they could. And then came the 60s…the era of free love and free expression. The miniskirt arrived, much to the horror of our parents. The Beatles were the rage, and the skirts grew (or shrank) to ever

shorter lengths. By the late 70s, the midi and maxiskirts had arrived. And so came the Hippie era. Everything was “free flowing and filled with flowers.” To me, it seems that since that time, skirts have been a mix of lengths, from the micromini to the maxi, but in reality, many women gave up skirts completely for jeans, short shorts (hot pants), capris, or whatever else suited our “fancies” because it was all available. I suppose a day could come again, when fashion would change because of war, politics, or personal preference. Styles often repeat. Time will tell that story.

shorter lengths. By the late 70s, the midi and maxiskirts had arrived. And so came the Hippie era. Everything was “free flowing and filled with flowers.” To me, it seems that since that time, skirts have been a mix of lengths, from the micromini to the maxi, but in reality, many women gave up skirts completely for jeans, short shorts (hot pants), capris, or whatever else suited our “fancies” because it was all available. I suppose a day could come again, when fashion would change because of war, politics, or personal preference. Styles often repeat. Time will tell that story.

I’ve been listening to an audiobook called the “The Germans In Normandy.” Of course, I’m not a fan of the Germans in World War II, but this book talks about the German perspective about that battle. We all think that the German soldiers went blindly into battle, faithful to their leader…or at least most of them, but the German soldiers all had doubts. They all thought Hitler was about half crazy, but they were afraid to say anything…for the most part anyway.

I’ve been listening to an audiobook called the “The Germans In Normandy.” Of course, I’m not a fan of the Germans in World War II, but this book talks about the German perspective about that battle. We all think that the German soldiers went blindly into battle, faithful to their leader…or at least most of them, but the German soldiers all had doubts. They all thought Hitler was about half crazy, but they were afraid to say anything…for the most part anyway.

As I’ve listened to the book, the Hitler Youth came into the story, and I began to wonder, not only how the Hitler Youth felt about Hitler and the Third Reich, but how many of them stayed faithful to Hitler’s ideals and how many of them turned from Hitler’s ideals. So, I did a little research.

Hitler believed that by conditioning young people in groups as the Hitler Youth, they “never be free again, not in their whole lives.” While many young individuals were profoundly influenced by these organizations, support for the Hitler Youth was not as extensive as Nazi leaders had hoped. The youth initially joined and were very excited about their participation, but as time went on, their interest declined. Many young people skipped certain meetings and activities, despite mandatory attendance requirements, resulting in inconsistent loyalty. The reasons behind their declining enthusiasm for Hitler Youth activities were not solely political or moral at times, young individuals simply grew weary of the numerous obligations or became bored. In 1939, the Social Democratic Party, which had been banned by the Nazis and operated covertly, published a report on German  youth that highlighted some of this frustration. Young people are notorious for promoting change, and that was what they thought they were doing. The restrictions placed on them by the organizers of the Hitler Youth made many of the youth want to walk away.

youth that highlighted some of this frustration. Young people are notorious for promoting change, and that was what they thought they were doing. The restrictions placed on them by the organizers of the Hitler Youth made many of the youth want to walk away.

Of those who did walk away was Hans Scholl, along with Alexander Schmorell, one of the two founding members of the White Rose resistance movement in Nazi Germany. The White Rose was a non-violent, intellectual resistance group in the Third Reich. The group was led by Hans Scholl, and his sister, Sophie, along with several other former Hitler Youth members. The students attended the University of Munich. Their objective was to raise awareness through anonymous leaflets and a graffiti campaign that called for active opposition to the Nazi regime. the anonymity of their actions, Third Reich had spies everywhere. Hans became disillusioned because he had assembled a collection of folk songs, and his young charges loved to listen to him singing, accompanying himself on his guitar. He knew not only the songs of Hitler Youth but also the folk songs of many peoples and many lands. He loved how magically a Russian or Norwegian song sounded with its dark and dragging melancholy. And he thought about what it told of the soul of those people and their homeland! Then, Hans was told the songs were not allowed. He had aways thought that people should be able to pursue the things that interested them, but now the Hitler Youth program was no longer what he thought it was, and he walked away.

Hans and Sophie Scholl, along with Christoph Probst, were prominent members of the core group. The activities of The White Rose in Munich began on June 27, 1942, and ended in the arrest of the group by the Gestapo on February 18, 1943. Those apprehended now faced death sentences or imprisonment in show trials conducted

by the Nazi People’s Court (Volksgerichtshof). During the trial, Sophie interrupted the judge multiple times, but her remarks went unacknowledged. The defendants were not given the opportunity to speak. They had no means to defend themselves and were declared guilty during the “trial.” They were executed by guillotine four days after their arrest, on February 22, 1943. The group, which had only been active for eight months, had never committed any violent acts. They were sentenced to death. Hitler’s regime regarded them as a greater threat due to their pamphlets and art than if they had killed people.

by the Nazi People’s Court (Volksgerichtshof). During the trial, Sophie interrupted the judge multiple times, but her remarks went unacknowledged. The defendants were not given the opportunity to speak. They had no means to defend themselves and were declared guilty during the “trial.” They were executed by guillotine four days after their arrest, on February 22, 1943. The group, which had only been active for eight months, had never committed any violent acts. They were sentenced to death. Hitler’s regime regarded them as a greater threat due to their pamphlets and art than if they had killed people.

I would think that the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 17, 1989, would have signaled the end of an era of oppressive treatment of people in the area. Nevertheless, just nine days after the fall, and approximately 200 miles south, a large group of students descended into Prague, Czechoslovakia, to protest against the communist regime in their area. This demonstration sparked the onset of the Velvet Revolution, which was the peaceful overthrow of the Czechoslovak government. It was part of a wave of anti-communist revolutions that developed in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

I would think that the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 17, 1989, would have signaled the end of an era of oppressive treatment of people in the area. Nevertheless, just nine days after the fall, and approximately 200 miles south, a large group of students descended into Prague, Czechoslovakia, to protest against the communist regime in their area. This demonstration sparked the onset of the Velvet Revolution, which was the peaceful overthrow of the Czechoslovak government. It was part of a wave of anti-communist revolutions that developed in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

This wasn’t just a random protest. Protesters selected November 17th to coincide with International Students Day, marking the 50th anniversary of a Nazi assault on the University of Prague. That attack had resulted in nine deaths and the imprisonment of 1,200 students in concentration camps. The area was governed by a single communist party aligned with Moscow since World War II’s conclusion, the Czechoslovak government permitted very little anti-government expression and severely repressed opposition. Strangely, the government authorized the march on International Students Day. In recent years, as the Soviet Bloc’s economy faltered and democratic movements toppled communist governments in Poland and Hungary, anti-government sentiment has grown increasingly pronounced.

Students shouting anti-government slogans filled the streets of Bratislava and Prague. There were confrontations with the police, but officially, no fatalities were reported. Despite police crackdowns, the protests overflowed into other cities and increased rapidly. Theater employees transformed their stages into public debate platforms, and the movement swelled to encompass a diverse cross-section of society. On November 20th, half a million demonstrators gathered in Prague’s Wenceslas Square.

Shortly after the initial protests, it became clear that one-party rule in Czechoslovakia was ending. The Communist Party’s leadership stepped down on November 28th, and by December 10th, an anti-communist government had taken office. Václav Havel, a renowned writer and dissident, was elected president on December 29th, serving as Czechoslovakia’s final president. Subsequently, the Czech and Slovak regions amicably parted ways in the so-called Velvet Divorce, and in 1993, Havel became the first president of the newly established Czech Republic.

It was an amazing feat for the students. Somehow, they managed to pull off a peaceful regime change. The oppressive regime they had always known, was replaced with two free nations and peace. Peaceful revolutions

are pretty much unheard of. Dictatorships hate to relinquish their power over their helpless citizens, and typically, the students just don’t have much pull in government, although that may be changing. Nevertheless, in a time when they shouldn’t have been able to pull it off, the students of Prague, Czechoslovakia managed an unbelievable feat.

are pretty much unheard of. Dictatorships hate to relinquish their power over their helpless citizens, and typically, the students just don’t have much pull in government, although that may be changing. Nevertheless, in a time when they shouldn’t have been able to pull it off, the students of Prague, Czechoslovakia managed an unbelievable feat.